Advances and Challenges in Smart Packaging Technologies for the Food Industry: Trends, Applications, and Sustainability Considerations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Evolution of Food Packaging

2.1. Historical Development of Packaging Technologies

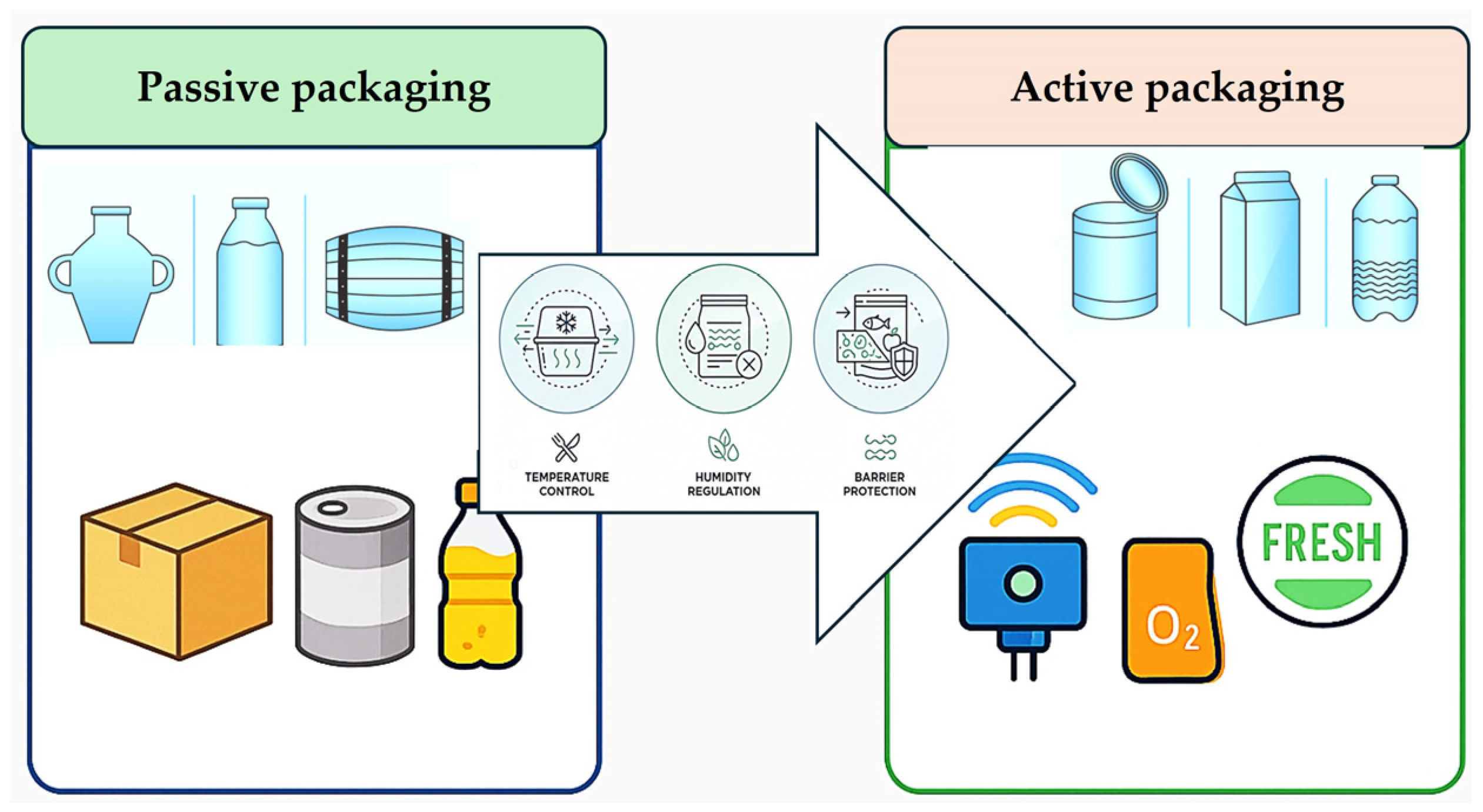

2.2. Transition from Passive to Active Packaging

3. Classification of Packaging Systems

3.1. Passive Packaging Systems

3.2. Active Packaging Systems

3.3. Intelligent Packaging Systems

4. Materials and Technologies for Smart Packaging

4.1. Innovative Packaging Materials

4.1.1. Biodegradable and Sustainable Materials

4.1.2. Emerging Nanomaterials: Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and Quantum Materials for Smart Packaging

4.2. Embedded Sensing Technologies

4.2.1. Chemical Sensors for Food Quality

4.2.2. Temperature and Humidity Sensors

4.3. Benchmarks and Comparative Evaluation of Smart Food Packaging Systems

5. Applications of Smart Packaging in the Food Industry

5.1. Shelf-Life Extension

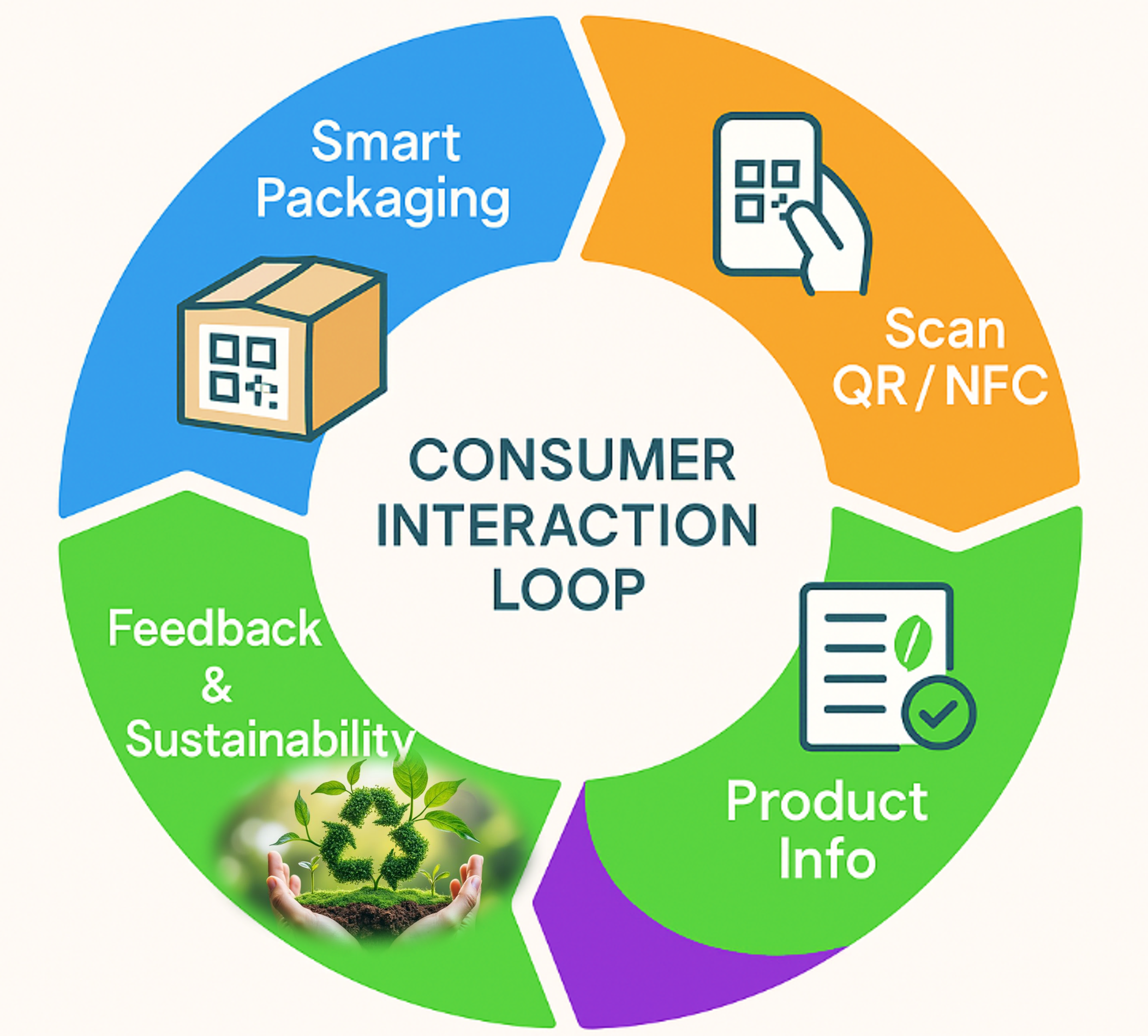

5.2. Consumer Interaction and Engagement

6. Impact of Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Nanomaterials on Food Safety and Shelf-Life

- Antibacterial mechanisms and packaging efficacy

- 2.

- Antioxidant mechanisms and oxidative stability

7. New Directions and Innovations for the Development of Sustainable Food Packaging Systems

7.1. Integration of IoT and AI in Next-Generation Smart Packaging

7.2. Advanced Strategies for Sustainable Food Packaging Development

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peng, W.; Peng, H. Green food packaging industry to explore and analyze. Int. J. Nat. Resour. Environ. Stud. 2024, 3, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassoun, A. Food sustainability 4.0: Harnessing fourth industrial revolution technologies for sustainable food systems. Discov. Food 2025, 5, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, M.; Rauf, Z.; Fatima, S.; Ullah, A. Lignin-derived bionanocomposites as functional food packaging materials. Sustain. Food Technol. 2024, 2, 945–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldhans, C.; Albrecht, A.; Ibald, R.; Wollenweber, D.; Sy, S.J.; Kreyenschmidt, J. Temperature control and data exchange in food supply chains: Applicability of digitalized time–temperature indicators for cold chain optimization. J. Packag. Technol. Res. 2024, 8, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, E.; Mirosa, M.; Bremer, P. A systematic review of consumer perceptions of smart packaging technologies for food. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, N.; Trimingham, R.; Storer, I. Understanding the views of the UK food packaging supply chain to support a move to circular economy systems. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2019, 32, 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-López, M.E.; Calva-Estrada, S.J.; Gradilla-Hernández, M.S.; Barajas-Álvarez, P. Current trends in biopolymers for food packaging: A review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1225371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, L.; Puzko, S.; Lavrenenko, V.; Gernego, I. Fostering sustainable packaging industry: Global trends and challenges. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 13, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, S.; Chanda, S.; Bhaumik, A. Active and intelligent packaging technologies: An aspect of food safety management. Int. J. Curr. Res. Rev. 2022, 14, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, M.; Chellasudheer, M.; Manojkumar, V.; Arasu, J.; Mathesh, T.A. New advances in smart packaging production methods. Int. J. Trendy Res. Eng. Technol. 2023, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X. Blockchain-enabled smart packaging: Enhancing food traceability and consumer confidence in the Chinese food industry. Front. Soc. Sci. Technol. 2023, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, M.M.; Mahmoudpour, M. Function and application of some active and antimicrobial packaging in the food industry: A review. J. Microbiota 2024, 1, e144616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamri, M.; Bhattacharya, T.; Boukid, F.; Chentir, I.; Dib, A.L.; Das, D.; Djenane, D.; Gagaoua, M. Nanotechnology as a processing and packaging tool to improve meat quality and safety. Foods 2021, 10, 2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, A.; Ibald, R.; Raab, V.; Reichstein, W.; Haarer, D.; Kreyenschmidt, J. Implementation of time–temperature indicators to improve temperature monitoring and support dynamic shelf life in meat supply chains. J. Packag. Technol. Res. 2020, 4, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceballos, R.L.; Ochoa-Yepes, O.; Goyanes, S.; Bernal, C.; Famá, L. Effect of yerba mate extract on the performance of starch films obtained by extrusion and compression molding as active and smart packaging. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 239, 116495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yüceer, M.; Caner, C. Intelligent packaging and applications in the food industry. J. Food Feed Sci. Technol. 2023, 30, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, P.R.; Di Giorgio, L.; Musso, Y.S.; Mauri, A.N. Recent developments in smart food packaging focused on biobased and biodegradable polymers. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 630393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazanfarzadeh, Z.; Masek, A.; Chakraborty, S.; Kumaravel, V. Development of brewer’s spent grain-derived bionanocomposites through a multiproduct biorefinery approach for food packaging. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 220, 119226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhai, X.; Zou, X.; Shi, J.; Huang, X.; Li, Z.; Gong, Y.; Holmes, M.; Povey, M.; Xiao, J. Bilayer pH-sensitive colorimetric films with light-blocking ability and electrochemical writing property: Application in monitoring crucian spoilage in smart packaging. Food Chem. 2021, 336, 127634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Brahma, S.; Mackay, J.; Cao, C.; Aliakbarian, B. The role of smart packaging systems in the food supply chain. J. Food Sci. 2020, 85, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Almeida, A.P.; de Albuquerque, T.L. Innovations in food packaging: From bio-based materials to smart packaging systems. Processes 2024, 12, 2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runtuk, J.K.; Maukar, A.L. Analysis and framework for agricultural supply chain improvement: A case study of California papaya in Cikarang. J. Sist. Manaj. Ind. 2019, 3, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E. Development of hybrid food products safety control technology and green supply chain management (GSCM): Theory and design. Alanya Acad. Rev. 2019, 3, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, M.S.; Qasem, A.A.; Mohamed, A.A.; Hussain, S.; Ibraheem, M.A.; Shamlan, G.; Hesham, A.A.; Qasha, A.S. Food packaging’s materials: A food safety perspective. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 4490–4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, G.; Ahad, M.A.; Casalino, G. A comprehensive review of blockchain technology: Underlying principles and historical background with future challenges. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 9, 100344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanciu, A.C. Smart packaging main trends. Ovidius Univ. Ann. Econ. Sci. Ser. 2024, 24, 443–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, M.; Malagas, K.; Nomikos, S.; Papapostolou, A.; Vlassas, G. An overview of the impact of the food sector “intelligent packaging” and “smart packaging”. Eur. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 2023, 15, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, P.; Schmid, M. Intelligent packaging in the food sector: A brief overview. Foods 2019, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tas, C.E.; Hendessi, S.; Baysal, M.; Unal, S.; Cebeci, F.C.; Menceloglu, Y.Z.; Unal, H. Halloysite nanotubes/polyethylene nanocomposites for active food packaging materials with ethylene scavenging and gas barrier properties. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2017, 10, 789–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yang, W.; Xia, Y.; Xue, W.; Wu, H.; Li, Z.; Zhang, F.; Qiu, B.; Fu, C. Properties and applications of intelligent packaging indicators for food spoilage. Membranes 2022, 12, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Li, Z.; Shi, J.; Huang, X.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, D.I.; Zou, X.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Holmes, M.; et al. A colorimetric hydrogen sulfide sensor based on gellan gum–silver nanoparticles bionanocomposite for monitoring meat spoilage in intelligent packaging. Food Chem. 2019, 290, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Realini, C.E.; Marcos, B. Active and intelligent packaging systems for a modern society. Meat Sci. 2014, 98, 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, D.; Cheung, W.M. Smart packaging: Opportunities and challenges. Procedia CIRP 2018, 72, 1022–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, M.R.; Ahmad, I.; Phang, S.W. Starch/polyaniline biopolymer film as potential intelligent food packaging with colourimetric ammonia sensor. Polymers 2022, 14, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmaus, A.L.; Osborn, R.; Krishan, M. Scientific advances and challenges in safety evaluation of food packaging materials: Workshop proceedings. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 98, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirpan, A.; Djalal, M.; Ainani, A.F. A simple combination of active and intelligent packaging based on garlic extract and indicator solution in extending and monitoring meat quality stored at cold temperature. Foods 2022, 11, 1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigauri, I.; Palazzo, M. Intelligent packaging as a marketing tool: Are digital technologies reshaping packaging? Agora Int. J. Econ. Sci. 2023, 17, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yele, S.; Litoriya, R. Blockchain-based secure dining: Enhancing safety, transparency, and traceability in food consumption environments. Blockchain Res. Appl. 2024, 5, 100187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Gutub, A.; Nayyar, A.; Khan, M.K. Redefining food safety traceability system through blockchain: Findings, challenges, and open issues. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 21243–21277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi-Firoozjah, R.; Yousefi, S.; Heydari, M.; Seyedfatehi, F.; Jafarzadeh, S.; Mohammadi, R.; Rouhi, M.; Garavand, F. Application of red cabbage anthocyanins as pH-sensitive pigments in smart food packaging and sensors. Polymers 2022, 14, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeredo, H.M.; Correa, D.S. Smart choices: Mechanisms of intelligent food packaging. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 932–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, S.; Won, K. Self-powered flexible oxygen sensors for intelligent food packaging. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2021, 29, 100713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Debbarma, R.; Nasrin, N.; Khan, T.; Taj, S.; Bhuyan, T. Recent advances in packaging materials for food products. Food Bioeng. 2024, 3, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadiji, T.; Pathare, P.B. Technological advancements in food processing and packaging. Processes 2023, 11, 2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, Y.; Pelegrín, C.J.; Ramos, M.; Jiménez, A.; Garrigós, M.C. Use of herbs and their bioactive compounds in active food packaging. In Aromatic Herbs in Food; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 323–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabretta, M.M.; Gregucci, D.; Desiderio, R.; Michelini, E. Colorimetric paper sensor for food spoilage based on biogenic amine monitoring. Biosensors 2023, 13, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitz, R.; Walker, T.; Charlebois, S.; Music, J. Food packaging during the COVID-19 pandemic: Consumer perceptions. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 434–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.Z.; Shi, X.; Yang, H.; Abbas, J.; Chen, J. The impact of interpretive packaged food labels on consumer purchase intention. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirpan, A.; Iqbal, M.; Yumeina, D.; Prahesti, K.I.; Djalal, M.; Syarifuddin, A.; Bahmid, N.A.; Bastian, F.; Salengke, S.; Suryono, S. Smart packaging for chicken meat quality: Absorbent food pad and Whatman paper applications. Indones. Food Sci. Technol. J. 2023, 7, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Lee, S. Development of essential oil-containing antimicrobial and deodorizing nanofibrous membranes for sanitary napkin applications. J. Ind. Text. 2024, 54, 15280837241248838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, E.; Campardelli, R.; Pettinato, M.; Perego, P. Innovations in smart packaging concepts for food: An extensive review. Foods 2020, 9, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazzola, P.; Pavione, E.; Barge, A.; Fassio, F. Using the transparency of supply chain powered by blockchain to improve sustainability relationships with stakeholders in the food sector: The case study of Lavazza. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, M.; Ferreira, J.C. Beyond traceability: Decentralised identity and digital twins for verifiable product identity in agri-food supply chains. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontominas, M.G.; Badeka, A.V.; Kosma, I.S.; Nathanailides, C.I. Recent developments in seafood packaging technologies. Foods 2021, 10, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushani, K.G.; Rathnasinghe, N.L.; Katuwawila, N.; Jayasinghe, R.A.; Nilmini, A.H.L.R.; Priyadarshana, G. Trends in smart packaging technologies for sustainable monitoring of food quality and safety. Int. J. Res. Innov. Appl. Sci. 2022, 7, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, S.; Bang, Y.J.; Rhim, J.W. Antibacterial LDPE/GSE/Mel/ZnONP composite film-coated wrapping paper for convenience food packaging application. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2019, 22, 100421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanth, S.; Feng, S.; Patra, D.; Pradhan, A.K. Linking microbial contamination to food spoilage and food waste: The role of smart packaging, spoilage risk assessments, and date labeling. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1198124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatlawande, A.R.; Ghatge, P.U.; Shinde, G.U.; Anushree, R.K.; Patil, S.D. Unlocking the future of smart food packaging: Biosensors, IoT, and nanomaterials. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 33, 1075–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, A.M.; Zhang, W.; Abedini, A.; Khezerlou, A.; Shariatifar, N.; Assadpour, E.; Zhang, F.; Jafari, S.M. Intelligent packaging systems for the quality and safety monitoring of meat products: From lab scale to industrialization. Food Control 2024, 160, 110359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, W.; Lim, S. A review on gas indicators and sensors for smart food packaging. Foods 2024, 13, 3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palanisamy, Y.; Kadirvel, V.; Ganesan, N.D. Recent technological advances in food packaging: Sensors, automation, and application. Sustain. Food Technol. 2024, 3, 161–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yar, M.S.; Ibeogu, I.H.; Regmi, A.; Zhang, N.; Li, C. Advances in intelligent time-temperature indicators for cold chain monitoring: Mechanisms, challenges, and applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 163, 105128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barik, M.; BhagyaRaj, G.V.S.; Dash, K.K.; Shams, R. A thorough evaluation of chitosan-based packaging film and coating for food product shelf-life extension. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 16, 101164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panzaru, C.; Radu-Rusu, R.M.; Dolis, M.G.; Nistor, M.; Maciuc, V.; Davidescu, M.A. Contributions to the study of milk quality from various cattle breeds. SCSCC6 2024, 25, 393–401. Available online: https://pubs.ub.ro/uploads/articole/5685/CSCC6202404V04S01A0005.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Sobhan, A.; Hossain, A.; Wei, L.; Muthukumarappan, K.; Ahmed, M. IoT-enabled biosensors in food packaging: A breakthrough in food safety for monitoring risks in real time. Foods 2025, 14, 1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abekoon, T.; Buthpitiya, B.L.S.K.; Sajindra, H.; Samarakoon, E.R.J.; Jayakody, J.A.D.C.A.; Kantamaneni, K.; Rathnayake, U. A comprehensive review to evaluate the synergy of intelligent food packaging with modern food technology and artificial intelligence field. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnwal, A.; Rauf, A.; Jassim, A.Y.; Selvaraj, M.; Al-Tawaha, A.R.M.S.; Kashyap, P.; Kumar, D.; Malik, T. Advanced starch-based films for food packaging: Innovations in sustainability and functional properties. Food Chem. X 2025, 29, 102662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, K.A.; Quested, T.E.; Lanctuit, H.; Zimmermann, D.; Espinoza-Orias, N.; Roulin, A. Nutrition in the bin: A nutritional and environmental assessment of food wasted in the UK. Front. Nutr. 2018, 5, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oboturova, N.; Povetkin, S.; Nikulnikova, N.; Lazareva, N.; Klopova, A.; Lyubchanskiy, N.; Sukhanova, E.; Lebedeva, N. Upcycling agricultural byproducts into eco-friendly food packaging. Potravinar. Slovak J. Food Sci. 2024, 18, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halim-Lim, S.A.; Baharuddin, A.A.; Cherrafi, A.; Ilham, Z.; Jamaludin, A.A.; David, W.; Sodhi, H.S. Digital innovations in the post-pandemic era towards safer and sustainable food operations: A mini-review. Front. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 2, 1057652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, M.; Backhaus, J. Development of an irreversible hydrochromic ink for smart packaging. J. Print Media Technol. Res. 2020, 9, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Wang, F.; He, Z.; Tang, H.; Li, H.; Hou, J.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, L. Development and characterization of active packaging based on chitosan/chitin nanofibers incorporated with scallion flower extract for fresh-cut bananas. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242, 125045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A.U.; Rathi, P.; Beshai, H.; Sarabha, G.K.; Deen, M.J. Fruit quality monitoring with smart packaging. Sensors 2021, 21, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehra, A.; Wani, S.M.; Bhat, T.A.; Jan, N.; Hussain, S.Z.; Naik, H.R. Preparation of biodegradable chitosan packaging film based on ZnO, CaCl2, nanoclay and PEG with thyme oil. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 217, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyrwa, J.; Barska, A. Innovations in the food packaging market: Active packaging. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2017, 243, 1681–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A. Do date codes cause food waste? Smart packaging might tackle the problem. J. Food Bioact. 2023, 24, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuma, H.S.; Yugiani, P.; Himana, A.I.; Aziz, A. Reflections on food security and smart packaging. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 87–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kühn, D.; Profeta, A.; Krikser, T.; Heinz, V. Adaption of the meat attachment scale (MEAS) to Germany: Interplay with food neophobia, preference for organic foods, social trust and trust in food technology innovations. Agric. Food Econ. 2023, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pânzaru, C.; Doliș, M.G.; Radu-Rusu, R.-M.; Pascal, C.; Maciuc, V.; Davidescu, M.-A. Equine Milk and Meat: Nutritious and Sustainable Alternatives for Global Food Security and Environmental Sustainability—A Review. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achmadi, E.R. Strategies managing smart packaging for food application. J. Food Agric. Prod. 2023, 3, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, A.; Dutta, J. Chitosan-based nanocomposite films and coatings: Emerging antimicrobial food packaging alternatives. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 97, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruippo, L.; Koivula, H.; Korhonen, J.; Toppinen, A.; Kylkilahti, E. Innovating for sustainability: Attributes, motivations, and responsibilities in the Finnish food packaging ecosystem. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2023, 3, 919–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safakas, K.; Lainioti, G.C.; Tsiamis, G.; Stathopoulou, P.; Ladavos, A. Utilizing essential oil components as natural antifungal preservatives in active bread packaging. Polymers 2025, 17, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulloni, V.; Marchi, G.; Gaiardo, A.; Valt, M.; Donelli, M.; Lorenzelli, L. Applications of Chipless RFID Humidity Sensors to Smart Packaging Solutions. Sensors 2024, 24, 2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Xu, B.; Gao, S.; Zhai, X.; Xu, F.; Shi, J. Innovative technologies reshaping meat industrialization: Challenges and opportunities in the intelligent era. Foods 2025, 14, 2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariah, M.A.A.; Vonnie, J.M.; Erna, K.H.; Nur’Aqilah, N.M.; Huda, N.; Wahab, R.A.; Rovina, K. The Emergence and Impact of Ethylene Scavengers Techniques in Delaying the Ripening of Fruits and Vegetables. Membranes 2022, 12, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, G.; Assadpour, E.; Zhang, W.; Jafari, S.M. Carbon nanomaterial-based sensors for smart food packaging. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 232, 121315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaani, M.; Cozzolino, C.A.; Castelli, G.; Farris, S. An overview of the intelligent packaging technologies in the food sector. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 51, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirpan, A.; Hidayat, S.H.; Djalal, M.; Ainani, A.F.; Yolanda, D.S.; Khosuma, M.; Solon, G.T.; Ismayanti, N. Trends over the last 25 years and future research into smart packaging for food: A review. Future Foods 2023, 8, 100252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, F.; Tagoe, J.N.A.; Di Maio, L. Development of PBS/nanocomposite PHB-based multilayer blown films with enhanced properties for food packaging applications. Materials 2024, 17, 2894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, N.S.; Lee, W.Y. Pectin-Based Active and Smart Film Packaging: A Comprehensive Review of Recent Advancements in Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, and Smart Colorimetric Systems for Enhanced Food Preservation. Molecules 2025, 30, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascall, M.A.; DeAngelo, K.; Richards, J.; Arensberg, M.B. Role and importance of functional food packaging in specialized products for vulnerable populations: Implications for innovation and policy development for sustainability. Foods 2022, 11, 3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshi, R.; Ezati, P.; Rhim, J.W. Recent advances in intelligent food packaging applications using natural food colorants. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 1, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.; Lall, A.; Kumar, S.; Patil, T.D.; Gaikwad, K.K. Plant-based edible films and coatings for food-packaging applications: Recent advances, applications, and trends. Sustain. Food Technol. 2024, 2, 1428–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, M.A.; Padmanabhan, S.C.; Cruz-Romero, M.C.; Cummins, E.; Kerry, J.P. Development of active, nanoparticle, antimicrobial technologies for muscle-based packaging applications. Meat Sci. 2017, 132, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Lloyd, K.; Birch, J.; Wu, X.; Mirosa, M.; Liao, X. A quantitative survey of consumer perceptions of smart food packaging in China. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 3977–3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.; Chang, B.P.; Hristov, H.; Pravst, I.; Profeta, A.; Millard, J. Changes in food consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic: Analysis of consumer survey data from the first lockdown period in Denmark, Germany, and Slovenia. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 635859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ton-That, P.; Dinh, T.A.; Gia-Thien, H.T.; Van Minh, N.; Nguyen, T.; Huynh, K.P.H. Novel packaging chitosan film decorated with green-synthesized nanosilver derived from dragon fruit stem. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 158, 110496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, R.; Sivakumar, S.; Kaur, H. Antimicrobial edible films in food packaging: Current scenario and recent nanotechnological advancements. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2021, 2, 100024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Zhang, M.; Chen, H.; Bhandari, B. Freshness monitoring technology of fish products in intelligent packaging. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 61, 1279–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zou, X.; Zhai, X.; Huang, X.; Jiang, C.; Holmes, M. Preparation of an intelligent pH film based on biodegradable polymers and roselle anthocyanins for monitoring pork freshness. Food Chem. 2019, 272, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyn, F.H.; Ismail-Fitry, M.R.; Noranizan, M.A.; Tan, T.B.; Hanani, Z.N. Recent advances in extruded polylactic acid-based composites for food packaging: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 266, 131340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, A.; Kaur, G.; Jain, H.; Singh, L. The role of smart packaging and consumer psychology in reducing food waste: A review. Food Humanit. 2025, 5, 100826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodero, A.; Escher, A.; Bertucci, S.; Castellano, M.; Lova, P. Intelligent packaging for real-time monitoring of food quality: Current and future developments. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Yan, X.; Cui, Y.; Han, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, R. An eco-friendly film of pH-responsive indicators for smart packaging. J. Food Eng. 2022, 321, 110943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindh, A.; Wijayarathna, E.K.B.; Ciftci, G.C.; Syed, S.; Bashir, T.; Kadi, N.; Zamani, A. Dry gel spinning of fungal hydrogels for the development of renewable yarns from food waste. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2024, 11, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arunan, I.; Crawford, R.H. Greenhouse gas emissions associated with food packaging for online food delivery services in Australia. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.P.; Prathapan, R.; Ng, K.W. Advances in biomaterials-based food packaging systems: Current status and the way forward. Biomater. Adv. 2024, 164, 213988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, F.; Andreescu, S. Nanotechnology-based approaches for food sensing and packaging applications. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 19309–19336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, Q.; Wu, H.; Zhou, Z.; Feng, S.; Deng, P.; Zou, H.; Tian, D.; Lu, C. Sustainable starch/lignin nanoparticle composite biofilms for food packaging applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, N.; Sharanagat, V.S.; Mor, R.S.; Kumar, K. Active and intelligent ethyladable packaging films using food and food waste-derived bioactive compounds: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 105, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koreshkov, M.; Takatsuna, Y.; Bismarck, A.; Fritz, I.; Reimhult, E.; Zirbs, R. Sustainable food packaging using modified kombucha-derived bacterial cellulose nanofillers in biodegradable polymers. RSC Sustain. 2024, 2, 2367–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Cao, L.; Wang, L.; Liu, S.; Zhang, M.; Li, C.; Waterhouse, G.I.N.; Fan, H.; Xu, J. Z-scheme heterojunction g-C3N4–TiO2 reinforced chitosan/poly(vinyl alcohol) film: Efficient and recyclable for fruit packaging. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 268, 131627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawal, U.; Kumar, N.; Samyuktha, R.; Gopi, A.; Robert, V.; Pugazhenthi, G.; Loganathan, S.; Valapa, R.B. Poly(lactic acid)/amine-grafted mesoporous silica-based composite for food packaging application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; Huang, X.; Li, Z.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, N.; Zhai, X.; Shi, J.; Zhang, J.; Shen, T.; Zhang, R.; et al. Application of smart packaging in fruit and vegetable preservation: A review. Foods 2025, 14, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanisamy, S.; Selvaraju, G.D.; Selvakesavan, R.K.; Venkatachalam, S.; Bharathi, D.; Lee, J. Unlocking sustainable solutions: Nanocellulose innovations for enhancing the shelf life of fruits and vegetables. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 261, 129592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavai, S.; Bains, A.; Sridhar, K.; Rashid, S.; Elossaily, G.M.; Ali, N.; Chawla, P.; Sharma, M. Formulation and application of poly lactic acid, gum, and cellulose-based ternary bioplastic for smart food packaging: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 268, 131687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Ngai, T. Recent advances in chemically modified cellulose and its derivatives for food packaging applications: A review. Polymers 2022, 14, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezati, P.; Rhim, J.W. pH-responsive pectin-based multifunctional films incorporated with curcumin and sulfur nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 230, 115638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İbrahim, Ş.E.N. Preparation and characterization of Leonardite and boric acid-added polylactic acid films for food packaging applications. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222, 119488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, A.; Kathuria, A.; Gaikwad, K.K. Metal–organic frameworks for active food packaging. A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022, 20, 1479–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Yang, D.; Chen, Y.; Shi, J.; Zhang, X.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J. MOF-Based Active Packaging Materials for Extending Post-Harvest Shelf-Life of Fruits and Vegetables. Materials 2023, 16, 3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Riahi, Z.; Hong, S.J.; Kim, J.Y.; Rhim, J.W.; Min, S.C. Cellulose nanofiber/gelatin-based multifunctional ethylene scavenging active packaging films integrated with TiO2-functionalized Bi (III) metal-organic frameworks. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2025, 51, 10159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.J.; Riahi, Z.; Khan, A.; Lee, J.G.; Kim, B.Y.; Min, S.C.; Shin, G.H.; Kim, J.T. Active packaging film utilizing cerium metal-organic frameworks doped with titanium dioxide as ethylene scavengers for postharvest ripening control of avocados. Food Chem. 2025, 489, 145025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imran, A.; Ahmed, F.; Ali, Y.A.; Naseer, M.S.; Sharma, K.; Bisht, I.S.; Alawadi, A.H.; Shehzadi, U.; Islam, F.; Shah, M.A. A comprehensive review on carbon dot synthesis and food applications. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 21, 101847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, W.; Feng, Y.; Shi, J. Carbon Dots as Multifunctional Nanofillers in Sustainable Food Packaging: A Comprehensive Review. Foods 2025, 14, 3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.H.H.; El-Ramady, H.; Prokisch, J. Food safety aspects of carbon dots: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2025, 23, 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshi, R.; Uzun, S.; Rhim, J.W. Edible coating using carbon quantum dots for fresh produce preservation: A review of safety perspectives. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 331, 103211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.K.; Itkor, P.; Lee, M.; Saenjaiban, A.; Lee, Y.S. Synergistic Integration of Carbon Quantum Dots in Biopolymer Matrices: An Overview of Current Advancements in Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Active Packaging. Molecules 2024, 29, 5138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, Z.; Khan, A.; Rhim, J.W.; Shin, G.H.; Kim, J.T. Red pepper waste-derived carbon dots incorporated sodium alginate/gelatin composite films for bioactive fruit preservation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 308, 142622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, Z.; Khan, A.; Ebrahimi, M.; Rhim, J.W.; Shin, G.H.; Kim, J.T. Exploring Sustainable Carbon Dots as UV-Blocking Agents for Food Preservation. Compr. Rev. Food. Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, M.B.; Marjani, A.P.; Balkanloo, P.G. Introducing graphene quantum dots in decomposable wheat starch-gelatin based nano-biofilms. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhou, X.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, X.; Zhu, J.; Cheng, W. Multifunctional Metal–Organic Frameworks for Enhancing Food Safety and Quality: A Comprehensive Review. Foods 2025, 14, 4111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, J.; Yang, L.; Dong, X.; Sun, Y.P. Antimicrobial properties of carbon “quantum” dots for food safety applications. J. Nanopart. Res. 2025, 27, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, M.; Domaradzki, P.; Skałecki, P.; Kaliniak-Dziura, A.; Stanek, P.; Teter, A.; Grenda, T.; Florek, M. Use of sustainable packaging materials for fresh beef vacuum packaging application and product assessment using physicochemical means. Meat Sci. 2024, 216, 109551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yetgin, S.; Ağırsaygın, M.; Yazgan, İ. Smart Food Packaging Films Based on a Poly(lactic acid), Nanomaterials, and a pH Sensitive Dye. Processes 2025, 13, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, V.; Gaur, P.; Rustagi, S. Sensors, society, and sustainability. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2024, 40, e00952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Yu, Z.; Dong, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, C.; Ye, C. Application of visual intelligent labels in the assessment of meat freshness. Food Chem. 2024, 460, 140562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukder, S.; Mendiratta, S.K.; Kumar, R.R.; Agrawal, R.K.; Soni, A.; Luke, A.; Chand, S. Jamun fruit (Syzgium cumini) skin extract–based indicator for monitoring chicken patties quality during storage. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahab, S.N.; Othman, N.; Sayuti, N.M.; Mohaini, M.L.; Atan, R. Assessing the growth and trends of smart packaging: A case of food distribution. J. Inf. Technol. Manag. 2025, 17, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalpana, S.; Priyadarshini, S.R.; Leena, M.M.; Moses, J.A.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. Intelligent packaging: Trends and applications in food systems. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 93, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, V.; Kandeepan, G.; Vishnuraj, M.R.; Soni, A. Anthocyanins-based indicator sensor for intelligent packaging application. Agric. Res. 2016, 5, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirupathi Vasuki, M.; Kadirvel, V.; Pejavara Narayana, G. Smart packaging—An overview of concepts and applications in various food industries. Food Bioeng. 2023, 2, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabadurmus, O.; Kayikci, Y.; Demir, S.; Koc, B. A data-driven decision support system with smart packaging in grocery store supply chains during outbreaks. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2023, 85, 101417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoica, M.; Bichescu, C.I.; Crețu, C.-M.; Dragomir, M.; Ivan, A.S.; Podaru, G.M.; Stoica, D.; Stuparu-Crețu, M. Review of Bio-Based Biodegradable Polymers: Smart Solutions for Sustainable Food Packaging. Foods 2024, 13, 3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escursell, S.; Llorach-Massana, P.; Roncero, M.B. Sustainability in e-commerce packaging: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethunga, M.; Gunathilake, K.D.P.P.; Ranaweera, K.K.D.S.; Munaweera, I. Antimicrobial and antioxidative electrospun cellulose acetate–essential oil nanofibrous membranes for active food packaging. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2024, 97, 103802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.R.; Hsieh, S.; Ricacho, N. Innovative food packaging, food quality and safety, and consumer perspectives. Processes 2022, 10, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masamba, M. Impact of Food Packaging Materials on the Shelf-Life and Quality of Packaged Food Products. Int. J. Food Sci. 2024, 5, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W.; Haque, A.; Mohibbullah, M.; Khan, S.I.; Islam, M.A.; Mondal, H.T.; Ahmmed, R. A review on active packaging for quality and safety of foods: Current trends, applications, prospects and challenges. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2022, 33, 100913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkhari, T.; Adeyemi, J.O.; Fawole, O.A. Recent Advances in the Fabrication of Intelligent Packaging for Food Preservation: A Review. Processes 2025, 13, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, V.; Singh, S.; Das, D. Environmental Impact Assessment of Active Biocomposite Packaging and Comparison with Conventional Packaging for Food Application. In Proceedings of the DS 130: Proceedings of NordDesign 2024, Reykjavik, Iceland, 12–14 August 2024; pp. 402–410. [Google Scholar]

- Bala, A.; Laso, J.; Abejón, R.; Margallo, M.; Fullana-i-Palmer, P.; Aldaco, R. Environmental assessment of the food packaging waste management system in Spain: Understanding the present to improve the future. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 702, 134603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfelli, F.; Roguszewska, M.; Torta, G.; Iurlo, M.; Cespi, D.; Ciacci, L.; Passarini, F. Environmental impacts of food packaging: Is it all a matter of raw materials? Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2024, 49, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.C.; Su, M.Y.; Yuan, X.Y.; Lv, H.Q.; Feng, R.; Wu, L.J.; Gao, X.P.; An, Y.X.; Li, Z.W.; Li, M.Y.; et al. Green fabrication of modified lignin/zeolite/chitosan-based composite membranes for preservation of perishable foods. Food Chem. 2024, 460, 140713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.I.; Lee, S.J.; Chathuranga, K.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, M.H.; Park, W.H. Multifunctional and edible egg white/amylose–tannin bilayer film for perishable fruit preservation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 274, 133207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ying, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Ge, Y.; Yuan, C.; Wu, C.; Hu, Y. A pH-indicating intelligent packaging composed of chitosan–purple potato extractions strengthened by surface-deacetylated chitin nanofibers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 127, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Ponciano, C.; Gonzaga, F.C.; de Oliveira, C.P. Smart packaging based on chitosan acting as indicators of changes in food: A technological prospecting review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 145722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, C.V.L.; Jayatilake, S.; Rajapakse, H.U.K.D.Z.; Gunarathne, H.M.N.R.; Wanigasinghe, H.G. Consumer perceptions of smart packaging technologies for food. In Intelligent Packaging; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukid, F. Smart food packaging: An umbrella review of scientific publications. Coatings 2022, 12, 1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, A.R.; Boumans, H.; Slaghek, T.; Van Veen, J.; Rijk, R.; Van Zandvoort, M. Active and intelligent packaging for food: Is it the future? Food Addit. Contam. 2005, 22, 975–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, P.; Kochhar, A. Active packaging in food industry: A review. J. Environ. Sci. Toxicol. Food Technol. 2014, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M.A.; Barbosa, C.H.; Ribero-Santos, R.; Tomé, S.; Fernando, A.L.; Silva, A.S.; Vilarinho, F. Emerging Trends in Active Packaging for Food: A Six-Year Review. Foods 2025, 14, 2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohail, M.; Sun, D.W.; Zhu, Z. Recent developments in intelligent packaging for enhancing food quality and safety. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 2650–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutta, M.N.M.; Ahmad, M. Secure identification, traceability and real-time tracking of agricultural food supply during transportation using internet of things. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 65660–65675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stramarkou, M.; Boukouvalas, C.; Fragkouli, D.N.; Tsamis, C.; Krokida, M. Evaluating the Sustainability of Tetra Pak Smart Packaging Through Life Cycle and Economic Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepika, L.K.; Gaikwad, K.K. Carbon dots for food packaging applications. Sustain. Food Technol. 2023, 1, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, M.; Akdaşçi, E.; Eker, F.; Bechelany, M.; Karav, S. Recent Advances of Silver Nanoparticles in Wound Healing: Evaluation of In Vivo and In Vitro Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Liu, Q.; Liu, M.; Chen, X.; Lin, H.; Zheng, Z.; Zhu, J.; Dai, C.; Dong, X.; Yang, D.P. Carbon dots enhanced gelatin/chitosan bio-nanocomposite packaging film for perishable foods. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 4577–4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, Z.; Hong, S.J.; Rhim, J.W.; Shin, G.H.; Kim, J.T. High-performance multifunctional gelatin-based films engineered with metal-organic frameworks for active food packaging applications. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 144, 108984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.F. Design of Polymeric Films for Antioxidant Active Food Packaging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, S.; Amaro-Gahete, J.; Espinosa, E.; Benítez, A.; Romero-Salguero, F.J.; Rodríguez, A. Engineering PVA-CNF-MOF Composite Films for Active Packaging: Enhancing Mechanical Strength, Barrier Performance, and Stability for Fresh Produce Preservation. Molecules 2025, 30, 3971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthu, A.; Nguyen, D.H.H.; Neji, C.; Törős, G.; Ferroudj, A.; Atieh, R.; Prokisch, J.; El-Ramady, H.; Béni, Á. Nanomaterials for Smart and Sustainable Food Packaging: Nano-Sensing Mechanisms, and Regulatory Perspectives. Foods 2025, 14, 2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayak, A.; Dutta, D. A comprehensive review on CRISPR and artificial intelligence based emerging food packaging technology to ensure “safe food”. Sustain. Food Technol. 2023, 1, 641–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, C.M. The food systems in the era of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic crisis. Foods 2020, 9, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidescu, M.-A.; Pânzaru, C.; Mădescu, B.-M.; Radu-Rusu, R.-M.; Doliș, M.G.; Simeanu, C.; Usturoi, A.; Ciobanu, A.; Creangă, Ș. Genetic Diversity and Phylogenetic Analysis of the Endangered Transylvanian Pinzgau Cattle: A Key Resource for Biodiversity Conservation and the Sustainability of Livestock Production. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, B. Green packaging materials design and efficient packaging with Internet of Things. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 58, 103186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Gahlawat, V.K.; Rahul, K.; Mor, R.S.; Malik, M. Sustainable innovations in the food industry through artificial intelligence and big data analytics. Logistics 2021, 5, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnama, S.; Sejati, W. Internet of things, big data, and artificial intelligence in the food and agriculture sector. Int. J. Artif. Intell. 2023, 1, 156–174. Available online: https://scispace.com/pdf/internet-of-things-big-data-and-artificial-intelligence-in-2yjsedab.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Paliwoda, B.; Górna, J.; Biegańska, M.; Wójcicki, K. Application of industrial internet of things (IIoT) in the packaging industry in Poland. LogForum 2023, 19, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlZubi, A.A.; Galyna, K. Artificial intelligence and internet of things for sustainable farming and smart agriculture. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 78686–78692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stramarkou, M.; Boukouvalas, C.; Koskinakis, S.E.; Serifi, O.; Bekiris, V.; Tsamis, C.; Krokida, M. Life Cycle Assessment and Preliminary Cost Evaluation of a Smart Packaging System. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, A.; Tayel, A. Food 2050 Concept: Trends That Shape the Future of Food. J. Future Food 2025. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2772566925001260 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Panou, A.; Lazaridis, D.G.; Karabagias, I.K. Application of Smart Packaging on the Preservation of Different Types of Perishable Fruits. Foods 2025, 14, 1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| (a). Meat and Meat Products | ||

| Application Focus | Reported and Quantified Outcome | References |

| Absorbent pads with lemongrass essential oil integration | Enhanced inhibition zones against S. aureus and E. coli compared to control samples | [49,50,51] |

| Blockchain -based supply chain records linked with intelligent labels | Improved transparency and consumer trust through farm-to-retail traceability data access | [52,53] |

| Natural antimicrobial active films | Met consumer preference for additive-free preservation while aligning with sustainability targets | [53] |

| Absorbent pad + lemongrass essential oil under MAP conditions | 1–1.5 log CFU/g reduction viable count over 12 days of chilled storage compared to control packs; maintained acceptable color scores | [49,54] |

| Silver-zeolite LDPE film wrap for fresh beef cuts | Inhibited mesophilic bacteria growth by 2–3 log CFU/g over 14 days at 4 °C while sustaining lipid oxidation below threshold PVs | [55,56] |

| PHMB-loaded nanofiber mats placed inside overwrap trays for pork slices | Reduced aerobic plate count growth rate constant by 35% relative to controls; no degradation of drip loss performance parameters | [57] |

| Volatile amine-sensitive freshness indicator label integrated into high- MAP beef steaks | Provided visual alert (>90% correct positive signals) prior to reaching the sensory rejection thresholds determined by trained panelists | [58,59] |

| RFID-linked gas-sensing MAP containers for export lamb shipments (>20 days transit) | Continuous / logging identified micro-leakage events allowing corrective action before sensory deterioration; reduced shipment rejections by 15% year-on-year | [60] |

| (b). Milk and dairy products | ||

| Application focus | Reported and quantified outcome | References |

| Embedded biosensors detecting lactic acid accumulation | Early warning system for microbial growth enabling timely removal from distribution channels | [58,61] |

| Intelligent indicators monitoring temperature fluctuations during transport/storage | Provided verifiable cold-chain compliance data to retailers and consumers | [55,62] |

| Bio-nanocomposite films improving barrier properties against oxygen ingress | Reduced oxidation-related flavor deterioration over longer storage periods | [58] |

| Chitosan –PLA composite film wrap for soft cheese | Suppressed surface bacterial counts by >2 log CFU/cm2 over 10-day storage at 4 °C; no effect on pH or ripening profile | [63] |

| O 2 scavenging bottle closures for UHT milk | Reduced headspace oxygen from 1.8% to 0.05% within three days; prevented oxidative off-flavors up to end-of-shelf-life testing point at 120 days ambient storage | [64] |

| Lactic acid biosensor integrated into biodegradable multilayer carton liners | Provided early spoilage alert 48 h before sensory detection threshold; maintained full compostability under industrial conditions post-use | [58,65] |

| TTI label on HDPE fresh milk bottles in urban chilled distribution trials | Correctly identified 95% of cold-chain breaks exceeding 2 h at >8 °C during monitored delivery routes over two months study period | [66] |

| RFID-linked TTI arrays in export butter shipments (30 days) logging continuous temperature profiles accessible via blockchain nodes at import inspection points | Enabled rejection avoidance by re-validating compliance in cases where container sensor logs contested portside infractions claims; reduced unjustified discard incidents by 12% year-on-year | [67] |

| (c). Bakery products | ||

| Application focus | Reported and quantified outcome | References |

| PLA –protein composite film with clove oil for sliced bread packaging | Reduced visible mold incidence by 80% over 10-day ambient storage; no adverse sensory defect noted | [68] |

| Starch-based laminate incorporating anhydrous calcium chloride layer for cookies transport in humid climates | Maintained below 0.50 during 30-day test cycle; prevented loss of crispness relative to unprotected controls | [67,69] |

| Rosemary-extract infused LDPE pouches for butter-rich biscuits | Delayed peroxide value (PV) increase beyond sensory detection threshold by 40% over 60 days storage at 25 °C | [55,70] |

| Humidity-sensitive printed ink patch inside bread bag headspace area indicating unsafe high-moisture condition via irreversible color change | Correctly forecast mold outbreak risk 24–48 h before visual mycelium appearance on loaf crusts under simulated distribution conditions | [58,71] |

| Compostable cellulose-acetate cupcake liners impregnated with cinnamon oil vapors release system | Extended microbial-free shelf life by 3 days under bakery store display settings while enabling post-use biodegradation within 90 days under industrial composting conditions | [69] |

| (d) Vegetables and Fruits | ||

| Application focus | Reported and quantified outcome | References |

| Activated carbon -clay composite film for bananas during shipping | Extended green stage by 9 days relative to plain PE wrap; maintained firmness within quality threshold for retail display acceptance rates above 85% after arrival | [72] |

| Cellulose fiber-based humidity absorber pads for packaged lettuce leaves | Reduced mass loss from turgor decline by 22% over 7-day storage; microbial counts remained below spoilage limit throughout trial period | [53,69] |

| Graphene oxide VOC sensor arrays integrated into strawberry export clamshells | Achieved 90% predictive accuracy for mold development within 48 h of first detectable colony growth under partial refrigeration transport regimes | [55,73] |

| PLA –chitosan biodegradable films with essential oil microcapsules for cherry tomatoes | Suppressed visible spoilage incidence by 40% after 14 days ambient storage compared with non-active PLA controls; maintained average lycopene content retention above 95% baseline level measured at harvest day | [74] |

| Multi-layer sachet system combining potassium permanganate granules and silica-gel desiccant for mixed-fruit cartons during intercontinental sea freight (>21 days) | Reduced ethylene concentration inside carton headspace from initial 0.45 ppm to below 0.10 ppm throughout transit; prevented cross-ripening chain reaction among mixed climacteric loads leading to rejection rate drop from 12% to under 5% year-on-year shipment statistics | [55,75] |

| (a). Meat and Meat Products | ||

| Type | Description | References |

| Passive | High-barrier multilayer films prevent oxygen/moisture ingress; vacuum-sealed PE or PP formats for chilled transport | [76] |

| Active | Antimicrobial films with essential oils or silver-zeolites; oxygen scavengers integrated into modified atmosphere packaging (MAP) units | [55,77] |

| Intelligent | Volatile amine detectors: pH-sensitive indicators signaling microbial activity before sensory spoilage markers arise | [58,78] |

| Hybrid Smart Systems | MAP with embedded gas sensors transmitting data via RFID for continuous cold chain surveillance | [69] |

| (b). Milk and dairy products | ||

| Type | Description | References |

| Passive | High-barrier cartons or multilayer bottles minimizing light and oxygen ingress; PET with UV-blocking additives for milk | [79,80] |

| Active | Antimicrobial films/coatings (e.g., chitosan-based) inhibiting psychrotrophs; oxygen scavenging closures for cheese ripening control | [55,81] |

| Intelligent | TTIs signaling cumulative chill-chain breaks; biosensors detecting pH or lactic acid change indicating microbial growth | [66] |

| Hybrid Smart Systems | RFID-enabled TTIs logging temperature history linked with blockchain for cold chain audits in export milk consignments | [69,82] |

| (c). Bakery products | ||

| Type | Description | References |

| Passive | High-barrier laminates preventing moisture ingress; metallized films blocking light-induced oxidation in chocolate coatings | [69] |

| Active | Moisture absorbers embedded in bread bags; antifungal essential oil-infused biopolymer film wraps | [55,83] |

| Intelligent | Humidity-sensitive inks alerting excessive water vapor for mold-risk scoring; integrity seals showing tamper detection | [58,84] |

| Hybrid Smart Systems | Bio-based films combining humidity absorption with visual indicator windows color-coded for safe/unsafe conditions | [79,85] |

| (d). Vegetables and Fruits | ||

| Type | Description | References |

| Passive | Gas-permeable films allowing controlled respiration while limiting water vapor transmission; UV-blocking wraps to prevent photodegradation of pigments | [69] |

| Active | Ethylene scavenger sachets; humidity absorber pads preventing fungal proliferation in high-moisture items | [55,86] |

| Intelligent | VOC-sensitive nanosensors for senescence detection; TTI labels recording temperature deviations during long-haul shipping | [58,87] |

| Hybrid Smart Systems | Biodegradable films incorporating both ethylene absorption agents and real-time freshness indicator windows visible to handlers/consumers | [87] |

| Packaging System Type | Key Characteristics/Typical Performance | Relevance as a Benchmark for Smart Packaging | Indicative Cost and Scalability Considerations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional passive packaging (plastics, paper, glass, metal) | Provides basic barriers and protection; no active or sensing functions | Serves as the traditional baseline for evaluating the added value of active/smart systems | Generally low cost due to mass production and established industrial supply chains; highly scalable | [7,10,17,152] |

| Active packaging systems | Includes antimicrobial/antioxidant agents; oxygen/moisture scavengers | Benchmark for functional improvement over passive packaging | Moderate material and incorporation cost depending on active agents; scalable but sometimes limited by regulatory approval of active substances | [10,16,17,150] |

| Intelligent monitoring packaging (indicators, sensors, RFID, TTIs) | Provides real-time information on product quality or temperature history | Benchmark for evaluating intelligence and monitoring capability | Higher cost due to sensing elements, electronics or smart indicators; scalability depends on target food category and cost–benefit ratio | [17,149,150] |

| Nano-enabled active and intelligent packaging (nanocomposites, nano-coatings, nano-sensors) | Enhanced barrier, antimicrobial/antioxidant functionality, possible sensing capabilities; often multifunctional | Represents an advanced benchmark for high-performance smart packaging | Costs depend on nanomaterial type, synthesis method, loading level, and regulatory requirements; industrial scale-up feasible but still under development for certain nano-platforms | [10,17,149,152] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Davidescu, M.A.; Pânzaru, C.; Mădescu, B.M.; Poroșnicu, I.; Simeanu, C.; Usturoi, A.; Matei, M.; Doliș, M.G. Advances and Challenges in Smart Packaging Technologies for the Food Industry: Trends, Applications, and Sustainability Considerations. Foods 2025, 14, 4347. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244347

Davidescu MA, Pânzaru C, Mădescu BM, Poroșnicu I, Simeanu C, Usturoi A, Matei M, Doliș MG. Advances and Challenges in Smart Packaging Technologies for the Food Industry: Trends, Applications, and Sustainability Considerations. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4347. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244347

Chicago/Turabian StyleDavidescu, Mădălina Alexandra, Claudia Pânzaru, Bianca Maria Mădescu, Ioana Poroșnicu, Cristina Simeanu, Alexandru Usturoi, Mădălina Matei, and Marius Gheorghe Doliș. 2025. "Advances and Challenges in Smart Packaging Technologies for the Food Industry: Trends, Applications, and Sustainability Considerations" Foods 14, no. 24: 4347. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244347

APA StyleDavidescu, M. A., Pânzaru, C., Mădescu, B. M., Poroșnicu, I., Simeanu, C., Usturoi, A., Matei, M., & Doliș, M. G. (2025). Advances and Challenges in Smart Packaging Technologies for the Food Industry: Trends, Applications, and Sustainability Considerations. Foods, 14(24), 4347. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244347