Detection, Identification, and Diffusion of Yeasts Responsible for Structural Defects in Provolone Valpadana PDO Cheese Using Multiple Research Techniques

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cheese Sampling

| Different Defective Cheese Batches | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample name | Coliforms | Heterofermentative LAB | Leuconostoc spp. | Spore-forming bacteria | Yeasts | Molds | Propionibacteria |

| A | <0.70 | <0.70 | <0.70 | 2.49 ± 0.01 | 3.23 ± 0.05 | <1.70 | <0.70 |

| B | <0.70 | <0.70 | 3.39 ± 0.39 | <1.70 | 4.08 ± 0.03 | <1.70 | <0.70 |

| C | <0.70 | <0.70 | <0.70 | 2.80 ± 0.02 | 3.75 ± 0.15 | <1.70 | <0.70 |

| D | <0.70 | <0.70 | <2.70 | 3.33 ± 0.03 | 3.45 ± 0.15 | 2.27 ± 0.57 | 2.78 ± 0.07 |

| E | <0.70 | <0.70 | <2.70 | 2.63 ± 0.15 | 3.19 ± 0.19 | 2.57 ± 0.57 | <0.70 |

| F | <0.70 | <0.70 | <2.70 | 2.91 ± 0.13 | 4.06 ± 0.02 | <1.70 | <0.70 |

| G | <0.70 | <0.70 | <2.70 | 4.31 ± 0.03 | 3.72 ± 0.12 | <1.70 | <0.70 |

| H | <0.70 | <0.70 | <2.70 | <1.70 | 4.76 ± 0.01 | <1.70 | <0.70 |

| I | <0.70 | <0.70 | <2.70 | <1.70 | 3.77 ± 0.02 | <1.70 | <0.70 |

| On-site inspection of 21 September 2023 | |||||||

| Samples | Coliforms | Heterofermentative LAB | Leuconostoc spp. | Spore-forming bacteria | Yeasts | Molds | Propionibacteria |

| drained whey | 1.2 ± 0.05 | <0.50 | <0.50 | <1.70 | <1.70 | <1.70 | 2.23 ± 0.05 |

| whey starter | <0.50 | <0.50 | <0.50 | <0.70 | <1.70 | <1.70 | <0.50 |

| curd before maturation | <0.70 | <0.70 | <0.70 | <1.70 | 1.98 ± 0.02 | <1.70 | <0.70 |

| curd after maturation | <0.70 | <0.70 | <0.70 | <1.70 | 2.89 ± 0.11 | <1.70 | 1.54 ± 0.06 |

| curd after stretching | <0.70 | <0.70 | <0.70 | <1.70 | 3.40 ± 0.03 | <1.70 | 2.02 ± 0.02 |

| PV cheese 30 days | <0.70 | <0.70 | <1.70 | <0.70 | 4.28 ± 0.01 | <1.70 | <1.70 |

| PV cheese 60 days | <0.70 | <0.70 | <1.70 | <1.70 | 2.30 ± 0.30 | <1.70 | <1.70 |

| PV cheese 90 days | <0.70 | <0.70 | <1.70 | <1.70 | <1.70 | <1.70 | 1.48 ± 0.04 |

| On-site inspection of 6 February 2024 | |||||||

| Samples | Coliforms | Heterofermentative LAB | Leuconostoc spp. | Spore-forming bacteria | Yeasts | Molds | Propionibacteria |

| drained whey | 3.24 ± 0.06 | <0.50 | 1.04 ± 0.04 | <0.50 | 2.74 ± 0.05 | <0.50 | <0.50 |

| whey starter | <0.5 | <0.50 | <0.50 | <0.50 | 2.58 ± 0.04 | <0.50 | <0.50 |

| curd before maturation | 0.92 ± 0.08 | <0.70 | <0.70 | <0.70 | 2.02 ± 0.02 | <0.70 | 1.10 ± 0.20 |

| curd after maturation | <0.70 | <0.70 | <0.70 | <0.70 | 1.78 ± 0.18 | <0.70 | 0.89 ± 0.11 |

| curd after stretching | <0.70 | <0.70 | <0.70 | <0.70 | <0.70 | <0.70 | 0.89 ± 0.11 |

| PV cheese 30 days | <0.70 | <0.70 | <1.70 | <1.70 | 4.81 ± 0.01 | <0.70 | <1.70 |

| PV cheese 60 days | <0.70 | <0.70 | <1.70 | <0.70 | 2.66 ± 0.01 | <0.70 | <0.70 |

| PV cheese 90 days | <0.70 | <0.70 | <1.70 | 1.59 ± 0.11 | 3.27 ± 0.01 | <0.70 | <0.70 |

2.2. Microbiological Analysis

2.3. Yeast Isolation and Purification

2.4. DNA Extraction and Genotyping of the Yeast Isolates

2.5. Isolate Identification

2.6. Metagenomic Analysis

2.7. Chemical Analysis

3. Results

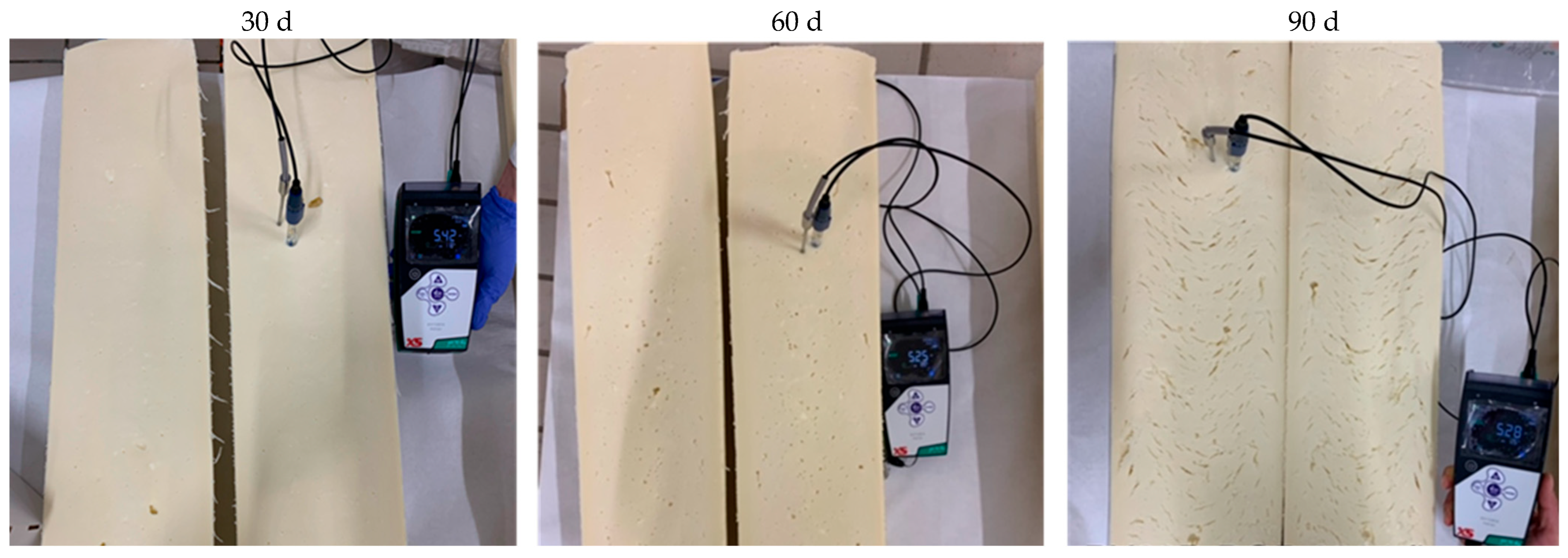

3.1. Description of the Defect

3.2. Microbiological Analysis

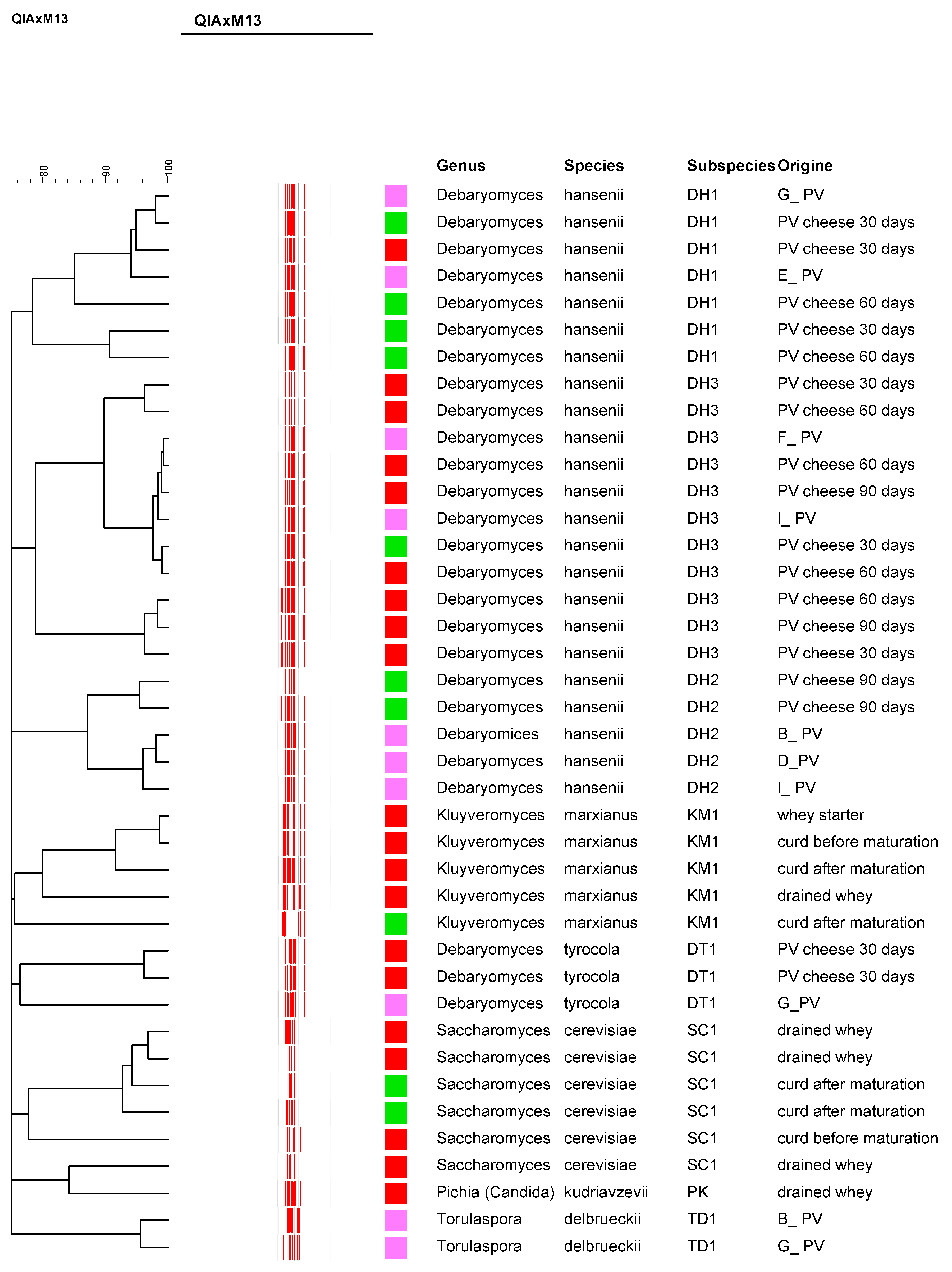

3.3. Yeast Isolation, RAPD Typing, and Molecular Identification

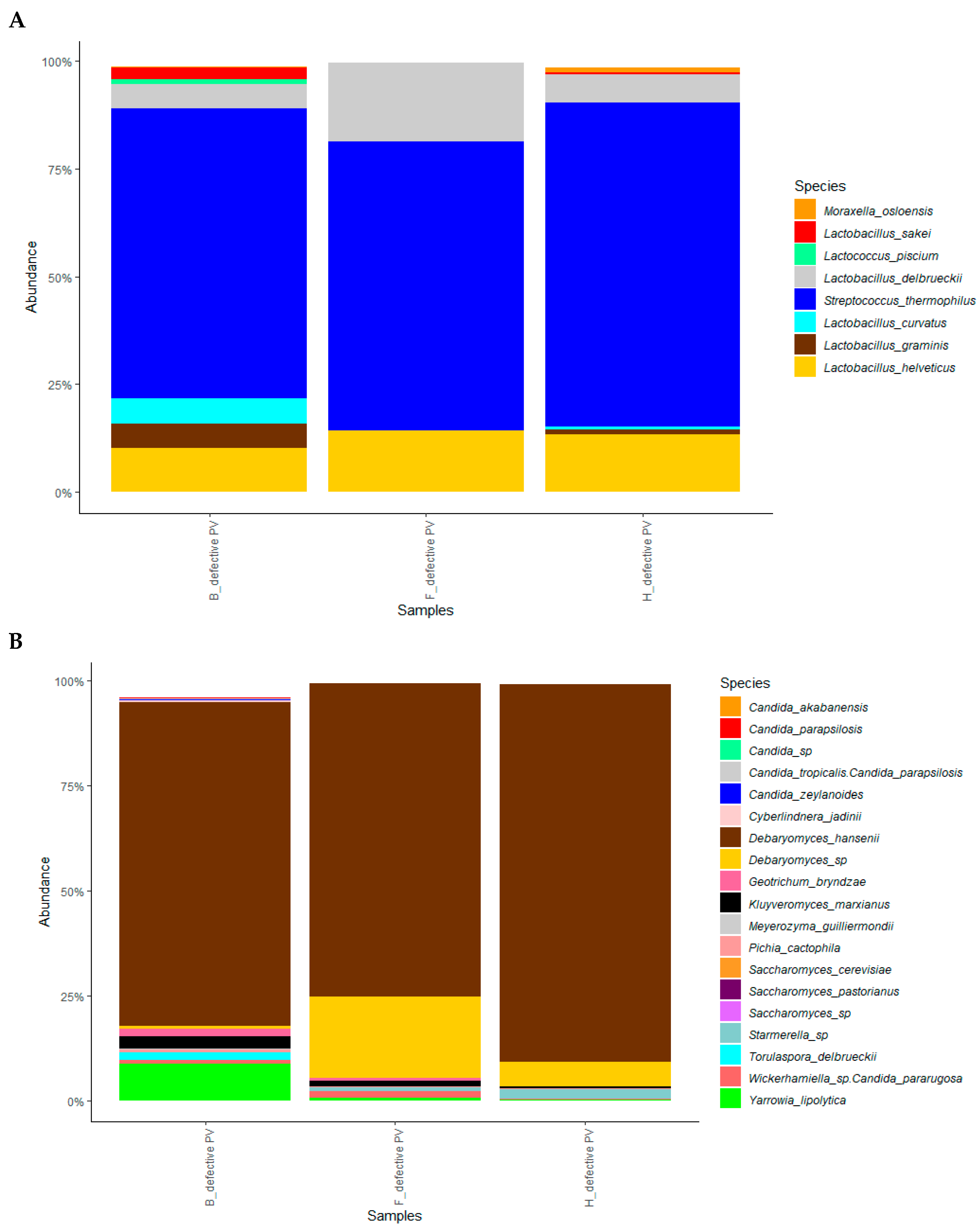

3.4. Metagenomic Analysis

3.5. Chemical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zago, M.; Bonvini, B.; Rossetti, L.; Fergonzi, G.; Tidona, F.; Giraffa, G.; Carminati, D. Raw milk for Provolone Valpadana PDO cheese: Impact of modified cold storage conditions on the composition of the bacterial biota. Dairy 2022, 3, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbetti, M.; Neviani, E.; Fox, P. The Cheeses of Italy: Science and Technology, 1st ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 244–259. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, K.; Lee, H.; Lee, S.; Kim, S.; Yoon, Y. Cheese microbial risk assessments—A Review. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 29, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, P.F.; Cogan, T.M.; Guinee, T.P. Factors that affect the quality of cheese. In Cheese: Chemistry, Physics and Microbiology; McSweeney, P.L.H., Fox, P.F., Everett, D.W., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2017; pp. 617–641. [Google Scholar]

- Pasquali, F.; Valero, A.; Possas, A.; Lucchi, A.; Crippa, C.; Gambi, L.; Manfreda, G.; De Cesare, A. Occurrence of foodborne pathogens in Italian soft artisanal cheeses displaying different intra-and inter-batch variability of physicochemical and microbiological parameters. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 959648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruzy, M.F.; Blaiotta, G.; Aponte, M.; De Sena, M.; Murru, N. Late blowing defect in Grottone cheese: Detection of clostridia and control strategies. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2022, 11, 10162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aponte, M.; Pepe, O.; Blaiotta, G. Short communication: Identification and technological characterization of yeast strains isolated from samples of water buffalo Mozzarella cheese. J. Dairy Sci. 2010, 93, 2358–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, N.H.; Torres-Frenzel, P.; Wiedmann, M. Invited review: Controlling dairy product spoilage to reduce food loss and waste. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 1251–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geronikou, A.; Srimahaeak, T.; Rantsiou, K.; Triantafillidis, G.; Larsen, N.; Jespersen, L. Occurrence in yeast in white-brined cheeses: Methodologies for identification, spoilage potential and good manufacturing practices. Front. Microb. 2020, 11, 582778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favati, F.; Galgano, F.; Pace, A. Shelf-life evaluation of portioned Provolone cheese packaged in protective atmosphere. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 40, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Lee, S.I.; Rackerby, B.; Goddik, L.; Frojen, R.; Ha, S.; Kim, J.H.; Park, S.H. Microbial communities of a variety of cheeses and comparison between core and rind region of cheeses. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 4026–4042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, D.; Gazzola, S.; Sattin, E.; Dal Bello, F.; Simionati, B.; Cocconcelli, P.S. Lactic acid bacteria adjunct cultures exert a mitigation effect against spoilage microbiota in fresh cheese. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraz, A.R.; Pintado, C.S.; Serralheiro, M.L. A global review of cheese colour: Microbial discolouration and innovation opportunities. Dairy 2024, 5, 768–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carminati, D.; Bonvini, B.; Rossetti, L.; Mariut, M.; Zago, M.; Giraffa, G. Identification and characterization of the microbial agent responsible for an alteration in spoiled, Grana Padano cheese during ripening. Food Control 2023, 155, 110050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossetti, L.; Giraffa, G. Rapid identification of dairy lactic acid bacteria by M13-generated, RAPD-PCR fingerprint databases. J. Microbiol. Meth. 2005, 63, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geronikou, A.; Larsen, N.; Lillevang, S.K.; Jespersen, L. Occurrence and identification of yeasts in production of white-brined cheese. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zago, M.; Rossetti, L.; Bardelli, T.; Carminati, D.; Nazzicari, N.; Giraffa, G. Bacterial community of Grana Padano PDO cheese and generical hard cheeses: DNA metabarcoding and DNA meta fingerprinting analysis to assess similarities and differences. Foods 2021, 10, 1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzas, J.; Kantt, C.A.; Bodyfelt, F.; Torres, J.A. Simultaneous determination of sugars and organic acids in cheddar cheese by high-performance liquid chromatography. Food Sci. 1991, 56, 276–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzi, C.; Povolo, M.; Locci, F.; Bernini, V.; Neviani, E.; Gatti, M. Can the development and autolysis of lactic acid bacteria influence the cheese volatile fraction? The case of Grana Padano. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 233, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masotti, F.; Cattaneo, S.; Stuknytė, M.; De Noni, I. Airborne contamination in the food industry: An update on monitoring and disinfection techniques of air. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 90, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira Perez Alonso, V.; Gonçalves Lemos, J.; da Silva do Nascimento, M. Yeast biofilms on abiotic surfaces: Adhesion factors and control methods. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 400, 110265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zara, G.; Budroni, M.; Mannazzu, I.; Fancello, F.; Zara, S. Yeast biofilm in food realms: Occurrence and control. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 36, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, M.; Bottari, B.; Lazzi, C.; Neviani, E.; Mucchetti, G. Invited review: Microbial evolution in raw-milk, long-ripened cheeses produced using undefined natural whey starters. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 573–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beniwal, A.; Saini, P.; Kokkiligadda, A.; Vij, S. Physiological growth and galactose utilization by dairy yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus in mixed sugars and whey during fermentation. Biotechnology 2017, 7, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Hong, M.; Jung, S.; Ha, S.; Yu, B.J.; Koo, H.M.; Park, S.M.; Seo, J.; Kweon, D.; Park, J.C.; et al. Improved galactose fermentation of Saccharomyces cerevisiae through inverse metabolic engineering. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2011, 108, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidona, F.; Monti, L.; Povolo, M.; Bonvini, B.; Fergonzi, G.; Barzaghi, S.; Locci, F.; Pellegrino, L.; Contarini, G.; Carminati, D. La qualità e sicurezza del formaggio Provolone Valpadana piccante prodotto con latte crudo stoccato a due diverse temperature. Quality and safety of spicy Provolone Valpadana cheese produced with raw milk stored at two different temperatures. Sci. Tec. Latt. Casearia 2022, 72, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Tempel, T.; Jakobsen, M. The technological characteristics of Debaryomyces hansenii and Yarrowia lipolytica and their potential as starter cultures for production of Danablu. Int. Dairy J. 2020, 10, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bintsis, T. Yeasts in different types of cheese. AIMS Microbiol. 2021, 7, 447–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fröhlich-Wyder, M.; Arias-Roth, E.; Jakob, E. Cheese yeasts. Yeast 2019, 36, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coloretti, F.; Chiavari, C.; Luise, D.; Tofalo, R.; Fasoli, G.; Suzzi, G.; Grazia, L. Detection and identification of yeasts in natural whey starters for Parmigiano Reggiano cheese-making. Int. Dairy J. 2017, 66, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, S.; Bonazzi, M.; Malorgio, I.; Pizzamiglio, V.; Tagliazucchi, D.; Solieri, L. Characterization of yeasts isolated from Parmigiano Reggiano cheese natural whey starter: From spoilage agents to potential cell factories for whey valorization. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (A) | |||||||||

| Samples | pH | Lactose | Glucose | Galactose | Lactic Acid | Acetic Acid | Succinic Acid | Propionic Acid | Butyric Acid |

| curd before maturation | 5.74 | 1.52 | 0.41 | 0.54 | 0.32 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| curd after maturation | 5.01 | 0.05 | 0.15 | 0.61 | 1.05 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| curd after stretching | 4.97 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.27 | 1.06 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| PV cheese 30 days | 5.43 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 1.16 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| PV cheese 60 days | 5.44 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.33 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| PV cheese 90 days | 5.49 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.38 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| (B) | |||||||||

| Samples | pH | Lactose | Glucose | Galactose | Lactic Acid | Acetic Acid | Succinic Acid | Propionic Acid | Butyric Acid |

| curd before maturation | 6.30 | 1.60 | 0.14 | 0.27 | 0.19 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| curd after maturation | 4.94 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.37 | 1.32 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| curd after stretching | 4.87 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 1.33 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| PV cheese 30 days | 5.38 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.34 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| PV cheese 60 days | 5.36 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.36 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| PV cheese 90 days | 5.46 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.34 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| 2-propanol | 23.2 | ±0.4 |

| ethanol | 298.0 | ±8.8 |

| 1-propanol | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 2-methyl-1-propanol | 5.8 | ±0.3 |

| 2-pentanol | 1.3 | ±0.1 |

| 1-butanol | 12.6 | ±1.9 |

| 3-methyl-1-butanol | 25.6 | ±0.4 |

| 3-buten-1-ol, 3-methyl | 7.8 | ±0.8 |

| 2-buten-1-ol, 3-methyl | 3.2 | ±0.5 |

| 2-butanol | 3.4 | ±0.6 |

| S of alcohols | 381.1 | ±13.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zago, M.; Bonvini, B.; Rossetti, L.; Povolo, M.; Ballasina, L.; Pisani, V.E.; Tidona, F.; Giraffa, G. Detection, Identification, and Diffusion of Yeasts Responsible for Structural Defects in Provolone Valpadana PDO Cheese Using Multiple Research Techniques. Foods 2026, 15, 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010129

Zago M, Bonvini B, Rossetti L, Povolo M, Ballasina L, Pisani VE, Tidona F, Giraffa G. Detection, Identification, and Diffusion of Yeasts Responsible for Structural Defects in Provolone Valpadana PDO Cheese Using Multiple Research Techniques. Foods. 2026; 15(1):129. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010129

Chicago/Turabian StyleZago, Miriam, Barbara Bonvini, Lia Rossetti, Milena Povolo, Luca Ballasina, Vittorio Emanuele Pisani, Flavio Tidona, and Giorgio Giraffa. 2026. "Detection, Identification, and Diffusion of Yeasts Responsible for Structural Defects in Provolone Valpadana PDO Cheese Using Multiple Research Techniques" Foods 15, no. 1: 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010129

APA StyleZago, M., Bonvini, B., Rossetti, L., Povolo, M., Ballasina, L., Pisani, V. E., Tidona, F., & Giraffa, G. (2026). Detection, Identification, and Diffusion of Yeasts Responsible for Structural Defects in Provolone Valpadana PDO Cheese Using Multiple Research Techniques. Foods, 15(1), 129. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010129