Mapping Global Research Trends on Aflatoxin M1 in Dairy Products: An Integrative Review of Prevalence, Toxicology, and Control Approaches

Abstract

1. Introduction

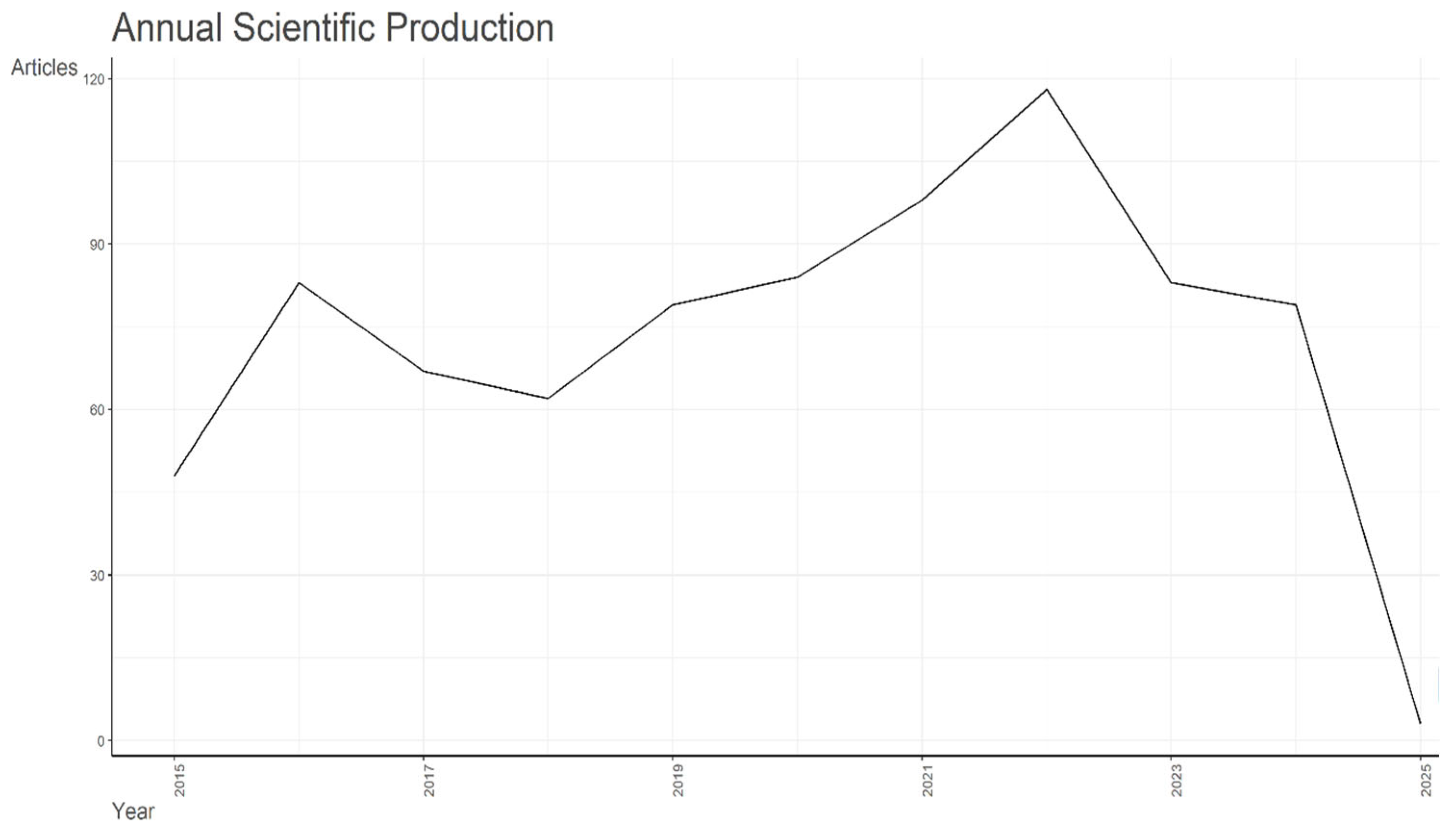

2. Bibliometric and Scientometric Analysis of Aflatoxin M1 Research in Dairy

2.1. Research Strategy

2.2. Bibliography Analysis

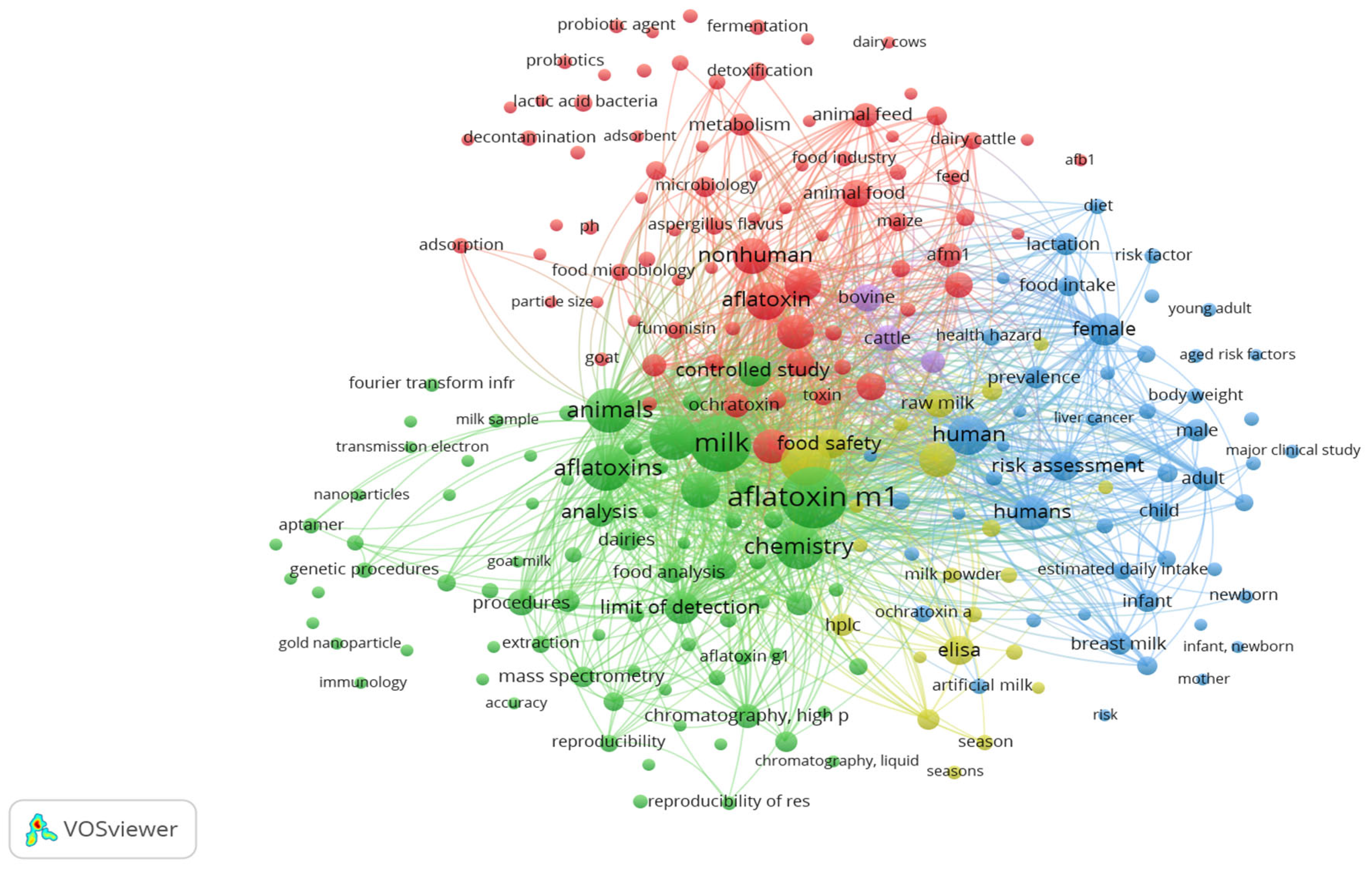

- The purple cluster with keywords such as bovine and cattle focuses on the carry-over of AFB1 from contaminated feed into milk in dairy livestock. This area of study is principal for understanding the biosynthesis of AFM1, which occurs in the liver of lactating animals after the ingestion of contaminated feed and is excreted into the milk. The finding shows the important role of the ruminants in the aflatoxin transmission chain;

- The blue cluster highlights human health and risk assessment, including terms like risk factor, infant, female, liver cancer, breast milk, and estimated daily intake. This cluster focuses on AFM1 exposure, especially in vulnerable populations (infants, newborns, and breast milk), and its potential carcinogenic impact (health hazard, liver cancer);

- The yellow cluster relates to prevalence studies, food safety monitoring, and exposure assessments with keywords such as food safety, season, Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA), and milk powder. These terms indicate the application of analytical methodologies in prevalence studies, seasonal monitoring, and regulatory surveillance to ensure public health protection.

- The green cluster centers around analytical methodologies in detecting AFM1 in dairy products, with terms such as chromatography, High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), mass spectrometry, limit of detection, analysis, extraction, and nanoparticles.

- The red cluster focuses on mitigation strategies targeting aflatoxin contamination in the pre-harvest and feed to food contamination, with terms like lactic acid bacteria, probiotics, fermentation, physicochemical methods, adsorbent, detoxification, and decontamination. These keywords indicate a strong research focus on mitigation, especially environmentally friendly methods, and food-grade interventions to bind, degrade, or eliminate aflatoxins either in animal feed or during dairy product processing. The presence of other terms such as animal feed, goat, and dairy cattle indicates, as well, the focus on limiting AFB1 exposure at the farm level to reduce AFM1 excretion into milk.

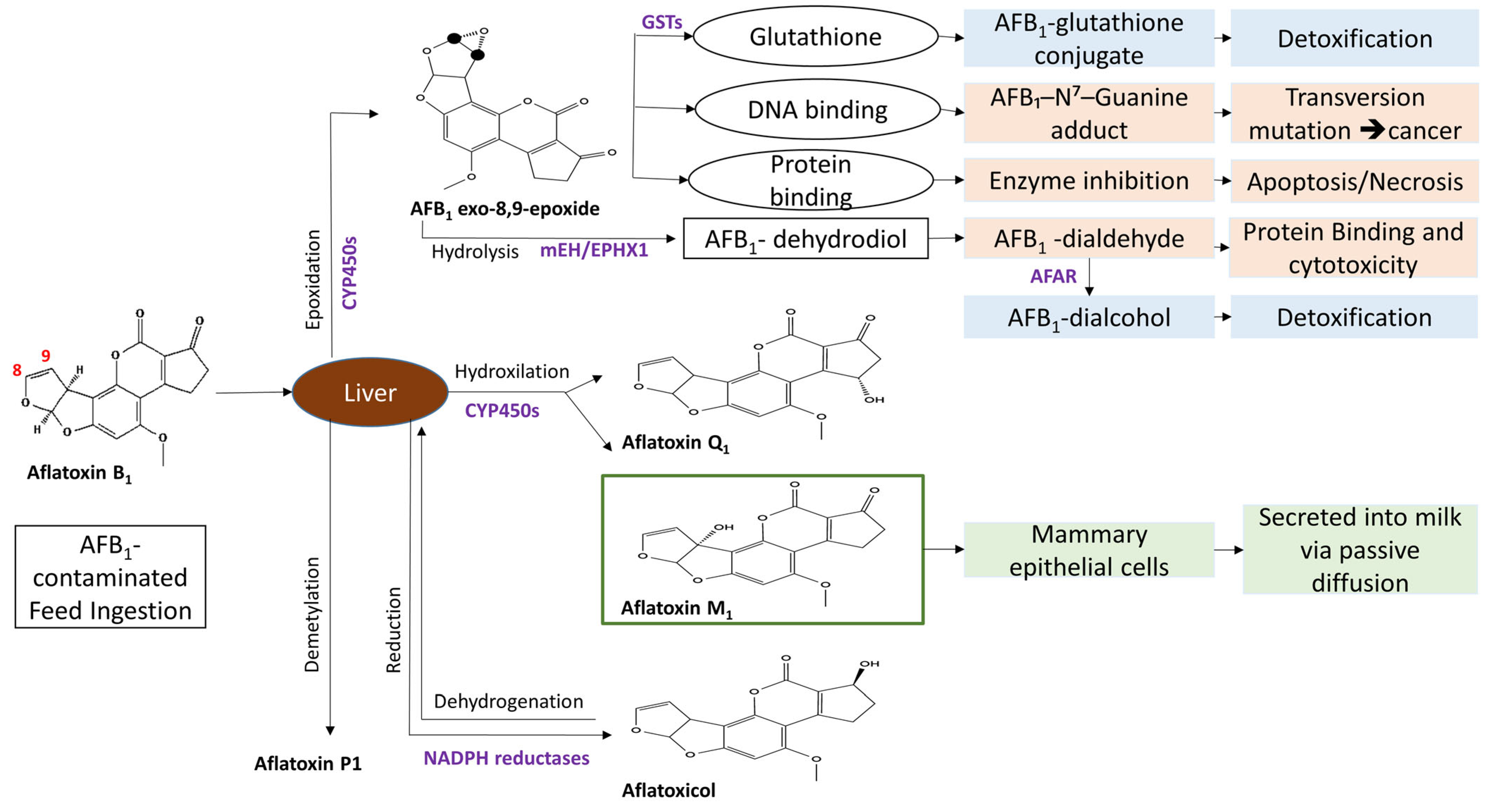

3. Aflatoxin M1 Biosynthesis and Toxicological Impact on Animals

4. Aflatoxin M1 Biosynthesis and Toxicological Impact on Humans

5. International Regulations of Aflatoxin M1

6. Global Prevalence of Aflatoxin M1

7. Mitigation Strategies

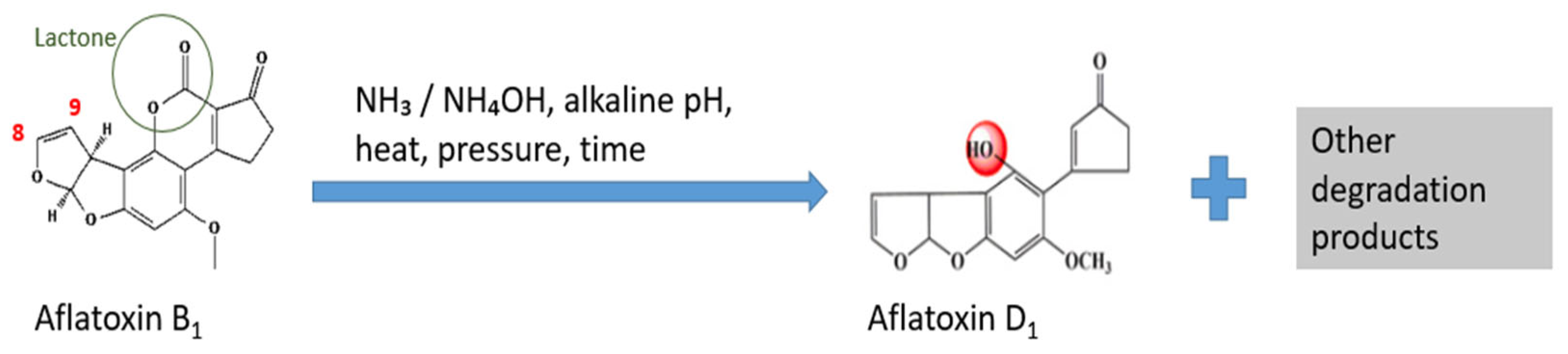

7.1. Chemical Mitigation Techniques

7.1.1. Alkaline Agents

7.1.2. Oxidizing Agents

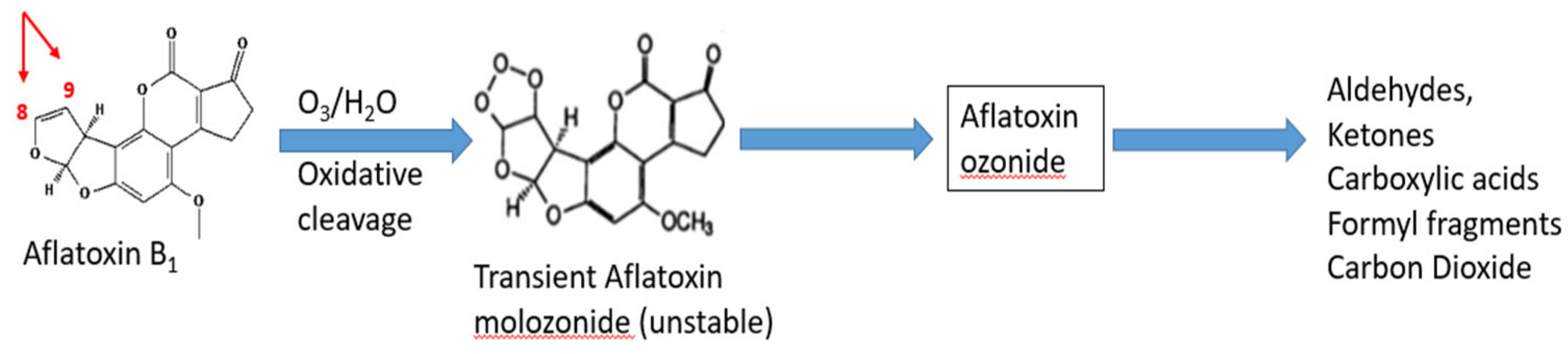

Ozonation

Hydrogen Peroxide

7.1.3. Adsorbents

Bentonite

Other Dietary Adsorbents

7.2. Biological Mitigation Techniques

7.2.1. Microorganisms

Lactic Acid Bacteria

LAB and Yeast Synergies

Bifidobacteria and Cell-Wall Components

Synergistic Strategies

7.2.2. Indirect Mitigation via Feed

7.2.3. Enzymes and Bioactive Compounds

7.2.4. Natural Additives

7.3. Physical Mitigation Techniques

7.3.1. Processing Impact on AFM1

7.3.2. Barrier System and Innovative Material

7.3.3. Irradiation-Based Technique

7.3.4. Thermal and Non-Thermal Approaches

8. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFAR | Aflatoxin aldehyde reductase |

| AFB1 | Aflatoxin B1 |

| AFL | Aflatoxicol |

| AFM1 | Aflatoxin M1 |

| BDL | Below detection limit |

| BDP | Biodegradation product |

| BENT | Bentonite |

| CBENT/CA | C combination with bentonite and activated carbon |

| CFU | Colony forming unit |

| CYP450 | Cytochrome P450 enzymes |

| DOI | digital object identifiers |

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| EPS | Exopolysaccharides |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FLD | Fluorescence detection |

| FUM | Fumonisin |

| GRAS | Generally recognized as safe |

| GSTs | Glutathione S transferases |

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

| HCC | hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HPLC | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| HPP | High-pressure processing |

| HSCAS | hydrated sodium calcium aluminosilicate |

| HVACP | High Voltage Atmospheric Cold Plasma |

| ICSE | Inorganic Composite Sorbent Extractant |

| IARC | International Agency for Research on Cancer |

| IF | Impact factor |

| IGF | Insulin-like growth factor |

| JECFA | The Joint Committee between FAO and WHO Experts on Food Additives |

| RH | Relative humidity |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| LAB | Lactic acid bacteria |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

| LFA | Commercial lateral flow assay |

| LLGI | low-level gamma irradiation |

| LOD | Limit of detection |

| LOQ | Limit of quantification |

| MBNC | Magnetic bentonite nanocomposites |

| MB | Modified bentonite |

| MBNC | Magnetic bentonite nano-composite |

| MC-LR | Microcystin-LR |

| mEH | Microsomal epoxide hydroxylase |

| MENA | Middle East and North Africa |

| ML | Maximum limit |

| MOE | Margin of exposure |

| MOS | Mannan oligosaccharides |

| Mt-CS/CFS NSs | Metformin–chitosan/silica-cobalt ferrite nanospheres |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| NSFC | National Natural Science Foundation of China |

| MX | Multi-toxin binder mixes |

| NB | Natural bentonite |

| ND | Not determined |

| NP | Nanoparticles |

| OTA | Ochratoxin A |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline washes |

| PEF | Pulsed electric fields |

| PG | Peptidoglycan |

| PTCC | Persian-type culture collection |

| RG | Radioactive granite |

| RSM | Reconstituted skim milk |

| rPODs | Recombinant peroxidases |

| SM | Sorbitan monostearate |

| SODs | Superoxide dismutases |

| UHT | Ultra-high temperature |

| UPLC | Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| YCW | Yeast cell wall |

| ZEN | Zearalenone |

References

- Ostry, V.; Malir, F.; Toman, J.; Grosse, Y. Mycotoxins as Human Carcinogens—The IARC Monographs Classification. Mycotoxin Res. 2017, 33, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, F.; Wang, X.; Sang, Y. Superoxide Dismutase, a Novel Aflatoxin Oxidase from Bacillus Pumilus E-1-1-1: Study on the Degradation Mechanism of Aflatoxin M1 and Its Application in Milk and Beer. Food Control 2024, 161, 110372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, F. Global Burden of Aflatoxin-Induced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Risk Assessment. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118, 818–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goessens, T.; Tesfamariam, K.; Njobeh, P.B.; Matumba, L.; Jali-Meleke, N.; Gong, Y.Y.; Herceg, Z.; Ezekiel, C.N.; Saeger, S.D.; Lachat, C.; et al. Incidence and Mortality of Acute Aflatoxicosis: A Systematic Review. Environ. Int. 2025, 199, 109461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milicevic, D.; Nesic, K.; Jaksic, S. Mycotoxin Contamination of the Food Supply Chain—Implications for One Health Programme. Procedia Food Sci. 2015, 5, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, M.F.; Recote, J.M.; Van Camp, C.; Van Hassel, W.H.R.; Pedroni, L.; Dellafiora, L.; Masquelier, J.; Rajkovic, A. Potential (Co-)Contamination of Dairy Milk with AFM1 and MC-LR and Their Synergistic Interaction in Inducing Mitochondrial Dysfunction in HepG2 Cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2024, 192, 114907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskola, M.; Kos, G.; Elliott, C.T.; Hajšlová, J.; Mayar, S.; Krska, R. Worldwide Contamination of Food-Crops with Mycotoxins: Validity of the Widely Cited “FAO Estimate” of 25. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 2773–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint FAO/WHO Food Standards Programme Report of the 15th Session of the Codex Committee on Contaminants in Foods. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/es/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252FMeetings%252FCX-735-15%252FREPORT%252FFINAL%252520REPORT%252FREP22_CF15e.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Nicole, H. NCGA Expands National Mycotoxin Effort to Protect Corn Quality and Market Access; National Corn Growers Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Senerwa, D.M.; Sirma, A.J.; Mtimet, N.; Kang’ethe, E.K.; Grace, D.; Lindahl, J.F. Prevalence of Aflatoxin in Feeds and Cow Milk from Five Counties in Kenya. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2016, 16, 11004–11021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisvad, J.C.; Hubka, V.; Ezekiel, C.N.; Hong, S.-B.; Nováková, A.; Chen, A.J.; Arzanlou, M.; Larsen, T.O.; Sklenář, F.; Mahakarnchanakul, W.; et al. Taxonomy of Aspergillus Section Flavi and Their Production of Aflatoxins, Ochratoxins and Other Mycotoxins. Stud. Mycol. 2019, 93, 1–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IARC. Some Traditional Herbal Medicines, Some Mycotoxins, Naphthalene and Styrene; International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization, Eds.; IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2002; ISBN 978-92-832-1282-9. [Google Scholar]

- Messina, L.; Licata, P.; Bruno, F.; Litrenta, F.; Costa, G.L.; Ferrantelli, V.; Peycheva, K.; Panayotova, V.; Fazio, F.; Bruschetta, G.; et al. Occurrence and Health Risk Assessment of Mineral Composition and Aflatoxin M1 in Cow Milk Samples from Different Areas of Sicily, Italy. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2024, 85, 127478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Summa, S.; Lo Magro, S.; Vita, V.; Franchino, C.; Scopece, V.; D’Antini, P.; Iammarino, M.; De Pace, R.; Muscarella, M. Occurrence of Aflatoxin M1 in Raw and Processed Milk: A Contribution to Human Exposure Assessment After 12 Years of Investigation. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipoyan, D.; Hovhannisyan, A.; Beglaryan, M.; Mantovani, A. Risk Assessment of AFM1 in Raw Milk and Dairy Products Produced in Armenia, a Caucasus Region Country: A Pilot Study. Foods 2024, 13, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cary, J.W.; Ehrlich, K.C.; Bland, J.M.; Montalbano, B.G. The Aflatoxin Biosynthesis Cluster Gene, aflX, Encodes an Oxidoreductase Involved in Conversion of Versicolorin A to Demethylsterigmatocystin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 1096–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Ehrlich, K.C. Aflatoxin Biosynthetic Pathway and Pathway Genes. In Aflatoxins—Biochemistry and Molecular Biology; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011; pp. 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J. Current Understanding on Aflatoxin Biosynthesis and Future Perspective in Reducing Aflatoxin Contamination. Toxins 2012, 4, 1024–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagnollo, F.B.; Ganev, K.C.; Khaneghah, A.M.; Portela, J.B.; Cruz, A.G.; Granato, D.; Corassin, C.H.; Oliveira, C.A.F.; Sant’Ana, A.S. The Occurrence and Effect of Unit Operations for Dairy Products Processing on the Fate of Aflatoxin M1: A Review. Food Control 2016, 68, 310–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R. Mycotoxins in Food: Occurrence, Health Implications, and Control Strategies-A Comprehensive Review. Toxicon 2024, 248, 108038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahato, D.K.; Lee, K.E.; Kamle, M.; Devi, S.; Dewangan, K.N.; Kumar, P.; Kang, S.G. Aflatoxins in Food and Feed: An Overview on Prevalence, Detection and Control Strategies. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penagos-Tabares, F.; Mahmood, M.; Sulyok, M.; Rafique, K.; Khan, M.R.; Zebeli, Q.; Krska, R.; Metzler-Zebeli, B. Outbreak of Aflatoxicosis in a Dairy Herd Induced Depletion in Milk Yield and High Abortion Rate in Pakistan. Toxicon 2024, 246, 107799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassen, J.Y.; Debella, A.; Eyeberu, A.; Mussa, I. Prevalence and Concentration of Aflatoxin M1 in Breast Milk in Africa: A Meta-Analysis and Implication for the Interface of Agriculture and Health. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benkerroum, N. Aflatoxins: Producing-Molds, Structure, Health Issues and Incidence in Southeast Asian and Sub-Saharan African Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhaya, R.S.; Membré, J.-M.; Nag, R.; Cummins, E. Farm-to-Fork Risk Assessment of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk under Climate Change Scenarios—A Comparative Study of France and Ireland. Food Control 2023, 149, 109713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Hennessy, D.A.; Tack, J.; Wu, F. Climate Change Will Increase Aflatoxin Presence in US Corn. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 054017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilani, P.; Toscano, P.; Van Der Fels-Klerx, H.J.; Moretti, A.; Camardo Leggieri, M.; Brera, C.; Rortais, A.; Goumperis, T.; Robinson, T. Aflatoxin B1 Contamination in Maize in Europe Increases Due to Climate Change. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Li, X.; Xu, R.; Liu, S.; Rui, Z.; Guo, Z.; Chen, D. Bibliometric Analysis of Tuberculosis Molecular Epidemiology Based on CiteSpace. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1040176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baspakova, A.; Bazargaliyev, Y.S.; Kaliyev, A.A.; Mussin, N.M.; Karimsakova, B.; Akhmetova, S.Z.; Tamadon, A. Bibliometric Analysis of the Impact of ultra-processed Foods on the Gut Microbiota. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaoye, S.A.; Oladele, S.O.; Badmus, T.A.; Filani, I.; Jaiyeoba, F.K.; Sedara, A.M.; Olalusi, A.P. Thermal and Non-Thermal Pasturization of Citrus Fruits: A Bibliometrics Analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Wei, M.; Sheng, Y. A Bibliometric Analysis of Food Safety Governance Research from 1999 to 2019. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 9, 2316–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behtarin, P.; Movassaghghazani, M. Aflatoxin M1 Level and Risk Assessment in Milk, Yogurt, and Cheese in Tabriz, Iran. Toxicon 2024, 250, 108119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massahi, T.; Omer, A.K.; Habibollahi, M.H.; Mansouri, B.; Ebrahimzadeh, G.; Parnoon, K.; Soleimani, H.; Sharafi, K. Human Health Risk Assessment of Aflatoxin M1 in Various Dairy Products in Iran: A Literature Review. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 129, 106124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, Z.; Hamzeh Pour, S.; Ezati, P.; Akrami-Mohajeri, F. Determination of Aflatoxin M1 and Ochratoxin A in Breast Milk in Rural Centers of Yazd, Iran: Exposure Assessment and Risk Characterization. Mycotoxin Res. 2024, 40, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, M.; Solati, A.; Bahari, P.; Sharifan, M.; Valizadeh, T.; Shoraka, H. Aflatoxin M1 Contamination in Milk From North Khorasan Province: Raw vs Pasteurized vs Sterilized. J. Res. Health 2024, 14, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleibar, M.T.; Helan, J.A. A Field Outbreak of Aflatoxicosis with High Fatality Rate in Feedlot Calves in Iran. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2013, 22, 1155–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminianfar, H. A Report of Aflatoxicosis in Hand-Fed Ewe Lambs Exhibiting Icterus After Hepatic Failure and Hemoglobinuria. Iran. J. Vet. Med. 2024, 18, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Zeng, H.M.; Zheng, R.S.; Zhang, S.W.; Sun, K.X.; Zou, X.N.; Chen, R.; Wang, S.M.; Gu, X.Y.; Wei, W.W.; et al. Liver cancer epidemiology in China, 2015. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi 2019, 41, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Cao, M.; Wang, Y.; Bai, F.; Lei, L.; Peng, J.; Feletto, E.; Canfell, K.; Qu, C.; Chen, W. Is It Possible to Halve the Incidence of Liver Cancer in China by 2050? Int. J. Cancer 2021, 148, 1051–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamo, F.T.; Abate, B.A.; Zheng, Y.; Nie, C.; He, M.; Liu, Y. Distribution of Aspergillus Fungi and Recent Aflatoxin Reports, Health Risks, and Advances in Developments of Biological Mitigation Strategies in China. Toxins 2021, 13, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneely, J.P.; Kolawole, O.; Haughey, S.A.; Miller, S.J.; Krska, R.; Elliott, C.T. The Challenge of Global Aflatoxins Legislation with a Focus on Peanuts and Peanut Products: A Systematic Review. Expo. Health 2023, 15, 467–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, H.; Abbas, H.; Fisher, D.; Bellaloui, N. Relationship between Aflatoxin Contamination and Physiological Responses of Corn Plants under Drought and Heat Stress. Toxins 2012, 4, 1385–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, R.B.; Elsharkawy, E.E.; Sharkawy, A.A. Assessment of Aflatoxin M1 in Raw Milk Samples of Some Dairy Animals from Sohag City, Egypt. Nutr. Food Sci. 2024, 54, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismaiel, A.A.; Tharwat, N.A.; Sayed, M.A.; Gameh, S.A. Two-Year Survey on the Seasonal Incidence of Aflatoxin M1 in Traditional Dairy Products in Egypt. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 2182–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshannaq, A.; Yu, J.-H. Occurrence, Toxicity, and Analysis of Major Mycotoxins in Food. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, S.; Polo, A.; Ariano, A.; Velotto, S.; Costantini, S.; Severino, L. Aflatoxin B1 and M1: Biological Properties and Their Involvement in Cancer Development. Toxins 2018, 10, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrenk, D.; Bignami, M.; Bodin, L.; Chipman, J.K.; Del Mazo, J.; Wallace, H.; Schrenk, D.; Bignami, M.; Bodin, L.; Chipman, J.K.; et al. Risk Assessment of Aflatoxins in Food. EFSA J. 2020, 18, e06040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.A.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Z.; Li, X.; Saleemi, M.K.; He, C. Mycotoxin Contamination and Control Strategy in Human, Domestic Animal and Poultry: A Review. Microb. Pathog. 2020, 142, 104095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, A.; Gonçalves, B.L.; De Neeff, D.V.; Ponzilacqua, B.; Coppa, C.F.S.C.; Hintzsche, H.; Sajid, M.; Cruz, A.G.; Corassin, C.H.; Oliveira, C.A.F. Aflatoxin in Foodstuffs: Occurrence and Recent Advances in Decontamination. Food Res. Int. 2018, 113, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Flores, M.E.; Lizarraga, E.; López De Cerain, A.; González-Peñas, E. Presence of Mycotoxins in Animal Milk: A Review. Food Control 2015, 53, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.Z.; Jinap, S.; Pirouz, A.A.; Ahmad Faizal, A.R. Aflatoxin M1 in Milk and Dairy Products, Occurrence and Recent Challenges: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 46, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker-Algeri, T.A.; Castagnaro, D.; de Bortoli, K.; de Souza, C.; Drunkler, D.A.; Badiale-Furlong, E. Mycotoxins in Bovine Milk and Dairy Products: A Review. J. Food Sci. 2016, 81, R544–R552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corassin, C.H.; Borowsky, A.; Ali, S.; Rosim, R.E.; De Oliveira, C.A.F. Occurrence of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk and Dairy Products Traded in São Paulo, Brazil: An Update. Dairy 2022, 3, 842–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.; Levin, R.E.; Riaz, M.; Akhtar, S.; Gong, Y.Y.; De Oliveira, C.A.F. Effect of Different Microbial Concentrations on Binding of Aflatoxin M 1 and Stability Testing. Food Control 2017, 73, 492–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zentai, A.; Jóźwiak, Á.; Süth, M.; Farkas, Z. Carry-Over of Aflatoxin B1 from Feed to Cow Milk—A Review. Toxins 2023, 15, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorni, P.; Magan, N.; Pietri, A.; Bertuzzi, T.; Battilani, P. Studies on Aspergillus Section Flavi Isolated from Maize in Northern Italy. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2007, 113, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Jiang, L.; Xiao, L.; Kong, W. Physico-Chemical Characteristics and Aflatoxins Production of Atractylodis Rhizoma to Different Storage Temperatures and Humidities. AMB Expr. 2021, 11, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muga, F.C.; Marenya, M.O.; Workneh, T.S. Effect of Temperature, Relative Humidity and Moisture on Aflatoxin Contamination of Stored Maize Kernels. Bulg. J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 25, 271–277. [Google Scholar]

- Kemboi, D.C.; Antonissen, G.; Ochieng, P.E.; Croubels, S.; Okoth, S.; Kangethe, E.K.; Faas, J.; Lindahl, J.F.; Gathumbi, J.K. A Review of the Impact of Mycotoxins on Dairy Cattle Health: Challenges for Food Safety and Dairy Production in Sub-Saharan Africa. Toxins 2020, 12, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Pathak, H.; Bhadauria, S.; Sudan, J. Aflatoxin Contamination in Food Crops: Causes, Detection, and Management: A Review. Food Prod. Process Nutr. 2021, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaneian, M.T.; Jafari, A.; Jamshidi, S.; Ehrampoush, M.H.; Momeni, H.; Jamshidi, O.; Ghove, M.A. Survey the Frequency and Type of Fungal Contaminants in Animal Feed of Yazd Dairy Cattles. Iran. J. Anim. Sci. Res. 2015, 7, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Guan, X.; Xing, F.; Lv, C.; Dai, X.; Liu, Y. Effect of Water Activity and Temperature on the Growth of Aspergillus Flavus, the Expression of Aflatoxin Biosynthetic Genes and Aflatoxin Production in Shelled Peanuts. Food Control 2017, 82, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Code of Practice for the Prevention and Reduction of Aflatoxin Contamination in Cereals; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Prandini, A.; Tansini, G.; Sigolo, S.; Filippi, L.; Laporta, M.; Piva, G. On the Occurrence of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk and Dairy Products. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009, 47, 984–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valencia-Quintana, R.; Milić, M.; Jakšić, D.; Šegvić Klarić, M.; Tenorio-Arvide, M.G.; Pérez-Flores, G.A.; Bonassi, S.; Sánchez-Alarcón, J. Environment Changes, Aflatoxins, and Health Issues, a Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shabeer, S.; Asad, S.; Jamal, A.; Ali, A. Aflatoxin Contamination, Its Impact and Management Strategies: An Updated Review. Toxins 2022, 14, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milićević, D.; Petronijević, R.; Petrović, Z.; Đjinović-Stojanović, J.; Jovanović, J.; Baltić, T.; Janković, S. Impact of Climate Change on Aflatoxin M1 Contamination of Raw Milk with Special Focus on Climate Conditions in Serbia. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 5202–5210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolosa, J.; Rodríguez-Carrasco, Y.; Ruiz, M.J.; Vila-Donat, P. Multi-Mycotoxin Occurrence in Feed, Metabolism and Carry-over to Animal-Derived Food Products: A Review. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 158, 112661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stella, R.; Bovo, D.; Noviello, S.; Contiero, L.; Barberio, A.; Angeletti, R.; Biancotto, G. Fate of Aflatoxin M1 from Milk to Typical Italian Cheeses: Validation of an HPLC Method Based on Aqueous Buffer Extraction and Immune-Affinity Clean up with Limited Use of Organic Solvents. Food Control 2024, 157, 110149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi Khaneghah, A.; Moosavi, M.; Omar, S.S.; Oliveira, C.A.F.; Karimi-Dehkordi, M.; Fakhri, Y.; Huseyn, E.; Nematollahi, A.; Farahani, M.; Sant’Ana, A.S. The Prevalence and Concentration of Aflatoxin M1 among Different Types of Cheeses: A Global Systematic Review, Meta-Analysis, and Meta-Regression. Food Control 2021, 125, 107960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britzi, M.; Friedman, S.; Miron, J.; Solomon, R.; Cuneah, O.; Shimshoni, J.; Soback, S.; Ashkenazi, R.; Armer, S.; Shlosberg, A. Carry-Over of Aflatoxin B1 to Aflatoxin M1 in High Yielding Israeli Cows in Mid- and Late-Lactation. Toxins 2013, 5, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, R.O.; Rodrigues, R.O.; Ledoux, D.R.; Rottinghaus, G.E.; Borutova, R.; Averkieva, O.; McFadden, T.B. Feed Additives Containing Sequestrant Clay Minerals and Inactivated Yeast Reduce Aflatoxin Excretion in Milk of Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 6614–6623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahbazi, Y.; Nikousefat, Z.; Karami, N. Occurrence, Seasonal Variation and Risk Assessment of Exposure to Aflatoxin M 1 in Iranian Traditional Cheeses. Food Control 2017, 79, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilandžić, N.; Varenina, I.; Kolanović, B.S.; Božić, Đ.; Đokić, M.; Sedak, M.; Tanković, S.; Potočnjak, D.; Cvetnić, Ž. Monitoring of Aflatoxin M1 in Raw Milk during Four Seasons in Croatia. Food Control 2015, 54, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomašević, I.; Petrović, J.; Jovetić, M.; Raičević, S.; Milojević, M.; Miočinović, J. Two Year Survey on the Occurrence and Seasonal Variation of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk and Milk Products in Serbia. Food Control 2015, 56, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour, S.H.; Mahmoudi, S.; Masoumi, S.; Rezaie, S.; Barac, A.; Ranjbaran, M.; Oliya, S.; Mehravar, F.; Sasani, E.; Noorbakhsh, F.; et al. Aflatoxin M1 Contamination Level in Iranian Milk and Dairy Products: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Mycotoxin J. 2020, 13, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, J.-S.; Ji, J.; Ning, X.; Sun, X. Antibiotic Altered Liver Damage Induced by Aflatoxin B1 Exposure in Mice by Modulating the Gut Microbiota. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 343, 123291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulzberger, S.A.; Melnichenko, S.; Cardoso, F.C. Effects of Clay after an Aflatoxin Challenge on Aflatoxin Clearance, Milk Production, and Metabolism of Holstein Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 1856–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ogunade, I.M.; Vyas, D.; Adesogan, A.T. Aflatoxin in Dairy Cows: Toxicity, Occurrence in Feedstuffs and Milk and Dietary Mitigation Strategies. Toxins 2021, 13, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capriotti, A.L.; Caruso, G.; Cavaliere, C.; Foglia, P.; Samperi, R.; Laganà, A. Multiclass Mycotoxin Analysis in Food, Environmental and Biological Matrices with Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry. Mass. Spectrom. Rev. 2012, 31, 466–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, L.T.; Ismail, A.; Amjad, A.; Oliveira, C.A.F.D. Occurrence of Toxigenic Fungi and Mycotoxins in Workplaces and Human Biomonitoring of Mycotoxins in Exposed Workers: A Systematic Review. Toxin Rev. 2021, 40, 576–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azziz-Baumgartner, E.; Lindblade, K.; Gieseker, K.; Rogers, H.S.; Kieszak, S.; Njapau, H.; Schleicher, R.; McCoy, L.F.; Misore, A.; DeCock, K.; et al. Case–Control Study of an Acute Aflatoxicosis Outbreak, Kenya, 2004. Environ. Health Perspect 2005, 113, 1779–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Ghazali, F.M.; Mahyudin, N.A.; Samsudin, N.I.P. Biocontrol of Aflatoxins Using Non-Aflatoxigenic Aspergillus Flavus: A Literature Review. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherif, S.O.; Salama, E.E.; Abdel-Wahhab, M.A. Mycotoxins and Child Health: The Need for Health Risk Assessment. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2009, 212, 347–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-W.; Gao, Y.-N.; Huang, S.-N.; Wang, J.-Q.; Zheng, N. Ex Vivo and In Vitro Studies Revealed Underlying Mechanisms of Immature Intestinal Inflammatory Responses Caused by Aflatoxin M1 Together with Ochratoxin A. Toxins 2022, 14, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güç, İ.; Yalçin, E.; Çavuşoğlu, K.; Acar, A. Toxicity Mechanisms of Aflatoxin M1 Assisted with Molecular Docking and the Toxicity-Limiting Role of Trans-Resveratrol. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhaya, R.S.; Nag, R.; Cummins, E. Human Health Risk from Co-Occurring Mycotoxins in Dairy: A Feed-to-Fork Approach. Food Control 2025, 168, 110954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njombwa, C.A.; Moreira, V.; Williams, C.; Aryana, K.; Matumba, L. Aflatoxin M1 in Raw Cow Milk and Associated Hepatocellular Carcinoma Risk among Dairy Farming Households in Malawi. Mycotoxin Res. 2021, 37, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaridi, J.; Bassil, M.; Kharma, J.A.; Daou, F.; Hassan, H.F. Analysis of Aflatoxin M1 in Breast Milk and Its Association with Nutritional and Socioeconomic Status of Lactating Mothers in Lebanon. J. Food Prot. 2017, 80, 1737–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaridi, J.; Dimassi, H.; Hassan, H. Aflatoxin M1 and Ochratoxin A in Baby Formulae Marketed in Lebanon: Occurrence and Safety Evaluation. Food Control 2019, 106, 106680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movassaghghazani, M.; Shabansalmani, N. Assessment of Aflatoxin M1 in Human Breast and Powdered Milk in Tehran, Iran. Toxicon 2024, 237, 107530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benkerroum, N.; Ismail, A. Human Breast Milk Contamination with Aflatoxins, Impact on Children’s Health, and Possible Control Means: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.; Pokharel, A.; Scott, C.K.; Wu, F. Aflatoxin M1 in Milk and Dairy Products: The State of the Evidence for Child Growth Impairment. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2024, 193, 115008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortei, N.K.; Annan, T.; Kyei-Baffour, V.; Essuman, E.K.; Boakye, A.A.; Tettey, C.O.; Boadi, N.O. Exposure Assessment and Cancer Risk Characterization of Aflatoxin M1 (AFM1) through Ingestion of Raw Cow Milk in Southern Ghana. Toxicol. Rep. 2022, 9, 1189–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torović, L.; Popov, N.; Živkov-Baloš, M.; Jakšić, S. Risk Estimates of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Vojvodina (Serbia) Related to Aflatoxin M1 Contaminated Cheese. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2021, 103, 104122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirma, A.; Makita, K.; Grace Randolph, D.; Senerwa, D.; Lindahl, J. Aflatoxin Exposure from Milk in Rural Kenya and the Contribution to the Risk of Liver Cancer. Toxins 2019, 11, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortezazadeh, F.; Gholami-Borujeni, F. Review, Meta-Analysis and Carcinogenic Risk Assessment of Aflatoxin M1 in Different Types of Milks in Iran. Rev. Environ. Health 2023, 38, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, A.; Akhtar, S.; Levin, R.E.; Ismail, T.; Riaz, M.; Amir, M. Aflatoxin M1: Prevalence and Decontamination Strategies in Milk and Milk Products. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 42, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. CPG Sec. 527.400—Whole Milk, Lowfat Milk, Skim Milk—Aflatoxin M1; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2015.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. CPG Sec. 683.100—Action Levels for Aflatoxins in Animal Feeds; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2019.

- Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/sh-proxy/en/?lnk=1&url=https%253A%252F%252Fworkspace.fao.org%252Fsites%252Fcodex%252Fstandards%252FCXS%2B193-1995%252FCXS_193e.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Frey, M.; Rosim, R.; Oliveira, C. Mycotoxin Co-Occurrence in Milks and Exposure Estimation: A Pilot Study in São Paulo, Brazil. Toxins 2021, 13, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Zheng, N.; Gao, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, J. Safety and Quality Evaluations of Liquid Milk and Infant Formula Products in China in 2022. Anim. Res. One Health 2023, 1, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattimare, D.; Shakya, S.; Patyal, A.; Chandrakar, C.; Kumar, A. Occurrence and Exposure Assessment of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk and Milk Products in India. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 59, 2460–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuhu, A.H.; Dorleku, W.-P.; Blay, B.; Derban, E.; McArthur, C.O.; Alobuia, S.E.; Incoom, A.; Dontoh, D.; Ofosu, I.W.; Oduro-Mensah, D. Exposure to Aflatoxins and Ochratoxin A from the Consumption of Selected Staples and Fresh Cow Milk in the Wet and Dry Seasons in Ghana. Food Control 2025, 168, 110968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Union. European Commission Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/915 of 25 April 2023 on Maximum Levels for Certain Contaminants in Food and Repealing Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 2023; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- Malissiova, E.; Tsinopoulou, G.; Gerovasileiou, E.S.; Meleti, E.; Soultani, G.; Koureas, M.; Maisoglou, I.; Manouras, A. A 20-Year Data Review on the Occurrence of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk and Dairy Products in Mediterranean Countries—Current Situation and Exposure Risks. Dairy 2024, 5, 491–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.D. Over-Regulation of Aflatoxin M1 Is Expensive and Harmful in Food-Insecure Countries. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 115, 1451–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinedine, A.; Ben Salah-Abbes, J.; Abbès, S.; Tantaoui-Elaraki, A. Aflatoxin M1 in Africa: Exposure Assessment, Regulations, and Prevention Strategies—A Review. In Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 73–108. ISBN 978-3-030-88325-6. [Google Scholar]

- Jahromi, A.S.; Jokar, M.; Abdous, A.; Rabiee, M.H.; Biglo, F.H.B.; Rahmanian, V. Prevalence and Concentration of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk and Dairy Products: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses. Int. Health 2025, 17, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Flores, M.E.; González-Peñas, E. Short Communication: Analysis of Mycotoxins in Spanish Milk. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinyemi, M.O.; Braun, D.; Windisch, P.; Warth, B.; Ezekiel, C.N. Assessment of Multiple Mycotoxins in Raw Milk of Three Different Animal Species in Nigeria. Food Control 2022, 131, 108258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousof, S.S.M.; El Zubeir, I.E.M. Chemical Composition and Detection of Aflatoxin M1 in Camels and Cows Milk in Sudan. Food Addit. Contam. Part B 2020, 13, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewida, R.M.; Ali, M.A.; Hussein, M.S.A.; Abdel-Maguid, D.S.M. Detection of Aflatoxins and Novel Simple Regimes for Their Detoxification in Milk and Soft Cheese. J. Adv. Vet. Res. 2024, 14, 1016–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Tarannum, N.; Nipa, M.N.; Das, S.; Parveen, S. Aflatoxin M1 Detection by ELISA in Raw and Processed Milk in Bangladesh. Toxicol. Rep. 2020, 7, 1339–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez, S.; Théolier, J.; Daou, R.; Godefroy, S.B.; Hoteit, M.; El Khoury, A. Stochastic Health Risk Assessment of Aflatoxin M1 in Cow’s Milk among Lebanese Population. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2024, 193, 115042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, H.F.; Kassaify, Z. The Risks Associated with Aflatoxins M1 Occurrence in Lebanese Dairy Products. Food Control 2014, 37, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, A.W.; Lindahl, J.F.; Anwar, Z.; Ullah, A.; Ibrahim, M.N.M. Farmer’s Knowledge and Suggested Approaches for Controlling Aflatoxin Contamination of Raw Milk in Pakistan. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 980105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roila, R.; Branciari, R.; Verdini, E.; Ranucci, D.; Valiani, A.; Pelliccia, A.; Fioroni, L.; Pecorelli, I. A Study of the Occurrence of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk Supply Chain over a Seven-Year Period (2014–2020): Human Exposure Assessment and Risk Characterization in the Population of Central Italy. Foods 2021, 10, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Khoury, A.; Atoui, A.; Yaghi, J. Analysis of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk and Yogurt and AFM1 Reduction by Lactic Acid Bacteria Used in Lebanese Industry. Food Control 2011, 22, 1695–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govaris, A.; Roussi, V.; Koidis, P.A.; Botsoglou, N.A. Distribution and Stability of Aflatoxin M1 during Production and Storage of Yoghurt. Food Addit. Contam. 2002, 19, 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumon, A.H.; Islam, F.; Mohanto, N.C.; Kathak, R.R.; Molla, N.H.; Rana, S.; Degen, G.H.; Ali, N. The Presence of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk and Milk Products in Bangladesh. Toxins 2021, 13, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.M.D.M.; Da Cruz, A.G.; Ali, S.; Freire, L.G.D.; Fonseca, L.M.; Rosim, R.E.; Corassin, C.H.; Oliveira, R.B.A.D.; Oliveira, C.A.F.D. Incidence and Levels of Aflatoxin M1 in Artisanal and Manufactured Cheese in Pernambuco State, Brazil. Toxins 2023, 15, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conteçotto, A.C.T.; Pante, G.C.; Castro, J.C.; Souza, A.A.; Lini, R.S.; Romoli, J.C.Z.; Abreu Filho, B.A.; Mikcha, J.M.G.; Mossini, S.A.G.; Machinski Junior, M. Occurrence, Exposure Evaluation and Risk Assessment in Child Population for Aflatoxin M1 in Dairy Products in Brazil. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 148, 111913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Chen, F.; Zhang, J.; Ao, W.; Zhou, X.; Yang, H.; Wu, Z.; Wu, L.; Wang, C.; Qiu, Y. Occurrence of Aflatoxin M1 in Three Types of Milk from Xinjiang, China, and the Risk of Exposure for Milk Consumers in Different Age-Sex Groups. Foods 2022, 11, 3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilandžić, N.; Varga, I.; Varenina, I.; Solomun Kolanović, B.; Božić Luburić, Đ.; Đokić, M.; Sedak, M.; Cvetnić, L.; Cvetnić, Ž. Seasonal Occurrence of Aflatoxin M1 in Raw Milk during a Five-Year Period in Croatia: Dietary Exposure and Risk Assessment. Foods 2022, 11, 1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.; Awad, S.; Elsenduony, M. Assessment of Some Chemical Residues in Egyptian Raw Milk and Traditional Cheese. Open Vet. J. 2024, 14, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortei, N.K.; Gillette, V.S.; Wiafe-Kwagyan, M.; Ansah, L.O.; Kyei-Baffour, V.; Odamtten, G.T. Fungal Profile, Levels of Aflatoxin M1, Exposure, and the Risk Characterization of Local Cheese ‘Wagashi’ Consumed in the Ho Municipality, Volta Region, Ghana. Toxicol. Rep. 2024, 12, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggira, M.; Ioannidou, M.; Sakaridis, I.; Samouris, G. Determination of Aflatoxin M1 in Raw Milk Using an HPLC-FL Method in Comparison with Commercial ELISA Kits—Application in Raw Milk Samples from Various Regions of Greece. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzás, H.; Szabó-Sárvári, L.C.; Szabó, K.; Nagy-Kovács, K.; Bukovics, S.; Süle, J.; Szafner, G.; Hucker, A.; Kocsis, R.; Kovács, A.J. Aflatoxin M1 Detection in Raw Milk and Drinking Milk in Hungary by ELISA − A One-Year Survey. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 121, 105368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghebatbinyeganeh, K.; Movassaghghazani, M.; Abdallah, M.F. Seasonal Variation and Risk Assessment of Exposure to Aflatoxin M1 in Milk, Yoghurt, and Cheese Samples from Ilam and Lorestan Provinces of Iran. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 128, 106083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorjani, R.; Movassaghghazani, M. Determination of Aflatoxin M1 in Raw Cow Milk, Raw Camel Milk, and Heat-Processed Milk in the North Region of Iran. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2024, 81, 1114–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, L.; Rizzi, N.; Grandi, E.; Clerici, E.; Tirloni, E.; Stella, S.; Bernardi, C.E.M.; Pinotti, L. Compliance between Food and Feed Safety: Eight-Year Survey (2013–2021) of Aflatoxin M1 in Raw Milk and Aflatoxin B1 in Feed in Northern Italy. Toxins 2023, 15, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.C.; Stringer, A.; Owuor, K.O.; Ndenga, B.A.; Winter, C.; Gerken, K.N. Moving Milk and Shifting Risk: A Mixed Methods Assessment of Food Safety Risks along Informal Dairy Value Chains in Kisumu, Kenya. One Health 2024, 19, 100914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, J.F.; Kagera, I.N.; Grace, D. Aflatoxin M1 Levels in Different Marketed Milk Products in Nairobi, Kenya. Mycotoxin Res. 2018, 34, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoteit, M.; Abbass, Z.; Daou, R.; Tzenios, N.; Chmeis, L.; Haddad, J.; Chahine, M.; Al Manasfi, E.; Chahine, A.; Poh, O.B.J.; et al. Dietary Exposure and Risk Assessment of Multi-Mycotoxins (AFB1, AFM1, OTA, OTB, DON, T-2 and HT-2) in the Lebanese Food Basket Consumed by Adults: Findings from the Updated Lebanese National Consumption Survey through a Total Diet Study Approach. Toxins 2024, 16, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-Días, F.; Torres-Parga, B.; Valdivia-Flores, A.G.; Quezada-Tristán, T.; Alejos-De La Fuente, J.I.; Sosa-Ramírez, J.; Rangel-Muñoz, E.J. Aspergillus Flavus and Total Aflatoxins Occurrence in Dairy Feed and Aflatoxin M1 in Bovine Milk in Aguascalientes, Mexico. Toxins 2022, 14, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Nasir, A.; Kashif, M.; Sikandar, A.; Sajid, M.; Adil, M.; Rehman, A.; Iqbal, M.; Ullah, H. Incidence of Aflatoxin M1 in Cows’ Milk in Pakistan, Effects on Milk Quality and Evaluation of Therapeutic Management in Dairy Animals. Vet. Med. 2023, 68, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djekic, I.; Petrovic, J.; Jovetic, M.; Redzepovic-Djordjevic, A.; Stulic, M.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Iammarino, M.; Tomasevic, I. Aflatoxins in Milk and Dairy Products: Occurrence and Exposure Assessment for the Serbian Population. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Cañás, I.; González-Jartín, J.M.; Alvariño, R.; Alfonso, A.; Vieytes, M.R.; Botana, L.M. Identification of Mycotoxins in Yogurt Samples Using an Optimized QuEChERS Extraction and UHPLC-MS/MS Detection. Mycotoxin Res. 2024, 40, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ergin, S.; Çakmak, Ö.; Çakmak, T.; Acaröz, U.; Yalçın, H.; Acaröz, D.; İnce, S. Determination of Aflatoxin M1 Levels in Turkish Cheeses Provided from Different Regions of Turkey. J. Hell. Vet. Med. Soc. 2023, 74, 5211–5218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q. Decontamination of Aflatoxin B1. In Aflatoxin B1 Occurrence, Detection and Toxicological Effects; Long, X.-D., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-1-83880-255-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kutasi, K.; Recek, N.; Zaplotnik, R.; Mozetič, M.; Krajnc, M.; Gselman, P.; Primc, G. Approaches to Inactivating Aflatoxins—A Review and Challenges. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, G.S.; Price, R.L.; Park, D.L.; Hendricks, J.D. Effect of Ammoniation of Aflatoxin B1-Contaminated Cottonseed Feedstock on the Aflatoxin M1 Content of Cows’ Milk and Hepatocarcinogenicity in the Trout Bioassay. Food Chem. Toxicol. 1994, 32, 707–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrenk, D.; Bignami, M.; Bodin, L.; Chipman, J.K.; del Mazo, J.; Grasl-Kraupp, B.; Hoogenboom, L.R.; Leblanc, J.; Nebbia, C.S.; et al.; EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM) Assessment of an Application on a Detoxification Process of Groundnut Press Cake for Aflatoxins by Ammoniation. EFSA J. 2021, 19, e07035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Jiao, P.; Wang, X.; Sun, Y.; Liang, G.; Xie, X.; Zhang, Y. Evaluation of Growth Performance, Nitrogen Balance and Blood Metabolites of Mutton Sheep Fed an Ammonia-Treated Aflatoxin B1-Contaminated Diet. Toxins 2022, 14, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Gao, L.; Li, Z.; Mao, G.; Zhang, H.; Wang, F.; Lam, S.S.; Song, A. Instant Catapult Steam Explosion Combined with Ammonia Water: A Complex Technology for Detoxification of Aflatoxin-Contaminated Peanut Cake with the Aim of Producing a Toxicity-Free and Nutrients Retention of Animal Feed. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fremy, J.M.; Gautier, J.P.; Herry, M.P.; Terrier, C.; Calett, C. Effects of Ammoniation on the ‘Carry-over’ of Aflatoxins into Bovine Milk. Food Addit. Contam. 1988, 5, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogenboom, L.A.P.; Tulliez, J.; Gautier, J.-P.; Coker, R.D.; Melcion, J.-P.; Nagler, M.J.; Polman, T.H.G.; Delort-Laval, J. Absorption, Distribution and Excretion of Aflatoxin-Derived Ammoniation Products in Lactating Cows. Food Addit. Contam. 2001, 18, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agriopoulou, S.; Koliadima, A.; Karaiskakis, G.; Kapolos, J. Kinetic Study of Aflatoxins’ Degradation in the Presence of Ozone. Food Control 2016, 61, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallakian, S.; Rezanezhad, R.; Jalali, M.; Ghobadi, F. The effect of ozone gas on destruction and detoxification of aflatoxin. Bull. Soc. Roy. Sc. Liège 2017, 86, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, H.; Mazloomi, S.M.; Eskandari, M.H.; Aminlari, M.; Niakousari, M. The Effect of Ozone on Aflatoxin M1, Oxidative Stability, Carotenoid Content and the Microbial Count of Milk. Ozone Sci. Eng. 2017, 39, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sert, D.; Mercan, E. Effects of Ozone Treatment to Milk and Whey Concentrates on Degradation of Antibiotics and Aflatoxin and Physicochemical and Microbiological Characteristics. LWT 2021, 144, 111226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto, Y.D.; Trombete, F.M.; Freitas-Silva, O.; De Castro, I.M.; Direito, G.M.; Ascheri, J.L.R. Gaseous Ozonation to Reduce Aflatoxins Levels and Microbial Contamination in Corn Grits. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, A.; Hajihosseini, R.; MahmoudiMeymand, M. Optimization of Ozonation Method for Reduction of Aflatoxin B1 in Ground Corn and Its Impact on Other Mycotoxins. J. Food Bioprocess. Eng. 2024, 7, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoori, E.; Hakimzadeh, V.; Mohammadi Sani, A.; Rashidi, H. Effect of Ozonation, UV Light Radiation, and Pulsed Electric Field Processes on the Reduction of Total Aflatoxin and Aflatoxin M1 in Acidophilus Milk. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, e14729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolarič, L.; Rusinková, K.; Šimko, P. Characterization of the Physicochemical Procedure of Aflatoxin M1 Elimination from Ringer’s Solution as a Model System and Raw Milk Using Beta-Cyclodextrin Polymer. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 101395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applebaum, R.S.; Marth, E.H. Inactivation of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk Using Hydrogen Peroxide and Hydrogen Peroxide plus Riboflavin or Lactoperoxidase. J. Food Prot. 1982, 45, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousef, A.E.; Marth, E.H. Use of Ultraviolet Energy to Degrade Aflatoxin M1 in Raw or Heated Milk with and Without Added Peroxide. J. Dairy Sci. 1986, 69, 2243–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.-H.; Singh, R.K. Detoxifying Aflatoxin Contaminated Peanuts by High Concentration of H2O2 at Moderate Temperature and Catalase Inactivation. Food Control 2022, 142, 109218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.T.; Nadeem, M.; Imran, M.; Ullah, R.; Ajmal, M.; Jaspal, M.H. Antioxidant Properties of Milk and Dairy Products: A Comprehensive Review of the Current Knowledge. Lipids Health Dis. 2019, 18, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidegger, D.; Larsen, G.; Kivatinitz, S.C. Oxidative Consequences of UV Irradiation on Isolated Milk Proteins: Effects of Hydrogen Peroxide and Bivalent Metal Ions. Int. Dairy J. 2016, 55, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Flint, S.; Palmer, J. Control of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk by Novel Methods: A Review. Food Chem. 2020, 311, 125984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.-H.; Singh, R.K. Detoxification of Aflatoxins in Foods by Ultraviolet Irradiation, Hydrogen Peroxide, and Their Combination—A Review. LWT 2021, 142, 110986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Additives and Products or Substances used in Animal Feed (FEEDAP); Rychen, G.; Aquilina, G.; Azimonti, G.; Bampidis, V.; Bastos, M.D.L.; Bories, G.; Chesson, A.; Cocconcelli, P.S.; Flachowsky, G.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Bentonite as a Feed Additive for All Animal Species. EFS2 2017, 15, e05096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, G.M.; El-Makarem, H.S.A.; Allam, M.G.; El Okle, O.S.; El-Toukhy, M.I.; Mehany, T.; El-Halmouch, Y.; Abushaala, M.M.F.; Saad, M.S.; Korma, S.A.; et al. Evaluation of the Adsorption Efficacy of Bentonite on Aflatoxin M1 Levels in Contaminated Milk. Toxins 2023, 15, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Hearon, S.E.; Phillips, T.D. A High Capacity Bentonite Clay for the Sorption of Aflatoxins. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2020, 37, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Velázquez, A.L.B.; Billes, F.; Dixon, J.B. Bonding Mechanisms between Aflatoxin B1 and Smectite. Appl. Clay Sci. 2010, 50, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, G.A.; Khattab, H.M.; Abdel-Wahhab, M.A.; Abo El-Nor, S.A.; El-Sayed, H.M.; Kholif, S.M. Clay Minerals as Sorbents for Mycotoxins in Lactating Goat’s Diets: Intake, Digestibility, Blood Chemistry, Ruminal Fermentation, Milk Yield and Composition, and Milk Aflatoxin M1 Content. Small Rumin. Res. 2019, 175, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyango, G.; Kagera, I.; Mutua, F.; Kahenya, P.; Kyallo, F.; Andang’o, P.; Grace, D.; Lindahl, J.F. Effectiveness of Training and Use of Novasil Binder in Mitigating Aflatoxins in Cow Milk Produced in Smallholder Farms in Urban and Periurban Areas of Kenya. Toxins 2021, 13, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maki, C.R.; Monteiro, A.P.A.; Elmore, S.E.; Tao, S.; Bernard, J.K.; Harvey, R.B.; Romoser, A.A.; Phillips, T.D. Calcium Montmorillonite Clay in Dairy Feed Reduces Aflatoxin Concentrations in Milk without Interfering with Milk Quality, Composition or Yield. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2016, 214, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M.S.; Di Domenico, D.; Thomaz, G.R.; Garbossa, G.; Depaoli, C.R.; Abreu, A.C.A.; Bertagnon, H.G. Effect of Bentonite on the Health and Dairy Production of Cows Submitted to a Diet Naturally Contaminated by Mycotoxins. Semin. Ciênc. Agrár 2021, 42, 3337–3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihal, A.; Rodríguez-Prado, M.; Calsamiglia, S. A Network Meta-Analysis on the Efficacy of Different Mycotoxin Binders to Reduce Aflatoxin M1 in Milk after Aflatoxin B1 Challenge in Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 5379–5387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soufiani, G.R.N.; Razmara, M.; Kermanshahi, H.; Barrientos Velázquez, A.L.; Daneshmand, A. Assessment of Aflatoxin B 1 Adsorption Efficacy of Natural and Processed Bentonites: In Vitro and in Vivo Assays. Appl. Clay Sci. 2016, 123, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajmohammadi, M.; Valizadeh, R.; Naserian, A.; Nourozi, M.E.; Oliveira, C.A.F. Effect of Size Fractionation of a Raw Bentonite on the Excretion Rate of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk from Dairy Cows Fed with Aflatoxin B1. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2021, 74, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahimi Khoram Abadi, E.; Heydari, S.; Kazemi, M. Dietary Incorporation of Magnetic Bentonite Nanocomposite: Impacts on in Vitro Fermentation Pattern Nutrient Digestibility and Growth Performance of Baluchi Male Lambs. Iran. J. Vet. Res. 2024, 25, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muaz, K.; Riaz, M. Decontamination of Aflatoxin M1 in milk through integration of microbial cells with sorbitan monostearate, activated carbon and bentonite. J. Anim. Plant Sci. 2020, 31, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muaz, K.; Riaz, M.; Oliveira, C.A.F.D.; Ismail, A.; Akhtar, S.; Nadeem, H.; Waseem, S.; Ahmed, Z. Aflatoxin M1 Removal from Milk Using Activated Carbon and Bentonite Combined with Lactic Acid Bacteria Cells. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2024, 77, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussa, A.I. Efficacy of Kaolin and Bentonite Clay to Reduce Aflatoxin M1 Content in Contaminated Milk and Effects on Milk Quality. Pak. Vet. J. 2020, 40, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelnaby, A.; Abdelaleem, N.M.; Elshewy, E.; Mansour, A.H.; Ibrahim, S. The Efficacy of Clay Bentonite, Date Pit, and Chitosan Nanoparticles in the Detoxification of Aflatoxin M1 and Ochratoxin A from Milk. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 20305–20317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, T.D.; Wang, M.; Elmore, S.E.; Hearon, S.; Wang, J.S. NovaSil clay for the protection of humans and animals from aflatoxins and other contaminants. Clays Clay Miner. 2019, 67, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naveed, S.; Chohan, K.; Jabbar, M.; Ditta, Y.; Ahmed, S.; Ahmad, N.; Akhtar, R. Aflatoxin M1 in Nili-Ravi Buffaloes and Its Detoxification Using Organic and Inorganic Toxin Binders. J. Hell. Vet. Med. Soc. 2018, 69, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, N.; Rodrigues, I.; McGill, D.M.; Warriach, H.M.; Cowling, A.; Haque, A.; Wynn, P.C. Transfer of Aflatoxins from Naturally Contaminated Feed to Milk of Nili-Ravi Buffaloes Fed a Mycotoxin Binder. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2016, 56, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.L.; Wang, Y.M.; Nennich, T.D.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.X. Transfer of Dietary Aflatoxin B1 to Milk Aflatoxin M1 and Effect of Inclusion of Adsorbent in the Diet of Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 2545–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsoulos, P.D.; Karatzia, M.A.; Boscos, C.; Wolf, P.; Karatzias, H. In-Field Evaluation of Clinoptilolite Feeding Efficacy on the Reduction of Milk Aflatoxin M1 Concentration in Dairy Cattle. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2016, 58, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, M.; Wang, E.; Hao, Y.; Ji, S.; Huang, S.; Zhao, L.; Wang, W.; Shao, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, S. Adsorbents Reduce Aflatoxin M1 Residue in Milk of Healthy Dairy Cow Exposed to Moderate Level Aflatoxin B1 in Diet and Its Exposure Risk for Humans. Toxins 2021, 13, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costamagna, D.; Gaggiotti, M.; Smulovitz, A.; Abdala, A.; Signorini, M. Mycotoxin Sequestering Agent: Impact on Health and Performance of Dairy Cows and Efficacy in Reducing AFM1 Residues in Milk. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2024, 105, 104349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradian, M.; Faraji, A.R.; Davood, A. Removal of Aflatoxin B1 from Contaminated Milk and Water by Nitrogen/Carbon-Enriched Cobalt Ferrite -Chitosan Nanosphere: RSM Optimization, Kinetic, and Thermodynamic Perspectives. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 256, 127863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nešić, K.; Habschied, K.; Mastanjević, K. Possibilities for the Biological Control of Mycotoxins in Food and Feed. Toxins 2021, 13, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massoud, R.; Zoghi, A. Potential Probiotic Strains with Heavy Metals and Mycotoxins Bioremoval Capacity for Application in Foodstuffs. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 133, 1288–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezasoltani, S.; Amir Ebrahimi, N.; Khadivi Boroujeni, R.; Asadzadeh Aghdaei, H.; Norouzinia, M. Detoxification of Aflatoxin M1 by Probiotics Saccharomyces Boulardii, Lactobacillus Casei, and Lactobacillus Acidophilus in Reconstituted Milk. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Bed Bench 2022, 15, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erfanpoor, M.; Noori, N.; Gandomi, H.; Azizian, A. Reduction and Binding of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk by Lactobacillus Plantarum and Lactobacillus Brevis Isolated from Siahmazgi Cheese. Toxin Rev. 2024, 43, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, H.J.; Patel, A.R. Removal of Aflatoxin M1 from Milk and Aqueous Medium by Indigenously Isolated Strains of W. Confusa H1 and L. Plantarum S2. Food Biosci. 2022, 45, 101468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muaz, K.; Riaz, M.; Rosim, R.E.; Akhtar, S.; Corassin, C.H.; Gonçalves, B.L.; Oliveira, C.A.F. In Vitro Ability of Nonviable Cells of Lactic Acid Bacteria Strains in Combination with Sorbitan Monostearate to Bind to Aflatoxin M1 in Skimmed Milk. LWT 2021, 147, 111666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosallaie, F.; Jooyandeh, H.; Hojjati, M.; Fazlara, A. Biological Reduction of Aflatoxin B1 in Yogurt by Probiotic Strains of Lactobacillus Acidophilus and Lactobacillus Rhamnosus. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 29, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyedjafarri, S. Detoxification of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk by Lactic Acid Bacteria. Asian J. Dairy Food Res. 2021, 40, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Nazari, R.R.; Rezaei, M.; Moazzen, M.; Shariatifar, N. Machine Learning for Detoxification of Aflatoxin M1 by Lactococcus Lactis Probiotic in Kashk Production. Food Saf. Risk 2025, 12, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaf, J.C.; El Khoury, A.; Atoui, A.; Louka, N.; Chokr, A. A Novel Technique for Aflatoxin M1 Detoxification Using Chitin or Treated Shrimp Shells: In Vitro Effect of Physical and Kinetic Parameters on the Binding Stability. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 6687–6697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Mendoza, A.; Guzman-de-Peña, D.; Garcia, H.S. Key Role of Teichoic Acids on Aflatoxin B1 Binding by Probiotic Bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 107, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anvar, A.; Khadivi, R.; Razavilar, V.; Akbari Adreghani, B. Binding of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Saccharomyces Boulardii Strains to Aflatoxin M1 in Experimentally Contaminated Milk Treated with Biophysical Factors. Arch. Razi Inst. 2020, 75, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotrowska, M.; Masek, A. Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Cell Wall Components as Tools for Ochratoxin A Decontamination. Toxins 2015, 7, 1151–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corassin, C.H.; Bovo, F.; Rosim, R.E.; Oliveira, C.A.F. Efficiency of Saccharomyces Cerevisiae and Lactic Acid Bacteria Strains to Bind Aflatoxin M1 in UHT Skim Milk. Food Control 2013, 31, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, B.L.; Muaz, K.; Coppa, C.F.S.C.; Rosim, R.E.; Kamimura, E.S.; Oliveira, C.A.F.; Corassin, C.H. Aflatoxin M1 Absorption by Non-Viable Cells of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Strains in Frescal Cheese. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem-Bekhit, M.M.; Riad, O.K.M.; Selim, H.M.R.M.; Tohamy, S.T.K.; Taha, E.I.; Al-Suwayeh, S.A.; Shazly, G.A. Box–Behnken Design for Assessing the Efficiency of Aflatoxin M1 Detoxification in Milk Using Lactobacillus Rhamnosus and Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Life 2023, 13, 1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanna, P.H.P.; Grandison, A.S.; Charalampopoulos, D. Bifidobacteria in Milk Products: An Overview of Physiological and Biochemical Properties, Exopolysaccharide Production, Selection Criteria of Milk Products and Health Benefits. Food Res. Int. 2014, 55, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A. Aflatoxin Removal and Biotransformation Aptitude of Food Grade Bacteria from Milk and Milk Products- at a Glance. Toxicon 2024, 249, 108084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanaldi, K.; Coban, A.Y. Detoxification of Aflatoxin M1 in Different Milk Types Using Probiotics. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2023, 95, e20220794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, M.T.; El-Shenawy, M.; El-Desouky, T.A. Efficiency of Selected Lactic Acid Bacteria Isolated from Some Dairy Products on Aflatoxin B1 and Ochratoxin A. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 15, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adácsi, C.; Kovács, S.; Pusztahelyi, T. Aflatoxin M1 Binding by Probiotic Bacterial Cells and Cell Fractions. Acta Aliment. 2023, 52, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, N.; Fazeli, M.R.; Sepahi, A.A.; Shariatmadari, F. A New Probiotic Lactobacillus Plantarum Strain Isolated from Traditional Dairy Together with Nanochitosan Particles Shows the Synergistic Effect on Aflatoxin B1 Detoxification. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasiri Poroj, S.; Larypoor, M.; Fazeli, M.R.; Shariatmadari, F. The Synergistic Effect of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles and Yeast Isolated from Fermented Foods in Reduction of Aflatoxin B1. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 7109–7119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mamari, A.; Al-Sadi, A.M.; Al-Harrasi, M.M.A.; Sathish Babu, S.P.; Al-Mahmooli, I.H.; Velazhahan, R. Biodegradation of Aflatoxin B1 by Bacillus Subtilis YGT1 Isolated from Yoghurt. Int. Food Res. J. 2023, 30, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, C.; Ma, Q.; Ji, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, L. Efficacy of Bacillus Subtilis ANSB060 Biodegradation Product for the Reduction of the Milk Aflatoxin M1 Content of Dairy Cows Exposed to Aflatoxin B1. Toxins 2019, 11, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-desouky, T.A.; Kholif, A.M.M. Degradation of Aflatoxin M1 by Lipase and Protease in Buffer Solution and Yoghurt. Open Biotechnol. J. 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Mehta, A. The Main Aflatoxin B1 Degrading Enzyme in Pseudomonas Putida Is Thermostable Lipase. SSRN J. 2022, 8, e10809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, F.; Chitrakar, B.; Wei, G.; Wang, X.; Sang, Y. Three Recombinant Peroxidases as a Degradation Agent of Aflatoxin M1 Applied in Milk and Beer. Food Res. Int. 2023, 166, 112352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezagholizade-shirvan, A.; Ghasemi, A.; Mazaheri, Y.; Shokri, S.; Fallahizadeh, S.; Alizadeh Sani, M.; Mohtashami, M.; Mahmoudzadeh, M.; Sarafraz, M.; Darroudi, M.; et al. Removal of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk Using Magnetic Laccase/MoS2/Chitosan Nanocomposite as an Efficient Sorbent. Chemosphere 2024, 365, 143334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerstner, F.; Cerqueira, M.B.R.; Treichel, H.; Santos, L.O.; Garda Buffon, J. Strategies for Aflatoxins B1 and M1 Degradation in Milk: Enhancing Peroxidase Activity by Physical Treatments. Food Control 2024, 166, 110750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Lv, H.; Rao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Tang, Y.; Zhao, L. Enzymatic Oxidation of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk Using CotA Laccase. Foods 2024, 13, 3702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; You, J.; Li, X.; Xu, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, L. Polysaccharides: A Natural Solution for Mycotoxin Mitigation and Removal. Food Chem. 2025, 496, 146909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girolami, F.; Barbarossa, A.; Badino, P.; Ghadiri, S.; Cavallini, D.; Zaghini, A.; Nebbia, C. Effects of Turmeric Powder on Aflatoxin M1 and Aflatoxicol Excretion in Milk from Dairy Cows Exposed to Aflatoxin B1 at the EU Maximum Tolerable Levels. Toxins 2022, 14, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, F.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, K.; Pei, H.; Tao, F. The Efficacy of Composite Essential Oils against Aflatoxigenic Fungus Aspergillus Flavus in Maize. Toxins 2020, 12, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwad, M.M.A.; El-Sayed, A.S.A.; Abdel-Fattah, G.M.; Abdelmoteleb, M.; Abdel-Fattah, G.G. Potential Fungicidal and Antiaflatoxigenic Effects of Cinnamon Essential Oils on Aspergillus Flavus Inhabiting the Stored Wheat Grains. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Pérez, C.; Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa; Roldán-Hernández, L.; Cruz-Guerrero, A.; Alatorre-Santamaría, S. Evaluation of the Aflatoxin M1 Retention Capacity in a Polysaccharide Obtained by Fermenting Milk with Kefir Grains. Rev. Mex. Ing. Química 2024, 23, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.-Y.; Luo, Z.-Q.; Wang, J.; Peng, T.; Li, Y.; Wei, Z.-Y.; Zhang, Z.-W.; Zou, T. Preparation of Chitin-Derived Hierarchical Porous Materials and Their Application and Mechanism in Adsorption of Mycotoxins. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 291, 139139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elhamed, E.Y.; El-Bassiony, T.A.E.-R.; Elsherif, W.M.; Shaker, E.M. Enhancing Ras Cheese Safety: Antifungal Effects of Nisin and Its Nanoparticles against Aspergillus Flavus. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, K.D.M.; Sibaja, K.V.M.; Feltrin, A.C.P.; Remedi, R.D.; De Oliveira Garcia, S.; Garda-Buffon, J. Occurrence of Aflatoxins B1 and M1 in Milk Powder and UHT Consumed in the City of Assomada (Cape Verde Islands) and Southern Brazil. Food Control 2018, 93, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harshitha, C.G.; Singh, R.; Sharma, R.; Gandhi, K. Fate of Aflatoxin M1 in Milk during Various Processing Treatments. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2024, 77, 1250–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massarolo, K.; Bortoli, K.; De Paula, L.; Kupski, L.; Furlong, E.; Drunkler, D. Distribution and Stability of Aflatoxin M1 in the Processing of Fine Cheeses. SSRN 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebib, H.; Abate, D.; Woldegiorgis, A.Z. Aflatoxin M1 in Raw Milk, Pasteurized Milk and Cottage Cheese Collected along Value Chain Actors from Three Regions of Ethiopia. Toxins 2022, 14, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alahlah, N.; El Maadoudi, M.; Bouchriti, N.; Triqui, R.; Bougtaib, H. Aflatoxin M1 in UHT and Powder Milk Marketed in the Northern Area of Morocco. Food Control 2020, 114, 107262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecorelli, I.; Branciari, R.; Roila, R.; Bibi, R.; Ranucci, D.; Onofri, A.; Valiani, A. Evaluation of Aflatoxin M1 Enrichment Factor in Semihard Cow’s Milk Cheese and Correlation with Cheese Yield. J. Food Prot. 2019, 82, 1176–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarmast, E.; Fallah, A.A.; Jafari, T.; Mousavi Khaneghah, A. Impacts of Unit Operation of Cheese Manufacturing on the Aflatoxin M1 Level: A Global Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. LWT 2021, 148, 111772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamadin, M.; Rama, A.; Seboussi, R. Aflatoxin M1 in Ultra High Temperature Milk Consumed in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates. J. Food Qual. Hazards Control 2022, 9, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatelli, S.; Gambi, L.; Baiguera, C.; Paterlini, F.; Lelli Mami, F.; Uboldi, L.; Daminelli, P.; Biancardi, A. Assessment of Aflatoxin M1 Enrichment Factor in Cheese Produced with Naturally Contaminated Milk. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2023, 12, 11123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costamagna, D.; Gaggiotti, M.; Chiericatti, C.A.; Costabel, L.; Audero, G.M.L.; Taverna, M.; Signorini, M.L. Quantification of Aflatoxin M1 Carry-over Rate from Feed to Soft Cheese. Toxicol. Rep. 2019, 6, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einolghozati, M.; Heshmati, A.; Mehri, F. The Behavior of Aflatoxin M1 during Lactic Cheese Production and Storage. Toxin Rev. 2022, 41, 1163–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahoun, A.; Ahmed, M.; Abou Elez, R.; AbdEllatif, S. Aflatoxin M1 in Milk and Some Dairy Products: Level, Effect of Manufature and Public Health Concerns. Zagazig Vet. J. 2017, 45, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motawee, M.M.; McMahon, D.J. Fate of Aflatoxin M1 during Manufacture and Storage of Feta Cheese. J. Food Sci. 2009, 74, T42–T45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daou, R.; Karam, L.; Antoun, R.; Obeid, S.; Dahboul, T.; El Khoury, A. From Cow’s Milk to Cheese, Yogurt, and Labneh: Evaluating Aflatoxin M1 Fate in Traditional Lebanese Dairy Processing and the Efficacy of Regulations through a Risk Assessment Approach. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2025, 42, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, L.; Paimard, G.; Sadeghi, E.; Rouhi, M.; Mohammadi, R.; Noroozi, R.; Safajoo, S. Fate of Aflatoxins M1 and B1 within the Period of Production and Storage of Tarkhineh: A Traditional Persian Fermented Food. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 945–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayed, A.; Elsayed, H.; Ali, T. Packaging Fortified with Natamycin Nanoparticles for Hindering the Growth of Toxigenic Aspergillus Flavus and Aflatoxin Production in Romy Cheese. J. Adv. Vet. Anim. Res. 2021, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Ma, J.; Li, J.; Yan, L. Study on the Interaction between Aflatoxin M1 and DNA and Its Application in the Removal of Aflatoxin M1. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 355, 118938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanpour, M.; Rezaie, M.R.; Baghizadeh, A. Practical Analysis of Aflatoxin M1 Reduction in Pasteurized Milk Using Low Dose Gamma Irradiation. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 2019, 17, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Palmer, J.; Phan, N.; Shi, H.; Keener, K.; Flint, S. Control of Aflatoxin M1 in Skim Milk by High Voltage Atmospheric Cold Plasma. Food Chem. 2022, 386, 132814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurup, A.H.; Patras, A.; Pendyala, B.; Vergne, M.J.; Bansode, R.R. Evaluation of Ultraviolet-Light (UV-A) Emitting Diodes Technology on the Reduction of Spiked Aflatoxin B1 and Aflatoxin M1 in Whole Milk. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 2022, 15, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Falcón, T.A.; Monter-Arciniega, A.; Cruz-Cansino, N.D.S.; Alanís-García, E.; Rodríguez-Serrano, G.M.; Castañeda-Ovando, A.; García-Garibay, M.; Ramírez-Moreno, E.; Jaimez-Ordaz, J. Effect of Thermoultrasound on Aflatoxin M1 Levels, Physicochemical and Microbiological Properties of Milk during Storage. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018, 48, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikmaram, N.; Keener, K.M. Degradation of Aflatoxin M1 in Skim and Whole Milk Using High Voltage Atmospheric Cold Plasma (HVACP) and Quality Assessment. Food Res. Int. 2022, 162, 112009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallarés, N.; Sebastià, A.; Martínez-Lucas, V.; González-Angulo, M.; Barba, F.J.; Berrada, H.; Ferrer, E. High Pressure Processing Impact on Alternariol and Aflatoxins of Grape Juice and Fruit Juice-Milk Based Beverages. Molecules 2021, 26, 3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ranking | Country | Number of Publication | Percentage (% of 804) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Iran | 137 | 17 |

| 2 | China | 89 | 11 |

| 3 | Brazil | 66 | 8.2 |

| 4 | United States | 54 | 6.7 |

| 5 | Egypt | 53 | 6.6 |

| 6 | Pakistan | 50 | 6.2 |

| 7 | Italy | 46 | 5.7 |

| 8 | India | 41 | 5 |

| 9 | Turkey | 41 | 5 |

| 10 | Spain | 36 | 4.5 |

| 11 | Serbia | 28 | 3.5 |

| 12 | Ethiopia | 21 | 2.6 |

| 13 | Saudi Arabia | 21 | 2.6 |

| 14 | Germany | 19 | 2.4 |

| 15 | Kenya | 19 | 2.4 |

| 16 | Belgium | 14 | 1.7 |

| 17 | Greece | 13 | 1.6 |

| 18 | Mexico | 13 | 1.6 |

| 19 | Sweden | 13 | 1.6 |

| 20 | United Kingdom | 13 | 1.6 |

| Affiliation | Countries | Articles | Percentage of Articles out of 804 |

|---|---|---|---|

| University of Sγo Paulo | Brazil | 71 | 8.8 |

| Islamic Azad University | Iran | 69 | 8.6 |

| Bahauddin Zakariya University | Pakistan | 65 | 8.4 |

| Institute of Animal Science | China | 55 | 6.8 |

| Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences | Iran | 51 | 6.3 |

| University of Novi sad | Serbia | 44 | 5.5 |

| Croatian Veterinary Institute | Croatia | 42 | 5.2 |

| Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences | Iran | 41 | 5.1 |

| University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences | Pakistan | 33 | 4.1 |

| Nanchang University | China | 32 | 4 |

| Ranking | Journal | Number of Publication | Impact Factor (IF) (2024) | Citescore (2024) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Food Control | 76 (9.4%) | 6.3 | 14.1 |

| 2 | Toxins | 55 (6.8%) | 4.0 | 8.2 |

| 3 | Food Chemistry | 30 (3.7%) | 9.8 | 18.3 |

| 4 | Mycotoxin Research | 20 (2.5%) | 3.1 | 4.3 |

| 5 | Journal of Dairy Science | 17 (2.1%) | 4.4 | 7.8 |

| 6 | Food Additives and Contaminants: Part B—Surveillance | 16 (2%) | 2.5 | 5.2 |

| 7 | International Journal of Dairy Technology | 16 (2%) | 2.8 | 5.5 |

| 8 | World Mycotoxin Journal | 11 (1.4%) | 2.2 | 4.8 |

| 9 | Journal of Food Composition and Analysis | 10 (1.2%) | 4.6 | 7.2 |

| 10 | Journal of Food Safety | 10 (1.2%) | 1.8 | 4.2 |

| Rank | Reference | Title | Year | Source | Cited by | Document Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ALSHANNAQ et al. [45] | “Occurrence, Toxicity, and Analysis of Major Mycotoxins in Food” | 2017 | Environmental Research and Public Health | 1019 | Review |

| 2 | MARCHESE et al. [46] | “Aflatoxin B1 and M1: Biological Properties and Their Involvement in Cancer Development” | 2018 | Toxins | 461 | Review |

| 3 | EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM) et al. [47] | “Risk Assessment of Aflatoxin in food” | 2020 | EFSA Journal | 391 | Article |

| 4 | HAQUE et al. [48] | “Mycotoxin contamination and control strategy in human, domestic animal and poultry: A review” | 2020 | Microbial Pathogenesis | 323 | Review |

| 5 | MAHATO et al. [21] | “Aflatoxin in Food and Feed: an Overview on Prevalence, Detection and Control Strategies” | 2019 | Frontiers in Microbiology | 311 | Review |

| 6 | ISMAIL et al. [49] | “Aflatoxin in foodstuffs: Occurrence and recent advances in decontamination” | 2018 | Food Research International | 258 | Review |

| 7 | FLORES-FLORES et al. [50] | “Presence of mycotoxins in animal milk: A review” | 2015 | Food Control | 226 | Review |

| 8 | IQBAL et al. [51] | “Aflatoxin M1 in milk and dairy products, occurrence and recent challenges: A review” | 2015 | Trends in Food Science and Technology | 221 | Review |

| 9 | CAMPAGNOLLO et al. [19] | “The occurrence and effect of unit operations for dairy products processing on the fate of aflatoxin M1: A review” | 2016 | Food Control | 214 | Review |

| 10 | BECKER-ALGERI et al. [52] | “Mycotoxins in Bovine Milk and Dairy Products: A Review” | 2016 | Journal of Food Science | 168 | Review |

| Country | Type of Dairy Product | Positive Samples/Total Samples | Concentration of AFM1 (ng/L) | Samples Exceeding EU Limit (%) | Detection Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh | Raw milk | 75/105 (71.4%) | 5.0–198.7 | 23.8% | ELISA | Sumon et al. [122] |

| Pasteurized milk | 15/15 (100%) | 17.2–187.7 | 73.3% | |||

| UHT milk | 15/15 (100%) | 12.2–146.9 | 73.3% | |||

| Yogurt | 5/5 (100%) | 8.3–41.1 | 0% | |||

| Milk powder | 4/5 (80%) | 5.9–7.0 | 0% | |||

| Bangladesh | Raw milk | 35/50 (70%) | 22.79–1489.28 | 97.1% | ELISA | Tarannum et al. [115] |

| Pasteurized milk | 13/25 (52%) | 18.11–672.18 | 46.1% | |||

| UHT milk | 5/25 (20%) | 25.07–48.95 | 0% | |||

| Brazil | Cheese | 28/28 (100%) | 26–132 | 0% | HPLC-FLD | Silva et al. [123] |

| Brazil | Pasteurized and UHT milk | 6/68 (8.8%) | 15–227 | 1.4% | LC-MS/MS | Frey et al. [102] |

| Brazil | UHT | 15/34 (44.11%) | 150–550 | 100% | HPLC-FLD | Conteçotto et al. [124] |

| Powdered milk | 1/10 (10%) | 1020 | 100% | |||

| Infant formula | 1/16 (6.2%) | 320 | 100% | |||

| China | Pasteurized milk | 1/294 (0.3%) | 33.4 | 100% | Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC) with C18 solid-phase FLD | Meng et al. [103] |

| UHT | 2/92 (2.2%) | 38.7 36.5 | 100% | |||

| Infant formula | 0/20 (0%) | Not detected (ND) | 0% | |||

| China | Pasteurized milk | 40/93 (43%) | 5–11.3 | 0% | ELISA | Xiong et al. [125] |

| Extended shelf life milk | 44/96 (45.8%) | 5–16.5 | 0% | |||

| Donkey raw milk | 0/70 | - | 0% | |||

| Croatia | Raw milk | 109/5817 (1.9%) | 50.3–1100.0 | 100% | ELISA and UHPLC- FLD MS/MS | Bilandžić et al. [126] |

| Egypt | Raw milk | 80/100 (80%) | BDL-105 | 7% | ELISA | Ibrahim et al. [127] |

| Domiati Cheese | 7/33 (21.2%) | BDL-99 | 18% | |||

| Karish cheese | 33/33 (100%) | BDL-183 | 73% | |||

| Ras cheese | 28/34 (82.3%) | BDL-250 | 50% | |||

| Egypt | Raw milk | 20/20 (100%) | 2940–4560 | 100% | ELISA | Ewida et al. [114] |

| Karish cheese | 20/20 (100%) | 3470–30,460 | 100% | |||

| Mish cheese | 20/20 (100%) | 3770–40,500 | 100% | |||

| Egypt | Raw buffalo milk | 43/56 (76.8%) | 28–1200 | 39.29% | ELISA | Elsayed et al. [43] |

| France | Milk | All simulated milk batches assumed to contain AFM1 | 0.33–37.8 | Less than 5% | - | Chhaya et al. [25] |

| India | Raw milk | 204/300 (68%) | >500 | 100% | Charm ROSA Lateral Flow Test | Kumar et al. [60] |

| India | Raw milk | 19/46 (41.3%) | ND-2913 | 84.2% | HPLC-FLD | Hattimare et al. [104] |

| Pasteurized milk | 6/15 (40%) | ND-1212 | 100% | |||

| UHT milk | 18/52 (34.6%) | ND-1523 | 100% | |||

| Milk powder | 2/10 (20%) | ND-2608 | 100% | |||

| Yogurt | 3/10 (30%) | ND-303 | 100% | |||

| Ghana | Raw cow milk | 67/120 (55.8%) | 60–3520 | 52.5% | HPLC-FLD | Kortei et al. [94] |

| Ghana | Wagashi (Traditional cheese) | 11/18 (61.1%) | 0.00–59.2 ± 2 | 5.56% | HPLC-FLD | Kortei et al. [128] |

| Ghana | Fresh cow milk | 53/56 (94.6%) | 61.8–1606.8 | 100% | HPLC-FLD | Nuhu et al. [105] |

| Greece (Thessaly) | Raw milk (cow, goat, sheep) | 39/396 (10.1%) | 7.94–105 (ELISA Kits) 7.96–75 (HPLC-FL) | Not stated | ELISA and HPLC-FLD | Malissiova et al. [107] |

| Greece | Infant/toddler milk | 31/52 (59.6%) | 2.03–9.38 | 0% | ELISA | Maggira et al. [129] |

| Pasteurized milk | 21/32 (65.6%) | 2.04–17.84 | 0% | |||

| Feta cheese | 7/25 (28%) | 2.10–4.09 | 0% | |||

| Hungary | Raw milk | 191/278 (68.7%) | 5–173 | 9.4% | ELISA | Buzás et al. [130] |

| Processed milk | 155/196 (79.1%) | 5.3–100 | 0.5% | ELISA | ||

| Iran (Tabriz) | Raw milk | 8/8 (100%) | 28.30–46.60 | 0% | HPLC-FLD | Behtarin & Movassaghghazani, [32] |

| Pasteurized milk | 8/8 (100%) | 19.50–36.60 | 0% | |||

| UHT milk | 8/8 (100%) | 16.10–36.10 | 0% | |||

| Traditional yogurt | 8/8 (100%) | 35.30–50.20 | 25% | |||

| Pasteurized yogurt | 8/8 (100%) | 21.60–41.70 | 0% | |||

| Traditional cheese | 8/8 (100%) | 45.50–105.70 | 0% | |||

| Pasteurized cheese | 8/8 (100%) | 31.80–55.40 | 12.5% | |||

| Iran (Ilam and Lorestan Provinces) | Raw Milk | 40/40 (100%) | 38.6–85.0 | 46.6% | HPLC-FLD | Aghebatbinyeganeh et al. [131] |

| Pasteurized milk | 40/40 (100%) | 24.1–59.7 | ||||

| UHT milk | 40/40 (100%) | 21.4–69.4 | ||||

| Traditional cheese | 40/40 (100%) | 80.4–169.4 | 100% | |||

| Pasteurized cheese | 40/40 (100%) | 28.4–67.5 | 0% | |||

| Traditional Yogurt | 40/40 (100%) | 55.2–99.1 | 100% | |||

| Iran (Tehran) | Powdered milk | 24/25 (96%) | 0.00–95.5 | 68% | HPLC-FLD | Movassaghghazani & Shabansalmani [91] |

| Iran (Golestan Province) | Camel milk | 10/10 (100%) | 57.10 | 57.5% | HPLC-FLD | Jorjani & Movassaghghazani [132] |

| Raw milk | 10/10 (100%) | 72.81 | ||||

| Pasteurized milk | 10/10 (100%) | 34.73 | ||||

| UHT milk | 10/10 (100%) | 49.36 | ||||

| Ireland | Milk | All simulated milk batches assumed to contain AFM1 | 0.00087–5.72 | Around 1% | Chhaya et al. [25] | |

| Italy (Sicily area) | Cow milk | 0/180 (0%) | Below LOD | 0% | HPLC-FLD | Messina et al. [13] |

| Italy (northern Italy) | Raw cow milk | At least 1057 | <5 ng/L to >80 ng/L | 0.7% | ELISA and HPLC-FLD | Ferrari et al. [133] |

| Italy | Cow milk | 2244/3151 (71.2%) | 9–146 | 0.9% | ELISA and HPLC-FLD | Roila et al. [119] |

| Ewe milk | 1424/5254 (27.1%) | 6–239 | 1.1% | |||

| Cheesemaking cow’s milk | 5817/8529 (68.2%) | 6–208 | 2.2% | |||

| Kenya | Raw milk | 13/190 (6.84%) | >200 ng/L (None above 350 ng/L) | Not mentioned | Commercial lateral flow assay (LFA) | Smith et al. [134] |

| Kenya | Raw milk | Not stated/512 | Mean value: Sub-Humid: 370.7 (n = 2), Humid: 52.9, Temperate: 34.6, Semi-Arid: 8.3 | 10% | ELISA | Sirma et al. [96] |