Antimicrobial Effects of Three Plant-Derived Phenolic Compounds and Their Potential Role in Strawberry Preservation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Strawberries, Strains, Mediums and Chemicals

2.2. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

2.3. Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index (FICI)

2.4. Growth Curve of E. coli

2.5. Spore Germination of B. cinerea, C. gloeosporioides and A. niger

2.6. Molecular Docking

2.7. Effects of EGCG, RES and TP on Infected Strawberries

2.7.1. Treatment of Strawberries

2.7.2. Hardness

2.7.3. Weight Loss

2.7.4. Color

2.8. Titratable Acid (TA) and Soluble Solids Content (SSC)

2.9. Sensory Evaluation

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

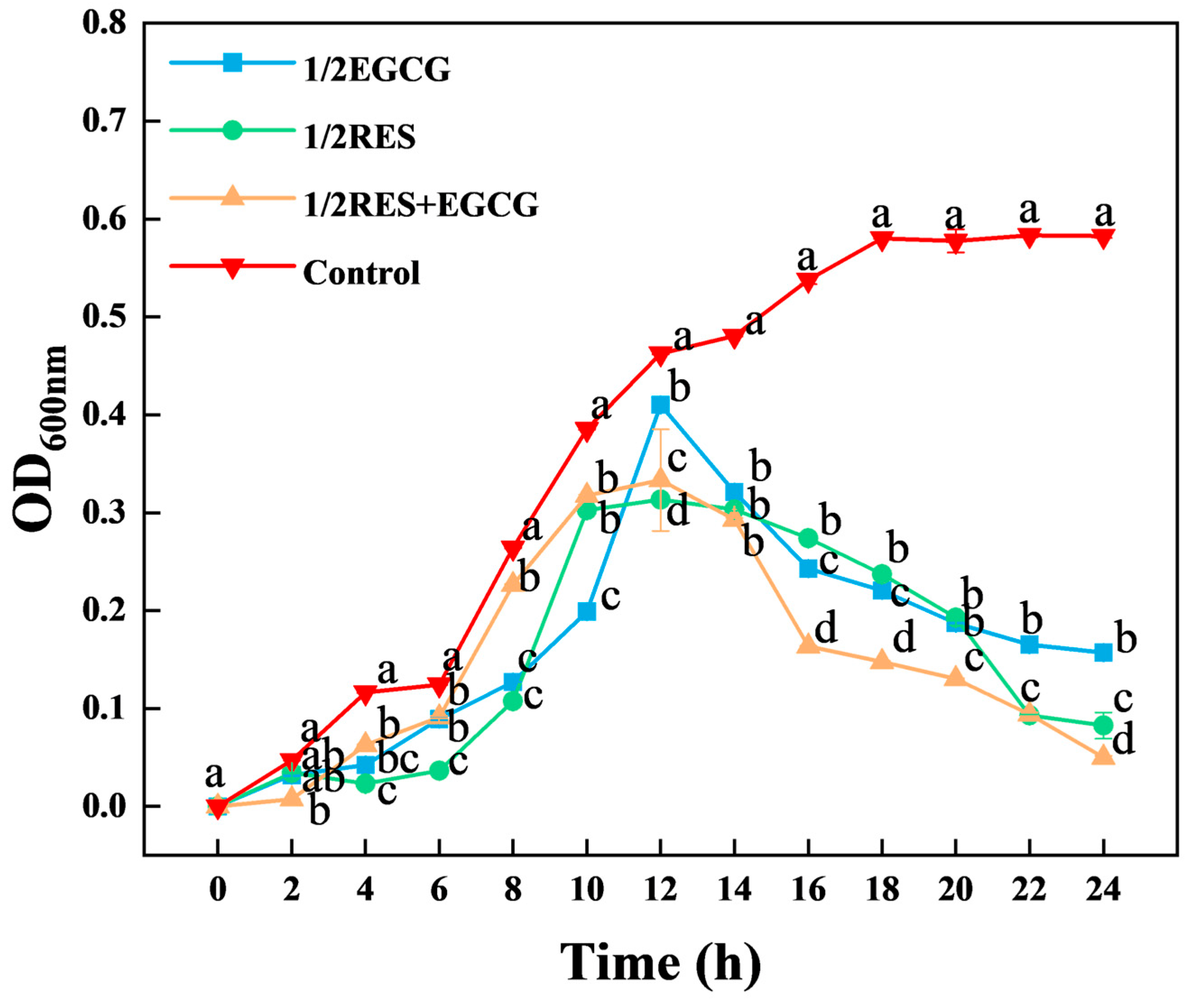

3.1. Resveratrol and Epigallocatechin Gallate Inhibited the Growth of E. coli

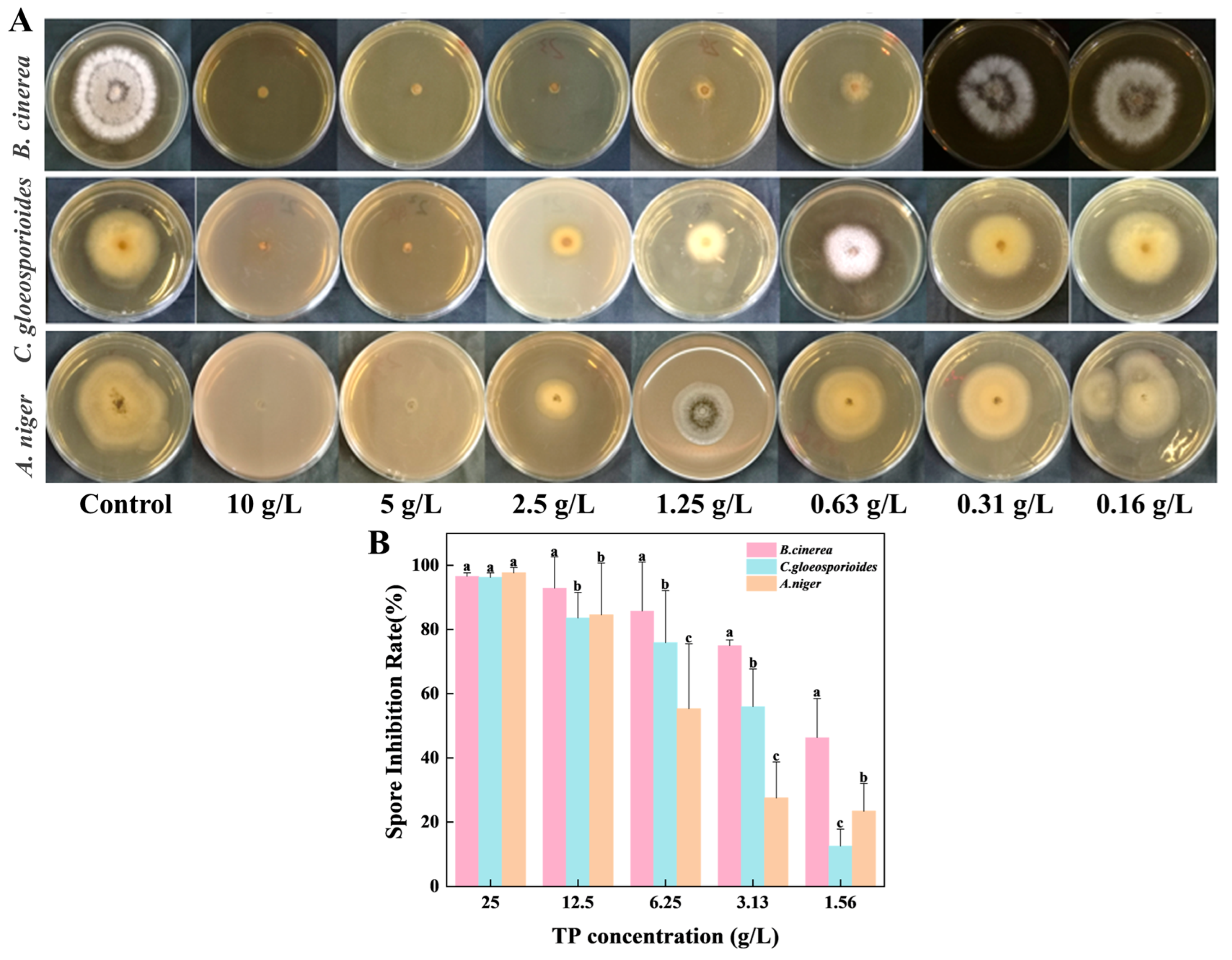

3.2. Tea Polyphenols Inhibited the Growth of Spoilage Fungus

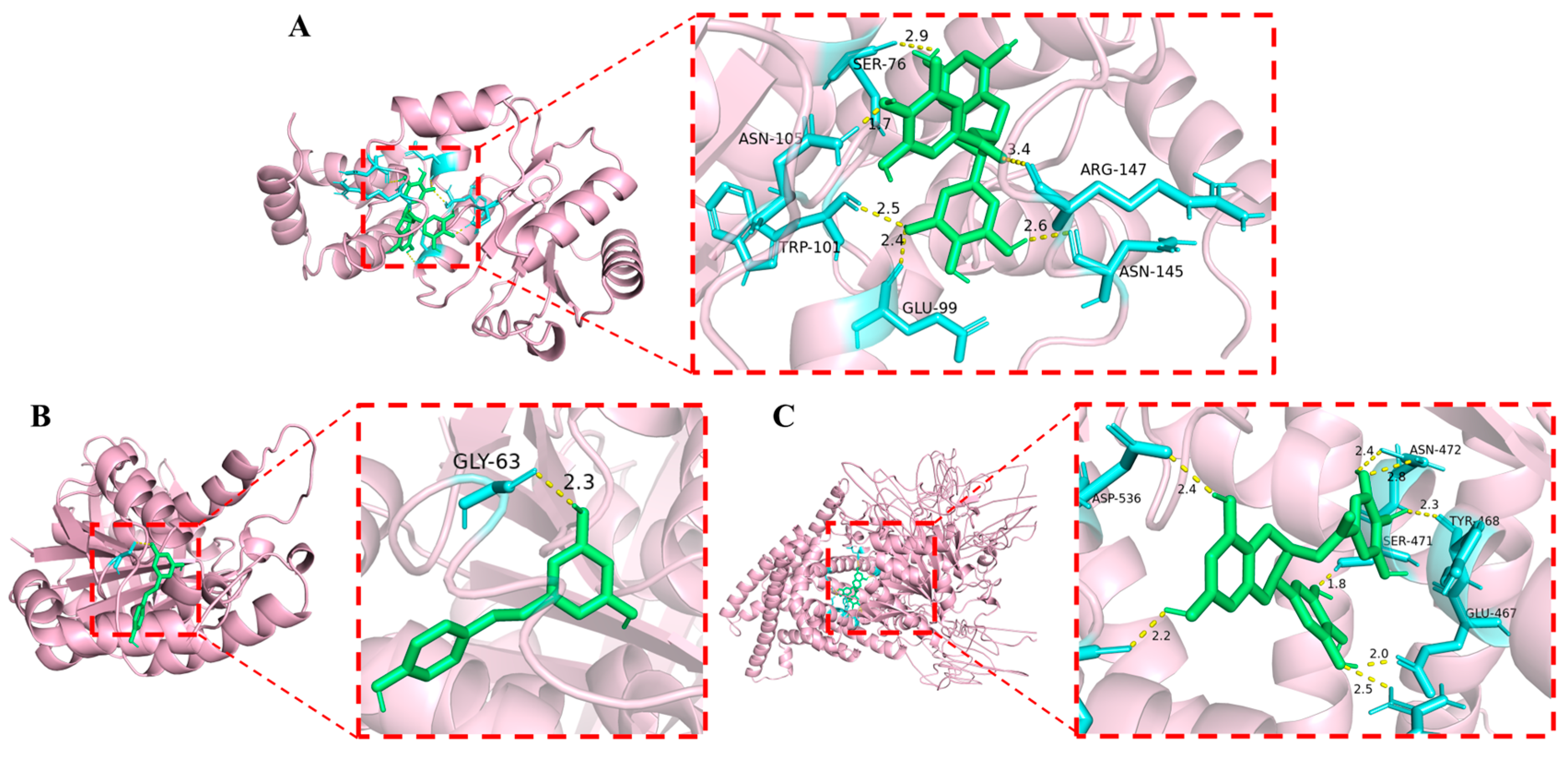

3.3. The Potential Targets of the Phenolic Compounds

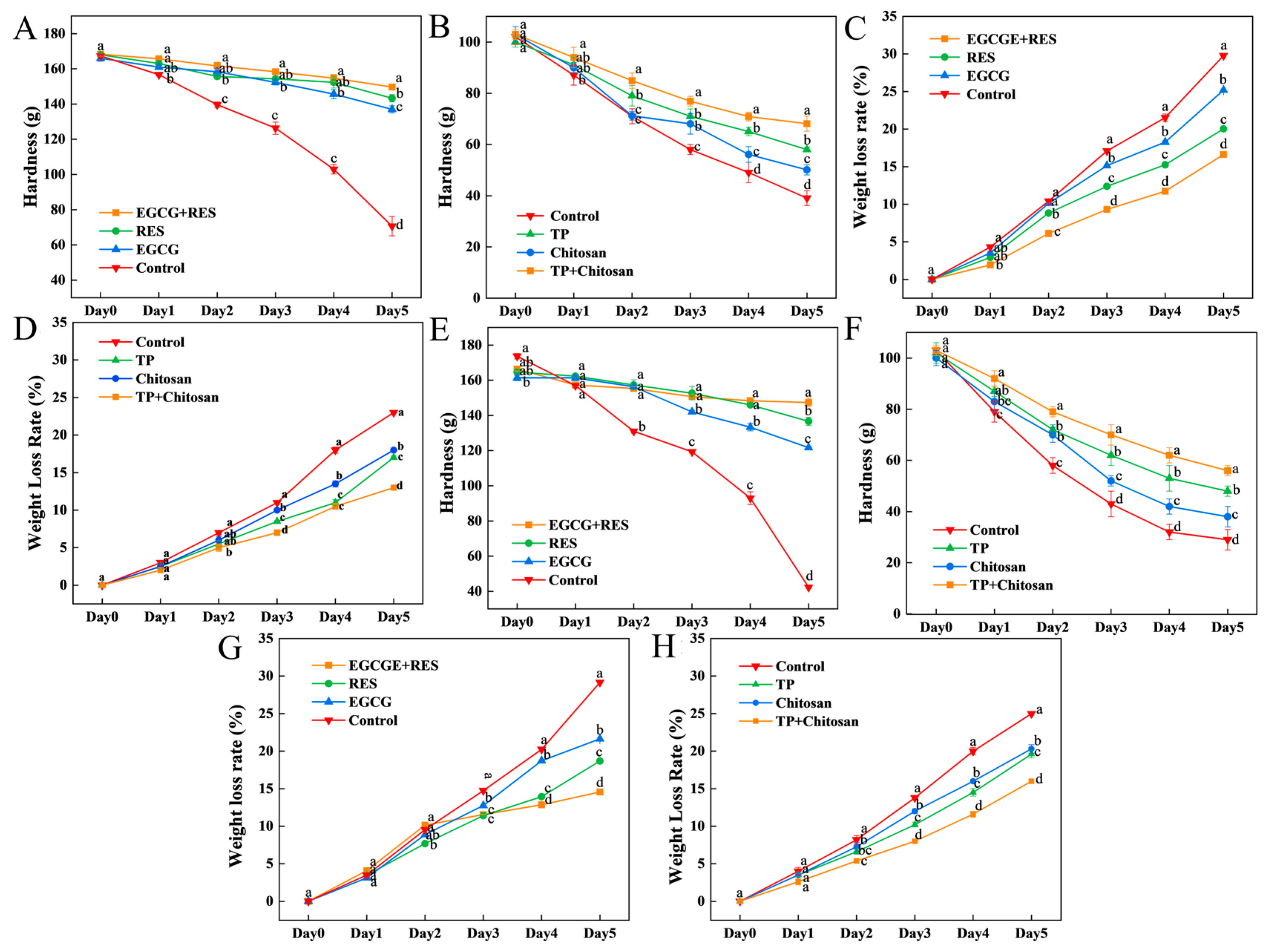

3.4. Epigallocatechin Gallate, Resveratrol, and Tea Polyphenols Maintained the Hardness and Weight of Strawberry

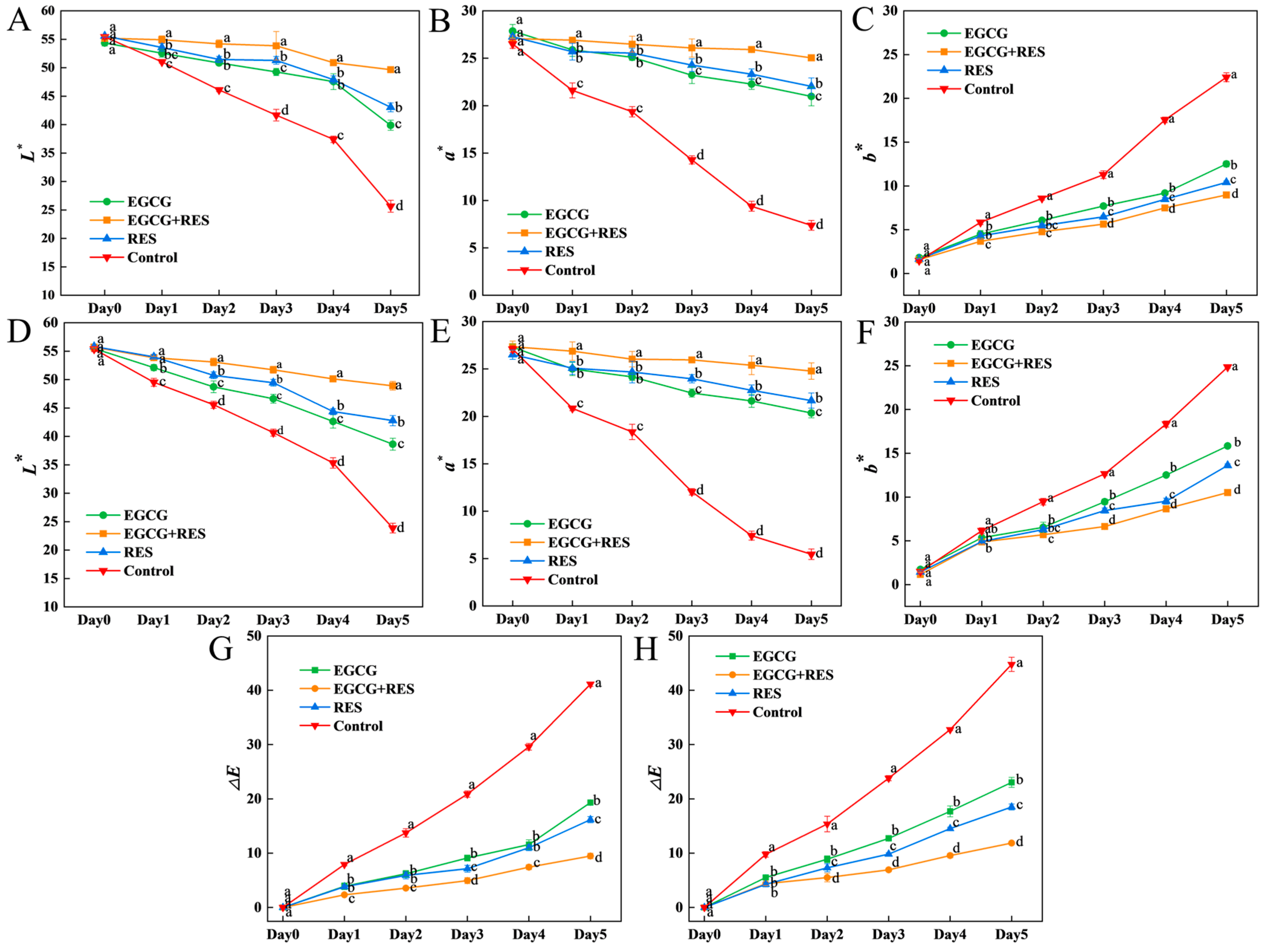

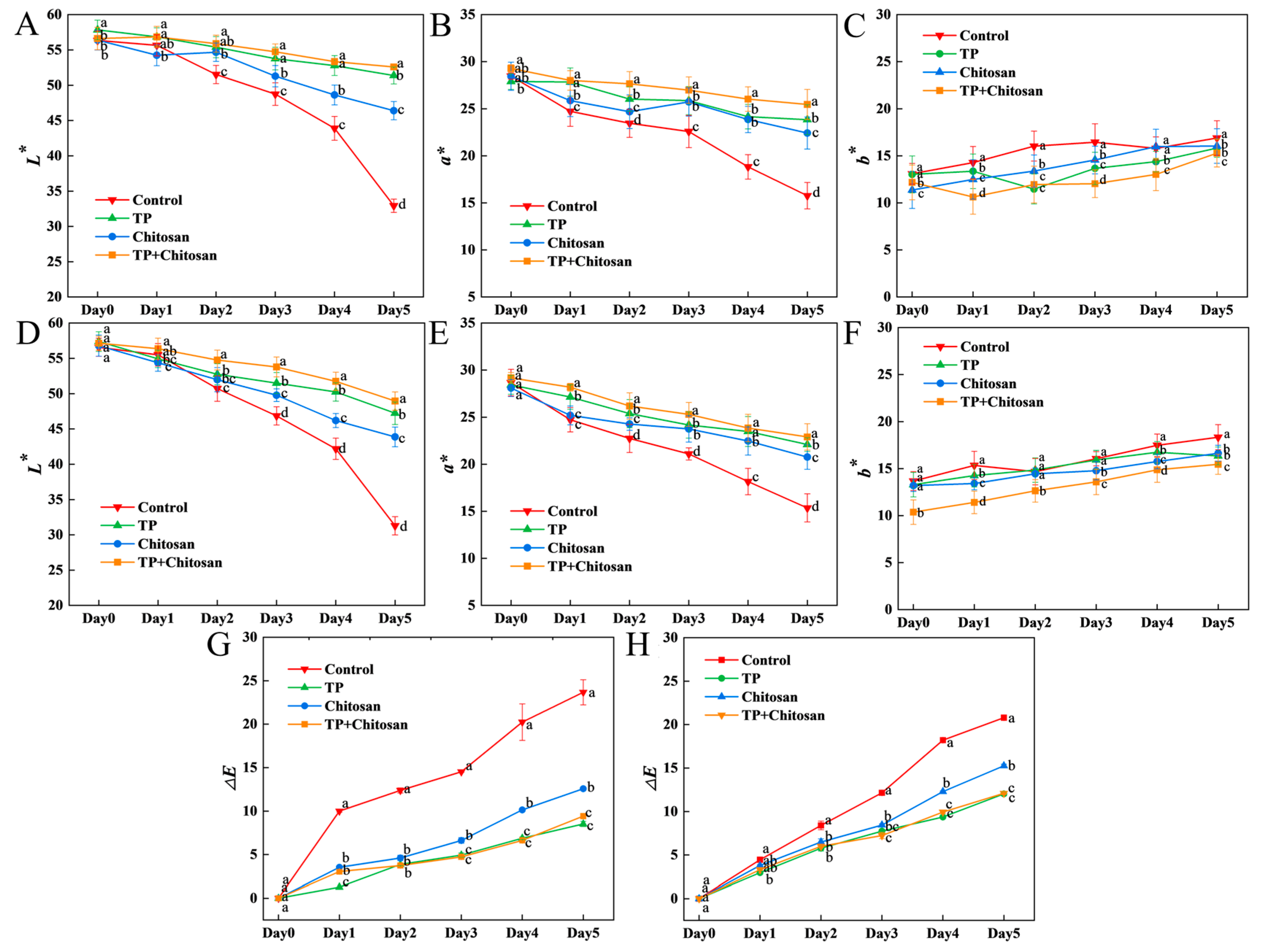

3.5. Epigallocatechin Gallate, Resveratrol, and Tea Polyphenols Preserved the Color of Strawberry

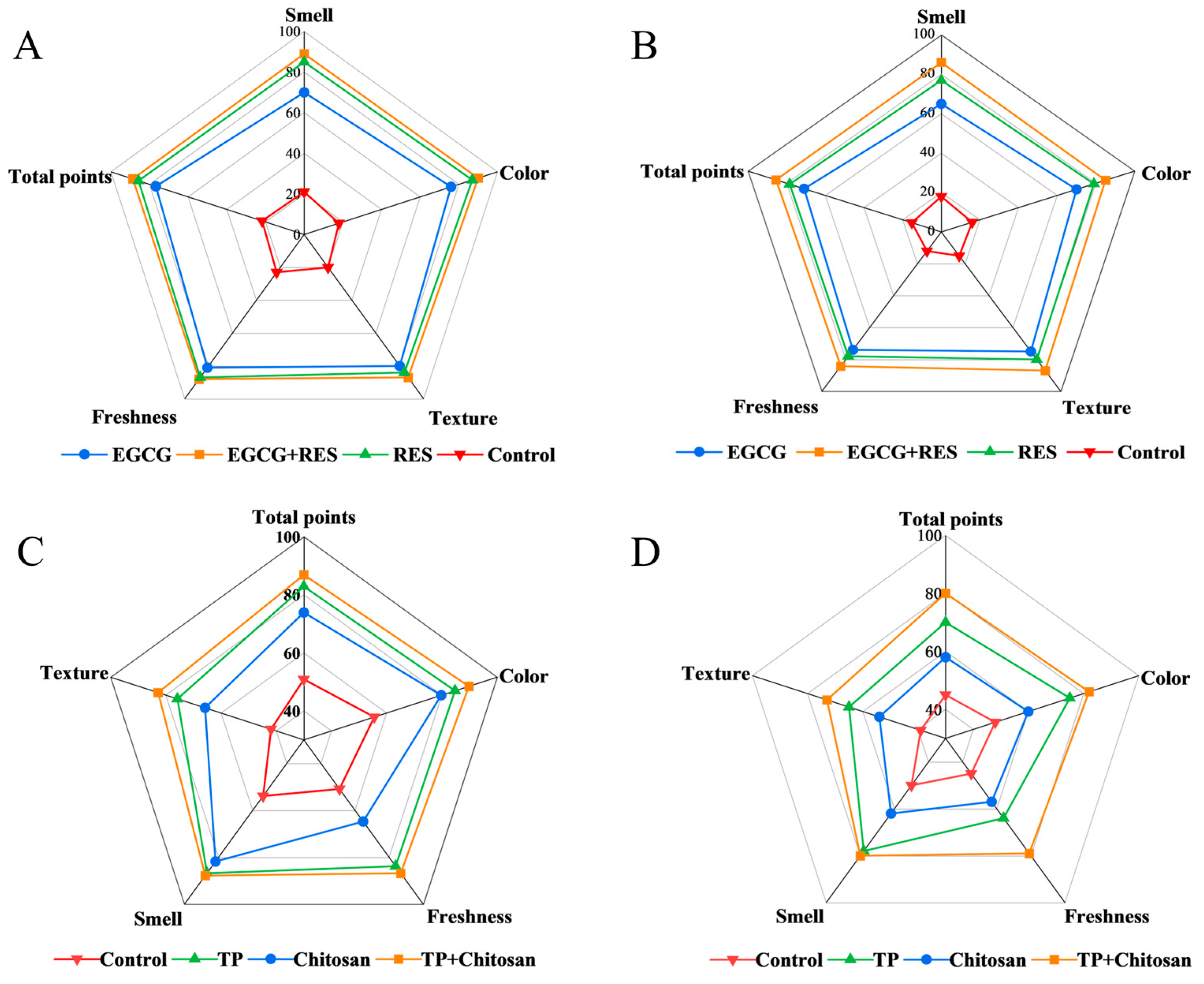

3.6. Epigallocatechin Gallate, Resveratrol, and Tea Polyphenols Elevated the Consumer Acceptance of Strawberries

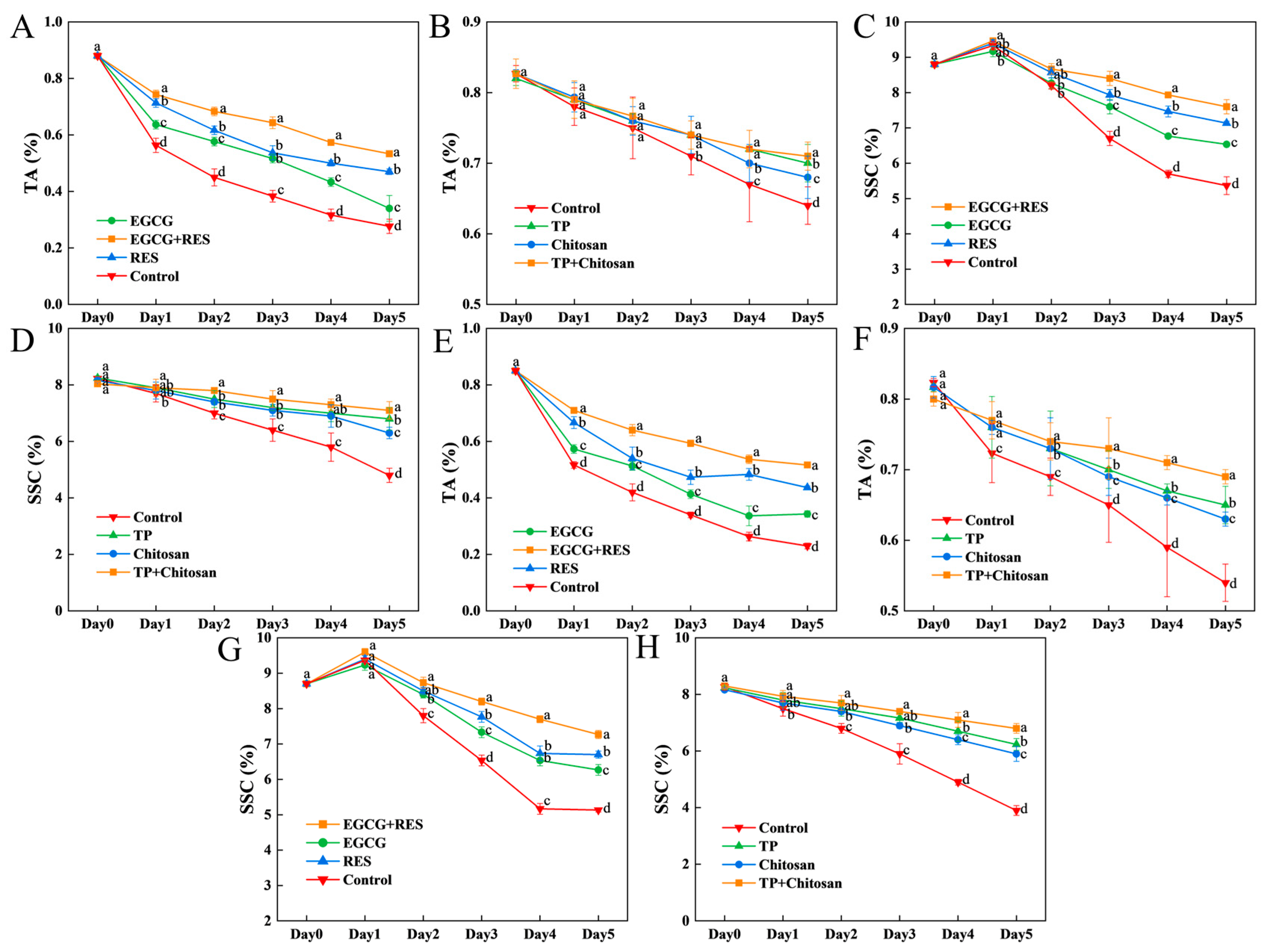

3.7. Epigallocatechin Gallate, Resveratrol, and Tea Polyphenols Enhanced the Flavor Quality of Strawberry

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hernández-Martínez, N.R.; Blanchard, C.; Wells, D.; Salazar-Gutiérrez, M.R. Current state and future perspectives of commercial strawberry production: A review. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 312, 111893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Li, X.; Gao, Q.-H.; Geng, C.; Duan, K. Colletotrichum species pathogenic to strawberry: Discovery history, global diversity, prevalence in China, and the host range of top two species. Phytopathol. Res. 2022, 4, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Azevedo, L.C.B.; Pandey, J.; Khusharia, S.; Kumari, M.; Kumar, D.; Kaushalendra; Bhardwaj, N.; Teotia, P.; Kumar, A. Microbial Intervention: An Approach to Combat the Postharvest Pathogens of Fruits. Plants 2022, 11, 3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbey, J.A.; Percival, D.; Abbey, L.; Asiedu, S.K.; Prithiviraj, B.; Schilder, A. Biofungicides as alternative to synthetic fungicide control of grey mould (Botrytis cinerea)—Prospects and challenges. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2018, 29, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Lu, J.-H.; Xu, M.-T.; Shi, X.-C.; Song, Z.-W.; Chen, T.-M.; Herrera-Balandrano, D.D.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Laborda, P.; Shahriar, M.; et al. Evaluation of chitosan coatings enriched with turmeric and green tea extracts on postharvest preservation of strawberries. Lwt 2022, 163, 113551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyaprom, S.; Mosoni, P.; Leroy, S.; Kaewkod, T.; Desvaux, M.; Tragoolpua, Y. Antioxidants of Fruit Extracts as Antimicrobial Agents against Pathogenic Bacteria. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.-H.; Chen, F.-H.; Yang, Y.-L.; Zhan, Y.-F.; Herman, R.A.; Gong, L.-C.; Sheng, S.; Wang, J. The Transcription Factor CsgD Contributes to Engineered Escherichia coli Resistance by Regulating Biofilm Formation and Stress Responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amil-Ruiz, F.; Blanco-Portales, R.; Muñoz-Blanco, J.; Caballero, J.L. The Strawberry Plant Defense Mechanism: A Molecular Review. Plant Cell Physiol. 2011, 52, 1873–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-García, J.R.; Leonardo-Elias, A.; Angoa-Pérez, M.V.; Villar-Luna, E.; Arias-Martínez, S.; Oyoque-Salcedo, G.; Oregel-Zamudio, E. Bacillus subtilis Edible Films for Strawberry Preservation: Antifungal Efficacy and Quality at Varied Temperatures. Foods 2024, 13, 980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrasch, S.; Knapp, S.J.; van Kan, J.A.L.; Blanco-Ulate, B. Grey mould of strawberry, a devastating disease caused by the ubiquitous necrotrophic fungal pathogen Botrytis cinerea. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2019, 20, 877–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yin, Y.; Affandi, F.Y.; Zhong, C.; Schouten, R.E.; Woltering, E.J. High CO2 Reduces Spoilage Caused by Botrytis cinerea in Strawberry Without Impairing Fruit Quality. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razavizadeh, B.M.; Shahrampour, D.; Niazmand, R. Investigating the effect of acoustic waves on spoilage fungal growth and shelf life of strawberry fruit. Fungal Biol. 2024, 128, 1705–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiao, J.; Guo, L.; Huo, J.; Huang, D.; Zhang, Y. Controlled atmosphere effects on postharvest quality and antioxidant capacity of blue honeysuckle (Lonicera caerulea L.). Food Innov. Adv. 2024, 3, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Ji, X.; Wu, J.; Wei, G.; Sun, X.; Wang, M.; Liu, W.; Cui, Z.; Xu, X.; Li, Y.; et al. Effects of light quality on physiological and biochemical attributes of ‘Queen Nina’ grape berries. Food Innov. Adv. 2025, 4, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, R.; Deng, Y.; Zheng, M.; Yu, S.; Nie, Y.; Li, J.-Q.; Pan, C.; Zhou, Z.; Diao, J. Insights into the Mechanism of Flavor Loss in Strawberries Induced by Two Fungicides Integrating Transcriptome and Metabolome Analysis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71, 3906–3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Miao, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, G. Characterization of Colletotrichum spp. Sensitivity to Carbendazim for Isolates Causing Strawberry Anthracnose in China. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Zeng, R.; Gao, S.; Xu, L.; Song, Z.; Dai, F. Resistance Profiles of Botrytis cinerea to Fluxapyroxad from Strawberry Fields in Shanghai, China. Plant Dis. 2023, 107, 2724–2728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raynaldo, F.A.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wu, B.; Li, D. Biological control and other alternatives to chemical fungicides in controlling postharvest disease of fruits caused by Alternaria alternata and Botrytis cinerea. Food Innov. Adv. 2024, 3, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Liu, J. Resveratrol: A review of plant sources, synthesis, stability, modification and food application. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 100, 1392–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latruffe, N.; Rifler, J.-P. Bioactive Polyphenols from Grapes and Wine Emphasized with Resveratrol. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 6053–6063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Lee, D.G. Resveratrol induces membrane and DNA disruption via pro-oxidant activity against Salmonella typhimurium. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 489, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sang, S.; Hou, Z.; Lambert, J.D.; Yang, C.S. Redox Properties of Tea Polyphenols and Related Biological Activities. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2005, 7, 1704–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capasso, L.; De Masi, L.; Sirignano, C.; Maresca, V.; Basile, A.; Nebbioso, A.; Rigano, D.; Bontempo, P. Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG): Pharmacological Properties, Biological Activities and Therapeutic Potential. Molecules 2025, 30, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y.-H.; Lee, J.-H.; Ahn, J.-S.; Nam, S.-H.; Oh, D.-K.; Park, D.-H.; Chung, H.-J.; Kang, S.; Day, D.F.; Kim, D. Synthesis, Structure Analyses, and Characterization of Novel Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG) Glycosides Using the Glucansucrase from Leuconostoc mesenteroides B-1299CB. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 1230–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.P.; Jiang, X.D.; Chen, J.J.; Zhang, S.S. Control of postharvest grey mould decay of nectarine by tea polyphenol combined with tea saponin. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 57, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; He, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, H.; Mei, X.; Zhao, J.; Du, Q.; Jin, P.; Xie, D. Enhanced antioxidant activity of low-molecular-weight hyaluronan-based coatings amended with EGCG for Torreya grandis kernels preservation. Food Chem. 2025, 478, 143742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Q.; Zhou, F.; Ly, N.K.; Ordyna, J.; Peterson, T.; Fan, Z.; Wang, S. Development of Multifunctional Nanoencapsulated trans-Resveratrol/Chitosan Nutraceutical Edible Coating for Strawberry Preservation. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 8586–8597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.J.; Middleton, R.F.; Westmacott, D. The fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) index as a measure of synergy. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1983, 11, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CLSI M07-ED12:2024 Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically, 12th ed.; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2024.

- Aouadi, G.; Grami, L.K.; Taibi, F.; Bouhlal, R.; Elkahoui, S.; Zaagueri, T.; Jallouli, S.; Chaanbi, M.; Hajlaoui, M.R.; Mediouni Ben Jemâa, J. Assessment of the efficiency of Mentha pulegium essential oil to suppress contamination of stored fruits by Botrytis cinerea. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2022, 129, 881–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadwa, A.O.; Albarag, A.M.; Alkoblan, D.K.; Mateen, A. Determination of synergistic effects of antibiotics and Zno NPs against isolated E. Coli and A. Baumannii bacterial strains from clinical samples. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 5332–5337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Lu, F.; Wang, X.; Liang, R.; Pu, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, D.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, X. Inhibitory effects of potassium sorbate and ZnO nanoparticles on Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus in milk-based beverage. Int. Dairy J. 2024, 159, 106073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuma, S.A.F.; Septyadi, R.; Sofian, F.F. Inhibition of bacillus spores germination by cinnamon bark, fingerroot, and moringa leaves extract. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2022, 13, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.J.; Corte, D.D. Using molecular docking and molecular dynamics to investigate protein-ligand interactions. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2021, 35, 2130002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Tan, W.; Feng, X.; Feng, K.; Hu, W. Application of Cinnamaldehyde Solid Lipid Nanoparticles in Strawberry Preservation. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Deng, X.; Guo, K.; Yin, X.; Zhang, C.; Yang, Y.; Xv, P.; Liu, L.; Rao, Y. Characterization of quorum quenching enzyme AiiA and its potential role in strawberry preservation. Food Res. Int. 2025, 207, 116059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidt, T.B.; Silva, F.V.M. High pressure processing and storage of blueberries: Effect on fruit hardness. High Press. Res. 2017, 38, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Jia, L.; Tao, H.; Hu, W.; Li, C.; Aziz, T.; Al-Asmari, F.; Sameeh, M.Y.; Cui, H.; Lin, L. Fortification of cassava starch edible films with Litsea cubeba essential oil for chicken meat preservation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 276, 133920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, H.; Stipkovits, F.; Wühl, J.; Halbwirth, H.; Gössinger, M. Strawberry Post-Harvest Anthocyanin Development to Improve the Colour Stability of Strawberry Nectars. Beverages 2024, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdipour, M.; Sadat Malekhossini, P.; Hosseinifarahi, M.; Radi, M. Integration of UV irradiation and chitosan coating: A powerful treatment for maintaining the postharvest quality of sweet cherry fruit. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 264, 109197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziedzic, E.; Błaszczyk, J. Evaluation of sweet cherry fruit quality after short-term storage in relation to the rootstock. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2019, 60, 925–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomadoni, B.; Moreira, M.R.; Pereda, M.; Ponce, A.G. Gellan-based coatings incorporated with natural antimicrobials in fresh-cut strawberries: Microbiological and sensory evaluation through refrigerated storage. Lwt 2018, 97, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.-G.; Chen, Y.-J.; Tong, J.-W.; Huang, J.-A.; Li, J.; Gong, Y.-S.; Liu, Z.-H. Tea polyphenol epigallocatechin gallate inhibits Escherichia coli by increasing endogenous oxidative stress. Food Chem. 2017, 217, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, D.; Lim, Y.-H. Resveratrol antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli is mediated by Z-ring formation inhibition via suppression of FtsZ expression. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skroza, D.; Šimat, V.; Smole Možina, S.; Katalinić, V.; Boban, N.; Generalić Mekinić, I. Interactions of resveratrol with other phenolics and activity against food-borne pathogens. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 2312–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Cui, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, B.; Xu, Y.; Tian, S.; Chen, T. Honokiol suppresses mycelial growth and reduces virulence of Botrytis cinerea by inducing autophagic activities and apoptosis. Food Microbiol. 2020, 88, 103411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Liu, K.; Fan, Y.; Cao, J.; Li, H.; Song, W.; Liu, Y.; Miao, M. Cell-free supernatant of Bacillus velezensis suppresses mycelial growth and reduces virulence of Botrytis cinerea by inducing oxidative stress. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 980022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Jiang, X. Antifungal activity and mechanism of tea polyphenols against Rhizopus stolonifer. Biotechnol. Lett. 2015, 37, 1463–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.M.; Guo, J.H.; Cheng, Y.J.; Liu, P.; Long, C.A.; Deng, B.X. Inhibitory activity of tea polyphenol and Hanseniaspora uvarum against Botrytis cinerea infections. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 51, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wang, B.; Cui, K.; Cao, J.; Jiang, W. Improving postharvest quality and antioxidant capacity of sweet cherry fruit by storage at near-freezing temperature. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 246, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, D.O.; Mika, F.; Richter, A.M.; Hengge, R. The green tea polyphenol EGCG inhibits E. coli biofilm formation by impairing amyloid curli fibre assembly and downregulating the biofilm regulator CsgD via the σE-dependent sRNA RybB. Mol. Microbiol. 2016, 101, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumar, V.C. The dynamics of Escherichia coli FtsZ dimer. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 43, 903–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choquer, M.; Boccara, M.; Gonçalves, I.R.; Soulié, M.C.; Vidal-Cros, A. Survey of the Botrytis cinerea chitin synthase multigenic family through the analysis of six euascomycetes genomes. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004, 271, 2153–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Jiao, Q.; Gao, J.; Luo, X.; Song, Y.; Li, T.; Huan, C.; Huang, M.; Ren, G.; Shen, Q.; et al. Effects of Zein-Lecithin-EGCG nanoparticle coatings on postharvest quality and shelf life of loquat (Eriobotrya japonica). Lwt 2023, 182, 114918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hua, Z.; Li, Y.; Chen, T.; Alamri, A.S.; Xu, Y.; Gong, W.; Hou, Y.; Alhomrani, M.; Hu, J. Development of multifunctional chitosan-based composite film loaded with tea polyphenol nanoparticles for strawberry preservation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 275, 133648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gardenal, A.C.; Leite, A.R.Z.; Cardoso, F.A.R.; Mello, J.C.P.; Marques, L.L.M.; Perdoncini, M. Strawberries treated with biodegradable film containing plant extracts. Braz. J. Biol. 2024, 84, e276874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernal-Mercado, A.T.; Ayala-Zavala, J.F.; Cruz-Valenzuela, M.R.; Gonzalez-Aguilar, G.A.; Nazzaro, F.; Fratianni, F.; Miranda, M.R.A.d.; Silva-Espinoza, B.A. Using Sensory Evaluation to Determine the Highest Acceptable Concentration of Mango Seed Extract as Antibacterial and Antioxidant Agent in Fresh-Cut Mango. Foods 2018, 7, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.-L.; Cui, Q.-L.; Wang, Y.; Shi, F.; Liu, Y.-P.; Liu, J.-L.; Nie, G.-W. Effect of carboxymethyl chitosan-gelatin-based edible coatings on the quality and antioxidant properties of sweet cherry during postharvest storage. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 289, 110462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, L.; Sun, H.; Zhou, Y.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, C. Enhancement of Antioxidant Property of N-Carboxymethyl Chitosan and Its Application in Strawberry Preservation. Molecules 2022, 27, 8496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.T.; Zhang, J.; Cao, J.X.; Xia, M.H.; Wang, T.; Cao, S. Effects of resveratrol treatment on quality and antioxidant properties of postharvest strawberry fruit. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liang, Z.; Li, S.; Zhang, L.; Wu, F.; Pu, S.; Liu, X.; Rao, Y. Antimicrobial Effects of Three Plant-Derived Phenolic Compounds and Their Potential Role in Strawberry Preservation. Foods 2025, 14, 4142. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234142

Liang Z, Li S, Zhang L, Wu F, Pu S, Liu X, Rao Y. Antimicrobial Effects of Three Plant-Derived Phenolic Compounds and Their Potential Role in Strawberry Preservation. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4142. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234142

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Ziwei, Shengshuai Li, Lanxi Zhang, Fengqin Wu, Shuyan Pu, Xinyue Liu, and Yu Rao. 2025. "Antimicrobial Effects of Three Plant-Derived Phenolic Compounds and Their Potential Role in Strawberry Preservation" Foods 14, no. 23: 4142. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234142

APA StyleLiang, Z., Li, S., Zhang, L., Wu, F., Pu, S., Liu, X., & Rao, Y. (2025). Antimicrobial Effects of Three Plant-Derived Phenolic Compounds and Their Potential Role in Strawberry Preservation. Foods, 14(23), 4142. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234142