Bioactive Protein Profile and Compositional Evolution of Donkey Milk Across Lactation Reflecting Its Nutritional and Functional Food Value

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Considerations

2.2. Management Practices and Milk Sampling

2.3. Determination of Milk Chemical Composition

2.4. Quantification of Bioactive Proteins

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

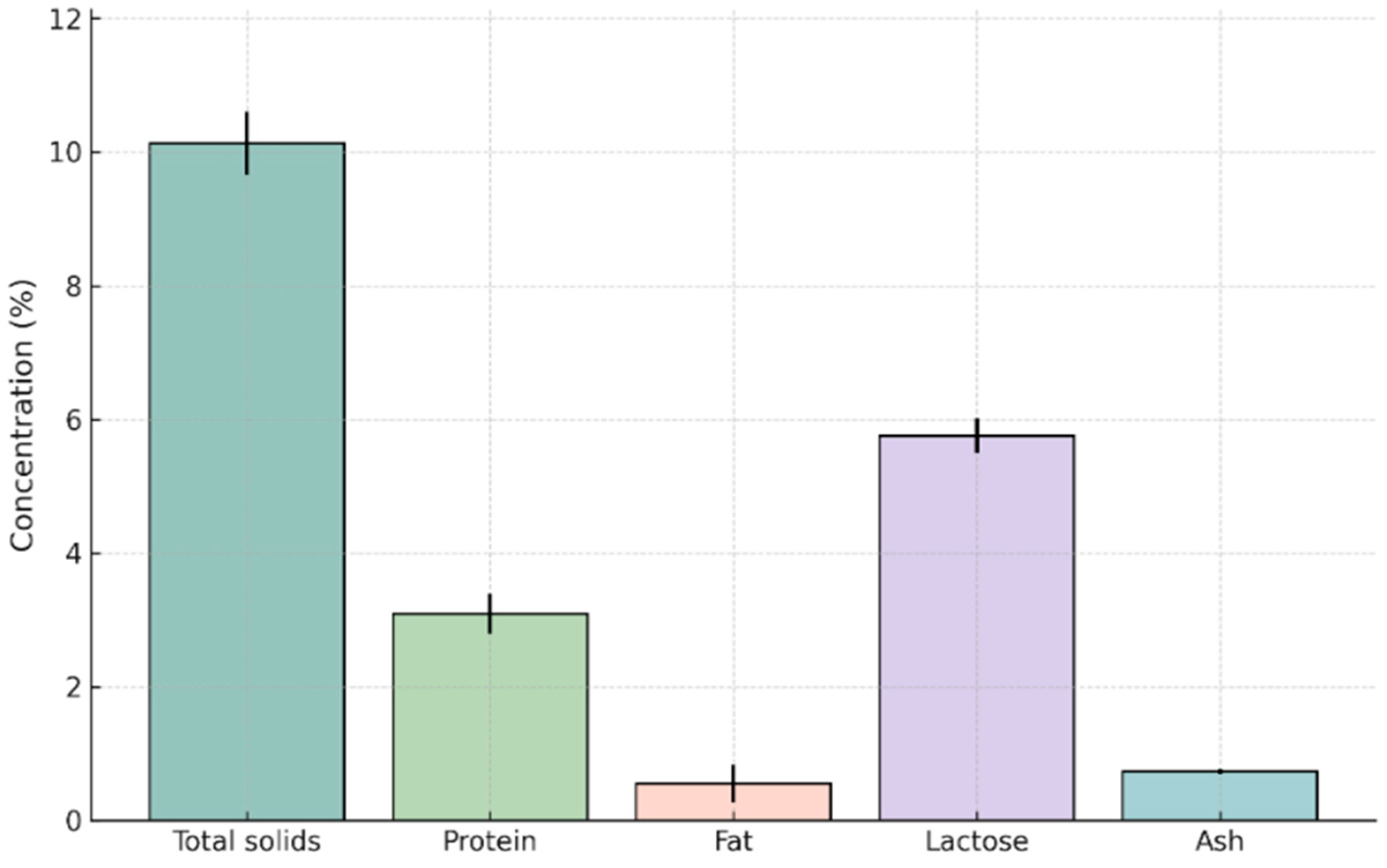

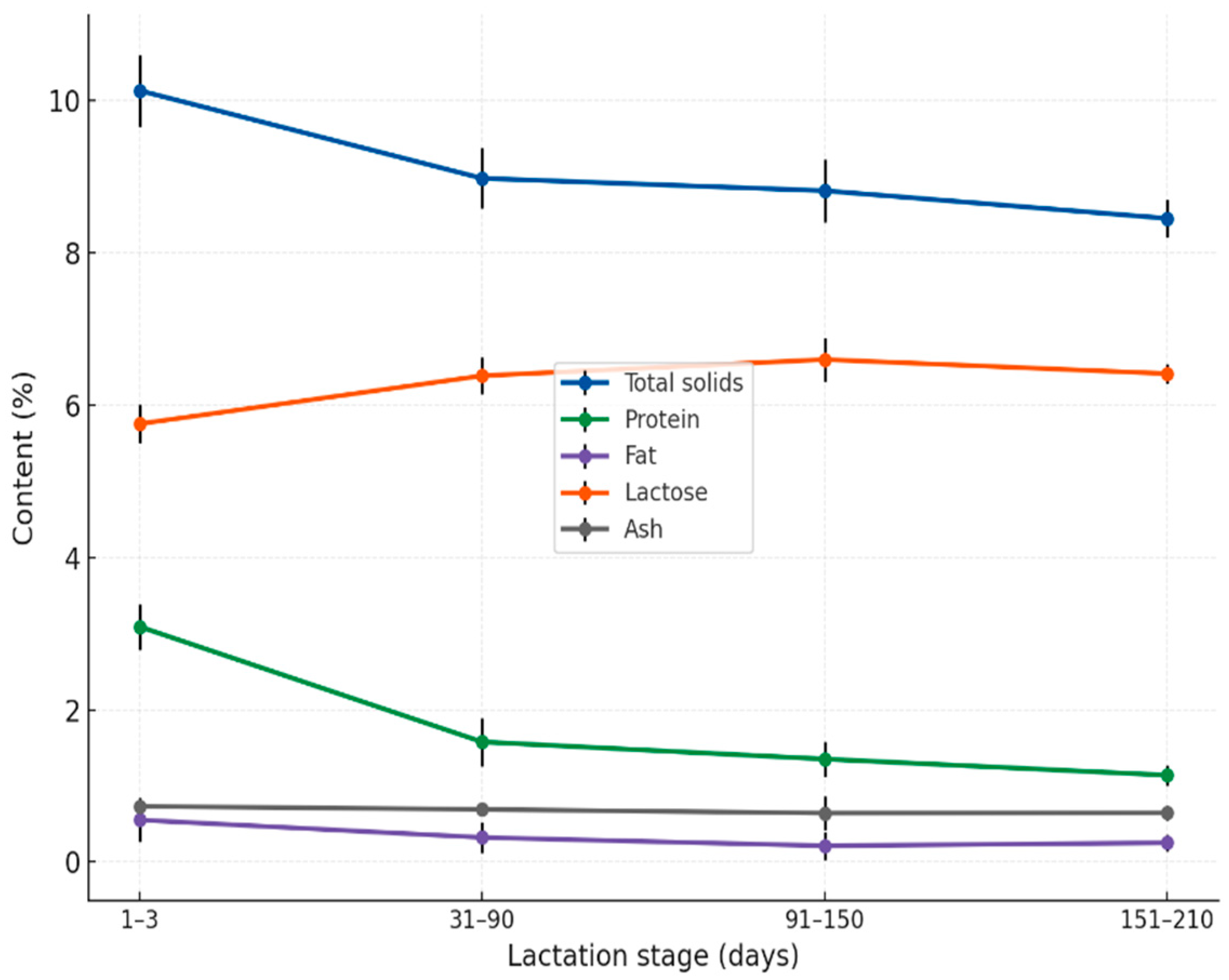

3.1. Chemical Composition Across Lactation Stages

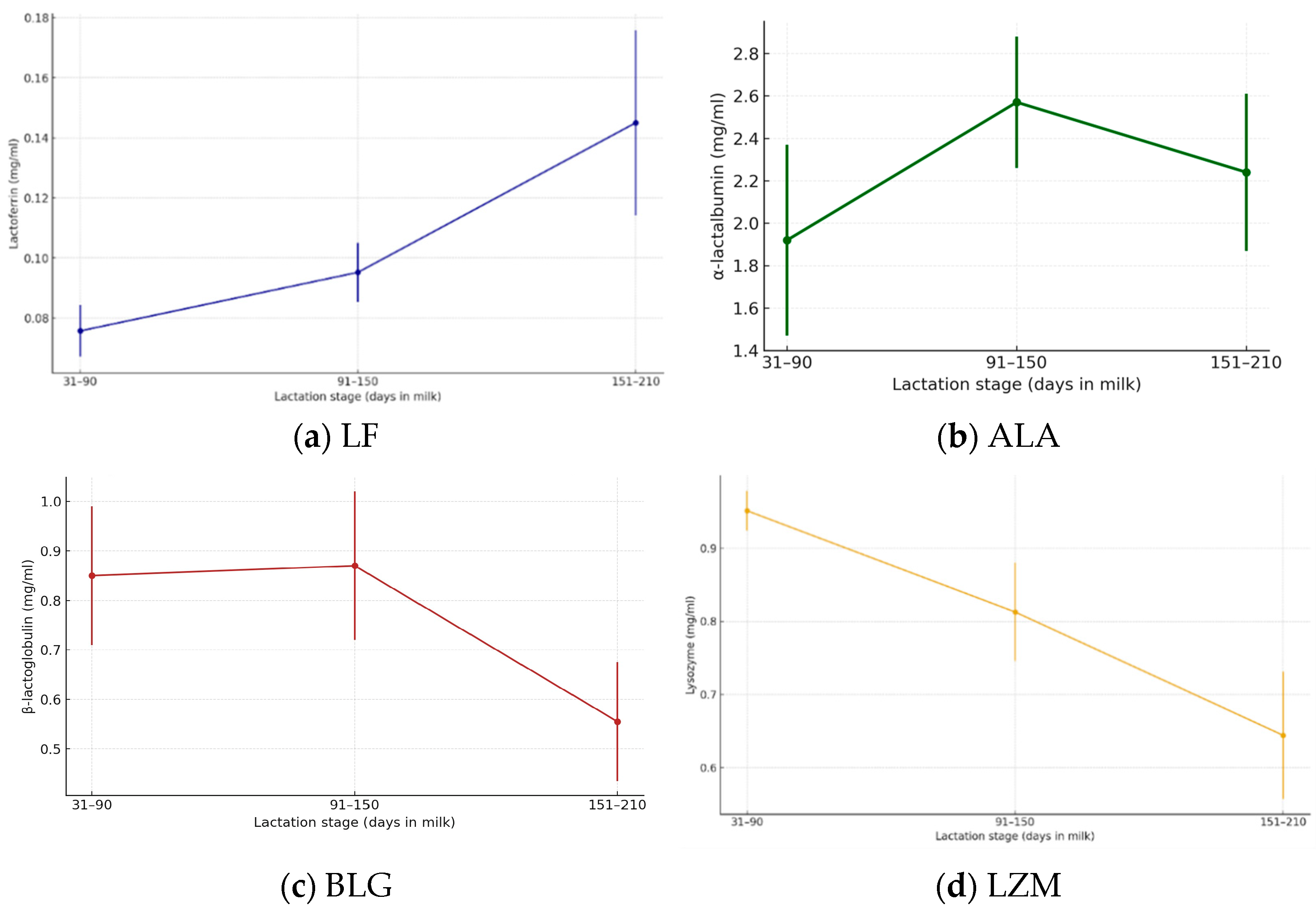

3.2. Bioactive Compounds Across Lactation Stages

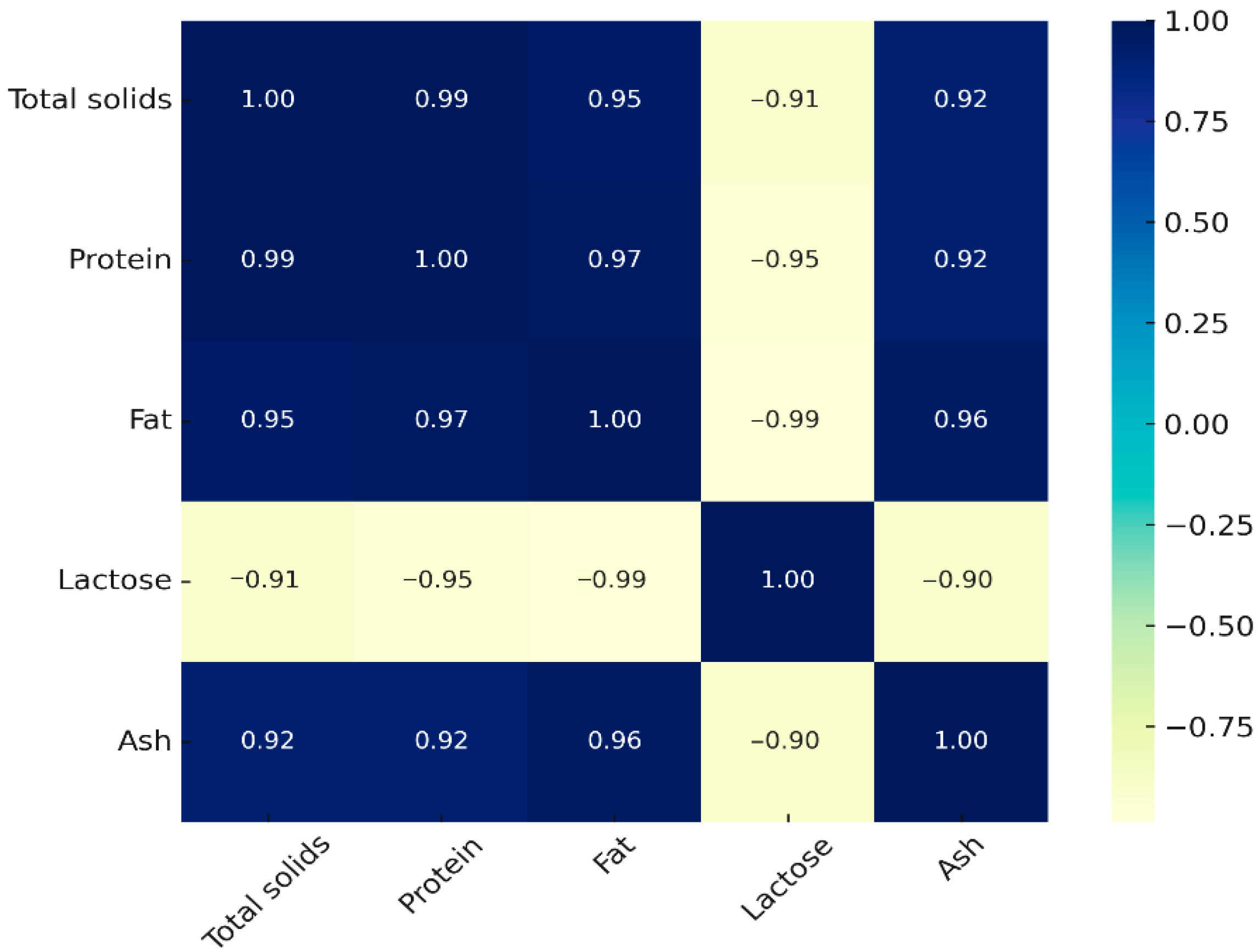

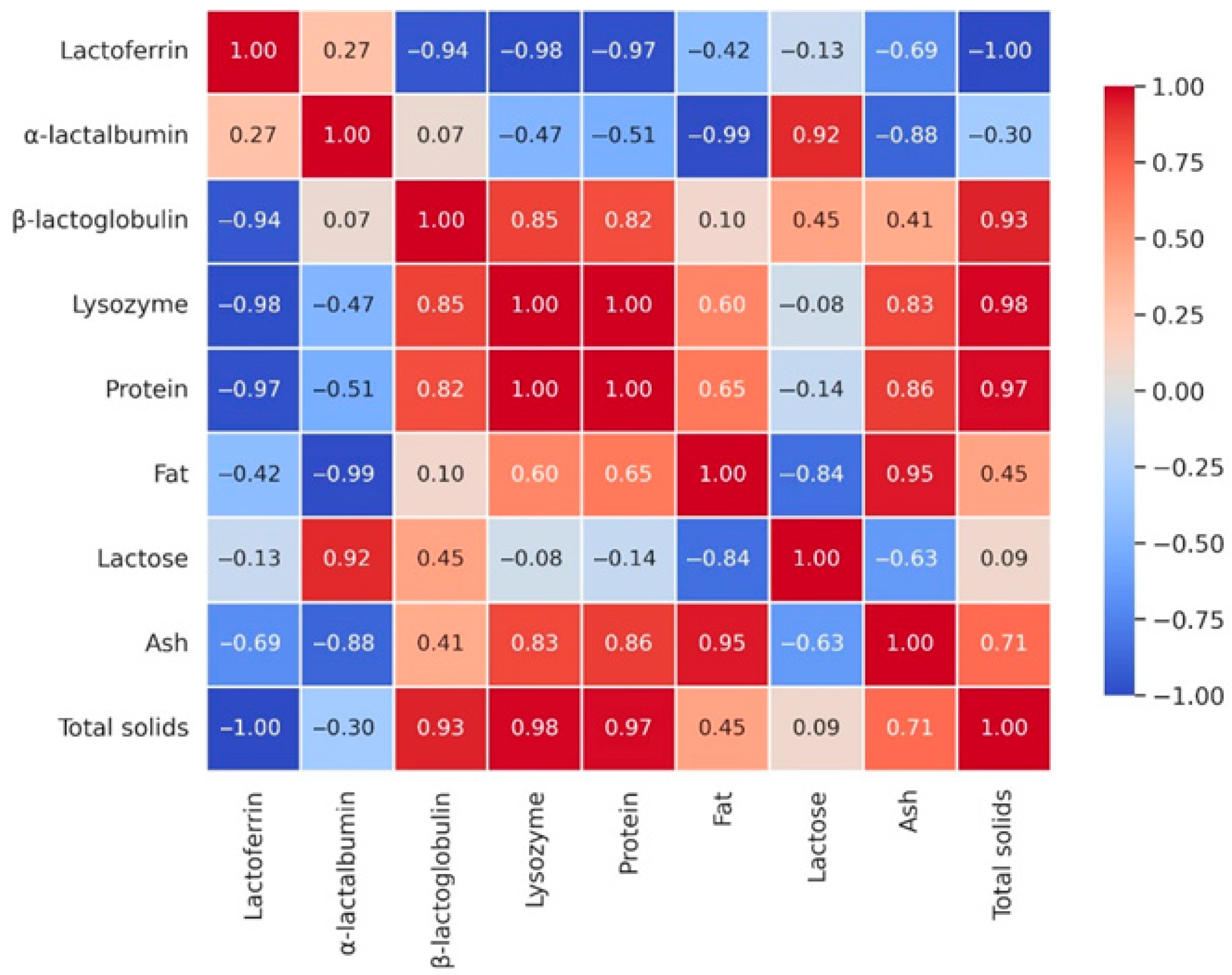

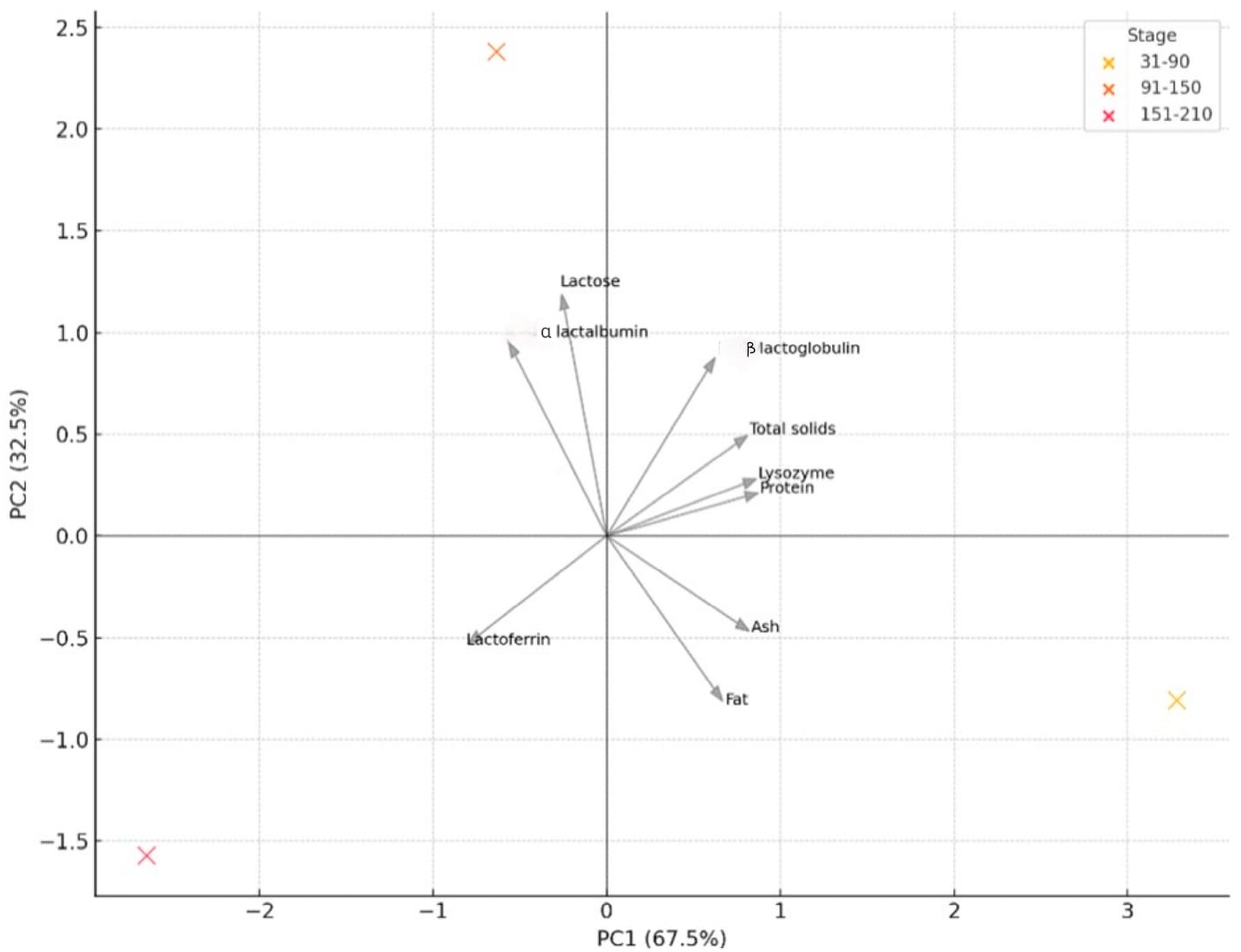

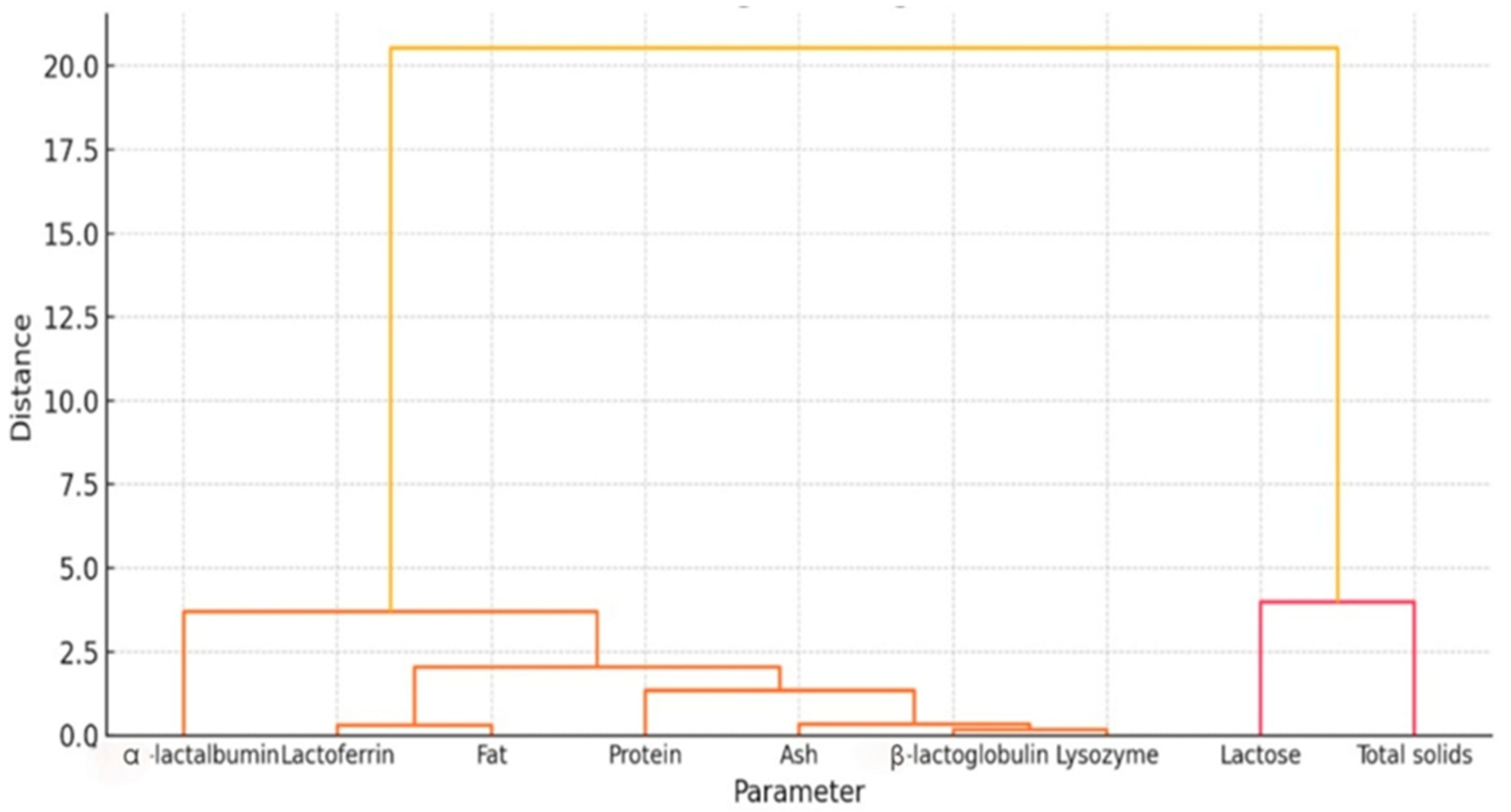

3.3. Multivariate Statistical Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salimei, E.; Fantuz, F. Equid Milk for Human Consumption. Int. Dairy J. 2012, 24, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, M.; Altomonte, I.; Tricò, D.; Lapenta, R.; Salari, F. Current Knowledge on Functionality and Potential Therapeutic Uses of Donkey Milk. Animals 2021, 11, 1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derdak, R.; Sakoui, S.; Pop, O.L.; Muresan, C.I.; Vodnar, D.C.; Addoum, B.; Vulturar, R.; Chis, A.; Suharoschi, R.; Soukri, A.; et al. Insights on Health and Food Applications of Equus Asinus (Donkey) Milk Bioactive Proteins and Peptides—An Overview. Foods 2020, 9, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papademas, P.; Mousikos, P.; Aspri, M. Valorization of Donkey Milk: Technology, Functionality, and Future Prospects. JDS Commun. 2022, 3, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živkov Baloš, M.; Ljubojević Pelić, D.; Jakšić, S.; Lazić, S. Donkey Milk: An Overview of Its Chemical Composition and Main Nutritional Properties or Human Health Benefit Properties. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2023, 121, 104225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Z.; Chen, W.; Li, M.; Ren, W.; Huang, B.; Kou, X.; Ullah, Q.; Wei, L.; Wang, T.; Khan, A.; et al. Is There Sufficient Evidence to Support the Health Benefits of Including Donkey Milk in the Diet? Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1404998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jiang, G.; Ji, C.; Fan, Z.; Ge, S.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Lv, X.; Zhao, F. Comparative Whey Proteome Profiling of Donkey Milk With Human and Cow Milk. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 911454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massouras, T.; Triantaphyllopoulos, K.A.; Theodossiou, I. Chemical Composition, Protein Fraction and Fatty Acid Profile of Donkey Milk during Lactation. Int. Dairy J. 2017, 75, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincenzetti, S.; Santini, G.; Polzonetti, V.; Pucciarelli, S.; Klimanova, Y.; Polidori, P. Vitamins in Human and Donkey Milk: Functional and Nutritional Role. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martemucci, G.; D’Alessandro, A.G. Fat Content, Energy Value and Fatty Acid Profile of Donkey Milk during Lactation and Implications for Human Nutrition. Lipids Health Dis. 2012, 11, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanković, A.; Šubara, G.; Bittante, G.; Šuran, E.; Amalfitano, N.; Aladrović, J.; Kelava Ugarković, N.; Pađen, L.; Pećina, M.; Konjačić, M. Potential of Endangered Local Donkey Breeds in Meat and Milk Production. Animals 2023, 13, 2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertos, I.; López, M.; Jiménez, J.-M.; Cao, M.J.; Corell, A.; Castro-Alija, M.J. Characterisation of Zamorano-Leonese Donkey Milk as an Alternative Sustainably Produced Protein Food. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 872409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correddu, F.; Carta, S.; Mazza, A.; Nudda, A.; Rassu, S.P.G. Effect of Extruded Linseed on Sarda Donkey Milk Quality. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 21, 1200–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumini, D.; Criscione, A.; Bordonaro, S.; Vegarud, G.E.; Marletta, D. Whey Proteins and Their Antimicrobial Properties in Donkey Milk: A Brief Review. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2016, 96, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, M.; Salari, F.; Licitra, R.; La Motta, C.; Altomonte, I. Lysozyme Activity in Donkey Milk. Int. Dairy J. 2019, 96, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturkoglu-Budak, S.; Akal, H.C.; Bereli, N.; Cimen, D.; Akgonullu, S. Use of Antimicrobial Proteins of Donkey Milk as Preservative Agents in Kashar Cheese Production. Int. Dairy J. 2021, 120, 105090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saric, L.; Saric, B.; Kravic, S.; Plavsic, D.; Milovanovic, I.; Gubic, J.; Nedeljkovic, N. Antibacterial Activity of Domestic Balkan Donkey Milk toward Listeria Monocytogenes and Staphylococcus Aureus. Food Feed. Res. 2014, 41, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincenzetti, S.; Pucciarelli, S.; Polzonetti, V.; Polidori, P. Role of Proteins and of Some Bioactive Peptides on the Nutritional Quality of Donkey Milk and Their Impact on Human Health. Beverages 2017, 3, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, A.G.; Martemucci, G.; Jirillo, E.; Leo, V.D. Major Whey Proteins in Donkey’s Milk: Effect of Season and Lactation Stage. Implications for Potential Dietary Interventions in Human Diseases. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2011, 33, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumini, D.; Furlund, C.B.; Comi, I.; Devold, T.G.; Marletta, D.; Vegarud, G.E.; Jonassen, C.M. Antiviral Activity of Donkey Milk Protein Fractions on Echovirus Type 5. Int. Dairy J. 2013, 28, 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yvon, S.; Olier, M.; Leveque, M.; Jard, G.; Tormo, H.; Haimoud-Lekhal, D.A.; Peter, M.; Eutamène, H. Donkey Milk Consumption Exerts Anti-Inflammatory Properties by Normalizing Antimicrobial Peptides Levels in Paneth’s Cells in a Model of Ileitis in Mice. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yvon, S.; Schwebel, L.; Belahcen, L.; Tormo, H.; Peter, M.; Haimoud-Lekhal, D.A.; Eutamene, H.; Jard, G. Effects of Thermized Donkey Milk with Lysozyme Activity on Altered Gut Barrier in Mice Exposed to Water-Avoidance Stress. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 7697–7706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Huang, F.; Du, X.; Wang, C.; Liu, G. Microbial Quality of Donkey Milk during Lactation Stages. Foods 2023, 12, 4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgieva, A.S.; Naydenova, N.; Ivanova, D. Comparative Electrophoretic Analysis Between the Protein Content in Human and Donkey Milk Samples—A Study Covering the Long-Term Lactation Period. Foods 2025, 14, 3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament; Council of the European Union. Directive 2010/63/EU of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. Off. J. Eur. Union 2010, L276, 33–79. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2010/63/oj/eng (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- FAO. Domestic Animal Diversity Information System (DAD-IS). Available online: https://www.fao.org/dad-is/data/en/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- ISO 9622:2013; Milk and Liquid Milk Products—Guidelines for the Application of Mid-Infrared Spectrometry. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/56874.html (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Kasapidou, E.; Stergioudi, R.-A.; Papadopoulos, V.; Mitlianga, P.; Papatzimos, G.; Karatzia, M.-A.; Amanatidis, M.; Tortoka, V.; Tsiftsi, E.; Aggou, A.; et al. Effect of Farming System and Season on Proximate Composition, Fatty Acid Profile, Antioxidant Activity, and Physicochemical Properties of Retail Cow Milk. Animals 2023, 13, 3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polidori, P.; Vincenzetti, S. Effects of Thermal Treatments on Donkey Milk Nutritional Characteristics. Recent Pat. Food. Nutr. Agric. 2013, 5, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummins, C.; Berry, D.P.; Murphy, J.P.; Lorenz, I.; Kennedy, E. The Effect of Colostrum Storage Conditions on Dairy Heifer Calf Serum Immunoglobulin G Concentration and Preweaning Health and Growth Rate. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 525–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.Y.; Pang, K.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhao, L.; Chen, S.W.; Dong, M.L.; Ren, F.Z. Composition, Physiochemical Properties, Nitrogen Fraction Distribution, and Amino Acid Profile of Donkey Milk. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 1635–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malacarne, M.; Criscione, A.; Franceschi, P.; Bordonaro, S.; Formaggioni, P.; Marletta, D.; Summer, A. New Insights into Chemical and Mineral Composition of Donkey Milk throughout Nine Months of Lactation. Animals 2019, 9, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, I.C.B.; Rangel, A.H.D.N.; Ribeiro, C.V.D.M.; Oliveira, C.A.d.A. Donkey Milk Composition Is Altered by Lactation Stage and Jennies Age. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 115, 104971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantuz, F.; Ferraro, S.; Todini, L.; Piloni, R.; Mariani, P.; Salimei, E. Donkey Milk Concentration of Calcium, Phosphorus, Potassium, Sodium and Magnesium. Int. Dairy J. 2012, 24, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, S.; Meena, G.S.; Gautam, P.B.; Rai, D.C.; Kumari, S. A Comprehensive Review on Donkey Milk and Its Products: Composition, Functionality and Processing Aspects. Food Chem. Adv. 2024, 4, 100647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, M.; Altomonte, I.; Licitra, R.; Salari, F. Nutritional and Nutraceutical Quality of Donkey Milk. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2018, 65, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivkov-Balos, M.; Popov, N.; Vidakovic-Knezevic, S.; Savic, S.; Gajdov, V.; Jaksic, S.; Ljubojevic-Pelic, D. Nutritional Quality of Donkey Milk during the Lactation. Bio. Anim. Husb. 2024, 40, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspri, M.; Souroullas, K.; Ioannou, C.; Papademas, P. Physico-Chemical Composition and Antimicrobial Protein Content of Early Lactation Donkey Milk. Int. J. Food. Stud. 2019, 8, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, A.; Coroian, A.; Coroian, C.O. Donkey Milk Is an Appreciated Food Due to Its Benefits It Brings to the Human Body. In Proceedings of the ABAH BIOFLUX Animal Biology & Animal Husbandry; ABAH BIOFLUX, Bikaner, India, 1 January 2015; Volume 7, pp. 86–91. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, A.-L.; Gordon, A.W.; Hamill, G.; Ferris, C.P. Milk Composition and Production Efficiency within Feed-To-Yield Systems on Commercial Dairy Farms in Northern Ireland. Animals 2022, 12, 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Wei, L.; Chen, X.; Zhu, H.; Wei, J.; Zhu, M.; Khan, M.Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Z. Nutritional Composition and Biological Activities of Donkey Milk: A Narrative Review. Foods 2025, 14, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunsolo, V.; Saletti, R.; Muccilli, V.; Gallina, S.; Di Francesco, A.; Foti, S. Proteins and Bioactive Peptides from Donkey Milk: The Molecular Basis for Its Reduced Allergenic Properties. Food Res. Int. 2017, 99, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayak, C.M.; Ramachandra, C.T.; Nidoni, U.; Hiregoudar, S.; Ram, J.; Naik, N. Physico-Chemical Composition, Minerals, Vitamins, Amino Acids, Fatty Acid Profile and Sensory Evaluation of Donkey Milk from Indian Small Grey Breed. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 2967–2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messias, T.B.O.N.; Sant’Ana, A.M.S.; Araújo, E.O.M.; Rangel, A.H.N.; Vasconcelos, A.S.E.; Salles, H.O.; Morgano, M.A.; Silva, V.S.N.; Pacheco, M.T.B.; Queiroga, R.C.R.E. Milk from Nordestina Donkey Breed in Brazil: Nutritional Potential and Physicochemical Characteristics in Lactation. Int. Dairy J. 2022, 127, 105291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Zhao, L.; Zheng, Q.; Dong, M.L.; Chu, Y.; Ren, F.Z. Analysis of Chemical Composition and Microbial Index of Xinjiang Jiangyue Donkey Milk. FOOD Sci. 2008, 29, 303. [Google Scholar]

- Garhwal, R.; Sangwan, K.; Mehra, R.; Bhardwaj, A.; Pal, Y.; Nayan, V.; Legha, R.A.; Tiwari, M.; Chauhan, M.S.; Iquebal, M.A.; et al. Comparative Metabolomics Analysis of Halari Donkey Colostrum and Mature Milk throughout Lactation Stages Using 1H Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. LWT 2023, 182, 114805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, X.; Guo, H. The Nutritional Ingredients and Antioxidant Activity of Donkey Milk and Donkey Milk Powder. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2018, 27, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markus, C.R.; Olivier, B.; de Haan, E.H.F. Whey Protein Rich in Alpha-Lactalbumin Increases the Ratio of Plasma Tryptophan to the Sum of the Other Large Neutral Amino Acids and Improves Cognitive Performance in Stress-Vulnerable Subjects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 75, 1051–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Pei, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhou, J.; Gong, Y.; You, J.; Cao, Y.; Chen, J.; Cai, Y.; et al. Lactoferrin Prevents Heat Stroke-Induced Intestinal Barrier Damage by Reducing Ferroptosis via Regulating MAPK Signaling Pathway: In Vitro and In Vivo Studies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 319, 145454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legrand, D. Overview of Lactoferrin as a Natural Immune Modulator. J. Pediatr. 2016, 173, S10–S15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lönnerdal, B. Bioactive Proteins in Human Milk: Health, Nutrition, and Implications for Infant Formulas. J. Pediatr. 2016, 173, S4–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layman, D.K.; Lönnerdal, B.; Fernstrom, J.D. Applications for α-Lactalbumin in Human Nutrition. Nutr. Rev. 2018, 76, 444–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, C.R.; Jonkman, L.M.; Lammers, J.H.C.M.; Deutz, N.E.P.; Messer, M.H.; Rigtering, N. Evening Intake of Alpha-Lactalbumin Increases Plasma Tryptophan Availability and Improves Morning Alertness and Brain Measures of Attention. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 1026–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Expósito, I.; Recio, I. Protective Effect of Milk Peptides: Antibacterial and Antitumor Properties. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2008, 606, 271–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madureira, A.R.; Pereira, C.I.; Gomes, A.M.P.; Pintado, M.E.; Xavier Malcata, F. Bovine Whey Proteins—Overview on Their Main Biological Properties. Food Res. Int. 2007, 40, 1197–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legrand, D.; Elass, E.; Carpentier, M.; Mazurier, J. Lactoferrin: A Modulator of Immune and Inflammatory Responses. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2005, 62, 2549–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincenzetti, S.; Polidori, P.; Mariani, P.; Cammertoni, N.; Fantuz, F.; Vita, A. Donkey’s Milk Protein Fractions Characterization. Food Chem. 2008, 106, 640–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubić, J.; Milovanović, I.; Iličić, M.; Tomić, J.; Torbica, A.; Šarić, L.; Ilić, N. Comparison of the Protein and Fatty Acid Fraction of Balkan Donkey and Human Milk. Mljekarstvo Dairy Experts J. 2015, 65, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubić, J.; Tasić, T.; Tomić, J.; Torbica, A. Determination of whey proteins profile in Balkan donkey’s milk during lactation period. J. Hyg. Eng. Des. 2014, 8, 178–180. [Google Scholar]

- Pastuszka, R.; Barłowska, J.; Litwińczuk, Z. Allergenicity of Milk of Different Animal Species in Relation to Human Milk. Postepy Hig. Med. Dosw (Online) 2016, 70, 1451–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasmina, G.; Jelena, T.; Aleksandra, T.; Mirela, I.; Tatjana, T.; Ljubiša, Š.; Sanja, P. Characterization of Several Milk Proteins in Domestic Balkan Donkey Breed during Lactation, Using Lab-on-a-Chip Capillary Electrophoresis. Chem. Ind. Chem. Eng. Q. 2016, 22, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, V.M.; Schadt, I.; La Terra, S.; Caccamo, M.; Caggia, C. Lysozyme Sources for Disease Prevention and Health Promotion—Donkey Milk in Alternative to Hen Egg-White Lysozyme. Future Foods 2024, 9, 100321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Stage 31–90 | Stage 91–150 | Stage 151–210 | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Min–Max | Mean ± SD | Min–Max | Mean ± SD | Min–Max | ||

| Lactoferrin | 0.0757 ± 0.0085 | 0.0598–0.0918 | 0.0951 ± 0.0098 | 0.0797–0.1087 | 0.1449 ± 0.0308 | 0.0801–0.1986 | <0.001 |

| α-lactalbumin | 1.9169 ± 0.4541 | 1.1495–2.6298 | 2.5856 ± 0.3286 | 1.9768–3.1294 | 2.2512 ± 0.3091 | 1.8203–2.8015 | <0.001 |

| β-lactoglobulin | 0.8441 ± 0.1402 | 0.5510–0.9945 | 0.8671 ± 0.1634 | 0.6110–1.1785 | 0.5554 ± 0.0988 | 0.4145–0.7460 | <0.001 |

| Lysozyme | 0.9513 ± 0.0270 | 0.9087–0.9881 | 0.8127 ± 0.0673 | 0.7016–0.9098 | 0.6440 ± 0.0869 | 0.5204–0.8272 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Plotuna, A.-M.; Hotea, I.; Ban-Cucerzan, A.; Imre, K.; Herman, V.; Nichita, I.; Popa, I.; Tîrziu, E. Bioactive Protein Profile and Compositional Evolution of Donkey Milk Across Lactation Reflecting Its Nutritional and Functional Food Value. Foods 2025, 14, 4284. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244284

Plotuna A-M, Hotea I, Ban-Cucerzan A, Imre K, Herman V, Nichita I, Popa I, Tîrziu E. Bioactive Protein Profile and Compositional Evolution of Donkey Milk Across Lactation Reflecting Its Nutritional and Functional Food Value. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4284. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244284

Chicago/Turabian StylePlotuna, Ana-Maria, Ionela Hotea, Alexandra Ban-Cucerzan, Kalman Imre, Viorel Herman, Ileana Nichita, Ionela Popa, and Emil Tîrziu. 2025. "Bioactive Protein Profile and Compositional Evolution of Donkey Milk Across Lactation Reflecting Its Nutritional and Functional Food Value" Foods 14, no. 24: 4284. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244284

APA StylePlotuna, A.-M., Hotea, I., Ban-Cucerzan, A., Imre, K., Herman, V., Nichita, I., Popa, I., & Tîrziu, E. (2025). Bioactive Protein Profile and Compositional Evolution of Donkey Milk Across Lactation Reflecting Its Nutritional and Functional Food Value. Foods, 14(24), 4284. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244284