Phytochemical Profiles, In Vitro Antioxidants and Antihypertensive Properties of Wild Blueberries (Vaccinium angustifolium)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Standard Preparation

Sample Extraction

Preparation of Blueberry Extract

Characterization of Blueberry Extracts by LC/MS Analysis

DPPH (2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) Radical Scavenging Assay Blueberry Polyphenolic Extracts

Determination of Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

Determination of Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

ACE-Inhibitory Activity of Blueberry Polyphenolic Extracts

Statistical Analyses

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Phytochemical Profile

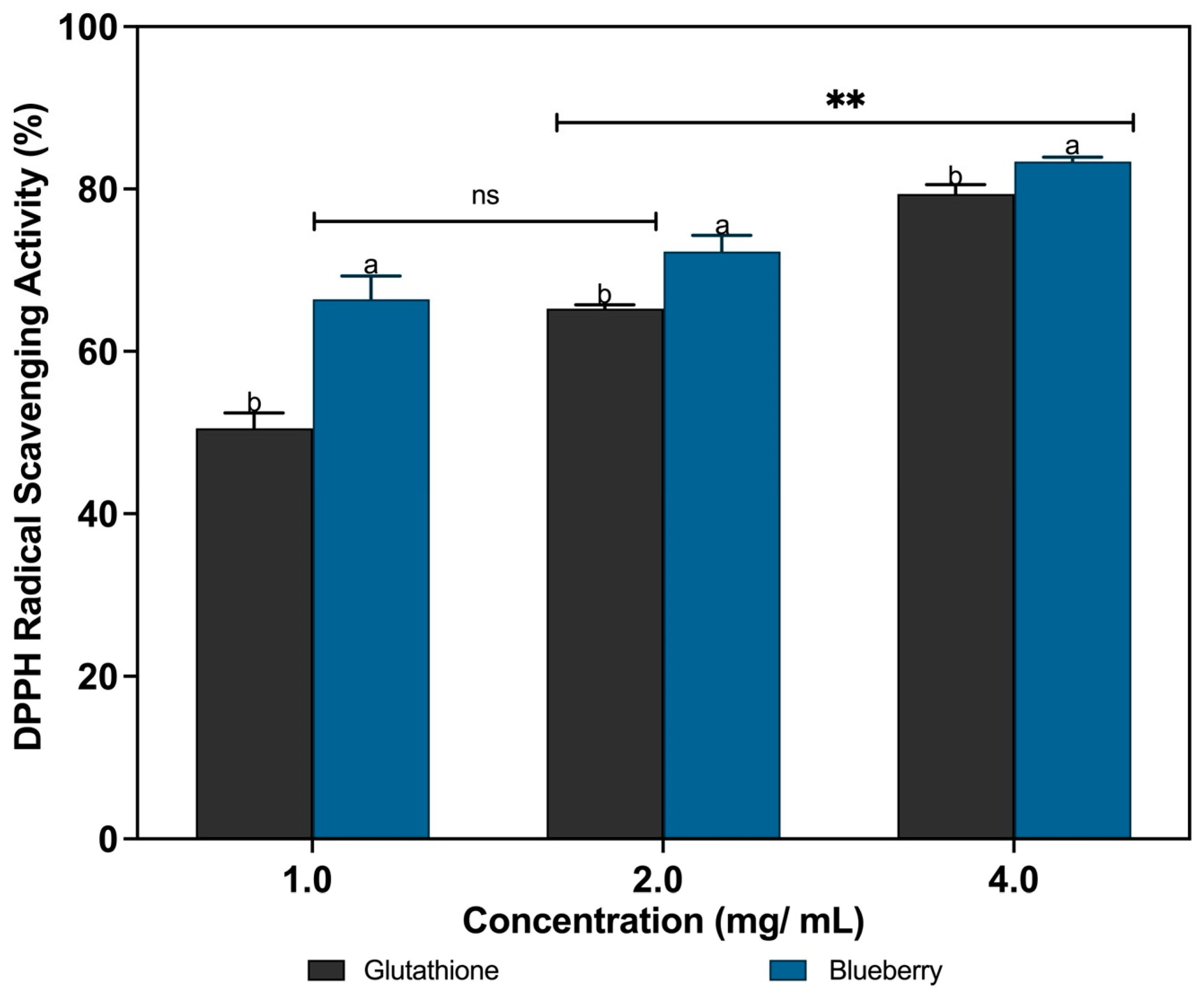

3.2. DPPH Radical Scavenging Activities

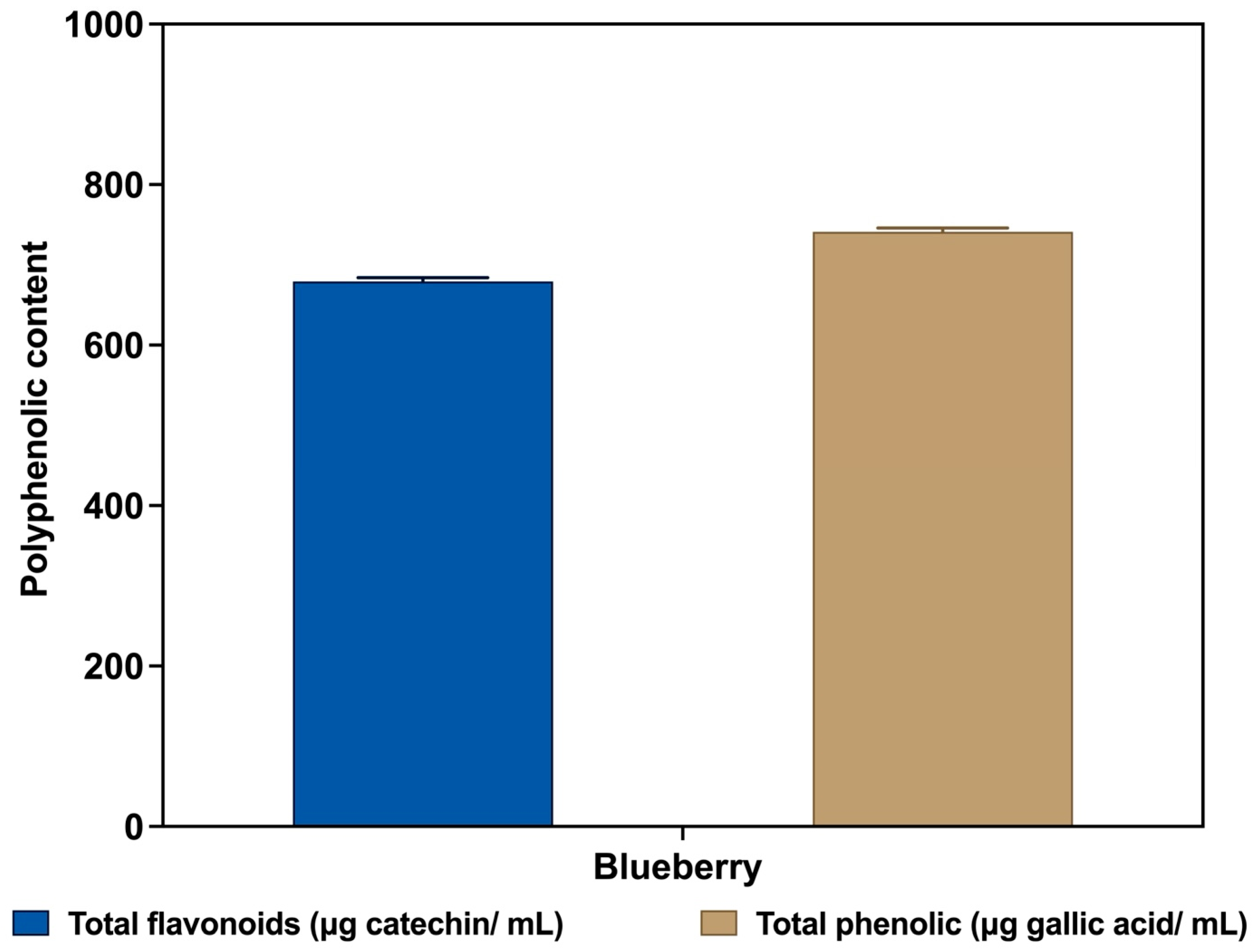

3.3. The Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

3.4. The Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

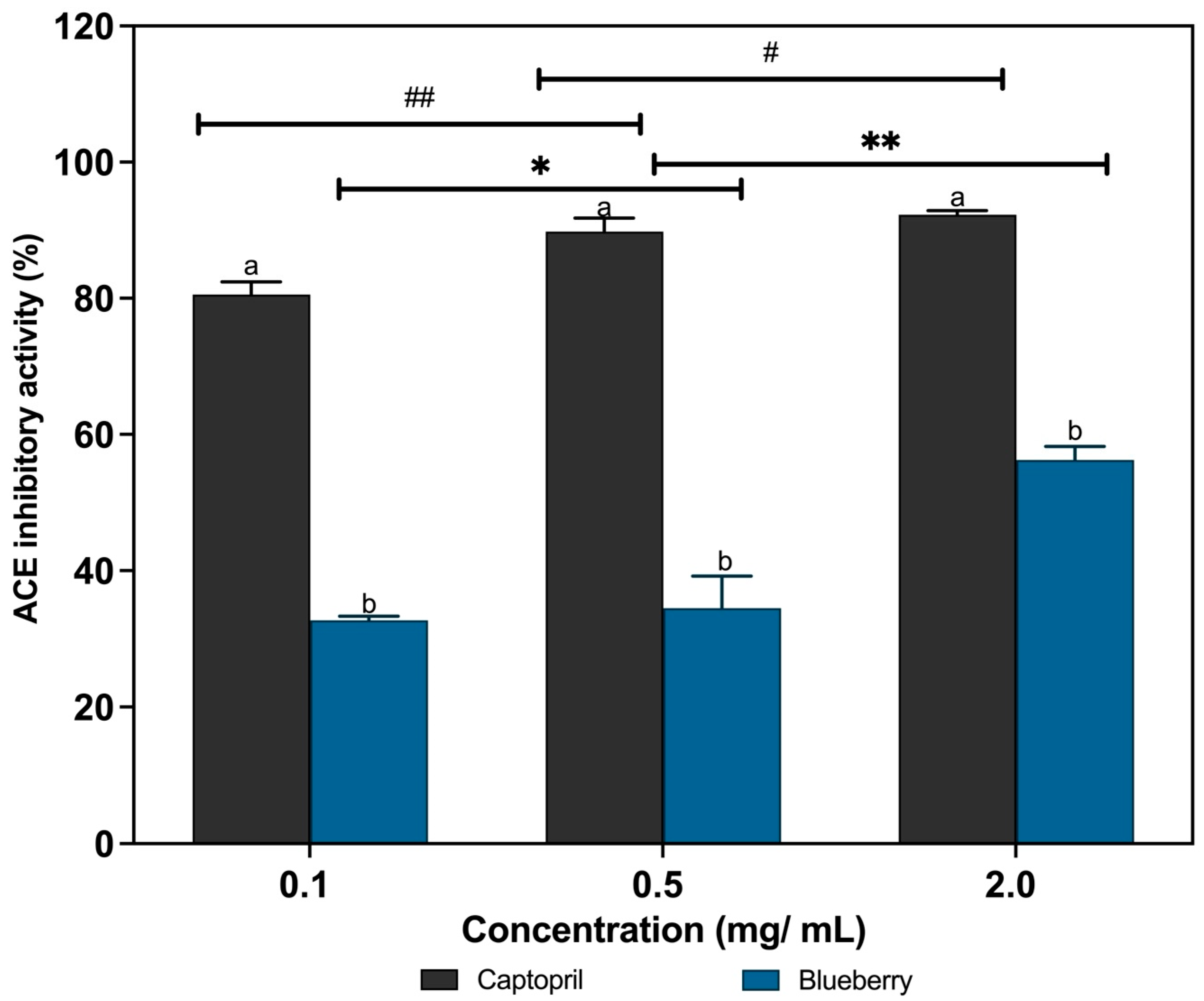

3.5. In Vitro ACE-Inhibitory Activity

3.6. Conclusions

3.7. Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GAE | Gallic acid equivalents |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RNS | Reactive nitrogen species |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay |

| HPLC | High-performance liquid chromatography |

| ACE | Angiotensin-II converting enzyme |

| ACNs | Anthocyanins |

| H-ESI | Electrospray ionization |

| UPLC | Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography |

| DPPH | 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| DRSA | DPPH radical scavenging activity |

| TFC | total flavonoids content |

| FAPGG | N-[3-(2-furyl) acryloyl]-Phe_Gly_Gly, 98% |

| LCMS | Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry |

References

- Sławińska, N.; Prochoń, K.; Olas, B. A review on berry seeds—A special Emphasis on their chemical content and health-promoting properties. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baby, B.; Antony, P.; Vijayan, R. Antioxidant and anticancer properties of berries. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 58, 2491–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Thomas-Ahner, J.M.; Riedl, K.M.; Bailey, M.T.; Vodovotz, Y.; Schwartz, S.J.; Clinton, S.K. Dietary black raspberries impact the colonic microbiome and phytochemical metabolites in mice. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2019, 63, 1800636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorzi, M.; Gai, F.; Medana, C.; Aigotti, R.; Morello, S.; Peiretti, P.G. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacity of small berries. Food 2020, 9, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrovankova, S.; Sumczynski, D.; Mlcek, J.; Jurikova, T.; Sochor, J. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity in different types of berries. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 24673–24706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, K.P.; Vorsa, N.; Natarajan, P.; Elavarthi, S.; Iorizzo, M.; Reddy, U.K.; Melmaiee, K. Admixture analysis using genotyping-by-sequencing reveals genetic relatedness and parental lineage distribution in highbush blueberry genotypes and cross derivatives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, L.; Cang, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, R.; Fan, R. The research progress of extraction, purification and analysis methods of phenolic compounds from blueberry: A comprehensive review. Molecules 2023, 28, 3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalska, A.; Łysiak, G. Bioactive compounds of blueberries: Post-harvest factors influencing the nutritional value of products. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 18642–18663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Sun, Z.; Zeng, Y.; Luo, M.; Yang, J. Molecular mechanism and health role of functional ingredients in blueberry for chronic disease in human beings. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrhovsek, U.; Masuero, D.; Palmieri, L.; Mattivi, F. Identification and quantification of flavonol glycosides in cultivated blueberry cultivars. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2012, 25, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.Y.; Chen, H.; Camp, M.J.; Ehlenfeldt, M.K. Flavonoid constituents and their contribution to antioxidant activity in cultivars and hybrids of rabbiteye blueberry (Vaccinium ashei Reade). Food Chem. 2012, 132, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, M.; Whitney, K. Examination of Primary and Secondary Metabolites Associated with a Plant-Based Diet and Their Impact on Human Health. Foods 2024, 13, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunea, A.; Rugină, D.; Sconţa, Z.; Pop, R.M.; Pintea, A.; Socaciu, C.; Tăbăran, F.; Grootaert, C.; Struijs, K.; VanCamp, J. Anthocyanin determination in blueberry extracts from various cultivars and their antiproliferative and apoptotic properties in B16-F10 metastatic murine melanoma cells. Phytochemistry 2013, 95, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, S.W.; Tomlinson, B. Effects of bilberry supplementation on metabolic and cardiovascular disease risk. Molecules 2020, 25, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.K.; Cheung, S.C.; Lau, R.A.; Benzie, I.F. Bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.). Herb. Med. 2011, 5386, 55–71. [Google Scholar]

- Rashwan, A.K.; Osman, A.I.; Karim, N.; Mo, J.; Chen, W. Unveiling the mechanisms of the Development of blueberries-based Functional foods: An updated and Comprehensive Review. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 40, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tan, D.; Shi, L.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tong, C.; Hou, M. Blueberry anthocyanins-enriched extracts attenuate cyclophosphamide-induced cardiac injury. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Guo, Y.; Liu, M.; Chen, X.; Xiao, X.; Wang, S.; Chen, F. Structure and function of blueberry anthocyanins: A review of recent advances. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 88, 104864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ockermann, P.; Headley, L.; Lizio, R.; Hansmann, J. A review of the properties of anthocy1anins and their influence on factors affecting cardiometabolic and cognitive health. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.C.; Nunes, A.R.; Falcão, A.; Alves, G.; Silva, L.R. Dietary effects of anthocyanins in human health: A comprehensive review. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Ling, W.; Du, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, D.; Deng, S.; Yang, L. Effects of anthocyanins on cardiometabolic health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Adv. Nutr. 2017, 8, 684–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, J.S.; Nguyen, H.P.; Shen, S.; Schug, K.A. General method for extraction of blueberry anthocyanins and identification using high performance liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization-ion trap-time of flight-mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2009, 1216, 4728–4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewanto, V.; Wu, X.; Adom, K.K.; Liu, R.H. Thermal processing enhances the nutritional value of tomatoes by increasing total antioxidant activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 3010–3014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatipoğlu, G.; Sökmen, M.; Bektaş, E.; Daferera, D.; Sökmen, A.; Demir, E.; Şahin, H. Automated and standard extraction of antioxidant phenolic compounds of Hyssopus officinalis L. ssp. angustifolius. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 43, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.M.; Nahar, L.; Mannan, A.; Ul-Haq, I.; Arfan, M.; Ali Khan, G.; Sarker, S.D. Cytotoxicity, in vitro anti-leishmanial and fingerprint HPLC-photodiode array analysis of the roots of Trillium govanianum. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 32, 2193–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekacar, S.; Deliorman Orhan, D. Investigation of antidiabetic effect of Pistacia atlantica leaves by activity-guided fractionation and phytochemical content analysis byLC-QTOF-MS. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 826261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Arroyo, S.; Barrajón-Catalán, E.; Micol, V.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. High-performance liquid chromatography with diode array detection coupled to electrospray time-of-flight and ion-trap tandem mass spectrometry to identify phenolic compounds from a Cistus ladanifer aqueous extract. Phytochem. Anal. 2010, 21, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gülçin, I.; Elmastaş, M.; Aboul-Enein, H.Y. Determination of antioxidant and radical scavenging activity of Basil (Ocimum basilicum L. Family Lamiaceae) assayed by different methodologies. Phytother. Res. Int. J. Devoted Pharmacol. Toxicol. Eval. Nat. Prod. Deriv. 2007, 21, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singleton, V.L.; Orthofer, R.; Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. [14] Analysis of total phenols and other oxidation substrates and antioxidants by means of folin-ciocalteu reagent. In Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999; Volume 299, pp. 152–178. [Google Scholar]

- Zhishen, J.; Mengcheng, T.; Jianming, W. The determination of flavonoid contents in mulberry and their scavenging effects on superoxide radicals. Food Chem. 1999, 64, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udenigwe, C.C.; Lin, Y.S.; Hou, W.C.; Aluko, R.E. Kinetics of the inhibition of renin and angiotensin I-converting enzyme by flaxseed protein hydrolysate fractions. J. Funct. Foods 2009, 1, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdu, C.F.; Gatto, J.; Freuze, I.; Richomme, P.; Laurens, F.; Guilet, D. Comparison of two methods, UHPLC-UV and UHPLC-MS/MS, for the quantification of polyphenols in cider apple juices. Molecules 2013, 18, 10213–10227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Kim, H.W.; Lee, M.K.; Lee, S.H.; Jang, H.H.; Hwang, Y.J.; Kim, J.B. Comparison of flavonoid characteristics between blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) and black raspberry (Rubus coreanus) cultivated in Korea using UPLC-DAD-QTOF/MS. Korean J. Environ. Agric. 2017, 36, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Hu, J.; Hu, D.; Yang, X. A role of gallic acid in oxidative damage diseases: A comprehensive review. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2019, 14, 1934578X19874174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keivani, N.; Piccolo, V.; Marzocchi, A.; Maisto, M.; Tenore, G.C.; Summa, V. Optimization and validation of procyanidins extraction and phytochemical profiling of seven herbal matrices of nutraceutical interest. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.W.; Han, H.A.; Kim, J.K.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, M.K. Comparison of phytochemicals and antioxidant activities of berries cultivated in Korea: Identification of phenolic compounds in Aronia by HPLC/Q-TOF MS. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2021, 26, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cásedas, G.; González-Burgos, E.; Smith, C.; López, V.; Gómez-Serranillos, M.P. Regulation of redox status in neuronal SH-SY5Y cells by blueberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.) juice, cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon A.) juice and cyanidin. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 118, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.L.; Liao, X.J.; Wang, Y.H.; Si, X.; Shu, C.; Gong, E.S.; Xie, X.; Ran, X.-L.; Li, B. Identification of cyanidin-3-arabinoside extracted from blueberry as a selective protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibitor. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 13624–13634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; McKinnie, S.M.; Farhan, M.; Paul, M.; McDonald, T.; McLean, B.; Oudit, G.Y. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 metabolizes and partially inactivates pyr-apelin-13 and apelin-17: Physiological effects in the cardiovascular system. Hypertension 2016, 68, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guo, X.; Hu, X.; Li, T.; Fu, X.; Liu, R.H. Comparison of phytochemical profiles, antioxidant and cellular antioxidant activities of different varieties of blueberry (Vaccinium spp.). Food Chem. 2017, 217, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dong, W.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Y. Identification and Analysis of Phenolic Compounds in Vaccinium uliginosum L. and Its Lipid-Lowering Activity in Vitro. Foods 2024, 13, 3438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachowicz-Wiśniewska, S.; Pratap-Singh, A.; Ochmian, I.; Kapusta, I.; Kotowska, A.; Pluta, S. Biodiversity in nutrients and biological activities of 14 highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum L.) cultivars. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 22063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okan, O.T.; Deniz, I.; Yayli, N.; Sat, I.G.; Oz, M.; Hatipoglu Serdar, G. Antioxidant activity, sugar content and phenolic profiling of blueberries cultivars: A comprehensive comparison. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2018, 46, 639–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, G.; Degeneve, A.; Mullen, W.; Crozier, A. Identification of flavonoid and phenolic antioxidants in black currants, blueberries, raspberries, red currants, and cranberries. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 3901–3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaconeasa, Z.; Iuhas, C.I.; Ayvaz, H.; Rugină, D.; Stanilă, A.; Dulf, F.; Pintea, A. Phytochemical characterization of commercial processed blueberry, blackberry, blackcurrant, cranberry and raspberry and their antioxidant activity. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, X.; Huang, L. Correlation between antioxidant activities and phenolic contents of radix Angelicae sinensis (Danggui). Molecules 2009, 14, 5349–5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamdar, S.N.; Rajalakshmi, V.; Sharma, A. Antioxidant and ace inhibitory properties of poultry viscera protein hydrolysate and its peptide fractions. J. Food Biochem. 2012, 36, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackelford, L.; Mentreddy, S.R.; Cedric, S. Determination of total phenolics, flavonoids and antioxidants and chemopreventive potential of basil (Ocimum basilicum L. and Ocimum tenuiflorum L.). Int. J. Cancer Res. 2009, 5, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, P.; Maier, C. In vitro antioxidant activities and polyphenol contents of seven commercially available fruits. Pharmacogn. Res. 2016, 8, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, R. Antioxidant and enzyme-inhibitory activities of water-soluble extracts from Bangladesh vegetables. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 45, e13417. [Google Scholar]

- Olarewaju, O.A.; Alashi, A.M.; Taiwo, K.A.; Oyedele, D.; Adebooye, O.C.; Aluko, R.E. Influence of nitrogen fertilizer micro-dosing on phenolic content, antioxidant, and anticholinesterase properties of aqueous extracts of three tropical leafy vegetables. J. Food Biochem. 2018, 42, e12566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quideau, S.; Deffieux, D.; Douat-Casassus, C.; Pouységu, L. Plant polyphenols: Chemical properties, biological activities, and synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 586–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovanelli, G.; Buratti, S. Comparison of polyphenolic composition and antioxidant activity of wild Italian blueberries and some cultivated varieties. Food Chemistry 2009, 112, 903–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hera, O.; Sturzeanu, M.; Vîjan, L.E.; Tudor, V.; Teodorescu, R. Biochemical Evaluation of Some Fruit Characteristics of Blueberry Progenies Obtained from ‘Simultan × Duke’. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 18603–18616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunea, A.; Rugina, O.D.; Pintea, A.M.; Sconta, Z.; Bunea, C.I.; Socaciu, C. Comparative polyphenolic content and antioxidant activities of some wild and cultivated blueberries from Romania. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2011, 39, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Finn, C.E.; Wrolstad, R.E. Comparison of anthocyanin pigment and other phenolic compounds of Vaccinium membranaceum and Vaccinium ovatum native to the Pacific Northwest of North America. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 7039–7044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalt, W.; Ryan, D.A.; Duy, J.C.; Prior, R.L.; Ehlenfeldt, M.K.; Vander Kloet, S.P. Interspecific variation in anthocyanins, phenolics, and antioxidant capacity among genotypes of highbush and lowbush blueberries (Vaccinium section cyanococcus spp.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001, 49, 4761–4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jimenez-Garcia, S.N.; Guevara-Gonzalez, R.G.; Miranda-Lopez, R.; Feregrino-Perez, A.A.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; Vazquez-Cruz, M.A. Functional properties and quality characteristics of bioactive compounds in berries: Biochemistry, biotechnology, and genomics. Food Res. Int. 2013, 54, 1195–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Ma, X.; Cai, T.; Li, Y. Flavonoid intake, inflammation, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in US adults: A cross-sectional study. Nutr. Metab. 2025, 22, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knekt, P.; Kumpulainen, J.; Järvinen, R.; Rissanen, H.; Heliövaara, M.; Reunanen, A.; Hakulinen, T.; Aromaa, A. Flavonoid intake and risk of chronic diseases. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 76, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazidi, M.; Katsiki, N.; Banach, M. A greater flavonoid intake is associated with lower total and cause-specific mortality: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, M.L.; Peterson, J.J.; Patel, R.; Jacques, P.F.; Shah, R.; Dwyer, J.T. Flavonoid intake and cardiovascular disease mortality in a prospective cohort of US adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskaya-Dikmen, C.; Yucetepe, A.; Karbancioglu-Guler, F.; Daskaya, H.; Ozcelik, B. Angiotensin-I-converting enzyme (ACE)-inhibitory peptides from plants. Nutrients 2017, 9, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.; Anuar, T.A.F.T.; Suffian, I.F.M.; Hamid, A.A.; Omar, M.N.; Mustafa, B.E.; Ahmad, W.W. Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibition Activity by Syzygium polyanthum Wight (Walp.) Leaves: Mechanism and Specificity. Pharmacogn. J. 2022, 14, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olagunju, A.I.; Omoba, O.S.; Enujiugha, V.N.; Alashi, A.M.; Aluko, R.E. Antioxidant properties, ACE/renin inhibitory activities of pigeon pea hydrolysates and effects on systolic blood pressure of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 1879–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, K.R.; Sturrock, E.D.; Riordan, J.F.; Ehlers, M.R. Ace revisited: A new target for structure-based drug design. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003, 2, 891–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darwish, M.M.; Ibrahim, R.S.; Metwally, A.M.; Mahrous, R.S. In-depth in silico and in vitro screening of selected edible plants for identification of selective C-domain ACE-1 inhibitor and its synergistic effect with captopril. Food Biosci. 2024, 59, 104115. [Google Scholar]

- Alashi, A.M.; Taiwo, K.A.; Oyedele, D.; Adebooye, O.C.; Aluko, R.E. Antihypertensive properties of aqueous extracts of vegetable leaf-fortified bread after oral administration to spontaneously hypertensive rats. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 53, 1705–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Polyphenolic/Bioactive Compounds | Molecular Formula | Actual Retention Time (min) | m/z (Da) | MS/MS (Da) | Concentration (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin C | C6H8O6 | 1.1 | 175.0239– 175.0257 | 70.0000– 700.0000 | 1.655 |

| Cyanidin | C15H11O6+ | 8.8 | 287.0536– 287.0564 | 70.0000– 700.0000 | 0.795 |

| Quercetin | C15H10O7 | 9.2 | 303.0484– 303.0514 | 70.0000– 700.0000 | 0.283 |

| Gallic Acid | C7H6O5 | 2.4 | 169.0135– 169.0151 | 70.0000– 700.0000 | 2.172 |

| Procyanidin B2 | C30H26O12 | 8.7 | 577.1323– 577.1381 | 70.0000– 700.0000 | 0.565 |

| Procyanidin B1 | C30H26O12 | 8.5 | 577.1323– 577.1381 | 70.0000– 700.0000 | 1.915 |

| Trans Caffeic Acid | C9H8O4 | 8.9 | 179.0340– 179.0358 | 70.0000– 700.0000 | 0.368 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Omachi, D.O.; Shahnaz, T.; Gines, B.; Dawkins, N.; Onuh, J.O. Phytochemical Profiles, In Vitro Antioxidants and Antihypertensive Properties of Wild Blueberries (Vaccinium angustifolium). Foods 2025, 14, 4281. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244281

Omachi DO, Shahnaz T, Gines B, Dawkins N, Onuh JO. Phytochemical Profiles, In Vitro Antioxidants and Antihypertensive Properties of Wild Blueberries (Vaccinium angustifolium). Foods. 2025; 14(24):4281. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244281

Chicago/Turabian StyleOmachi, Deborah O., Thaniyath Shahnaz, Brandon Gines, Norma Dawkins, and John O. Onuh. 2025. "Phytochemical Profiles, In Vitro Antioxidants and Antihypertensive Properties of Wild Blueberries (Vaccinium angustifolium)" Foods 14, no. 24: 4281. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244281

APA StyleOmachi, D. O., Shahnaz, T., Gines, B., Dawkins, N., & Onuh, J. O. (2025). Phytochemical Profiles, In Vitro Antioxidants and Antihypertensive Properties of Wild Blueberries (Vaccinium angustifolium). Foods, 14(24), 4281. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244281