Efficient Decolorization and Preparation of Sparassis crispa Polysaccharides Using Amino-Modified Silica Gel and Evaluation of Their Biological Activites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials, Reagents and Experimental Animals

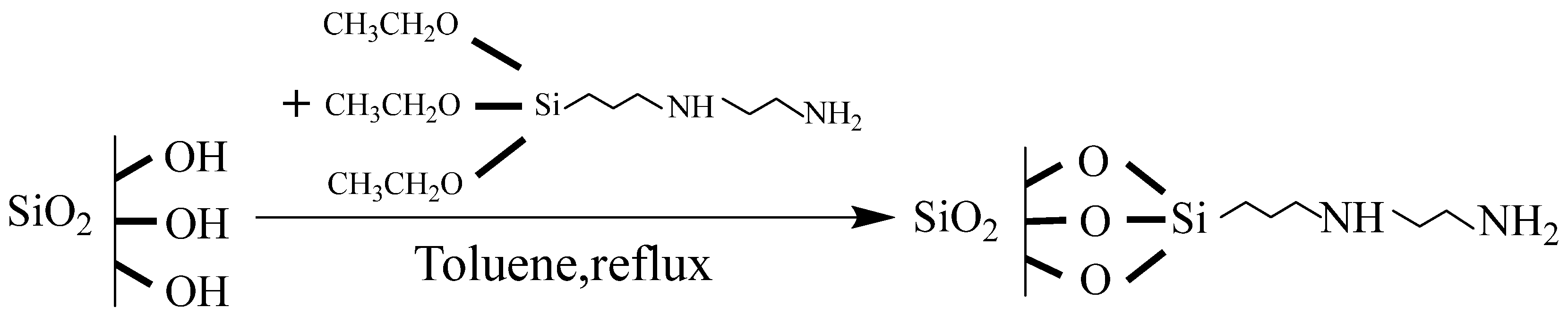

2.2. Preparation of Amino-Modified Silica Gel

2.3. Structural Characterization of Silica Gel

2.3.1. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.3.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.3.3. N2 Adsorption–Desorption Analysis

2.3.4. X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

2.4. Extraction of Crude Polysaccharides from S. crispa

2.5. Adsorption of Pigments from Crude Polysaccharides by Silica Gel

2.6. Reusability and Regeneration of PSA-2

2.6.1. Reusability Test

2.6.2. Regeneration Test

2.7. Preparation of H2O2 Decolorized Polysaccharides

2.8. Bioactivity Evaluation of S. crispa Polysaccharides

2.8.1. In Vitro Antioxidant Activity

- (1)

- DPPH Radical Scavenging

- (2)

- ABTS Radical Scavenging

- (3)

- Hydroxyl Radical Scavenging

2.8.2. Zebrafish Caudal Fin Regeneration

2.9. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Structural Characterization of Silica Gel-Based Decolorizing Adsorbents

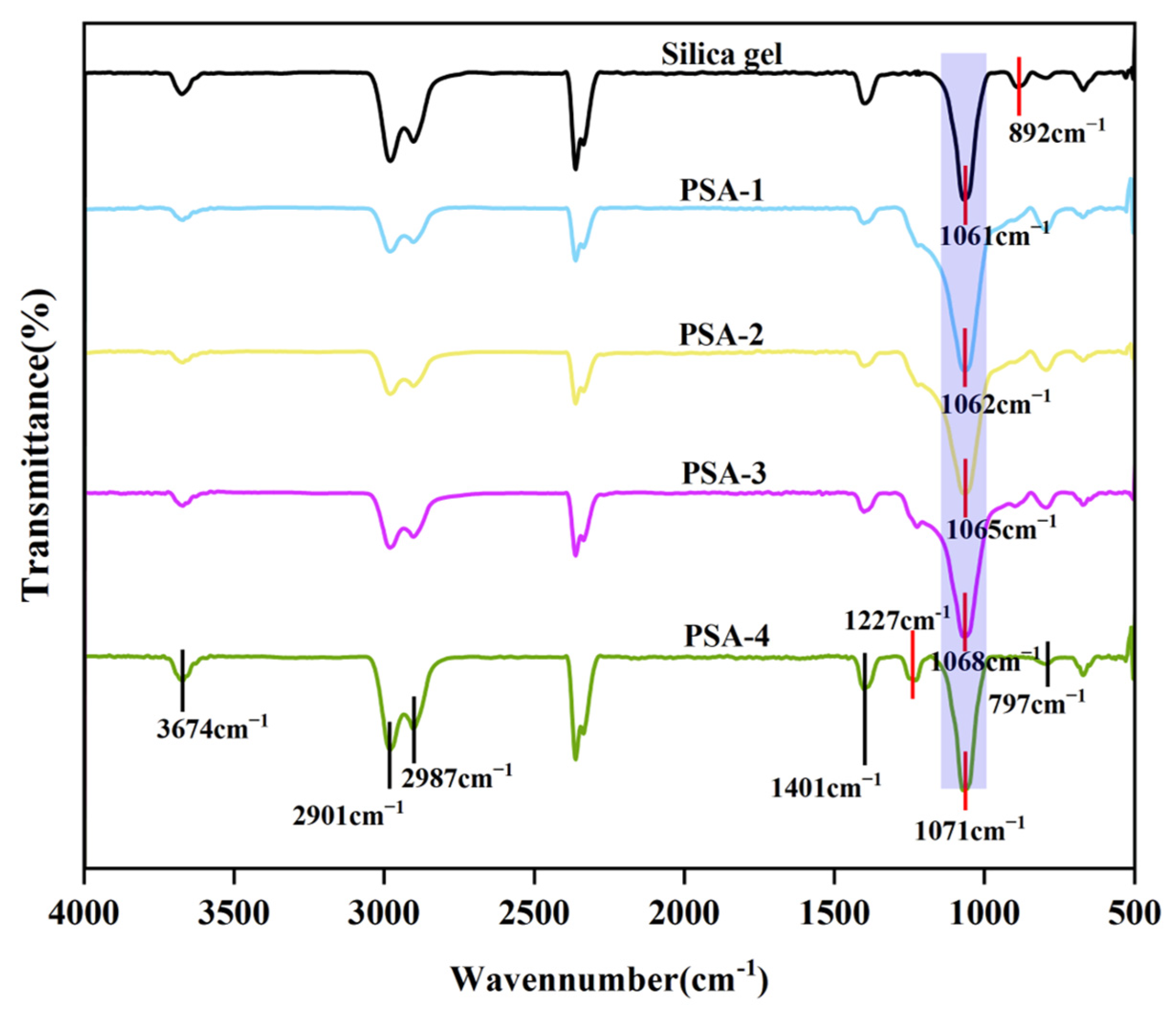

3.1.1. FT-IR Analysis

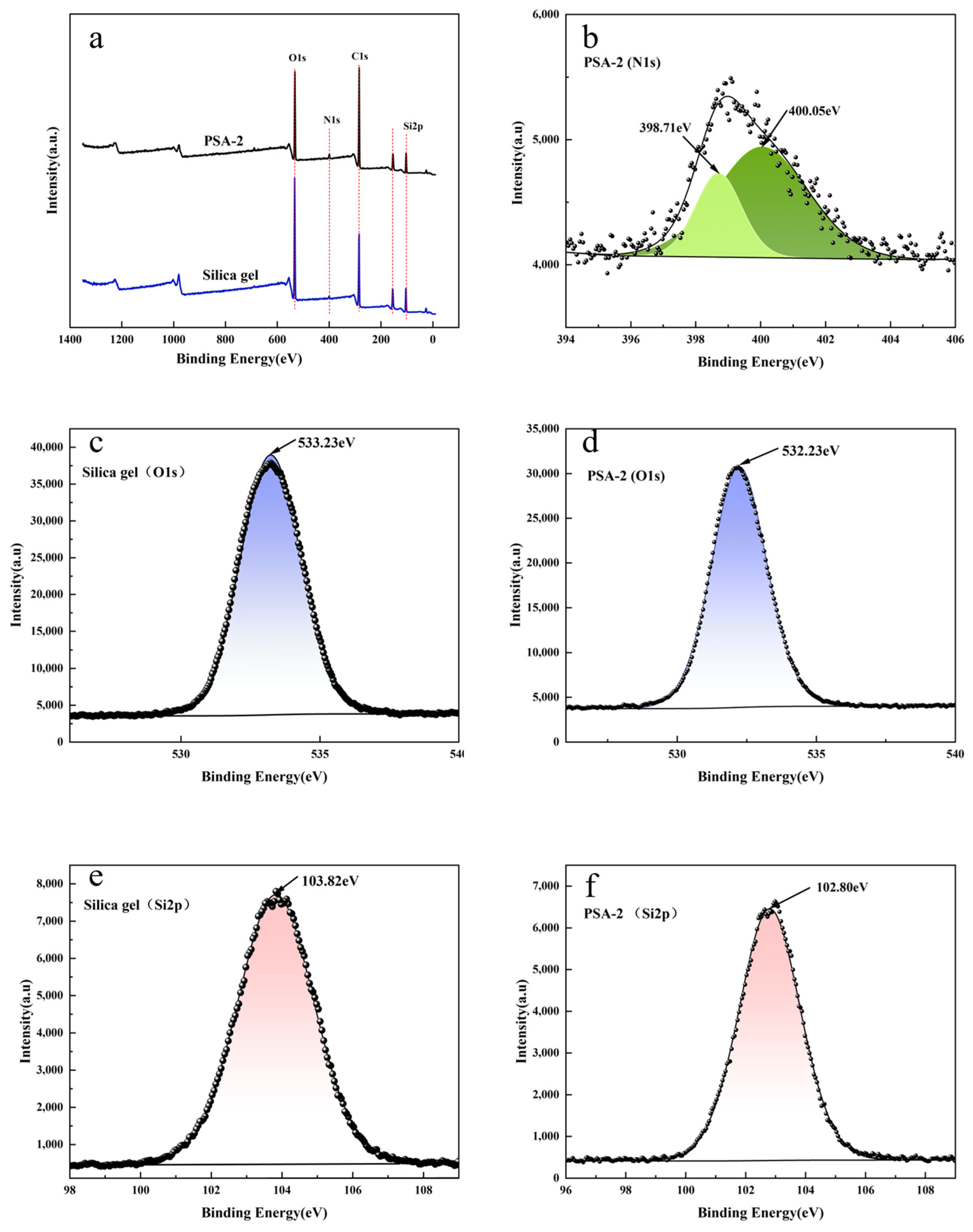

3.1.2. XPS Analysis

3.1.3. SEM Analysis

3.1.4. N2 Adsorption–Desorption Analysis

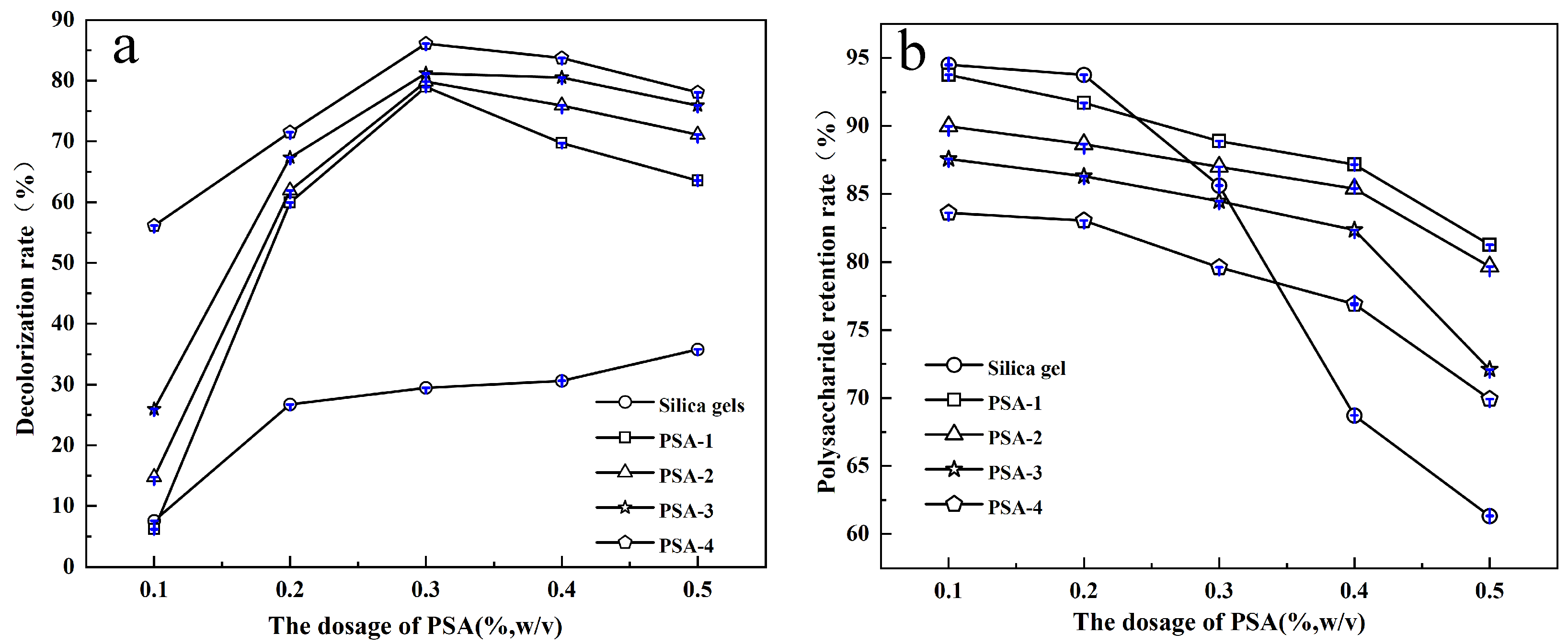

3.2. Decolorization Performance of Adsorbents on S. crispa Polysaccharide Solutions

3.3. Reusability and Regeneration Performance

3.4. Adsorption Mechanism of Modified PSA Toward S. crispa Pigments

3.5. Biological Activities of S. crispa Polysaccharides

3.5.1. Antioxidant Activity of S. crispa Polysaccharides

3.5.2. Regenerative Effects of S. crispa Polysaccharides on Zebrafish Caudal Fin

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PSA | Primary Secondary Amine |

| APS | 3-(2-aminoethylamino)propyltriethoxysilane |

| PCSP | Crude S. crispa polysaccharides |

References

- Liu, M.-Y.; Yun, S.-J.; Cao, J.-L.; Cheng, F.; Chang, M.-C.; Meng, J.-L.; Liu, J.-Y.; Cheng, Y.-F.; Xu, L.-J.; Geng, X.-R.; et al. The fermentation characteristics of Sparassis crispa polysaccharides and their effects on the intestinal microbes in mice. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2021, 8, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Yang, Q.; Chang, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Ren, J. Potential Osteoporosis-Blocker Sparassis Crispa Polysaccharide: Isolation, Purification and Structure Elucidation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 261, 129879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishioka, J.; Hiramoto, K.; Suzuki, K. Mushroom Sparassis crispa (Hanabiratake) Fermented with Lactic Acid Bacteria Significantly Enhances Innate Immunity of Mice. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 43, 629–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacka-Jechalke, N.; Nowak, R.; Lemieszek, M.K.; Rzeski, W.; Gawlik-Dziki, U.; Szpakowska, N.; Kaczyński, Z. Promising Potential of Crude Polysaccharides from Sparassis crispa against Colon Cancer: An In Vitro Study. Nutrients 2021, 13, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Hu, B.; Han, M.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Qian, H. Purification, Structural Characterization and Neuroprotective Effect of a Neutral Polysaccharide from Sparassis crispa. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 201, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Sun, M.; Chen, K.; Wang, L.; Sun, J. Ultrasonic-Assisted Decoloration of Polysaccharides from Seedless Chestnut Rose (Rosa sterilis) Fruit: Insight into the Impact of Different Macroporous Resins on Its Structural Characterization and In Vitro Hypoglycemic Activity. Foods 2024, 13, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Yu, R.; Sun, J.; Duan, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, W.; Li, G. Static Decolorization of Polysaccharides from the Leaves of Rhododendron dauricum: Process Optimization, Characterization and Antioxidant Activities. Process Biochem. 2022, 121, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.; Chen, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Wu, W.; Huang, S.; Li, X.; Luo, H.; Huang, B.; Simal-Gandara, J.; et al. Advances in Research on Dendrobium Officinale Polysaccharide: Extraction Techniques, Structural Features, Biological Functions, Structure-Activity Relationships, Biosynthesis and Resources. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Li, Z.; Gao, R.; Zhao, T.; Luo, D.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Qi, C.; Wang, Y.; Qiao, H.; et al. Structural Characteristics of Rehmannia glutinosa Polysaccharides Treated Using Different Decolorization Processes and Their Antioxidant Effects in Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Foods 2022, 11, 3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; You, L.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Kulikouskaya, V. Influence of UV/H2O2 Treatment on Polysaccharides from Sargassum fusiforme: Physicochemical Properties and RAW 264.7 Cells Responses. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 153, 112246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, L.; Sun, Y.; Liang, J.; Li, M.; Li, X. Decolorization Affects the Structural Characteristics and Antioxidant Activity of Polysaccharides from Thesium chinense Turcz: Comparison of Activated Carbon and Hydrogen Peroxide Decolorization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 155, 1084–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, L.; Ban, M.; Yang, L.; Zeng, Y.; Li, S.; Tang, C.; Zhang, D.; Chen, X. An Effective and Recyclable Decolorization Method for Polysaccharides from: Isaria cicadae Miquel by Magnetic Chitosan Microspheres. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 3147–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Liu, H.; Nie, J.; Tan, J.; Lv, C.; Lu, J. Acidic Polysaccharides of Mountain Cultivated Ginseng: The Potential Source of Anti-Fatigue Nutrients. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 95, 105198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, J.; Ren, X.; Wang, Y. Extraction, Purification and Properties of Water-Soluble Polysaccharides from Mushroom Lepista nuda. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 128, 858–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Liu, T.; Han, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, X.; Ma, X.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, Q. An Efficient Method for Decoloration of Polysaccharides from the Sprouts of Toona sinensis (A. Juss.) Roem by Anion Exchange Macroporous Resins. Food Chem. 2017, 217, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Li, P.; Yang, L.; Wu, L.; He, L.; Gao, F.; Qi, X.; Zhang, Z. Iron/Zinc and Phosphoric Acid Modified Sludge Biochar as an Efficient Adsorbent for Fluoroquinolones Antibiotics Removal. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 196, 110550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhraliieva, A.; Gonçalves, R.A.; Zaitsev, V. Mesoporous Silica with Covalently Immobilized Anthracene as Adsorbent for SPE Recovery of PAHs Pollutants from Highly Lipidic Solutions. Methods Objects Chem. Anal. 2021, 16, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhao, J.; Cui, L.; Wang, X.; Cai, N.; Li, H.; Ren, S.; Li, T.; Shu, L. Synthesis and Structural Characteristics Analysis of Melanin Pigments Induced by Blue Light in Morchella sextelata. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1276457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhong, H.; Zhou, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Han, H.; Qiu, H. Tuning Selectivity via Electronic Interaction: Preparation and Systematic Evaluation of Serial Polar-Embedded Aryl Stationary Phases Bearing Large Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1036, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Gao, L.; Song, L.; Sommerfeld, M.; Hu, Q. An Improved Phenol-Sulfuric Acid Method for the Quantitative Measurement of Total Carbohydrates in Algal Biomass. Algal Res. 2023, 70, 102986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Sun, M.; Geng, N.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Pan, H.; Yang, Q.; Yang, Z.; Lou, Y.; Zhuge, Y. A Novel and Recyclable Silica Gel-Modified Biochar to Remove Cadmium from Wastewater: Model Application and Mechanism Exploration. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 281, 116608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Liu, X.; Gong, X.; Yang, X.; Fang, J.; Liu, J. Mesoporous Core/Shell Structured Silica Gel Composites with Hydrazide-Modified Polyacrylate for High-Efficiency Removal of Formaldehyde with Reduced Carbon Emission Effect. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 370, 133273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, B.; Gonfa, G.; Mekuria Hailegiorgis, S. Preparation of Modified Silica Gel Supported Silver Nanoparticles and Its Evaluation Using Zone of Inhibition for Water Disinfection. Arab. J. Chem. 2024, 17, 106036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Osorio, D.; Nogueira, H.P.; Gonçalves, J.M.; Toma, S.H.; Garcia-Segura, S.; Araki, K. SPION-Decorated Organofunctionalized MCM48 Silica-Based Nanocomposites for Magnetic Solid-Phase Extraction. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Deng, L.; Yuan, P.; Liu, D.; Yuan, W.; Liu, P.; He, H.; Li, Z.; Chen, F. Surface Silylation of Natural Mesoporous/Macroporous Diatomite for Adsorption of Benzene. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2015, 448, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahtabani, A.; La Zara, D.; Anyszka, R.; He, X.; Paajanen, M.; Van Ommen, J.R.; Dierkes, W.; Blume, A. Gas Phase Modification of Silica Nanoparticles in a Fluidized Bed: Tailored Deposition of Aminopropylsiloxane. Langmuir 2021, 37, 4481–4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.M.; Kim, D.M.; Kim, M.H.; Han, J.Y.; Jung, D.K.; Shim, Y.B. A Disposable Amperometric Dual-Sensor for the Detection of Hemoglobin and Glycated Hemoglobin in a Finger Prick Blood Sample. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 91, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radi, S.; Tighadouini, S.; Bacquet, M.; Degoutin, S.; Garcia, Y. New Hybrid Material Based on a Silica-Immobilised Conjugated β-Ketoenol-Bipyridine Receptor and Its Excellent Cu(II) Adsorption Capacity. Anal. Methods 2016, 8, 6923–6931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebretatios, A.G.; Banat, F.; Witoon, T.; Cheng, C.K. Synthesis of Sustainable Rice Husk Ash-Derived Nickel-Decorated MCM-41 and SBA-15 Mesoporous Silica Materials for Hydrogen Storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 51, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Xie, C.; He, G.; Xiao, Y. Fabrication of EDTA Modified Silica Gel toward Highly Efficient Adsorptive Removal of Copper Ions from Methanol. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 370, 133225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, A.; Hauke, F. Post-Graphene 2D Chemistry: The Emerging Field of Molybdenum Disulfide and Black Phosphorus Functionalization. Angew. Chem.—Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 4338–4354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Ren, X.; Li, M.; Sun, J.; Wang, Y.; Yue, T.; Wang, J. A Sustainable and Nondestructive Method to High-Throughput Decolor Lycium barbarum L. Polysaccharides by Graphene-Based Nano-Decoloration. Food Chem. 2021, 338, 127749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofoedu, C.E.; You, L.; Osuji, C.M.; Iwouno, J.O.; Kabuo, N.O.; Ojukwu, M.; Agunwah, I.M.; Chacha, J.S.; Muobike, O.P.; Agunbiade, A.O.; et al. Hydrogen Peroxide Effects on Natural-sourced Polysacchrides: Free Radical Formation/Production, Degradation Process, and Reaction Mechanism—A Critical Synopsis. Foods 2021, 10, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Zhang, J.; Lan, W.; Yu, L.; Bi, Y.; Song, S.; Xiong, B.; Wang, H. Polysaccharide Decolorization: Methods, Principles of Action, Structural and Functional Characterization, and Limitations of Current Research. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 138, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Hu, B.; Liu, C.; Hua, H.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Yao, W.; Qian, H. Comprehensive Analysis of Sparassis crispa Polysaccharide Characteristics during the in Vitro Digestion and Fermentation Model. Food Res. Int. 2022, 154, 111005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji Ganesh, S.; Anees, F.F.; Kaarthikeyan, G.; Martin, T.M.; Kumar, M.S.K.; Sheefaa, M.I. Zebrafish Caudal Fin Model to Investigate the Role of Cissus Quadrangularis, Bioceramics, and Tendon Extracellular Matrix Scaffolds in Bone Regeneration. J. Oral. Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2025, 15, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfefferli, C.; Jaźwińska, A. The Art of Fin Regeneration in Zebrafish. Regeneration 2015, 2, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Shao, J.; Ye, C.; Wang, H.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, Y. Effect of Polysaccharides on Conformational Changes and Functional Properties of Protein-Polyphenol Binary Complexes: A Comparative Study. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 126890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Adsorbents | BET Surface Area (Mean ± SEM, m2/g) | BJH Desorption Cumulative Volume of Pores (Mean ± SEM, cm3/g) | BJH Desorption Average Pore Radius (Mean ± SEM, nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silica gels | 320.57 ± 1.7 (n = 3) | 0.70 ± 0.01 (n = 3) | 7.15 ± 0.02 (n = 3) |

| PSA-1 | 287.90 ± 2.2 (n = 3) | 0.66 ± 0.03 (n = 3) | 7.15 ± 0.04 (n = 3) |

| PSA-2 | 222.13 ± 0.9 (n = 3) | 0.54 ± 0.03 (n = 3) | 5.86 ± 0.02 (n = 3) |

| PSA-3 | 230.71 ± 1.1 (n = 3) | 0.55 ± 0.01 (n = 3) | 6.78 ± 0.03 (n = 3) |

| PSA-4 | 216.30 ± 1.8 (n = 3) | 0.52 ± 0.04 (n = 3) | 6.83 ± 0.03 (n = 3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, J.; Zhang, C.; Peng, C.; Wang, L.; Zheng, S. Efficient Decolorization and Preparation of Sparassis crispa Polysaccharides Using Amino-Modified Silica Gel and Evaluation of Their Biological Activites. Foods 2025, 14, 4214. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244214

Chen J, Zhang C, Peng C, Wang L, Zheng S. Efficient Decolorization and Preparation of Sparassis crispa Polysaccharides Using Amino-Modified Silica Gel and Evaluation of Their Biological Activites. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4214. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244214

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Jiebo, Chunyan Zhang, Cheng Peng, Lu Wang, and Shoujing Zheng. 2025. "Efficient Decolorization and Preparation of Sparassis crispa Polysaccharides Using Amino-Modified Silica Gel and Evaluation of Their Biological Activites" Foods 14, no. 24: 4214. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244214

APA StyleChen, J., Zhang, C., Peng, C., Wang, L., & Zheng, S. (2025). Efficient Decolorization and Preparation of Sparassis crispa Polysaccharides Using Amino-Modified Silica Gel and Evaluation of Their Biological Activites. Foods, 14(24), 4214. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244214