Bridging Tradition and Innovation: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis of Turkish Fermented Foods

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Traditional Fermented Foods in Türkiye

3. Cultural, Nutritional, and Economic Importance of Traditional Fermented Foods

- Yogurt, kefir, and ayran are rich sources of calcium, protein, and lactic acid bacteria, which probably promote gut microbiota balance and immune modulation;

- Sourdough breads and tarhana reduce phytates, thereby improving the absorption of minerals and overall protein digestibility;

- Fermented vegetables and pickles contain fiber, antioxidants, and vitamins such as C and K, supporting metabolic and cardiovascular health.

| Fermented Food | Geographical Indication | City | Registration Numbers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tarhana | Cide Tarhanası | Kastamonu | 1380 |

| Kızılcık Tarhanası (Cornelian Cherry Tarhana) | Bolu- Kütahya | 252 | |

| Sıkma Tarhana | Amasya | 1300 | |

| Fethiye Tarhanası | Muğla | 1484 | |

| Şirin Tarhanası | Gaziantep | 1078 | |

| Gediz Tarhanası | Kütahya | 1108 | |

| Malatya Tarhanası | Malatya | 1174 | |

| Maraş Tarhanası | Kahramanmaraş | 154 | |

| Göce Tarhanası | Muğla | 458 | |

| Üzüm Tarhanası (Grape Tarhana) | Tokat | 1612 | |

| Uşak Tarhanası | Uşak | 209 | |

| Ayran | Susurluk Ayranı | Balıkesir | 238 |

| Vinegar | Sirkencübin | Konya | G7 |

| Boza | Velimeşe Bozası | Tekirdağ | 721 |

| Shalgam | Adana Şalgamı | Adana | 489 |

| Tarsus Şalgamı | Mersin | 84 | |

| Hardaliye | Kırklareli Hardaliyesi | Kırklareli | 278 |

| Olive | Akhisar Uslu Zeytini | Manisa | 165 |

| Akhisar Domat Zeytini | Manisa | 166 | |

| Yamalak Sarısı Zeytini | Aydın | 732 | |

| Memecik Zeytini | Aydın | 749 | |

| Edremit Körfezi Yeşil Çizik Zeytini | Balıkesir | 189 | |

| Edincik Zeytini | Balıkesir | 1556 | |

| Büyükbelen Tekir Zeytini | Manisa | 1611 | |

| Gemlik Zeytini | Bursa | 76 | |

| Halhalı Zeytini | Hatay | 1353 | |

| Karamürsel Samanlı Zeytini | Kocaeli | 1622 | |

| Milas Ekşili Zeytini | Muğla | 1691 | |

| Milas Yağlı Zeytini | Muğla | 446 | |

| Milas Çekişke Zeytini | Muğla | 1109 | |

| Tarsus Sarıulak Zeytini | Mersin | 345 | |

| Pickle | Acur-Biber Turşusu | Gaziantep | 1057 |

| Midyat Turşusu/Midyat Acur Turşusu | Mardin | 1131 | |

| Çorti Turşusu | Muş | 294 | |

| Orhangazi Gedelek Turşusu | Bursa | 249 | |

| Taflan Turşusu | Ordu | 1102 | |

| Yayla Pancarı Turşusu | Ordu | 269 | |

| Kapari Turşusu | Osmancık | 1636 | |

| Reşadiye Kırmızı Pezik Turşusu | Tokat | 1455 | |

| Pezik Turşusu | Sivas | 492 | |

| İskilip Turşusu | Çorum | 131 | |

| Çubuk Turşusu | Ankara | 99 | |

| Sucuk | Bez Sucuk | Tokat | 990 |

| Gilaburu | Akkışla Gilaburusu | Kayseri | 669 |

| Bünyan Gilaburusu | Kayseri | 389 | |

| Gemerek Gilaburusu | Sivas | 241 | |

| Cheese | Carra Peyniri | Hatay | 679 |

| Sıkma Peyniri | Gaziantep | 356 | |

| Atlantı Dededağ Tulum Peyniri | Konya | 1327 | |

| Ayvalık Kelle Peyniri | Balıkesir | 1664 | |

| Tulum Peyniri | Ağrı | 1565 | |

| Bergama Tulum Peyniri | İzmir | 1597 | |

| Örgü Peyniri | Diyarbakır | 170 | |

| Beyaz Peyniri | Edirne | 93 | |

| Elbistan Kelle Peyniri | Kahramanmaraş | 1500 | |

| Tulum Peyniri | Erzincan | 30 | |

| Civil Peyniri | Erzurum | 116 | |

| Küflü Civil Peyniri | Erzurum | 164 | |

| Ezine Peyniri | Çanakkale | 86 | |

| Deleme Peyniri | Gümüşhane | 694 | |

| Hanak Tel Peyniri | Ardahan | 1563 | |

| Divle Obruğu Tulum Peyniri | Karaman | 270 | |

| Kargı Tulum Peyniri | Çorum | 933 | |

| Gravyer Peyniri | Kars | 1640 | |

| Kepsut Bükdere Küflü Katık Peyniri | Balıkesir | 1683 | |

| Eski Kaşar Peyniri | Kırklareli | 1408 | |

| Beyaz Peyniri | Kırklareli | 636 | |

| Manyas Kelle Peynir | Balıkesir | 628 | |

| Malatya Peyniri | Malatya | 1164 | |

| Malkara Eski Kaşar Peyniri | Tekirdağ | 261 | |

| Maraş Parmak/Sıkma Peynir | Kahramanmaraş | 727 | |

| Mengen Peyniri | Bolu | 1482 | |

| Pınarbaşı Uzunyayla Çerkes Peyniri | Kayseri | 724 | |

| Sakarya Abhaz (Abaza) Peyniri | Sakarya | 746 | |

| Savaştepe Mihaliç Kelle Peyniri | Balıkesir | 1405 | |

| Talas Çörek(Çömlek Peyniri | Kayseri | 1560 | |

| Urfa Peyniri/Şanlıurfa Peyniri | Urfa | 807 | |

| Vakfıkebir Külek Peyniri | Trabzon | 764 | |

| Van Otlu (Herby) Peyniri | Van | 405 | |

| Yozgat Çanak Peyniri | Yozgat | 281 | |

| Çankırı Küpecik Peyniri | Çankırı | 907 | |

| Çayeli Koloti Peyniri | Rize | 1199 | |

| İvrindi Kelle Peynir | Balıkesir | 1025 | |

| İzmir Tulum Peyniri | İzmir | 1006 | |

| Pastırma | Afyon Pastırması | Afyon | 73 |

| Ankara Erkeç Pastırması | Ankara | 408 | |

| Erzurum Pastırması | Erzurum | 1311 | |

| Kastamonu Pastırması | Kastamonu | 711 | |

| Kayseri Pastırması | Kayseri | 36 | |

| Sivas Pastırması | Sivas | 1129 | |

| Sourdough | Afyonkarahisar Ak Pide | Afyon | 1265 |

| Mamak Kutludüğün Ekşi Maya Ekmeği | Ankara | 827 | |

| Kürtün Araköy Ekmeği | Gümüşhane | 449 | |

| Kalecik Ekmeği | Ankara | 559 | |

| Gümüşhane Ekmeği | Gümüşhane | 221 | |

| Tokat Ekmeği | Tokat | 896 | |

| Vakfıkebir Ekmeği | Trabzon | 372 | |

| Çavuşlu Ekmeği | Giresun | 623 | |

| Bolu Patates Ekmeği Bolu | Bolu | 544 | |

| Çöven Ekmeği | Bartın | 1045 | |

| Afyonkarahisar Patates Ekmeğ | Afyon | 371 | |

| Alaşehir Ekmeği | Manisa | 1119 | |

| Cihanbeyli Gömeç Ekmeği | Konya | 1241 | |

| Gelveri Ekmeği | Aksaray | 1040 | |

| Malatya Ekmeği | Malatya | 1127 | |

| Erzurum Hasankale Lavaşı | Erzurum | 1020 | |

| Erzurum Acem Ekmeği | Erzurum | 1365 |

4. Bibliometric Analysis

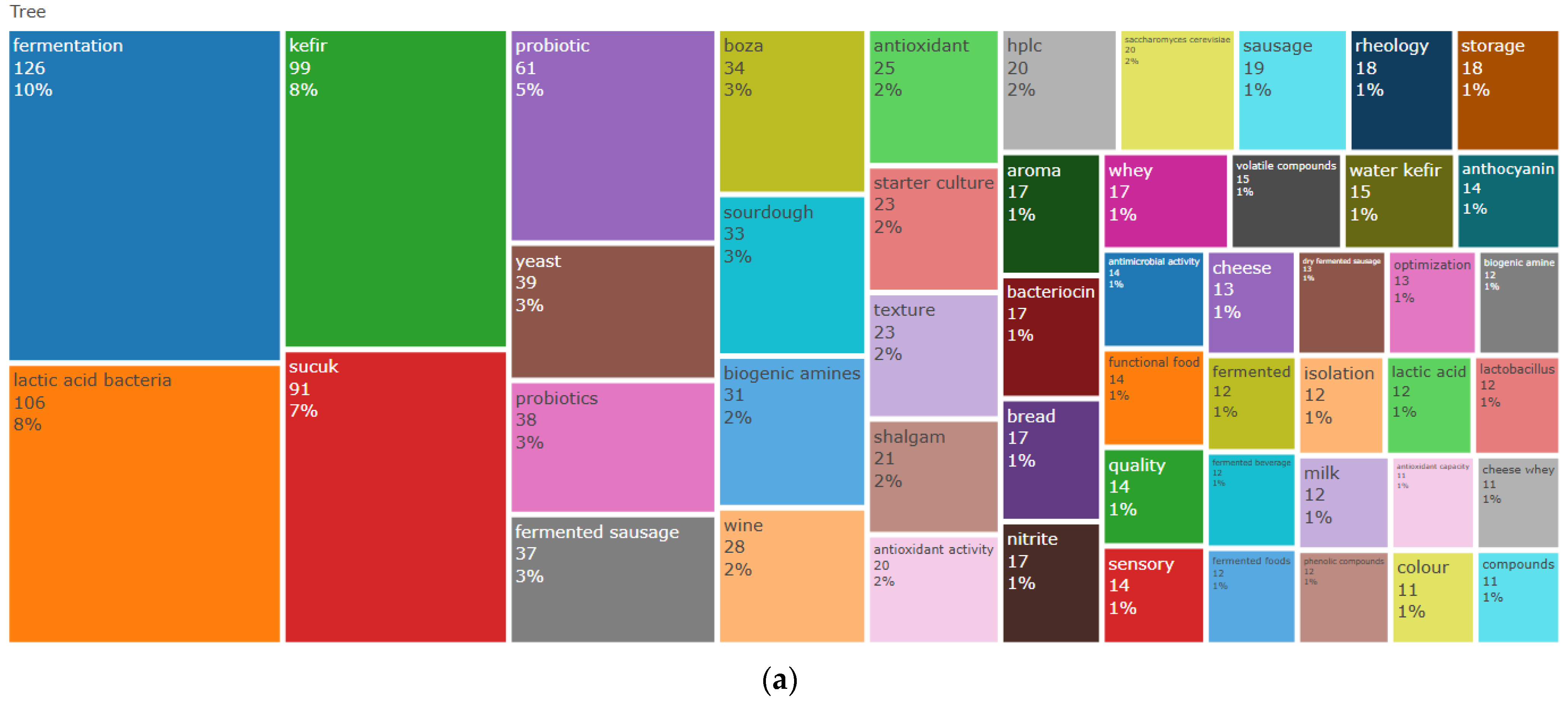

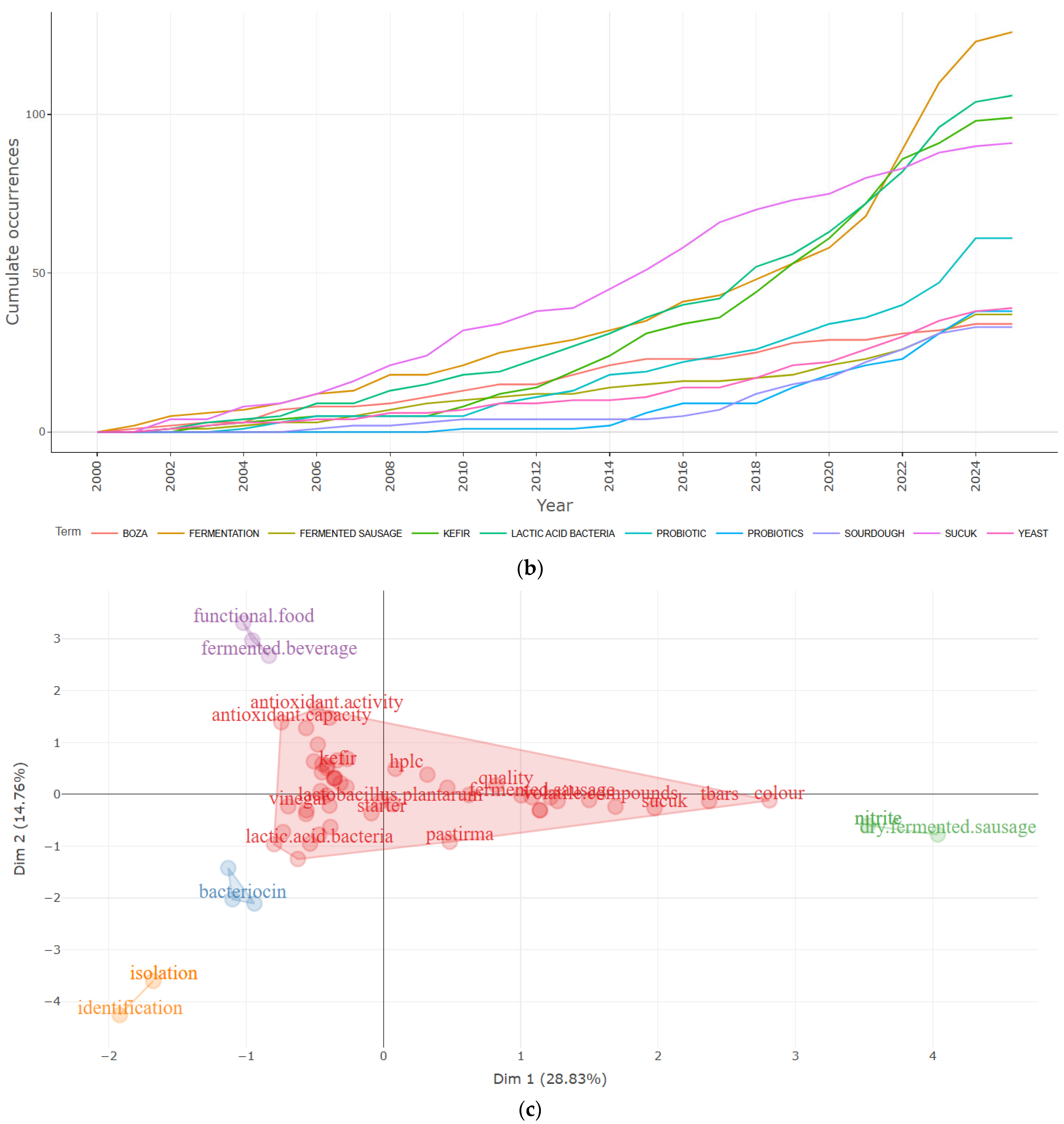

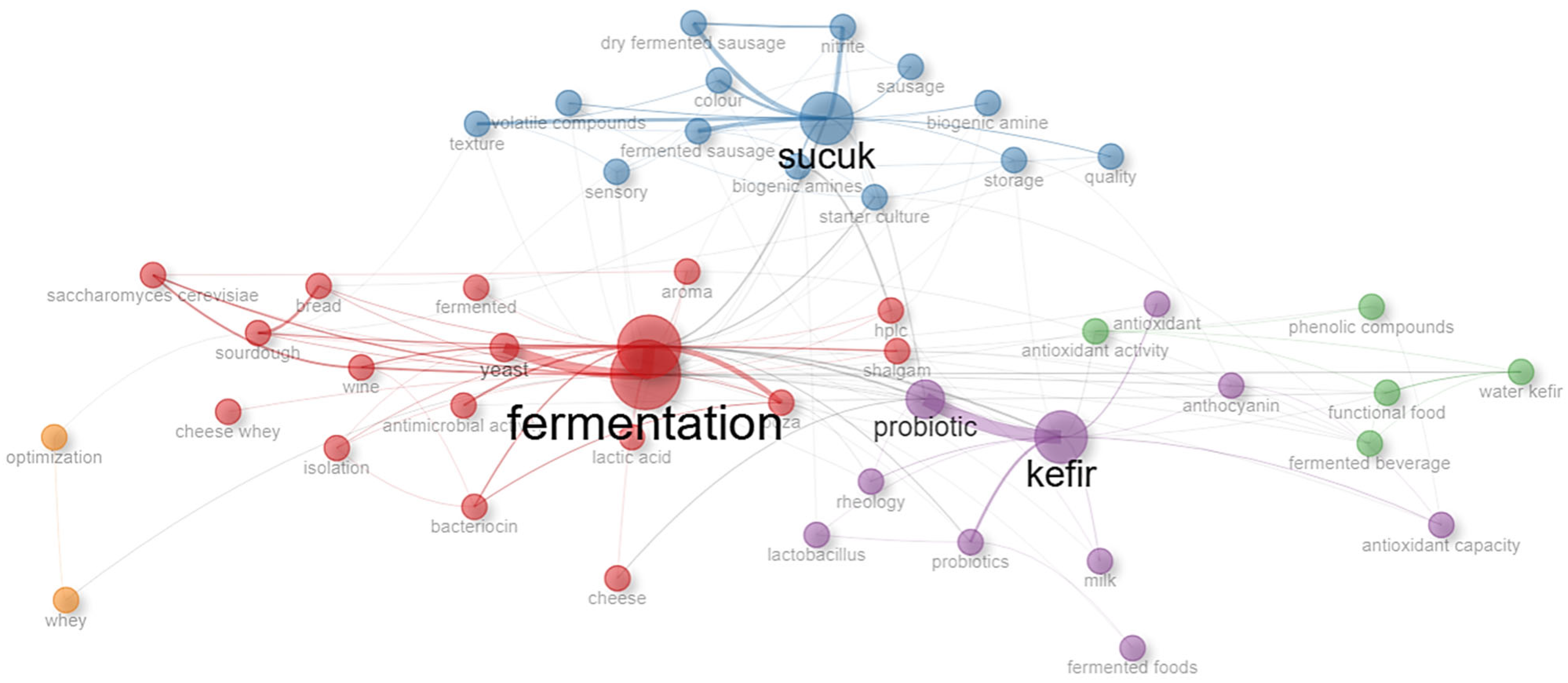

4.1. Author’s Keywords and Research Connections

4.2. Thematic Map and Trend Topics

4.3. International Collaborations on Turkish Fermented Foods

5. Future Perspectives

5.1. The Role of Omics Technologies in Turkish Fermented Products Research

5.2. Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Fermented Foods

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Montet, D.; Ray, R.C.; Zakhia-Rozis, N. Lactic Acid Fermentation of Vegetables and Fruits. In Microorganisms and Fermentation of Traditional Foods; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; pp. 108–140. ISBN 9780429157165. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, R.C.; Joshi, V.K. Fermented Foods: Past, Present and Future. In Microorganisms and Fermentation of Traditional Foods; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; pp. 1–36. ISBN 9781482223095. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrocino, I.; Rantsiou, K.; McClure, R.; Kostic, T.; de Souza, R.S.C.; Lange, L.; FitzGerald, J.; Kriaa, A.; Cotter, P.; Maguin, E.; et al. The Need for an Integrated Multi-OMICs Approach in Microbiome Science in the Food System. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2023, 22, 1082–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, D.; Yang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Wan, W.; Liu, W.; Xiong, X. Metagenomic Insights into Nitrogen-Cycling Microbial Communities and Their Relationships with Nitrogen Removal Potential in the Yangtze River. Water Res. 2024, 265, 122229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, M.; Rakotondrabe, T.F.; Chen, G.; Guo, M. Advances in Microbial Analysis: Based on Volatile Organic Compounds of Microorganisms in Food. Food Chem. 2023, 418, 135950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourrie, B.C.T.; Cotter, P.D.; Willing, B.P. Traditional Kefir Reduces Weight Gain and Improves Plasma and Liver Lipid Profiles More Successfully than a Commercial Equivalent in a Mouse Model of Obesity. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 46, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, A.M.; Crispie, F.; Kilcawley, K.; O’Sullivan, O.; O’Sullivan, M.G.; Claesson, M.J.; Cotter, P.D. Microbial Succession and Flavor Production in the Fermented Dairy Beverage Kefir. mSystems 2016, 1, e00052-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marco, M.L.; Sanders, M.E.; Gänzle, M.; Arrieta, M.C.; Cotter, P.D.; De Vuyst, L.; Hill, C.; Holzapfel, W.; Lebeer, S.; Merenstein, D.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) Consensus Statement on Fermented Foods. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaundal, R.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, S.; Singh, D.; Kumar, D. Polyphenolic Profiling, Antioxidant, and Antimicrobial Activities Revealed the Quality and Adaptive Behavior of Viola Species, a Dietary Spice in the Himalayas. Molecules 2022, 27, 3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanlibaba, P.; Tezel, B.U. Traditional Fermented Foods in Anatolia. Acta Sci. Pol.-Technol. Aliment. 2023, 22, 193–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, R.; Temiz, A.; Açık, L.; Keskin, A.Ç. Genetic Differentiation of Lactobacillus Delbrueckii Subsp. Bulgaricus and Streptococcus Thermophilus Strains Isolated from Raw Milk Samples Collected from Different Regions of Turkey. Food Biotechnol. 2015, 29, 336–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertekin, B.; Guzel-Seydim, Z.B. Effect of Fat Replacers on Kefir Quality. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzel-Seydim, Z.B.; Satir, G.; Gokirmakli, C. Use of Mandarin and Persimmon Fruits in Water Kefir Fermentation. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 5890–5897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satir, G.; Guzel-Seydim, Z.B. How Kefir Fermentation Can Affect Product Composition? Small Rumin. Res. 2016, 134, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isleten, M.; Karagul-Yuceer, Y. Effects of Dried Dairy Ingredients on Physical and Sensory Properties of Nonfat Yogurt. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 2865–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabulut, I.; Adnan Hayaloglu, A.; Yildirim, H. Thin-Layer Drying Characteristics of Kurut, a Turkish Dried Dairy by-Product. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 42, 1080–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc, B.; Yilmazer, M.S.; Balkir, P.; Ertekin, F.K. Spray Drying of Yogurt: Optimization of Process Conditions for Improving Viability and Other Quality Attributes. Dry. Technol. 2010, 28, 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocyigit, E.; Abdurakhmanov, R.; Kocyigit, B.F. Potential Role of Camel, Mare Milk, and Their Products in Inflammatory Rheumatic Diseases. Rheumatol. Int. 2024, 44, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirci, A.S.; Gurbuz, B. Fortification of Yoghurt with Xanthan Gum Biosynthesized from Grape Juice Pomace: Physicochemical, Textural and Sensory Characterization. J. Tekirdag Agric. 2023, 20, 1252469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, T. Highlighting the Microbial Community of Kuflu Cheese, an Artisanal Turkish Mold-Ripened Variety, by High-Throughput Sequencing. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2024, 44, 390–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topcu, A.; Bulat, T.; Özer, B. Process Design for Processed Kashar Cheese (a Pasta-Filata Cheese) by Means of Microbial Transglutaminase: Effect on Physical Properties, Yield and Proteolysis. LWT 2020, 125, 109226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuceer, O.; Tuncer, B.O. Determination of antibiotic resistance and biogenic amine production of Lactic Acid bacteria isolated from fermented turkish sausage (Sucuk). J. Food Saf. 2015, 35, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erten, H.; Tanguler, H.; Canbas, A. A Traditional Turkish Lactic Acid Fermented Beverage: Shalgam (Salgam). Food Rev. Int. 2008, 24, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemahlioglu, K.; Kendirci, P.; Kadiroglu, P.; Yucel, U.; Korel, F. Effect of Different Raw Materials on Aroma Fingerprints of ‘boza’ Using an e-Nose and Sensory Analysis. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 2019, 11, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkan, G.; Göktürk Baydar, N. Türk Kırmızı Şaraplarında Fenolik Bileşiklerin Direkt RP-HPLC Ile Belirlenmeleri. Akdeniz Üniv. Ziraat Fak. Derg. 2006, 19, 229–234. [Google Scholar]

- Pekşen, T. Historical Perspectives and Future Directions in Turkey’s Wine Industry: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Master’s Thesis, University of Padova, Padova, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Şafak, B. Türk Bira Sektörü Analizi Ve Türk Bira Firmalarının İhracat Olanakları. Master’s Thesis, Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi, Izmir, Turkey, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Konuray, G.; Erginkaya, Z. Traditional Fermented Food Products of Turkey. In Fermented Food Products; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; pp. 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koparal, A.T. In Vitro Evaluation of Gilaburu (Viburnum opulus L.) Juice on Different Cell Lines. Anadolu J. Educ. Sci. Int. 2019, 9, 549–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budak, N.H.; Aykin, E.; Seydim, A.C.; Greene, A.K.; Guzel-Seydim, Z.B. Functional Properties of Vinegar. J. Food Sci. 2014, 79, R757–R764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, E.; Hasanoglu, A. Removal of Acetic Acid from Aqueous Post-Fermentation Streams and Fermented Beverages Using Membrane Contactors. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2022, 97, 2218–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanlibaba, P. Fermented Nondairy Functional Foods Based on Probiotics. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2023, 35, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, Ö.; Çon, A.H.; Tulumoglu, S. Isolating Lactic Starter Cultures with Antimicrobial Activity for Sourdough Processes. Food Control 2006, 17, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, H.I.; Simsek, O. Characterization of Pediococcus acidilactici PFC69 and Lactococcus lactis PFC77 Bacteriocins and Their Antimicrobial Activities in Tarhana Fermentation. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taşdelen, E.; Şimşek, Ö. The Effects of Ropy Exopolysaccharide-Producing Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Strains on Tarhana Quality. Food Biosci. 2021, 43, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Atri, C. The Role of AI in Microbial Fermentation: Transforming Industrial Applications. Methods Microbiol. 2025, 56, 267–285. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Q.; Qian, J.; Xu, Q.; Guo, Y.; Yao, W.; Qian, H.; Cheng, Y. Integration of Cross-Correlation Analysis and Untargeted Flavoromics Reveals Unique Flavor Formation of Lactic Acid Bacteria Co-Fermented Oat Beverage. Food Biosci. 2024, 59, 103855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkaya, L. Survival of Listeria Monocytogenes in Ayran, a Traditional Turkish Fermented Drink. Mljekarstvo 2015, 65, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altay, F.; Karbancioglu-Guler, F.; Daskaya-Dikmen, C.; Heperkan, D. A Review on Traditional Turkish Fermented Non-Alcoholic Beverages: Microbiota, Fermentation Process and Quality Characteristics. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 167, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgala, A. The Microbiology of Greek/Cyprus Trahanas and of Turkish Tarhana: A Review. Food Sci. Appl. Biotechnol. 2020, 3, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengun, I.Y.; Karapinar, M. Microbiological Quality of Tarhana, Turkish Cereal Based Fermented Food. Qual. Assur. Saf. Crops Foods 2012, 4, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, S.; Gocmen, D.; Kumral, A.Y. A Traditional Turkish Fermented Cereal Food: Tarhana. Food Rev. Int. 2007, 23, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitaf, N.A.; Kirca, D.S.; Simsek, O. The Metagenomic Properties of Uşak Tarhana Dough. Fermentation 2024, 10, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalbantoglu, U.; Cakar, A.; Dogan, H.; Abaci, N.; Ustek, D.; Sayood, K.; Can, H. Metagenomic Analysis of the Microbial Community in Kefir Grains. Food Microbiol. 2014, 41, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilıkkan, Ö.K.; Bağdat, E.Ş. Comparison of Bacterial and Fungal Biodiversity of Turkish Kefir Grains with High-Throughput Metagenomic Analysis. LWT 2021, 152, 112375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirlangic, O.; Ilgaz, C.; Kadiroglu, P. Influence of Pasteurization and Storage Conditions on Microbiological Quality and Aroma Profiles of Shalgam. Food Biosci. 2021, 44, 101350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incedayi, B.; Uylaser, V.; Copur, O.U. A Traditional Turkish Beverage Shalgam: Manufacturing Technique and Nutritional Value. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2008, 6, 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Tanguler, H.; Selli, S.; Sen, K.; Cabaroglu, T.; Erten, H. Aroma Composition of Shalgam: A Traditional Turkish Lactic Acid Fermented Beverage. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 54, 2011–2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanguler, H.; Saris, P.E.J.; Erten, H. Microbial, Chemical and Sensory Properties of Shalgams Made Using Different Production Methods. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2015, 95, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrova, P.; Petrov, K. Traditional Cereal Beverage Boza: Fermentation Technology, Microbial Content and Healthy Effects; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-135179377-3; 978-113863784-9. [Google Scholar]

- Arici, M.; Daglioglu, O. Boza: A Lactic Acid Fermented Cereal Beverage as a Traditional Turkish Food. Food Rev. Int. 2002, 18, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, H.; Erkmen, O. Effects of Starter Cultures and Additives on the Quality of Turkish Style Sausage (Sucuk). Meat Sci. 2002, 61, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdal, T. Changes in Physicochemical, Microbiological and Sensory Characteristics of Traditionally Produced Turkish Sucuk During Ripening and Storage: Natural or Synthetic Additives? J. Food 2020, 45, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Soyuçok, A. Metagenomic Analysis of Microbial Diversity in Sucuk, a Traditional Turkish Dry-Fermented Sausage, and Its Relationship with Organic Acid Compounds. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2025, 37, 396–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaman, H.; Elmali, M.; Karadagoglu, G.; Cetinkaya, A. Observations of Kefir Grains and Their Structure from Different Geographical Regions: Turkey and Germany. Atatürk Üniv. Vet. Bil. Derg 2006, 1, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ozlu, H.; Atasever, M. Bacteriocinogenic Bacteria Isolated from Civil, Kashar and White Cheeses in Erzurum, Turkey. Ank. Univ. Vet. Fak. Derg. 2019, 66, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudağidan, M.; Mediha Nur, Z.Y.; Taşbaşi, B.B.; Acar, E.E.; Ömeroğlu, E.E.; Uçak, S.; Özalp, V.C.; Aydin, A. 16S Bacterial Metagenomic Analysis of Herby Cheese (Otlu Peynir) Microbiota. Acta Vet. Eurasia 2021, 47, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekici, K.; Okut, H.; Isleyici, O.; Sancak, Y.C.; Tuncay, R.M. The Determination of Some Microbiological and Chemical Features in Herby Cheese. Foods 2019, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ma, T.; Liang, Q.; Sun, J.; Wu, X.; Song, Y.; Nie, H.; Huang, J.; Mu, G. Fermented Dairy Products as Precision Modulators of Gut Microbiota and Host Health: Mechanistic Insights, Clinical Evidence, and Future Directions. Foods 2025, 14, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherbal, A.; Abboud, Y.; Lakroun, R.; Nafa, D.; Aytar, E.C.; Khaldi, S. Unlocking the Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Sourdough: Phytochemical Profile, Functional Investigation, and Molecular Docking Insights into Key Bioactive Compounds. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2025, 80, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Portillo, K.A.; Hernández-Miranda, J.; Ricaño-Rodríguez, J.; López-Perea, P.; Román-Gutiérrez, A.D. Exploring the Anti-Proliferative Effects of Cereal-Derived Functional Beverages via Bioactive Compound Profiling. Discov. Food 2025, 5, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cem Eraslan, E. A Study on Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Potential of Kahramanmaraş Tarhana. Int. J. Chem. Technol 2024, 8, 159–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman Ilıkkan, Ö. Effect of Hardaliye on FoxM1 Gene Expression Level of HT-29, DU-145, HeLa Cancer Cells and CF-1 (Mouse Embryonic Fibroblast). Akad. Dergiler 2017, 2, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulger, H.; Ertekin, T.; Karaca, O.; Canoz, O.; Nisari, M.; Unur, E.; Elmalı, F. Influence of Gilaburu (Viburnum opulus) Juice on 1,2-Dimethylhydrazine (DMH)-Induced Colon Cancer. Toxicol. Ind. Health 2013, 29, 824–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badem, A.; Fidan, E. An Evaluation of Turkey’s Geographically Indicated Sourdough Breads. J. Abant Soc. Sci. 2025, 2025, 478–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işık Doğan, Ö.; Yılmaz, R. Tarhana Microbiota–Metabolome Relationships: An Integrative Analysis of Multi-Omics Data. Food Biotechnol. 2023, 37, 191–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yegin, Z.; Yurt, M.N.Z.; Tasbasi, B.B.; Acar, E.E.; Altunbas, O.; Ucak, S.; Ozalp, V.C.; Sudagidan, M. Determination of Bacterial Community Structure of Turkish Kefir Beverages via Metagenomic Approach. Int. Dairy J. 2022, 129, 105337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik Doğan, C.; Yüksel Dolgun, H.T.; İkiz, S.; Kırkan, Ş.; Parın, U. Detection of the Microbial Composition of Some Commercial Fermented Liquid Products via Metagenomic Analysis. Foods 2023, 12, 3538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadiroglu, H.; Cetin, B. Identification of Bacterial Microbiota of Traditional Homemade Vinegars. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2023, 62, 354–362. [Google Scholar]

- Aksoy, S.; Kayili, H.M.; Atakay, M.; Kirmaci, H.A.; Salih, B. Dynamics of Peptides Released from Cow Milk Fermented by Kefir Microorganisms during Fermentation and Storage Periods. Int. Dairy J. 2024, 155, 105970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Hou, J.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, M. Research on How Human Intelligence, Consciousness, and Cognitive Computing Affect the Development of Artificial Intelligence. Complexity 2020, 2020, 1680845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, C.S.; Zahia-Azizan, N.A.; Abd Rahim, M.H.; Mohd Zaini, N.A.; Raja-Razali, R.B.; Ushidee-Radzi, M.A.; Ilham, Z.; Wan-Mohtar, W.A.A.Q.I. Smart Fermentation Technologies: Microbial Process Control in Traditional Fermented Foods. Fermentation 2025, 11, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niyigaba, T.; Küçükgöz, K.; Kołożyn-Krajewska, D.; Królikowski, T.; Trząskowska, M. Advances in Fermentation Technology: A Focus on Health and Safety. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K. Artificial Neural Networks Industrial and Control Engineering; Intech Open: London, UK, 2011; p. 490. ISBN 9789533072203. [Google Scholar]

- Seesaard, T.; Wongchoosuk, C. Recent Progress in Electronic Noses for Fermented Foods and Beverages Applications. Fermentation 2022, 8, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıkmış, S.; Duman Altan, A.; Türkol, M.; Gezer, G.E.; Ganimet, Ş.; Abdi, G.; Hussain, S.; Aadil, R.M. Effects on Quality Characteristics of Ultrasound-Treated Gilaburu Juice Using RSM and ANFIS Modeling with Machine Learning Algorithm. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2024, 107, 106922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kahraman Ilıkkan, Ö.; Bağdat, E.Ş.; Yılmaz, R.; Çetin, B.; Çon, A.H.; Erten, H.; Göksungur, M.Y.; Şimşek, Ö. Bridging Tradition and Innovation: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis of Turkish Fermented Foods. Foods 2025, 14, 4324. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244324

Kahraman Ilıkkan Ö, Bağdat EŞ, Yılmaz R, Çetin B, Çon AH, Erten H, Göksungur MY, Şimşek Ö. Bridging Tradition and Innovation: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis of Turkish Fermented Foods. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4324. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244324

Chicago/Turabian StyleKahraman Ilıkkan, Özge, Elif Şeyma Bağdat, Remziye Yılmaz, Bülent Çetin, Ahmet Hilmi Çon, Hüseyin Erten, Mehmet Yekta Göksungur, and Ömer Şimşek. 2025. "Bridging Tradition and Innovation: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis of Turkish Fermented Foods" Foods 14, no. 24: 4324. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244324

APA StyleKahraman Ilıkkan, Ö., Bağdat, E. Ş., Yılmaz, R., Çetin, B., Çon, A. H., Erten, H., Göksungur, M. Y., & Şimşek, Ö. (2025). Bridging Tradition and Innovation: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis of Turkish Fermented Foods. Foods, 14(24), 4324. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244324