Comparative Evaluation of the Texture, Taste, and Flavor of Different Varieties of White Radish: Relationship Between Substance Composition and Quality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

2.2. Sample and Treatment

2.3. Determination of Basic Indicators

2.4. Texture Analysis

2.5. Analysis of Pectin and Cellulose Substances Affecting Texture

2.6. Electronic Tongue Analysis

2.7. Total Sugar, Total Acid

2.8. Amino Acids

2.9. Electronic Nose Analysis

2.10. Headspace Gas Solid-Phase Microextraction (HS-SPME) and Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Basic Indicator Analysis

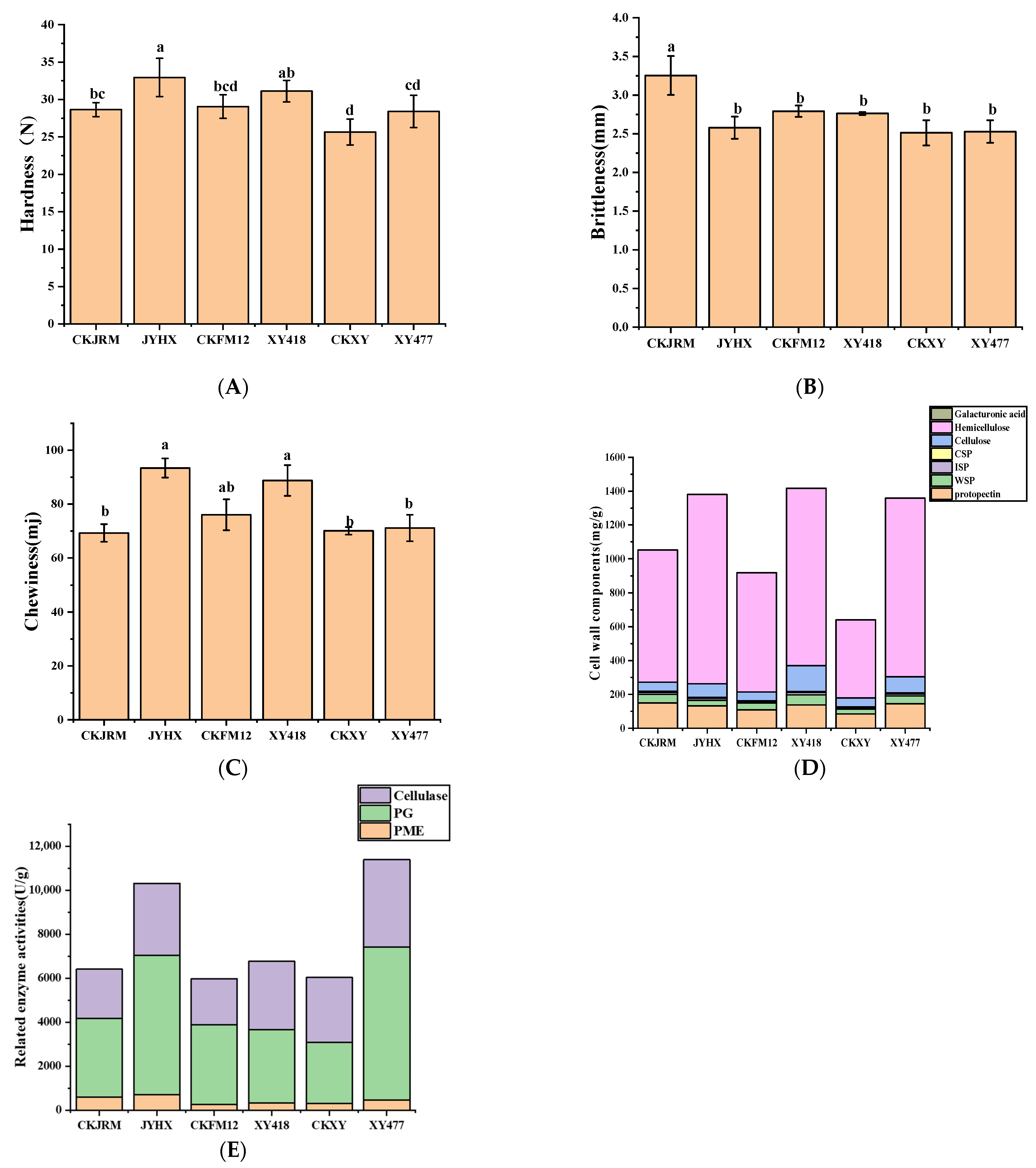

3.2. Analysis of Texture Characteristics

3.2.1. Texture

3.2.2. Analysis of Cell Wall Substances

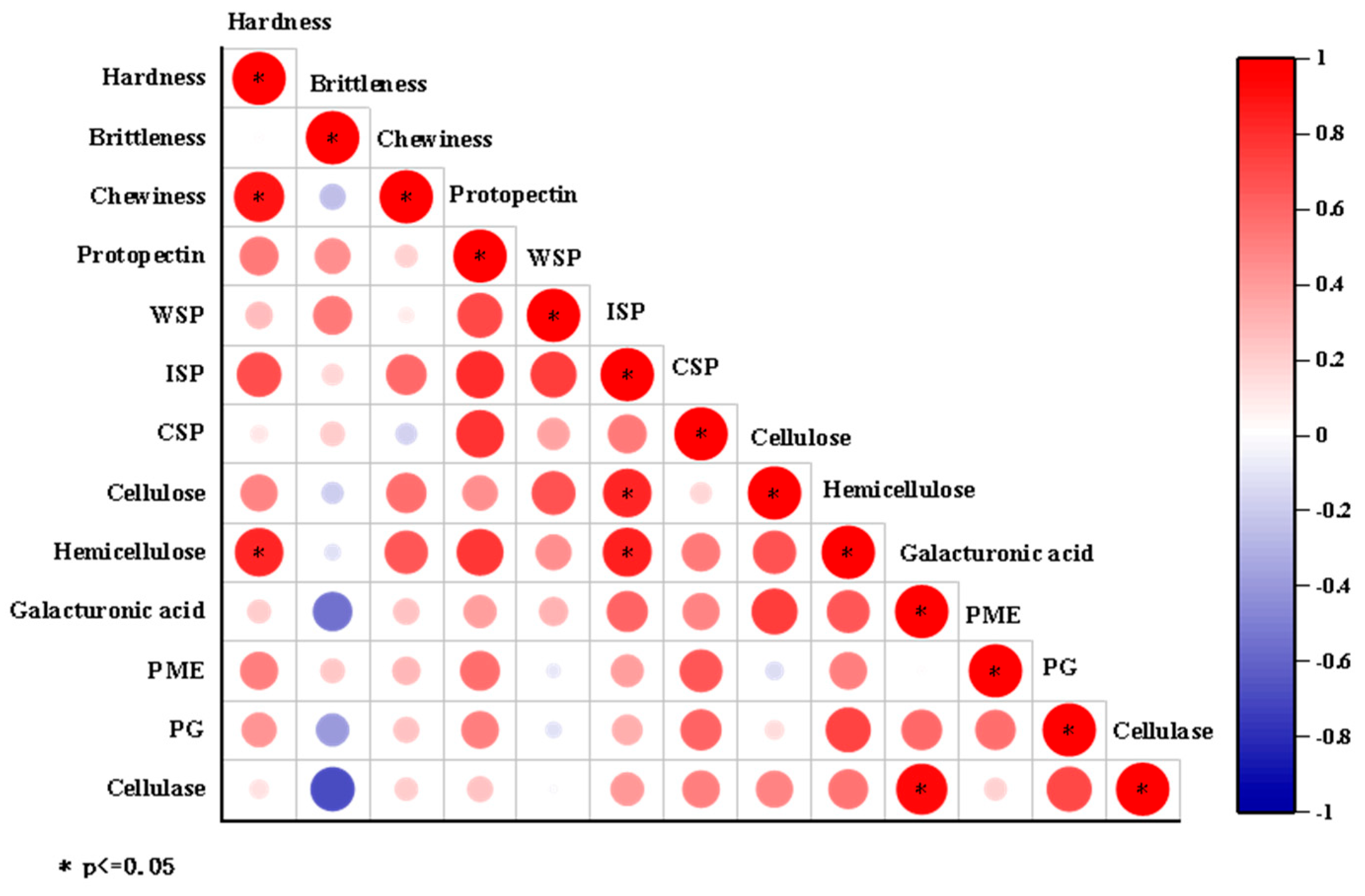

3.2.3. Correlation Analysis

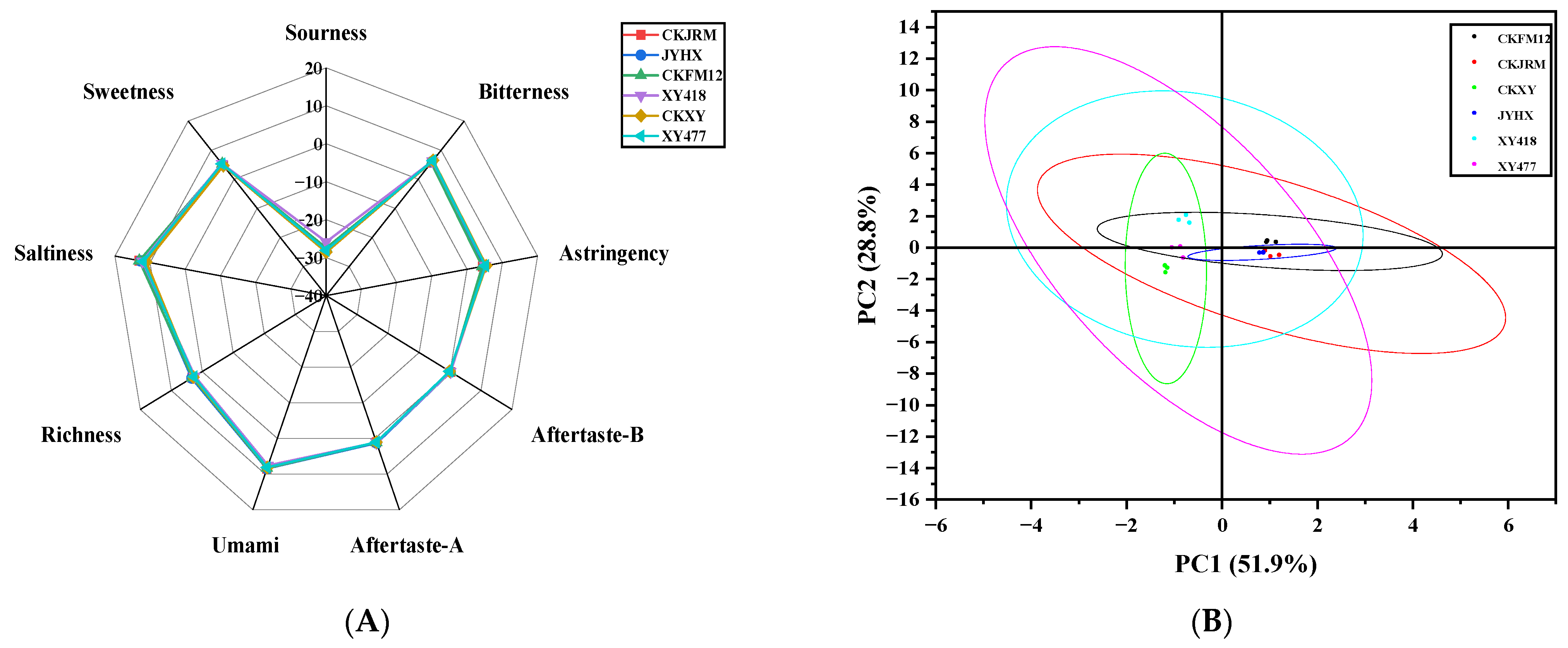

3.3. Taste Analysis

3.3.1. Electronic Tongue

3.3.2. Total Sugar and Total Acid

3.3.3. Amino Acids

3.4. Flavor Analysis

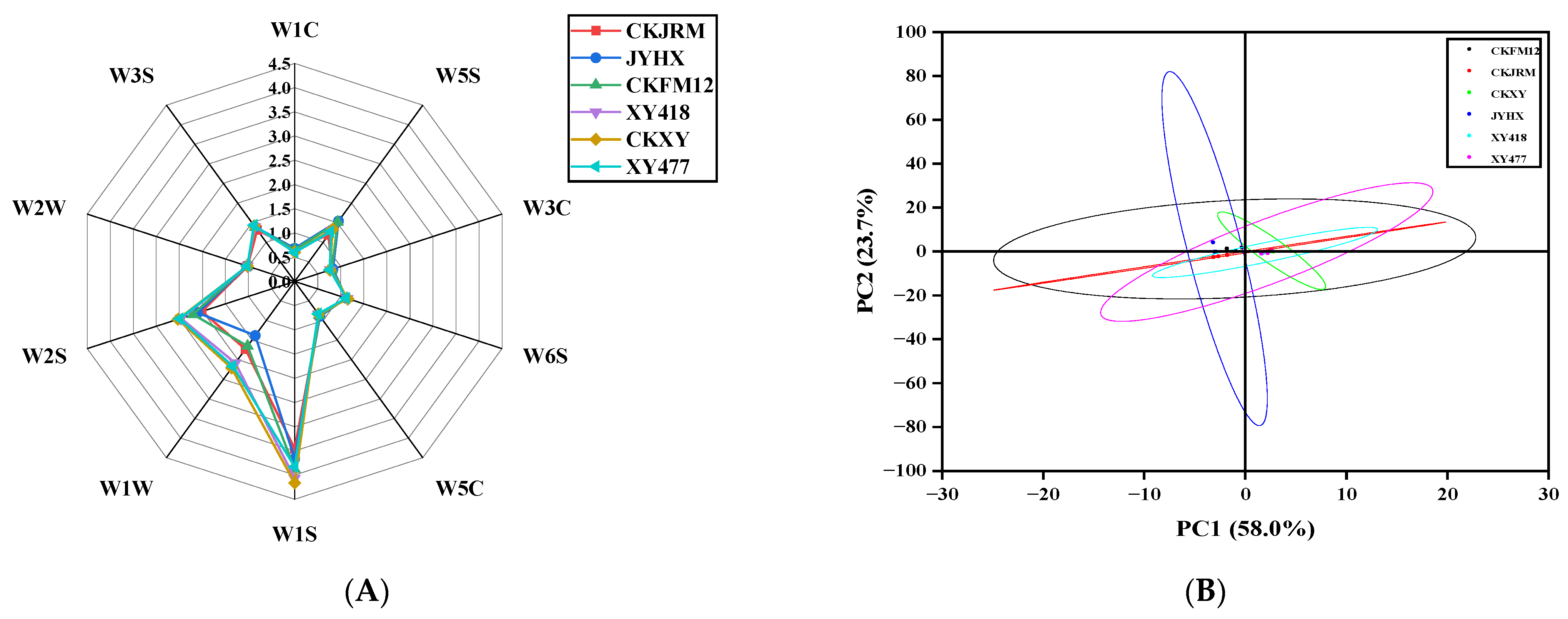

3.4.1. Electronic Nose

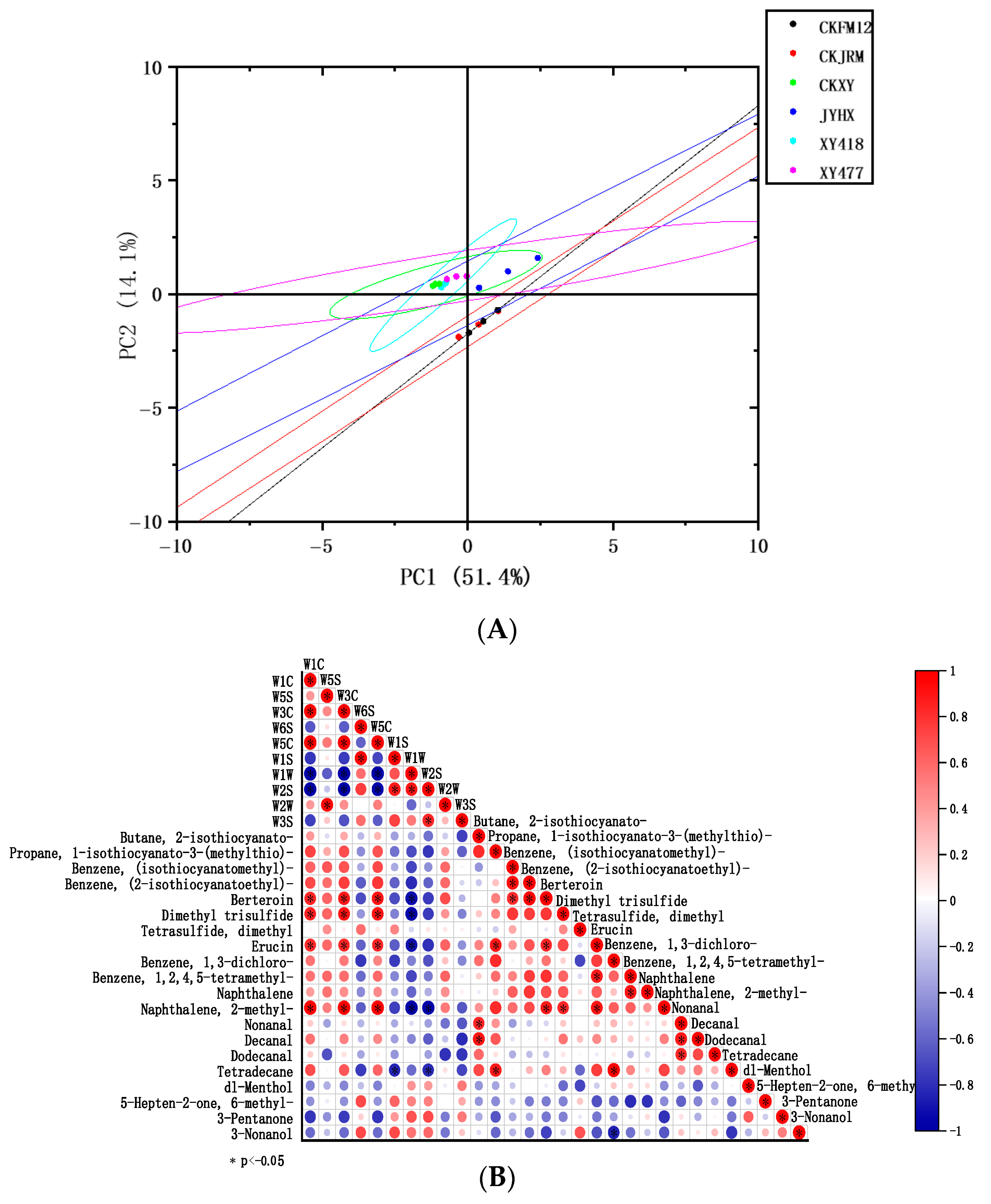

3.4.2. GC-MS

3.4.3. Correlation Analysis

3.5. Comprehensive Integration of Texture, Taste, and Flavor Profiles

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mei, S.Y.; He, Z.J.; Zhang, J.F. Identification and analysis of major flavor compounds in radish taproots by widely targeted metabolomics. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 889407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Xing, W.H.; Liu, Y.; Wan, Y.P.; Li, N.; Wang, J.Y.; Liu, G.Y.; Wang, R.; et al. Characterization of the volatile compounds in white radishes under different organic fertilizer treatments by HS-GC-IMS with PCA. Flavour Fragr. J. 2023, 38, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Dong, Y.J.; Wang, L.; Zhao, S.C. Integrated metabolomics and transcriptomics analysis provides insights into biosynthesis and accumulation of flavonoids and glucosinolates in different radish varieties. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2025, 10, 100938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.M.; Zhu, K.X.; Li, W.L.; Peng, Y.Q.; Yi, Y.W.; Qiao, M.F.; Fu, Y. Characterization of flavor and taste profile of different radish (Raphanus Sativus L.) varieties by headspace-gas chromatography-ion mobility spectrometry (GC/IMS) and E-nose/tongue. Food Chem. X 2024, 22, 101419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Yue, Y.L.; Pu, Y.A.; Yin, X.; Duan, Y.W.; Huang, A.X.; Yang, Y.Q.; Yang, Y.P. Expression profiles of glucosinolate biosynthetic genes in turnip (Brassica rapa var. rapa) at different developmental stages and effect of transformed flavin-containing monooxygenase genes on hairy root glucosinolate content. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 1064–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal, C.S.; Fredericks, D.P.; Griffiths, C.A.; Neale, A.D. The characterisation of AOP2: A gene associated with the biosynthesis of aliphatic alkenyl glucosinolates in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2010, 10, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, L.M.; Jepsen, H.S.K.; Halkier, B.A.; Kliebenstein, D.J.; Burow, M. Natural variation in cross-talk between glucosinolates and onset of flowering in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, M.; Hara, M.; Fukino, N.; Kakizaki, T.; Morimitsu, Y. Glucosinolate metabolism, functionality and breeding for the improvement of Brassicaceae vegetables. Breed. Sci. 2014, 64, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambiar, D.M.; Kumari, J.; Augustine, R.; Kumar, P.; Bajpai, P.K.; Bisht, N.C. GTR1 and GTR2 transporters differentially regulate tissue-specific glucosinolate contents and defence responses in the oilseed crop Brassica juncea. Plant Cell Environ. 2021, 44, 2729–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochevenko, A.; Fernie, A.R. The genetic architecture of branched-chain amino acid accumulation in tomato fruits. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 3895–3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigolashvili, T.; Yatusevich, R.; Berger, B.; Müller, C.; Flügge, U.I. The R2R3-MYB transcription factor HAG1/MYB28 is a regulator of methionine-derived glucosinolate biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 2007, 51, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, M.; Beyene, B.; Krumbein, A.; Stützel, H. Ontogenetic changes of 2-propenyl and 3-indolylmethyl glucosinolates in Brassica carinata leaves as affected by water supply. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 7259–7263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, F.; Zhou, H.S.; Hu, H.L.; Zhang, Y.T.; Ling, J.; Liu, X.S.; Luo, S.F.; Li, P.X. Green LED irradiation promotes the quality of cabbage through delaying senescence and regulating glucosinolate metabolism. Food Qual. Saf. 2024, 8, fyad041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.W.; Park, S.E.; Kim, E.J.; Seo, S.H.; Whon, T.W.; Son, H.S. Effects of ingredient size on microbial communities and metabolites of radish kimchi. Food Chem. X 2023, 20, 100950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viriyarattanasak, C.; Ando, Y.; Fukino, N.; Takemura, Y.; Hashimoto, T. The ability to resist freezing damage of three Japanese radish (Raphanus sativus L.) cultivars. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2023, 29, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.M.; Zhou, Q.; Li, D.; Wu, Y.P.; Zhong, K.; Gao, H. Effects of enhanced fermentation with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum WWPC on physicochemical characteristics and flavor profiles of radish paocai and dried-fermented radish. Food Biosci. 2024, 59, 103941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, T.; Wang, D.K.; Yao, S.J.; Yang, H.; Che, Y.L.; Wu, C.D. Effects of salt concentration on the quality and microbial diversity of spontaneously fermented radish paocai. Food Res. Int. 2022, 160, 111622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NY/T 1267-2007 ; Industry Standards for Radishes. Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2007.

- Yue, W.; Li, Z.D.; Wang, D.; Wang, P.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, X.Y.; Zhao, W.T. Correlation of physicochemical properties and volatile profiles with microbiome diversity in cucumber during lightly-pickling in seasoning liquid. Food Chem. 2025, 483, 144294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.W.; Yan, X.W.; Wang, P.W.; Liu, Z.Y.; Sun, L.; Li, X.Z. Changes in fruit texture and cell structure of different pumpkin varieties (lines) during storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2024, 208, 112647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.J.; Jo, S.M.; Yoon, S.; Jeong, H.; Lee, Y.; Park, S.S.; Shin, E.C. Analysis of volatile and non-volatile compound profiles of wintering radish produced in Jeju-island by different oven roasting temperatures and times using electronic nose and electronic tongue techniques via multivariate analysis. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 32, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 12456-2021; National Food Safety Standard—Determination of Total Acid in Foods. National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China, State Administration for Market Regulation: Beijing, China, 2021.

- GB 5009.124-2016; National Food Safety Standard—Determination of Amino Acids in Foods. The National Health and Family Planning Commission of the People’s Republic of China and the China Food and Drug Administration: Beijing, China, 2016.

- Li, X.Q.; Liu, D.Q. Nutritional content dynamics and correlation of bacterial communities and metabolites in fermented pickled radishes supplemented with wheat bran. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 840641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Q.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, S.; Wang, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, D. Comparison between vacuum and modified-atmosphere packaging on dynamic analysis of flavor properties and microbial communities in fresh-cut potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.). Food Packag. Shelf Life 2023, 39, 101149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.Y.; Zhang, J.M.; Zhang, C.C.; Xin, X.T.; Liu, D.Q. Halophilic microbes and mineral compositions in salts associated to fermentation and quality of fermented radish. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 193, 115746. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.L.; Zhang, L.Y.; Wu, D.R.; Lin, S.; Xie, J.X.; Li, J. Analysis of changes in volatile metabolites of pickled radish in different years using GC-MS, OAV and multivariate statistics. Food Chem. 2025, 478, 143760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Jia, Z.L.; Zhou, H.L.; Zhang, D.; Li, G.C.; Yu, J.H. Comparative analysis of volatile compounds from four radish microgreen cultivars based on ultrasonic cell disruption and HS-SPME/GC-MS. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Yi, R.; Yue, T.; Bi, X.; Wu, L.; Pan, H.; Liu, X.; Che, Z. Effect of dense phase carbon dioxide treatment on the flavor, texture, and quality changes in new-paocai. Food Res. Int. 2023, 165, 112431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Jia, Y.; Li, Y.; Jiao, X.; He, Y.; Wen, L.; Wang, Z. Comprehensive impact of pre-treatment methods on white radish quality, water migration, and microstructure. Food Chem. X 2024, 24, 101991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Li, L.; Cao, R.X.; Xu, S.; Cheng, L.L.; Yu, M.Y.; Lv, Z.F.; Lu, G.Q. Changes in cell wall components and polysaccharide-degrading enzymes in relation to differences in texture during sweetpotato storage root growth. J. Plant Physiol. 2020, 254, 153282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Q.Q.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, W.T.; Wang, P.; Qin, P.Y.; Wang, J.J.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Ge, Z.W.; Zhao, X.Y.; Wang, D. The role of water distribution, cell wall polysaccharides, and microstructure on radish (Raphanus sativus L.) textural properties during dry-salting process. Food Chem. X 2024, 22, 101407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.H.; Shi, X.J.; Liu, X.M.; Srivastava, A.K.; Shi, X.J.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Hu, C.X.; Zhang, F.S. Calcium application regulates fruit cracking by cross-linking of fruit peel pectin during young fruit growth stage of citrus. Sci. Hortic. 2025, 340, 113922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Li, Y.F.; Yan, L.P.; Xie, J. Effect of edible coatings on enzymes, cell-membrane integrity, and cell-wall constituents in relation to brittleness and firmness of Huanghua pears (Pyrus pyrifolia Nakai, cv. Huanghua) during storage. Food Chem. 2011, 124, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Song, Y.Q.; Zhang, X.J.; Pan, L.Q.; Tu, K. Calcium absorption in asparagus during thermal processing: Different forms of calcium ion and cell integrity in relation to texture. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 111, 889–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Park, Y.B.; Cosgrove, D.J.; Hong, M. Cellulose-Pectin Spatial Contacts Are Inherent to Never-Dried Arabidopsis Primary Cell Walls: Evidence from Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Plant Physiol. 2015, 168, 871–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Ye, J.F.; Zhou, L.Y.; Chen, M.J.; Wei, Y.Y.; Jiang, S.; Chen, Y.; Shao, X.F. Cell wall metabolism during the growth of peach fruit: Association of hardness with cell wall pectins. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 330, 113058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.L.; Zhang, L.Y.; Karrar, E.; Wu, D.R.; Chen, C.X.; Zhang, Z.X.; Li, J. A cooperative combination of non-targeted metabolomics and electronic tongue evaluation reveals the dynamic changes in metabolites and sensory quality of radish during pickling. Food Chem. 2024, 446, 138886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, W.; Kobayashi, T.; Takahashi, A.; Kumakura, K.; Matsuoka, H. Metabolism of glutamic acid to alanine, proline, and γ-aminobutyric acid during takuan-zuke processing of radish root. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Chen, G.; Wang, D.D.; Hu, R.; Li, H.; Liu, S.L.; Zhang, Q.S.; Ming, J.Y.; Chi, Y.L. Effects of dry-salting and brine-pickling processes on the physicochemical properties, nonvolatile flavour profiles and bacterial community during the fermentation of Chinese salted radishes. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 157, 113084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.R.; Li, Y.X.; Zhao, Y.R.; Guan, H.; Jin, C.W.; Gong, H.S.; Sun, X.M.; Wang, P.; Li, H.M.; Liu, W.L. Effect of Levilactobacillus brevis as a starter on the flavor quality of radish paocai. Food Res. Int. 2023, 168, 112780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, G.J.; Kim, D.W.; Gu, E.J.; Song, S.H.; Lee, J.I.; Lee, S.B.; Kim, J.H.; Ham, K.S.; Kim, H.J. GC/MS-based metabolomic analysis of the radish water kimchi, Dongchimi, with different salts. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2015, 24, 1967–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, Y.; Tao, Y.; Chen, X.; She, X.; Qian, Y.; Li, Y.; Du, Y.; Xiang, W.; Li, H.; Liu, L. The characteristics and correlation of the microbial communities and flavors in traditionally pickled radishes. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 118, 108804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baky, M.H.; Shamma, S.N.; Xiao, J.; Farag, M.A. Comparative aroma and nutrients profiling in six edible versus nonedible cruciferous vegetables using MS based metabolomics. Food Chem. 2022, 383, 132374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, R.; Fan, A.P.; Hu, X.S.; Liao, X.J.; Chen, F. Effects of high pressure processing on the quality of pickled radish during refrigerated storage. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2016, 38, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.J.; Boo, C.G.; Lee, J.; Hur, S.W.; Jo, S.M.; Jeong, H.; Yoon, S.; Lee, Y.; Park, S.S.; Shin, E.C. Chemosensory approach supported-analysis of wintering radishes produced in Jeju island by different processing methods. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 30, 1033–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Moisture (%) | PH | Brix Degrees (%) | Vitamin C (mg/g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CKJRM | 92.05 ± 0.01 ab | 5.22 ± 0.02 d | 3.9 ± 0.1 e | 0.46 ± 0.01 d |

| JYHX | 92.02 ± 1.55 ab | 5.4 ± 0.01 b | 4.1 ± 0.2 de | 0.87 ± 0.02 a |

| CKFM12 | 89.96 ± 0.34 b | 5.04 ± 0.01 f | 5.13 ± 0.06 a | 0.58 ± 0.02 b |

| XY418 | 92.36 ± 0.09 a | 5.73 ± 0.02 a | 4.53 ± 0.06 b | 0.39 ± 0.03 e |

| CKXY | 90.49 ± 1.41 ab | 5.15 ± 0.01 e | 4.3 ± 0.1 cd | 0.53 ± 0.03 c |

| XY477 | 90.36 ± 0.17 ab | 5.3 ± 0.01 c | 4.43 ± 0.12 bc | 0.58 ± 0.03 b |

| Compound Name | Odor Description | Threshold (mg/kg) | OAV of VOCs in the Sample | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CKJRM | JYHX | CKFM12 | XY418 | CKXY | XY477 | |||

| Butane, 2-isothiocyanato- | green | 0.09 | 0.044 | ND | 0.044 | 0.022 | ND | ND |

| Propane, 1-isothiocyanato-3-(methylthio)- | sulfurous | 0.65 | 0.571 | 0.415 | 0.728 | 0.248 | 0.212 | 0.255 |

| Benzene, (isothiocyanatomethyl)- | spicy, oily | 0.007 | ND | 0.143 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Benzene, (2-isothiocyanatoethyl)- | green | 0.24 | 0.508 | 1.158 | 0.500 | 0.313 | 0.192 | 0.554 |

| Berteroin | cabbage, radish | 0.8 | 0.399 | 0.804 | 0.453 | 0.085 | 0.08 | 0.321 |

| Dimethyl trisulfide | sulfureous | 0.0001 | 820 | 1070 | 840 | 800 | 600 | 570 |

| Tetrasulfide, dimethyl | garlic, meaty | 0.00002 | 1800 | 2700 | 2250 | 2950 | 2550 | 1450 |

| Erucin | cabbage, radish | 0.0032 | 854.063 | 1018.438 | 1135.000 | 561.25 | 368.438 | 654.063 |

| Benzene, 1,3-dichloro- | sweet | 0.17 | 0.024 | 0.012 | 0.024 | ND | ND | 0.018 |

| Benzene, 1,2,4,5-tetramethyl- | rancid, sweet | 0.061 | 0.049 | 0.082 | 0.082 | 0.049 | 0.016 | 0.066 |

| Naphthalene | Pungent, dry | 0.006 | 0.5 | 0.833 | 0.667 | 0.667 | 0.333 | 0.667 |

| Naphthalene, 2-methyl- | oily, aromatic | 0.003 | 1.333 | 1.667 | 1.333 | ND | ND | ND |

| Nonanal | rose, fatty | 0.0011 | 15.455 | 8.182 | 12.727 | 15.455 | 6.364 | 9.091 |

| Decanal | fatty | 0.003 | 6.333 | 4 | 5.667 | 5.667 | 2.667 | 2 |

| Dodecanal | soapy, waxy | 0.0002 | 15 | ND | ND | 10 | ND | ND |

| Tetradecane | mild, waxy | 1 | 1.667 | 0.667 | 1.333 | ND | ND | 0.667 |

| dl-Menthol | peppermint, cool, woody | 0.13 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.046 |

| 5-Hepten-2-one, 6-methyl- | green, apple, banana | 0.068 | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.029 | ND |

| 3-Pentanone | ethereal, acetone | 0.06 | 0.067 | 0.067 | 0.067 | 0.167 | 0.083 | 0.167 |

| 3-Nonanol | spice, herbal, oily | 0.07 | ND | ND | ND | 0.029 | 0.014 | ND |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cai, X.; Hou, W.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Q.; Liu, T.; Zhao, X.; Wang, D. Comparative Evaluation of the Texture, Taste, and Flavor of Different Varieties of White Radish: Relationship Between Substance Composition and Quality. Foods 2026, 15, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010103

Cai X, Hou W, Zhang L, Wang Q, Liu T, Zhao X, Wang D. Comparative Evaluation of the Texture, Taste, and Flavor of Different Varieties of White Radish: Relationship Between Substance Composition and Quality. Foods. 2026; 15(1):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010103

Chicago/Turabian StyleCai, Xinzhu, Wanfu Hou, Li Zhang, Qingbiao Wang, Tianran Liu, Xiaoyan Zhao, and Dan Wang. 2026. "Comparative Evaluation of the Texture, Taste, and Flavor of Different Varieties of White Radish: Relationship Between Substance Composition and Quality" Foods 15, no. 1: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010103

APA StyleCai, X., Hou, W., Zhang, L., Wang, Q., Liu, T., Zhao, X., & Wang, D. (2026). Comparative Evaluation of the Texture, Taste, and Flavor of Different Varieties of White Radish: Relationship Between Substance Composition and Quality. Foods, 15(1), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods15010103