An Exploratory Study on the Impact of MIPEF-Assisted Extraction on Recovery of Proteins, Pigments, and Polyphenols from Sub-Standard Pea Waste

Abstract

1. Introduction

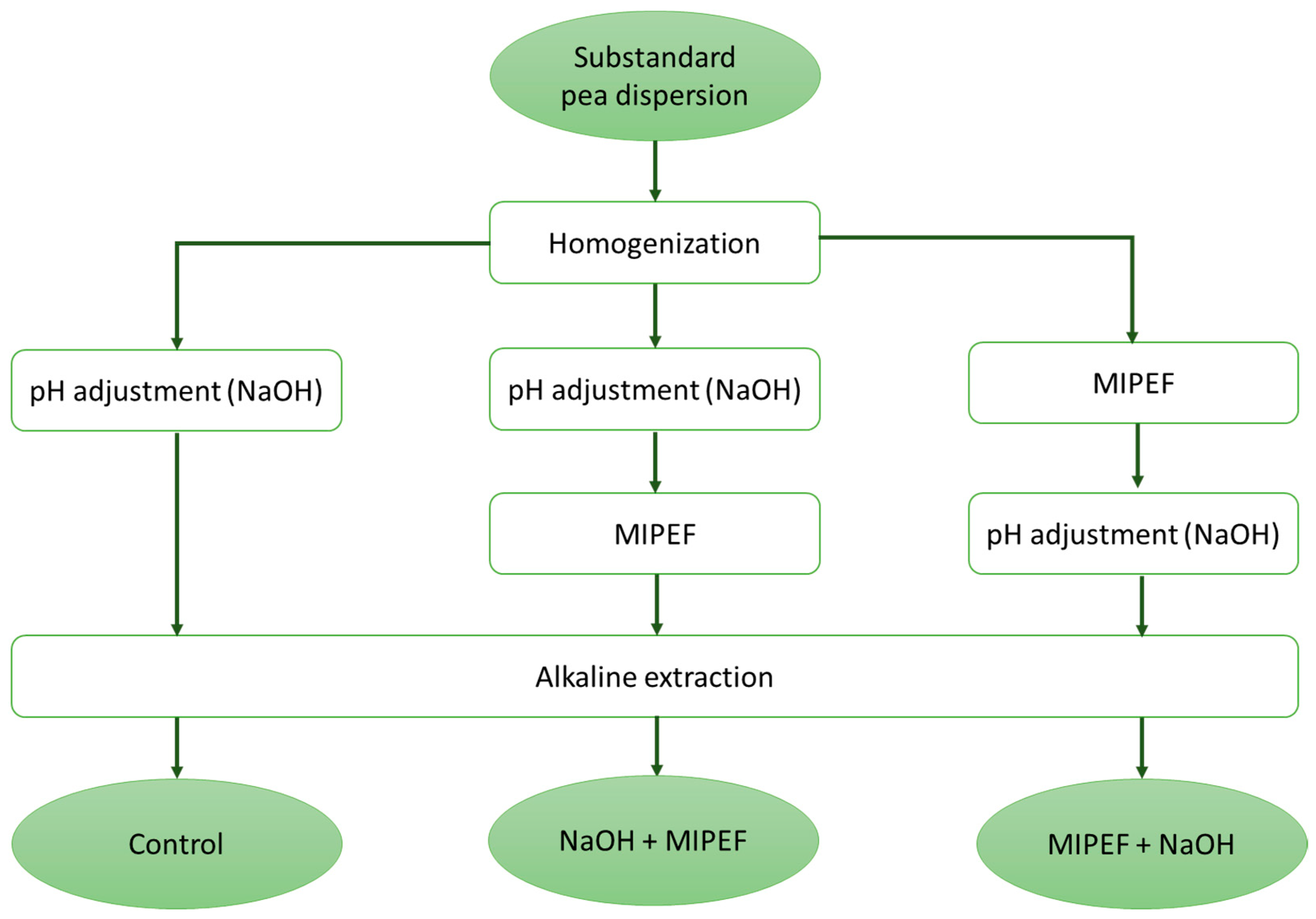

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Vegetable Material

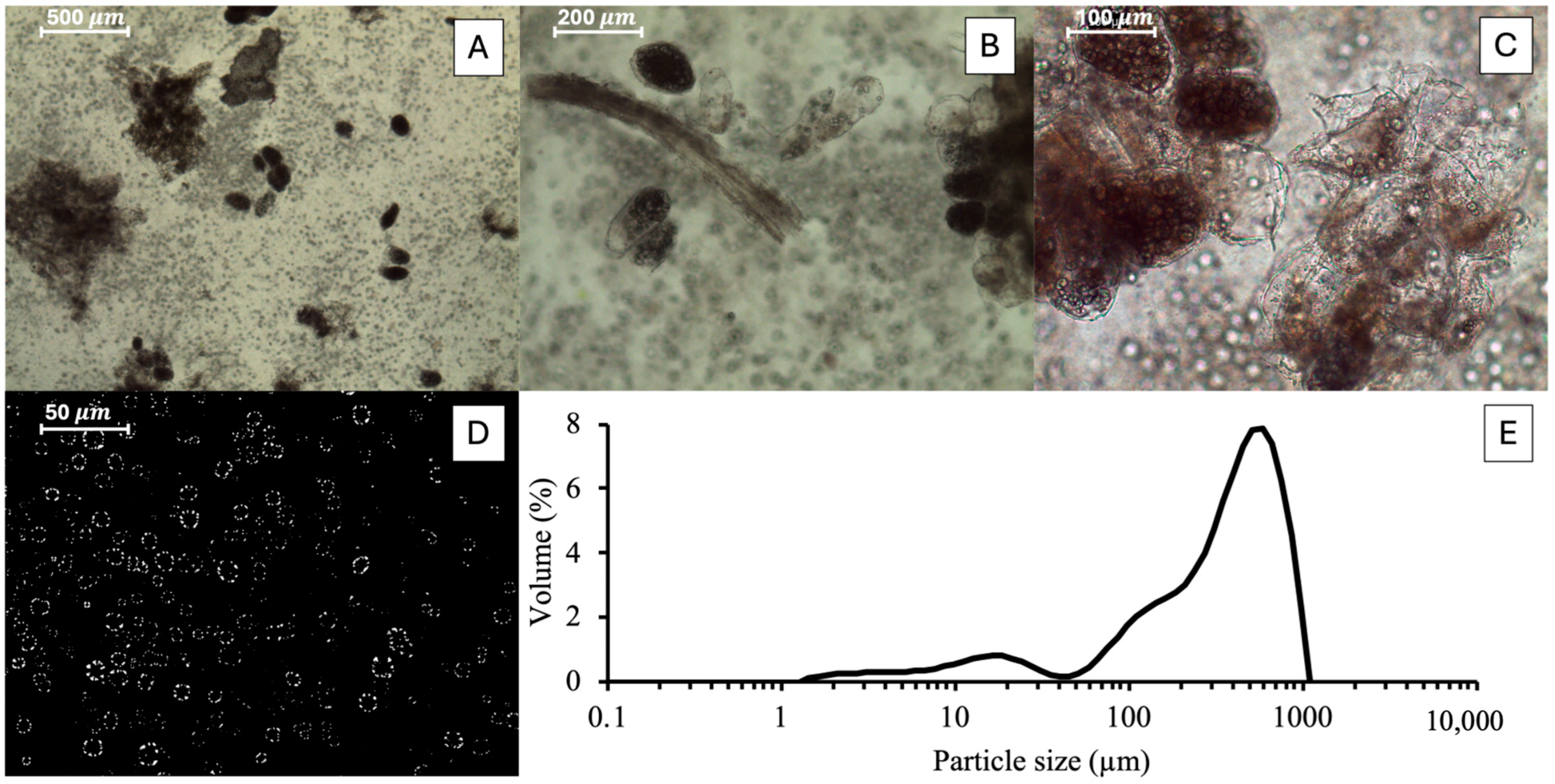

2.2. Preparation of Substandard Pea Dispersions

2.3. pH Adjustment

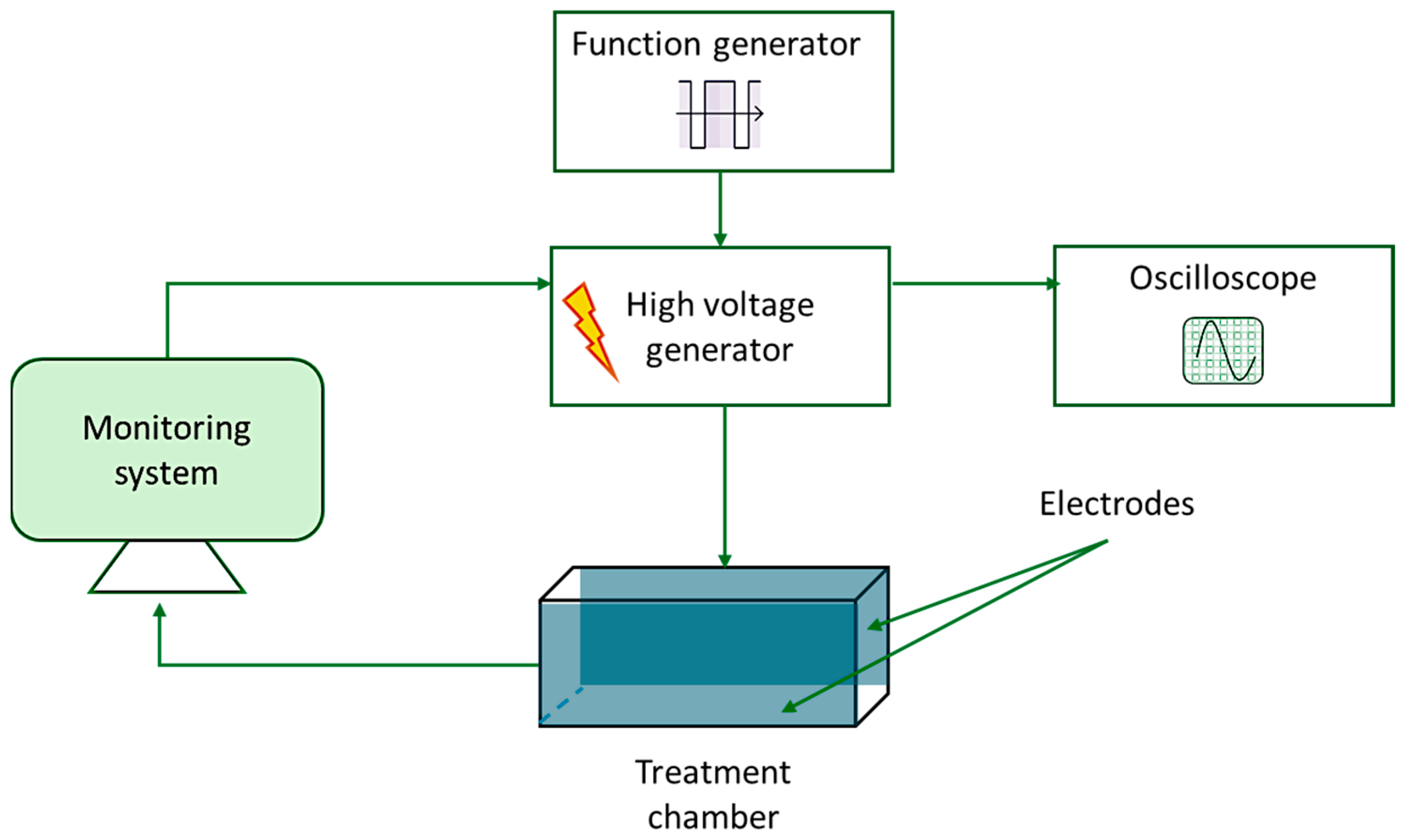

2.4. MIPEF Treatment

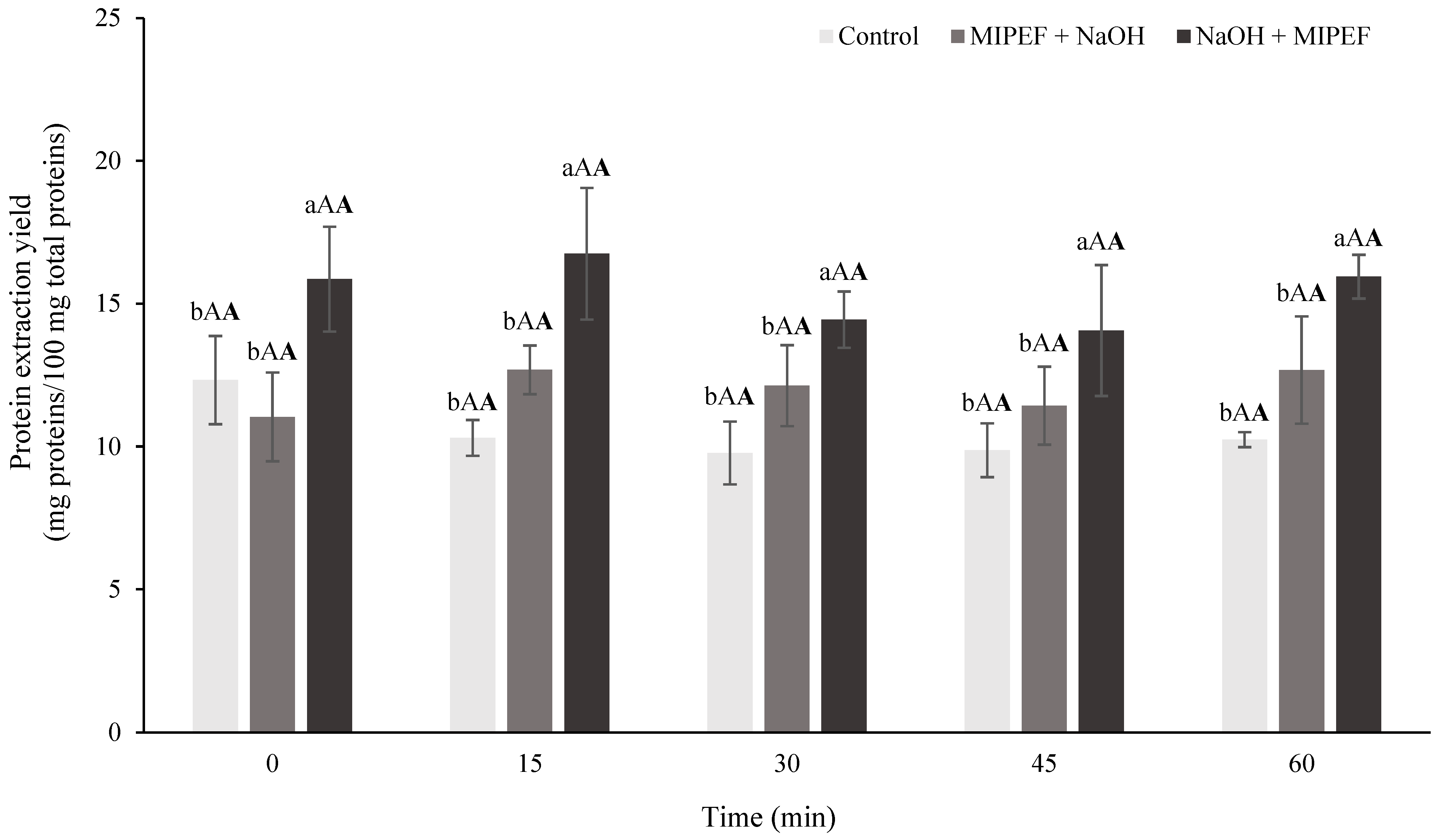

2.5. Alkaline Extraction

2.6. Extract Separation

2.7. Dry Matter

2.8. Optical Microscopy

2.9. Particle Size Distribution

2.10. Protein Content

2.11. Polyphenol Content

2.12. Pigment Content

2.13. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Food Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The Future of Food Agriculture—Alternative Pathways to 2050; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018; p. 224. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1); United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, P.J.; Steinfeld, H.; Henderson, B.; Mottet, A.; Opio, C.; Dijkman, J.; Falcucci, A.; Tempio, G. Tackling Climate Change Through Livestock: A Global Assessment of Emissions and Mitigation Opportunities; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2013; ISBN 978-92-5-107920-1. [Google Scholar]

- Tassoni, A.; Tedeschi, T.; Zurlini, C.; Cigognini, I.M.; Petrusan, J.-I.; Rodríguez, Ó.; Neri, S.; Celli, A.; Sisti, L.; Cinelli, P.; et al. State-of-the-art production chains for peas, beans and chickpeas—Valorization of agro-industrial residues and applications of derived extracts. Molecules 2020, 25, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, I.; Ascione, A.; Muthanna, F.M.S.; Feraco, A.; Camajani, E.; Gorini, S.; Armani, A.; Caprio, M.; Lombardo, M. Sustainable strategies for increasing legume consumption: Culinary and educational approaches. Foods 2023, 12, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, A.C.; Nickerson, M.T. Developing value-added protein ingredients from wastes and byproducts of pulses: Challenges and opportunities. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 18192–18196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Biase, M.; Caponio, G.R.; Cifarelli, V.; Lonigro, S.L.; Pulpito, M.; Grandolfo, C.; Difonzo, G.; Calligaris, S.; Plazzotta, S.; Tamma, G.; et al. Sub-Standard Peas Valorization through Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum Fermentation to Produce a Biologically Active Ingredient for Bread Fortification. App. Food Res. 2025, 5, 101515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzocco, L.; Barozzi, L.; Plazzotta, S.; Sun, Y.; Miao, S.; Calligaris, S. Feasibility of Water-to-Ethanol Solvent Exchange Combined with Supercritical CO2 Drying to Turn Pea Waste into Food Powders with Target Technological and Sensory Properties. LWT 2024, 194, 115778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Liu, G.; Ren, J.; Deng, Q.; Xu, X.; Zhang, J. Current progress in the extraction, functional properties, interaction with polyphenols, and application of legume protein. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 992–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mession, J.L.; Sok, N.; Assifaoui, A.; Saurel, R. Thermal denaturation of pea globulins (Pisum sativum L.)—Molecular interactions leading to heat-induced protein aggregation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 1196–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaafsma, G. Criteria and significance of dietary protein sources in humans: The protein digestibility-corrected amino acid score. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 1865S–1867S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karabulut, G.; Yildiz, S.; Karaca, A.C.; Yemiş, O. Ultrasound and enzyme-pretreated extraction for the valorization of pea pod proteins. J. Food Process Eng. 2023, 46, e14452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooja, B.K.; Sethi, S.; Bhardwaj, R.; Chawla, G.; Kumar, R.; Joshi, A.; Bhowmik, A. Isoelectric precipitation of protein from pea pod and evaluation of its physicochemical and functional properties. Vegetos 2024, 37, 1131–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, S.; Karabulut, G.; Karaca, A.C.; Yemiş, O. Ultrasound-induced modification of pea pod protein concentrate. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2025, 10, 101031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, L.; Bu, F.; Ismail, B.P. Structure-function guided extraction and scale-up of pea protein isolate production. Foods 2022, 11, 3773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asen, N.D.; Aluko, R.E.; Martynenko, A.; Utioh, A.; Bhowmik, P. Yellow field pea protein (Pisum sativum L.): Extraction technologies, functionalities, and applications. Foods 2023, 12, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alinaqui, Z.; Emam-Djomeh, Z.; Salami, M.; Askari, G.; Aliabbasi, N. Black pea protein extraction and investigation of physicochemical characteristics. J. Food Process Preserv. 2024, 2025, 2966339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fendri, L.B.; Chaari, F.; Kallel, F.; Koubaa, M.; Zouari-Ellouzi, S.; Kacem, I.; Chaabouni, S.E.; Ghribi-Aydi, D. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of polyphenols extracted from pea and broad bean pod wastes. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2022, 16, 4822–4832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Ma, G.; Hai, D.; Bai, G.; Guo, Q.; Wang, T.; Huang, X.; Song, L. A comprehensive story of pea peptides and pea polyphenols: Research status, existing problems, and development trends. Food Chem. 2025, 495, 146428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Sarteshnizi, R.A.; Udenigwe, C.C. Recent advances in protein–polyphenol interactions focusing on structural properties related to antioxidant activities. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 45, 100840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelenbos, M.; Christensen, L.P.; Grevsen, K. HPLC determination of chlorophyll and carotenoid pigments in processed green pea cultivars (Pisum sativum L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 4768–4774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V.; Altunakar, B. Pulsed electric fields processing of foods: An overview. In Pulsed Electric Fields Technology for the Food Industry; Raso, J., Heinz, V., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-de-Cerio, E.; Trigueros, E. Evaluating the sustainability of emerging extraction technologies for valorization of food waste: Microwave, ultrasound, enzyme-assisted, and supercritical fluid extraction. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadange, Y.A.; Carpenter, J.; Saharan, V.K. A comprehensive review on advanced extraction techniques for retrieving bio-active components from natural sources. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 31274–31297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naliyadhara, N.; Kumar, A.; Girisa, S.; Daimary, U.D.; Hegde, M.; Kunnumakkara, A.B. Pulsed electric field (PEF): Avant-garde extraction escalation technology in food industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 122, 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.; Amer Eissa, A.H. Pulsed electric fields for food processing technology. In Food Processing Technology: Principles and Practice; Chapter 11; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, C.R.; Kwofie, E.M.; Adewale, P.; Lam, E.; Ngadi, M. Advances in legume protein extraction technologies: A review. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 82, 103199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, R.; Bala Krishnan, S. Pulsed electric field treatment in extracting proteins from legumes: A review. Processes 2024, 12, 2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Xiong, H.; Tsao, R.; Shahidi, F.; Wen, X.; Liu, J.; Jiang, L.; Sun, Y. Green pea (Pisum sativum L.) hull polyphenol extract alleviates NAFLD through VB6/TLR4/NF-κB and PPAR pathways. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 16067–16078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales-de la Peña, M.; Arredondo-Ochoa, T.; Welti-Chanes, J.; Martín-Belloso, O. Application of moderate intensity pulsed electric fields in red prickly pears and soymilk to develop a plant-based beverage with potential health-related benefits. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 88, 103421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchmann, L.; Brändle, I.; Haberkorn, I.; Hiestand, M.; Mathys, A. Pulsed electric field based cyclic protein extraction of microalgae towards closed-loop biorefinery concepts. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 291, 121870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronbauer, M.; Shorstkii, I.; Botelho da Silva, S.; Toepfl, S.; Lammerskitten, A.; Siemer, C. Pulsed electric field assisted extraction of soluble proteins from nettle leaves (Urtica dioica L.): Kinetics and optimization using temperature and specific energy. Sustain. Food Technol. 2023, 1, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luengo, E.; Álvarez, I.; Raso, J. Improving carotenoid extraction from tomato waste by pulsed electric fields. Front. Nutr. 2014, 1, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocker, R.; Silva, E.K. Pulsed electric field assisted extraction of natural food pigments and colorings from plant matrices. Food Chem. X 2022, 15, 100398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazón, P.; Sánchez Silva, A. Natural pigments from food wastes: New approaches for the extraction and encapsulation. Curr. Opin. Green. Sustain. Chem. 2024, 47, 100929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karam, M.C.; Petit, J.; Zimmer, D.; Baudelaire Djantou, E.; Scher, J. Effects of drying and grinding in production of fruit and vegetable powders: A review. J. Food Eng. 2016, 188, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odriozola-Serrano, I.; Soliva-Fortuny, R.; Gimeno-Añó, V.; Martín-Belloso, O. Modeling changes in health-related compounds of tomato juice treated by high-intensity pulsed electric fields. J. Food Eng. 2008, 89, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liao, X.; Ni, Y.; Wu, J.; Hu, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, F. Kinetic analysis of the degradation and its color change of cyanidin-3-glucoside exposed to pulsed electric field. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2007, 224, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC International. Official Methods of Analysis, 17th ed.; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC International. Official Method 2001.11—Protein (crude) in animal feed, forage (plant tissue), grain, and oilseeds (combustion method). In Official Methods of Analysis, 18th ed.; Horwitz, W., Ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sosulski, F.W.; Imafidon, G.I. Amino acid composition and nitrogen-to-protein conversion factors for animal and plant foods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1990, 38, 1351–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé, D.; Cordella, C.; Dib, O.; Péron, C. Nitrogen and Protein Content Measurement and Nitrogen to Protein Conversion Factors for Dairy and Soy Protein-Based Foods: A Systematic Review and Modelling Analysis; World Health Organization and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241516983 (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1999; Volume 299, pp. 152–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaiby, S.; Zhao, X.; Boesch, C.; Sergeeva, N.N. Sustainable approach towards isolation of photosynthetic pigments from Spirulina and the assessment of their prooxidant and antioxidant properties. Food Chem. 2024, 436, 137653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.T.; Li, W.X.; Wan, J.J.; Hu, Y.C.; Gan, R.Y.; Zou, L. A comprehensive review of pea (Pisum sativum L.): Chemical composition, processing, health benefits, and food applications. Foods 2023, 12, 2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estivi, L.; Brandolini, A.; Catalano, A.; Di Prima, R.; Hidalgo, A. Characterization of industrial pea canning by-product and its protein concentrate obtained by optimized ultrasound-assisted extraction. LWT 2024, 207, 116659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessio, G.; Flamminii, F.; Faieta, M.; Prete, R.; Di Michele, A.; Pittia, P.; Di Mattia, C.D. High pressure homogenization to boost the technological functionality of native pea proteins. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 6, 100499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornet, C.; Venema, P.; Nijsse, J.; van der Linden, E.; van der Goot, A.J.; Meinders, M. Yellow pea aqueous fractionation increases the specific volume fraction and viscosity of its dispersions. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 99, 105332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadidi, M.; Aghababaei, F.; McClements, D.J. Enhanced alkaline extraction techniques for isolating and modifying plant-based proteins. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 145, 109132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, A.C.Y.; Can Karaca, A.; Tyler, R.T.; Nickerson, M.T. Pea protein isolates: Structure, extraction, and functionality. Food Rev. Int. 2018, 34, 126–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincan, M.; DeVito, F.; Dejmek, P. Pulsed electric field treatment for solid–liquid extraction of red beetroot pigment. J. Food Eng. 2004, 64, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barozzi, L.; Plazzotta, S.; Nucci, A.; Manzocco, L. Elucidating the role of compositional and processing variables in tailoring the technological functionalities of plant protein ingredients. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2025, 10, 100971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, G.; Zeng, H.; Chen, L. Effects of high-pressure homogenization on faba bean protein aggregation in relation to solubility and interfacial properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 83, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Y.M.; Jia, S.R.; Sun, Z.; Dale, B.E. Integrating kinetics with thermodynamics to study the alkaline extraction of protein from Caragana korshinskii Kom. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2014, 111, 1801–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Gall, M.; Guéguen, J.; Séve, B.; Quillien, L. Effects of grinding and thermal treatments on hydrolysis susceptibility of pea proteins (Pisum sativum L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 3057–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpentieri, S.; Ferrari, G.; Pataro, G. Pulsed electric fields-assisted extraction of valuable compounds from red grape pomace: Process optimization using response surface methodology. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1158019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melchior, S.; Calligaris, S.; Bisson, G.; Manzocco, L. Understanding the impact of moderate-intensity pulsed electric fields (MIPEF) on structural and functional characteristics of pea, rice and gluten concentrates. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2020, 13, 1581–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, U. Electrical breakdown, electropermeabilization and electrofusion. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1986, 105, 176–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowosad, K.; Sujka, M.; Pankiewicz, U.; Kowalski, R. The application of PEF technology in food processing and human nutrition. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plazzotta, S.; Ibarz, R.; Manzocco, L.; Martín-Belloso, O. Modelling the recovery of biocompounds from peach waste assisted by pulsed electric fields or thermal treatment. J. Food Eng. 2021, 290, 110196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knorr, D.; Angersbach, A. Impact of high-intensity electric field pulses on plant membrane permeabilization. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 1998, 9, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donsì, F.; Ferrari, G.; Pataro, G. Applications of pulsed electric field treatments for the enhancement of mass transfer from vegetable tissue. Food Eng. Rev. 2010, 2, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, B.; Tiwari, B.K.; Walsh, D.; Griffin, T.P.; Islam, N.; Lyng, J.G.; Brunton, N.P.; Rai, D.K. Impact of pulsed electric field pre-treatment on nutritional and polyphenolic contents and bioactivities of light and dark brewer’s spent grains. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2019, 54, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsimichas, A.; Stathi, S.; Dimopoulos, G.; Giannakourou, M.; Taoukis, P. Kinetics of pulsed electric fields assisted pigment extraction from Chlorella pyrenoidosa. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 91, 103547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cholet, C.; Delsart, C.; Petrel, M.; Gontier, E.; Grimi, N.; L’Hyvernay, A.; Ghidossi, R.; Vorobiev, E.; Mietton-Peuchot, M.; Gény, L. Structural and biochemical changes induced by pulsed electric field treatments on Cabernet Sauvignon grape berry skins: Impact on cell wall total tannins and polysaccharides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 2925–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, L.H.; Wen, Q.H.; He, F.; Xu, F.Y.; Chen, B.R.; Zeng, X.A. Combination of pulsed electric field and pH shifting improves the solubility, emulsifying, and foaming of commercial soy protein isolate. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 134, 108049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.H.; Huang, X.; Wang, L.H.; Li, J.; Zeng, X.A.; Gao, X. Pulsed electric fields disaggregating chlorophyll aggregates and boosting its biological activity. Food Res. Int. 2025, 208, 116153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Dispersion pH | R (Ω) | σ (mS/cm) | Uk (kV) | Rtrasf (−) | E (kV/cm) | Ik (A) | Wp (kJ/(kg pulse)) | Wt (kJ/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.7 (native) | 254.1 ± 7.0 a | 0.52 ± 0.01 b | 8.27 ± 0.12 a | 23.62 ± 0.32 a | 5.51 ± 0.08 a | 32.55 ± 0.45 b | 2.36 ± 0.05 b | 1178 ± 23 b |

| 9.0 | 198.4 ± 4.8 b | 0.62 ± 0.13 a | 8.07 ± 0.09 b | 23.02 ± 0.28 a | 5.34 ± 0.00 b | 40.63 ± 1.11 a | 3.01 ± 0.09 a | 1506 ± 45 a |

| Dispersion pH | R (Ω) | σ (mS/cm) | Ik (A) | Wp (kJ/(kg pulse)) | Wt (kJ/kg) | Protein Extraction Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10.0 | 151.0 ± 9.4 a | 0.89 ± 0.05 b | 53.13 ± 3.32 b | 3.81 ± 0.20 b | 1904 ± 99 a | 15.5 ± 1.1 a |

| 11.0 | 143.4 ± 4.3 a | 0.93 ± 0.03 b | 55.86 ± 1.65 b | 3.98 ± 0.09 b | 1993 ± 46 a | 14.6 ± 2.3 a |

| 12.0 | 103.8 ± 10.8 b | 1.30 ± 0.13 a | 76.56 ± 6.63 a | 5.16 ± 0.37 a | 2578 ± 183 b | 15.0 ± 1.9 a |

| Extract | TPC (mgGAE/gdm) | Chlorophyll A (μg/gdm) | Chlorophyll B (μg/gdm) | Carotenoids (μg/gdm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 1.40 ± 0.01 a | 49.7 ± 4.9 a | 21.3 ± 1.2 a | 16.1 ± 0.3 a |

| MIPEF | 1.20 ± 0.01 b | 30.3 ± 1.0 b | 14.8 ± 0.3 b | 9.8 ± 0.1 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Plazzotta, S.; Saitta, A.; Melchior, S.; Manzocco, L. An Exploratory Study on the Impact of MIPEF-Assisted Extraction on Recovery of Proteins, Pigments, and Polyphenols from Sub-Standard Pea Waste. Foods 2026, 15, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010128

Plazzotta S, Saitta A, Melchior S, Manzocco L. An Exploratory Study on the Impact of MIPEF-Assisted Extraction on Recovery of Proteins, Pigments, and Polyphenols from Sub-Standard Pea Waste. Foods. 2026; 15(1):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010128

Chicago/Turabian StylePlazzotta, Stella, Alberto Saitta, Sofia Melchior, and Lara Manzocco. 2026. "An Exploratory Study on the Impact of MIPEF-Assisted Extraction on Recovery of Proteins, Pigments, and Polyphenols from Sub-Standard Pea Waste" Foods 15, no. 1: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010128

APA StylePlazzotta, S., Saitta, A., Melchior, S., & Manzocco, L. (2026). An Exploratory Study on the Impact of MIPEF-Assisted Extraction on Recovery of Proteins, Pigments, and Polyphenols from Sub-Standard Pea Waste. Foods, 15(1), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010128