A Machine Learning Model to Reframe the Concept of Shelf-Life in Bakery Products: PDO Sourdough as a Technological Preservation Model

Abstract

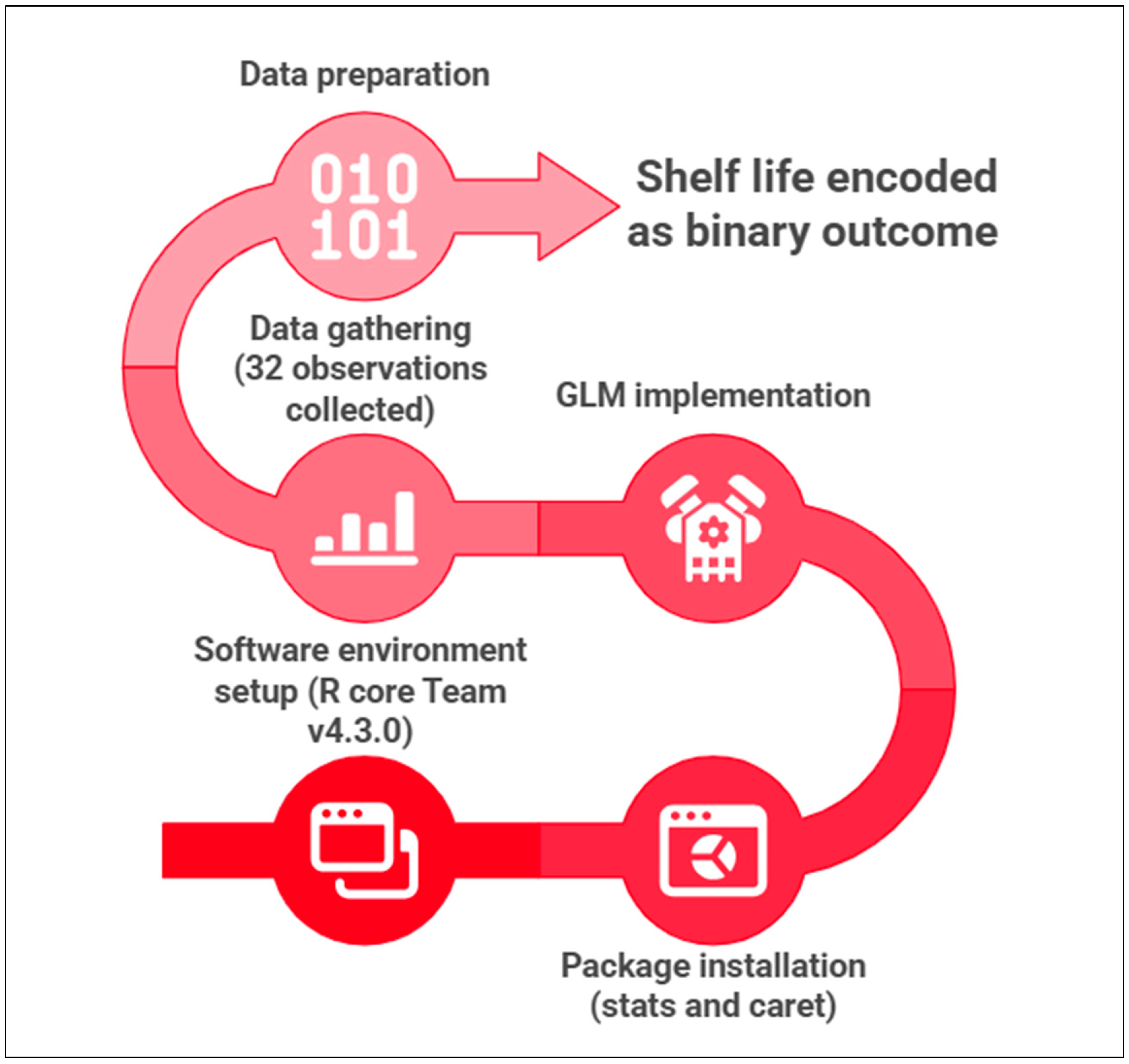

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

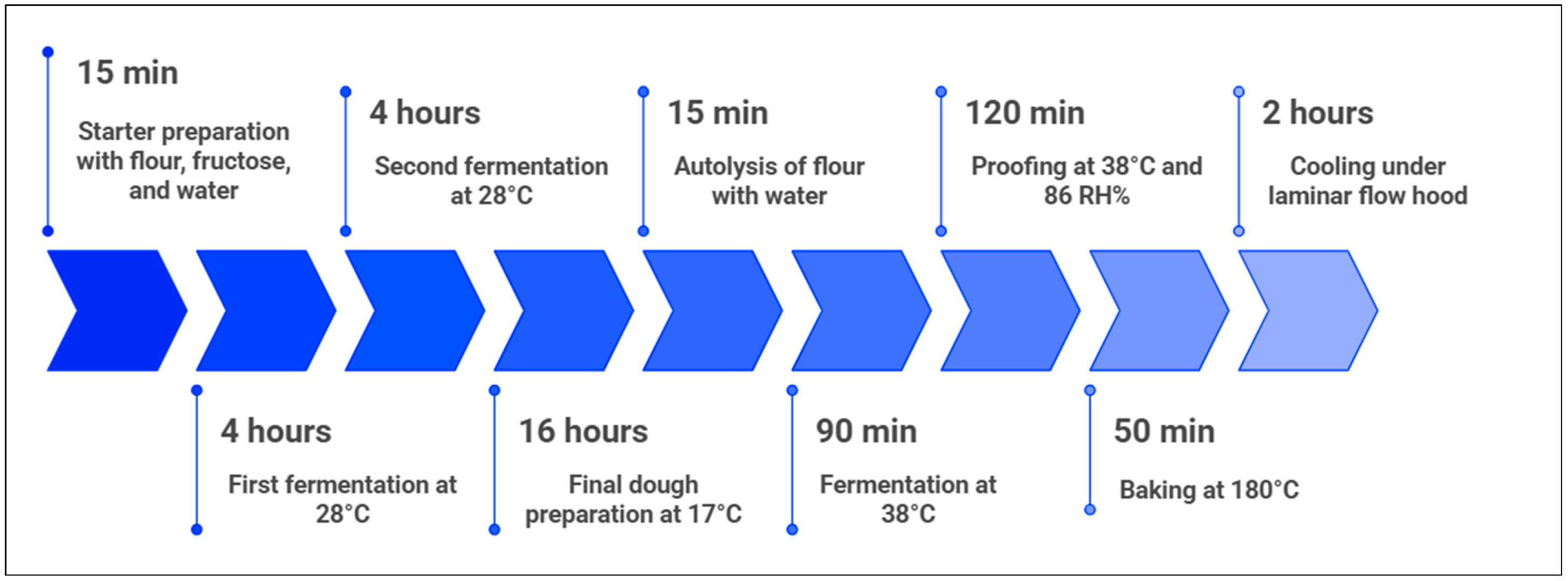

2.2. Breadmaking Process and Sampling Schedule with Analytical Frequency

2.3. Physicochemical Monitoring

2.3.1. pH Physicochemical Determination

2.3.2. Aw Physicochemical Determination

2.3.3. TTA Physicochemical Determination

2.3.4. Fermentative Metabolites Determination

2.3.5. Texture Analysis

2.4. ML Model (GLM Approach)

- β0 is the intercept;

- β1–β4 are the estimated regression coefficients describing the contribution of each variable to the log-odds of shelf-life acceptability.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

- represents the observed value of the dependent variable under the i-th fermentation type, j-th temperature, and k-th atmosphere condition;

- is the overall mean;

- , , and are the main effects of Fermentation, Temperature, and Atmosphere;

- , , and are the two-way interactions among these factors;

- is the random error term, assumed to be normally distributed with zero mean and homogeneous variance ( ).

3. Results and Discussion

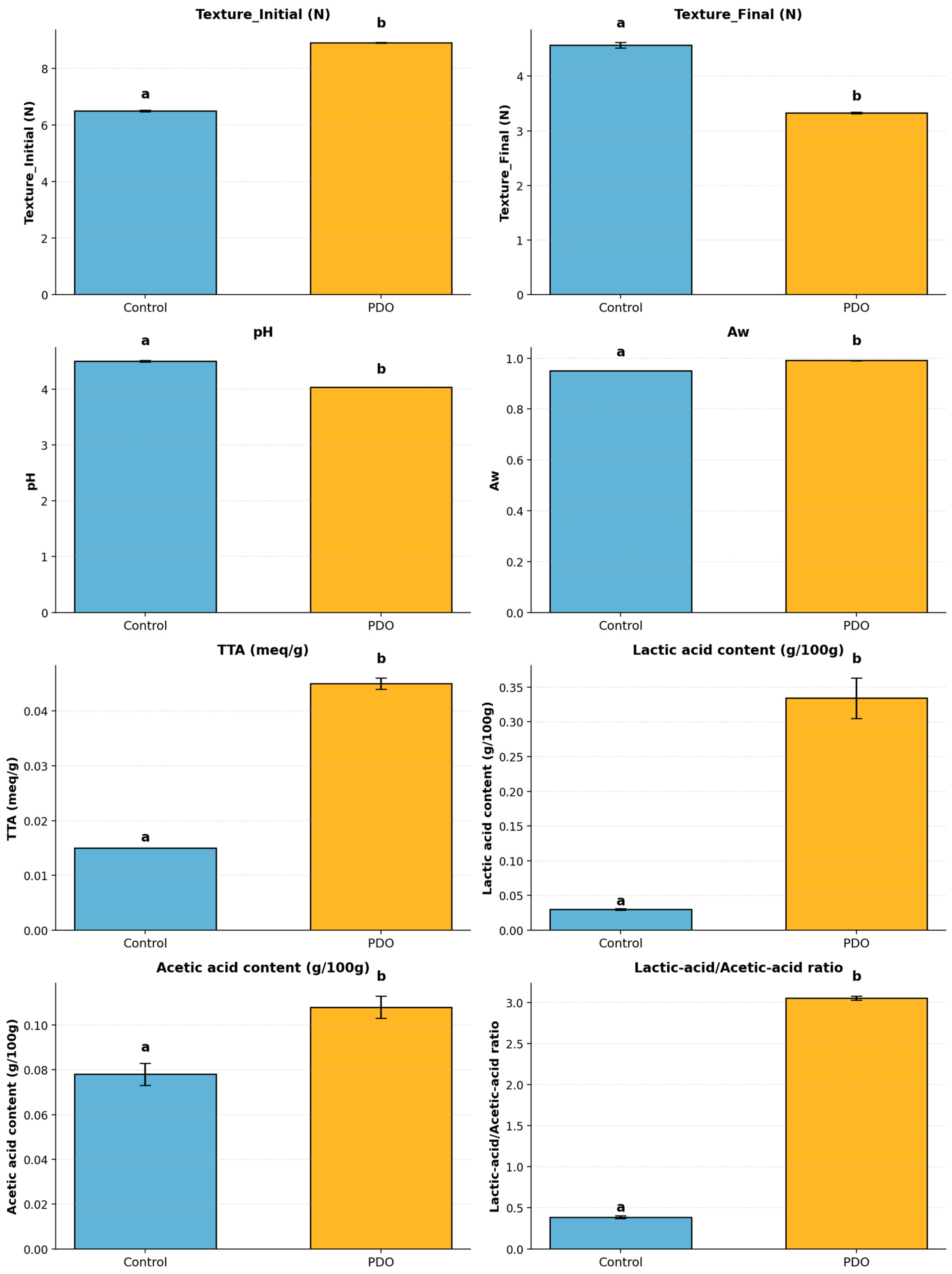

3.1. Redefinition of the Spoilage Trajectory

3.2. Physicochemical Mediation Emerges Before SL Outcome

3.3. Environmental Dominance in ANOVA Supports a Threshold-Mediated Mechanism

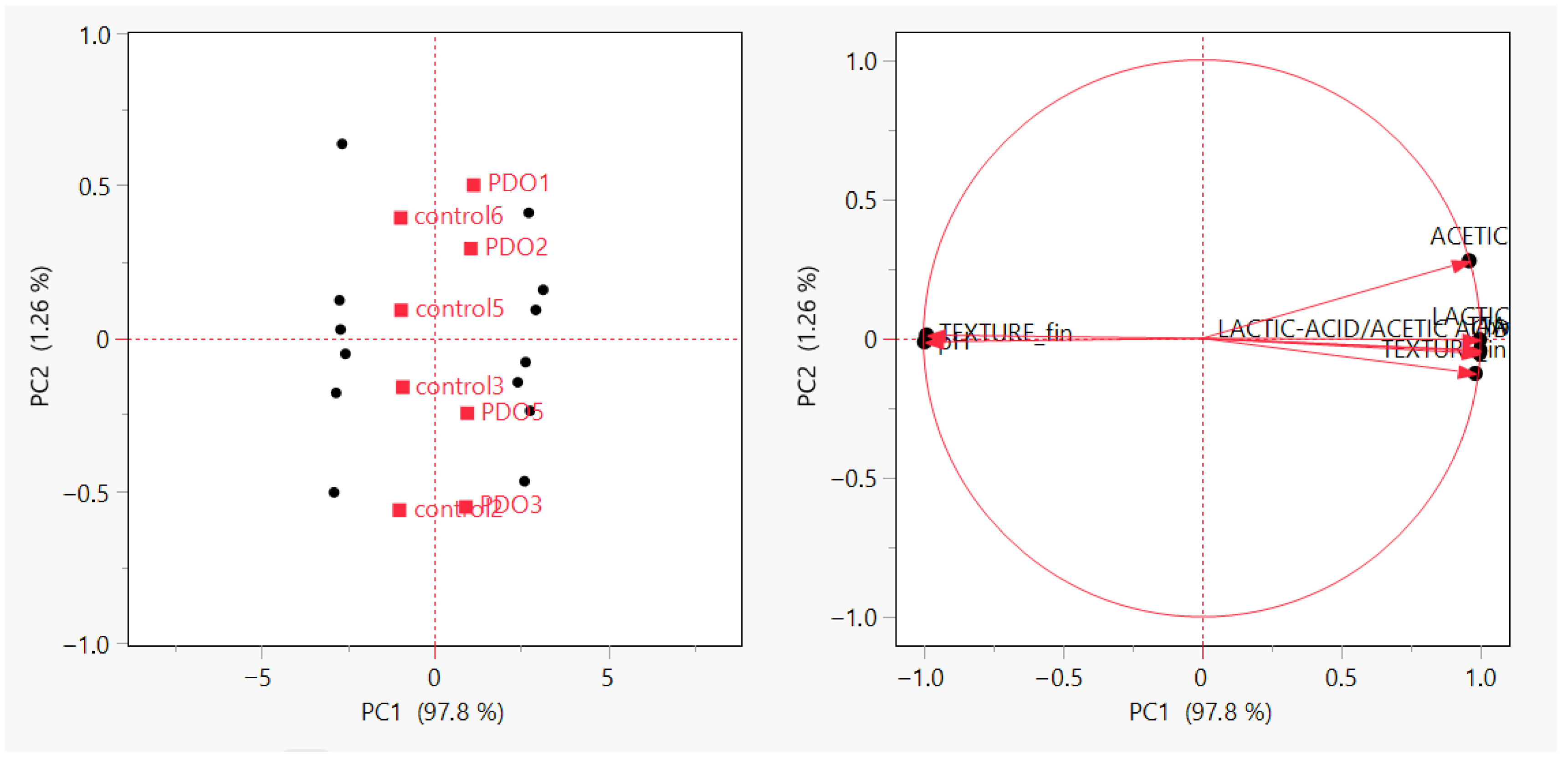

3.4. PCA Reveals Acidification as the Latent Structure Governing SL

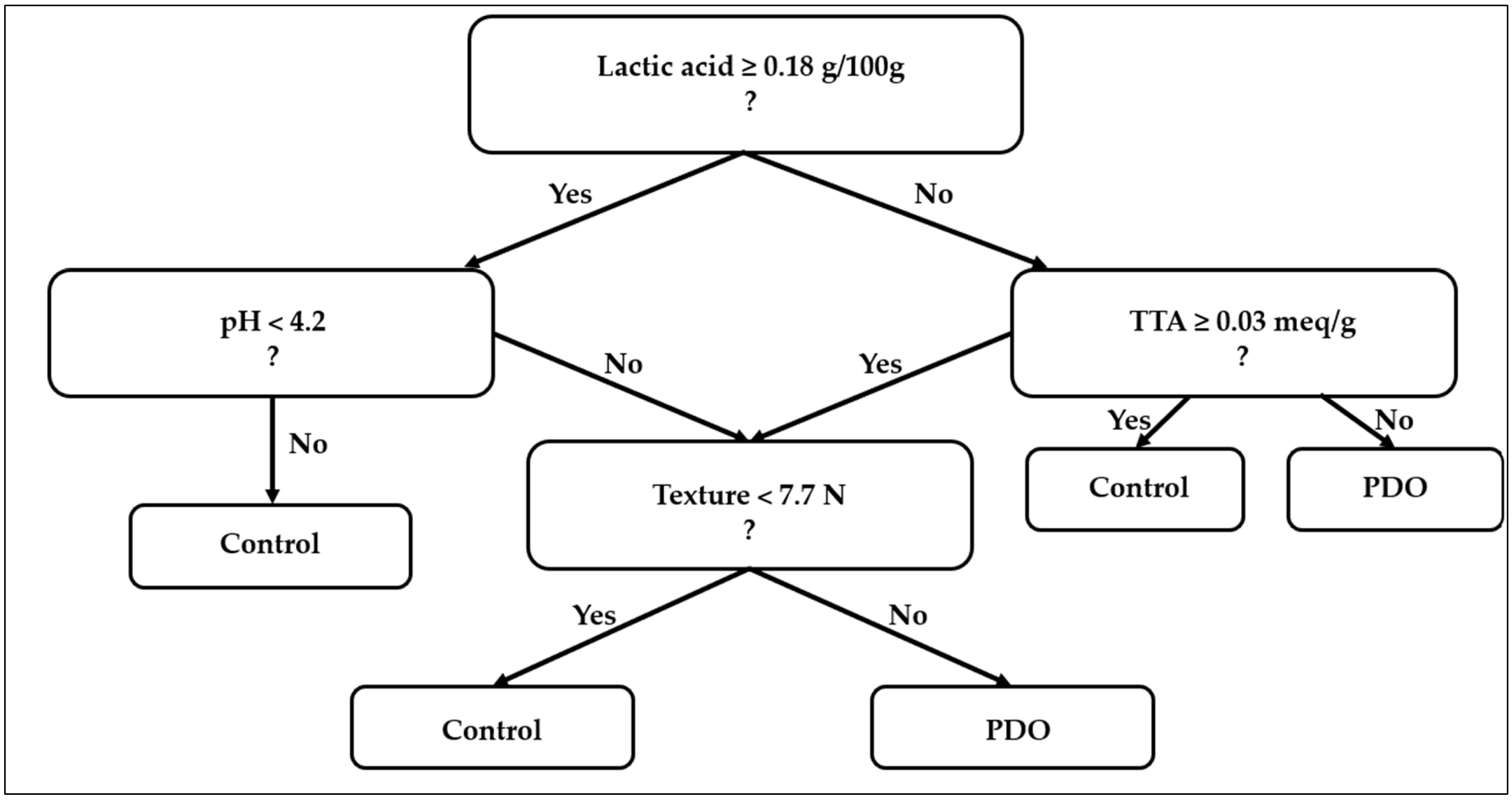

3.5. GLM Modeling Confirms Mediation and Explains Complete Separation

3.6. From Chemical Factors to the Mediation and Activation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PDO | Bread prepared with the Tuscan Bread PDO sourdough |

| Control | Bread prepared with baker’s yeast |

| SL | Shelf-Life |

| MAP | Modified Atmosphere Packaging |

| PET | Polyethylene |

| F | Fermentation |

| T | Temperature (4 °C; 20 °C) |

| A | Atmosphere (AIR; 100% CO2) |

| ML | Machine Learning Model |

| GLM | Generalized Linear Model |

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| TTA | Titratable Acidity |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| RF | Random Forest Model |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine Model |

| QC | Quality Control |

References

- Coda, R.; Cagno, R.D.; Gobbetti, M.; Rizzello, C.G. Sourdough Lactic Acid Bacteria: Exploration of Non-Wheat Cereal-Based Fermentation. Food Microbiol. 2014, 37, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, M.; Minervini, F.; Siragusa, S.; Rizzello, C.G.; Gobbetti, M. Wholemeal Wheat Flours Drive the Microbiome and Functional Features of Wheat Sourdoughs. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 302, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koistinen, V.M.; Mattila, O.; Katina, K.; Poutanen, K.; Aura, A.-M.; Hanhineva, K. Metabolic Profiling of Sourdough Fermented Wheat and Rye Bread. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 5684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S. Handbook of Food Preservation, 3rd ed.; Rahman, M.S., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-0-429-09148-3. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana, F.; Longhi, G.; Alessandri, G.; Lugli, G.A.; Mancabelli, L.; Tarracchini, C.; Viappiani, A.; Anzalone, R.; Ventura, M.; Turroni, F.; et al. Multifactorial Microvariability of the Italian Raw Milk Cheese Microbiota and Implication for Current Regulatory Scheme. mSystems 2023, 8, e01068-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vero, L.; Iosca, G.; Gullo, M.; Pulvirenti, A. Functional and Healthy Features of Conventional and Non-Conventional Sourdoughs. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quattrini, M.; Liang, N.; Fortina, M.G.; Xiang, S.; Curtis, J.M.; Gänzle, M. Exploiting Synergies of Sourdough and Antifungal Organic Acids to Delay Fungal Spoilage of Bread. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 302, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axel, C.; Zannini, E.; Arendt, E.K. Mold Spoilage of Bread and Its Biopreservation: A Review of Current Strategies for Bread Shelf Life Extension. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3528–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, R.S.; Chavan, S.R. Sourdough Technology—A Traditional Way for Wholesome Foods: A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2011, 10, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Lu, W.; Song, Y.; Liu, S.; Fu, Y.V. Using Machine Learning to Identify Environmental Factors That Collectively Determine Microbial Community Structure of Activated Sludge. Environ. Res. 2024, 260, 119635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampieri, G.; Vijayakumar, S.; Yaneske, E.; Angione, C. Machine and Deep Learning Meet Genome-Scale Metabolic Modeling. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2019, 15, e1007084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuperlovic-Culf, M. Machine Learning Methods for Analysis of Metabolic Data and Metabolic Pathway Modeling. Metabolites 2018, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddeo, M.M.; Amorim, L.D. Causal Mediation for Survival Data: A Unifying Approach via GLM. Rev. Colomb. Estad. 2022, 45, 161–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ter Braak, C.J.F.; Peres-Neto, P.; Dray, S. A Critical Issue in Model-Based Inference for Studying Trait-Based Community Assembly and a Solution. PeerJ 2017, 5, e2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albert, J.M.; Nelson, S. Generalized Causal Mediation Analysis. Biometrics 2011, 67, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiura, S.; Abe, H.; Koyama, K.; Koseki, S. Bayesian Generalized Linear Model for Simulating Bacterial Inactivation/Growth Considering Variability and Uncertainty. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 674364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gänzle, M.G.; Zheng, J. Lifestyles of Sourdough Lactobacilli—Do They Matter for Microbial Ecology and Bread Quality? Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 302, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warton, D.I.; Lyons, M.; Stoklosa, J.; Ives, A.R. Three Points to Consider When Choosing a LM or GLM Test for Count Data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 882–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marianelli, A.; Pieracci, Y.; Scappaticci, G.; Macaluso, M.; Guazzotti, M.; Gualco, S.; Zinnai, A. The Role of Flours and Leavening Systems on the Formation of Acrylamide in the Technological Process of Baked Products: Cases Studies of Bread and Biscuits. LWT 2025, 217, 117387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scappaticci, G.; Mercanti, N.; Pieracci, Y.; Ferrari, C.; Mangia, R.; Marianelli, A.; Macaluso, M.; Zinnai, A. Bread Improvement with Nutraceutical Ingredients Obtained from Food By-Products: Effect on Quality and Technological Aspects. Foods 2024, 13, 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Karboune, S. A Review of Bread Qualities and Current Strategies for Bread Bioprotection: Flavor, Sensory, Rheological, and Textural Attributes. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 1937–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagar, N.A.; Pareek, S. Fortification of Multigrain Flour with Onion Skin Powder as a Natural Preservative: Effect on Quality and Shelf Life of the Bread. Food Biosci. 2021, 41, 100992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedemair, V.; Gruber, K.; Knöpfle, N.; Bach, K.E. Technological Changes in Wheat-Based Breads Enriched with Hemp Seed Press Cakes and Hemp Seed Grit. Molecules 2022, 27, 1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, A.; Venturi, F.; Palermo, C.; Taglieri, I.; Angelini, L.G.; Tavarini, S.; Sanmartin, C. Primary and Secondary Shelf-Life of Bread as a Function of Formulation and MAP Conditions: Focus on Physical-Chemical and Sensory Markers. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2024, 41, 101241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaike, H. A New Look at the Statistical Model Identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1974, 19, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M.; Johnson, K. Applied Predictive Modeling; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4614-6848-6. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A Power Primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, A.; Anderson, J.A. On the Existence of Maximum Likelihood Estimates in Logistic Regression Models. Biometrika 1984, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debonne, E.; Vermeulen, A.; Bouboutiefski, N.; Ruyssen, T.; Van Bockstaele, F.; Eeckhout, M.; Devlieghere, F. Modelling and Validation of the Antifungal Activity of DL-3-Phenyllactic Acid and Acetic Acid on Bread Spoilage Moulds. Food Microbiol. 2020, 88, 103407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, M.P.; Russo, P.; Spano, G.; Capozzi, V. From Microbial Ecology to Innovative Applications in Food Quality Improvements: The Case of Sourdough as a Model Matrix. J 2020, 3, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vuyst, L.; Comasio, A.; Kerrebroeck, S.V. Sourdough Production: Fermentation Strategies, Microbial Ecology, and Use of Non-Flour Ingredients. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 2447–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gänzle, M.; Ripari, V. Composition and Function of Sourdough Microbiota: From Ecological Theory to Bread Quality. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 239, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teleky, B.-E.; Martău, A.G.; Ranga, F.; Chețan, F.; Vodnar, D.C. Exploitation of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Baker’s Yeast as Single or Multiple Starter Cultures of Wheat Flour Dough Enriched with Soy Flour. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illueca, F.; Moreno, A.; Calpe, J.; Nazareth, T.D.M.; Dopazo, V.; Meca, G.; Quiles, J.M.; Luz, C. Bread Biopreservation through the Addition of Lactic Acid Bacteria in Sourdough. Foods 2023, 12, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Figueroa, R.H.; Mani-López, E.; Palou, E.; López-Malo, A. Sourdoughs as Natural Enhancers of Bread Quality and Shelf Life: A Review. Fermentation 2023, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calasso, M.; Marzano, M.; Caponio, G.R.; Celano, G.; Fosso, B.; Calabrese, F.M.; De Palma, D.; Vacca, M.; Notario, E.; Pesole, G.; et al. Shelf-Life Extension of Leavened Bakery Products by Using Bio-Protective Cultures and Type-III Sourdough. LWT 2023, 177, 114587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axel, C.; Brosnan, B.; Zannini, E.; Peyer, L.C.; Furey, A.; Coffey, A.; Arendt, E.K. Antifungal Activities of Three Different Lactobacillus Species and Their Production of Antifungal Carboxylic Acids in Wheat Sourdough. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 1701–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peleg, M.; Normand, M.D. Simulating Shelf Life Determination by Two Simultaneous Criteria. Food Res. Int. 2015, 78, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Hsu, J.C.; Bretz, F.; Hayter, A.J.; Han, Y. Shelf-Life and Its Estimation in Drug Stability Studies. J. Appl. Stat. 2014, 41, 1989–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinshov, V.V.; Nekorkin, V.I.; Kurths, J. Stability Threshold Approach for Complex Dynamical Systems. New J. Phys. 2015, 18, 013004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovaleva, A.; Manevitch, L.I. Limiting Phase Trajectories and Emergence of Autoresonance in Nonlinear Oscillators. Phys. Rev. E 2013, 88, 024901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzello, C.G.; Cassone, A.; Coda, R.; Gobbetti, M. Antifungal Activity of Sourdough Fermented Wheat Germ Used as an Ingredient for Bread Making. Food Chem. 2011, 127, 952–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleinikova, Y.; Amangeldi, A.; Zhaksylyk, A.; Saubenova, M.; Sadanov, A. Sourdough Microbiota for Improving Bread Preservation and Safety: Main Directions and New Strategies. Foods 2025, 14, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.I.H.; Sablani, S.S.; Nayak, R.; Gu, Y. Machine Learning-based Modeling in Food Processing Applications: State of the Art. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 1409–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Mittal, K.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, U.; Upadhyay, P. Impact of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in the Food Industry: A Survey. In Advances in Computational Intelligence and Robotics; Khan, M.A., Khan, R., Praveen, P., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 190–215. ISBN 978-1-6684-5141-0. [Google Scholar]

- El-Mesery, H.S.; ElMesiry, A.H.; Husein, M.; Hu, Z.; Salem, A. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Models for Predicting and Evaluating the Influence of Shelf-Life Environments and Packaging Materials on Garlic (Allium sativum L) Physicochemical and Phytochemical Compositions. Food Chem. X 2025, 29, 102731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablegue, A.G.M.-D.; Zhang, M.; Guo, Q.; Rui, L. Monitoring and Shelf Life Extension of Food Products Based on Machine Learning and Deep Learning: Progress and Potential Applications. Food Rev. Int. 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribet, L.; Dessalles, R.; Lesens, C.; Brusselaers, N.; Durand-Dubief, M. Nutritional Benefits of Sourdoughs: A Systematic Review. Adv. Nutr. 2023, 14, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Jia, J.; Liu, G.; Liang, S.; Huang, Y.; Xin, M.; Chang, Z.; Liu, X.; Ma, C.; Song, X.; et al. Polysaccharides Extracted from Old Stalks of Asparagus officinalis L. Improve Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver by Increasing the Gut Butyric Acid Content and Improving Gut Barrier Function. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 6632–6645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Huang, X.; Guo, J.; Hu, Y.; Gafurov, K.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.; Guo, Q. Synergistic Modification of Sunflower Seed Protein by pH-Cycling and Ultrasound to Improve Its Structural and Functional Properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2026, 172, 112017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Storage Phase (Days) | Frequency (Days) | Units Analysed | Quality Status at Sampling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early storage phase (0–16) | Every 4 | Control + PDO | Stable |

| Mid-storage phase (16–30) | Every 6–8 | Control + PDO | Initial Fungal Growth |

| Late storage phase (30–54) | Every 10–12 | PDO + Control ATM | Hardening texture-limited, Fungal Growth |

| Parameter | Control (Mean ± SD) | PDO (Mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Texture_Initial (N) | 6.494 ± 0.030 a | 8.910 ± 0.010 b |

| Texture_Final (N) | 4.568 ± 0.050 a | 3.328 ± 0.015 b |

| pH | 4.503 ± 0.014 a | 4.034 ± 0.001 b |

| Aw | 0.950 ± 0.000 a | 0.991 ± 0.001 b |

| TTA (meq/g) | 0.015 ± 0.000 a | 0.045 ± 0.001 b |

| Lactic acid content (g/100 g) | 0.030 ± 0.001 a | 0.334 ± 0.029 b |

| Acetic acid content (g/100 g) | 0.078 ± 0.005 a | 0.108 ± 0.005 b |

| Lactic acid/Acetic acid ratio | 0.387 ± 0.018 a | 3.056 ± 0.024 b |

| Parameters | F | T | A | F × T | F × A | T × A | F × T × A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Texture_Initial (N) | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns | ns |

| Texture_Final (N) | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns | ns |

| pH | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns | *** |

| Aw | *** | ns | ns | *** | *** | ns | ns |

| TTA (meq/g) | *** | *** | *** | *** | *** | ns | ** |

| Lactic acid content (g/100 g) | *** | ns | ns | *** | *** | ns | *** |

| Acetic acid content (g/100/g) | *** | *** | ns | *** | *** | ns | *** |

| Lactic acid/Acetic acid ratio | *** | *** | ns | *** | *** | ns | *** |

| Parameters | Value (%) | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Accuracy 1 | 89.0 ± 1.5 | Cross-validation result |

| Sensitivity (Recall) 2 | 91.5 ± 2.2 | True positive rate |

| Specificity 3 | 86.5 ± 2.0 | True negative rate |

| Precision 4 | 88.0 ± 1.2 | Positive predictive value |

| F1-Score 5 | 89.7 ± 1.6 | Harmonic mean of precision and recall |

| AUC-ROC 6 | 92.0 ± 1.2 | Area under ROC curve |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marianelli, A.; Offei, C.A.; Macaluso, M.; Mercanti, N.; Casu, B.; Zinnai, A. A Machine Learning Model to Reframe the Concept of Shelf-Life in Bakery Products: PDO Sourdough as a Technological Preservation Model. Foods 2025, 14, 4236. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244236

Marianelli A, Offei CA, Macaluso M, Mercanti N, Casu B, Zinnai A. A Machine Learning Model to Reframe the Concept of Shelf-Life in Bakery Products: PDO Sourdough as a Technological Preservation Model. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4236. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244236

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarianelli, Andrea, Cecilia Akotowaa Offei, Monica Macaluso, Nicola Mercanti, Bruno Casu, and Angela Zinnai. 2025. "A Machine Learning Model to Reframe the Concept of Shelf-Life in Bakery Products: PDO Sourdough as a Technological Preservation Model" Foods 14, no. 24: 4236. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244236

APA StyleMarianelli, A., Offei, C. A., Macaluso, M., Mercanti, N., Casu, B., & Zinnai, A. (2025). A Machine Learning Model to Reframe the Concept of Shelf-Life in Bakery Products: PDO Sourdough as a Technological Preservation Model. Foods, 14(24), 4236. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244236