Improving Freeze–Thaw Stability of High-Moisture Extruded Plant-Based Meat: A Synergistic Strategy Combining Glucose Oxidase, Phytase and Tamarind Gum

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Plant-Based Meat with Different Additives

2.3. Freeze–Thaw Treatment

2.4. Carbonyl Content Analysis

2.5. Free and Total Sulfhydral Group Analysis

2.6. Surface Hydrophobicity Analysis

2.7. Tertiary Structure Analysis

2.8. Secondary Structure Analysis

2.9. Low-Field Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (LF-NMR) Analysis

2.10. Water-Holding Capacity (WHC) Analysis

2.11. Texture Profile Analysis (TPA)

2.12. Colorimetric Analysis

2.13. Molecular Dynamics Simulation

2.14. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Analysis of Carbonyl Content

3.2. Analysis of Free Sulfhydral Groups and Total Sulfhydral Groups

3.3. Surface Hydrophobicity Results

3.4. Analysis of Tertiary Structure

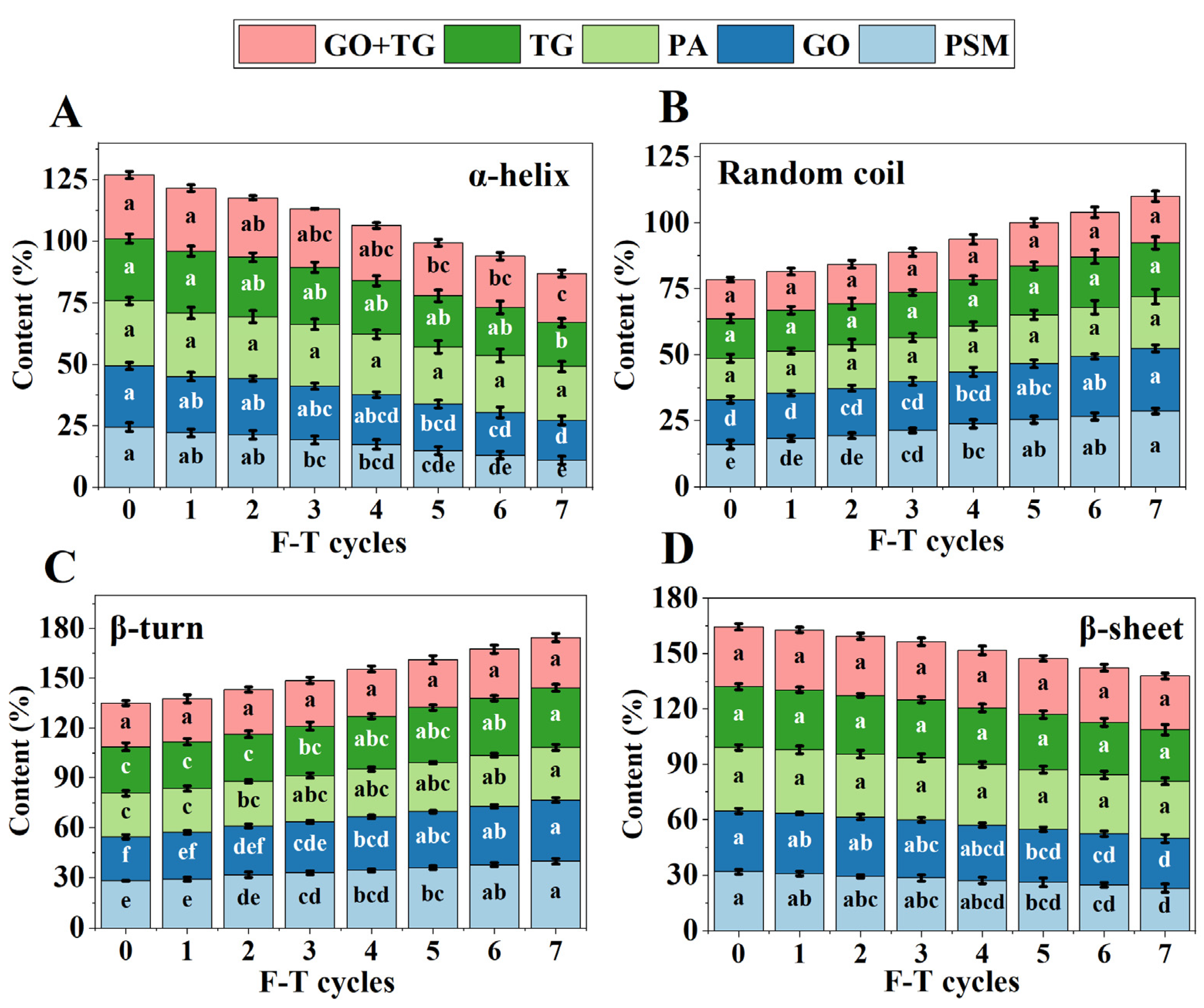

3.5. Secondary Structure Analysis Results

3.6. Low-Field Nuclear Magnetic Analysis

3.7. Water-Holding Capacity

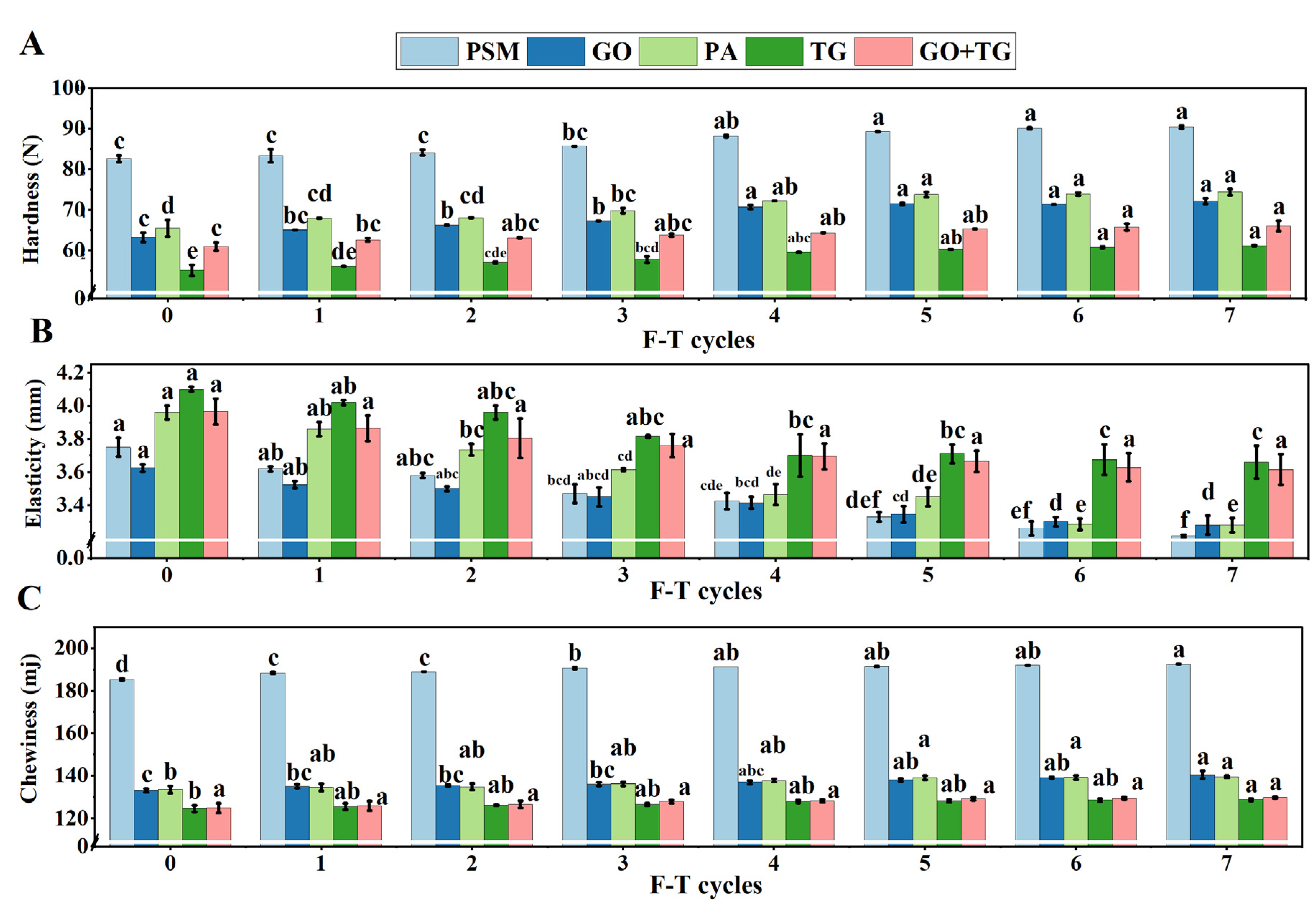

3.8. Texture Characteristic Analysis

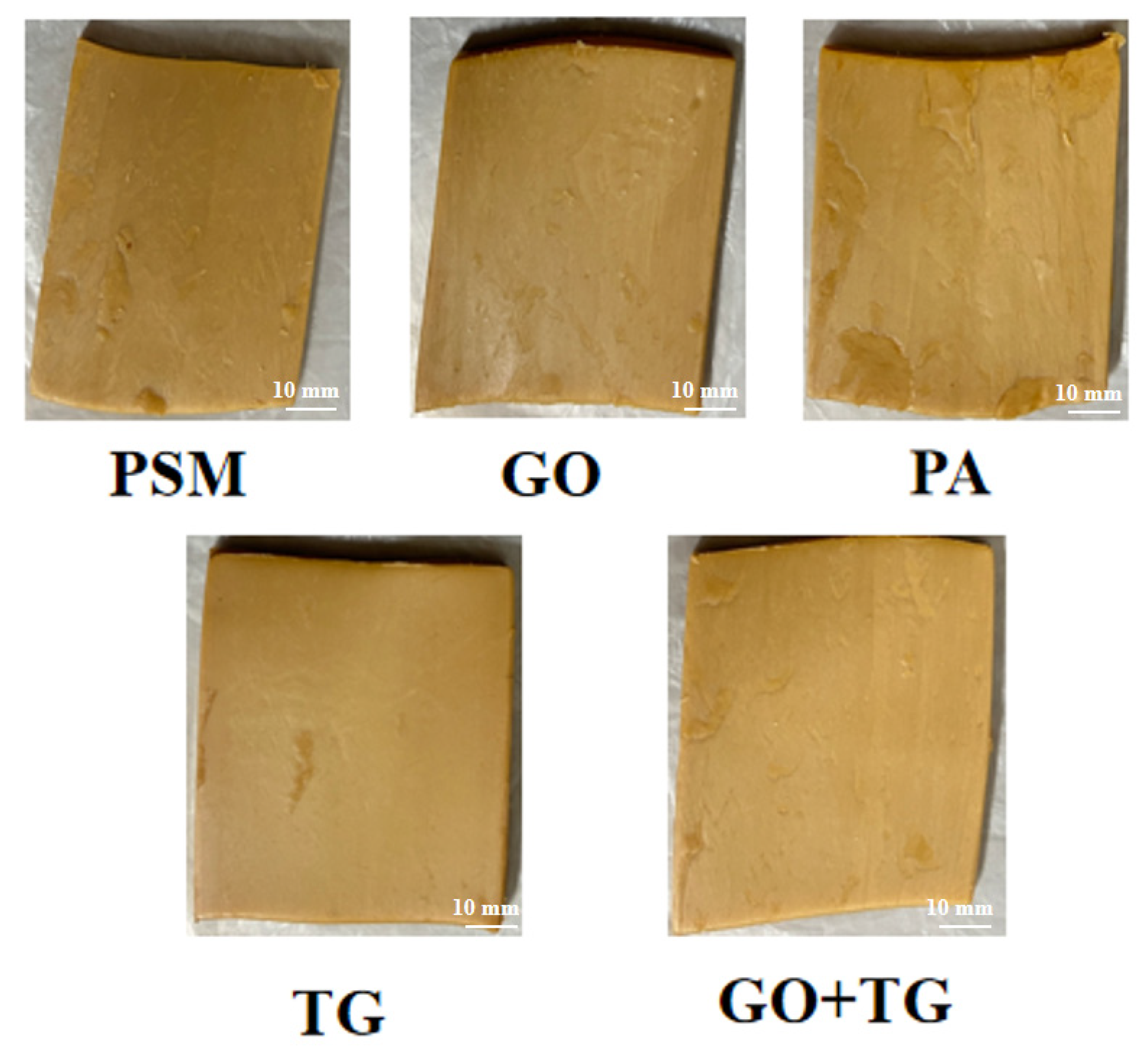

3.9. Color Parameters

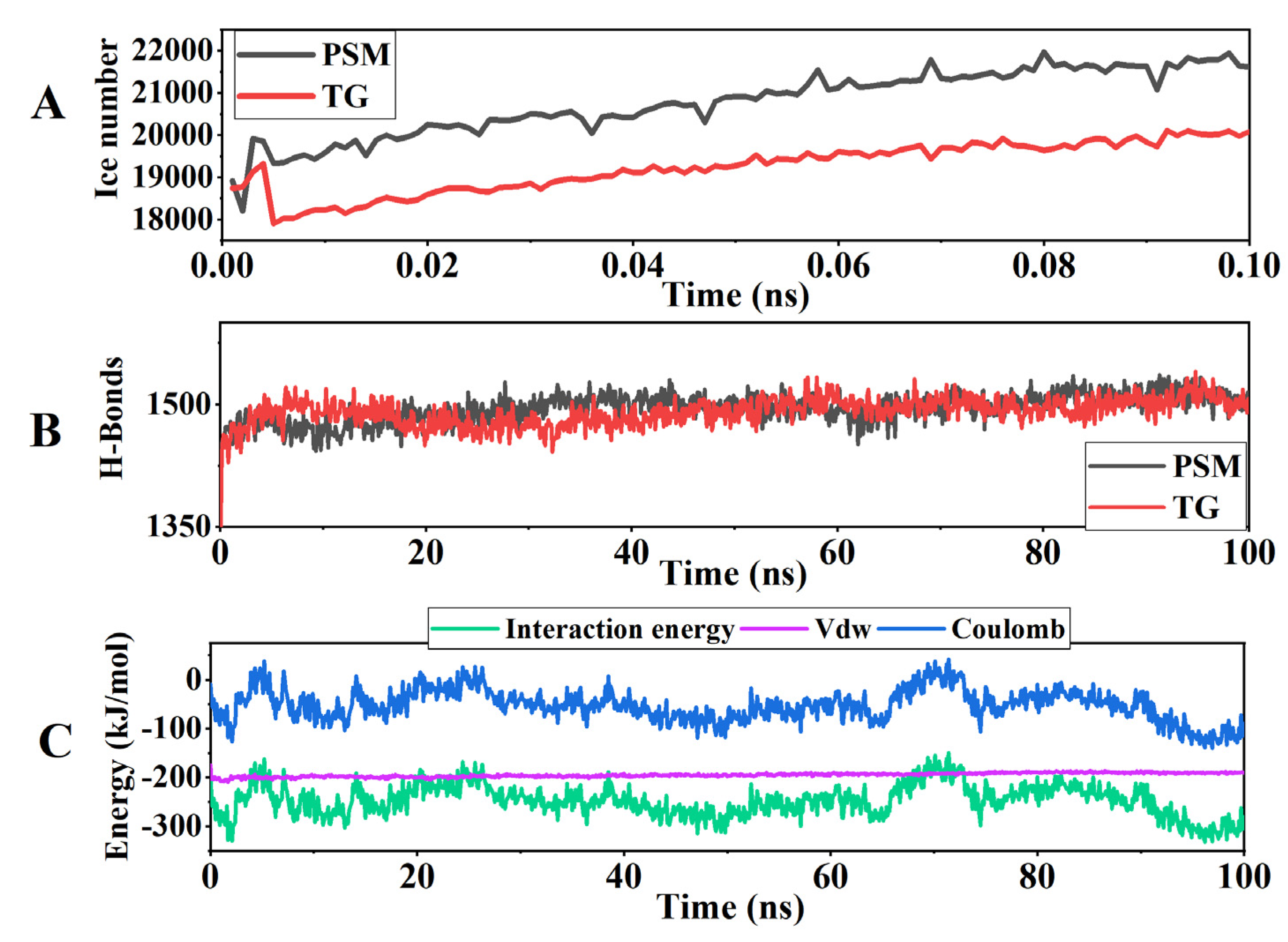

3.10. Molecular Dynamics Simulation Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ran, X.; Yang, H. Promoted strain-hardening and crystallinity of a soy protein-konjac glucomannan complex gel by konjac glucomannan. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 133, 107959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Hu, X.; Xiang, X.; McClements, J.M. Modification of textural attributes of potato protein gels using salts, polysaccharides, and transglutaminase: Development of plant-based foods. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 144, 108909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Hag, L.v.; Haritos, V.; Dhital, S. Rheological and textural properties of heat-induced gels from pulse protein isolates: Lentil, mungbean and yellow pea. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 143, 108904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Fan, L.; Yan, X.; Li, J. Whey protein isolate-tamarind seed gum complexes stabilized dysphagia friendly high internal phase emulsions: The effects of pH conditions and mass ratios. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 159, 110609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-F.; Zhao, X.-H. Structure and property changes of whey protein isolate in response to the chemical modification mediated by horseradish peroxidase, glucose oxidase and D-glucose. Food Chem. 2022, 373, 131328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silventoinen, P.; Kortekangas, A.; Nordlund, E.; Sozer, N. Impact of Phytase Treatment and Calcium Addition on Gelation of a Protein-Enriched Rapeseed Fraction. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2022, 15, 1422–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Kaplan, D.L.; Wang, Q. Protein-amylose/amylopectin molecular interactions during high-moisture extruded texturization toward plant-based meat substitutes applications. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 127, 107559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeno, H.; Hashimoto, R.; Lu, Y.; Hsieh, W.-C. Structural and Mechanical Properties of Konjac Glucomannan Gels and Influence of Freezing-Thawing Treatments on Them. Polymers 2022, 14, 3703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Shi, Y.; Yang, X.; Guo, Q. Flammulina velutipes polysaccharide improves the water-holding capacity in the dorsal muscle of freeze-thawed cultured large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea). Food Chem. 2023, 403, 134401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzova, V.A.; Eronina, T.B.; Mikhaylova, V.V.; Roman, S.G.; Chernikov, A.M.; Chebotareva, N.A. Effect of Chemical Chaperones on the Stability of Proteins during Heat- or Freeze-Thaw Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Han, R.; Yuan, M.; Xi, Q.; Du, Q.; Li, P.; Yang, Y.; Applegate, B.; Wang, J. Ultrasound combined with slightly acidic electrolyzed water thawing of mutton: Effects on physicochemical properties, oxidation and structure of myofibrillar protein. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2023, 93, 106309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Li, S.; Yang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Xia, J.; Zhu, Y.; Li, C. Effect of multiple freeze-thaw cycles on water migration, protein conformation and quality attributes of beef Longissimus dorsi muscle by real-time low field nuclear magnetic resonance and Raman spectroscopy. Food Res. Int. 2023, 166, 112644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, Q.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; He, N.; Wang, Q. High-moisture extrusion process of transglutaminase-modified peanut protein: Effect of transglutaminase on the mechanics of the process forming a fibrous structure. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 112, 106346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, S.; Zhang, K.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Li, M.; Kong, B.; Zhang, C. Role of ultrasonic freezing-treated pork dumpling filling during frozen storage: Insights from protein oxidation, aggregation, and functional properties. Int. J. Refrig. 2024, 165, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katekhong, W.; Phuangjit, U. Modification of Mung Bean Protein Isolate Structure and Functionality by Freeze-Thaw Process. Food Biophys. 2025, 20, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Yang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, X. Effect and mechanism of freezing on the quality and structure of soymilk gel induced by different salt ions. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 5284–5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Cheng, H.; Niu, L.; Xiao, J. Improvement in Freeze-Thaw Stability of Rice Starch by Soybean Protein Hydrolysates-Xanthan Gum Blends and its Mechanism. Starch-Starke 2022, 74, 2100193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Yu, M.; Tan, H.; Zeng, Z.; Xi, Y.; Li, H.; Guo, Z.; Li, J. Mechanistic insights into the effects of controlled enzymatic hydrolysis on the binding behaviors between soy protein isolate and off-flavor compounds. Food Chem. 2025, 467, 142271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Guo, R.; Zhan, T.; Kou, Y.; Ma, X.; Song, H.; Zhou, W.; Song, L.; Zhang, H.; Xie, F.; et al. Retarding ice recrystallization by tamarind seed polysaccharide: Investigation in ice cream mixes and insights from molecular dynamics simulation. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 149, 109579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wang, J.; Hu, H.; Yang, C. Effect of oxidative modification by reactive oxygen species (ROS) on the aggregation of whey protein concentrate (WPC). Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 123, 107189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Dong, Q.; Kong, Y.; Kong, Y.; Yu, Z.; Li, B.; Yan, H.; Chen, X.; Shen, Y. The effect of B-type procyanidin on free radical and metal ion induced β-lactoglobulin glyco-oxidation via mass spectrometry and interaction analysis. Food Res. Int. 2023, 168, 112744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, J.A.; Zámocká, M.; Majtán, J.; Bauerová-Hlinková, V. Glucose Oxidase, an Enzyme “Ferrari”: Its Structure, Function, Production and Properties in the Light of Various Industrial and Biotechnological Applications. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhavya, B.; Sarojini, B.K.; Kodoth, A.K.; Dayananda, B.S.; Venkatesha, R. Fabrication and characterization of tamarind seed gum based novel hydrogel for the targeted delivery of omeprazole magnesium. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 258, 128758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bai, G.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Jin, G.; Teng, W.; Geng, F.; Cao, J. Myofibrillar protein denaturation/oxidation in freezing-thawing impair the heat-induced gelation: Mechanisms and control technologies. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 138, 655–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, N.; Hu, Y.; Li, Y.; Ren, Y.; Kong, B.; Xia, X. Changes in the thermal stability and structure of myofibrillar protein from quick-frozen pork patties with different fat addition under freeze-thaw cycles. Meat Sci. 2021, 175, 108420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, X.; Yang, F.; Wu, J.; Huang, D.; Huang, J.; Wang, S. Effects and mechanism of antifreeze peptides from silver carp scales on the freeze-thaw stability of frozen surimi. Food Chem. 2022, 396, 133717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Du, Z.; Liu, C.; Yu, D.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, J.; Xia, W.; Xu, Y. Uncovering quality changes of surimi-sol based products subjected to freeze-thaw process: The potential role of oxidative modification on salt-dissolved myofibrillar protein aggregation and gelling properties. Food Chem. 2024, 451, 139456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Puolanne, E.; Ertbjerg, P. Mimicking myofibrillar protein denaturation in frozen-thawed meat: Effect of pH at high ionic strength. Food Chem. 2021, 338, 128017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorhirankul, N.; Janssen, A.E.M.; Boom, R.M.B.; Keppler, J.K. Evaluating and Validating the Fluorescent Probe Methodology for Measuring the Effective Hydrophobicity of Protein, Protein Hydrolyzate, and Amino Acid. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 27429–27439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Li, J.; Su, Y.; Gu, L.; Chang, C.; Yang, Y. Sugar alcohols as cryoprotectants of egg yolk: Inhibiting crystals and interactions. J. Food Eng. 2023, 342, 111360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmohammadi, K.; Abedi, E. Enzymatic modifications of gluten protein: Oxidative enzymes. Food Chem. 2021, 356, 129679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suping, J.; Sun, R.; Wang, W.; Xia, Q. Preparation, characterization, and evaluation of tamarind seed polysaccharide-carboxymethylcellulose buccal films loaded with soybean peptides-chitosan nanoparticles. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 141, 108684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Ouyang, Z.; Tao, T.; Zhang, T.; Yan, W.; Li, Y.; Li, B.; Zhu, X. Cyclodextrin induces synergistic cryoprotection with carrageenan oligosaccharide against myofibrillar protein denaturation during fluctuated frozen storage. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 307, 141830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Zhao, Y.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Sui, X. The effect of Hofmeister series anions on the critical overlap concentration of soybean isolate protein. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 149, 109577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.; Guo, J.; Liu, W.; Wu, H.; Zhou, Z. Interrelationship among protein structure, protein oxidation, lipid oxidation and quality of grass carp surimi during multiple freeze-thaw cycles with different pork backfat contents. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, Y.; Guo, R.; Li, X.; Sun, X.; Song, H.; Song, L.; Guo, Y.; Song, Z.; Yuan, C.; Wu, Y. Synthesis, physicochemical and emulsifying properties of OSA-modified tamarind seed polysaccharides with different degrees of substitution. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Zheng, J.; Ke, Z.; Dong, J. Macromolecular crowding effect on the R-galactosidase cascade reaction under multivalency and chain overlapping conditions of glycopolymers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 313, 144343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yang, R.; Feng, X.; Fan, X.; Liu, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhou, G.; Zhu, B.; Ullah, N.; Chen, L. Effects of low-frequency and high-intensity ultrasonic treatment combined with curdlan gels on the thermal gelling properties and structural properties of soy protein isolate. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 127, 107506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Yang, C.; Bruce, H.L.; Roy, B.C.; Li, X.; Zhang, C. Effects of alternating electric field assisted freezing-thawing-aging sequence on Longissimus dorsi muscle microstructure and protein characteristics. Food Chem. 2023, 409, 135266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canal-Martín, A.; Pérez-Fernández, R. Biomimetic selenocystine based dynamic combinatorial chemistry for thiol-disulfide exchange. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juanjuan, D.; Cao, J.; Zhou, C.; Pan, D.; Geng, F.; Wang, Y. Insight into the mechanism of myosin-fibrin gelation induced by non-disulfide covalent cross-linking. Food Res. Int. 2022, 156, 111168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Cheng, S.; Wang, S.; Yi, K.; Sun, S.; Lin, J.; Tan, M.; Li, D. Effect of pre-frying on distribution of protons and physicochemical qualities of mackerel. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 4838–4846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, W.; Yin, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Fang, W.; Liu, Y.; Wakisaka, M.; Zhu, J. Optimizing plant-based meat alternatives: Effects of soy protein incorporation methods and freeze-thaw processing on microstructure and quality. Food Chem. 2025, 493, 145894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengzhu, W.; Fan, L.; Yan, X.; Li, J. Stability and lipid oxidation of oil-in-water emulsion stabilized by Maillard conjugates of soybean phosphatidylethanolamine with different polysaccharides. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 156, 110343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, H.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; Lu, M.; Chen, B.; Ai, C.; Teng, H. Effect of x-carrageenan on saltiness perception and texture characteristic related to salt release in low-salt surimi. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 126852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Q.; Liu, J.; Wang, G.; Zhang, A.; Wang, X.; Zhao, X. Effect of freeze-thaw treatment on the structure and texture of soy protein-dextran conjugate gels crosslinked by transglutaminase. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 153, 112443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qinlin, H.; Qiu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liu, L.; Han, T.; Song, Y.; Zhu, X. Impact of freeze-thaw cycles on the structural and quality characteristics of soy protein gels with different 11S/7S protein ratios. Food Chem. 2025, 475, 143329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhiyong, N.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhou, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhao, G.; Chen, J.; Qiao, D.; Xie, F. Partially removing galactose unit on tamarind gum improves the gel-related features of tamarind gum/xanthan gels by strengthening their synergistic assembly. Food Hydrocoll. 2026, 170, 111728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xiao, T.; Ren, J.; Song, T.; Hu, L.; Liu, Y.; Ramaswamy, H.S.; Yu, Y. The influence of pressure-shift freezing based on the supercooling and pressure parameters on the freshwater surimi gel characteristics. Food Res. Int. 2024, 196, 115014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, L.; Chen, L.; Liu, S.; Cui, Q.; Qin, W. Effects of Sequential Enzymolysis and Glycosylation on the Structural Properties and Antioxidant Activity of Soybean Protein Isolate. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Yang, Y.; Bian, X.; Li, X.; Wang, B.; Wang, D.; Su, D.; Liu, L.; Yu, D.; Guo, X.; et al. Physicochemical, Rheological, Structural, Antioxidant, and Antimicrobial Properties of Polysaccharides Extracted from Tamarind Seeds. J. Food Qual. 2022, 2022, 788248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Sun, X.; Kou, Y.; Song, H.; Li, X.; Song, L.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, H.; Li, D.; Liu, Y.; et al. Hydrophobic aggregation via partial Gal removal affects solution characteristics and fine structure of tamarind kernel polysaccharides. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 144, 108726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuyang, R.; Yang, W.; Zhang, H.; Yu, Y.; Hu, X.; Fan, H.; Liu, L.; Lv, M.; Sun, Y.; Shi, Y.; et al. Physicochemical properties and structure of rice dough and protein based on TGase combined with sodium metabisulfite modification. Food Chem. 2025, 468, 142443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Teng, W.; Dong, L.; Cai, Y.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Y. Exploration on antifreeze potential of thawed drip enzymatic hydrolysates on myofibrillar proteins in pork patties during freeze-thaw cycles. Food Chem. 2025, 467, 142248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Geng, J.; Li, P.; Zhao, Y.; Han, J.; Yang, H.; Cao, S. Effect of blanching times and drying temperatures on the color, moisture migrations, microstructures, phytochemicals, and flavors of chili pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Food Chem. 2025, 486, 144690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Z.; Li, K.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, G.; Wu, K.; Hou, X.; Qiao, D.; Jiang, F.; Zhang, B.; Xie, F. Assembly behavior and nano-scale microstructure of tamarind gum/ xanthan synergistic interaction gels. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 157, 110392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, M.S.I.; Nisa, M.S.F.; Akter, R.; Hasan, M.A.; Hasan, M.M.; Uddin, K.B.; Khan, M.; Kamal, M. Active and intelligent packaging technology for Hilsa (Tenualosa ilisha). Appl. Food Res. 2024, 4, 100644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawooth, M.; Qureshi, D.; Prasad, M.P.J.G.; Mohanty, B.; Alam, M.A.; Anis, A.; Sarkar, P.; Pal, K. Synthesis and characterization of novel tamarind gum and rice bran oil-based emulgels for the ocular delivery of antibiotics. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 1608–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Wang, W.; Huang, Y.; Xia, Q. Tamarind seed polysaccharide-guar gum buccal films loaded with resveratrol-bovine serum albumin nanoparticles: Preparation, characterization, and mucoadhesiveness assessment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 262, 130078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | F-T Cycles | LF-NMR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bound Water/T21 | Non-Flowing Water/T22 | Free Water/T23 | Relative Area Response/P21 (%) | Relative Area Response/P22 (%) | Relative Area Response/P23 (%) | ||

| PSM | 1 | 199.72 ± 1.99 a | 201.49 ± 1.67 a | 1.03 ± 0.15 b | 1035.32 ± 1.41 a | 2762.07 ± 47.02 c | 4.73 ± 0.73 c |

| 3 | 181.51 ± 1.7 b | 191.52 ± 1.16 b | 1.51 ± 0.13 a | 874.82 ± 3.53 b | 3725.8 ± 0.83 a | 224.98 ± 0.47 b | |

| 5 | 166.01 ± 2.36 c | 173.29 ± 1.59 c | 0.87 ± 0.07 b | 799.38 ± 1.65 c | 2995.35 ± 1.57 b | 225.87 ± 0.74 ab | |

| 7 | 115.74 ± 0.75 d | 126.6 ± 1.82 d | 0.09 ± 0 c | 496.06 ± 1.48 d | 2636.72 ± 5.01 d | 227.02 ± 0.01 a | |

| PA | 0 | 199.72 ± 1.99 a | 201.49 ± 1.67 a | 1.03 ± 0.15 b | 1035.32 ± 1.41 a | 2762.07 ± 47.02 c | 4.73 ± 0.73 c |

| 1 | 130.26 ± 0.08 b | 140.76 ± 0.64 b | 3.47 ± 0.29 a | 881.96 ± 0.49 b | 3820.83 ± 14.87 a | 2.64 ± 0.04 d | |

| 3 | 113.12 ± 0.04 c | 120.27 ± 0.11 c | 1.3 ± 0.01 b | 881.05 ± 0.2 b | 3464.71 ± 2.27 b | 199.84 ± 0.74 b | |

| 5 | 110.25 ± 1.54 c | 118.99 ± 0.92 c | 1.29 ± 0.01 b | 880.31 ± 0.42 b | 3464.5 ± 4.49 b | 200.82 ± 0.71 ab | |

| 7 | 110.28 ± 0.05 c | 119.33 ± 0.02 c | 1.05 ± 0.06 b | 880.19 ± 0.04 b | 3416.89 ± 0.49 b | 201.91 ± 0.99 a | |

| TG | 0 | 199.72 ± 1.99 a | 201.49 ± 1.67 a | 1.03 ± 0.15 cd | 1035.32 ± 1.41 a | 2762.07 ± 47.02 d | 4.73 ± 0.73 d |

| 1 | 102.33 ± 1.43 b | 109.81 ± 0.71 b | 2.34 ± 0.01 a | 901.78 ± 0.8 c | 4031.98 ± 0.94 a | 1.14 ± 0.03 e | |

| 3 | 89.26 ± 0.07 c | 90.19 ± 0.04 c | 1.24 ± 0.04 b | 892.71 ± 0.71 d | 3620.29 ± 1.48 b | 123.6 ± 0.06 c | |

| 5 | 88.98 ± 0.05 c | 89.46 ± 0.21 c | 1.2 ± 0.01 bc | 901.71 ± 0.71 c | 3542.73 ± 28.94 c | 125.24 ± 0.04 b | |

| 7 | 87.66 ± 0.49 c | 88.22 ± 0.13 c | 1.02 ± 0.01 d | 905.67 ± 0.49 b | 3509.17 ± 3.19 c | 127.75 ± 0.79 a | |

| GO | 0 | 199.72 ± 1.99 a | 201.49 ± 1.67 a | 1.03 ± 0.15 b | 1035.32 ± 1.41 a | 2762.07 ± 47.02 c | 4.73 ± 0.73 b |

| 1 | 109.81 ± 0.71 b | 127.68 ± 3.76 b | 1.64 ± 0.4 a | 889.27 ± 1.49 b | 3860.18 ± 50.96 a | 2.24 ± 0.11 c | |

| 3 | 91.74 ± 0.81 c | 111.29 ± 1.49 c | 0.87 ± 0.04 b | 886.81 ± 0.71 b | 3380.59 ± 214.14 b | 180.83 ± 0.69 a | |

| 5 | 89.26 ± 1.34 c | 109.63 ± 0.54 c | 0.84 ± 0.04 b | 861.84 ± 3.58 c | 3461.11 ± 8.53 b | 181.83 ± 0.69 a | |

| 7 | 89.35 ± 0.96 c | 109.58 ± 0.52 c | 0.78 ± 0.01 b | 850.31 ± 1.41 d | 3458.24 ± 47.98 b | 182.14 ± 1.17 a | |

| GO + TG | 0 | 199.72 ± 1.99 a | 201.49 ± 1.67 a | 1.03 ± 0.15 b | 1035.32 ± 1.41 a | 2762.07 ± 47.02 c | 4.73 ± 0.73 d |

| 1 | 103.93 ± 0.45 b | 105.31 ± 1.41 b | 1.38 ± 0.04 a | 990.81 ± 0.71 b | 4226.28 ± 14.04 a | 1.28 ± 0.01 e | |

| 3 | 87.26 ± 0.07 c | 79.22 ± 0.13 c | 0.57 ± 0 c | 978.82 ± 0.7 c | 4030.76 ± 2.05 b | 109.86 ± 0.74 a | |

| 5 | 86.3 ± 0.02 c | 79.25 ± 0.06 c | 0.53 ± 0.01 c | 977.61 ± 0.57 c | 4012.91 ± 0.99 b | 102.91 ± 0.99 b | |

| 7 | 86.33 ± 0.19 c | 79.03 ± 0.03 c | 0.51 ± 0.03 c | 976.96 ± 0.07 c | 4006.07 ± 1.21 b | 101.23 ± 0.02 c | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Zeng, X.; Li, J. Improving Freeze–Thaw Stability of High-Moisture Extruded Plant-Based Meat: A Synergistic Strategy Combining Glucose Oxidase, Phytase and Tamarind Gum. Foods 2025, 14, 4270. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244270

Wang X, Zeng X, Li J. Improving Freeze–Thaw Stability of High-Moisture Extruded Plant-Based Meat: A Synergistic Strategy Combining Glucose Oxidase, Phytase and Tamarind Gum. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4270. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244270

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xuzeng, Xiangquan Zeng, and Jian Li. 2025. "Improving Freeze–Thaw Stability of High-Moisture Extruded Plant-Based Meat: A Synergistic Strategy Combining Glucose Oxidase, Phytase and Tamarind Gum" Foods 14, no. 24: 4270. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244270

APA StyleWang, X., Zeng, X., & Li, J. (2025). Improving Freeze–Thaw Stability of High-Moisture Extruded Plant-Based Meat: A Synergistic Strategy Combining Glucose Oxidase, Phytase and Tamarind Gum. Foods, 14(24), 4270. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244270