Characterization of Biofilm-Forming Lactic Acid Bacteria from Traditional Fermented Foods and Their Probiotic Potential

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Isolates and Culture Conditions

2.2. Preparation of Planktonic and Biofilm Cells

2.3. Biofilm Formation Assay

2.4. Observation Using the Fluorescent Inverted Microscope

2.5. Acid Tolerance Assay

2.6. Bile Salt Tolerance Assay

2.7. In Vitro Gastrointestinal Tolerance Assay

2.8. Adhesion to Caco-2 Cells Assay

2.9. Identification of Bacteria

2.10. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) of Planktonic and Biofilm Bacteria

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Ability of LAB to Form Biofilms

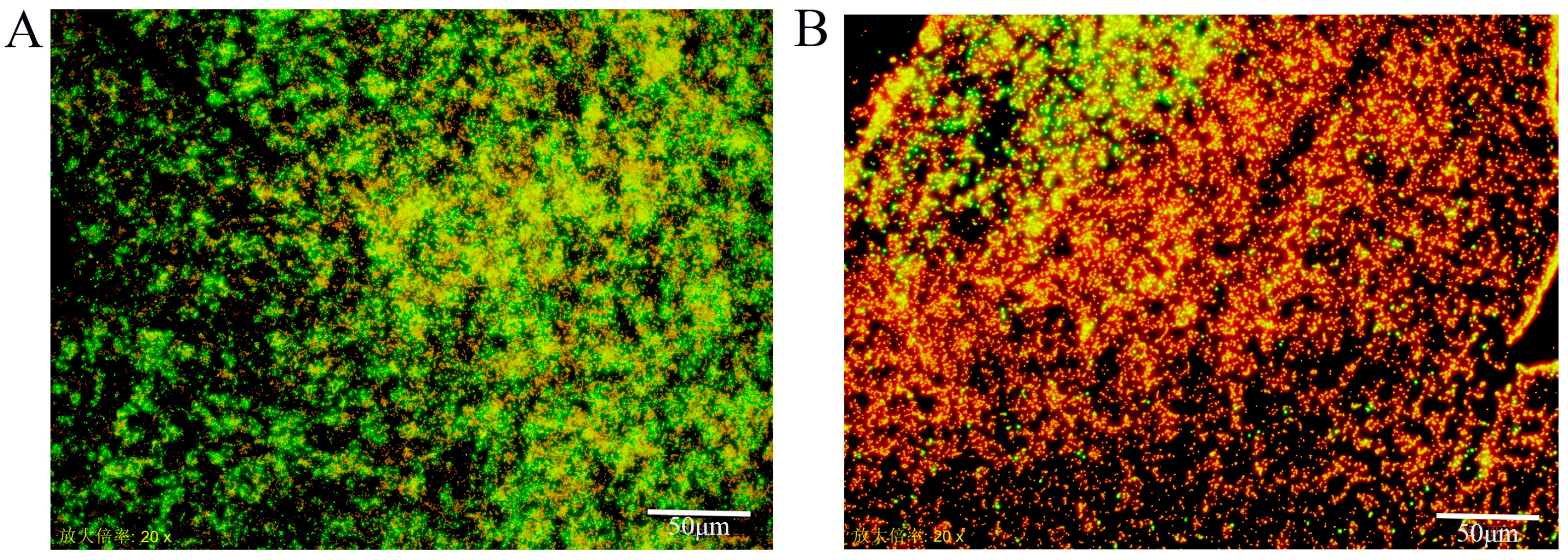

3.2. Fluorescent Microscope Assay

3.3. Tolerance of LAB with High Biofilm Production to Different Types of Environmental Stress

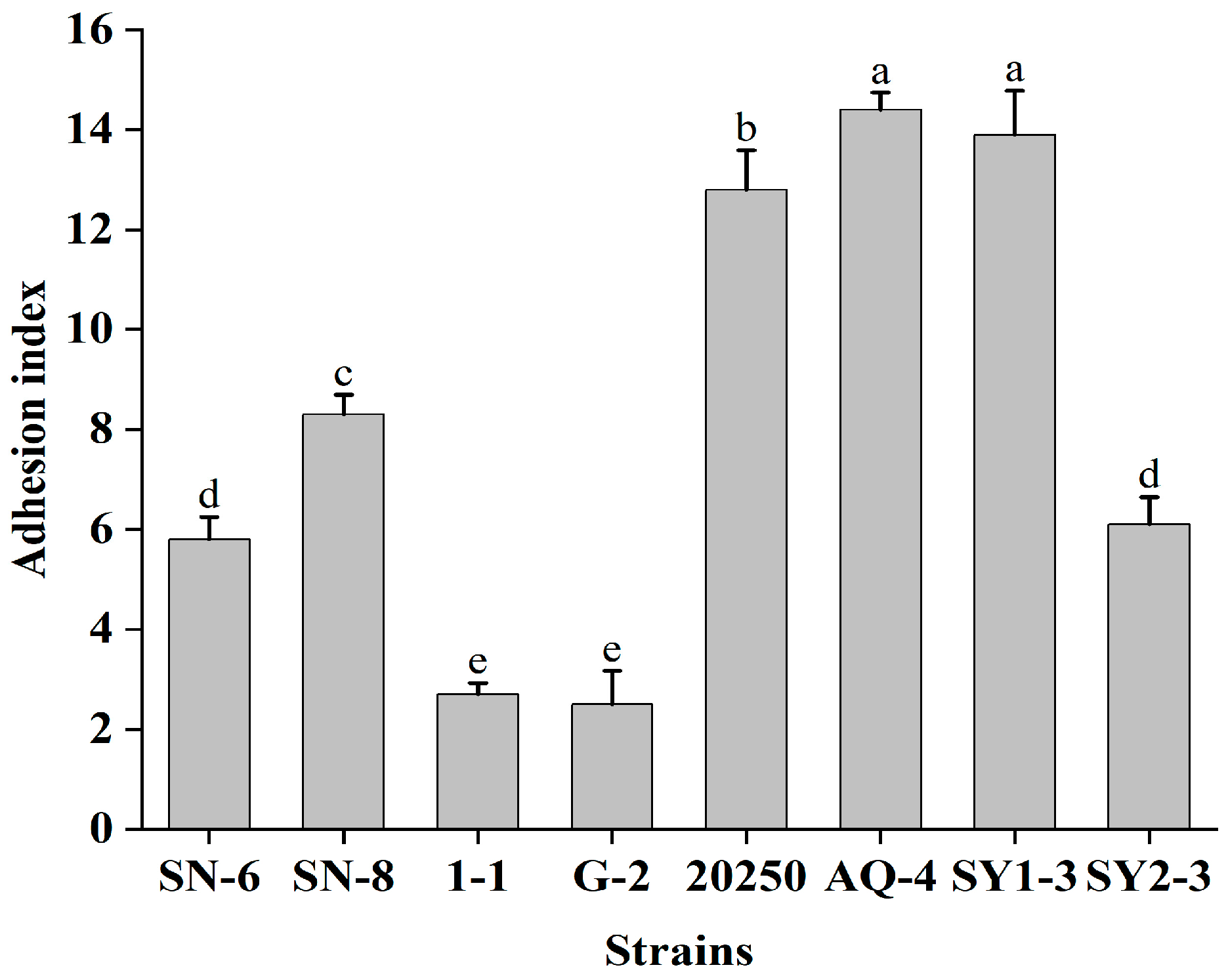

3.4. Adherence to Caco-2 Cells

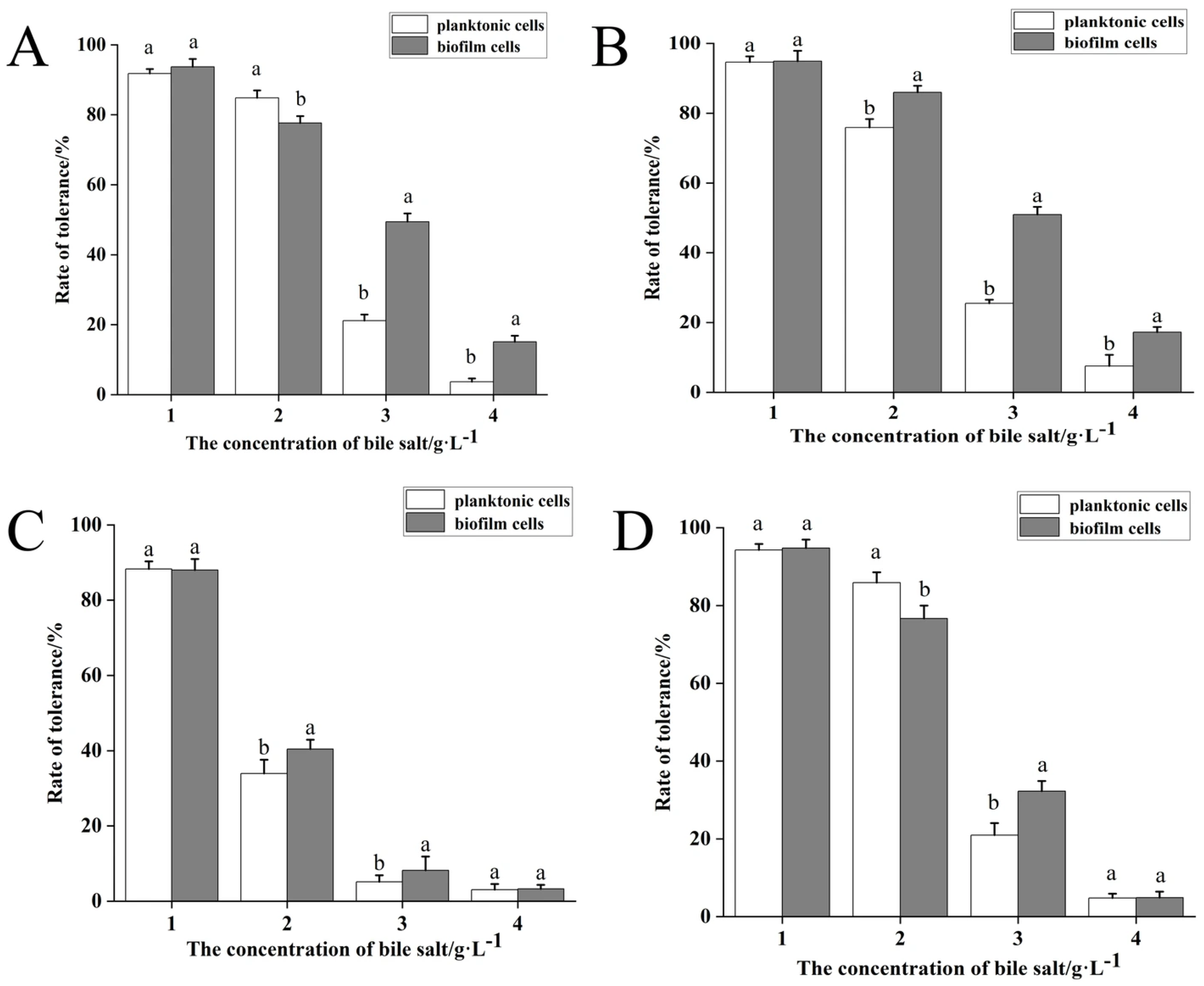

3.5. Stress Tolerance in Planktonic vs. Biofilm States

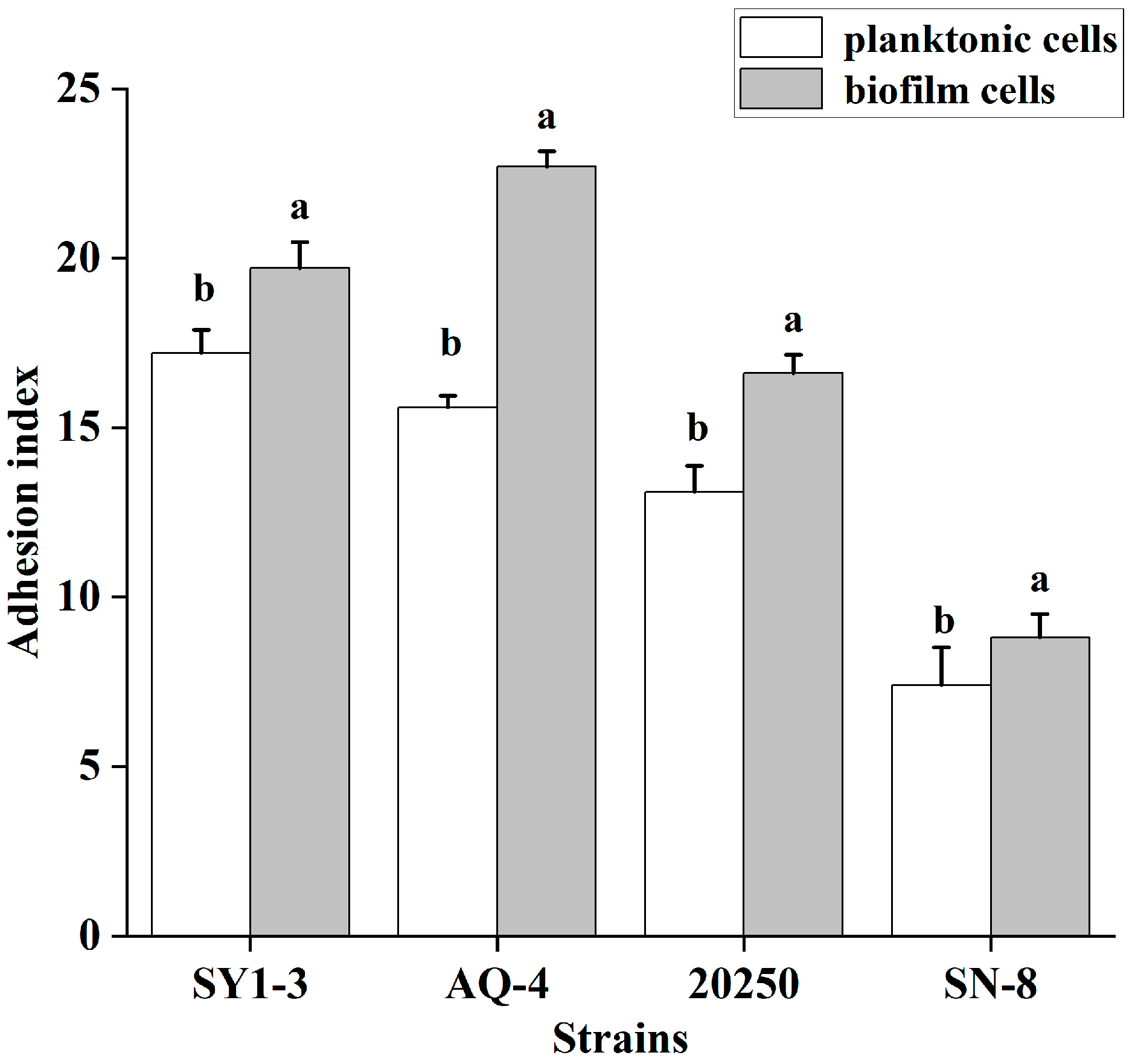

3.6. Adherence to Caco-2 Cells in the Planktonic and Biofilm States

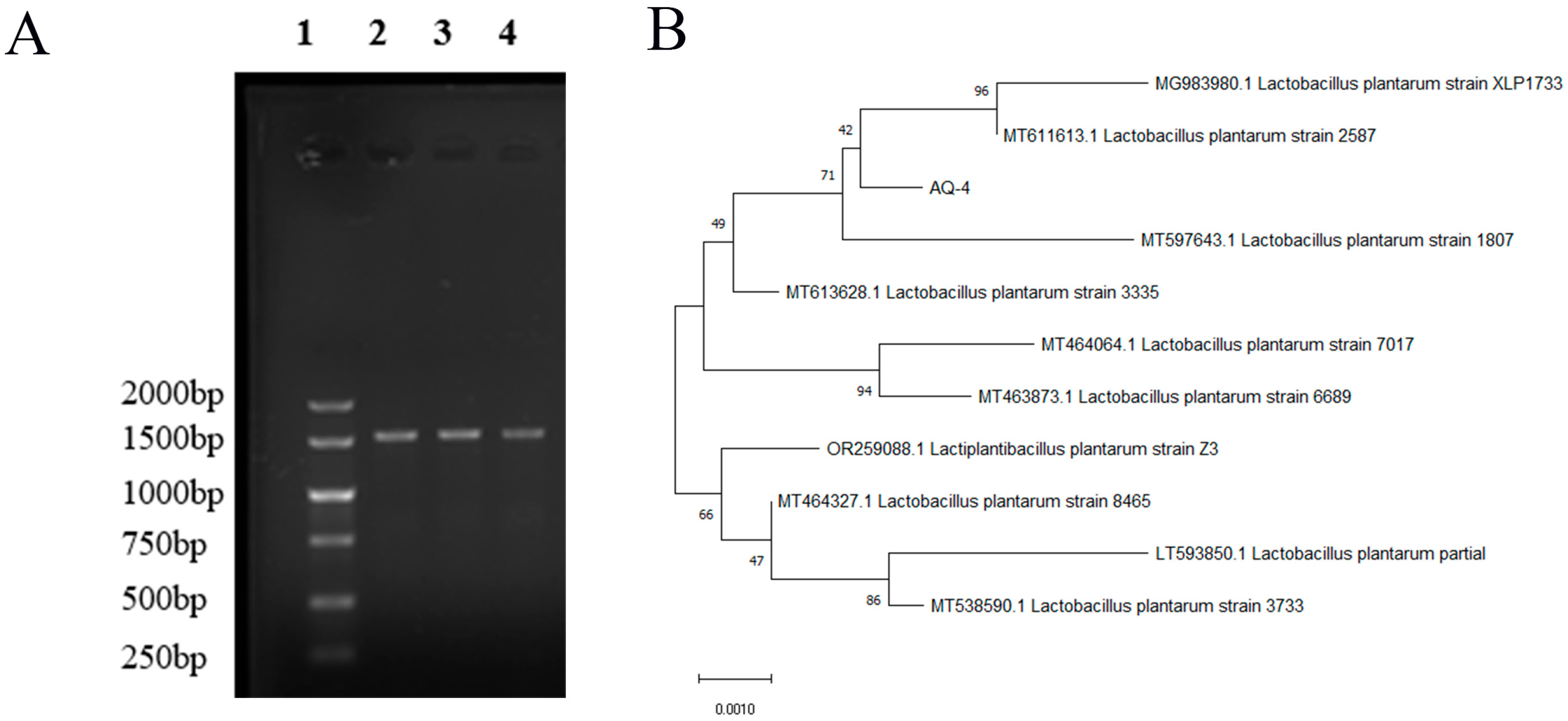

3.7. Identification of LAB

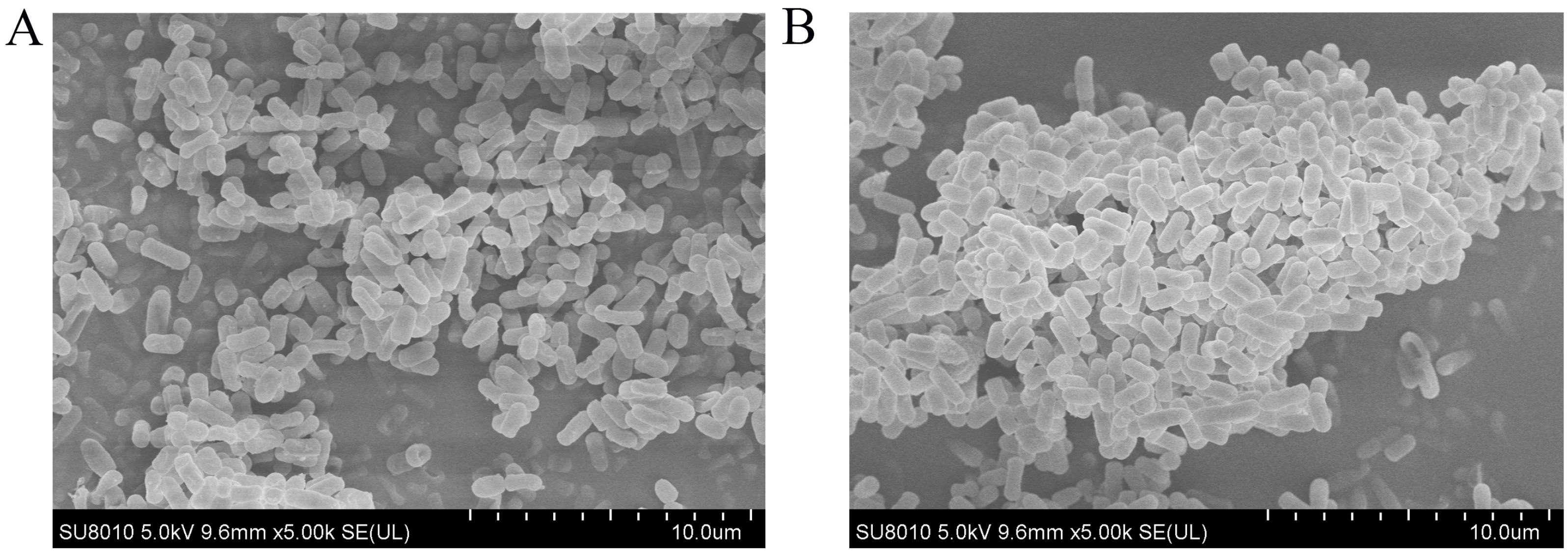

3.8. Microstructure of L. plantarum AQ-4 in Different States

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zapasnik, A.; Sokolowska, B.; Bryla, M. Role of Lactic Acid Bacteria in Food Preservation and Safety. Foods 2022, 11, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angmo, K.; Kumari, A.; Savitri Bhalla, T. Probiotic characterization of lactic acid bacteria isolated from fermented foods and beverage of Ladakh. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 66, 428–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abushelaibi, A.; Al-Mahadin, S.; El-Tarabily, K.; Shah, N.; Ayyash, M. Characterization of potential probiotic lactic acid bacteria isolated from camel milk. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 79, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Wei, Z.; Yin, B.; Man, C.; Jiang, Y. Enhancement of functional characteristics of blueberry juice fermented by Lactobacillus plantarum. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 139, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Cui, Y.; Jia, Q.; Zhuang, Y.; Gu, Y.; Fan, X.; Ding, Y. Response mechanisms of lactic acid bacteria under environmental stress and their application in the food industry. Food Biosci. 2025, 64, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO. Joint FAO/WHO Working Group Report on Drafting Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food; FAO/WHO: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Muthukumarasamy, P.; Allan-Wojtas, P.; Holley, R. Stability of Lactobacillus reuteri in different types of microcapsules. J. Food Sci. 2006, 71, M20–M24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.; Ruiz, M.; Lasserrot, A.; Hormigo, M.; Morales, M. An improved ionic gelation method to encapsulate Lactobacillus spp. bacteria: Protection, survival and stability study. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 69, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Han, M.; Fei, T.; Liu, H.; Gai, Z. Utilization of diverse oligosaccharides for growth by Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species and their in vitro co-cultivation characteristics. Int. Microbiol. 2024, 27, 941–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Sun, Y.; Chen, C.; Sun, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, F.; Zhang, H.; Dai, Y. Genome shuffling of Lactobacillus plantarum for improving antifungal activity. Food Control 2013, 32, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Sampers, I.; Van de Walle, D.; Dewettinck, K.; Raes, K. Encapsulation of Lactobacillus in Low-Methoxyl Pectin-Based Microcapsules Stimulates Biofilm Formation: Enhanced Resistances to Heat Shock and Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 6281–6290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, G.; Kaplan, H.; Kolter, R. Biofilm formation as microbial development. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2000, 54, 49–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flemming, H.; Wuertz, S. Bacteria and archaea on Earth and their abundance in biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubota, H.; Senda, S.; Nomura, N.; Tokuda, H.; Uchiyama, H. Biofilm Formation by Lactic Acid Bacteria and Resistance to Environmental Stress. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2008, 106, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, M.; Smid, E.; Abee, T.; Groot, M. Characterisation of biofilms formed by Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1 and food spoilage isolates. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 207, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mgomi, F.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, G.; Yang, Z. Lactic acid bacteria biofilms and their antimicrobial potential against pathogenic microorganisms. Biofilm 2023, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Jara, M.; Ilabaca, A.; Vega, M.; García, A. Biofilm Forming Lactobacillus: New Challenges for the Development of Probiotics. Microorganisms 2016, 4, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Guo, S.; Chen, X.; Yang, S.; Deng, X.; Tu, M.; Tao, Y.; Xiang, W.; Rao, Y. Metabolic profiles of Lactobacillus paraplantarum in biofilm and planktonic states and investigation of its intestinal modulation and immunoregulation in dogs. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 5317–5332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Zakir, M.; Khanam, Z.; Shakil, S.; Khan, A. Novel compound from Trachyspermum ammi (Ajowan caraway) seeds with antibiofilm and antiadherence activities against Streptococcus mutans: A potential chemotherapeutic agent against dental caries. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 109, 2151–2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Ding, Y.; Ma, Z.; Jiang, F.; Nie, X.; Tang, S.; Chen, M.; Wu, S.; et al. Prevalence, antibiotic susceptibility and genetic diversity of Campylobacter jejuni isolated from retail food in China. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 143, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, N.; Mizan, M.; Jahid, I.; Ha, S. Biofilm formation by Vibrio parahaemolyticus on food and food contact surfaces increases with rise in temperature. Food Control 2016, 70, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Qin, S.; Huang, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W. Inhibitory and preventive effects of Lactobacillus plantarum FB-T9 on dental caries in rats. J. Oral Microbiol. 2020, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.; Jung, D. Evaluation of probiotic properties of Lactobacillus and Pediococcus strains isolated from Omegisool, a traditionally fermented millet alcoholic beverage in Korea. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 63, 437–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minekus, M.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu, C.; Carrière, F.; Boutrou, R.; Corredig, M.; Dupont, D.; et al. A standardised static in vitro digestion method suitable for food—An international consensus. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Q. Ability of Lactobacillus to inhibit enteric pathogenic bacteria adhesion on Caco-2 cells. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 27, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Guarner, F.; Reid, G.; Gibson, G.; Merenstein, D.; Pot, B.; Morelli, L.; Canani, R.; Flint, H.; Salminen, S.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, M.; De Grandi, R.; Pastorelli, L.; Vecchi, M.; Drago, L. A consumer’s guide for probiotics: 10 golden rules for a correct use. Dig. Liver Dis. 2017, 49, 1177–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotter, P.; Hill, C. Surviving the acid test: Responses of gram-positive bacteria to low pH. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003, 67, 429–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, D.O.; Gillilands, S.E. Influence of Bile on Cellular Integrity and Beta-Galactosidase Activity of Lactobacillus acidophilus. J. Dairy. Sci. 1993, 76, 1253–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Lee, J.; Lim, S.; Kim, Y.; Lee, N.; Paik, H. Antioxidant and immune-enhancing effects of probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum 200655 isolated from kimchi. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2019, 28, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Dong, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H. Screening of potential probiotic properties of Lactobacillus fermentum isolated from traditional dairy products. Food Control 2010, 21, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, C.; Thorsen, L.; Schwan, R.; Jespersen, L. Strain-specific probiotics properties of Lactobacillus fermentum, Lactobacillus plantarum and Lactobacillus brevis isolates from Brazilian food products. Food Microbiol. 2013, 36, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argyri, A.; Zoumpopoulou, G.; Karatzas, K.; Tsakalidou, E.; Nychas, G.; Panagou, E.; Tassou, C. Selection of potential probiotic lactic acid bacteria from fermented olives by in vitro tests. Food Microbiol. 2013, 33, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikmaram, P.; Mousavi, S.; Emam-Djomeh, Z.; Kiani, H.; Razavi, S. Evaluation and prediction of metabolite production, antioxidant activities, and survival of Lactobacillus casei 431 in a pomegranate juice supplemented yogurt drink using support vector regression. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2015, 24, 2105–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, K.; Sugiyama, M.; Mukai, T. Adhesion Properties of Lactic Acid Bacteria on Intestinal Mucin. Microorganisms 2016, 4, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krausova, G.; Hynstova, I.; Svejstil, R.; Mrvikova, I.; Kadlec, R. Identification of Synbiotics Conducive to Probiotics Adherence to Intestinal Mucosa Using an In Vitro Caco-2 and HT29-MTX Cell Model. Processes 2021, 9, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Zhao, D.; Zhou, R.; Zheng, J.; Wu, C. Characterization and Multi-Omics Basis of Biofilm Formation by Lactiplantibacillus plantarum. Fermentation 2025, 11, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, H.; Senda, S.; Tokuda, H.; Uchiyama, H.; Nomura, N. Stress resistance of biofilm and planktonic Lactobacillus plantarum subsp. plantarum JCM 1149. Food Microbiol. 2009, 26, 592–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gu, Y.; Wu, R.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Nie, L.; Qiao, R.; He, Y. Exploring the relationship between the signal molecule AI-2 and the biofilm formation of Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 154, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Zheng, H.; Sun, S.; Pang, X.; Liang, Y.; Shang, J.; Zhu, Z.; Meng, X. Role of luxS in Stress Tolerance and Adhesion Ability in Lactobacillus plantarum KLDS1.0391. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 4506829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulter, R.; Gentle, I.; Dykes, G. Characterisation of Curli Production, Cell Surface Hydrophobicity, Autoaggregation and Attachment Behaviour of Escherichia coli O157. Curr. Microbiol. 2010, 61, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banic, M.; Uroic, K.; Pavunc, A.; Novak, J.; Zoric, K.; Durgo, K.; Petkovic, H.; Jamnik, P.; Kazazic, S.; Kazazic, S.; et al. Characterization of S-layer proteins of potential probiotic starter culture Lactobacillus brevis SF9B isolated from sauerkraut. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 93, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Man, C.; Jiang, Y. Characterization and transcriptomic basis of biofilm formation by Lactobacillus plantarum J26 isolated from traditional fermented dairy products. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 125, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Isolation Source (n) | Specific Source | Strong (OD570 > 0.544) | Moderate (OD570 0.272–0.544) | Weak (OD570 0.136–0.271) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pickled vegetables (62) | Cabbage, radish, cucumber, asparagus lettuce, mustard leaf, carrot, yam, pepper, celery, green bean | H-2, 20250, 1-1, 1-2, 7-1, A-1, A-2, B-1, G-2 | 10-4, PCB-3, 14-2, 10-3, 2-1, 4-3, B-3, G-3, I-3, PCB-1, PCB-4 | 2-2, 3-1, 3-2, 3-3, 3-5, 4-1, 4-2, 4-4, 5-1, 5-2, 5-3, 5-4, 6-1, 6-2, 6-3, 6-4, 7-2, 7-3, 7-4, 9-1, 9-2, 9-3, 10-1, D-1, D-2, F-3, J-1, Q-1, Q-2, Q-3, Q-4, Q-5, FG-1, NO, PT1, PT2, PCB-2, PCH-1, PCH-2, PCG-1, PCG-2, PCG-3 |

| Yogurt (11) | Fermented milk products originated from Tibet regions of China. | SN-8, SN-6, YLD-LC | – | XN-3, XN-4, D1, SN-1, SN-2, XN-1, XN-2, XN-5 |

| Fermented juices (17) | Pear, apple, grape, pomegranate, fig | SY2-3, AQ-4, SY1-3 | AQ-5, AQ-7 | AQ-2, AQ-3, AQ-6, 21805, SC-2, SC-3, LMJS-1, SY1-1, SY2-1, SY2-2, SY3-1, SY1-4 |

| Total (90) | 15 (16.7%) | 13 (14.4%) | 62 (68.9%) |

| Product Category | Specific Source | Isolate ID | BFI (Mean ± SD) | Biofilm Formation Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pickled vegetable | cabbage | 1-1 | 5.512 ± 0.102 | strong |

| cabbage | 1-2 | 0.073 ± 0.012 | weak | |

| cabbage | A-1 | 0.442 ± 0.034 | weak | |

| cabbage | A-2 | 0.081 ± 0.009 | weak | |

| radish | 2-1 | 0.570 ± 0.037 | weak | |

| cucumber | 4-3 | 0.523 ± 0.045 | weak | |

| pepper | G-2 | 3.094 ± 0.072 | strong | |

| carrot | 20250 | 2.980 ± 0.055 | strong | |

| yam | PCG-1 | 1.324 ± 0.036 | moderate | |

| yam | PCB-3 | 1.509 ± 0.057 | moderate | |

| mustard leaf | 10-4 | 0.880 ± 0.019 | moderate | |

| mustard leaf | 10-3 | 0.357 ± 0.024 | weak | |

| celery | H-2 | 0.378 ± 0.035 | weak | |

| radish | B-1 | 0.169 ± 0.013 | weak | |

| asparagus lettuce | 7-1 | 0.436 ± 0.037 | weak | |

| green bean | PT1 | 0.567 ± 0.023 | weak | |

| naturally fermented juice | pear | AQ-4 | 6.181 ± 0.077 | strong |

| apple | SY2-3 | 5.645 ± 0.087 | strong | |

| apple | SY1-3 | 10.206 ± 0.115 | strong | |

| fig | 21805 | 0.760 ± 0.039 | moderate | |

| yogurt | milk | SN-8 | 4.924 ± 0.098 | strong |

| milk | SN-6 | 4.339 ± 0.091 | strong | |

| milk | XN-1 | 0.114 ± 0.021 | weak | |

| milk | YLD-LC | 0.106 ± 0.015 | weak | |

| milk | D1 | 0.102 ± 0.008 | weak |

| pH2 | pH3 | pH4 | pH5 | pH6 | pH7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-1 | 0.111 ± 0.004 a | 0.107 ± 0.002 a | 1.873 ± 0.14 | 1.949 ± 0.07 | 1.959 ± 0.11 | 1.976 ± 0.02 |

| G-2 | 0.154 ± 0.005 b | 0.304 ± 0.007 b | 1.922 ± 0.11 | 1.961 ± 0.04 | 1.971 ± 0.08 | 1.977 ± 0.06 |

| SN-6 | 0.183 ± 0.003 c | 0.466 ± 0.02 c | 1.833 ± 0.07 | 1.949 ± 0.09 | 1.959 ± 0.07 | 1.976 ± 0.08 |

| SN-8 | 0.153 ± 0.006 b | 0.299 ± 0.008 b | 1.855 ± 0.07 | 1.959 ± 0.12 | 1.97 ± 0.03 | 1.978 ± 0.06 |

| SY1-3 | 0.129 ± 0.002 d | 0.52 ± 0.04 d | 1.841 ± 0.09 | 1.936 ± 0.05 | 1.961 ± 0.13 | 1.966 ± 0.03 |

| SY2-3 | 0.123 ± 0.005 d | 0.375 ± 0.03 e | 1.833 ± 0.08 | 1.965 ± 0.08 | 1.97 ± 0.06 | 1.976 ± 0.10 |

| AQ-4 | 0.154 ± 0.003 b | 0.461 ± 0.04 c | 1.875 ± 0.12 | 1.932 ± 0.06 | 1.952 ± 0.08 | 1.958 ± 0.07 |

| 20250 | 0.181 ± 0.004 c | 0.432 ± 0.02 c | 1.807 ± 0.06 | 1.952 ± 0.12 | 1.966 ± 0.09 | 1.981 ± 0.08 |

| 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.4% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-1 | 86.90 ± 1.56 d | 12.57 ± 0.56 d | 10.00 ± 0.45 d | 8.33 ± 0.35 d |

| G-2 | 96.22 ± 1.34 a | 79.21 ± 1.23 b | 56.64 ± 1.02 b | 25.26 ± 0.46 c |

| SN-6 | 94.57 ± 1.89 b | 6.40 ± 0.58 e | 6.30 ± 0.77 e | 5.23 ± 0.29 e |

| SN-8 | 97.54 ± 1.23 a | 81.26 ± 1.32 b | 57.85 ± 1.18 b | 55.15 ± 0.77 a |

| SY1-3 | 94.15 ± 1.45 b | 79.36 ± 1.17 b | 42.58 ± 1.21 c | 43.83 ± 0.62 b |

| SY2-3 | 93.20 ± 1.67 b | 6.53 ± 0.77 e | 6.20 ± 0.55 e | 5.40 ± 0.33 e |

| AQ-4 | 96.79 ± 1.22 a | 84.41 ± 1.76 a | 65.95 ± 0.89 a | 44.46 ± 0.49 b |

| 20250 | 90.67 ± 1.08 c | 58.71 ± 1.12 c | 43.20 ± 0.75 c | 24.96 ± 0.32 c |

| 1-1 | G-2 | SN-6 | SN-8 | SY1-3 | SY2-3 | AQ-4 | 20250 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastric fluid | 1.40 ± 0.02 e | 4.15 ± 0.06 d | 4.00 ± 0.05 d | 28.70 ± 0.36 a | 10.50 ± 0.32 c | 23.65 ± 0.38 b | 11.70 ± 0.19 c | 29.30 ± 0.28 a |

| Intestinal fluid | 48.8 ± 0.22 c | 46.2 ± 0.45 c | 15.5 ± 0.12 e | 62.2 ± 0.55 b | 65.2 ± 0.42 b | 30.3 ± 0.27 d | 75.95 ± 0.62 a | 47.7 ± 0.45 c |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yao, P.; Kang, M.; Effarizah, M.E. Characterization of Biofilm-Forming Lactic Acid Bacteria from Traditional Fermented Foods and Their Probiotic Potential. Foods 2025, 14, 4299. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244299

Yao P, Kang M, Effarizah ME. Characterization of Biofilm-Forming Lactic Acid Bacteria from Traditional Fermented Foods and Their Probiotic Potential. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4299. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244299

Chicago/Turabian StyleYao, Peilin, Min Kang, and Mohd Esah Effarizah. 2025. "Characterization of Biofilm-Forming Lactic Acid Bacteria from Traditional Fermented Foods and Their Probiotic Potential" Foods 14, no. 24: 4299. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244299

APA StyleYao, P., Kang, M., & Effarizah, M. E. (2025). Characterization of Biofilm-Forming Lactic Acid Bacteria from Traditional Fermented Foods and Their Probiotic Potential. Foods, 14(24), 4299. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244299