Assessment of Food Safety Knowledge and Practices Among Medical Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Hypotheses

1.2. The Aim of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Survey Questionnaire

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical Approval

3. Results

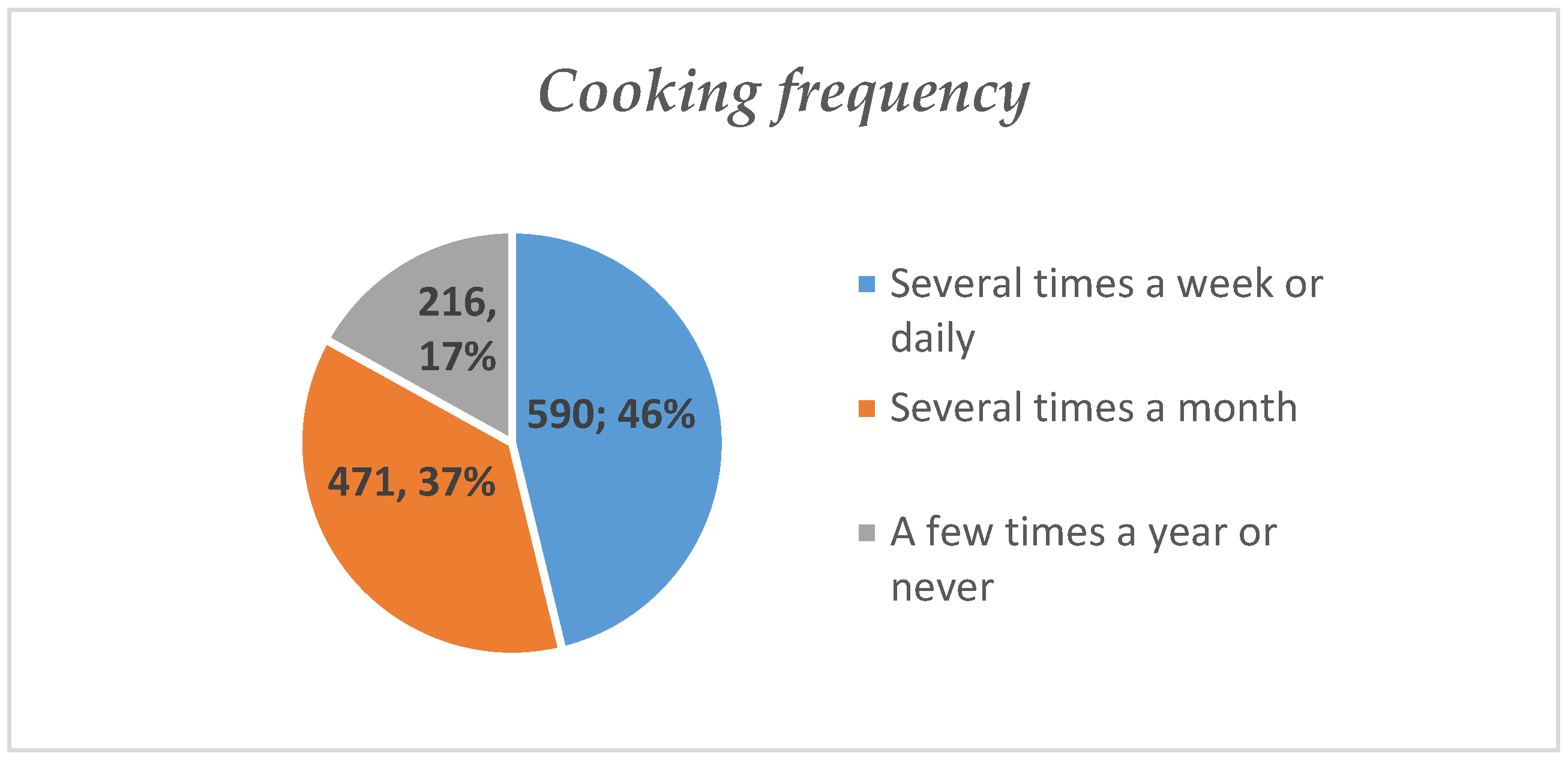

3.1. Respondents’ Eating Behaviors and Determinants of Food Choices

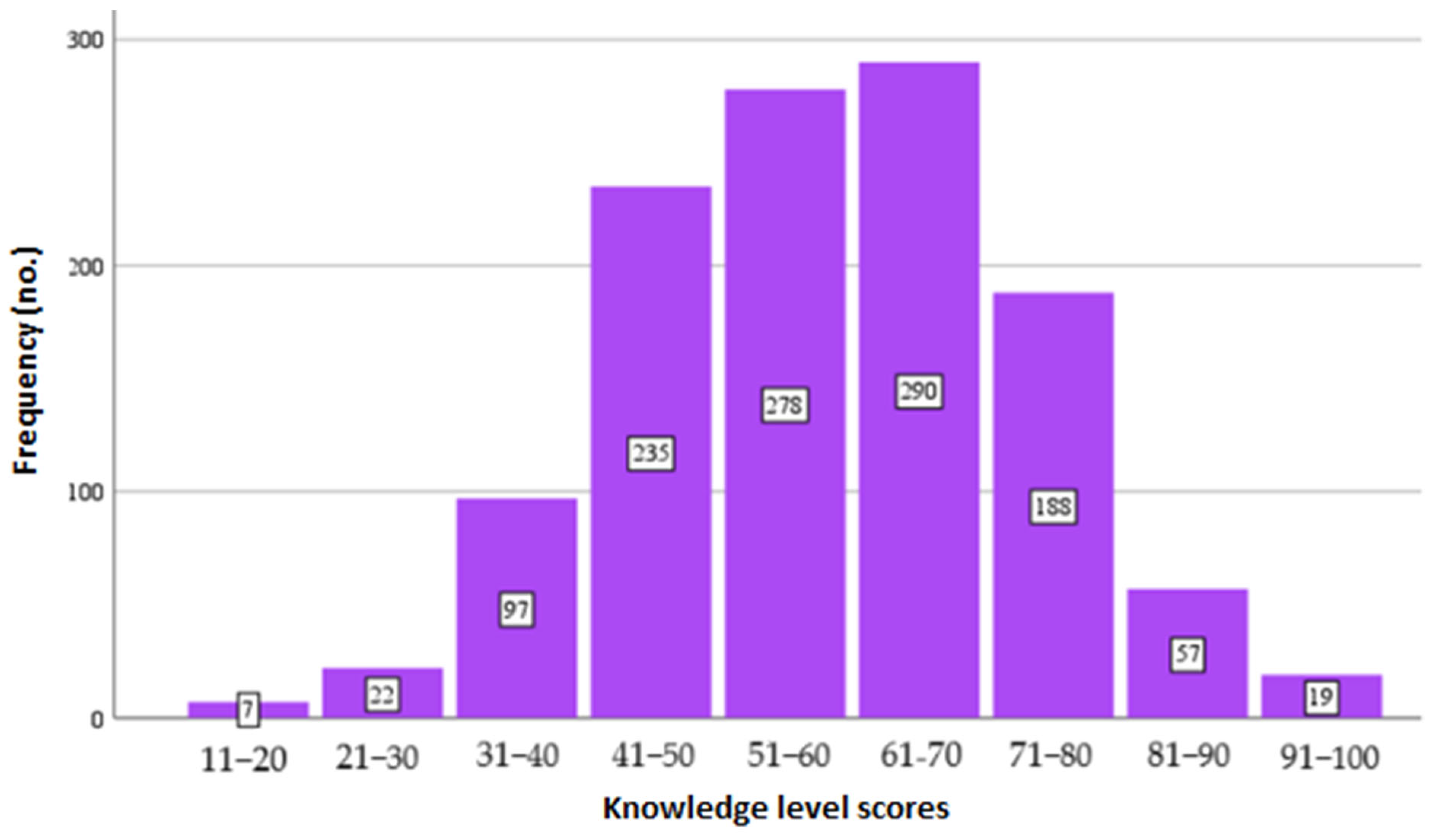

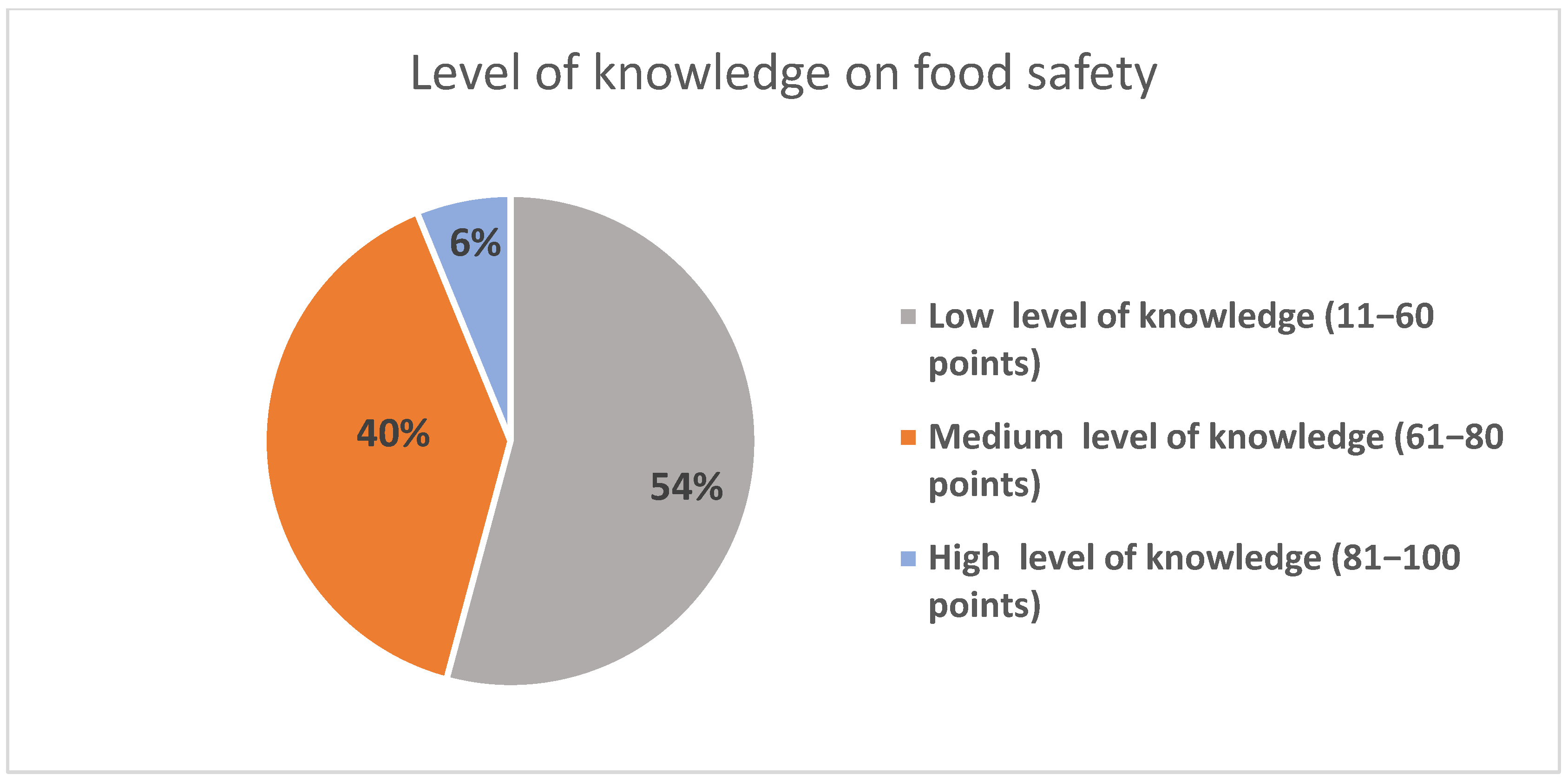

3.2. Respondents’ Assessment of Food Safety Knowledge

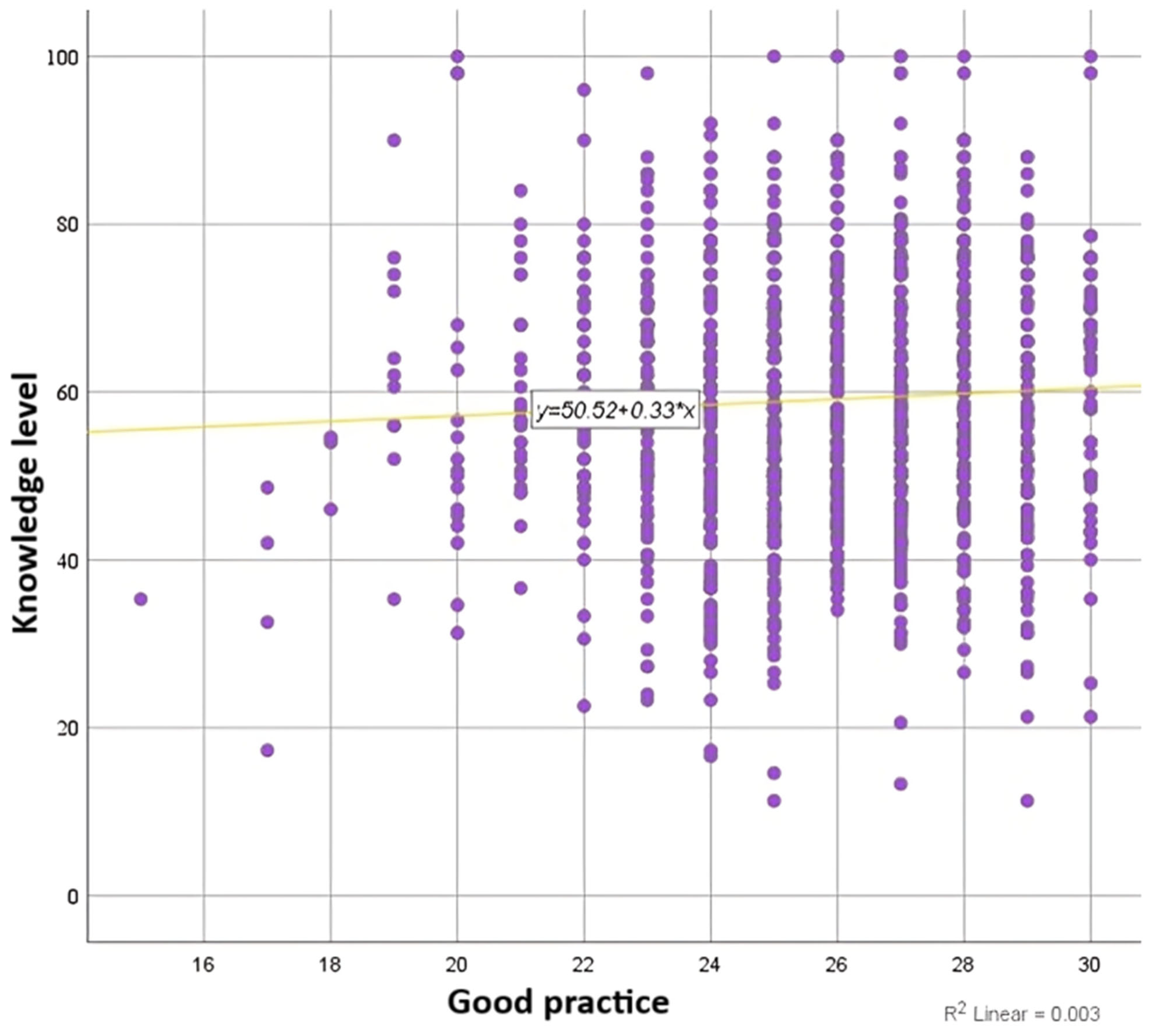

3.3. Results of the Analysis on Possible Correlations Between Participants’ Knowledge Level, Socio-Demographic Characteristics, and Eating Behavior

3.4. Respondents’ Assessment of Food Safety Practices

- -

- “Not to consume thermally prepared foods that have been at room temperature for more than 2 h”, which only a small proportion of respondents, 191 students (15%), respected;

- -

- “Not washing eggs until their use”, reported by 532 respondents (41%).

- -

- “Washing fruits and vegetables before eating”, reported by 1230 respondents (96%);

- -

- “Washing hands with soap and water before preparing food”, a response given by 1210 respondents (95%).

4. Discussion

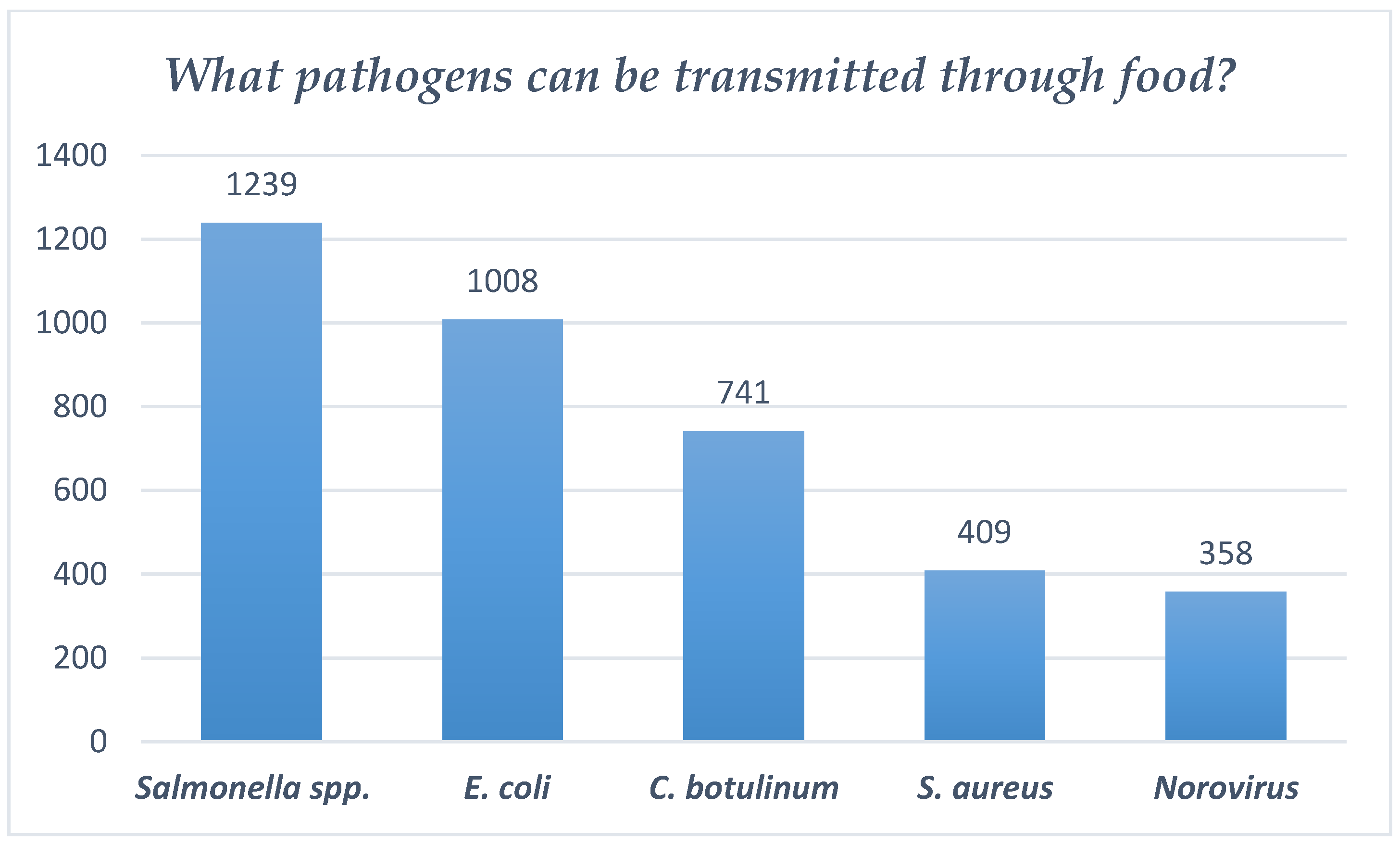

- Regarding the risk of E. coli infection through consumption of unwashed fruit and vegetables, 1009 respondents (79%) are aware of the possibility of the presence of pathogen agents on the food. The vast majority of respondents, 1226 (96%), confirmed that they wash fruit and vegetables every time before eating.

- However, as regards the risk of Salmonella infection, the vast majority of respondents, 1239 subjects (97%), are aware of the possibility of Salmonella on food; however, only about one third of the respondents, 383 subjects (30%), wash eggshells each time before using them in food preparation. Salmonella represents the most common cause of foodborne outbreaks in the European Union [46,47,48], and the most frequently contaminated food products in the region are egg products [49].

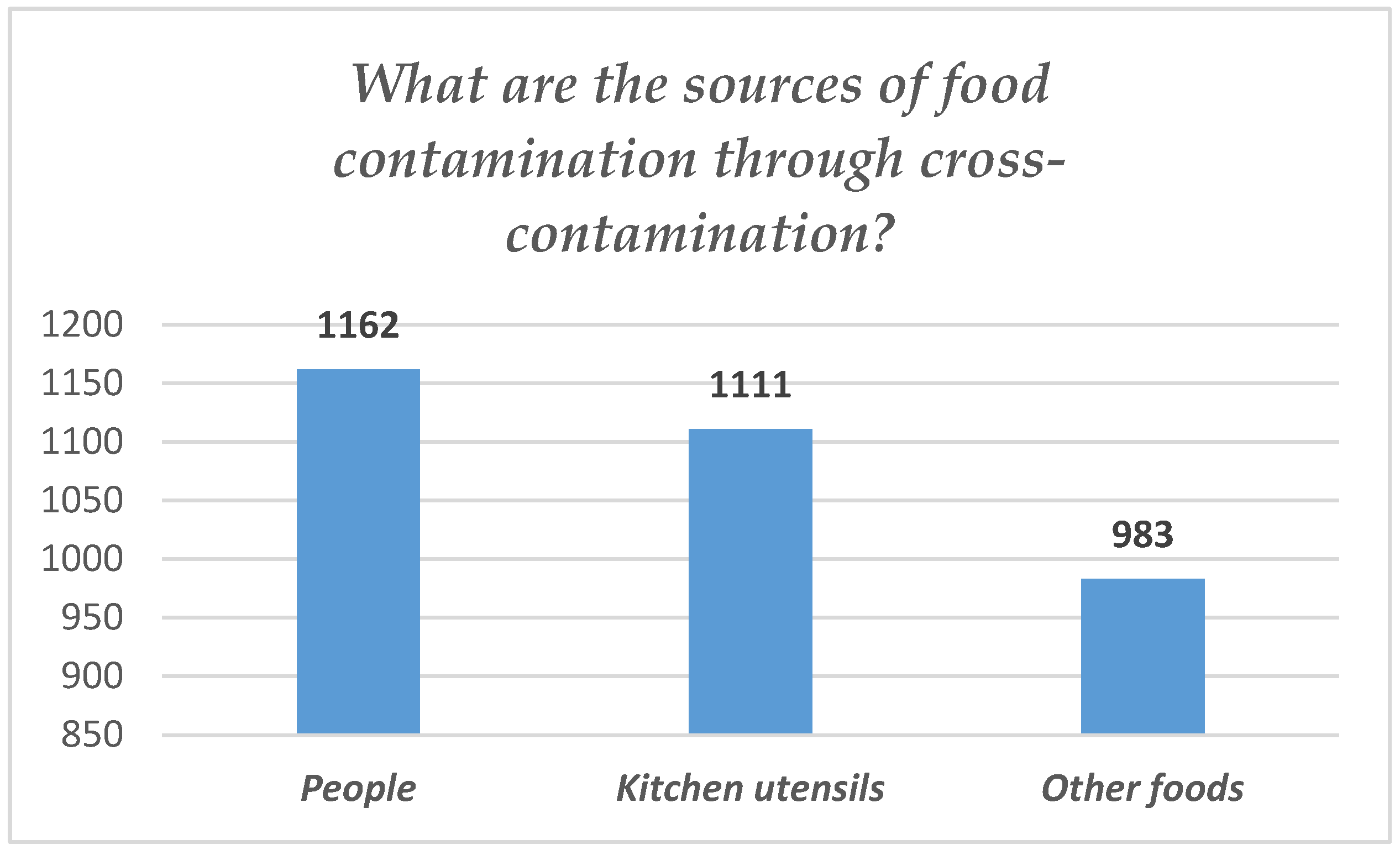

- Data collected about cross-contamination, caused by the person cooking the food touching more than one surface and the food with their own hands, showed that the majority of respondents, 1213 (95%), wash their hands every time before starting to prepare food. Also, a significant number of medical students participating in the study, 1137 subjects (89%), wash their hands every time after handling raw meat (pork, chicken, poultry), and a significant number of respondents, 1047 (82%), wash their hands every time after food preparation. Also, 230 respondents (18%) do not wash their hands after cooking. Of all respondents, 830 (65%) indicated being aware of cross-contamination danger.

- About half of the survey respondents, 690 subjects (54%), indicated knowing the optimal storage range for perishable foods in the refrigerator. However, 1137 respondents (89%) answered that they read the “use by” date on the food labels and respect it.

- Less than half of the participants, 575 medical students (45% of the total number of respondents), stated that they know the maximum time to keep thermally prepared food out of the refrigerator at room temperature to avoid contamination. Out of the total number of respondents, only 192 subjects (15%) respect the optimal time (2 h) of keeping thermally prepared food outside the refrigerator; the remaining respondents—1085 (85%)—do not respect the optimal time and eat the food even after it has been left for longer at room temperature (more than 2 h). In terms of food storage and the benefits of storing food in a refrigerator, 856 students (67%) answered correctly and knew that pathogens are not inactivated/eliminated by storing food in the refrigerator and that this can encourage stagnation or their multiplication in food. A total of 677 respondents (53%) answered that they read the information on food packaging about storage conditions to properly manage food and refrigeration.

- Of the total number of respondents, 55% of them (702 students) seemed to be aware of all prevention methods of food contamination. However, only 792 students (62%) remove their accessories (rings and bracelets) before food preparation begins. Thus, a significant number of respondents, 472 (37%), are exposed to the risk of food contamination through accessories worn during the cooking process. Jewelry hides dirt and bacteria, and can represent a risk of physical and chemical hazards. For this reason, food handlers should not wear rings, earrings, or watches [50].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Food Safety Factsheet. 4 October 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/food-safety (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Fung, F.; Wang, H.-S.; Menon, S. Food safety in the 21st century. Biomed. J. 2018, 41, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. A Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally Friendly Food System. 2020. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/horizontal-topics/farm-fork-strategy_en (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020. Transforming Food Systems for Affordable Healthy Diets; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, X.; Rui Wang, R.; Min, J. Analysis and Recognition of Food Safety Problems in Online Ordering Based on Reviews Text Mining. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 2022, 209732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Guttieres, D.; Levi, R.; Paulson, E.; Perakis, G.; Renegar, N.; Springs, S. Public health risks arising from food supply chains: Challenges and opportunities. Nav. Res. Logist. 2021, 68, 1098–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsey, J.; Ng, S.; Rowland, P.; Freeman, R.; Li, C.; Woods, N.N. The Basic Science of Patient-Physician Communication: A Critical Scoping Review. Acad. Med. 2021, 96, S109–S118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Zhang, Q.; Le, L.H.; Wu, Y. Physician Empathy in Doctor-Patient Communication: A Systematic Review. Health Commun. 2024, 39, 1027–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghafari, W.T.; Arfaoui, L. Food safety and hygiene education improves the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of Saudi dietetics students. Bioinformation 2022, 18, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Keczeli, V.; Kóró, M.; Tóth, V.; Csákvári, T.; Tisza, B.B.; Szántóri, P.; Asztalos, Á.C.; Verzár, Z.; Kisbenedek, A.G. Food Safety and Food Hygiene Knowledge of Hungarian University Students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuksanović, N.; Demirović Bajrami, D.; Petrović, M.D.; Jotanović Raletić, S.; Radivojević, G. Knowledge About Food Safety and Handling Practices—Lessons from the Serbian Public Universities. Zdr. Varst. 2022, 61, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahmy, E.; Ragab, H.; Abd el-Sattar, E. Food Safety Knowledge and Handling Practice among Medical Students at Zagazig University. Zagazig Univ. Med. J. 2024, 30, 3864–3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Chen, S. Research on online public opinion dissemination and emergency countermeasures of food safety in universities-take the rat head and duck neck incident in China as an example. Front. Public Health 2024, 11, 1346577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Luo, X.; Xu, X.; Shi, Z.; Reis, C.; Sharma, M.; Hou, X.; Zhao, Y. Effect of WeChat-based intervention on food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices among university students in Chongqing, China: A quasi-experimental study. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2023, 42, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halwani, M. A Study to Assess Basic Food Safety Knowledge among University Students. Food Nutr. Sci. 2023, 14, 526–541. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X.; Xu, X.; Chen, H.; Bai, R.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, Y.; Sharma, M.; Zeng, H.; et al. Food safety related knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) among the students from nursing, education and medical college in Chongqing, China. Food Control 2019, 95, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, M.S.; Susanna, D. Food safety knowledge, attitudes, and practices of food handlers at kitchen premises in the Port ’X’ area, North Jakarta, Indonesia 2018. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2021, 10, 9215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marklinder, I.; Wersén, V.; James, K. Food safety and healthcare professionals: The need for education and research. Food Control 2025, 171, 111118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guennouni, M.; Admou, B.; Bourrhouat, A.; El Khoudri, N.; Zkhiri, W.; Talha, I.; Hazime, R.; Hilali, A. Knowledge and Practices of Food Safety among Health Care Professionals and Handlers Working in the Kitchen of a Moroccan University Hospital. J. Food Prot. 2022, 85, 676–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stratev, D.; Odeyemi, O.A.; Pavlov, A.; Kyuchukova, R.; Fatehi, F.; Bamidele, F.A. Food safety knowledge and hygiene practices among veterinary medicine students at Trakia University, Bulgaria. J. Infect. Public Health 2017, 10, 778–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azanaw, J.; Dagne, H.; Andualem, Z.; Adane, T. Food Safety Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of College Students, Ethiopia, 2019: A Cross-Sectional Study. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 6686392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkistanl, T.T.; Sevgili, C. Food hygiene knowledge and awareness among undergraduate maritime students. Int. Marit. Health 2018, 69, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.N.; Hassan, H.F.; Amin, M.B.; Madilo, F.K.; Rahman, M.A.; Haque, M.R.; Aktarujjaman, M.; Farjana, N.; Roy, N. Food safety and handling knowledge and practices among university students of Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garayoa, R.; Córdoba, M.; García-Jalón, I.; Sanchez-Villegas, A.; Vitas, A.I. Relationship between consumer food safety knowledge and reported behavior among students from health sciences in one region of Spain. J. Food Prot. 2005, 68, 2631–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Vitória, A.G.; de Souza Couto Oliveira, J.; de Almeida Pereira, L.C.; de Faria, C.P.; de São José, J.F.B. Food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices of food handlers: A cross-sectional study in school kitchens in Espírito Santo, Brazil. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Wehedy, A.; Faisal, S.; Omar, N.; Elsherbeny, E. Knowledge, attitude and practice of food handlers towards food safety. Egypt. J. Occup. Med. 2021, 45, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, M.; Alam, M.J.; Parikh, P.; De Steur, H. Understanding food safety knowledge, attitude, and practices of consumers and vendors: An umbrella review. Food Control 2025, 171, 111094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim-Lim, S.A.; Mohamed, K.; Sukki, F.M.; David, W.; Ungku Zainal Abidin, U.F.; Jamaludin, A.A. Food Safety Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices of Food Handlers in Restaurants in Malé, Maldives. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanin, L.M.; da Cunha, D.T.; de Rosso, V.V.; Capriles, V.D.; Stedefeldt, E. Knowledge, attitudes and practices of food handlers in food safety: An integrative review. Food Res. Int. 2017, 100, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzhrani, W.F.; Shatwan, I.M. Food Safety Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices of Restaurant Food Handlers in Jeddah City, Saudi Arabia. Foods 2024, 13, 2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunadu, A.P.; Ofosu, D.B.; Aboagye, E.; Tano-Debrah, K. Food safety knowledge, attitudes and self-reported practices of food handlers in institutional foodservice in Accra, Ghana. Food Control 2016, 69, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, L.C.; Hillers, V.N.; Chen, G.; Bergmann, V.; Kendall, P.; Schroeder, M. Design and development of food safety knowledge and attitude scales for consumer food safety education. J. Am. Diet Assoc. 2004, 104, 1671–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juarez-Medel, C.A.; Toledo-Ortiz, R.; Gonzalez-Rojas, J.M.; Reyna-Alvarez, M.A.; Olivares-Trejo, M.P.; Arriaga-Rodriguez, S.; Alvarado-Castro, V.M.; Esteves-Garcia, F.; Davalos-Martinez, A.; Diego-Galeana, A.J.I.; et al. Primary healthcare knowledge, attitudes, and practices among the personnel of a secondary hospital in Acapulco, Mexico. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2024, 28, 101659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shacho, E.; Ambelu, A.; Yilma, D. Knowledge, attitude, and practice of healthcare workers towards healthcare- associated infections in Jimma University Medical Center, southwestern Ethiopia: Using structural equation model. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2024, 24, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, L.; Shi, Y.; Li, S.; Jiang, K.; Zhang, L.; Wen, Y.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, Y. Healthy Diet-Related Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice (KAP) and Related Socio-Demographic Characteristics among Middle-Aged and Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Survey in Southwest China. Nutrients 2024, 16, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammouh, F.; Abdullah, M.; Al-Bakheit, A.; Al-Awwad, N.J.; Dabbour, I.; Al-Jawaldeh, A. Nutrition Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices (KAPs) among Jordanian Elderly-A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angarita-Díaz, M.D.P.; Colmenares-Pedraza, J.A.; Agudelo-Sanchez, V.; Mora-Quila, J.A.; Rincón-Mejia, L.S. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Associated with the Selection of Sweetened Ultra-Processed Foods and Their Importance in Oral Health. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, D.G.; Woldesenbet, T.T.; Molla, W.; Zeleke, E.D.; Simie, T.G. Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice of mothers/caregivers on infant and young child feeding in Assosa Woreda, Assosa Zone, Benshangul Gumuz Region, Western Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Arch. Public Health 2021, 79, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante, D.O.; Dai, A.; Walker, A.N.; Zhou, Z.; Kpogo, S.A.; Lu, R.; Huang, K.; Zou, J. Assessing hypertension and diabetes knowledge, attitudes and practices among residents in Akatsi South District, Ghana using the KAP questionnaire. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1056999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincă, F.I.; Dimitriu, B.A.; Săndulescu, O.; Sîrbu, V.D.; Săndulescu, M. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Dental Students from Romania Regarding Self-Perceived Risk and Prevention of Infectious Diseases. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turki, Y.; Saleh, S.; Albaik, S.; Barham, Y.; van de Vrie, D.; Shahin, Y.; Hababeh, M.; Armagan, M.; Seita, A. Assessment of the knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) among UNRWA* health staff in Jordan concerning mental health programme pre-implementation: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Ment. Health Syst. 2020, 14, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.H.; Ying, L.H.; Boon Hong, M.L.; Sze Nee, A.W.; Ying, L.S.; Ramachandram, D.S.; Hassan, B.A. Development and validation of a knowledge, attitude, and practice (KAP) questionnaire for skin cancer in the general public: KAP-SC-Q. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2024, 20, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. Knowledge, Attitudes and Perceptions (KAP) Community Survey Towards Women’s Participation in Public Life. 2021. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/jo/00f12b99193a7fe42e9e128a2b06985c527c3c0043f76952c9f763da0159d3eb.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Majowicz, S.E.; Hammond, D.; Dubin, J.A.; Diplock, K.J.; Jones-Bitton, A.; Steven Rebellato, S.; Leatherdale, S.T. A longitudinal evaluation of food safety knowledge and attitudes among Ontario high school students following a food handler training program. Food Control 2017, 76, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Bo, L.; Zhou, X. Knowledge, attitude, and practice toward foodborne disease among Chinese college students: A cross-sectional survey. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1435486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, S.J. Foodborne Diseases: Prevalence of Foodborne Diseases in Europe. Encycl. Food Saf. 2014, 302–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) | European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). The European Union One Health 2023 Zoonoses report. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e9106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirado, C.; Schmidt, K. WHO surveillance programme for control of foodborne infections and intoxications: Preliminary results and trends across greater Europe. World Health Organization. J. Infect. 2001, 43, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deac, L.M. Review on Epidemiological Survey on Foodborne Infection in Romania. J. Bacteriol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 4, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Food Code. 2017. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/resources-you-food/hfp-education-resource-library (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- Amodio, E.; Calamusa, G.; Tiralongo, S.; Lombardo, F.; Genovese, D. A survey to evaluate knowledge, attitudes, and practices associated with the risk of foodborne infection in a sample of Sicilian general population. AIMS Public Health 2022, 9, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, Y.; Waddell, L.; Harding, S.; Greig, J.; Mascarenhas, M.; Sivaramalingam, B.; Pham, M.T.; Papadopoulos, A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of food safety education interventions for consumers in developed countries. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insfran-Rivarola, A.; Tlapa, D.; Limon-Romero, J.; Baez-Lopez, Y.; Miranda-Ackerman, M.; Arredondo-Soto, K.; Ontiveros, S. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Food Safety and Hygiene Training on Food Handlers. Foods 2020, 9, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EC) No. 2073/2005 of 15 November 2005 on microbiological criteria for foodstuffs. Off. J. Eur. Union 2005, 338, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sakkaf, A. Domestic food preparation practices: A review of the reasons for poor home hygiene practices. Health Promot. Int. 2015, 30, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, C.J.; Powell, D.A. Where does foodborne illness happen-in the home, at foodservice, or elsewhere-and does it matter? Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2009, 6, 1121–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holst, M.M.; Wittry, B.C.; Crisp, C.; Torres, J.; Irving, D.; Nicholas, D. Contributing Factors of Foodborne Illness Outbreaks—National Outbreak Reporting System, United States, 2014–2022. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 2025, 74, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallo, M.; Ferrara, L.; Calogero, A.; Montesano, D.; Naviglio, D. Relationships between food and diseases: What to know to ensure food safety. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics of Respondents | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Women | 979 (76.7%) |

| Men | 293 (22.9%) |

| Other gender | 5 (0.4%) |

| Age | |

| Age < 21 years | 658 (51.5%) |

| Age 21–23 years | 380 (29.8%) |

| Age 24–26 | 224 (17.5%) |

| Age ˃ 26 years | 15 (1.2%) |

| Living space | |

| Permanent residence | 497 (38.9%) |

| Property rented during university studies | 472 (37%) |

| Room at the student dormitory of the University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Carol Davila” Bucharest | 253 (19.8%) |

| Private dormitory | 55 (4.3%) |

| Year of study | |

| Preclinical university studies: | 626 (49%) |

| Year I | 89 (7%) |

| Year II | 294 (23%) |

| Year III | 243 (19%) |

| Clinical university studies: | 651 (51%) |

| Year IV | 178 (14%) |

| Year V | 243 (19%) |

| Year VI | 230 (18%) |

| Question | Frequency of Correct Answers (No.) |

|---|---|

| Q1. Which of the following pathogens can be transmitted through food? | 154 |

| Q7. How can you tell if your food is contaminated with bacterial toxins? | 473 |

| Q8. What makes bacteria multiply? | 511 |

| Q5. How do you defrost a food product correctly? | 556 |

| Q4. How long should we keep food outside the refrigerator after it has been thermally processed? | 577 |

| Q3. What is the optimal storage interval for perishable foods in the refrigerator? | 691 |

| Q10. What methods should be used to avoid food contamination? | 709 |

| Q9. What are the most common symptoms of food poisoning? | 711 |

| Q2. Cross-contamination refers to the process of transfer pathogen agents from other sources in food? | 835 |

| Q6. Does refrigeration eliminate all pathogens that may be present in food? | 862 |

| Frequency (no.) | Average Score | SD | Minimum Score | Maximum Score | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||

| Women | 979 | 59.3 | 15.0 | 11 | 100 | |

| Male | 293 | 58.4 | 14.9 | 11 | 100 | 0.704 |

| Other | 5 | 58.4 | 23.2 | 17 | 72 | |

| Year of study | ||||||

| Preclinical 1 | 626 | 57.9 | 15.0 | 11 | 100 | 0.005 * |

| Clinic 2 | 651 | 60.2 | 15.0 | 14 | 100 |

| Question | Preclinical Years | Clinical Years | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (N = 626) | Percentage (%) | Frequency (N = 651) | Percentage (%) | p-Value | |

| Q1.Which of the following pathogen agents can be transmitted through food? | 64 | 10.2% | 90 | 13.8% | 0.048 * |

| Q2. Cross-contamination refers to the process of transfer of pathogens from other food sources? | 408 | 65.2% | 427 | 65.6% | 0.876 |

| Q3. What is the optimal storage interval for perishable foods in the fridge? | 344 | 55% | 347 | 53.3% | 0.554 |

| Q4. How long should we keep food outside the refrigerator after it has been thermally processed? | 285 | 45.5% | 292 | 44.9% | 0.809 |

| Q5. How do you defrost a food product correctly? | 247 | 39.5% | 309 | 47.5% | 0.004 * |

| Q6. Does refrigeration eliminate all pathogens that may be present in food? | 421 | 67.3% | 441 | 67.7% | 0.852 |

| Q7. How can you tell if your food is contaminated with bacterial toxins? | 237 | 37.9% | 236 | 36.3% | 0.552 |

| Q8. What promotes breeding bacteria? | 270 | 43.1% | 241 | 37% | 0.026 * |

| Q9. What are the most common symptoms of food poisoning? | 288 | 46% | 423 | 65% | <0.0001 * |

| Question | Every Time | Sometimes | No | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (No.) | Percentage (%) | Frequency (No.) | Percentage (%) | Frequency (No.) | Percentage (%) | |

| Q1. Do you wash your hands with soap and water before preparing food? | 1210 | 94.8% | 66 | 5.2% | 1 | 0.05% |

| Q2. Do you wash your hands with soap and water after handling raw meat (pork, chicken, seafood)? | 1143 | 89.5% | 119 | 9.3% | 15 | 1.2% |

| Q3. Do you wash your hands with soap and water after food preparation? | 1047 | 82% | 206 | 16.1% | 24 | 1.9% |

| Q4. Do you eat food that has been left at room temperature for more than 2 h? | 420 | 32.9% | 666 | 52.1% | 191 | 15% |

| Q5. Do you wash fruits and vegetables before eating them? | 1230 | 96.3% | 45 | 3.5% | 2 | 0.12% |

| Q6. Do you wear accessories such as rings or bracelets while cooking? | 134 | 10.5% | 345 | 27% | 798 | 62.5% |

| Q7. Do you wash the knife and cutting board after each use, especially after cutting meat? | 865 | 67.7% | 328 | 25.7% | 84 | 6.6% |

| Q8. Do you wash eggs before using them for meal preparation? | 383 | 30% | 362 | 29% | 532 | 41% |

| Q9. Do you read and observe the storage conditions on food product packaging? | 686 | 53.8% | 563 | 44.1% | 28 | 2.2% |

| Q10. Do you read and respect the expiration date on food product labels? | 1145 | 89.7% | 125 | 9.8% | 7 | 0.6% |

| Question | Women | Male | Other | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (No. = 979) | Percentage (%) | Frequency No. = 293) | Percentage (%) | Frequency (No. = 5) | Percentage (%) | p-Value | |

| Q1. Do you wash your hands with soap and water before preparing food? | 941 | 96.1% | 265 | 90.4% | 4 | 80% | 0.0008 * |

| Q2. Do you wash your hands with soap and water after handling raw meat (pork, chicken, seafood) | 880 | 89.9% | 259 | 88.4% | 4 | 80% | 0.6318 |

| Q3. Do you wash your hands with soap and water after preparing food? | 815 | 83.6% | 226 | 77.1% | 3 | 60% | 0.025 * |

| Q4. Do you eat food that has been left at room temperature for more than 2 h? | 154 | 15.7% | 36 | 12.3% | 0 | 0% | 0.1843 |

| Q5. Do you wash fruits and vegetables before eating them? | 955 | 97.5% | 271 | 92.5% | 5 | 100% | 0.0003 * |

| Q6. Do you wear accessories such as rings or bracelets while cooking? | 555 | 56.7% | 241 | 82.3% | 2 | 40% | <0.0001 * |

| Q7. Do you wash the knife and cutting board after each use, especially after cutting meat? | 684 | 69.9% | 179 | 61.1% | 2 | 40% | 0.009 * |

| Q8. Do you wash eggs before using them for meal preparation? | 296 | 30.2% | 86 | 29.4% | 1 | 20% | 0.8428 |

| Q9. Do you read and observe the storage conditions on food product packaging? | 512 | 52.3% | 171 | 58.4% | 3 | 60% | 0.1693 |

| Q10. Do you read and respect the expiration date on food product labels? | 881 | 90% | 260 | 88.7% | 4 | 80% | 0.6751 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nițescu, M.; Nedelescu, M.M.; Moroşan, E.; Simionescu, A.A.; Furtunescu, F.L.; Ştefănescu, B.E.; Tusaliu, M.; Panaitescu, E.; Stanciu, A.-M.; Stoian, I.M. Assessment of Food Safety Knowledge and Practices Among Medical Students. Foods 2025, 14, 1636. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14091636

Nițescu M, Nedelescu MM, Moroşan E, Simionescu AA, Furtunescu FL, Ştefănescu BE, Tusaliu M, Panaitescu E, Stanciu A-M, Stoian IM. Assessment of Food Safety Knowledge and Practices Among Medical Students. Foods. 2025; 14(9):1636. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14091636

Chicago/Turabian StyleNițescu, Maria, Mirela Maria Nedelescu, Elena Moroşan, Anca Angela Simionescu, Florentina Ligia Furtunescu, Bianca Eugenia Ştefănescu, Mihail Tusaliu, Eugenia Panaitescu, Alin-Marian Stanciu, and Irina Mihaela Stoian. 2025. "Assessment of Food Safety Knowledge and Practices Among Medical Students" Foods 14, no. 9: 1636. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14091636

APA StyleNițescu, M., Nedelescu, M. M., Moroşan, E., Simionescu, A. A., Furtunescu, F. L., Ştefănescu, B. E., Tusaliu, M., Panaitescu, E., Stanciu, A.-M., & Stoian, I. M. (2025). Assessment of Food Safety Knowledge and Practices Among Medical Students. Foods, 14(9), 1636. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14091636