1. Introduction

Mushrooms have long been valued not only for their culinary applications but also for their nutritional and medicinal properties. They are rich in bioactive compounds such as polysaccharides, polyphenols, sterols, terpenoids, and essential minerals, which have been associated with antioxidant, anticancer, immunomodulatory, antidiabetic, neuroprotective, and other health-promoting effects [

1,

2,

3,

4].

The edible mushroom industry has become the fifth most significant agricultural sector [

5]. However, large-scale mushroom cultivation results in the generation of substantial amounts of spent mushroom substrate (SMS). On average, for each kilogram of mushrooms produced, approximately five kilograms of waste are generated [

6]. It is projected that by 2026, mushroom cultivation will produce approximately 104 million tons of waste globally [

7]. The accumulation of such waste poses both environmental and economic challenges.

In response to these environmental and economic challenges, there has been growing interest in the value-added utilization of SMS. It has been reported that SMS contains a variety of bioactive compounds and essential nutrients, including antioxidants, lignocellulolytic enzymes, and minerals like potassium and magnesium [

8,

9,

10]. Consequently, its reuse has been studied in agriculture, like soil amendment [

11,

12], upcycled crop substrates [

13], animal feed [

14], environmental remediation [

15,

16], and even food preservation [

17].

Among the diverse metabolites present in mushrooms, notable differences have been observed in their amino acid profile between species [

18]. Ergothioneine (EGT) is a sulfur-containing amino acid synthesized by certain fungi and bacteria. Mushrooms are recognized as the richest dietary source of EGT, although its content varies greatly with species [

19]. EGT exhibits strong antioxidant and cytoprotective properties and has been associated with neuroprotection [

20], cardiovascular health [

21], maternal health during pregnancy [

22], and aging-related outcomes [

23,

24,

25]. It is taken up by the human body via the OCTN1 transporter and is suggested to accumulate in all tissues but preferentially to those predisposed to oxidative stress, including the brain, suggesting a role in neurodegenerative disease prevention [

20,

26,

27].

Animals are incapable of synthesizing EGT endogenously; hence, they must obtain it from their diet, with mushrooms recognized as the richest dietary source. Given that some metabolites, like polysaccharides, sterols, and other compounds, found in fruiting bodies can also be detected in SMS [

28], we hypothesized that SMS may also contain EGT and other valuable bioactive compounds. Furthermore, given that mushrooms are usually cultivated in bags of substrates commercially and each batch of cultivation bag may fruit more than once, we hypothesize that the amount of these metabolites in the substrate may also change with the harvest cycles. A previous study has recovered EGT as a desirable product from mushroom waste [

29]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have systematically quantified the EGT content in SMS.

This study aims to analyze the potential bioactive compounds in SMS across different harvest cycles. By exploring the metabolites in SMS, this work contributes to the sustainable valorization of SMS and its potential applications.

4. Discussion

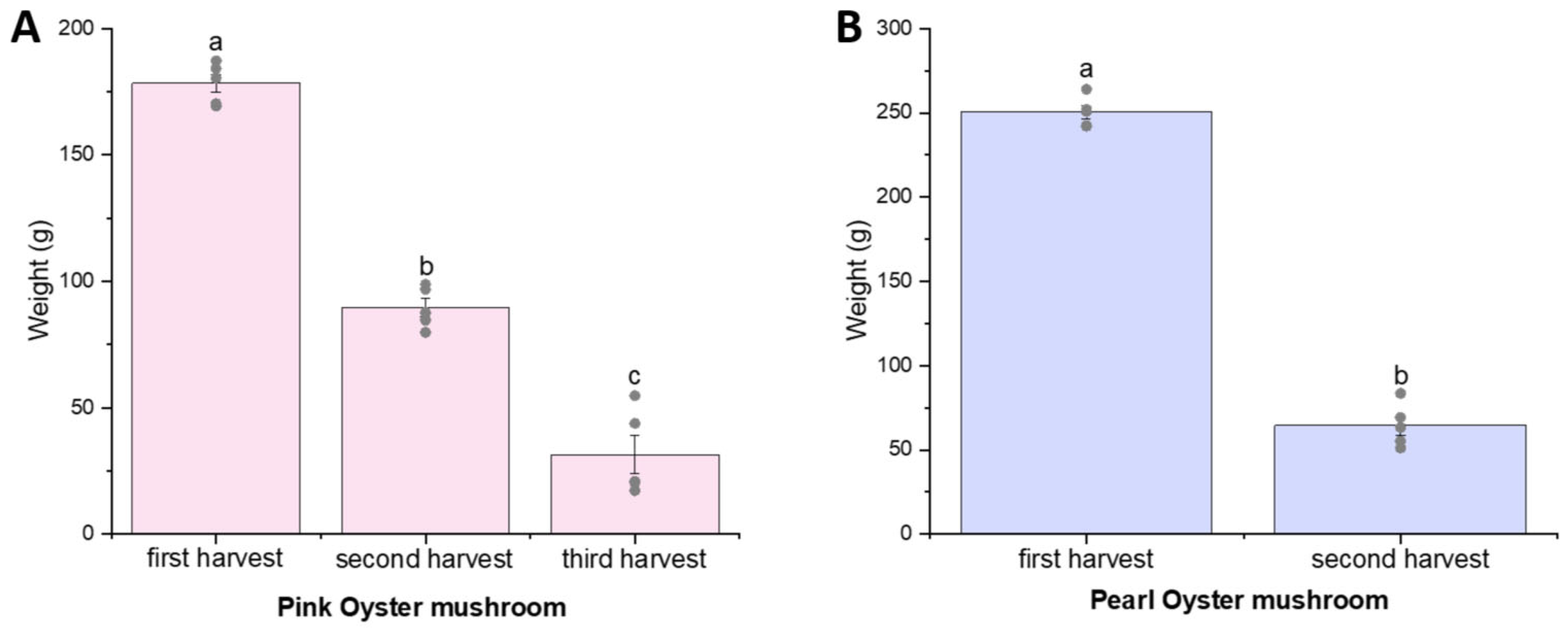

EGT and its related metabolites were quantified in mushroom fruiting bodies and SMS in this study. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to quantify the levels of EGT and related metabolites in SMS. There were variations in EGT content across different harvests cycles; however, no consistent pattern was identified. This may be due to differences in external factors such as environmental conditions or physiological stress responses, which may still be present in the experiment despite our best attempt at controlling their growth conditions.

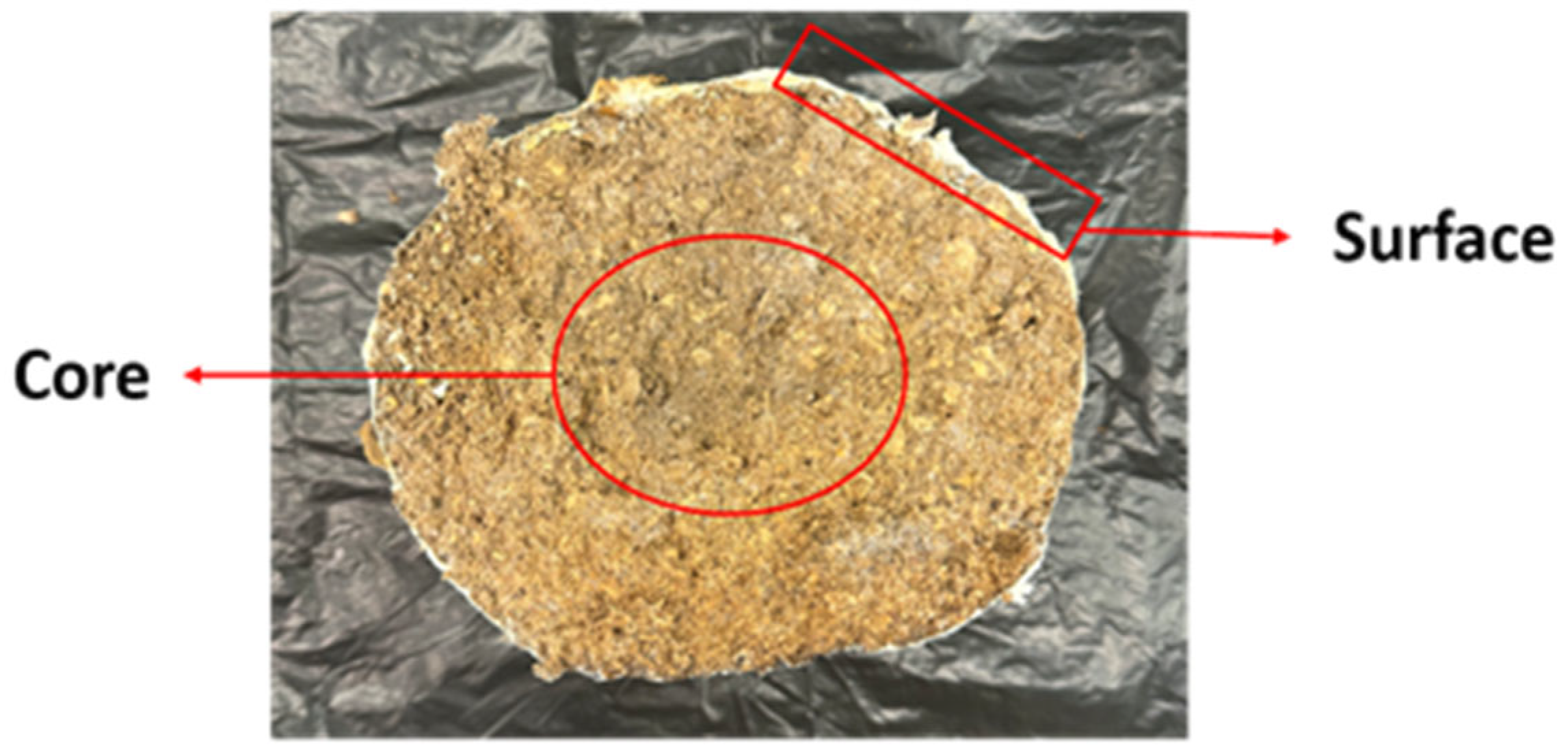

In this study, we also observed spatial complexity in SMS, with EGT and hercynine exhibiting higher levels in the surface substrate compared to the core substrate. Additionally, hercynine displayed divergent temporal trends between mushroom types. These patterns underscore the spatial and temporal complexity of metabolite dynamics within SMS.

Interestingly, while EGT was present in the unused substrate, ETSO3H and hercynine were not detectable in the unused substrates and were only present in the SMS. Their presence is likely a consequence of fungal metabolism. However, the potential health benefits of these compounds remain unexplored.

It has been suggested that SMS could serve as a potential source of antioxidants [

9]. However, we found no statistically significant enrichment of antioxidants in the SMSs compared to the unused substrates, which also aligns with our findings for EGT. One possible explanation is that mushrooms actively absorb antioxidant compounds or their precursors from the substrate during growth and retain them within their tissues. A previous study has shown that EGT biosynthesis in mushrooms such as

Flammulina velutipes is tightly regulated and depends on the uptake of specific amino acid precursors from the substrate, followed by intracellular synthesis and storage [

35]. Furthermore, analysis of post-harvest mushrooms has demonstrated that EGT is highly stable within fungal tissue and only degrades significantly under extreme heat or prolonged boiling, indicating that it is not readily secreted into the environment during cultivation [

36]. These findings support the view that EGT and other nutrients are efficiently sequestered in the fungal biomass and are minimally released into the SMS. In addition, variations reported in the literature regarding SMS antioxidant capacity likely stem from differences in fungal species, substrate formulations, and extraction solvent polarity, all of which can substantially influence TPC measurements across studies [

37,

38].

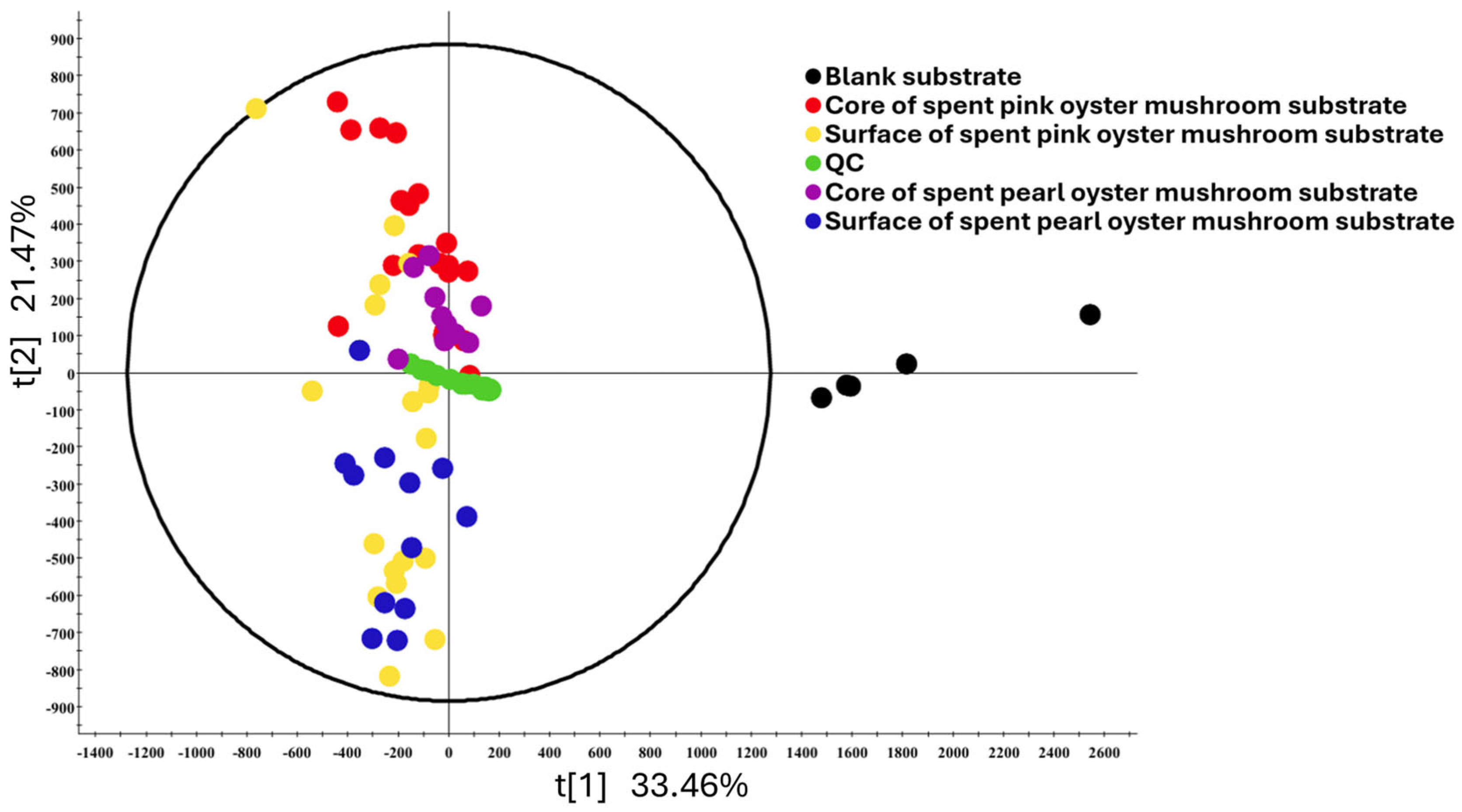

The PCA plot of the untargeted metabolome analysis (

Figure 3) revealed that the composition of SMS was easily distinguishable from unused substrates; however, there was significant overlap between SMSs from different sampling locations. We also conducted PCA based on the number of harvest cycles (

Supplementary Figure S1) and also found significant overlaps between samples from different harvest cycles. This indicates that mushroom cultivation by itself was the largest factor affecting changes in SMS composition. The number of harvest cycles and the location of the substrate played a less significant role. While counterintuitive, these results are expected. The growth cycle of cultivated mushrooms starts with the inoculation of the mycelium, which goes on to colonize the entire bag of substrates. After the entire bag of substrates has been colonized, fruiting is triggered by increasing exposure to oxygen. Hence, by the time the mushrooms and substrates are ready for collection, any growth and metabolite production in the spent substrate may have reached a steady state plateau [

39,

40].

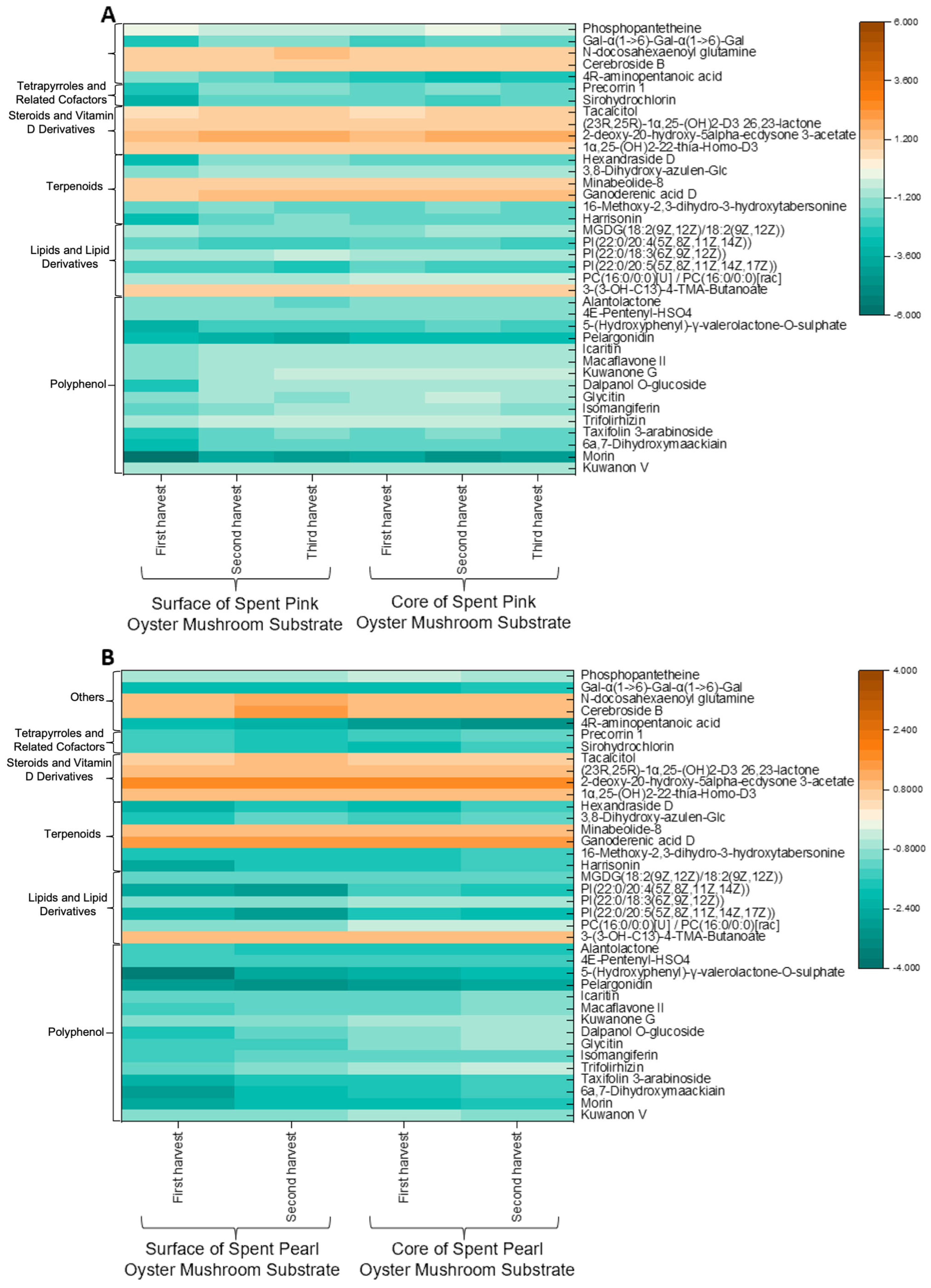

As illustrated in

Figure 5, most of the compounds detected, particularly the polyphenols, were present at lower concentrations in the SMS. This finding contradicts earlier reports that SMS could be a source of polyphenols [

9] but aligns with findings that mushrooms lack key the enzymes required for flavonoid biosynthesis [

41]. Given that mushrooms are unable to produce flavonoids, the decrease in polyphenols observed is most likely due to fungal degradation of the polyphenols originally present in the substrate. The levels of lipids and lipid derivatives were lower in the SMS compared to the unused substrate, which is consistent with the notion that fungi can assimilate exogenous lipids during growth [

42]. Tetrapyrroles, which play essential roles in light signaling, respiration, photosynthesis, and programmed cell death, also showed a decrease in abundance during mushroom cultivation [

43]. In contrast, terpenoid levels exhibited both increases and decreases. This variability may be attributed to their role as metabolites, which are not essential for primary growth and development but are instead involved in the plant’s defense against biotic and abiotic stresses [

44].

Despite SMS not being a rich source of EGT, our untargeted analysis highlighted other valuable bioactive compounds. One such compound is putatively identified as ganoderenic acid D, a triterpenoid known for its anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective effects [

45,

46]. While ganoderenic acids are most associated with

Ganoderma spp., they have also been recently reported in traditional Chinese medicine preparations [

47]. This study shows that SMS from

Pleurotus spp. may also contain ganoderenic acid D.

Several vitamin D-related derivatives were detected. Although ergocalciferol (vitamin D

2) itself was not observed, the presence of its metabolic products aligns with previous reports of mushrooms as a non-animal source of vitamin D [

3,

48]. It is plausible that most of the vitamin D may have been converted into these metabolites in the SMS but this would need to be further verified.

Cerebrosides are found across plants, fungi, and animals. They have been isolated from African medicinal plants and are known for their potent anti-inflammatory properties, along with weak antifungal and antimycobacterial activities, and have also been associated with improving the skin’s water-retention capacity [

49]. Minabeolide is commonly found in soft corals and has also been identified in

Withania aristate (Aiton) Pauquy, a medicinal plant endemic to the North African Sahara [

50]. It has demonstrated both cytotoxic activity against cancer cells and anti-inflammatory effects [

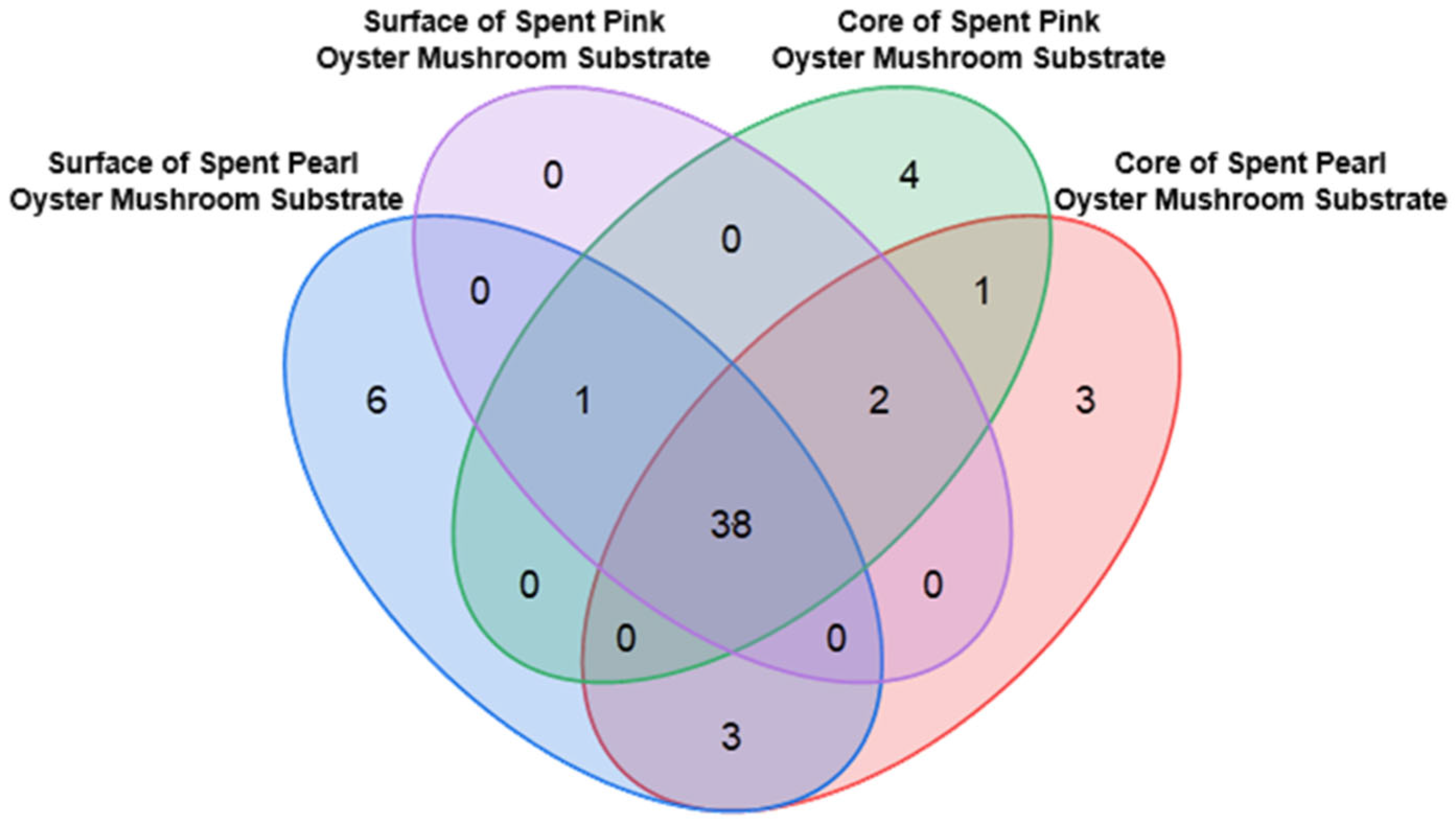

51]. The compounds that are unique to either the pink or pearl oyster SMS are shown in

Table S7, and some of them have potential health benefits. For instance, stachyose is a prebiotic oligosaccharide, supports beneficial gut microbiota, and may promote intestinal health [

52]. Phosphopantetheine is a prosthetic group for acyl carrier proteins in fatty acid biosynthesis, with potential antioxidant properties and anti-atherogenic roles [

53,

54]. Adenosine, involved in energy transfer and cellular signaling, may also enhance testicular activity and counteract fatigue [

55]. These compounds have demonstrated potential health benefits and may therefore warrant further analysis in SMS. Although SMS may not be suitable for nutraceutical recovery of EGT, it may serve as a low-cost source of potential bioactive compounds such as ganoderenic acid D and cerebroside B.

A key limitation of this study is that the metabolites annotations were assigned based solely on accurate mass and database matching without MS/MS spectral confirmation or validation with analytical standards. Further targeted analytical validation is required to verify that SMS is a source of these bioactive compounds.