Cross-Platform Evaluation of Established NGS-Based Metabarcoding Methods for Detecting Food Fraud in Pistachio Products

Abstract

1. Introduction

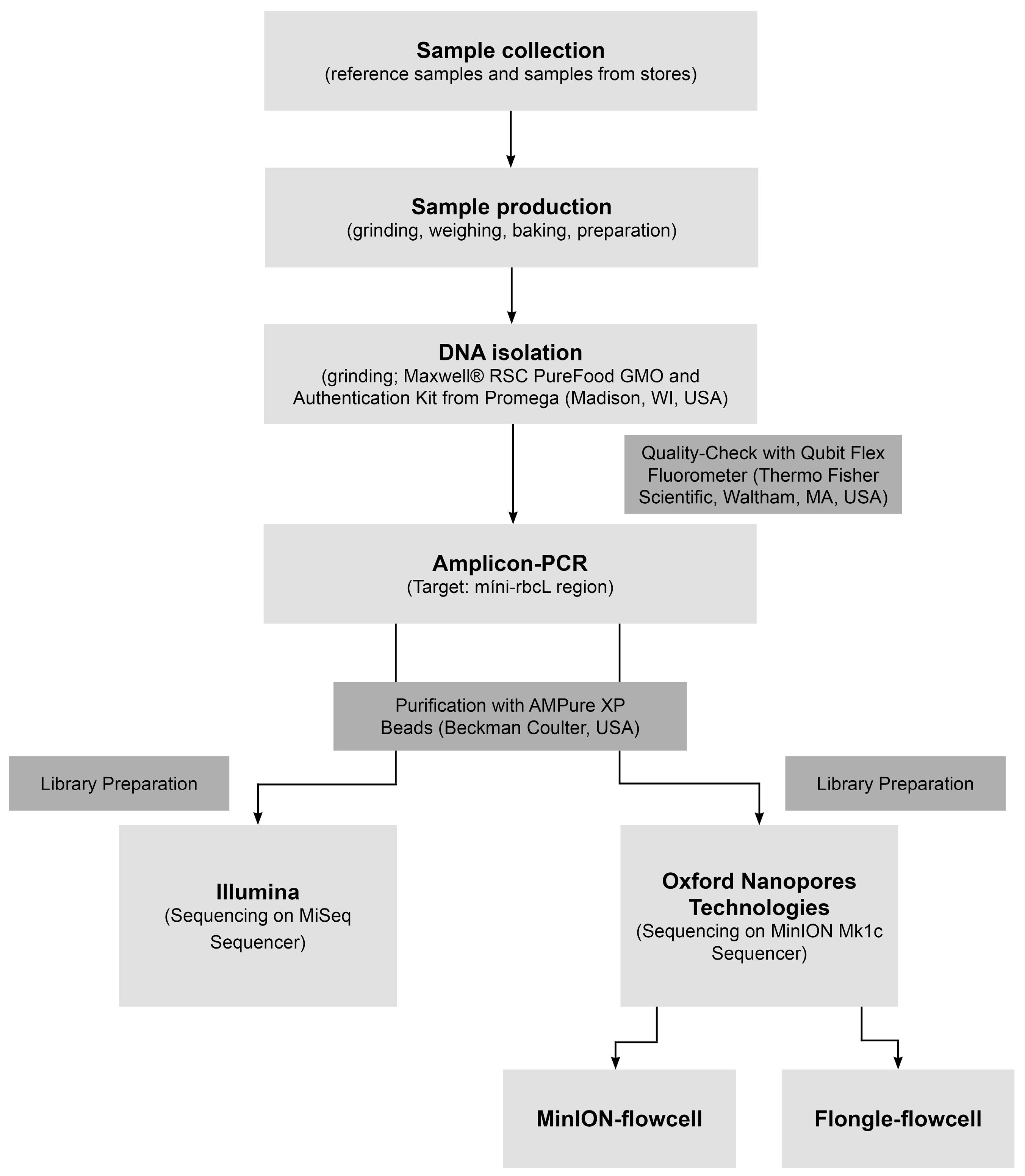

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples and Sample Preparation

2.2. DNA Extraction and Amplicon PCR

- Forward (F52): TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGTTGGATTCAAAGCTGGTGTTA

- Reverse (R193): GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGCVGTCCAMACAGTWGTCCATGT

2.3. Library Preparation ONT Seq

2.4. Library Preparation and NGS

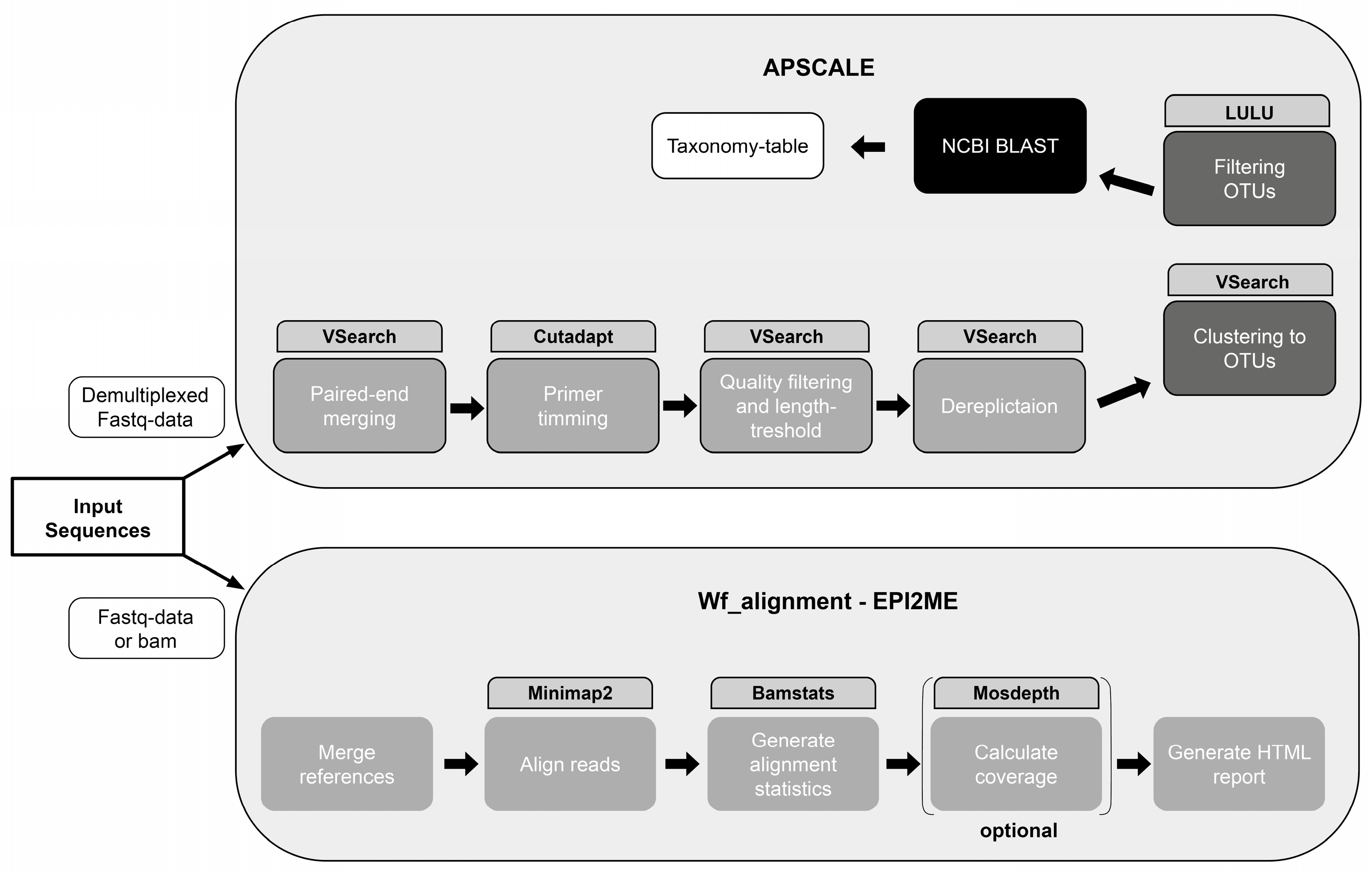

2.5. NGS Data Analysis

2.5.1. Data Analysis Oxford Nanopore Technologies

2.5.2. Data Analysis Illumina

3. Results and Discussion

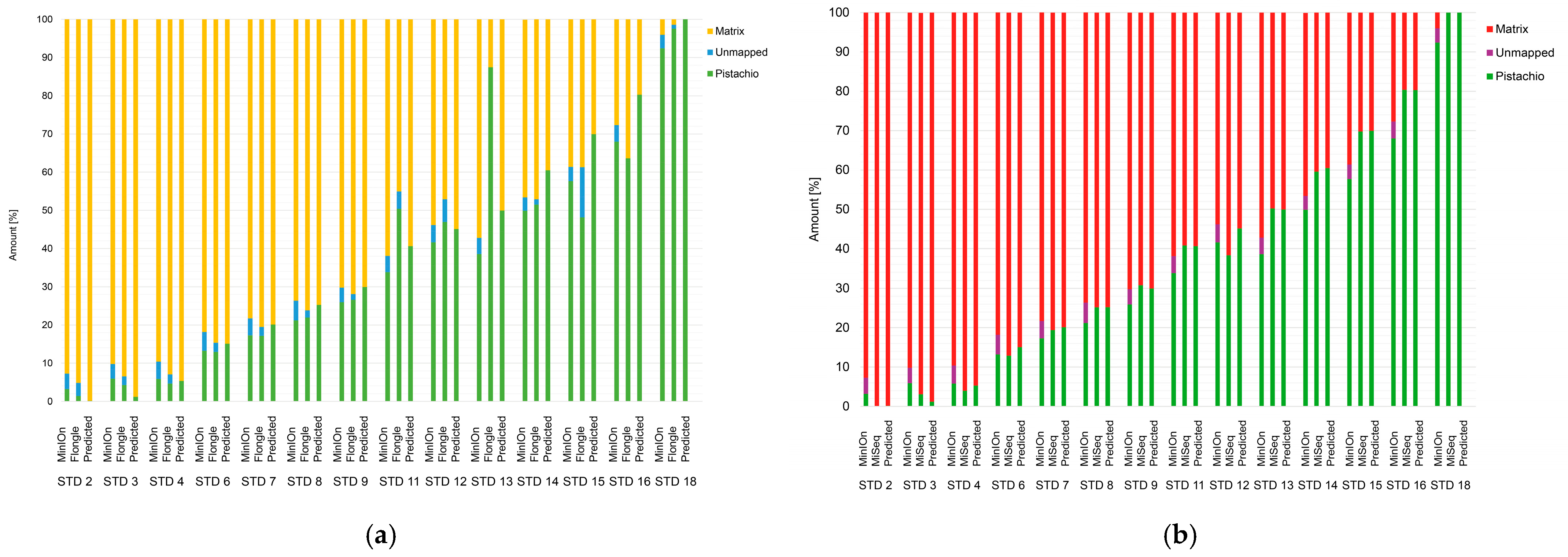

3.1. Results: Reference Samples and Standard Samples with ONT

3.1.1. ONT wf_alignment_workflow

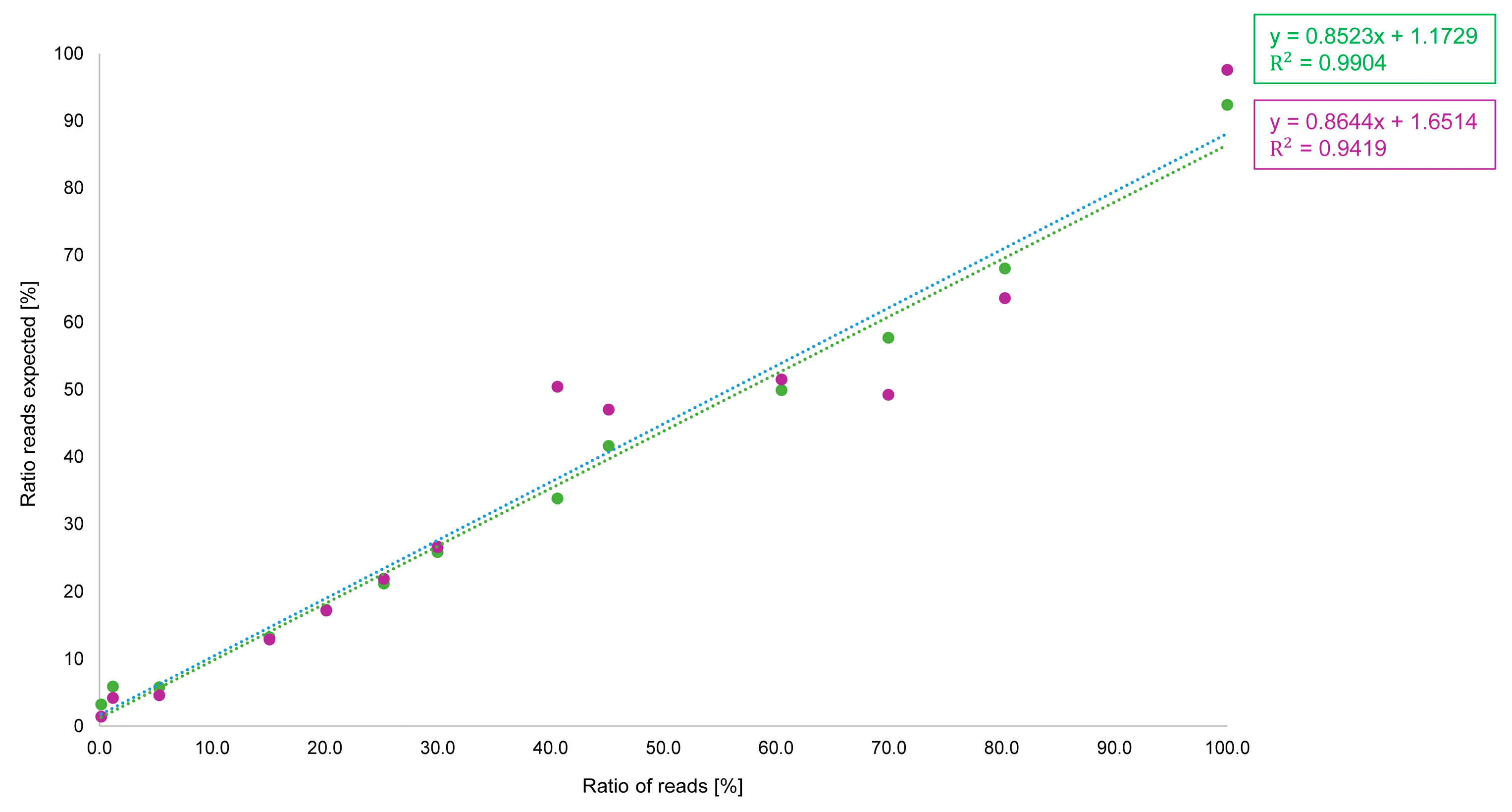

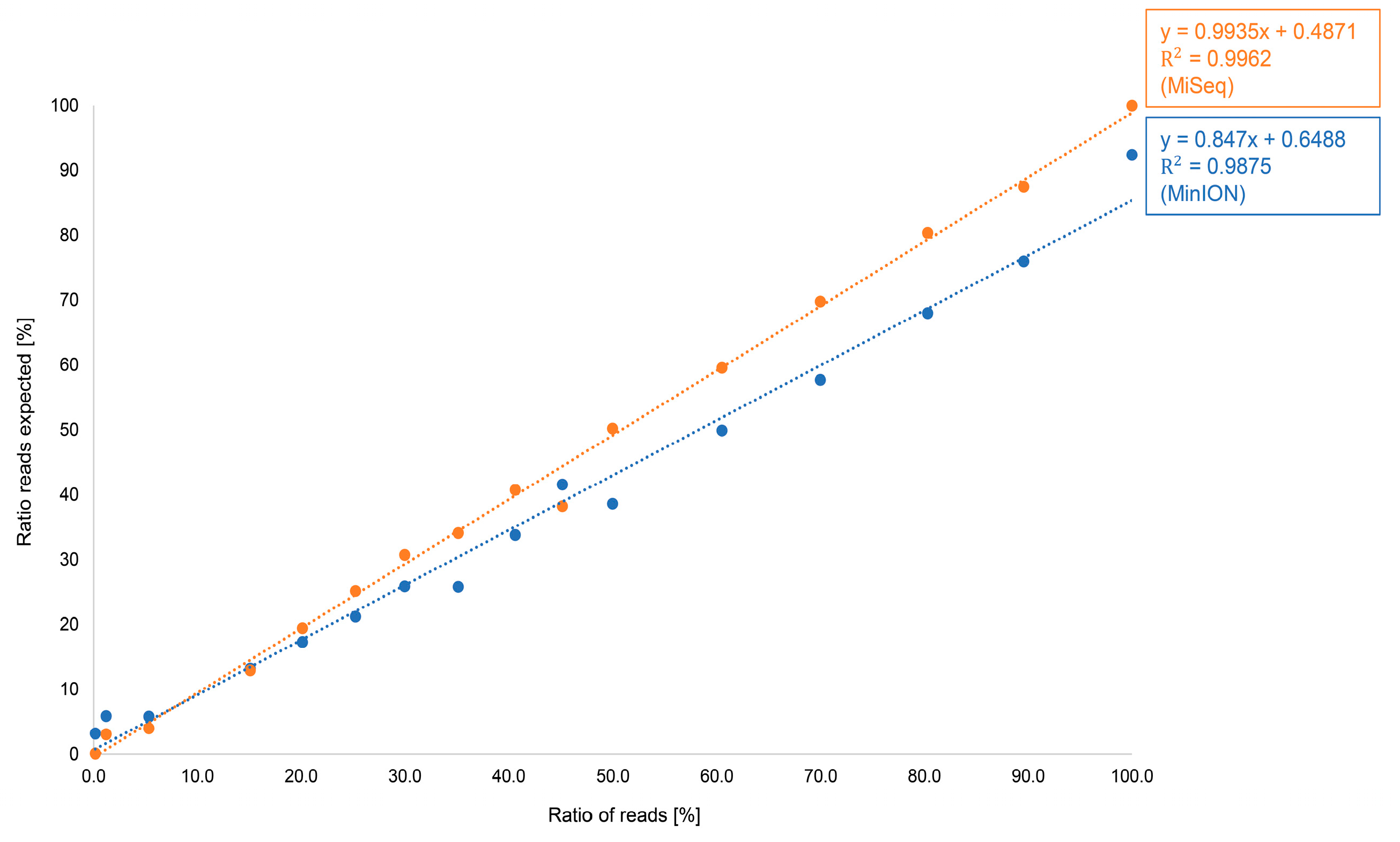

3.1.2. Comparison of Illumina and Oxford Nanopore Technologies

3.2. Results: Pistachio Products

| Sample ID | Categories of Homogenization | Pistachio Content Declared [%] | Amount Detected [%] MinION | Amount Detected [%] MiSeq |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP1 | 1 | 17 | 65.2 | 74.3 |

| PP2 | 2 | 16 | 83.9 | 92.3 |

| PP3 | 2 | 25 | 98.2 | 100 |

| PP4 | 2 | 30 | 98.3 | 99.8 |

| PP5 | 2 | 35 | 96.5 | 100 |

| PP6 | 2 | 25 | 97.4 | 100 |

| PP7 | 2 | 100 | 97.3 | 100 |

| PP8 | 1 | 17 | 65.7 | 72.2 |

| PP9 | 1 | 12 | 76.1 | 82.1 |

| PP10 | 1 | 15 | 58.4 | 67.3 |

| PP11 | 1 | 15 | 44.4 | 52.8 |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Winand, R.; Bogaerts, B.; Hoffman, S.; Lefevre, L.; Delvoye, M.; Van Braekel, J.; Fu, Q.; Roosens, N.H.; De Keersmaecker, S.C.; Vanneste, K. Targeting the 16s rRNA gene for bacterial identification in complex mixed samples: Comparative evaluation of second (illumina) and third (oxford nanopore technologies) generation sequencing technologies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 21, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aird, D.; Ross, M.G.; Chen, W.-S.; Danielsson, M.; Fennell, T.; Russ, C.; Jaffe, D.B.; Nusbaum, C.; Gnirke, A. Analyzing and minimizing PCR amplification bias in Illumina sequencing libraries. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoads, A.; Au, K.F. PacBio sequencing and its applications. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2015, 13, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ying, C.; Wang, D.; Du, C. Nanopore-based fourth-generation DNA sequencing technology. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2015, 13, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosher, J.J.; Bowman, B.; Bernberg, E.L.; Shevchenko, O.; Kan, J.; Korlach, J.; Kaplan, L.A. Improved performance of the PacBio SMRT technology for 16S rDNA sequencing. J. Microbiol. Methods 2014, 104, 59–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myer, P.R.; Kim, M.; Freetly, H.C.; Smith, T.P. Evaluation of 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing using two next-generation sequencing technologies for phylogenetic analysis of the rumen bacterial community in steers. J. Microbiol. Methods 2016, 127, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quail, M.A.; Smith, M.; Coupland, P.; Otto, T.D.; Harris, S.R.; Connor, T.R.; Bertoni, A.; Swerdlow, H.P.; Gu, Y. A tale of three next generation sequencing platforms: Comparison of Ion Torrent, Pacific Biosciences and Illumina MiSeq sequencers. BMC Genom. 2012, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; van Aerle, R.; Barrientos, L.; Martinez-Urtaza, J. Computational methods for 16S metabarcoding studies using Nanopore sequencing data. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 296–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How Basecalling Works. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20251013122823/https://nanoporetech.com/platform/technology/basecalling (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Cuber, P.; Chooneea, D.; Geeves, C.; Salatino, S.; Creedy, T.J.; Griffin, C.; Sivess, L.; Barnes, I.; Price, B.; Misra, R. Comparing the accuracy and efficiency of third generation sequencing technologies, Oxford Nanopore Technologies, and Pacific Biosciences, for DNA barcode sequencing applications. Ecol. Genet. Genom. 2023, 28, 100181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Reis, A.L.; Beckley, L.E.; Olivar, M.P.; Jeffs, A.G. Nanopore short-read sequencing: A quick, cost-effective and accurate method for DNA metabarcoding. Environ. DNA 2023, 5, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulandhu, A.J.; Staats, M.; Hagelaar, R.; Voorhuijzen, M.M.; Prins, T.W.; Scholtens, I.; Costessi, A.; Duijsings, D.; Rechenmann, F.; Gaspar, F.B. Development and validation of a multi-locus DNA metabarcoding method to identify endangered species in complex samples. Gigascience 2017, 6, gix080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, D.; Srivathsan, A.; Meier, R. Longer is not always better: Optimizing barcode length for large-scale species discovery and identification. Syst. Biol. 2020, 69, 999–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruppert, K.M.; Kline, R.J.; Rahman, M.S. Past, present, and future perspectives of environmental DNA (eDNA) metabarcoding: A systematic review in methods, monitoring, and applications of global eDNA. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2019, 17, e00547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammouz, S.; Reichstein, A.; Riehle, J.; Ferner, A.; Fischer, M.; Schäfers, C. Authenticity in bakery products: Detection of pistachio fraud using NGS metabarcoding. Food Chem. Mol. Sci. 2025, 10, 100260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eksi-Kocak, H.; Mentes-Yilmaz, O.; Boyaci, I.H. Detection of green pea adulteration in pistachio nut granules by using Raman hyperspectral imaging. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2016, 242, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchiz, Á.; Ballesteros, I.; Martin, A.; Rueda, J.; Pedrosa, M.M.; del Carmen Dieguez, M.; Rovira, M.; Cuadrado, C.; Linacero, R. Detection of pistachio allergen coding sequences in food products: A comparison of two real time PCR approaches. Food Control 2017, 75, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torricelli, M.; Pierboni, E.; Rondini, C.; Altissimi, S.; Haouet, N. Sesame, Pistachio, and Macadamia Nut: Development and Validation of New Allergenic Systems for Fast Real-Time PCR Application. Foods 2020, 9, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Peng, H.; Ma, J.; Li, H.; Li, L.; Li, T.; Fang, Z.; Ma, A.; Fu, L. High-Throughput Identification of Allergens in a Food System via Hybridization Probe Cluster-Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 11992–12001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, E.; Jimenez, E.; Pardo, M.A.; Helyar, S.J. The future of NGS (Next Generation Sequencing) analysis in testing food authenticity. Food Control 2019, 101, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ay, N.; Hürkan, K. A novel high-resolution melting method for detection of adulteration on pistachio (Pistacia vera L.). Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2023, 66, e23220550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aykas, D.P.; Menevseoglu, A. A rapid method to detect green pea and peanut adulteration in pistachio by using portable FT-MIR and FT-NIR spectroscopy combined with chemometrics. Food Control 2021, 121, 107670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylan, O.; Cebi, N.; Yilmaz, M.T.; Sagdic, O.; Ozdemir, D.; Balubaid, M. Rapid detection of green-pea adulteration in pistachio nuts using Raman spectroscopy and chemometrics. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 1699–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frigerio, J.; Agostinetto, G.; Mezzasalma, V.; De Mattia, F.; Labra, M.; Bruno, A. DNA-Based Herbal Teas’ Authentication: An ITS2 and psbA-trnH Multi-Marker DNA Metabarcoding Approach. Plants 2021, 10, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Han, J.; Yang, M.; Chen, S.; Pang, X. DNA Metabarcoding: Current Applications and Challenges. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 20616–20632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrovolny, S.; Blaschitz, M.; Weinmaier, T.; Pechatschek, J.; Cichna-Markl, M.; Indra, A.; Hufnagl, P.; Hochegger, R. Development of a DNA metabarcoding method for the identification of fifteen mammalian and six poultry species in food. Food Chem. 2019, 272, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Minimap2: Pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3094–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, B.S.; Quinlan, A.R. Mosdepth: Quick coverage calculation for genomes and exomes. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 867–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchner, D.; Macher, T.-H.; Leese, F. APSCALE: Advanced pipeline for simple yet comprehensive analyses of DNA metabarcoding data. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 4817–4819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayers, E.W.; Agarwala, R.; Bolton, E.E.; Brister, J.R.; Canese, K.; Clark, K.; Connor, R.; Fiorini, N.; Funk, K.; Hefferon, T. Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- wf-Alignment. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20251013123110/https://nanoporetech.com/document/epi2me-workflows/wf-alignment (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Srivathsan, A.; Lee, L.; Katoh, K.; Hartop, E.; Kutty, S.N.; Wong, J.; Yeo, D.; Meier, R. ONTbarcoder and MinION barcodes aid biodiversity discovery and identification by everyone, for everyone. BMC Biol. 2021, 19, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu-Wei, W.; van der Toorn, W.; Bohn, P.; Hölzer, M.; Smyth, R.P.; von Kleist, M. Sequencing accuracy and systematic errors of nanopore direct RNA sequencing. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sequencing Quality Scores. Available online: https://emea.illumina.com/science/technology/next-generation-sequencing/plan-experiments/quality-scores.html (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Ranasinghe, D.; Jayadas, T.T.P.; Jayathilaka, D.; Jeewandara, C.; Dissanayake, O.; Guruge, D.; Ariyaratne, D.; Gunasinghe, D.; Gomes, L.; Wijesinghe, A. Comparison of different sequencing techniques for identification of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern with multiplex real-time PCR. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0265220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golenberg, E.M.; Bickel, A.; Weihs, P. Effect of Highly Fragmented DNA on PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996, 24, 5026–5033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Liu, C.; Zheng, X.; Wu, L.; Liu, Z.; Liao, B.; Shi, Y.; Li, X.; Xu, J.; Chen, S. Full-length multi-barcoding: DNA barcoding from single ingredient to complex mixtures. Genes 2019, 10, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Description | Homogenization | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The pistachio content refers to the entire product, although pistachios are only present in certain parts | The whole product has been homogenized and nuclease-free water has been added (if necessary) | Protein bar, cereal bar |

| 2 | The term “pistachio” refers to the whole product and the product is homogenous | Homogenization by stirring | Creams toppings |

| 3 | The pistachio content refers only to parts of the product | The portion of the product has been isolated and homogenized (with nuclease-free water if necessary) | Bakery products |

| Reference Material | Flongle Flow Cell (FLO-FLG114) | MinION Flow Cell (FLO-MIN114) | Spot-ON Flow Cell (FLO-MIN106D) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species Detected | Amount [%] | Species Detected | Amount [%] | Species Detected | Amount [%] | |

| Pistacia vera | Pistacia vera | 93.6 | Pistacia vera | 94.1 | Pistacia vera | 83.3 |

| Juglans regia | Juglans regia | 97.5 | Juglans regia | 97.2 | Juglans regia | 88.2 |

| Prunus dulcis | Prunus dulcis | 78.4 | Prunus dulcis | 97.0 | Prunus dulcis | 79.4 |

| Helianthus annuus | Helianthus annuus | 97.2 | Helianthus annuus | 95.6 | Helianthus annuus | 88.2 |

| Pisum sativum | Pisum sativum | 96.1 | Pisum sativum | 94.6 | Pisum sativum | 80.6 |

| Corylus spp. | Corylus avellana | 95.9 | Corylus avellana | 97.0 | Corylus avellana | 81.1 |

| Cucurbita spp. | Cucurbita moschata | 74.0 | Cucurbita moschata | 79.2 | Cucurbita moschata | 58.9 |

| Flongle Flow Cell | MinION Flow Cell | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Bases [Mb] | Passed Bases [%] | Total Reads [k] | Passed Reads [%] | Amount [%] | Total Bases [Mb] | Passed Bases [%] | Total Reads [k] | Passed Reads [%] | Amount [%] | |

| Pistacia vera | 25.1 | 84.4 | 69.7 | 85.1 | 93.6 | 410.1 | 86.7 | 1071.7 | 89.2 | 94.1 |

| Juglans regia | 9.9 | 86.2 | 28.4 | 86.5 | 97.5 | 447.4 | 86.8 | 1163.1 | 90.8 | 97.2 |

| Prunus dulcis | 4.4 | 85.2 | 12.9 | 86.1 | 78.4 | 483.8 | 86.3 | 1256.1 | 89.1 | 97.0 |

| Helianthus annuus | 46.8 | 84.8 | 129.2 | 85.1 | 97.2 | 276.8 | 87.4 | 744.5 | 89.6 | 95.6 |

| Pisum sativum | 26.6 | 85.4 | 74.7 | 86.1 | 96.1 | 380.9 | 88.1 | 980.3 | 91.3 | 94.6 |

| Corylus spp. | 30.6 | 85.3 | 84.8 | 85.8 | 95.9 | 346.7 | 85.8 | 899.1 | 89.1 | 97.0 |

| Cucurbita spp. | 5.3 | 85.8 | 12.4 | 84.8 | 74.0 | 62.4 | 80.5 | 136.1 | 87.1 | 79.2 |

| Sample ID | Genus Declared in the Nut Layer [%] | Amount Detected [%] MinION | Amount Detected [%] MiSeq 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | Pistacia spp. | 54.5 | 61.0 |

| B2 | Pistacia spp. | 59.2 | 64.6. |

| B3 | Pistacia spp. | 21.2 | 31.7 |

| B4 | Pistacia spp. | 62.4 | 72.5 |

| B5 | Pistacia spp. | 65.2 | 70.4 |

| B6 | Pistacia spp. | 47.6 | 54.4 |

| B7 | Pistacia spp. | 2.2 | 0.5 |

| B8 | Pistacia spp. | 2.8 | 5.2 |

| B9 | Pistacia spp. | 15.6 | 13.2 |

| B10 | Pistacia spp. | 83.9 | 97.8 |

| B11 | Pistacia spp. | 85.0 | 99.9 |

| B12 | Pistacia spp. | 87.9 | 98.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rammouz, S.; Riehle, J.; Ferner, A.; Fischer, M.; Schäfers, C. Cross-Platform Evaluation of Established NGS-Based Metabarcoding Methods for Detecting Food Fraud in Pistachio Products. Foods 2026, 15, 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010124

Rammouz S, Riehle J, Ferner A, Fischer M, Schäfers C. Cross-Platform Evaluation of Established NGS-Based Metabarcoding Methods for Detecting Food Fraud in Pistachio Products. Foods. 2026; 15(1):124. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010124

Chicago/Turabian StyleRammouz, Sina, Jochen Riehle, Ansgar Ferner, Markus Fischer, and Christian Schäfers. 2026. "Cross-Platform Evaluation of Established NGS-Based Metabarcoding Methods for Detecting Food Fraud in Pistachio Products" Foods 15, no. 1: 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010124

APA StyleRammouz, S., Riehle, J., Ferner, A., Fischer, M., & Schäfers, C. (2026). Cross-Platform Evaluation of Established NGS-Based Metabarcoding Methods for Detecting Food Fraud in Pistachio Products. Foods, 15(1), 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010124