Development of a Cost-Effective, Heme-Tolerant Bovine Muscle Cell for Cultivated Meat Production

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and Media

2.2. Preparation and Quantification of the Heme Extract

2.3. Cell Adaptation to High-Heme Conditions

2.4. Cell Growth and Viability Assay

2.5. Construction and Cloning of pLKO.1-TRC shRNA Vectors

2.6. Lentiviral-Mediated shRNA Knockdown

2.7. RNA Isolation and RT–PCR

2.8. Western Blotting

2.9. Determination of Intracellular ROS Generation

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Optimization of Culture Condition for the BRMC-F2401 Bovine Muscle Cell Line

3.2. Derivation of Heme-Adapted BRMCs by Continuous Culture

3.3. RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq) Reveals Differentially Expressed Genes in Heme-Adapted BRMC-Ha Cells

3.4. Confirmation of the Gene Expression Changes in the BRMC-Ha Based on Heme Detoxification

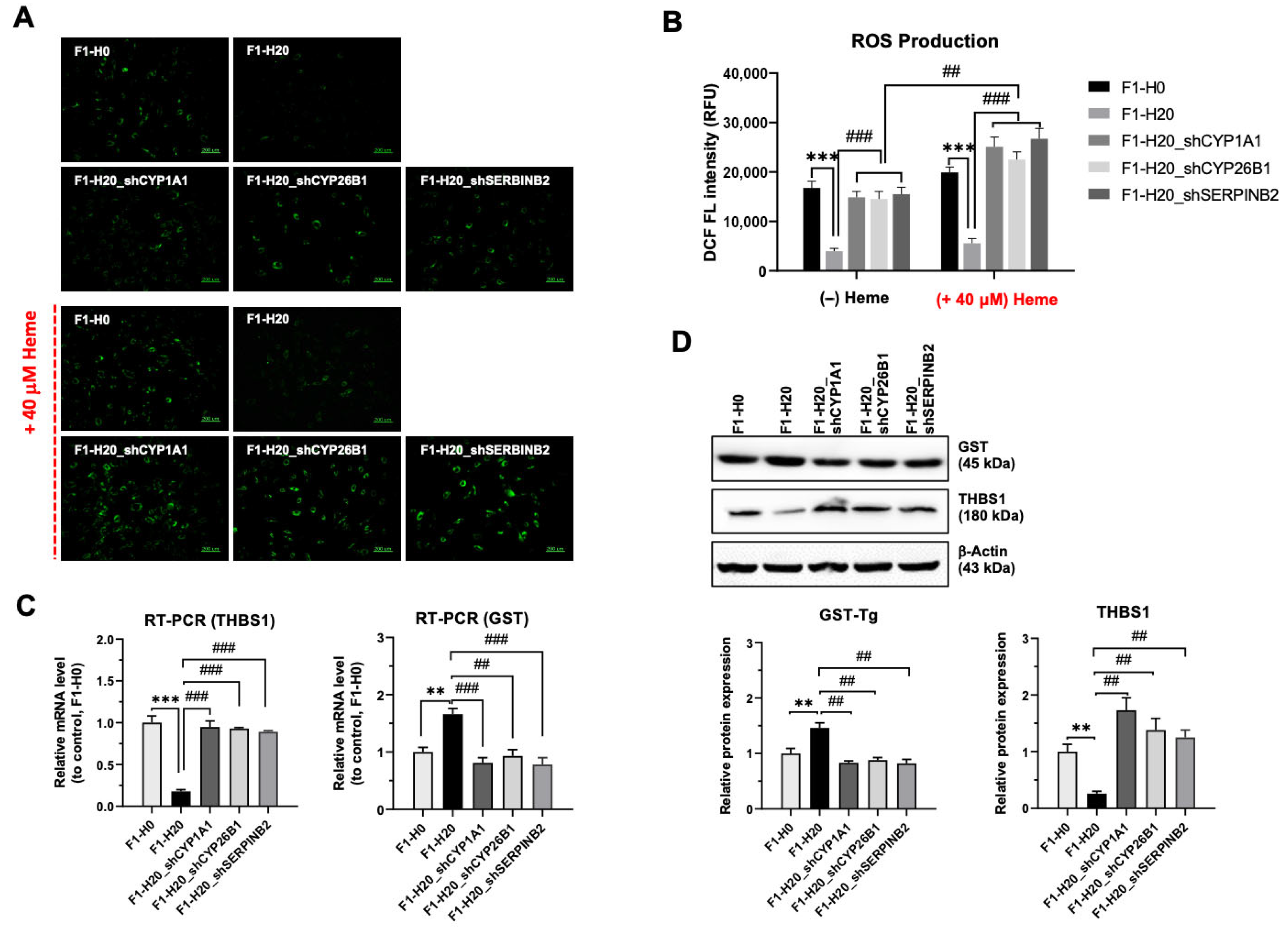

3.5. Upregulated CYP1A1, CYP26B1, and SERPINB2 Are Required for the Adaptation of Heme Toxicity in the BRMC-Ha Cells

3.6. BMRC-Ha Cells Attenuate Heme-Mediated ROS Generation via the Upregulation of Genes Involved in the Detoxification Process

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fraeye, I.; Kratka, M.; Vandenburgh, H.; Thorrez, L. Sensorial and Nutritional Aspects of Cultured Meat in Comparison to Traditional Meat: Much to Be Inferred. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, Y.J.; Kim, M.; You, S.K.; Shin, S.K.; Chang, J.; Choi, H.J.; Jeong, W.Y.; Lee, M.E.; Hwang, D.H.; Han, S.O. Animal-free heme production for artificial meat in Corynebacterium glutamicum via systems metabolic and membrane engineering. Metab. Eng. 2021, 66, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proulx, A.K.; Reddy, M.B. Iron bioavailability of hemoglobin from soy root nodules using a Caco-2 cell culture model. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 1518–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swain, J.H.; Glosser, L.D. A Porcine-Derived Heme Iron Powder Restores Hemoglobin in Anemic Rats. Nutrients 2024, 16, 4029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.; Wu, X.; Wu, P.; Lu, X.; Wang, Q.; Lin, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhou, J.; Yu, Y.; Lu, H. High-level expression of leghemoglobin in Kluyveromyces marxianus by remodeling the heme metabolism pathway. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1329016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.I.; Park, J.; Kim, P. Heme Derived from Corynebacterium glutamicum: A Potential Iron Additive for Swine and an Electron Carrier Additive for Lactic Acid Bacterial Culture. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 27, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Bandyopadhyay, U. Free heme toxicity and its detoxification systems in human. Toxicol. Lett. 2005, 157, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Develi-Is, S.; Bekpinar, S.; Kalaz, E.B.; Evran, B.; Unlucerci, Y.; Gulluoglu, M.; Uysal, M. The protection by heme oxygenase-1 induction against thioacetamide-induced liver toxicity is associated with changes in arginine and asymmetric dimethylarginine. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2013, 31, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Cederbaum, A.I.; Nieto, N. Heme oxygenase-1 protects HepG2 cells against cytochrome P450 2E1-dependent toxicity. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 36, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagener, F.A.; Dankers, A.C.; van Summeren, F.; Scharstuhl, A.; van den Heuvel, J.J.; Koenderink, J.B.; Pennings, S.W.; Russel, F.G.; Masereeuw, R. Heme Oxygenase-1 and breast cancer resistance protein protect against heme-induced toxicity. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 2698–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manikanta; NaveenKumar, S.K.; Thushara, R.M.; Hemshekhar, M.; Sumedini, M.L.; Sunitha, K.; Kemparaju, K.; Girish, K.S. Counteraction of unconjugated bilirubin against heme-induced toxicity in platelets. Thromb. Res. 2024, 244, 109199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsushita, K.; Toyoda, T.; Akane, H.; Morikawa, T.; Ogawa, K. A 13-week subchronic toxicity study of heme iron in SD rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2023, 175, 113702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, C.J.; Pires, I.S.; Jani, V.; Gopal, S.; Palmer, A.F.; Cabrales, P. Apohemoglobin-haptoglobin complex alleviates iron toxicity in mice with β-thalassemia via scavenging of cell-free hemoglobin and heme. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 156, 113911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Reyes, S.; Orozco-Ibarra, M.; Guzman-Beltran, S.; Molina-Jijon, E.; Massieu, L.; Pedraza-Chaverri, J. Neuroprotective role of heme-oxygenase 1 against iodoacetate-induced toxicity in rat cerebellar granule neurons: Role of bilirubin. Free Radic. Res. 2009, 43, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabibzadeh, N.; Estournet, C.; Placier, S.; Perez, J.; Bilbault, H.; Girshovich, A.; Vandermeersch, S.; Jouanneau, C.; Letavernier, E.; Hammoudi, N.; et al. Plasma heme-induced renal toxicity is related to a capillary rarefaction. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrivergaard, S.; Rasmussen, M.K.; Therkildsen, M.; Young, J.F. Bovine Satellite Cells Isolated after 2 and 5 Days of Tissue Storage Maintain the Proliferative and Myogenic Capacity Needed for Cultured Meat Production. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.A.; Oh, S.; Park, G.; Park, S.; Park, Y.; Choi, H.; Kim, M.; Choi, J. Characteristics of bovine muscle satellite cell from different breeds for efficient production of cultured meat. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2024, 66, 1257–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stout, A.J.; Arnett, M.J.; Chai, K.; Guo, T.; Liao, L.; Mirliani, A.B.; Rittenberg, M.L.; Shub, M.; White, E.C.; Yuen, J.S.K., Jr.; et al. Immortalized Bovine Satellite Cells for Cultured Meat Applications. ACS Synth. Biol. 2023, 12, 1567–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simsa, R.; Yuen, J.; Stout, A.; Rubio, N.; Fogelstrand, P.; Kaplan, D.L. Extracellular Heme Proteins Influence Bovine Myosatellite Cell Proliferation and the Color of Cell-Based Meat. Foods 2019, 8, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaere, J.; De Winne, A.; Dewulf, L.; Fraeye, I.; Soljic, I.; Lauwers, E.; de Jong, A.; Sanctorum, H. Improving the Aromatic Profile of Plant-Based Meat Alternatives: Effect of Myoglobin Addition on Volatiles. Foods 2022, 11, 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Xie, R. Knockdown of THBS1 inhibits inflammatory damage and oxidative stress in in vitro pneumonia model by regulating NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Allergol. Et Immunopathol. 2025, 53, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstone, H.M.; Stegeman, J.J. A revised evolutionary history of the CYP1A subfamily: Gene duplication, gene conversion, and positive selection. J. Mol. Evol. 2006, 62, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Shi, Z.D.; Pang, K.; Hao, L.; Wang, W.; Han, C.H. Retinoic acid metabolism related gene CYP26B1 promotes tumor stemness and tumor microenvironment remodeling in bladder cancer. J. Cancer 2025, 16, 2476–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.; Clarke, S. Influence of microRNA on the maintenance of human iron metabolism. Nutrients 2013, 5, 2611–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozzelino, R.; Jeney, V.; Soares, M.P. Mechanisms of cell protection by heme oxygenase-1. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2010, 50, 323–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seng, S.; Avraham, H.; Birrane, G.; Jiang, S.; Li, H.; Katz, G.; Bass, C.; Zagozdzon, R.; Avraham, S. NRP/B mutations impair Nrf2-dependent NQO1 induction in human primary brain tumors. Oncogene 2009, 28, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, M.; Numazawa, S.; Yoshida, T. Redox regulation of the transcriptional repressor Bach1. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2005, 38, 1344–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Ding, Z.; Xiao, X.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, Q. A novel mechanism for A-to-I RNA-edited CYP1A1 in promoting cancer progression in NSCLC. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2025, 30, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallet, R.T.; Burtscher, J.; Pialoux, V.; Pasha, Q.; Ahmad, Y.; Millet, G.P.; Burtscher, M. Molecular mechanisms of high-altitude acclimatization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutecki, S.; Lesniewska-Bocianowska, A.; Chmielewska, K.; Matuszewska, J.; Naumowicz, E.; Uruski, P.; Radziemski, A.; Mikula-Pietrasik, J.; Tykarski, A.; Ksiazek, K. Serum starvation-based method of ovarian cancer cell dormancy induction and termination in vitro. Biol. Methods Protoc. 2023, 8, bpad029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanko, V.P.; Rohrer, J.S. Determination of amino acids in cell culture and fermentation broth media using anion-exchange chromatography with integrated pulsed amperometric detection. Anal. Biochem. 2004, 324, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwuchukwu, G.A.; Gökçek, D.; Özdemir, Z. Myogenic Regulator Genes Responsible For Muscle Development in Farm Animals. Black Sea J. Agric. 2024, 7, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Hernández, J.M.; García-González, E.G.; Brun, C.E.; Rudnicki, M.A. The myogenic regulatory factors, determinants of muscle development, cell identity and regeneration. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017, 72, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammit, P.S. Function of the myogenic regulatory factors Myf5, MyoD, Myogenin and MRF4 in skeletal muscle, satellite cells and regenerative myogenesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017, 72, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyen, N.T.; Van Cuong, D.; Thuy, P.D.; Son, L.H.; Ngan, N.T.; Quang, N.H.; Tuan, N.D.; Hwang, I.-H. A comparative study on the adipogenic and myogenic capacity of muscle satellite cells, and meat quality characteristics between Hanwoo and Vietnamese yellow steers. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2023, 43, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haines, D.D.; Tosaki, A. Heme degradation in pathophysiology of and countermeasures to inflammation-associated disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Gene_ID | Transcript_ID | Gene_Symbol | Description | BRMC-F1-H20/ | BRMC-F1-H20/ | BRMC-F1-H20/ | BRMC-F1-H20/ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRMC-F1-H0.fc | BRMC-F1-H0.logCPM | BRMC-F1-H0.raw.pval | BRMC-F1-H0.bh.pval | |||||

| 1 | 505184 | NM_001192051 | SERPINB2 | serpin family B member 2 | 310.384251 | 7.122725 | 2.14E−163 | 1.19E−159 |

| 2 | 281309 | NM_001206637 | MMP3 | matrix metallopeptidase 3 | 382.803057 | 6.166615 | 7.78E−152 | 3.24E−148 |

| (stromelysin 1, progelatinase) | ||||||||

| 3 | 112441463 | XM_024975704 | LOC112441463 | interstitial collagenase-like | 66.893402 | 8.918018 | 4.36E−123 | 9.08E−120 |

| 4 | 281615 | NM_174239 | ALDH1A1 | aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 family member A1 | −46.095674 | 6.782363 | 5.11E−104 | 6.08E−101 |

| 5 | 281210 | NM_174077, | GPX3 | glutathione peroxidase 3 | −11.536539 | 3.511371 | 1.17E−44 | 1.30E−42 |

| NR_138142 | ||||||||

| No. | Gene_ID | Transcript_ID | Gene_Symbol | Term_name | BRMC-F1-H20/ | BRMC-F1-H20/ | BRMC-F1-H20/ | BRMC-F1-H20/ |

| BRMC-F1-H0.fc | BRMC-F1-H0.logCPM | BRMC-F1-H0.raw.pval | BRMC-F1-H0.bh.pval | |||||

| 6 | 538861 | XM_002686859 | STEAP4 | heme binding | 54.313319 | 2.768096 | 3.27E−63 | 9.54E−61 |

| 7 | 282870 | XM_002696635, | CYP1A1 | heme binding | 15.99953 | 3.652174 | 3.27E−52 | 5.39E−50 |

| XM_005222018 | ||||||||

| 8 | 510406 | XM_002707809 | CYP2J2 | heme binding | −12.126655 | 2.071745 | 5.32E−35 | 3.64E−33 |

| 9 | 541302 | NM_001076267, | CYP2R1 | heme binding | −4.60079 | 3.860629 | 4.36E−22 | 1.27E−20 |

| XM_005216056, | ||||||||

| XM_005216057, | ||||||||

| XM_005216059, | ||||||||

| XM_010812511, | ||||||||

| XM_024975514 | ||||||||

| 10 | 282211 | NM_174529, | CYP2D14 | heme binding | −2.224938 | 3.59268 | 1.95E−07 | 1.28E−06 |

| XM_010805743 |

| Source | term_id | term_name | adjusted_p_value | intersection_size | Gene_ID | Transcript_ID | Gene_Symbol | BRMC-F1-H20/ | BRMC-F1-H20/ | BRMC-F1-H20/ | BRMC-F1-H20/ | N_BRMC-F1-H0 | N_BRMC-F1-H20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRMC-F1-H0.fc | BRMC-F1-H0.logCPM | BRMC-F1-H0.raw.pval | BRMC-F1-H0.bh.pval | ||||||||||

| GO:MF | GO:0020037 | heme binding | 0.76595423 | 11 | 538861 | XM_002686859 | STEAP4 | 54.313319 | 2.768096 | 3.27E−63 | 9.54E−61 | 0.312384 | 3.831677 |

| GO:MF | GO:0020037 | heme binding | 0.76595423 | 11 | 282870 | XM_002696635, | CYP1A1 | 15.99953 | 3.652174 | 3.27E−52 | 5.39E−50 | 1.304012 | 4.616819 |

| XM_005222018 | |||||||||||||

| GO:MF | GO:0020037 | heme binding | 0.76595423 | 11 | 282022 | NM_001105323, XM_024998320, XM_024998321, XM_024998322 | PTGS1 | 11.120892 | 5.580917 | 2.16E−50 | 3.21E−48 | 3.151377 | 6.471008 |

| GO:MF | GO:0020037 | heme binding | 0.76595423 | 11 | 510406 | XM_002707809 | CYP2J2 | −12.126655 | 2.071745 | 5.32E−35 | 3.64E−33 | 3.133145 | 0.71297 |

| GO:MF | GO:0020037 | heme binding | 0.76595423 | 11 | 282021 | NM_174444, XM_015474114, XM_015474115 | PTGIS | −5.568505 | 4.904741 | 1.43E−28 | 6.84E−27 | 5.69454 | 3.33898 |

| GO:MF | GO:0020037 | heme binding | 0.76595423 | 11 | 541302 | NM_001076267, | CYP2R1 | −4.60079 | 3.860629 | 4.36E−22 | 1.27E−20 | 4.635735 | 2.628638 |

| XM_005216056, | |||||||||||||

| XM_005216057, | |||||||||||||

| XM_005216059, | |||||||||||||

| XM_010812511, | |||||||||||||

| XM_024975514 | |||||||||||||

| GO:MF | GO:0020037 | heme binding | 0.76595423 | 11 | 282023 | NM_174445 | PTGS2 | 3.943702 | 5.65262 | 4.19E−20 | 1.07E−18 | 4.41456 | 6.342817 |

| GO:MF | GO:0020037 | heme binding | 0.76595423 | 11 | 540573 | NM_001192745 | STC2 | −5.074452 | 1.717307 | 1.05E−17 | 2.20E−16 | 2.69734 | 1.056233 |

| GO:BP | GO:0015886 | heme transport | 0.27742268 | 2 | 511097 | NM_001079585 | SLC46A1 | 4.211165 | 1.922604 | 1.03E−14 | 1.63E−13 | 1.282115 | 2.814889 |

| GO:BP | GO:0006784 | heme A biosynthetic process | 0.23434953 | 3 | 534286 | NM_001101154, XM_024982845, XM_024982846 | ALAS1 | −2.442743 | 6.471196 | 7.66E−10 | 7.02E−09 | 6.987339 | 5.715116 |

| GO:BP | GO:0006784 | heme A biosynthetic process | 0.23434953 | 3 | 517811 | NM_001076861, XM_024985622, XM_024985623 | COX15 | 2.25615 | 4.449531 | 5.34E−08 | 3.83E−07 | 3.846963 | 4.964013 |

| GO:BP | GO:0006784 | heme A biosynthetic process | 0.23434953 | 3 | 281158 | NM_174054 | FECH | 2.297128 | 3.517908 | 8.28E−08 | 5.75E−07 | 2.985136 | 4.078452 |

| GO:MF | GO:0020037 | heme binding | 0.76595423 | 11 | 282211 | NM_174529, | CYP2D14 | −2.224938 | 3.59268 | 1.95E−07 | 1.28E−06 | 4.139594 | 3.082574 |

| XM_010805743 | |||||||||||||

| GO:BP | GO:0097037 | heme export | 0.26278276 | 1 | 533317 | NM_001206019, XM_010813570, XR_003029610 | FLVCR1 | 2.074857 | 4.163325 | 1.20E−06 | 6.93E−06 | 3.657981 | 4.650661 |

| GO:MF | GO:0020037 | heme binding | 0.76595423 | 11 | 504769 | NM_001075173, | CYP2B6 | −2.778364 | −0.648631 | 0.00036633 | 0.00129398 | 0.934511 | 0.407831 |

| XM_005218914 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oh, Y.O.; Yu, C.W.; Cha, M.J.; Lee, E.J.; Kim, P.; Chang, S. Development of a Cost-Effective, Heme-Tolerant Bovine Muscle Cell for Cultivated Meat Production. Foods 2025, 14, 4348. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244348

Oh YO, Yu CW, Cha MJ, Lee EJ, Kim P, Chang S. Development of a Cost-Effective, Heme-Tolerant Bovine Muscle Cell for Cultivated Meat Production. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4348. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244348

Chicago/Turabian StyleOh, Yun Ok, Chae Won Yu, Min Jeong Cha, Eun Ji Lee, Pil Kim, and Suhwan Chang. 2025. "Development of a Cost-Effective, Heme-Tolerant Bovine Muscle Cell for Cultivated Meat Production" Foods 14, no. 24: 4348. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244348

APA StyleOh, Y. O., Yu, C. W., Cha, M. J., Lee, E. J., Kim, P., & Chang, S. (2025). Development of a Cost-Effective, Heme-Tolerant Bovine Muscle Cell for Cultivated Meat Production. Foods, 14(24), 4348. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244348