Comparative Analysis of Dried Water Bamboo Shoots Using Different Drying Methods: Physicochemical Properties and Flavor

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Determination of Moisture Content

2.3. Color

2.4. Texture

2.5. Rehydration Ratio

2.6. Determination of Vitamin C Content

2.7. Determination of Total Phenol Content

2.8. Microstructure Analysis

2.9. Browning Degree Analysis

2.10. Transverse Magnetic Relaxation Time (T2)

2.11. Volatile Organic Compounds

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Drying Time Analysis

3.2. Effect of Drying Methods on the Texture, Color, and Browning Degree of Dried WBSs

3.3. Effect of Drying Methods on the VC and Total Phenol Content in Dried WBSs

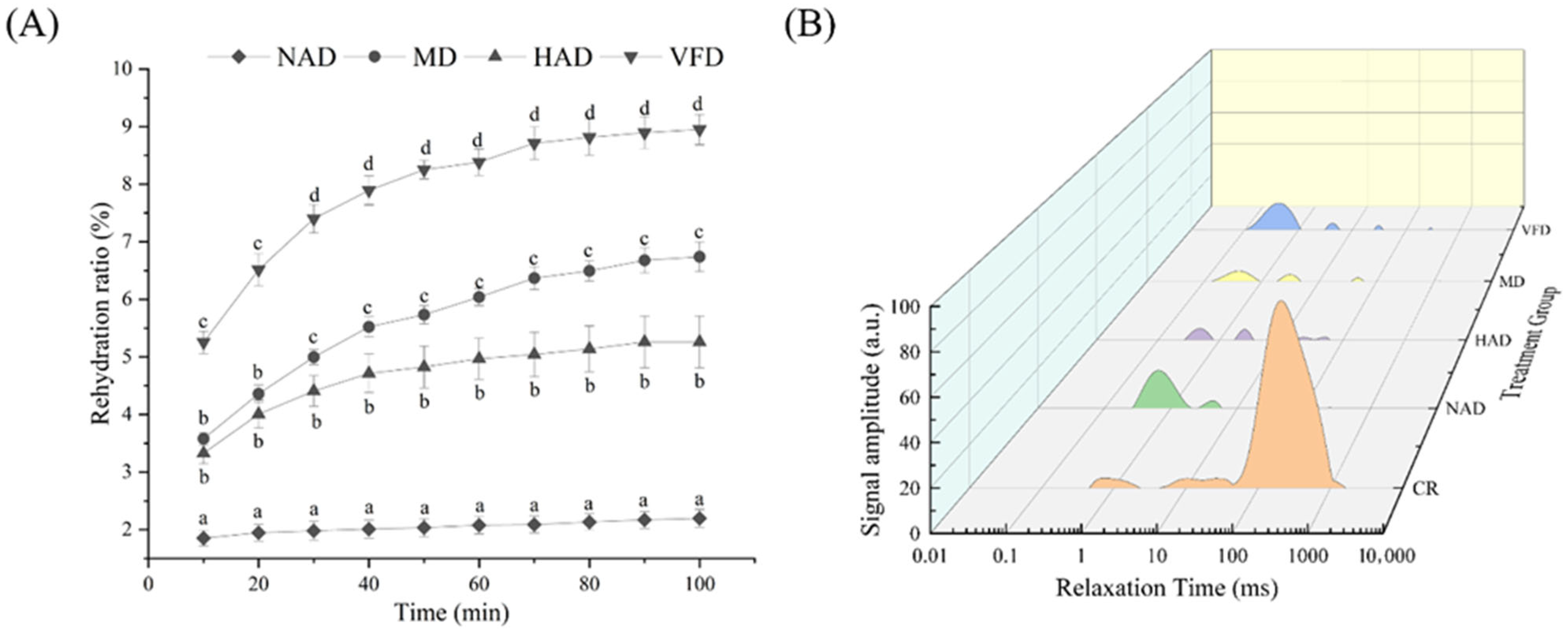

3.4. Effect of Drying Method on Rehydration Ratio, Microstructure, and Water Distribution of Dried WBS

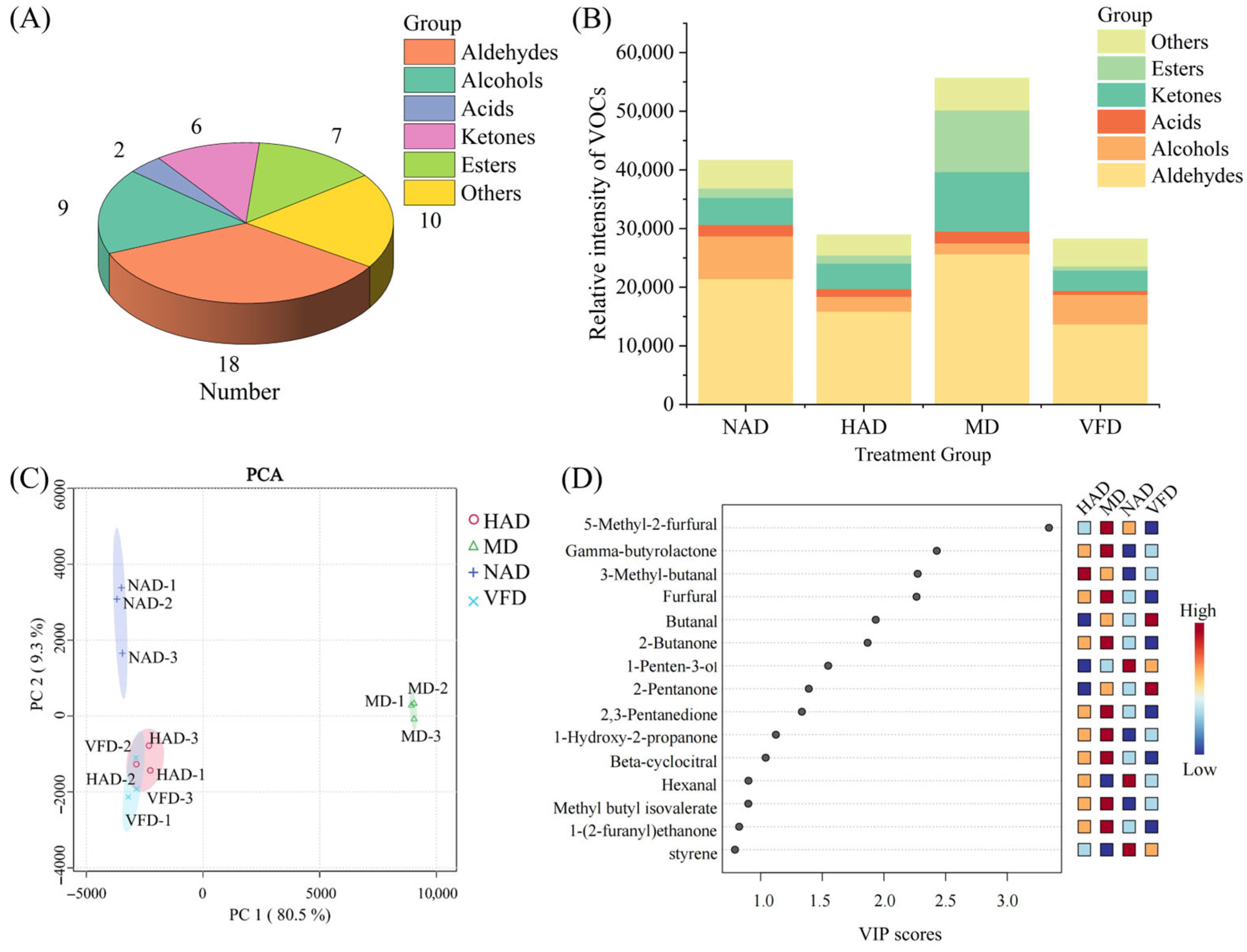

3.5. Impact of Drying Methods on the Volatile Organic Compounds in Dried WBSs

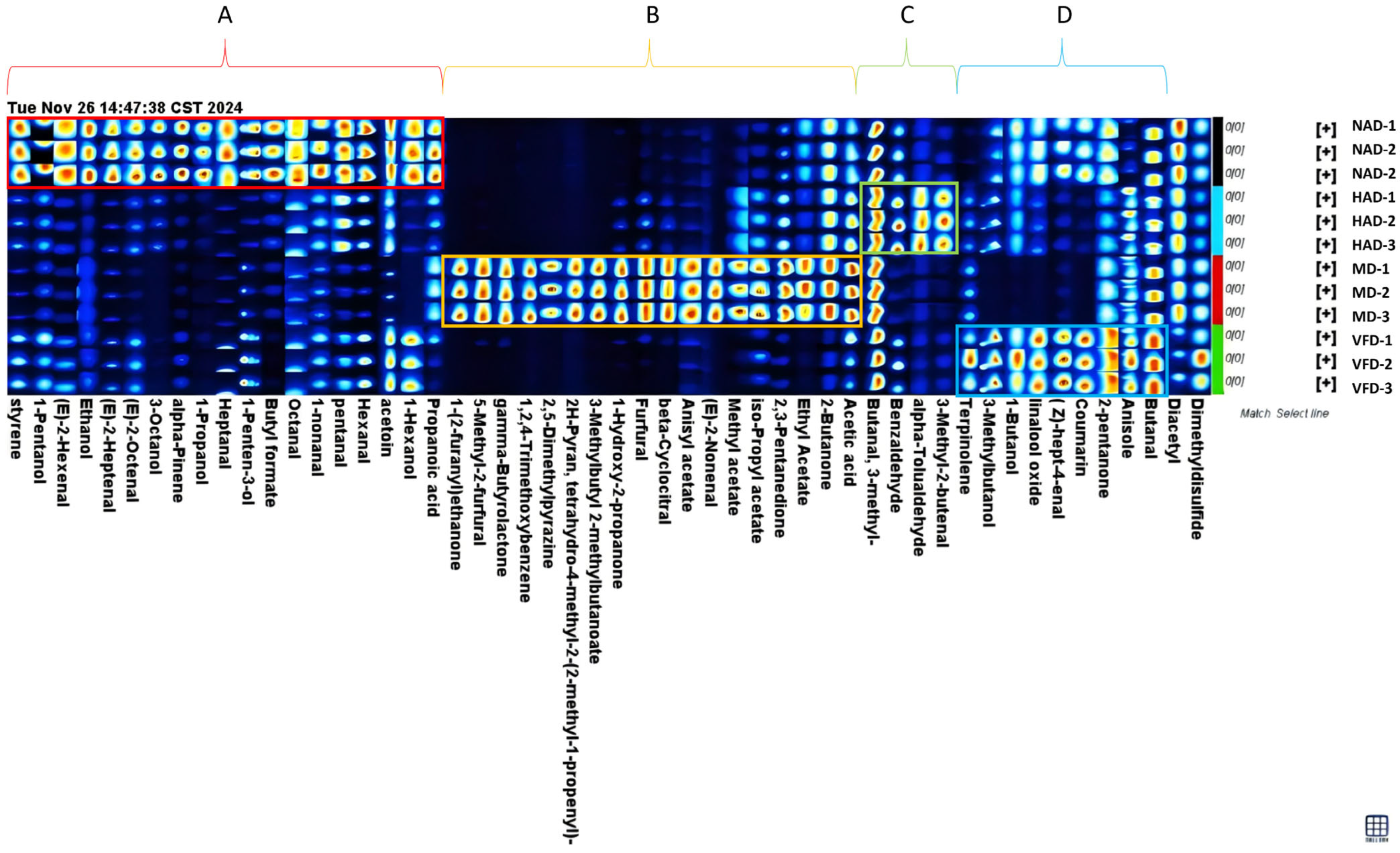

3.6. The Fingerprint Map Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WBS | Water bamboo shoots |

| NAD | Natural air drying |

| HAD | Hot air drying |

| MD | Microwave drying |

| VFD | Vacuum freeze drying |

| VOC | Volatile organic compound |

| GC-IMS | Gas chromatography–ion mobility spectrometry |

References

- Chu, C.; Du, Y.; Yu, X.; Shi, J.; Yuan, X.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, N. Dynamics of antioxidant activities, metabolites, phenolic acids, flavonoids, and phenolic biosynthetic genes in germinating Chinese wild rice (Zizania latifolia). Food Chem. 2020, 318, 126483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Murtaza, A.; Zhu, L.; Iqbal, A.; Ali, S.W.; Xu, X.; Pan, S.; Hu, W. High pressure CO2 treatment alleviates lignification and browning of fresh-cut water-bamboo shoots (Zizania latifolia). Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2021, 182, 111690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, P.; Ding, C.; Lu, J.; Bai, W.; Song, Z.; Che, C.; Chen, H.; Jia, Y. Comparative analysis of electrohydrodynamic, hot air, and natural air drying techniques on quality attributes and umami enhancement in king oyster mushroom (Pleurotus eryngii). LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 225, 117918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, S.; Ramanathan, S.; Basak, T. Microwave food processing—A review. Food Res. Int. 2013, 52, 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yi, J.; He, J.; Dong, J.; Duan, X. Comparative evaluation of quality characteristics of fermented napa cabbage subjected to hot air drying, vacuum freeze drying, and microwave freeze drying. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 192, 115740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, X.; Lyu, Y.; Li, Y.; He, R.; Chen, H. Metabolomics analysis reveals the non-enzymatic browning mechanism of green peppers (Piper nigrum L.) during the hot-air drying process. Food Chem. 2025, 464, 141654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, H.; Li, Z.; Hui, J.; Raghavan, G.S.V. Effect of relative humidity on microwave drying of carrot. J. Food Eng. 2016, 190, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondaruk, J.; Markowski, M.; Błaszczak, W. Effect of drying conditions on the quality of vacuum-microwave dried potato cubes. J. Food Eng. 2007, 81, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luka, B.S.; Mactony, M.J.; Vihikwagh, Q.M.; Oluwasegun, T.H.; Zakka, R.; Joshua, B.; Muhammed, I.B. Microwave-based and convective drying of cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var capitata L.): Computational intelligence modeling, thermophysical properties, quality and mid-infrared spectrometry. Meas. Food 2024, 15, 100187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Li, D.; Lv, H.; Jin, X.; Han, Q.; Su, D.; Wang, Y. Recent development of microwave fluidization technology for drying of fresh fruits and vegetables. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 86, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Gao, Y.; Hu, B.; Wang, J.; Si, X.; Zhu, B.; Fan, J.; Zhang, B. Freeze-thaw pretreatment improves the vacuum freeze-drying efficiency and storage stability of goji berry (Lycium barbarum. L.). LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 189, 115439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Yang, F.; Yan, L.; Wu, J.; Bi, S.; Liu, Y. Characterization of key aroma-active compounds in fresh and vacuum freeze-drying mulberry by molecular sensory science methods. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2024, 133, 106387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Hu, W.; Niaz, N.; Zhu, L.; Xu, X.; Pan, S. Comprehensive widely targeted metabolomics unveils the regulatory mechanisms of high-pressure CO2 in preserving fresh-cut water bamboo shoots (Zizania latifolia) quality. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 227, 113629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Feng, K.; Luan, J.; Cao, Y.; Rahman, K.; Ba, J.; Han, T.; Su, J. Characterization of saffron from different origins by HS-GC-IMS and authenticity identification combined with deep learning. Food Chem. X 2024, 24, 101981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, P.; Hu, H.-W.; Cui, A.-H.; Tang, H.-J.; Liu, Y.-G. HS-GC-IMS with PCA to analyze volatile flavor compounds of honey peach packaged with different preservation methods during storage. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 149, 111963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assad, T.; Jabeen, A.; Roy, S.; Bhat, N.; Maqbool, N.; Yadav, A.; Aijaz, T. Using an image processing technique, correlating the lycopene and moisture content in dried tomatoes. Food Humanit. 2024, 2, 100186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, Q. Prediction of color and moisture content for vegetable soybean during drying using hyperspectral imaging technology. J. Food Eng. 2014, 128, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Jiang, R.; Liu, J.; Pan, Y.; Gao, X. Comparison of various drying methods on color, texture, nutritional components, and antioxidant activity of tumorous stem mustard. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 201, 116241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Geng, J.; Han, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, H.; Li, P. Effect of drying technology on the physical, rehydration, flavor, and allicin content of single-clove garlic. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222, 120020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, D.; Lin, L.; Li, R.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, J.; Jiang, S. Effect of cold plasma and ultrasonic pretreatment on drying characteristics and nutritional quality of vacuum freeze-dried kiwifruit crisps. Ultrason. Sonochem 2025, 112, 107212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niveditha, A.; Chidanand, D.V.; Sunil, C.K. Effect of ultrasound-assisted drying on drying kinetics, color, total phenols content and antioxidant activity of pomegranate peel. Meas. Food 2023, 12, 100114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamkari, A.; Dadashi, S.; Heshmati, M.K.; Dehghannya, J.; Ramezan, Y. The effect of cold plasma pretreatment on drying efficiency of beetroot by intermittent microwave-hot air (IMHA) hybrid dryer method: Assessing drying kinetic, physical properties, and microstructure of the product. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 212, 117010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udomkun, P.; Nagle, M.; Mahayothee, B.; Nohr, D.; Koza, A.; Müller, J. Influence of air drying properties on non-enzymatic browning, major bio-active compounds and antioxidant capacity of osmotically pretreated papaya. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 60, 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Yue, X.; Gu, Y.; Yang, T. Assessment of maize seed vigor under saline-alkali and drought stress based on low field nuclear magnetic resonance. Biosyst. Eng. 2022, 220, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Nie, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zheng, T.; Song, J.; Zhang, C.; Chen, H.; Lin, D.; Cao, S.; Xu, S. Effect of hot-air drying processing on the volatile organic compounds and maillard precursors of Dictyophora Rubrovalvata based on GC-IMS, HPLC and LC-MS. Food Chem. 2025, 463, 141074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Li, R.; Liao, Y.; Dong, H.; Liu, Y.; Jing, Y.; Li, L.; Cheng, S.; Chen, G. Effect of vacuum microwave drying pretreatment on the production, characteristics, and quality of jujube powder. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 222, 117674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugumar, J.K.; Guha, P. Evaluation of the changes in physicochemical and functional characteristics of leaves of Solanum nigrum under different drying methods. Meas. Food 2025, 17, 100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luen, H.N.; Darius, A.F.; Yong, P.H.; Ng, Z.X. Chemometric analysis on the stability of bioactive compounds and antioxidant profile of plant-based foods subjected to digestion and different drying treatment. Food Biosci. 2025, 69, 106893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, P.; Yang, M.; Bobaru, F. Impact Mechanics and High-Energy Absorbing Materials: Review. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2008, 21, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Jia, N.; Zhu, L.; Jiang, W.; Tu, A.; Qin, K.; Yuan, X.; Li, J. Comparison of phenotypic and phytochemical profiles of 20 Lycium barbarum L. goji berry varieties during hot air-drying. Food Chem. X 2025, 27, 102436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Gong, Z.; Cao, Z.; Hou, F.; Cui, W.; Jia, F.; Jiao, J.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y. Mechanism of oxalic acid delaying browning of fresh-cut apples mediated by synergistic regulation of phenol metabolism and oxidative stress. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2025, 227, 113609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, B.B.; Gautam, S.; Sharma, A. Free phenolics and polyphenol oxidase (PPO): The factors affecting post-cut browning in eggplant (Solanum melongena). Food Chem. 2013, 139, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; He, Y.; Wang, F.; Wu, J.; Ci, Z.; Chen, L.; Xu, R.; Yang, M.; Lin, J.; Han, L.; et al. Microwave technology: A novel approach to the transformation of natural metabolites. Chin. Med. J. 2021, 16, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabelo, M.C.; Bang, W.Y.; Nair, V.; Alves, R.E.; Jacobo-Velázquez, D.A.; Sreedharan, S.; de Miranda, M.R.A.; Cisneros-Zevallos, L. UVC light modulates vitamin C and phenolic biosynthesis in acerola fruit: Role of increased mitochondria activity and ROS production. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papoutsis, K.; Pristijono, P.; Golding, J.B.; Stathopoulos, C.E.; Bowyer, M.C.; Scarlett, C.J.; Vuong, Q.V. Effect of vacuum-drying, hot air-drying and freeze-drying on polyphenols and antioxidant capacity of lemon (Citrus limon) pomace aqueous extracts. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 880–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, M.; Gil-Cortiella, M.; Peña-Neira, Á.; Gombau, J.; García-Roldán, A.; Cisterna, M.; Montané, X.; Fort, F.; Rozès, N.; Canals, J.M.; et al. Oxygen-induced enzymatic and chemical degradation kinetics in wine model solution of selected phenolic compounds involved in browning. Food Chem. 2025, 484, 144421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadidi, M.; Mumivand, H.; Nia, A.E.; Shayganfar, A.; Maggi, F. UV-A and UV-B combined with photosynthetically active radiation change plant growth, antioxidant capacity and essential oil composition of Pelargonium graveolens. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Gálvez, A.; Ah-Hen, K.; Chacana, M.; Vergara, J.; Martínez-Monzó, J.; García-Segovia, P.; Lemus-Mondaca, R.; Di Scala, K. Effect of temperature and air velocity on drying kinetics, antioxidant capacity, total phenolic content, colour, texture and microstructure of apple (var. Granny Smith) slices. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Hu, B.; Wu, J.; Yan, Y.; Luo, X.; Zhao, X.; Luo, Q. Electroporation-driven nutrient preservation and rehydration enhancement in blueberry drying via high-voltage electrostatic field pretreatment. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 223, 117763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Li, H.; Yi, J.; Sun, C.; Yu, Q.; Wen, R. Unravelling the effects of drying techniques on Porphyra yezoensis: Morphology, rehydration properties, metabolomic profile, and taste formation. Food Chem. 2025, 464, 141562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahoor, I.; Mir, T.A.; Ayoub, W.S.; Farooq, S.; Ganaie, T.A. Recent applications of microwave technology as novel drying of food—Review. Food Humanit. 2023, 1, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, M.; Mujumdar, A.S. Effects of vacuum and microwave freeze drying on microstructure and quality of potato slices. J. Food Eng. 2010, 101, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fundo, J.F.; Amaro, A.L.; Madureira, A.R.; Carvalho, A.; Feio, G.; Silva, C.L.M.; Quintas, M.A.C. Fresh-cut melon quality during storage: An NMR study of water transverse relaxation time. J. Food Eng. 2015, 167, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Yang, T.; Liu, Q.; Chen, X.; Cong, K.; Li, T.; Wu, C.; Fan, G.; Wafae, B.; Li, X. Influence of plasma-activated γ-aminobutyric acid on tissue browning and water migration in fresh-cut potato during storage. Food Biosci. 2023, 56, 103405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, S.; Huang, X.; Qin, Z.; Liu, T.; Tang, G.; Xie, X. Preparation of porous superabsorbent particles based on starch by supercritical CO2 drying and its water absorption mechanism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 258, 129102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Li, P.; Yin, P.; Cai, J.; Jin, B.; Zhang, H.; Lu, S. Bacterial community succession and volatile compound changes in Xinjiang smoked horsemeat sausage during fermentation. Food Res. Int. 2023, 174, 113656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Su, W.; Mu, Y.; Zhao, C. Correlation Between Microbial Diversity and Volatile Flavor Compounds of Suan zuo rou, a Fermented Meat Product From Guizhou, China. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 736525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Fan, W.; Xu, Y.; Cheng, P.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, X.; Hu, J. Characterization of volatile bitter off-taste compounds in Maotai-flavor baijiu (Chinese liquor). LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 217, 117363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Fu, J.; Lu, X. Hydrothermal decomposition of glucose and fructose with inorganic and organic potassium salts. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 119, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidek, T.; Devaud, S.; Robert, F.; Blank, I. Sugar Fragmentation in the Maillard Reaction Cascade: Isotope Labeling Studies on the Formation of Acetic Acid by a Hydrolytic β-Dicarbonyl Cleavage Mechanism. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 6667–6676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, H.; Kong, B.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Q. The succession and correlation of the bacterial community and flavour characteristics of Harbin dry sausages during fermentation. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 138, 110689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cao, Z.; Yu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, K. Effect of inoculating mixed starter cultures of Lactobacillus and Staphylococcus on bacterial communities and volatile flavor in fermented sausages. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2023, 12, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Drying Method | Fracture Force (g) | L* | a* | b* | ΔE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | 438.00 ± 17.08 b | 85.52 ± 1.24 c | −0.82 ± 0.04 a | 15.74 ± 0.21 a | / |

| HAD | 1667.78 ± 3.71 d | 74.64 ± 2.93 b | 3.45 ± 0.30 b | 21.55 ± 0.75 c | 13.05 |

| MD | 1009.18 ± 52.71 c | 41.66 ± 2.51 a | 8.76 ± 0.42 c | 17.76 ± 0.37 b | 44.94 |

| VFD | 196.71 ± 4.43 a | 76.57 ± 2.74 b | −0.77 ± 0.13 a | 15.04 ± 0.65 a | 8.98 |

| NAD | 1815.62 ± 0.50 e | 41.88 ± 0.93 a | 9.47 ± 0.48 d | 23.00 ± 0.91 d | 45.41 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tong, X.; Zhu, K.; Wu, S.; Liu, X.; Liu, C.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Chen, B.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Y.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Dried Water Bamboo Shoots Using Different Drying Methods: Physicochemical Properties and Flavor. Foods 2025, 14, 4357. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244357

Tong X, Zhu K, Wu S, Liu X, Liu C, Wang J, Liu H, Chen B, Wang X, Jiang Y, et al. Comparative Analysis of Dried Water Bamboo Shoots Using Different Drying Methods: Physicochemical Properties and Flavor. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4357. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244357

Chicago/Turabian StyleTong, Xiaoyang, Kai Zhu, Songheng Wu, Xiaomei Liu, Chenxia Liu, Jun Wang, Hongru Liu, Bingjie Chen, Xiao Wang, Yingdong Jiang, and et al. 2025. "Comparative Analysis of Dried Water Bamboo Shoots Using Different Drying Methods: Physicochemical Properties and Flavor" Foods 14, no. 24: 4357. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244357

APA StyleTong, X., Zhu, K., Wu, S., Liu, X., Liu, C., Wang, J., Liu, H., Chen, B., Wang, X., Jiang, Y., Qiao, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Comparative Analysis of Dried Water Bamboo Shoots Using Different Drying Methods: Physicochemical Properties and Flavor. Foods, 14(24), 4357. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244357