The Theory and Practice of Sensory Evaluation of Vinegar: A Case of Italian Traditional Balsamic Vinegar

Abstract

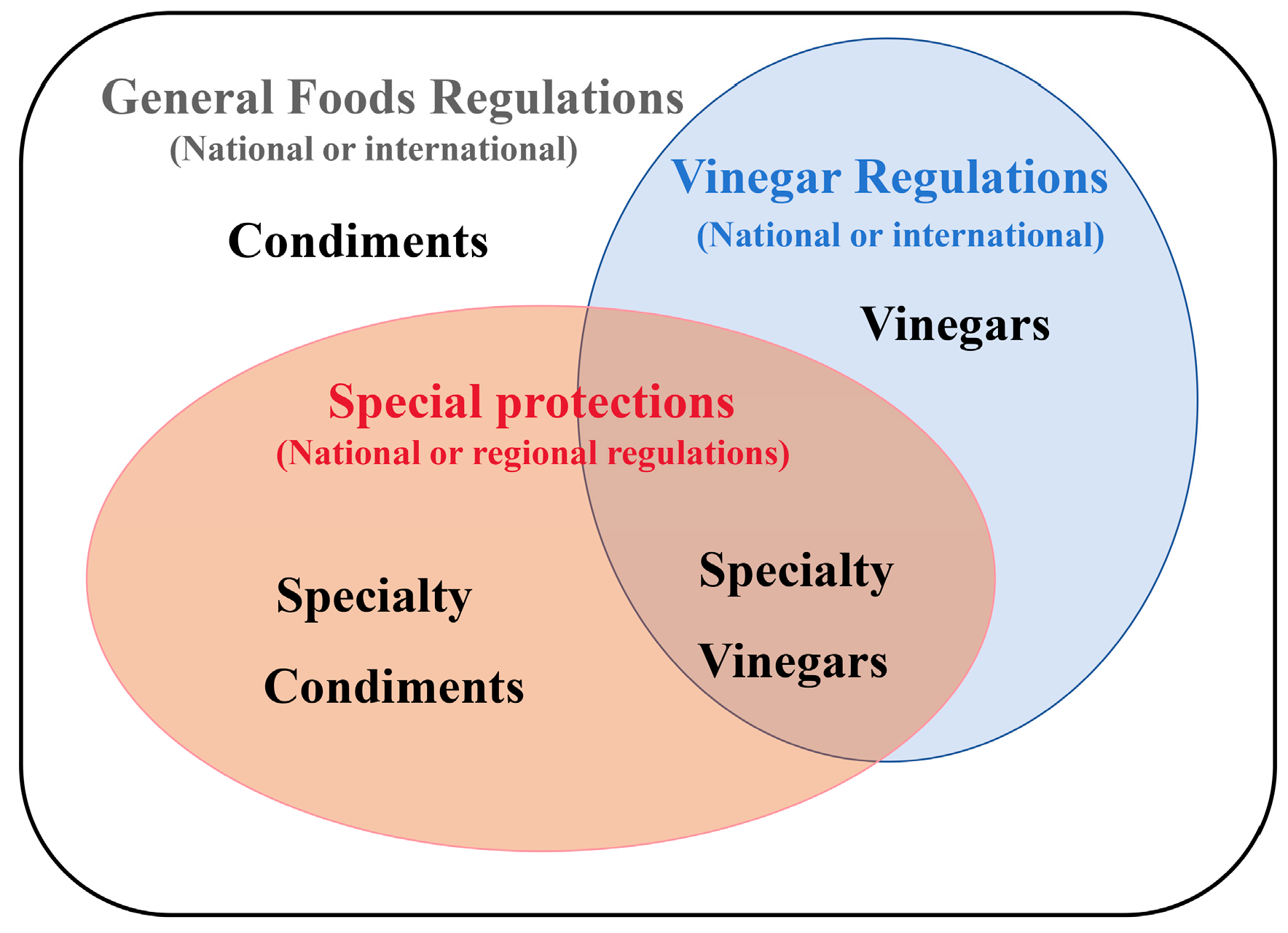

1. Introduction

2. Importance of Vinegar Sensory Analysis to Find Potential Consumers

3. The Shortcomings of the Existing Vinegar Sensory Analysis

3.1. The Shortcomings of the Tasting Procedure for Vinegar

3.2. The Shortcomings of Descriptors in Vinegar Sensory Analysis

4. Structuring a Vinegar Sensory Evaluation System: Key Descriptors, Recording Methods and Temporal Sequences

4.1. Important and/or Necessary Descriptors for Vinegar Evaluation

4.2. The Recording Board for Vinegar Sensory Perception

4.3. Temporal Sequence of Vinegar Sensory Perceptions

5. The Practice of the Sensory Evaluation of Vinegar: Taking the Italian Traditional Balsamic Vinegar as an Example

5.1. The Factors Affecting Vinegar Sensory Evaluation

5.2. Taster Training

5.3. Information on Vinegar Samples

5.4. Other Information of Vinegar Samples

5.5. The Practice of the Sensory Evaluation of the Italian Traditional Balsamic Vinegar

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABT | Italian Traditional Balsamic Vinegar |

| PDO | Protected designation of origin |

| PGI | Protected geographical indication |

References

- Cayot, N. Sensory quality of traditional foods. Food Chem. 2007, 101, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihafu, F.D.; Issa, J.Y.; Kamiyango, M.W. Implication of sensory evaluation and quality assessment in food product development: A review. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. 2020, 8, 690–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.S.Q.; Dias, L.G.; Teixeira, A. Emerging methods for the evaluation of sensory quality of food: Technology at service. Curr. Food Sci. Technol. Rep. 2024, 2, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, H.; Bleibaum, R.N.; Thomas, H.A. Sensory Evaluation Practices, 5th ed.; Academic Press: Kolkata, India, 2020; pp. 1–414. [Google Scholar]

- Talavera-Bianchi, M.; Chambers, D.H. Simplified lexicon to describe flavor characteristics of western European cheeses. J. Sens. Stud. 2008, 23, 468–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardello, A.V.; Llobell, F.; Jin, D.; Ryan, G.S.; Jaeger, S.R. Sensory drivers of liking, emotions, conceptual and sustainability concepts in plant-based and dairy yoghurts. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 113, 105077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza Gonzaga, L.; Capone, D.L.; Bastian, S.E.P.; Jeffery, D.W. Defining wine typicity: Sensory characterisation and consumer perspectives. Aust. J. Grape Wine R. 2021, 27, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.U.; Kim, T.W.; Lee, S.J. Characterization of Korean distilled liquor, soju, using chemical, HS-SPME-GC-MS, and sensory descriptive analysis. Molecules 2022, 27, 2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomis-Bellmunt, A.; Claret, A.; Guerrero, L.; Pérez-Elortondo, F.J. Sensory evaluation of protected designation of origin wines: Development of olfactive descriptive profile and references. Food Res. Int. 2024, 176, 113828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmer, A.; Kleypas, J.; Orlowski, M. Wine sensory experience in hospitality education: A systematic review. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 1365–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paissoni, M.A.; Motta, G.; Giacosa, S.; Rolle, L.; Gerbi, V.; Río Segade, S. Mouthfeel subqualities in wines: A current insight on sensory descriptors and physical–chemical markers. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 3328–3365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittari, E.; Moio, L.; Piombino, P. Interactions between polyphenols and volatile compounds in wine: A literature review on physicochemical and sensory insights. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ker, J.K.; Lee, C.S.; Chen, Y.C.; Chiang, M.C. Exploring Taiwanese consumer dietary preferences for various vinegar condiments: Novel dietary patterns across diverse cultural contexts. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jürkenbeck, K.; Spiller, A. Importance of sensory quality signals in consumers’ food choice. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 90, 104155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesfaye, W.; Morales, M.L.; Garcia-Parrilla, M.C.; Troncoso, A.M. Improvement of wine vinegar elaboration and quality analysis: Instrumental and human sensory evaluation. Food Rev. Int. 2009, 25, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ríos-Reina, R.; del Pilar Segura-Borrego, M.; Úbeda, C.; Morales, M.L.; Callejón, R.M. Fraud, Quality, and methods for characterization and authentication of vinegars. In Advances in Vinegar Production; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; pp. 441–467. [Google Scholar]

- Góamez, M.L.M.; Bellido, B.B.; Tesfaye, W.; Fernandez, R.M.C.; Valencia, D.; Fernandez-Pachón, M.S.; García-Parrilla, M.C.; González, A.M.T. Sensory evaluation of sherry vinegar: Traditional compared to accelerated aging with oak chips. J. Food Sci. 2006, 71, S238–S242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segura-Borrego, M.d.P.; Ramírez, P.; Ríos-Reina, R.; Morales, M.L.; Callejón, R.M.; León Gutiérrez, J.M. Impact of fig maceration under various conditions on physicochemical and sensory attributes of wine vinegar: A comprehensive characterization study. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 8945–8968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrico, D.D.; Fuentes, S.; Viejo, C.G.; Ashman, H.; Dunshea, F.R. Cross-cultural effects of food product familiarity on sensory acceptability and non-invasive physiological responses of consumers. Food Res. Int. 2019, 115, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrico, D.D.; Mehta, A.; Borssato, A.B. New methods to assess sensory responses: A brief review of innovative techniques in sensory evaluation. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2023, 49, 100978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeppa, G.; Gambigliani Zoccoli, M.; Nasi, E.; Masini, G.; Meglioli, G.; Zappino, M. Descriptive sensory analysis of Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena DOP and Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Reggio Emilia DOP. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 3737–3742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sipos, L.; Nyitrai, Á.; Hitka, G.; Friedrich, L.F.; Kókai, Z. Sensory panel performance evaluation—Comprehensive review of practical approaches. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmetti, F.; Solieri, L.; Bonciani, T.; Zanichelli, G.; Giudici, P. Sensory analysis of traditional balsamic vinegars: Current state and future perspectives. Acetic Acid Bact. 2014, 3, 4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletto, L.; Rossetto, L. A hedonic analysis of retail Italian vinegars. Wine Econ. Policy 2015, 4, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattia, G. Balsamic vinegar of Modena: From product to market value: Competitive strategy of a typical Italian product. Br. Food J. 2004, 106, 722–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradini, G. The Flavor of Vinegars; Università degli studi di Modena e Reggio Emilia: Modena, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Perini, M.; Pianezze, S.; Paolini, M.; Larcher, R. High-density balsamic vinegar: Application of stable isotope ratio analysis to determine watering down. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 72, 1845–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpou, A.; Mantzourani, I.; Bekatorou, A.; Alexopoulos, A.; Plessas, S. Current trends in balsamic/aged vinegar production and research. In Advances in Vinegar Production; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; pp. 155–170. [Google Scholar]

- Giudici, P. Cognitive bias of sensory analysis: The case of Traditional Balsamic Vinegar. In Quaderni di Agricoltura; Recos: Reggio Emilia, Italy, 2023; Volume 2, p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Lemmetti, F.; Giudici, P. Mass balance and age of Traditional Balsamic vinegar. Agric. Food Sci. Environ. Sci. 2010, 230, 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Luzón-Quintana, L.M.; Castro, R.; Durán-Guerrero, E. Biotechnological processes in fruit vinegar production. Foods 2021, 10, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo, C.; Vegas, C.; Mateo, E.; Tesfaye, W.; Cerezo, A.B.; Callejón, R.M.; Poblet, M.; Guillamón, J.M.; Mas, A.; Torija, M.J. Effect of barrel design and the inoculation of Acetobacter pasteurianus in wine vinegar production. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 141, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamini, R.; Panighel, A.; De Marchi, F. Mass spectrometry in the study of wood compounds released in the barrel-aged wine and spirits. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2023, 42, 1174–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmi, C. Relationship between sugar content, total acidity, and crystal by-products in the making of Traditional Balsamic Vinegar of Modena. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2015, 241, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, V.K.; Sharma, S.; Thakur, A.D. Wines: White, red, sparkling, fortified, and cider. In Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 353–406. [Google Scholar]

- Gullo, M.; Verzelloni, E.; Canonico, M. Aerobic submerged fermentation by acetic acid bacteria for vinegar production: Process and biotechnological aspects. Process Biochem. 2014, 49, 1571–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, P.M.; Boselli, E.; Frega, N.G. Structure-composition relationships of the Traditional Balsamic Vinegar close to jamming transition. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 1613–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanarico, D.; Motta, S.; Bertolini, L.; Antonelli, A. HPLC determination of organic acids in traditional balsamic vinegar of Reggio Emilia. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Rel. Technol. 2003, 26, 2177–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocchi, M.; Lambertini, P.; Manzini, D.; Marchetti, A.; Ulrici, A. Determination of carboxylic acids in vinegars and in Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena by HPLC and GC methods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 5255–5261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzidimitriou, E.; Papadopoulou, M.; Lalou, S.; Tsimidou, M.Z. Contribution to the discussion of current state and future perspectives of sensory analysis of balsamic vinegars. Acetic Acid Bact. 2015, 4, 5070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giudici, P.; Gullo, M.; Solieri, L.; Falcone, P.M. Technological and microbiological aspects of traditional balsamic vinegar and their influence on quality and sensorial properties. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2009, 58, 137–182. [Google Scholar]

- Velasco, C.; Jones, R.; King, S.; Spence, C. Assessing the influence of the multisensory environment on the whisky drinking experience. Flavour 2013, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, P.M.; Verzelloni, E.; Tagliazucchi, D.; Giudici, P. A rheological approach to the quantitative assessment of traditional balsamic vinegar quality. J. Food Eng. 2008, 86, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solieri, L.; Giudici, P. Vinegars of the World. In Vinegars of the World; Lisa, S., Paolo, G., Eds.; Springer: Milano, Italy, 2009; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bérodier, F.; Lavanchy, P.; Zannoni, M.; Casals, J.; Herrero, L.; Adamo, C. Guide d’évaluation olfacto-gustative des fromages à pâte dure et semi-dure. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 1997, 30, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavanchy, P.; Bérodier, F.; Zannoni, M.; Noël, Y.; Adamo, C.; Squella, J.; Herrero, L. L’evaluation sensorielle de la texture des fromages à pâte dure ou semi-dure. Etude interlaboratoires. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 1993, 26, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, A.C.; Arnold, R.A.; Buechsenstein, J.; Leach, E.J.; Schmidt, J.O.; Stern, P.M. Modification of a standardized system of wine aroma terminology. Am. J. Enol. Viticult. 1987, 38, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, P.M.; Chillo, S.; Giudici, P.; Del Nobile, M.A. Measuring rheological properties for applications in quality assessment of traditional balsamic vinegar: Description and preliminary evaluation of a model. J. Food Eng. 2007, 80, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellinek, G. Sensory Evaluation of Food. Theory and Practice; Vch Pub, Ellis Horwood Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 1985; pp. 575–656. [Google Scholar]

- Prescott, J.; Stevenson, R.J. Pungency in food perception and preference. Food Rev. Int. 1995, 11, 665–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, G.; Varela, P. Trained vs. consumer panels for analytical testing: Fueling a long lasting debate in the field. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 61, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versari, A.; Parpinello, G.P.; Chinnici, F.; Meglioli, G. Prediction of sensory score of Italian traditional balsamic vinegars of Reggio-Emilia by mid-infrared spectroscopy. Food Chem. 2011, 125, 1345–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio-Ruiz, R.; Barbieri, S.; Gallina Toschi, T.; García-González, D.L. Formulations of rancid and winey-vinegary artificial olfactory reference materials (AORMs) for virgin olive oil sensory evaluation. Foods 2020, 9, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesfaye, W.; Morales, M.L.; Callejón, R.M.; Cerezo, A.B.; Gonzalez, A.G.; Garcia-Parrilla, M.C.; Troncoso, A.M. Descriptive sensory analysis of wine vinegar: Tasting procedure and reliability of new attributes. J. Sens. Stud. 2010, 25, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torri, L.; Jeon, S.-Y.; Piochi, M.; Morini, G.; Kim, K.-O. Consumer perception of balsamic vinegar: A cross-cultural study between Korea and Italy. Food Res. Int. 2017, 91, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Product Categories | Main Ingredients | Permitted Additives | Ageing Time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dyes | Aromas | Thickeners | Emulsifiers | Preservatives | |||

| Traditional Balsamic Vinegar PDO ** | Cooked must | No | No | No | No | No | At least 12 years |

| Balsamic Vinegar of Modena PGI | Wine vinegar, concentrated and/or cooked must | Caramel | Caramel | No | No | Sulphites *** | At least 60 days |

| Glazes, Sauces and Balsamic Condiments | Wine vinegar, sugars | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Aspect | Aroma | Taste | Texture | Trigeminal Sensation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colour | Caramel | Acid | Viscosity | Astringent |

| Wine/Cooked must | Sweet | Pungent | ||

| Wood | Amaro | Spicy | ||

| Fruit | Salty | |||

| Plum/prune | ||||

| Acetic acid | ||||

| Honey | ||||

| Apple | ||||

| Liquorice | ||||

| Mustard | ||||

| Vanilla | ||||

| Carob | ||||

| Spices | ||||

| Coffee | ||||

| Chocolate |

| Attributes | Descriptions | Standards | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caramel | Aroma and flavour associated with caramel syrup | Ildia-type caramel syrup | |

| Wine/ cooked must | |||

| Wood | |||

| Fruit | Aroma associated with different fruits | ||

| Prune | Mixture of 1–2 mL plum juice and 25 mL red wine | Noble et al., 1987 [47] | |

| Acetic acid | Mixture of 2 drops of glacial acetic acid and 50 mL red wine | ||

| Honey | Mixture of 5–8 mL honey in white wine | ||

| Apple | Fresh apple slices in 5 mL apple juice and 25 mL white wine | ||

| Liquorice | Mixture of 1 drop of aniseed extract and 50 mL red wine | ||

| Mostarda | |||

| Vanilla | Aroma associated with vanilla extract | Mixture of 1–2 drops of vanilla extract in 25 mL red wine | |

| Carob | |||

| Spices | 2–3 ground white pepper granules in 25 mL red wine | ||

| Coffee | Aroma associated with coffee beans | 2–4 ground coffee granules | |

| Chocolate | Aroma associated with chocolate | 2–5 mL chocolate flavouring or ½ teaspoon cocoa powder in 25 mL red wine | |

| Acid | Sensation produced by aqueous citric acid solution | Aqueous solution of citric acid (0.43 g/L) | Giudici et al., 2009 [41] |

| Sweet | Sensation produced by aqueous sucrose solution | Aqueous sucrose solution (5.76 g/L) | |

| Bitter | Sensation produced by aqueous solution of various compounds including caffeine | Aqueous caffeine solution (0.195 g/L) | |

| Salty | Sensation produced by aqueous solution of sodium chloride | Sodium chloride aqueous solution (1.19 g/L) | |

| Viscosity | Instrumental measurement of slip resistance in rotary motion at controlled speed | Calculated as stress/speed ratio under Newtonian conditions | Falcone et al., 2007 [48] |

| Astringent | Attribute associated with the sensation of astringency produced by pure substance or specific mixtures | Aqueous solution of potassium aluminium sulphate hydrate (0.05% aluminium by weight) | Jellinek [49] |

| Pungent | Irritating sensation perceived inside the mouth | 1.5 mL of 0.5% by weight aqueous solution of Cayenne after 5 min boiling and subsequent filtration with 10 g of quark | Prescott and Stevenson [50] |

| Spicy | Sensation of heat produced inside the oral cavity (e.g., by peppers) | Olive oil | Jellinek [49] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, F.; Ma, Y.; Corradini, G.; Giudici, P. The Theory and Practice of Sensory Evaluation of Vinegar: A Case of Italian Traditional Balsamic Vinegar. Foods 2025, 14, 893. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14050893

Chen F, Ma Y, Corradini G, Giudici P. The Theory and Practice of Sensory Evaluation of Vinegar: A Case of Italian Traditional Balsamic Vinegar. Foods. 2025; 14(5):893. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14050893

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Fusheng, Yanqin Ma, Giuseppe Corradini, and Paolo Giudici. 2025. "The Theory and Practice of Sensory Evaluation of Vinegar: A Case of Italian Traditional Balsamic Vinegar" Foods 14, no. 5: 893. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14050893

APA StyleChen, F., Ma, Y., Corradini, G., & Giudici, P. (2025). The Theory and Practice of Sensory Evaluation of Vinegar: A Case of Italian Traditional Balsamic Vinegar. Foods, 14(5), 893. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14050893