Biochemical Quality Profile of Black Tea from Upper Assam and North Bank Region of Assam, India

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Instrumentation

2.3. Tea Sampling and Sample Preparation for Analysis

2.4. Determination of Dry Matter Content

2.5. Determination of Total Polyphenol Content

2.6. Determination of Catechin and Caffeine Content

2.7. Determination of Theanine Content

2.8. Determination of Water Extract

2.9. Determination of Crude Fibre

2.10. Determination of Thearubigin Content

2.11. Determination of Theaflavin Profile

2.12. Determination of Total Ash and Its Profile

2.12.1. Determination of Total Ash

2.12.2. Determination of Water-Insoluble and Water-Soluble Ash

2.12.3. Determination of Acid-Insoluble Ash

2.12.4. Determination of Alkalinity of Water-Soluble Ash

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Total Polyphenol

3.2. Water Extract

3.3. Caffeine

3.4. Crude Fibre

3.5. Thearubigin

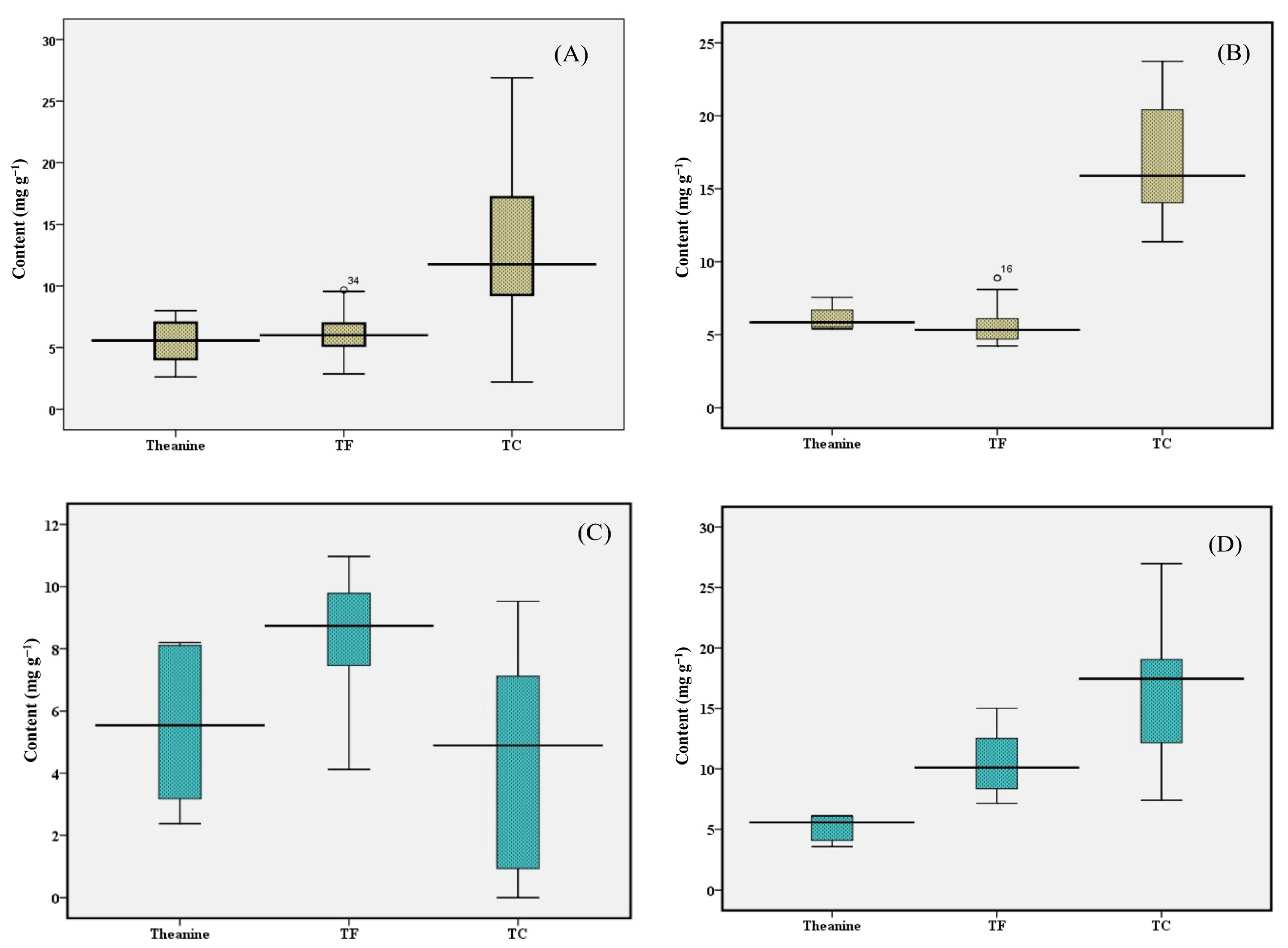

3.6. Theanine

3.7. Theaflavin Profile

3.8. Ash Profile

3.9. Correlation Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sarmah, P.P.; Deka, H.; Sabhapondit, S.; Chowdhury, P.; Rajkhowa, K.; Karak, T. Black Tea: Manufacturing And. In Tea in Health and Disease Prevention, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Qiao, F.; Huang, J. Black Tea Markets Worldwide: Are They Integrated? J. Integr. Agric. 2022, 21, 552–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deka, H.; Sarmah, P.P.; Nath, B.; Gogoi, M.; Datta, S.; Sabhapondit, S. Unveiling the Effect of Leaf Maturity on Biochemical Constituents and Quality of CTC Black Tea: Insights from Northeast India’s Commercial Cultivars. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2024, 18, 9921–9937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.; Wang, Z.; Peng, H.; Li, W.; Yang, P. UPLC–QTOF/MS-Based Non-Targeted Metabolomics Coupled with the Quality Component, QDA, to Reveal the Taste and Metabolite Characteristics of Six Types of Congou Black Tea. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 185, 115197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 3720:2011; ISO Black Tea-Definition and Basic Requirements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- Tea Board. State Wise/Region Wise and Month Wise Tea Production Data; Tea Board: Kolkata, India, 2025.

- Bhuyan, L.P.; Sabhapondit, S.; Baruah, B.D.; Bordoloi, C.; Gogoi, R.; Bhattacharyya, P. Polyphenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of CTC Black Tea of North-East India. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 3744–3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deka, H.; Barman, T.; Dutta, J.; Devi, A.; Tamuly, P.; Kumar Paul, R.; Karak, T. Catechin and Caffeine Content of Tea (Camellia sinensis L.) Leaf Significantly Differ with Seasonal Variation: A Study on Popular Cultivars in North East India. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2021, 96, 103684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, L.P.; Hussain, A.; Tamuly, P.; Gogoi, R.C.; Bordoloi, P.K.; Hazarika, M. Chemical Characterisation of CTC Black Tea of Northeast India: Correlation of Quality Parameters with Tea Tasters’ Evaluation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2009, 89, 1498–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, M.; Fang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Ruan, J. Accumulation of Amino Acids and Flavonoids in Young Tea Shoots Is Highly Correlated with Carbon and Nitrogen Metabolism in Roots and Mature Leaves. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 756433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deka, H.; Sarmah, P.P.; Devi, A.; Tamuly, P.; Karak, T. Changes in Major Catechins, Caffeine, and Antioxidant Activity during CTC Processing of Black Tea from North East India. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 11457–11467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14502-1:2005; ISO Determination of Substances Characteristic of Green and Black Tea—Part 1: Content of Total Polyphenols in Tea—Colorimetric Method Using Folin-Ciocalteu Reagent. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- ISO 14502-2:2005; ISO Determination of Substances Characteristic of Green and Black Tea—Part 2: Content of Catechins in Green Tea—Method Using High-Performance Chromatography. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- ISO 19563:2017; ISO Determination of Theanine in Tea and Instant Tea in Solid Form Using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Deka, H.; Sarmah, P.P.; Chowdhury, P.; Gogoi, M.; Patel, P.K.; Gogoi, R.C. Effect of CTC Processing on Quality Characteristics of Green Tea Infusion: A Comparative Study with Conventional Orthodox Processing. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 94, 103694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 15598:1999; ISO Tea-Determination of Crude Fibre Content. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999.

- Ullah, M.R. A Rapid Procedure for Estimating Theaflavins and Thearubigins of Black Tea. Two A Bud 1986, 33, 46–48. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 18447:2021; ISO Determination of Theaflavins in Black Tea—Method Using High Performance Liquid Chromatography. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- ISO 1575:1987; ISO Tea—Determination of Total Ash. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1987.

- ISO 1576:1988; ISO Tea—Determination of Water—Soluble Ash and Water—Insoluble Ash. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1988.

- ISO 1577:1987; ISO Tea—Determination of Acid—Insoluble Ash. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1987.

- ISO 1578:1975; ISO Tea—Determination of Alkalinity of Water-Soluble Ash. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1975.

- Deka, H.; Sarmah, P.P.; Chowdhury, P.; Rajkhowa, K.; Sabhapondit, S.; Panja, S.; Karak, T. Impact of the Season on Total Polyphenol and Antioxidant Properties of Tea Cultivars of Industrial Importance in Northeast India. Foods 2023, 12, 3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food Safety and Standards Authority of India. Food Safety and Standards (Food Products Standards and Food Additives) Regulations; Food Safety and Standards Authority of India: New Delhi, India, 2011.

- Roberts, E.A.H. The Chemistry of Tea Manufacture. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1958, 9, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kc, Y.; Parajuli, A.; Khatri, B.B.; Shiwakoti, L.D. Phytochemicals and Quality of Green and Black Teas from Different Clones of Tea Plant. J. Food Qual. 2020, 2020, 8874271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Yu, Q.; Shen, S.; Shan, X.; Hua, J.; Zhu, J.; Qiu, J.; Deng, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Non-Targeted Metabolomics and Electronic Tongue Analysis Reveal the Effect of Rolling Time on the Sensory Quality and Nonvolatile Metabolites of Congou Black Tea. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 169, 113971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, C.; Özdemir, F.; Gökmen, V. Investigation of Free Amino Acids, Bioactive and Neuroactive Compounds in Different Types of Tea and Effect of Black Tea Processing. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 117, 108655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, S.B.; Ullah, M.R. The Evaluation of Black Teas. Two A Bud 1968, 15, 101–102. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, J.; Xu, Q.; Yuan, H.; Wang, J.; Wu, Z.; Li, X.; Jiang, Y. Effects of Novel Fermentation Method on the Biochemical Components Change and Quality Formation of Congou Black Tea. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2021, 96, 103751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, S.H.; Yang, K.M.; Wang, S.Y.; Chen, C.W. Enzymatic Treatment in Black Tea Manufacturing Processing: Impact on Bioactive Compounds, Quality, and Bioactivities of Black Tea. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 163, 113560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, S.; Alam, S.; Saleem, M.; Ahmad, W.; Bibi, R.; Hamid, F.S.; Shah, H.U. Withering Timings Affect the Total Free Amino Acids and Mineral Contents of Tea Leaves during Black Tea Manufacturing. Arab. J. Chem. 2019, 12, 2411–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Yang, M.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, C. Changes of Physiological Characteristics, Element Accumulation and Hormone Metabolism of Tea Leaves in Response to Soil pH. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1266026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| (a) | |||||||

| Sample | Types | TP (mg g−1) | WE (mg g−1) | Caffeine (mg g−1) | CF (mg g−1) | TR (mg g−1) | Theanine (mg g−1) |

| U1 | Orthodox | 107.74 ± 3.27 ij | 399.14 ± 2.23 d | 25.18 ± 1.89 fg | 119.54 ± 1.08 de | 139.67 ± 5.72 abc | 5.46 ± 0.17 cd |

| U2 | Orthodox | 100.29 ± 0.28 jk | 373.02 ± 1.25 fg | 24.73 ± 3.44 fg | 118.16 ± 8.88 def | 115.10 ± 0.43 efg | 5.60 ± 0.04 c |

| U3 | CTC | 97.39 ± 1.18 k | 380.97 ± 4.68 ef | 21.73 ± 6.22 gh | 150.16 ± 6.47 bc | 114.98 ± 3.30 efg | 3.99 ± 0.12 e |

| U4 | CTC | 83.54 ± 1.68 l | 360.57 ± 4.57 h | 16.82 ± 1.32 i | 162.71 ± 2.08 a | 121.09 ± 11.64 def | 2.47 ± 0.08 h |

| U5 | Orthodox | 143.22 ± 7.14 cd | 410.85 ± 6.74 c | 15.51 ± 1.07 i | 106.75 ± 4.75 ghi | 90.08 ± 7.05 hi | 3.91 ± 0.31 e |

| U6 | Orthodox | 143.47 ± 3.27 cd | 423.81 ± 4.20 b | 17.98 ± 1.63 hi | 102.25 ± 0.41 hi | 101.06 ± 13.02 gh | 3.59 ± 0.22 ef |

| U7 | Orthodox | 136.57 ± 5.31 de | 402.78 ± 1.71 cd | 30.60 ± 1.46 bcd | 116.96 ± 3.97 defg | 97.76 ± 6.15 gh | 2.76 ± 0.16 gh |

| U8 | Orthodox | 148.56 ± 0.66 c | 431.29 ± 4.37 b | 33.54 ± 1.30 ab | 111.05 ± 2.26 efgh | 140.92 ± 16.25 ab | 2.86 ± 0.01 gh |

| U9 | Orthodox | 120.50 ± 0.74 fgh | 380.25 ± 6.27 ef | 33.09 ± 0.39 abc | 124.28 ± 2.34 d | 123.40 ± 5.25 bcdef | 7.06 ± 0.04 b |

| U10 | Orthodox | 121.10 ± 2.13 fg | 367.78 ± 2.61 gh | 33.14 ± 0.10 abc | 157.50 ± 7.33 ab | 73.95 ± 12.14 i | 7.27 ± 0.18 b |

| U11 | Orthodox | 115.48 ± 0.95 ghi | 373.68 ± 3.16 fg | 33.41 ± 0.33 ab | 114.46 ± 4.67 defg | 111.22 ± 7.56 fg | 7.00 ± 0.15 b |

| U12 | Orthodox | 128.17 ± 1.94 ef | 399.17 ± 6.25 d | 36.21 ± 0.32 a | 121.30 ± 7.64 de | 136.35 ± 13.62 abcd | 5.69 ± 0.05 c |

| U13 | Orthodox | 166.46 ± 4.56 b | 445.80 ± 1.56 a | 35.57 ± 0.57 a | 97.33 ± 1.90 i | 122.21 ± 12.89 cdef | 7.18 ± 0.71 b |

| U14 | Orthodox | 184.52 ± 3.91 a | 430.77 ± 3.34 b | 36.88 ± 0.41 a | 101.20 ± 1.78 hi | 90.73 ± 5.60 hi | 7.31 ± 0.44 b |

| U15 | CTC | 108.57 ± 9.49 ij | 375.05 ± 4.41 efg | 28.17 ± 1.93 def | 157.21 ± 4.22 ab | 145.37 ± 6.22 a | 3.18 ± 0.08 fg |

| U16 | CTC | 102.93 ± 6.08 jk | 376.36 ± 2.91 efg | 25.80 ± 1.12 efg | 145.99 ± 1.54 c | 141.74 ± 6.62 a | 7.23 ± 0.43 b |

| U17 | Orthodox | 111.99 ± 2.92 hi | 380.09 ± 4.80 ef | 32.98 ± 1.99 abc | 107.59 ± 9.74 fghi | 140.11 ± 7.62 abc | 5.00 ± 0.17 d |

| U18 | Orthodox | 108.03 ± 4.76 ij | 349.29 ± 9.07 i | 28.90 ± 0.99 cdef | 150.67 ± 4.76 bc | 86.09 ± 2.43 hi | 5.24 ± 0.14 cd |

| U19 | CTC | 118.24 ± 2.59 gh | 383.99 ± 2.65 e | 27.98 ± 0.18 def | 155.15 ± 6.50 abc | 112.68 ± 2.66 fg | 8.16 ± 0.03 a |

| U20 | CTC | 115.28 ± 1.25 ghi | 384.06 ± 1.73 e | 29.80 ± 0.14 bcde | 154.77 ± 3.93 abc | 132.29 ± 5.08 abcde | 8.07 ± 0.09 a |

| (b) | |||||||

| Sample | Types | TP (mg g−1) | WE (mg g−1) | Caffeine (mg g−1) | CF (mg g−1) | TR (mg g−1) | Theanine (mg g−1) |

| N1 | Orthodox | 152.91 ± 10.64 cd | 406.58 ± 8.61 c | 37.40 ± 1.89 ab | 91.87 ± 3.84 e | 116.44 ± 3.13 bc | 6.69 ± 0.06 b |

| N2 | Orthodox | 148.97 ± 1.28 cd | 411.71 ± 1.83 bc | 35.74 ± 1.28 bc | 93.95 ± 2.43 e | 115.70 ± 4.65 bc | 5.61 ± 0.02 e |

| N3 | Orthodox | 139.28 ± 3.23 de | 406.76 ± 3.69 c | 30.75 ± 0.50 efgh | 127.07 ± 5.00 bc | 59.62 ± 4.73 f | 6.22 ± 0.19 c |

| N4 | Orthodox | 148.09 ± 2.56 cd | 431.08 ± 4.73 a | 32.94 ± 1.13 cdef | 118.88 ± 3.10 c | 87.09 ± 5.64 e | 7.49 ± 0.07 a |

| N5 | Orthodox | 131.67 ± 4.84 e | 428.92 ± 13.33 ab | 31.43 ± 1.19 defg | 118.69 ± 2.14 c | 127.91 ± 7.01 ab | 5.43 ± 0.07 e |

| N6 | CTC | 151.04 ± 9.48 cd | 440.50 ± 7.49 a | 29.86 ± 1.42 fgh | 139.19 ± 4.49 a | 118.23 ± 10.27 bc | 6.09 ± 0.06 cd |

| N7 | CTC | 140.77 ± 2.79 de | 434.64 ± 5.36 a | 28.10 ± 0.54 h | 140.77 ± 7.55 c | 137.84 ± 11.86 a | 6.01 ± 0.11 d |

| N8 | CTC | 150.66 ± 7.49 cd | 442.51 ± 12.36 a | 28.68 ± 1.74 gh | 130.80 ± 2.12 ab | 127.19 ± 10.31 ab | 3.61 ± 0.04 h |

| N9 | Orthodox | 180.85 ± 7.15 a | 434.03 ± 10.92 a | 39.24 ± 1.49 a | 104.76 ± 2.95 d | 113.61 ± 1.66 bc | 5.53 ± 0.15 e |

| N10 | CTC | 154.01 ± 8.21 cd | 436.77 ± 12.25 a | 33.23 ± 0.92 cde | 129.51 ± 7.13 ab | 119.50 ± 3.16 bc | 5.17 ± 0.08 f |

| N11 | CTC | 160.23 ± 9.18 bc | 432.02 ± 14.87 a | 33.26 ± 2.33 cde | 117.63 ± 1.31 c | 108.09 ± 4.29 cd | 6.08 ± 0.04 cd |

| N12 | CTC | 169.74 ± 3.10 ab | 447.54 ± 9.85 a | 34.29 ± 0.66 bcd | 117.39 ± 3.61 c | 95.71 ± 3.40 de | 4.09 ± 0.09 g |

| (a) | ||||||

| Sample | Types | Water Insoluble (%) | Water Soluble (%) | Total (%) | Acid Insoluble (%) | Alkalinity of Water Soluble Ash (g KOH Equivalent) |

| U1 | Orthodox | 3.97 ± 0.31 a | 4.45 ± 0.15 ab | 8.42 ± 0.45 a | 1.98 ± 0.35 a | 2.05 ± 0.05 def |

| U2 | Orthodox | 2.62 ± 0.87 b | 3.87 ± 0.78 b | 6.49 ± 0.16 cdef | 0.26 ± 0.09 def | 2.02 ± 0.03 efg |

| U3 | CTC | 2.31 ± 0.13 bcd | 4.21 ± 0.17 ab | 6.52 ± 0.30 cdef | 0.05 ± 0.04 f | 2.00 ± 0.21 efg |

| U4 | CTC | 2.21 ± 0.07 bcde | 4.00 ± 0.03 ab | 6.21 ± 0.04 cdefg | 0.19 ± 0.03 ef | 2.13 ± 0.03 bcdef |

| U5 | Orthodox | 2.08 ± 0.25 cde | 4.43 ± 0.54 ab | 6.51 ± 0.76 cdef | 0.18 ± 0.03 f | 2.19 ± 0.24 abcde |

| U6 | Orthodox | 2.34 ± 0.03 bcd | 4.33 ± 0.06 ab | 6.67 ± 0.05 cd | 0.24 ± 0.03 def | 2.32 ± 0.01 ab |

| U7 | Orthodox | 2.22 ± 0.06 bcde | 4.55 ± 0.20 a | 6.76 ± 0.23 c | 0.05 ± 0.01 f | 2.35 ± 0.03 ab |

| U8 | Orthodox | 3.83 ± 0.28 a | 4.23 ± 0.04 ab | 8.06 ± 0.32 ab | 1.50 ± 0.25 b | 2.16 ± 0.03 abcde |

| U9 | Orthodox | 2.06 ± 0.24 cde | 4.52 ± 0.59 a | 6.58 ± 0.83 cde | 0.15 ± 0.02 f | 2.32 ± 0.30 ab |

| U10 | Orthodox | 2.05 ± 0.11 cde | 4.02 ± 0.13 ab | 6.08 ± 0.05 defgh | 0.19 ± 0.11 ef | 2.34 ± 0.08 ab |

| U11 | Orthodox | 1.97 ± 0.09 cde | 3.96 ± 0.05 ab | 5.93 ± 0.05 efgh | 0.19 ± 0.04 ef | 2.14 ± 0.01 bcdef |

| U12 | Orthodox | 3.63 ± 0.35 a | 3.89 ± 0.07 b | 7.52 ± 0.31 b | 1.89 ± 0.34 a | 2.04 ± 0.02 def |

| U13 | Orthodox | 1.91 ± 0.02 de | 4.13 ± 0.07 ab | 6.04 ± 0.07 defgh | 0.14 ± 0.04 f | 2.08 ± 0.01 cdef |

| U14 | Orthodox | 1.83 ± 0.04 de | 3.99 ± 0.04 ab | 5.82 ± 0.07 gh | 0.04 ± 0.01 f | 2.37 ± 0.08 a |

| U15 | CTC | 2.07 ± 0.02 cde | 3.84 ± 0.05 b | 5.91 ± 0.07 fgh | 0.02 ± 0.01 f | 1.92 ± 0.06 fg |

| U16 | CTC | 2.32 ± 0.07 bcd | 4.13 ± 0.01 ab | 6.45 ± 0.05 cdefg | 0.46 ± 0.02 cde | 2.26 ± 0.09 abcd |

| U17 | Orthodox | 1.78 ± 0.01 e | 4.31 ± 0.10 ab | 6.08 ± 0.10 defgh | 0.15 ± 0.01 f | 1.80 ± 0.02 g |

| U18 | Orthodox | 2.32 ± 0.07 bcd | 3.20 ± 0.28 c | 5.53 ± 0.21 h | 0.68 ± 0.10 c | 1.91 ± 0.03 fg |

| U19 | CTC | 2.49 ± 0.02 bc | 3.97 ± 0.18 ab | 6.46 ± 0.19 cdefg | 0.51 ± 0.03 cd | 2.21 ± 0.05 abcde |

| U20 | CTC | 2.35 ± 0.03 bcd | 4.08 ± 0.04 ab | 6.43 ± 0.06 cdefg | 0.51 ± 0.04 cd | 2.28 ± 0.04 abc |

| (b) | ||||||

| Sample | Types | Water Insoluble (%) | Water Soluble (%) | Total (%) | Acid Insoluble (%) | Alkalinity of Water Soluble Ash (g KOH Equivalent) |

| N1 | Orthodox | 1.81 ± 0.12 de | 3.78 ± 0.27 | 5.59 ± 0.21 e | 0.10 ± 0.01 def | 1.89 ± 0.05 f |

| N2 | Orthodox | 1.89 ± 0.02 cde | 3.87 ± 0.11 | 5.76 ± 0.11 cde | 0.12 ± 0.03 cde | 2.15 ± 0.03 abc |

| N3 | Orthodox | 1.98 ± 0.13 bcd | 4.18 ± 0.17 | 6.16 ± 0.23 ab | 0.04 ± 0.01 f | 2.17 ± 0.07 ab |

| N4 | Orthodox | 2.13 ± 0.21 ab | 3.84 ± 0.10 | 5.97 ± 0.11 abcd | 0.04 ± 0.01 f | 2.03 ± 0.05 e |

| N5 | Orthodox | 1.70 ± 0.06 e | 3.96 ± 0.01 | 5.66 ± 0.06 de | 0.05 ± 0.01 f | 2.02 ± 0.04 e |

| N6 | CTC | 2.03 ± 0.10 bc | 4.03 ± 0.33 | 6.05 ± 0.31 abc | 0.05 ± 0.01 ef | 2.03 ± 0.04 de |

| N7 | CTC | 2.13 ± 0.03 ab | 4.12 ± 0.15 | 6.25 ± 0.17 ab | 0.23 ± 0.03 a | 2.25 ± 0.03 a |

| N8 | CTC | 2.25 ± 0.02 a | 4.09 ± 0.14 | 6.34 ± 0.14 a | 0.18 ± 0.03 abc | 2.13 ± 0.07 bcd |

| N9 | Orthodox | 1.88 ± 0.06 cde | 3.88 ± 0.16 | 5.76 ± 0.13 cde | 0.20 ± 0.03 ab | 2.06 ± 0.04 cde |

| N10 | CTC | 2.08 ± 0.09 abc | 3.95 ± 0.09 | 6.03 ± 0.18 abc | 0.15 ± 0.03 bcd | 2.11 ± 0.05 bcde |

| N11 | CTC | 1.72 ± 0.02 e | 3.89 ± 0.01 | 5.62 ± 0.03 de | 0.10 ± 0.07 def | 2.13 ± 0.03 bcd |

| N12 | CTC | 1.91 ± 0.04 cde | 4.00 ± 0.01 | 5.91 ± 0.05 bcde | 0.10 ± 0.02 def | 2.20 ± 0.01 ab |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sarmah, P.P.; Deka, H.; Parasar, P.; Baruah, R.; Sabhapondit, S.; Buragohain, D. Biochemical Quality Profile of Black Tea from Upper Assam and North Bank Region of Assam, India. Foods 2026, 15, 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010158

Sarmah PP, Deka H, Parasar P, Baruah R, Sabhapondit S, Buragohain D. Biochemical Quality Profile of Black Tea from Upper Assam and North Bank Region of Assam, India. Foods. 2026; 15(1):158. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010158

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarmah, Podma Pollov, Himangshu Deka, Priyanuj Parasar, Rashmi Baruah, Santanu Sabhapondit, and Dibyajit Buragohain. 2026. "Biochemical Quality Profile of Black Tea from Upper Assam and North Bank Region of Assam, India" Foods 15, no. 1: 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010158

APA StyleSarmah, P. P., Deka, H., Parasar, P., Baruah, R., Sabhapondit, S., & Buragohain, D. (2026). Biochemical Quality Profile of Black Tea from Upper Assam and North Bank Region of Assam, India. Foods, 15(1), 158. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010158