Pretreatment and Thermal Stability of Idesia polycarpa Virgin Oil

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Sample Processing

2.2.1. Drying Methods

2.2.2. Impurity Contents

2.2.3. Filtration Cycles

2.3. Preparation of I. polycarpa Oil

2.4. Determination of Oil Yield and Physicochemical Indices of Oil Samples

2.5. Heating Test

2.6. Determination of the Quality of Heated Fats and Oils

2.7. Statistical Analysis of Data

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effect of Different Pretreatments on the Oil Yield of I. polycarpa Virgin Oil

3.2. Effect of Different Pretreatments on the Quality of Idesia polycarpa Virgin Oil

3.2.1. Effect of Different Drying Methods on the Quality of Idesia polycarpa Virgin Oil

3.2.2. The Effect of Different Impurity Content on the Quality of Idesia polycarpa Virgin Oil

3.2.3. The Effect of Different Filtering Times on the Quality of Idesia polycarpa Virgin Oil

3.3. Changes in the Physicochemical Indices of IPVO, IPRO, SO and RO During the Heating Process

3.3.1. Acid Value

3.3.2. Peroxide Value

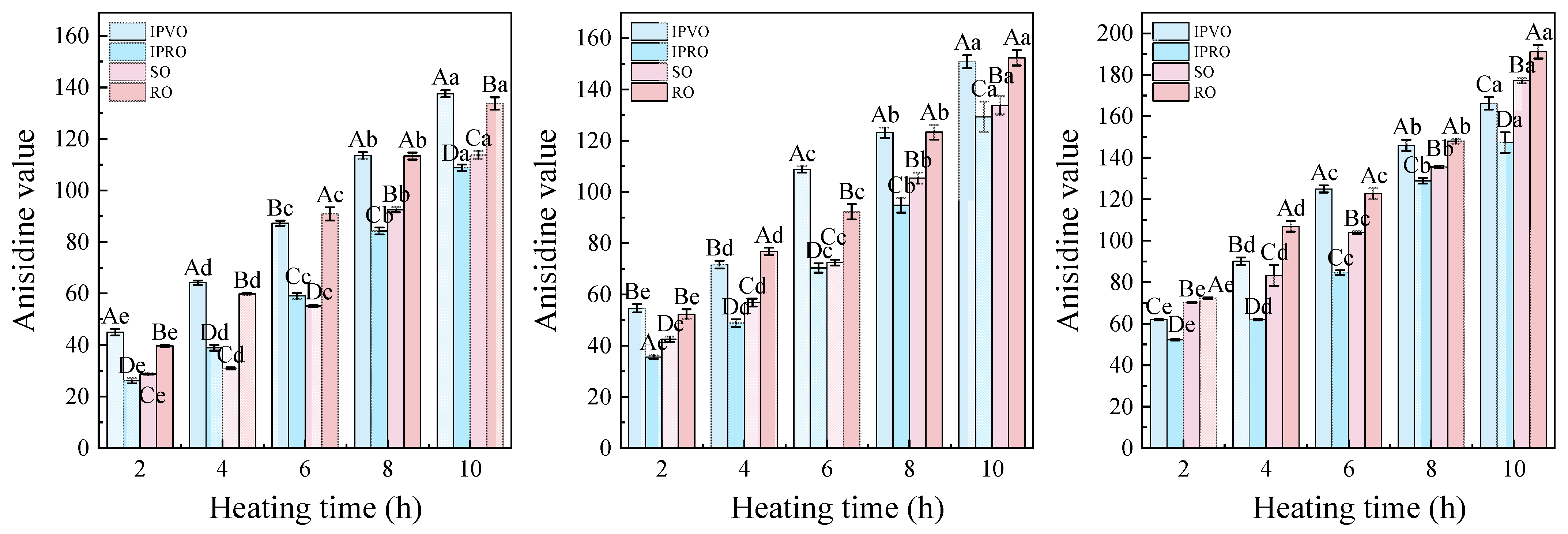

3.3.3. Anisidine Value

3.3.4. Total Oxidation Value

3.3.5. Conjugated Dienes and Conjugated Trienes

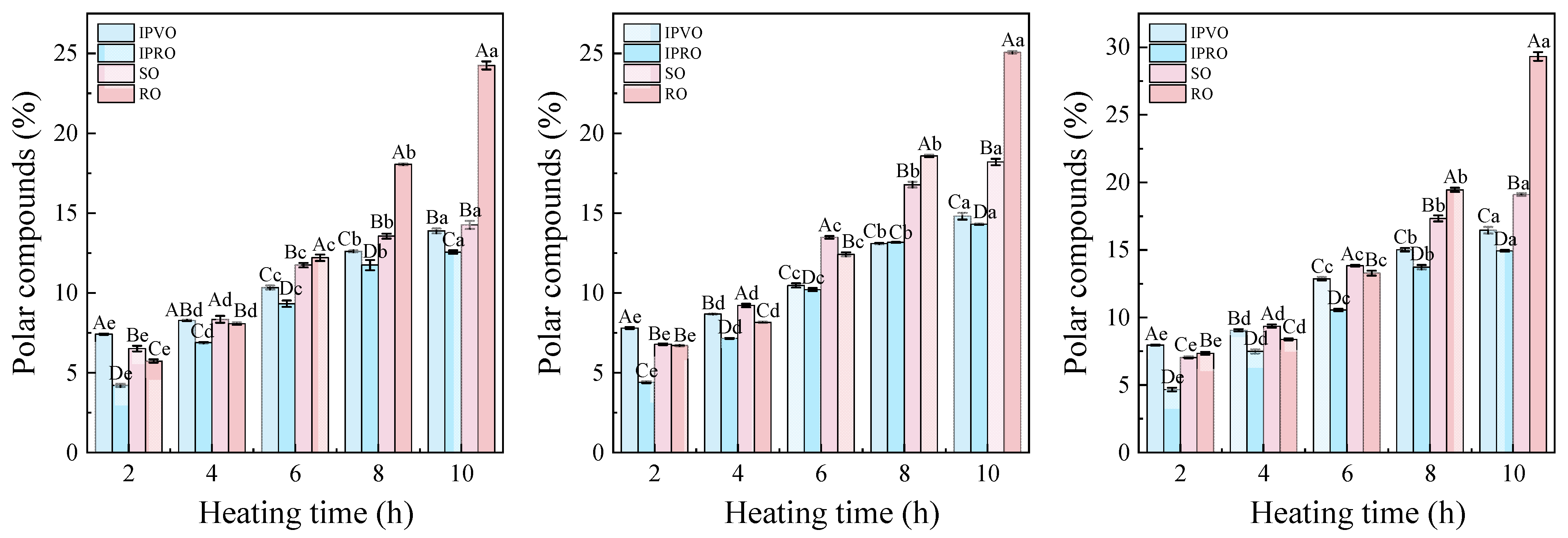

3.3.6. Polar Compounds

3.3.7. Fatty Acid Composition and Trans Fatty Acid Composition

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, Y.; Peng, T.; Huang, L.; Zhang, S.Y.; He, Y.Y.; Tang, L. The evaluation of lipids raw material resources with the fatty acid profile and morphological characteristics of Idesia polycarpa Maxim. var. vestita Diels fruit in harvesting. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 129, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Dong, J.Z.; Gao, Z.C.; Fan, B.L.; Chen, Y.B.; Luo, K.; Zheng, X.J. Subchronic Toxicity Evaluation of Idesia polycarpa Fruit Oil by 90-Day Oral Exposure in Wistar Rats. J. Med. Food 2024, 27, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.L.; Zhao, C.W.; Karrar, E.; Du, M.J.; Jin, Q.Z.; Wang, X.G. Analysis of Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Idesia polycarpa Pulp Oil from Five Regions in China. Foods 2023, 12, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.Y.; Xiang, X.W.; Wang, Z.R.; Yang, Q.Q.; Guo, Z.H.; Huang, P.M.; Mao, J.M.; An, X.F.; Kan, J.Q. Evaluation of cultivars diversity and lipid composition properties of Idesia polycarpa var. vestita Diels. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 3841–3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Sun, Y.R.; He, L.B.; Huang, L.; Li, T.T.; Wang, T.Y.; Tang, L. Amelioration by Idesia polycarpa Maxim. var. vestita Diels. of Oleic Acid-Induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver in HepG2 Cells through Antioxidant and Modulation of Lipid Metabolism. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 1208726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Lee, H.H.; Lee, J.K.; Ye, S.K.; Kim, S.H.; Sung, S.H. Anti-adipogenic activity of compounds isolated from Idesia polycarpa on 3T3-L1 cells. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 3170–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, H.R.; Ge, Y.H.; Liu, W.X.; Yang, J.X.; Zhong, Z.X.; Wang, J.H. Effects of Different Drying Methods on Volatile Flavor Compounds in Idesia polycarpa Maxim Fruit and Oil. Molecules 2025, 30, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, D.; Zhou, X.; Shi, Q.L.; Pan, J.B.; Zhan, H.S.; Ge, F.H. High-pressure supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of Idesia polycarpa oil: Evaluation the influence of process parameters on the extraction yield and oil quality. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 188, 115586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.N.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Y.B.; Huang, X.F.; Yang, W.Q.; Li, S.; Li, S.Y.; Luo, K.; Xin, X.L. A systematic study on composition and antioxidant of 15 varieties of wild Idesia polycarp fruits in China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1292746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.Q.; Huang, R.S.; Wang, L.S.; Ge, Y.H.; Fang, H.G.; Chen, G.J. Comparative study on the effects of different drying technologies on the structural characteristics and biological activities of polysaccharides from Idesia polycarpa maxim cake meal. Food Chem. X 2025, 26, 102348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.S.; Jia, H.J.; Li, X.D.; Liu, Y.L.; Wei, A.C.; Zhu, W.X. Effect of drying methods on the quality of tiger nuts (Cyperus esculents L.) and its oil. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 167, 113827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.S.; Liu, Y.L.; Che, L.M. Effects of different drying methods on the extraction rate and qualities of oils from demucilaged flaxseed. Dry. Technol. 2018, 36, 1642–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.K.; Han, J.J.; Zhao, Z.K.; Tian, J.H.; Fu, X.Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wei, C.Q.; Liu, W.Y. Roasting treatments affect oil extraction rate, fatty acids, oxidative stability, antioxidant activity, and flavor of walnut oil. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1077081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, M.; Golmakani, M.T.; Abbasi, A.; Nader, M. Effects of sesame dehulling on physicochemical and sensorial properties of its oil. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 6596–6603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breschi, C.; Ferraro, G.; Guerrini, L.; Fratini, E.; Calamai, L.; Parenti, A.; Lunetti, L.; Zanoni, B. Composition and Physical Stability of the Colloidal Dispersion in Veiled Virgin Olive Oil. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2023, 125, 2200151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Sánchez, J.; Cerretani, L.; Bendini, A.; Segura-Carretero, A.; Fernández-Gutiérrez, A. Filtration process of extra virgin olive oil: Effect on minor components, oxidative stability and sensorial and physicochemical characteristics. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 21, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortini, M.; Migliorini, M.; Cherubini, C.; Cecchi, L.; Guerrini, L.; Masella, P.; Parenti, A. Shelf life and quality of olive oil filtered without vertical centrifugation. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2016, 118, 1213–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, P.L.; Juncos, N.S.; Grosso, N.R.; Olmedo, R.H. Use of Humulus lupulus and Origanum vulgare as Protection Agents Against Oxidative Deterioration in “Deep-Fried Process”: Frying Model Assay with Sunflower Oil and High-Oleic Peanuts. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2024, 17, 1970–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, F.; Semeniuc, C.A.; Dan, M.; Dippong, T. Impact of different processing methods and thermal behaviour on quality characteristics of soybean and sesame oils. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2024, 149, 1403–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, P.L.; Juncos, N.S.; Grosso, N.R.; Olmedo, R.H. Determination in the efficiency of the use of essential oils of oregano and hop as antioxidants in deep frying processes. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2024, 126, 2300145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarenga, B.R.; Xavier, F.A.N.; Soares, F.L.F.; Carneiro, R.L. Thermal Stability Assessment of Vegetable Oils by Raman Spectroscopy and Chemometrics. Food Anal. Methods 2018, 11, 1969–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.J.; Li, C.F.; Wang, S.S.; Mei, X.F.; Zhang, H.X.; Kan, J.Q. Characterization of physicochemical properties and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides from shoot residues of bamboo (Chimonobambusa quadrangularis): Effect of drying procedures. Food Chem. 2019, 292, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.Y.; Yin, C.J.; Liu, W.K.; Wu, M.J.; Su, L.J.; Chen, P.C. The Drying Method Affects the Physicochemical Properties, Antioxidant Activity, and Volatile Flavor of Sargassum fusiforme. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2024, 2024, 4717136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M. Study on Extraction and Refining Process Optimization and Anti-Oxidation of Idesia polycarpa Oil. Master’s thesis, Guizhou University, Guiyang, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.; Wu, W.G.; Wu, S.H.; Wu, J.L.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, L.Y. Effect of different pretreatment techniques on quality characteristics, chemical composition, antioxidant capacity and flavor of cold-pressed rapeseed oil. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 201, 116157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.L.; Geng, S.; Liu, B.G. Characterization of Wei Safflower Seed Oil Using Cold-Pressing and Solvent Extraction. Foods 2023, 12, 3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.L.; Gao, P.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.Y.; Yin, J.J.; Zhong, W.; Reaney, M.J.T. Comparative Analysis of Frying Performance: Assessing Stability, Nutritional Value, and Safety of High-Oleic Rapeseed Oils. Foods 2024, 13, 2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wei, S.; Li, J.; Tang, S.; Xu, W. Phospholipid Content in Olive Oil. Mod. Food 2022, 28, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, A.; Moslehishad, M.; Ghanavi, Z. Physicochemical characteristics of Moringa peregrina seeds and oil obtained by solvent and cold-press extraction. Grasas Aceites 2024, 75, e570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 5525-2008; Vegetable Fats and Oils—Method for Identification of Transparency, Odor and Flavor. National Standard of the People’s Republic of China, General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2008.

- LS/T 3258-2018; Idesia polycarpa oil. National Grain Industry Standard of the People’s Republic of China, State Administration of Grain and Strategic Reserves: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Feng, H.X. Analysis of the Evolution Law and Structural Characteristics of Polar Compounds During the Frying Process of Soybean Oil. Ph.D. Thesis, Northeast Agricultural University, Harbin, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, N.; Ghavami, M.; Rashidi, L.; Gharachorloo, M.; Nateghi, L. Effects of adding green tea extract on the oxidative stability and shelf life of sunflower oil during storage. Food Chem. X 2024, 21, 101168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Leonardis, A.; Macciola, V. Heat-oxidation stability of palm oil blended with extra virgin olive oil. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 1769–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, K.; Chang, Y.; Song, M.; Liu, X.; He, J.; Ma, L. Analysis and evaluation of fruit composition and fatty acid compositionofldesia polycarpa Maxim from Different Geographic Regions. China Oils Fats 2025, 50, 129–134+152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, R.; Zhang, Y.R.; Zhang, H.; Jin, Q.Z.; Wu, G.C.; Wang, X.G. Effect of different processing methods on physicochemical properties, chemical compositions and in vitro antioxidant activities of Paeonia lactiflora Pall seed oils. Food Chem. 2020, 332, 127408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muangrat, R.; Chalermchat, Y.; Pannasai, S.; Osiriphun, S. Effect of Roasting and Vacuum Microwave Treatments on Physicochemical and Antioxidant Properties of Oil Extracted from Black Sesame Seeds. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. 2020, 8, 798–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, P.; Kuipers, N.J.M.; Haan, A.B.D. Hydraulic pressing of oilseeds: Experimental determination and modeling of yield and pressing rates. J. Food Eng. 2008, 89, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koubaa, M.; Mhemdi, H.; Vorobiev, E. Influence of canola seed dehulling on the oil recovery by cold pressing and supercritical CO2 extraction. J. Food Eng. 2016, 182, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, N.N.; Sun, W.H.; Li, D.; Wang, L.J.; Wang, Y. Effect of microwave-assisted hot air drying on drying kinetics, water migration, dielectric properties, and microstructure of corn. Food Chem. 2024, 455, 139913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, Z.; LI, W.; Lin, C. Effect of phospholipid content on smoke point, cold tolerance, oxidation stability and frying stability of frying oil. China Oils Fats 2019, 44, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Frangipane, M.T.; Cecchini, M.; Monarca, D.; Massantini, R. Effects of filtration processes on the quality of extra-virgin olive oil-literature update. Foods 2023, 12, 2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeur, H.; Zribi, A.; Bouaziz, M. Changes in chemical and sensory characteristics of Chemlali extra-virgin olive oil as depending on filtration. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2017, 119, 1500602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Bi, Y.; Xiao, X.; Yang, G.; Cao, D. Study on quality change of edible oil during frying. China Oils Fats 2006, 31, 34–36. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G.Y.; Liu, L.L.; Peng, F.L.; Ma, Y.C.; Deng, Z.Y.; Li, H.Y. Natural antioxidants enhance the oxidation stability of blended oils enriched in unsaturated fatty acids. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 2907–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wu, F.; Pan, J.; Hu, F. Changes in the quality of flaxseed oil during frying. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2022, 43, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, Y.; Dong, J.; He, X.M.; Wang, J.P.; Li, C.M.; Dong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.F.; Wang, H.X.; Yi, Y.; et al. Impact of Heating Temperature and Fatty Acid Type on the Formation of Lipid Oxidation Products During Thermal Processing. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 913297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, P.K.; Dash, U.; Rayaguru, K.; Krishnan, K.R. Physio-Chemical Changes During Repeated Frying of Cooked Oil: A Review. J. Food Biochem. 2016, 40, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.Z.; Zhang, X.P.; Qu, Z.H.; Gao, Y.; Li, Q.; Yu, X.Z. Mechanism, indexes, methods, challenges, and perspectives of edible oil oxidation analysis. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 4901–4915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahidi, F.; Wanasundara, U.N. 19 Methods for Measuring Oxidative Rancidity in Fats and Oils. In Food Lipids; Methods of Measuring Oxidative Rancidity in Fats and Oils; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannou, E.T.; Gliatis, K.S.; Zoidis, E.; Georgiou, C.A. Olive Oil Benefits from Sesame Oil Blending While Extra Virgin Olive Oil Resists Oxidation during Deep Frying. Molecules 2023, 28, 4290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H. Quality Change and Control of Camellia Seed Oil During High Temperature Heating. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University of Technology, Hangzhou, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.X.; Liu, M.C.; Lyu, C.; Li, B.; Meng, X.J.; Si, X.; Shu, C. Effect of Heat Treatment on Oxidation of Hazelnut Oil. J. Oleo Sci. 2022, 71, 1711–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, A.K.; Chauhan, O.P.; Roopa, N.; Padmashree, A.; Manjunatha, S.S.; Semwal, A.D. Effect of vacuum and atmospheric frying and heating on physicochemical properties of rice bran oil. J. Food Sci. Technol.-Mysore 2022, 59, 3428–3439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juncos, N.S.; Cravero, C.F.; Grosso, N.R.; Olmedo, R.H. Integral oxidation Value used as a new oxidation indicator for evaluation of advanced stages of oxidative processes: Intox value. Microchem. J. 2024, 204, 111186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.S.; Ali, M.A.; Muhammad, I.I.; Othman, N.H.; Noor, A.M. The Effect of Microwave Roasting Over the Thermo-oxidative Degradation of Perah Seed Oil During Heating. J. Oleo Sci. 2018, 67, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.S.; Labella, F.S. Comparison of analytical methods for monitoring autoxidation profiles of authentic lipids. J. Lipid Res. 1987, 28, 1110–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelqvist, L.Å.; Kamal-Eldin, A. Sesame oil and its mixtures are exceptions to AOCS method Cd 7-58. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1991, 68, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poiana, M.A. Enhancing Oxidative Stability of Sunflower Oil during Convective and Microwave Heating Using Grape Seed Extract. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 9240–9259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukesová, D.; Dostálová, J.; Mahmoud, E.E.M.; Svárovská, M. Oxidation Changes of Vegetable Oils during Microwave Heating. Czech J. Food Sci. 2009, 27, S178–S181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanibal, E.A.A.; Mancini, J. Frying oil and fat quality measured by chemical, physical, and test kit analyses. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2004, 81, 847–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kmiecik, D.; Fedko, M.; Malecka, J.; Siger, A.; Kowalczewski, P.L. Effect of Heating Temperature of High-Quality Arbequina, Picual, Manzanilla and Cornicabra Olive Oils on Changes in Nutritional Indices of Lipid, Tocopherol Content and Triacylglycerol Polymerization Process. Molecules 2023, 28, 4247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedko, M.; Kmiecik, D.; Siger, A.; Majcher, M. The Stability of Refined Rapeseed Oil Fortified by Cold-Pressed and Essential Black Cumin Oils under a Heating Treatment. Molecules 2022, 27, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivey, K.L.; Nguyen, X.M.T.; Li, R.F.; Furtado, J.; Cho, K.L.Y.; Gaziano, J.M.; Hu, F.B.; Willett, W.C.; Wilson, P.W.; Djoussé, L. Association of dietary fatty acids with the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in a prospective cohort of United States veterans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 118, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, R.L.; Sébédio, J.-L. Characterization of γ-linolenic acid geometrical isomers in borage oil subjected to heat treatments (deodorization). J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1994, 71, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.L.; Wang, J.Y.; Wang, X.R.; Gan, S.R.; Yang, F.R.; Dong, G.X. Assessing the influence of Secoisolariciresinol diglucoside multi-antioxidants on flaxseed oil’s oxidative stability. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2024, 126, 2300159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Number | Drying Methods | Impurity Contents/% | Filtration Cycles/Times |

|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | MVD | 0 | 1 |

| D2 | MD | 0 | 1 |

| D3 | FIOD | 0 | 1 |

| D4 | ASHPD | 0 | 1 |

| I1 | MVD | 0 | 1 |

| I2 | MVD | 10 | 1 |

| I3 | MVD | 20 | 1 |

| F1 | MVD | 0 | 1 |

| F2 | MVD | 0 | 3 |

| F3 | MVD | 0 | 5 |

| Index | MVD | MD | FIOD | ASHPD | LS/T 3258-2018 Idesia polycarpa Oil |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transparency (20 °C) | Slightly turbid | Slightly turbid | Turbid | Slightly turbid | Clear, transparent |

| Smell, taste | I. polycarpa oil flavor | I. polycarpa oil flavor | Smell of burning | Smell of burning | I. polycarpa oil flavor |

| L* (Lightness value) | 58.42 ± 0.01 a | 57.75 ± 0.04 b | 53.23 ± 0.04 d | 53.74 ± 0.04 c | — |

| a* (Red/Green value) | 48.91 ± 0.02 c | 52.1 ± 0.01 d | 55.83 ± 0.03 b | 57.47 ± 0.01 a | — |

| b* (Yellow/Blue value) | 100.22 ± 0.10 a | 98.97 ± 0.12 b | 91.41 ± 0.11 d | 92.33 ± 0.16 c | — |

| Moisture and Volatiles content (%) | 0.04 ± 0.02 c | 0.06 ± 0.02 bc | 0.07 ± 0.01 b | 0.10 ± 0.01 a | ≤0.1 |

| Insoluble impurities (%) | 0.02 ± 0.00 c | 0.09 ± 0.00 a | 0 ± 0.00 d | 0.03 ± 0.00 b | ≤0.05 |

| Acid value (mg KOH/100 g) | 1.19 ± 0.02 c | 1.45 ± 0.04 c | 4.61 ± 0.04 a | 3.52 ± 0.07 b | ≤3 |

| Peroxide value (meq/kg) | 15.76 ± 0.00 c | 10.24 ± 0.00 d | 23.64 ± 0.00 a | 22.06 ± 0.00 b | — |

| Phospholipid content (mg/g) | 0.97 ± 0.05 c | 1.30 ± 0.03 c | 4.36 ± 0.38 a | 2.83 ± 0.58 b | — |

| Smoke point (°C) | 201 ± 1.00 a | 197 ± 1.00 b | 177.67 ± 1.53 d | 181 ± 1.00 c | — |

| Index | IC0% | IC10% | IC20% | LS/T 3258-2018 Idesia polycarpa Oil |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transparency (20 °C) | Slightly turbid | Slightly turbid | Slightly turbid | Clear, transparent |

| Smell, taste | I. polycarpa oil flavor | I. polycarpa oil flavor | I. polycarpa oil flavor | I. polycarpa oil flavor |

| L* (Lightness value) | 58.42 ± 0.0115 a | 58.15 ± 0.0265 b | 55.82 ± 0.0058 c | — |

| a* (Red/Green value) | 52.1 ± 0.01 a | 50.33 ± 0 b | 48.32 ± 0.0058 c | — |

| b* (Yellow/Blue value) | 100.22 ± 0.101 a | 99.69 ± 0.0361 b | 95.75 ± 0.1026 c | — |

| Moisture and volatiles content (%) | 0.04 ± 0.02 b | 0.1 ± 0.03 a | 0.11 ± 0.01 a | ≤0.1 |

| Insoluble impurities (%) | 0.02 ± 0.00 a | 0.02 ± 0.01 b | 0.02 ± 0.00 a | ≤0.05 |

| Acid value (mg KOH/100 g) | 1.19 ± 0.02 c | 1.21 ± 0.02 b | 1.62 ± 0.00 a | ≤3 |

| Peroxide value (meq/kg) | 15.76 ± 0.00 b | 14.97 ± 0.00 c | 16.55 ± 0.00 a | — |

| Phospholipid content (mg/g) | 0.97 ± 0.05 b | 1.2 ± 0.08 a | 1.17 ± 0.00 a | — |

| Smoke point (°C) | 201.00 ± 1.00 a | 200.00 ± 1.00 a | 202.00 ± 1.00 a | — |

| Index | FC1 | FC3 | FC5 | LS/T 3258-2018 Idesia polycarpa Oil |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transparency (20 °C) | Slightly turbid | Slightly turbid | Clear, transparent | Clear, transparent |

| Smell, taste | I. polycarpa oil flavor | I. polycarpa oil flavor | I. polycarpa oil flavor | I. polycarpa oil flavor |

| L* (Lightness value)) | 58.42 ± 0.0115 c | 60.11 ± 0.0115 a | 59.58 ± 0.0173 b | — |

| a* (Red/Green value) | 52.1 ± 0.01 c | 52.81 ± 0.0058 b | 53.21 ± 0.0115 a | — |

| b* (Yellow/Blue value) | 100.22 ± 0.1012 c | 103.01 ± 0.0889 a | 102.24 ± 0.0896 b | — |

| Moisture and volatiles content (%) | 0.04 ± 0.02 b | 0.07 ± 0.00 a | 0.11 ± 0.03 a | ≤0.1 |

| Insoluble impurities (%) | 0.02 ± 0.00 a | 0.02 ± 0.00 a | 0 ± 0.00 b | ≤0.05 |

| Acid value (mg KOH/100 g) | 1.19 ± 0.02 b | 1.26 ± 0.06 a | 1.25 ± 0.04 a | ≤3 |

| Peroxide value (meq/kg) | 15.76 ± 0.00 a | 11.03 ± 0.02 b | 11.03 ± 0.0 b | — |

| Phospholipid content (mg/g) | 0.97 ± 0.05 b | 1.1 ± 0.03 a | 1.07 ± 0.00 a | — |

| Smoke point (°C) | 201.00 ± 1.00 a | 197.00 ± 1.00 b | 196.67 ± 0.58 b | — |

| Fatty Acid | IPVO | IPRO | SO | RO | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unh. | 180 °C | 200 °C | 220 °C | Unh. | 180 °C | 200 °C | 220 °C | Unh. | 180 °C | 200 °C | 220 °C | Unh. | 180 °C | 200 °C | 220 °C | |

| C16:0 | 15.54 | 15.50 | 15.61 | 15.74 | 15.37 | 15.82 | 15.74 | 15.87 | 10.67 | 11.04 | 11.12 | 11.51 | 4.49 | 4.56 | 4.57 | 4.69 |

| C16:1 | 5.14 | 5.14 | 5.18 | 5.21 | 5.14 | 5.26 | 5.61 | 5.87 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| C18:0 | 2.01 | 2.05 | 2.05 | 2.09 | 1.88 | 1.98 | 2.31 | 3.05 | 3.88 | 4.07 | 4.08 | 4.23 | 2.07 | 2.17 | 2.32 | 2.23 |

| C18:1 | 6.36 | 6.49 | 6.55 | 6.60 | 6.42 | 6.63 | 7.08 | 6.63 | 27.76 | 28.79 | 28.92 | 29.83 | 57.80 | 59.96 | 59.90 | 61.33 |

| C18:2 | 69.23 | 69.23 | 69.22 | 68.67 | 69.39 | 68.80 | 67.55 | 66.22 | 51.80 | 50.43 | 50.46 | 49.90 | 19.12 | 17.71 | 17.63 | 17.79 |

| C18:3 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.80 | 0.66 | 0.90 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.73 | 5.86 | 5.35 | 5.04 | 3.69 | 8.33 | 7.31 | 6.86 | 5.46 |

| C22:1 | 0.94 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.62 | 0.59 | 0.52 | 0.56 | — | — | — | — | 8.20 | 8.29 | 8.72 | 8.51 |

| t-C18:1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.16 | — | — | — | 0.21 |

| t-C18:2 | — | — | 0.17 | 0.60 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.28 | 0.77 | 0.01 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 0.67 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.24 |

| t-C18:3 | — | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 | — | — | 0.19 | 0.25 |

| ΣSFA | 17.55 | 17.55 | 17.66 | 17.83 | 17.25 | 17.80 | 18.05 | 18.92 | 14.58 | 15.11 | 15.19 | 15.74 | 6.56 | 6.73 | 6.89 | 6.92 |

| ΣMUFA | 12.44 | 12.06 | 12.15 | 12.25 | 12.18 | 12.49 | 13.22 | 13.06 | 27.76 | 28.79 | 28.92 | 29.83 | 66.00 | 68.25 | 68.63 | 69.83 |

| ΣPUFA | 70.09 | 70.08 | 70.02 | 69.32 | 70.29 | 69.59 | 68.30 | 66.95 | 57.66 | 55.78 | 55.50 | 53.59 | 27.45 | 25.02 | 24.49 | 23.25 |

| ΣTFA | — | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.60 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.28 | 0.77 | 0.02 | 0.32 | 0.39 | 0.87 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.31 | 0.70 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, H.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Q.; Ye, W.; Zheng, S.; Hou, J.; Chang, Y. Pretreatment and Thermal Stability of Idesia polycarpa Virgin Oil. Foods 2025, 14, 4210. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244210

Feng H, Zhao Y, Li Q, Ye W, Zheng S, Hou J, Chang Y. Pretreatment and Thermal Stability of Idesia polycarpa Virgin Oil. Foods. 2025; 14(24):4210. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244210

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Hongxia, Yazhen Zhao, Qingya Li, Wenhui Ye, Shuwen Zheng, Juncai Hou, and Yunhe Chang. 2025. "Pretreatment and Thermal Stability of Idesia polycarpa Virgin Oil" Foods 14, no. 24: 4210. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244210

APA StyleFeng, H., Zhao, Y., Li, Q., Ye, W., Zheng, S., Hou, J., & Chang, Y. (2025). Pretreatment and Thermal Stability of Idesia polycarpa Virgin Oil. Foods, 14(24), 4210. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14244210