Recent Developments on Salmonella and Listeria monocytogenes Detection Technologies: A Focus on Electrochemical Biosensing Technologies

Abstract

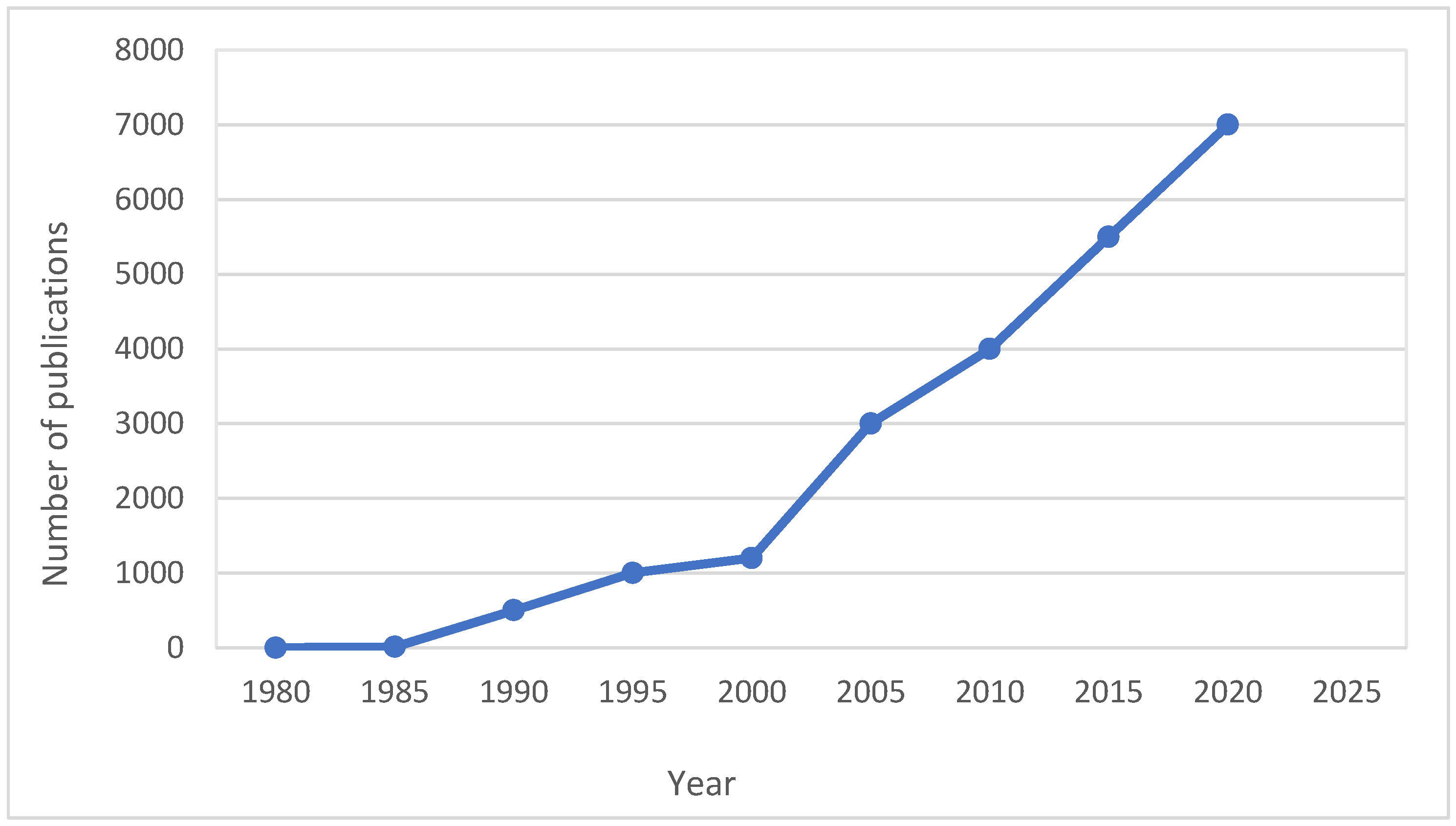

1. Introduction

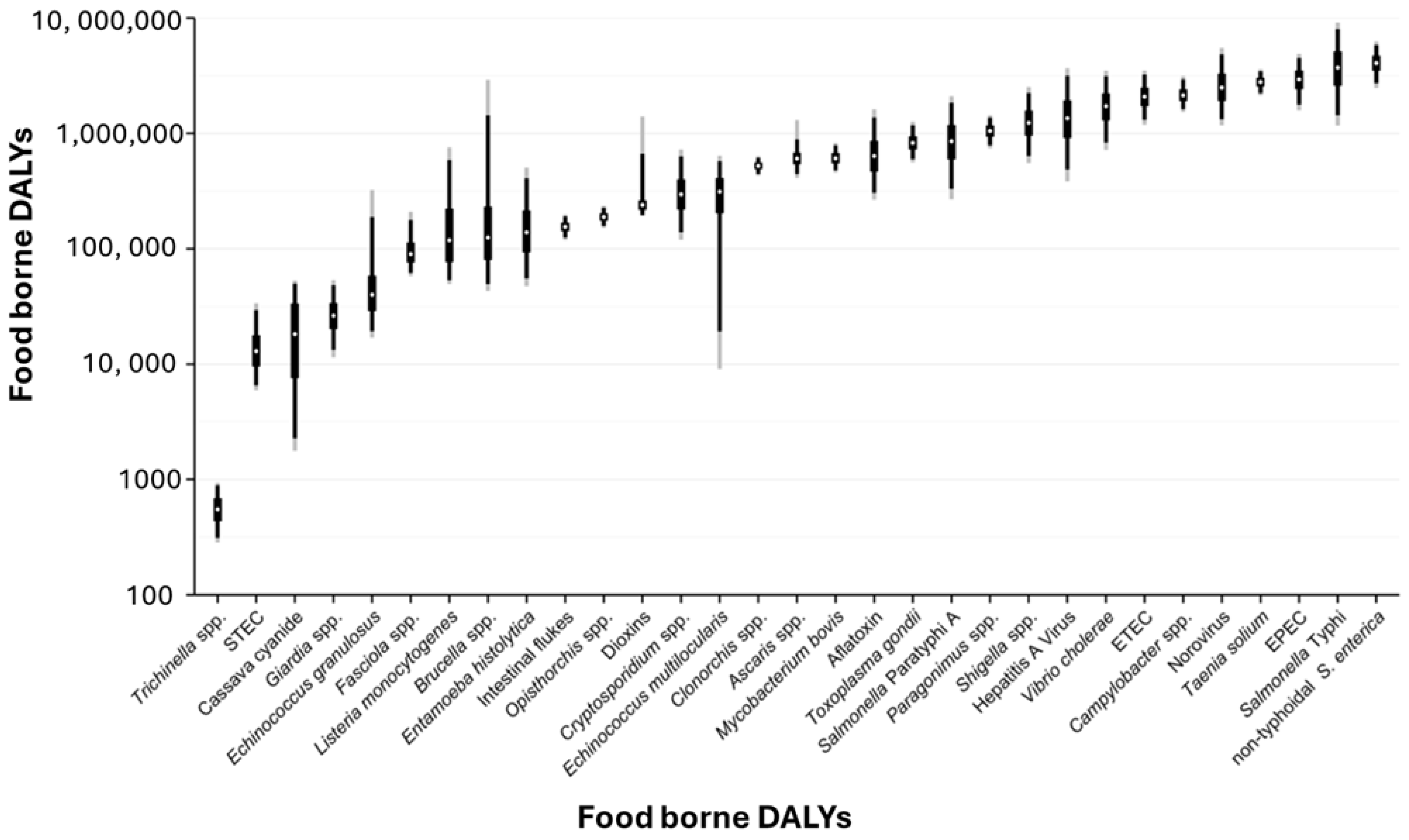

2. Overview of Foodborne Pathogens and Their Impact

2.1. Listeria Monocytogenes

2.2. Salmonella Species

3. Conventional Detection Methods of Foodborne Pathogens

3.1. Culture-Based Methods

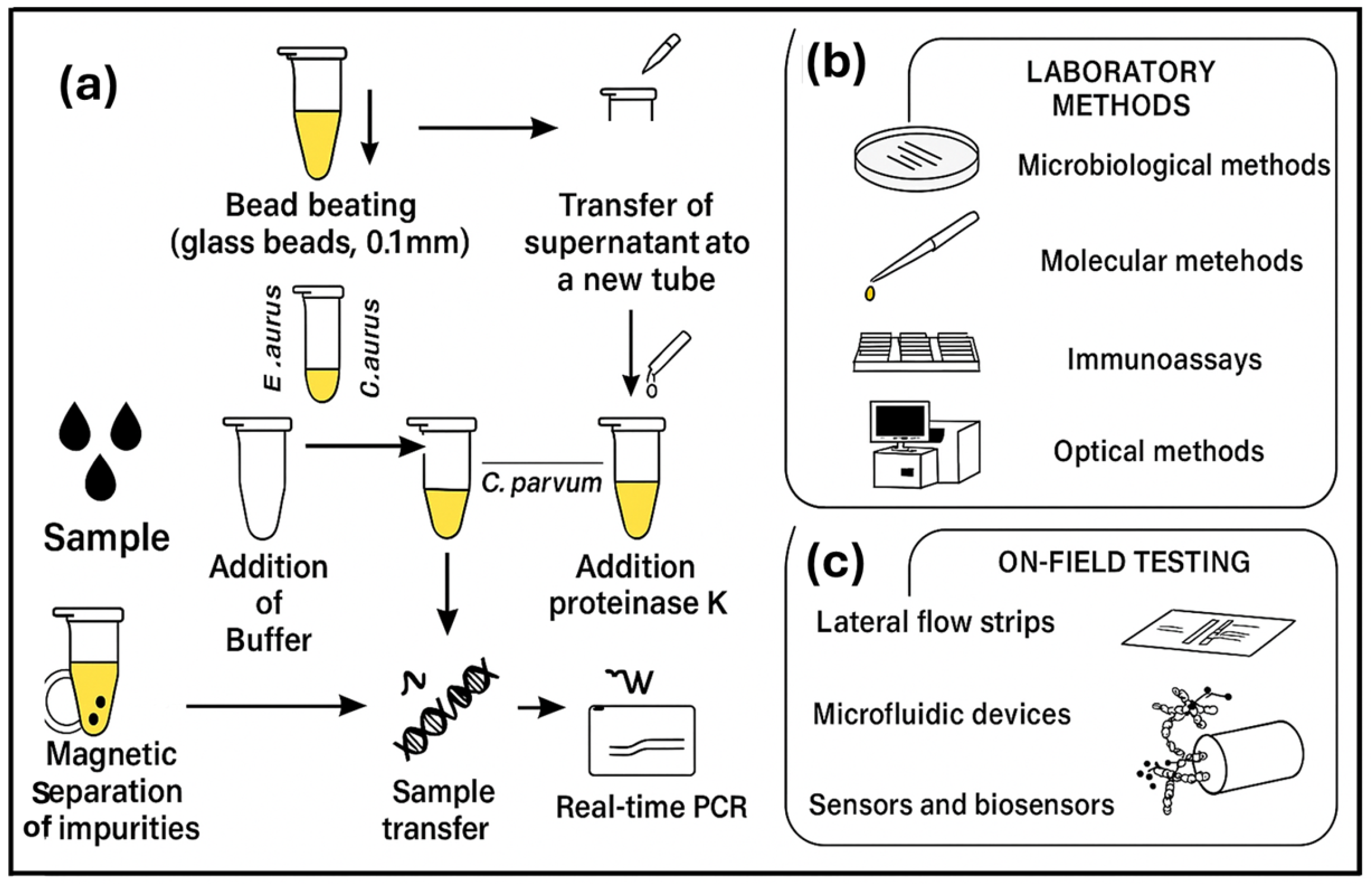

3.2. Culture-Independent Methods

3.3. Immunological-Based Assays

3.4. Spectroscopy-Based Methods

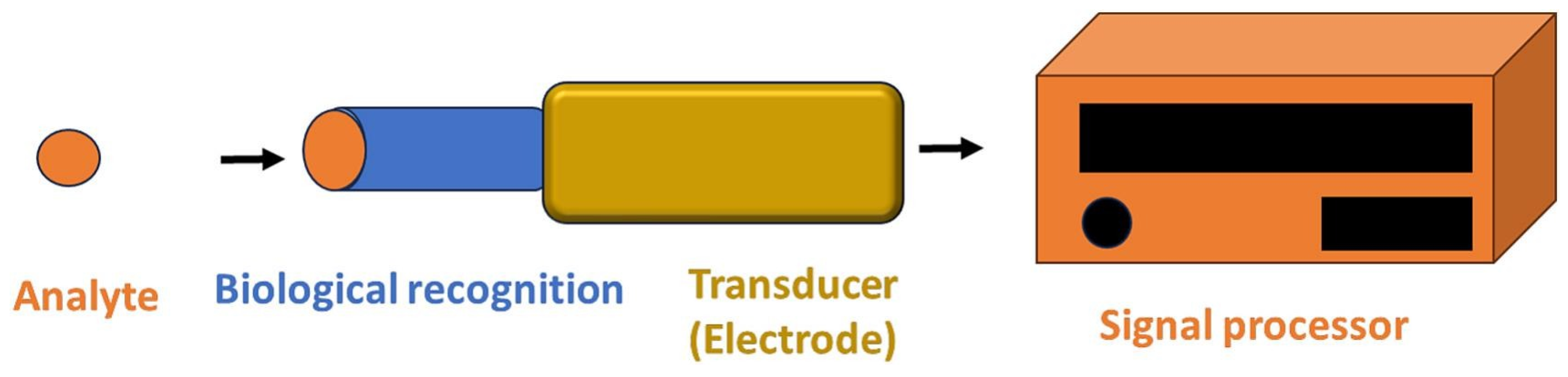

4. Biosensors for Pathogen Detection

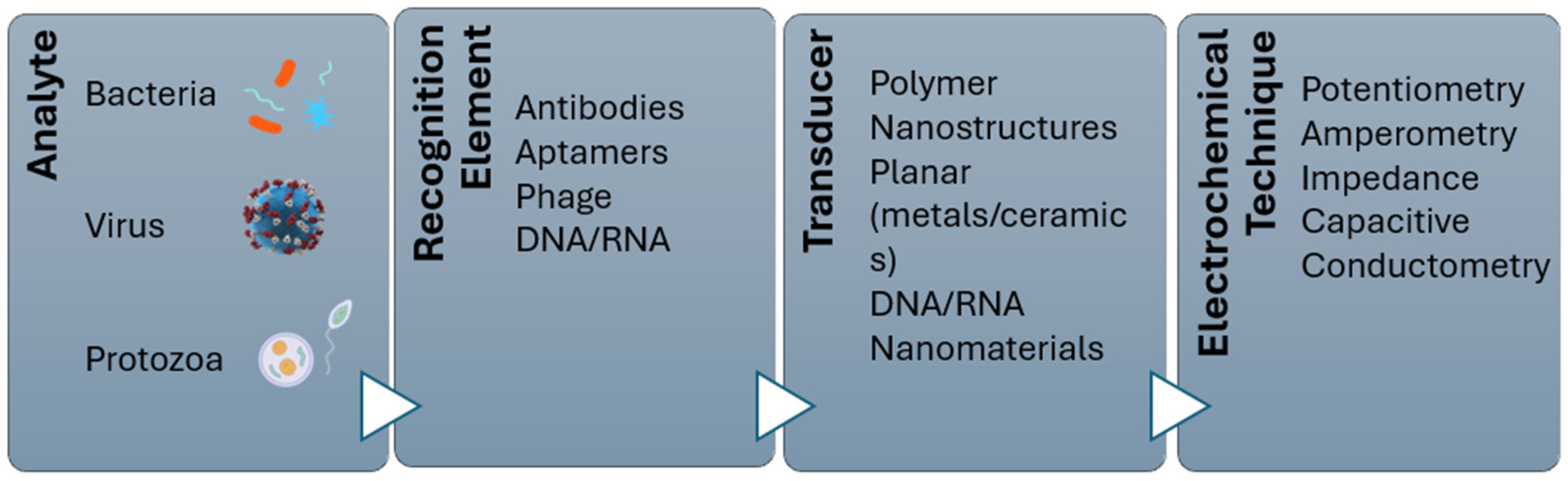

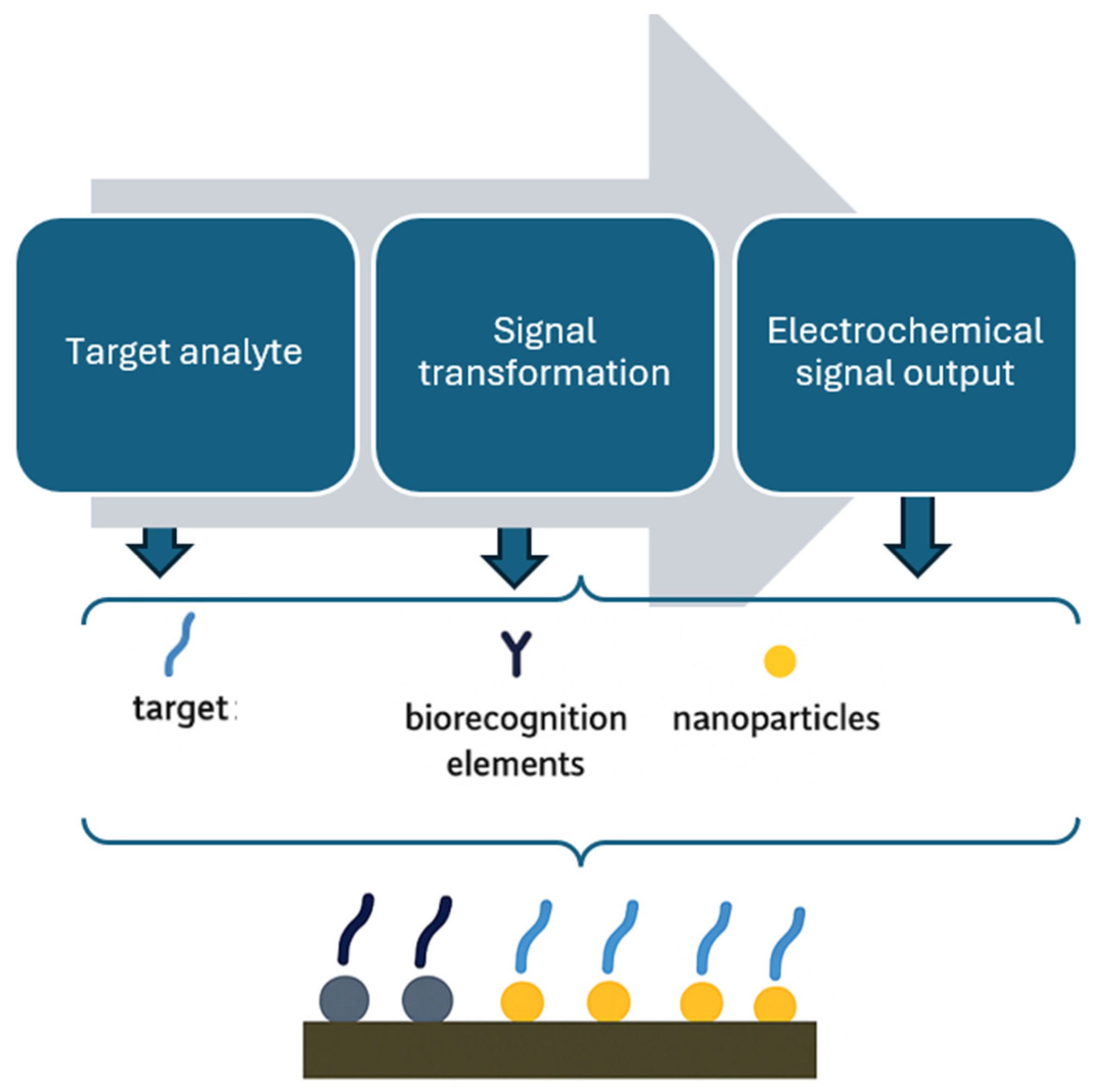

4.1. Electrochemical Biosensor

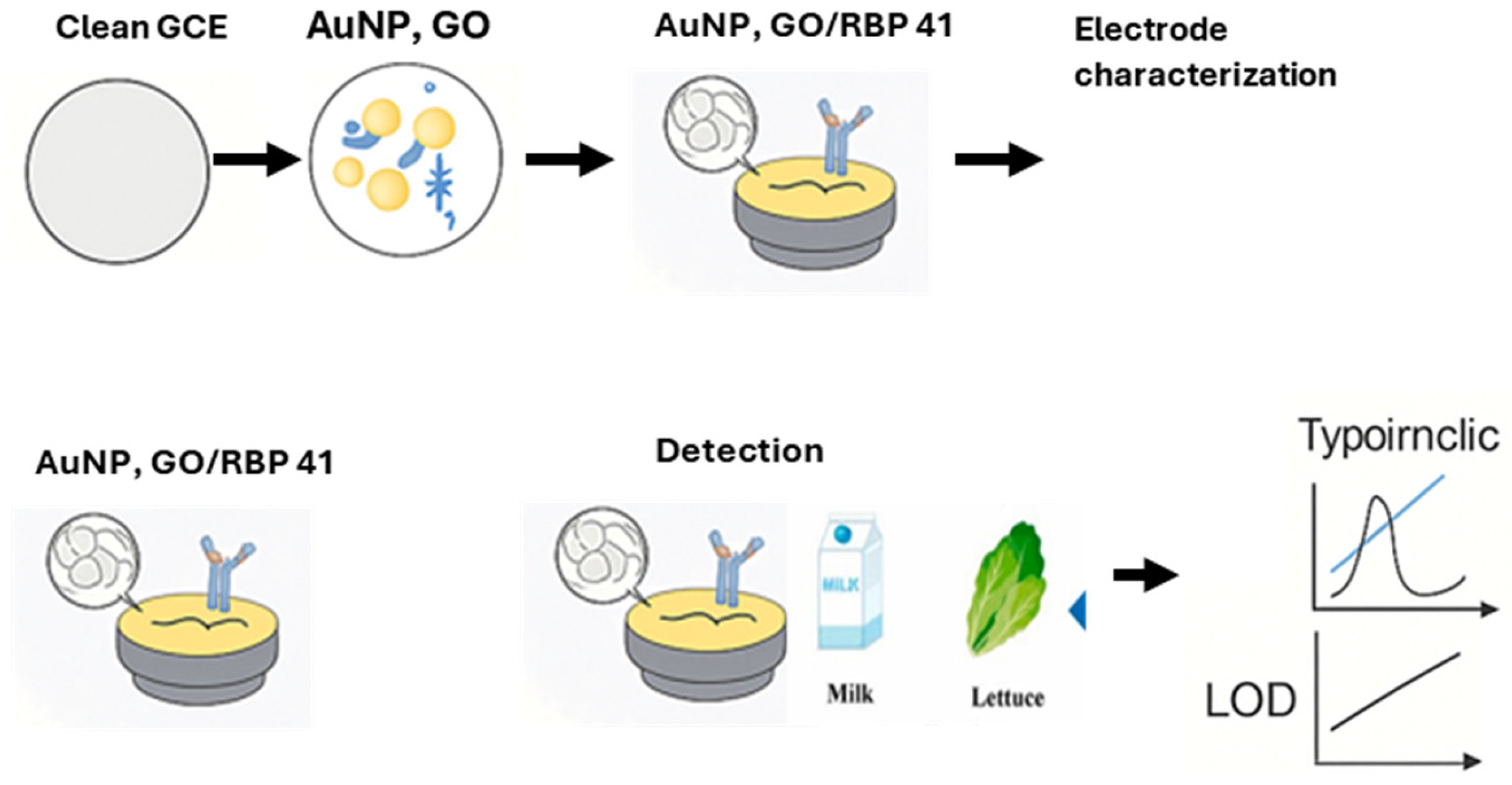

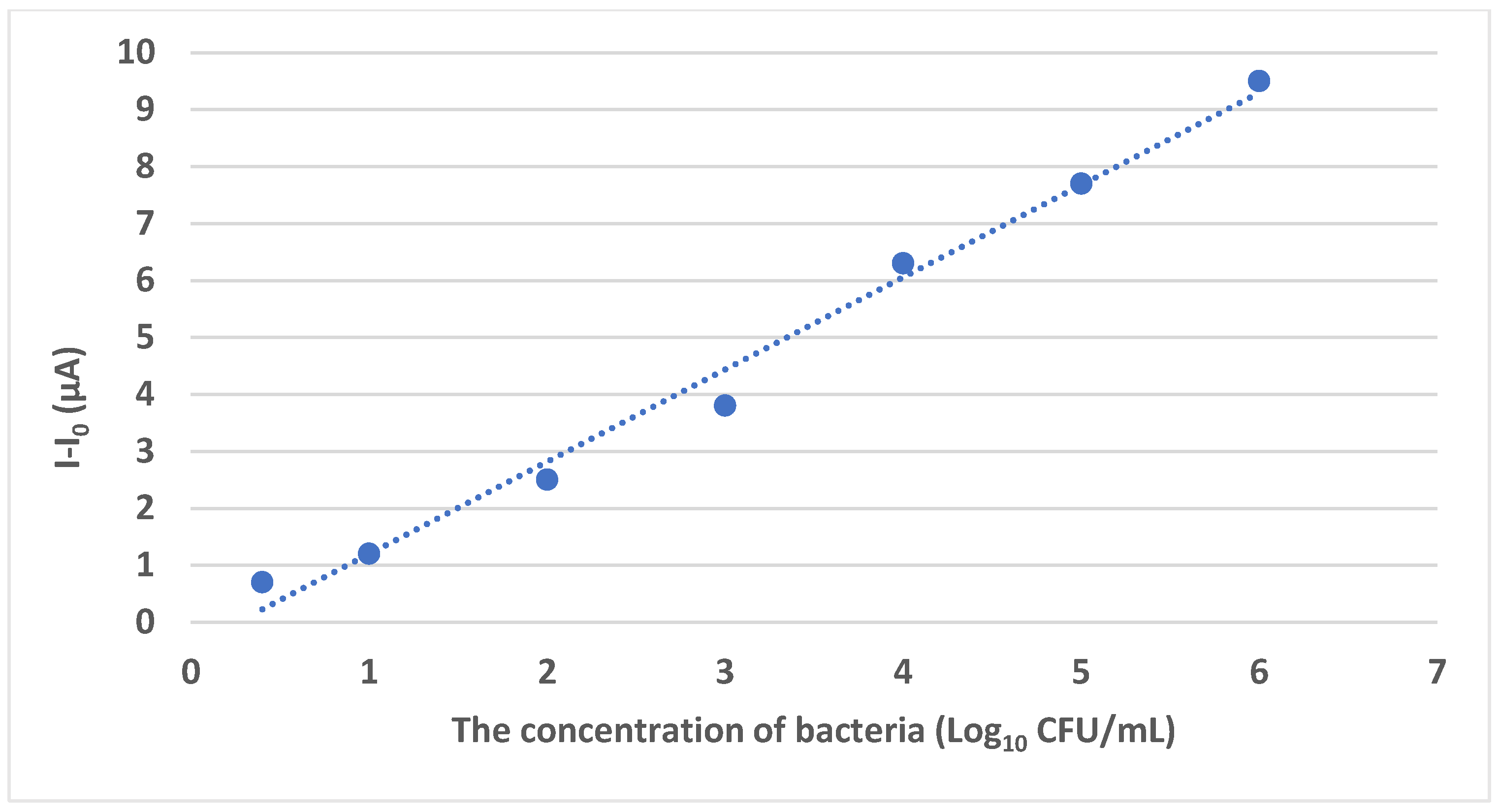

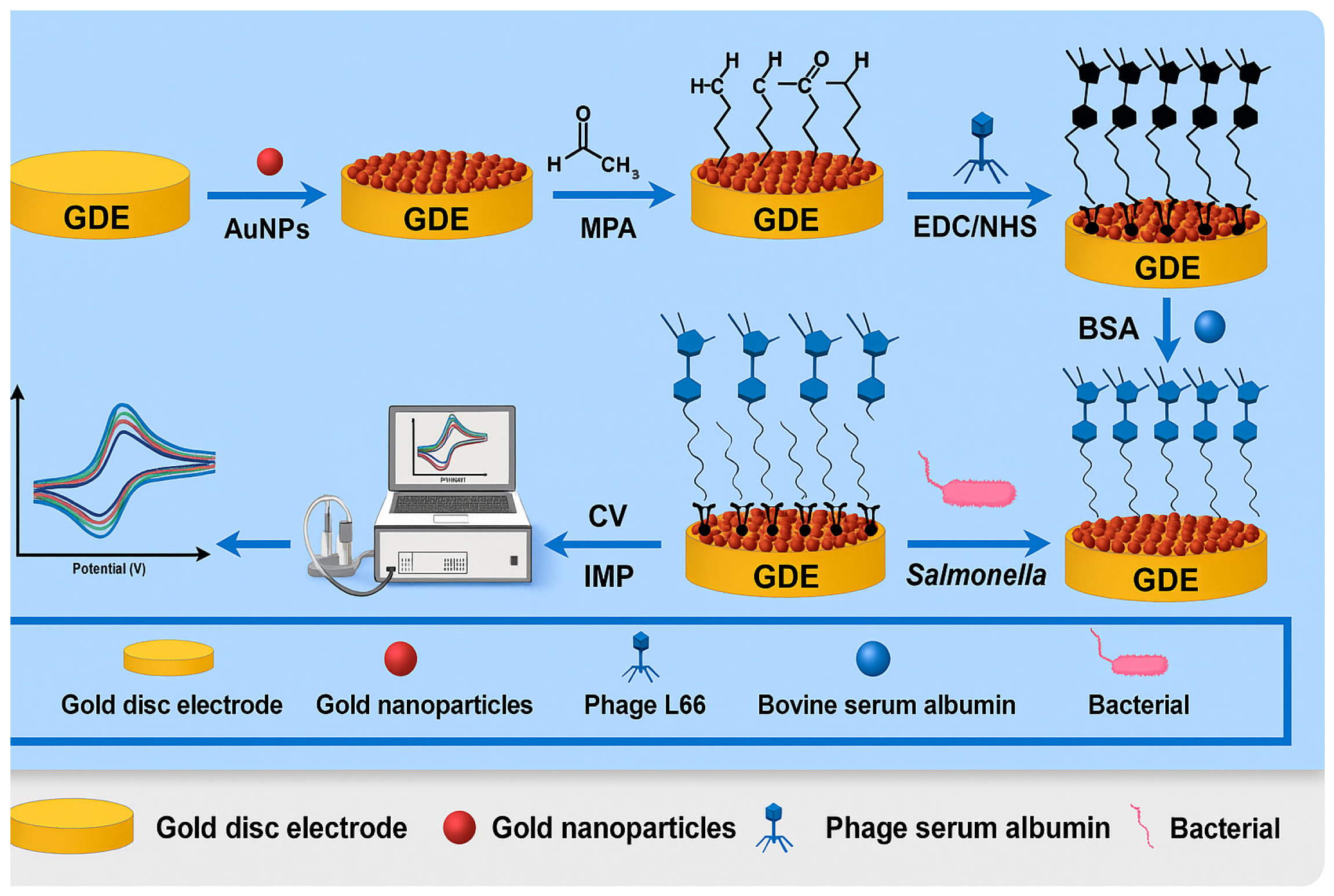

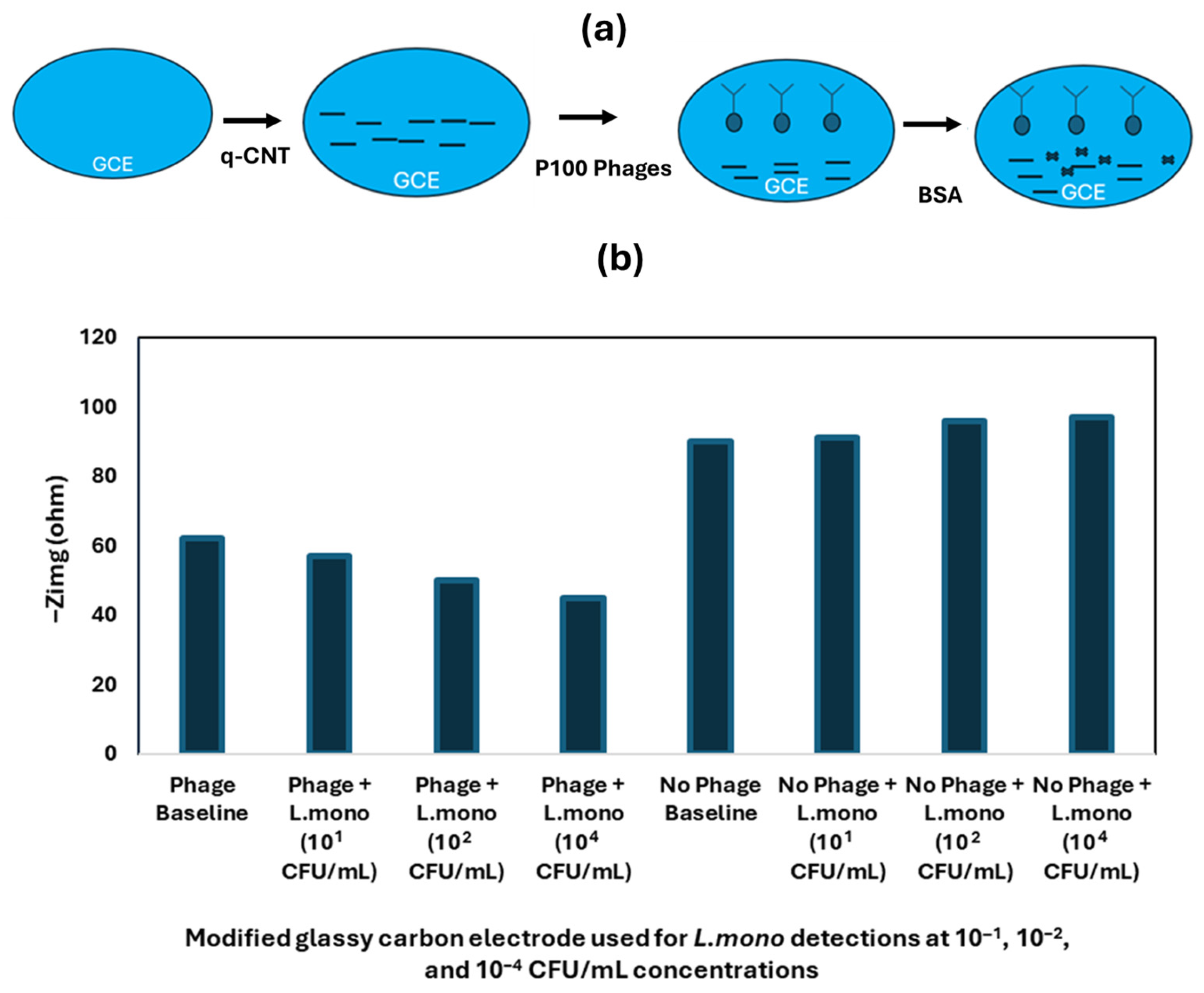

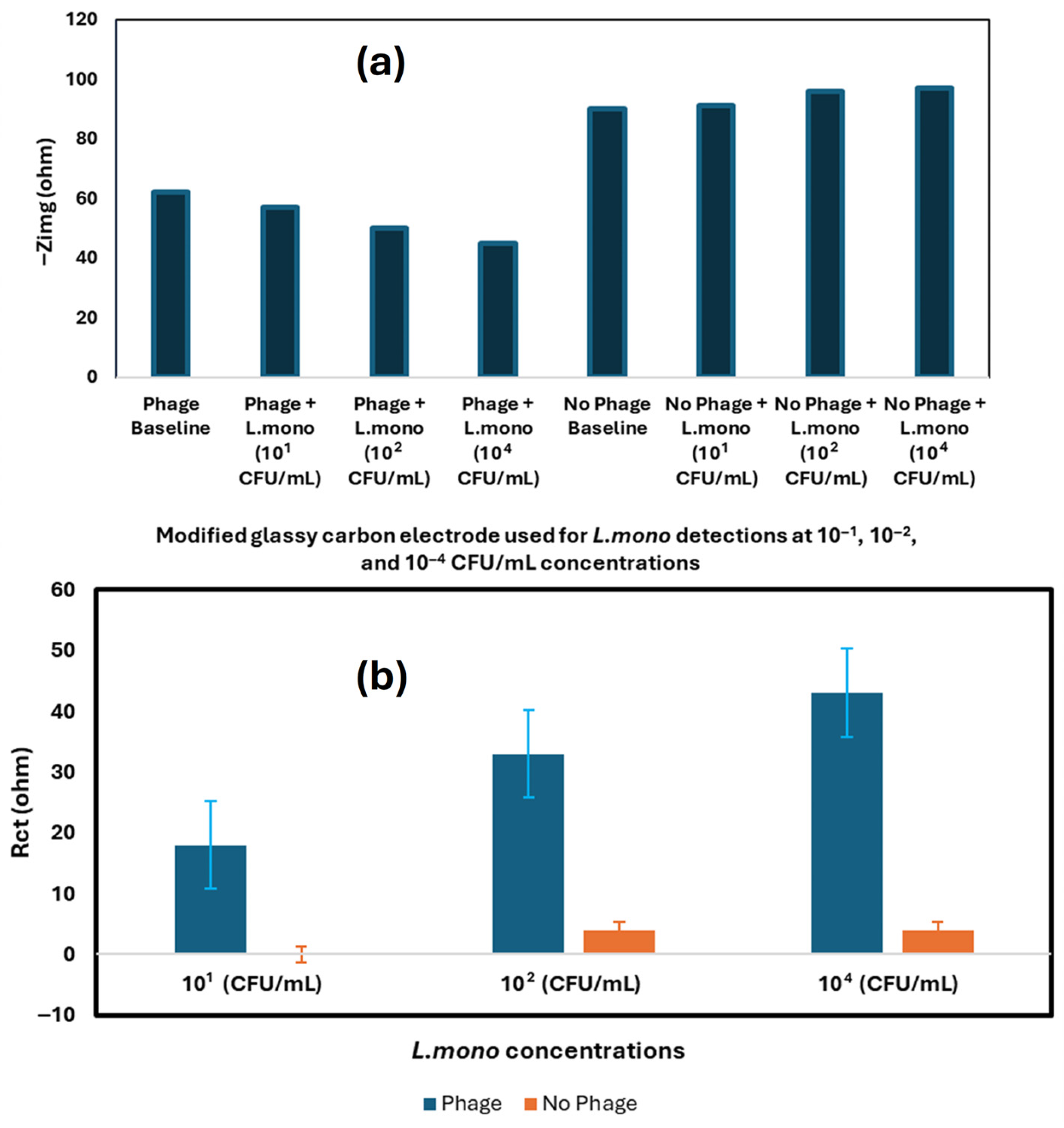

4.1.1. Phage-Based Electrochemical Biosensors

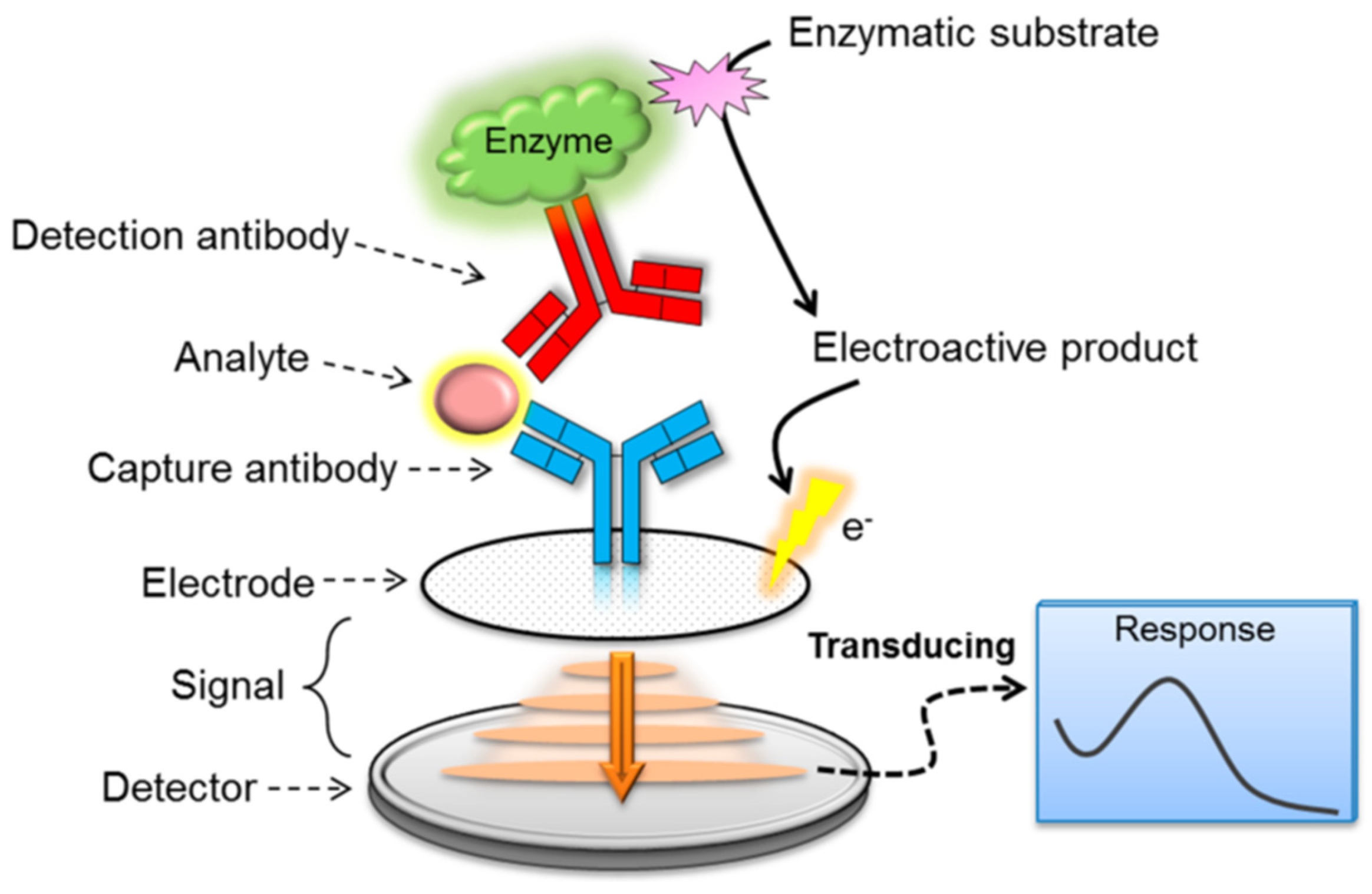

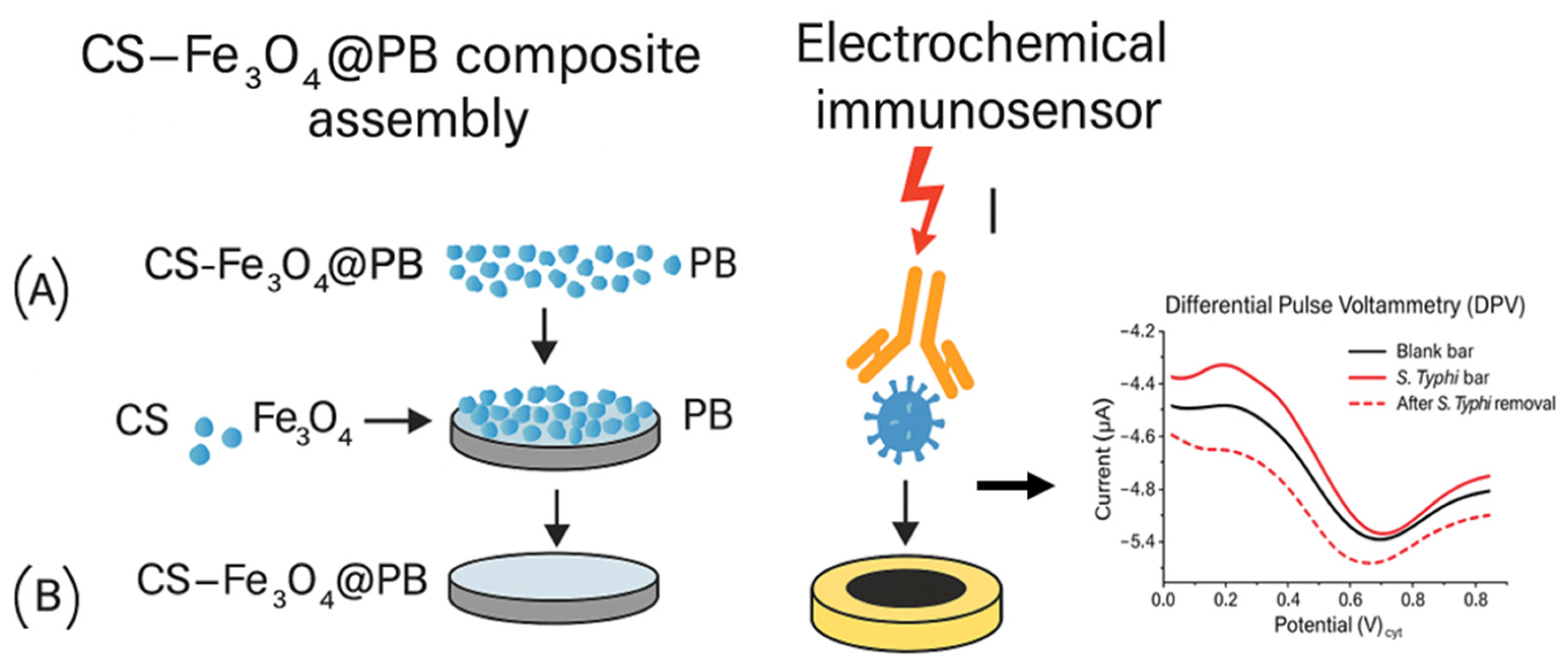

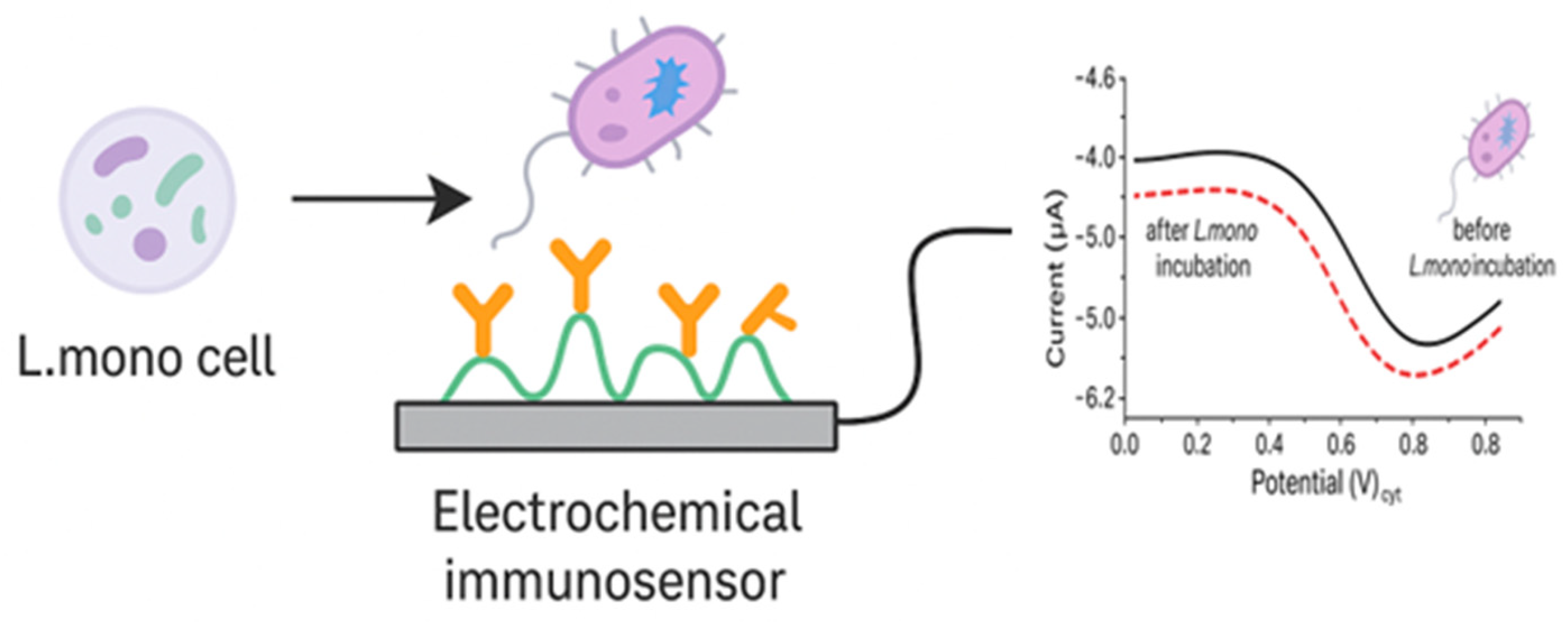

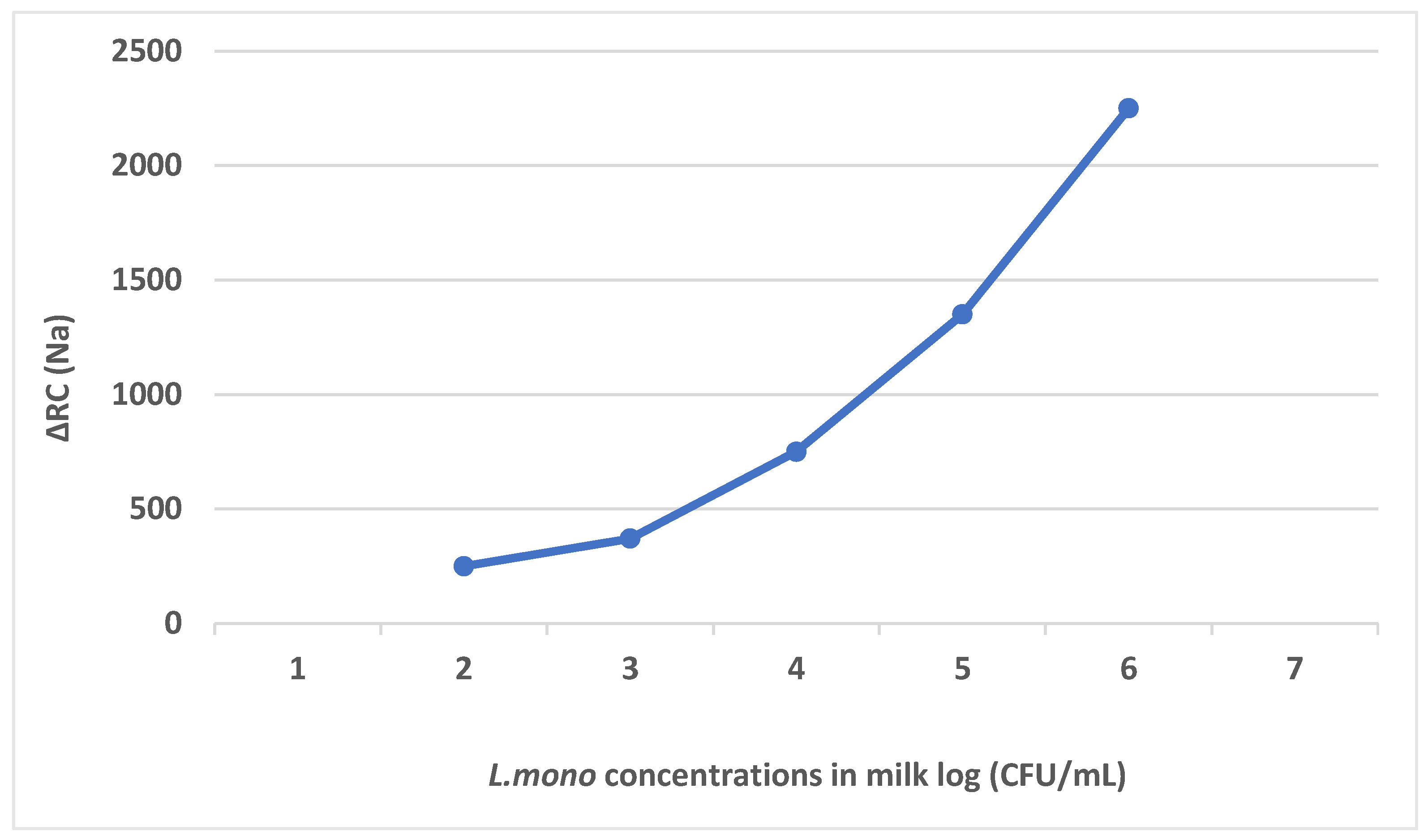

4.1.2. Antibody-Based Electrochemical Biosensors

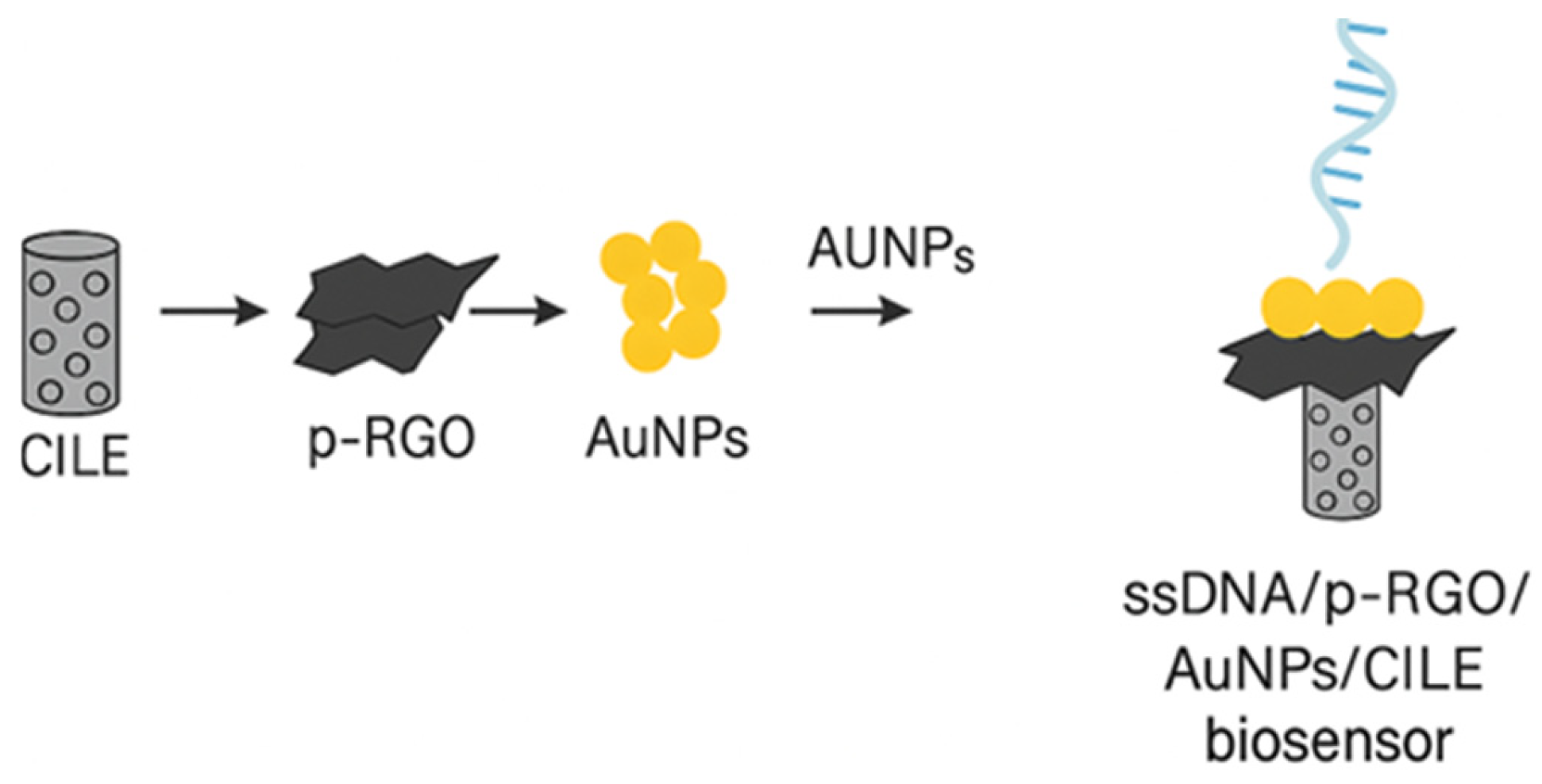

4.1.3. Nucleic Acid-Based Electrochemical Biosensors

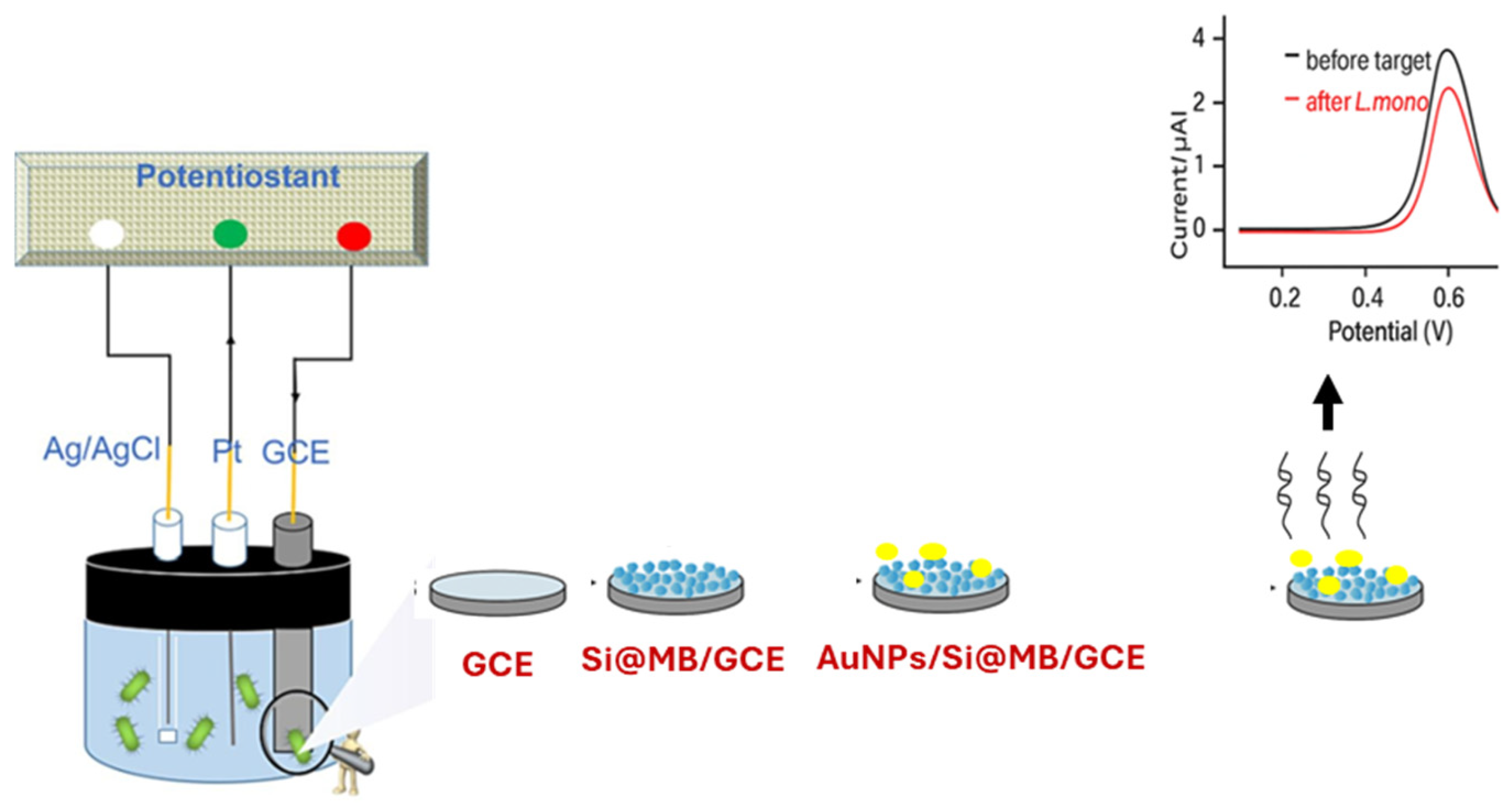

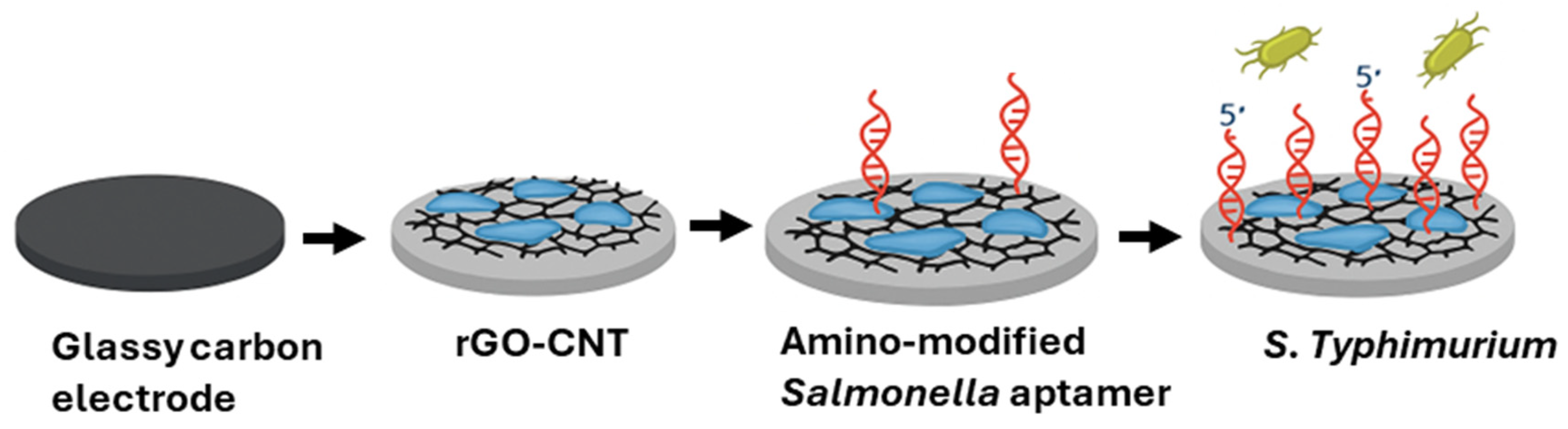

4.1.4. Aptamer-Based Electrochemical Biosensors

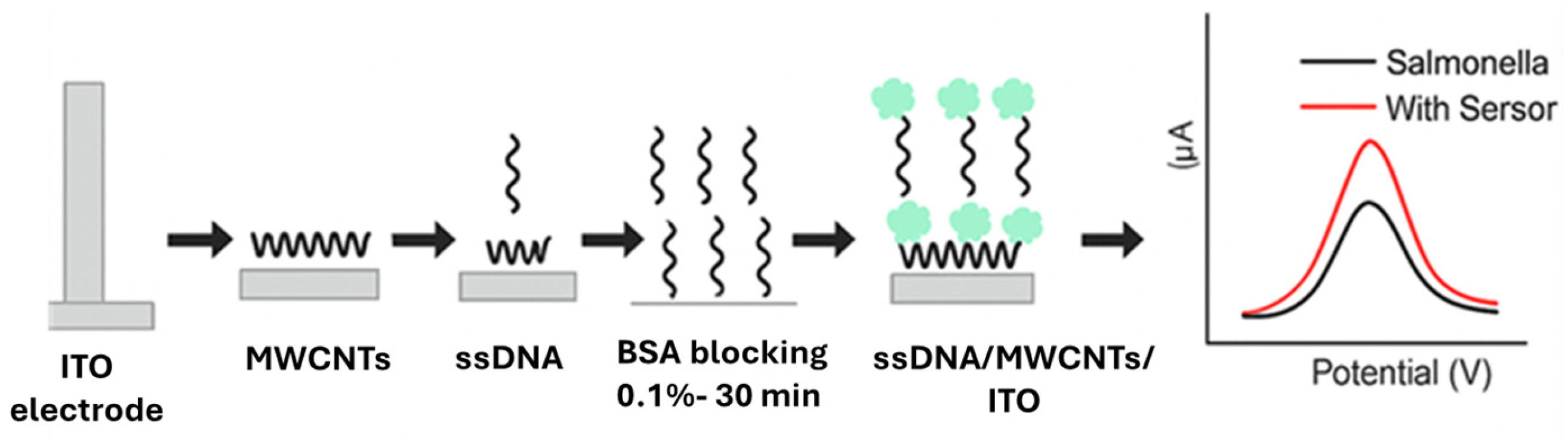

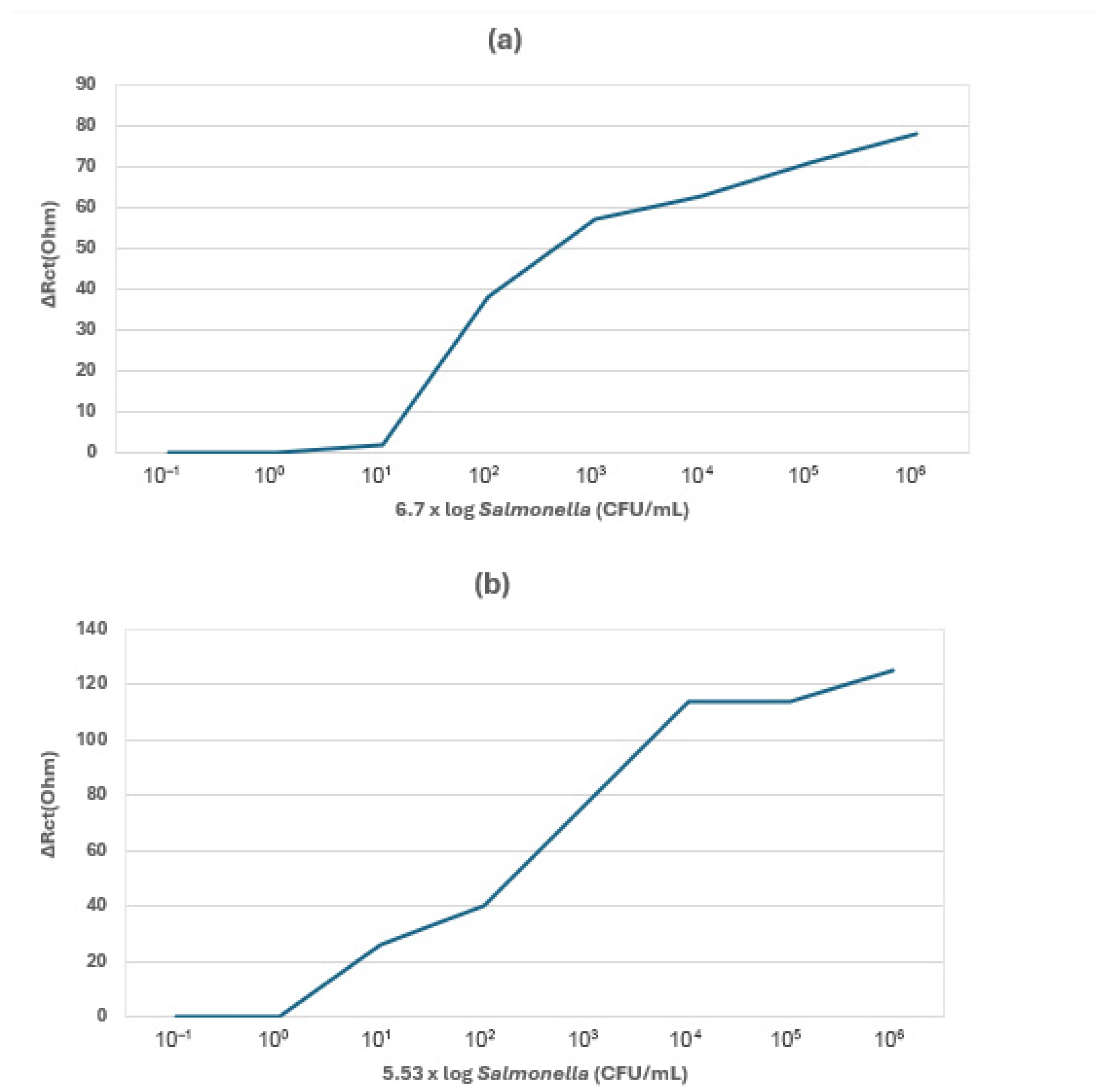

4.1.5. Cell-Based Electrochemical Biosensors

4.1.6. Nanomaterials in Enhancing Electrochemical Biosensor Performance

5. Comparative Performance of Detection Methods

6. Challenges and Future Perspectives of Electrochemical Biosensors

- Environmental stability: Fluctuations in humidity, temperature, and ambient light conditions may affect the sensor’s performance [95].

- Nanomaterials: It is still difficult to achieve perfect carbon nanomaterials and biological elements immobilization to enhance the electrochemical biosensor’s detection performance [96].

- On-site detection: Development of miniaturization electrochemical biosensors for on-site pathogen detection is still a challenge [97].

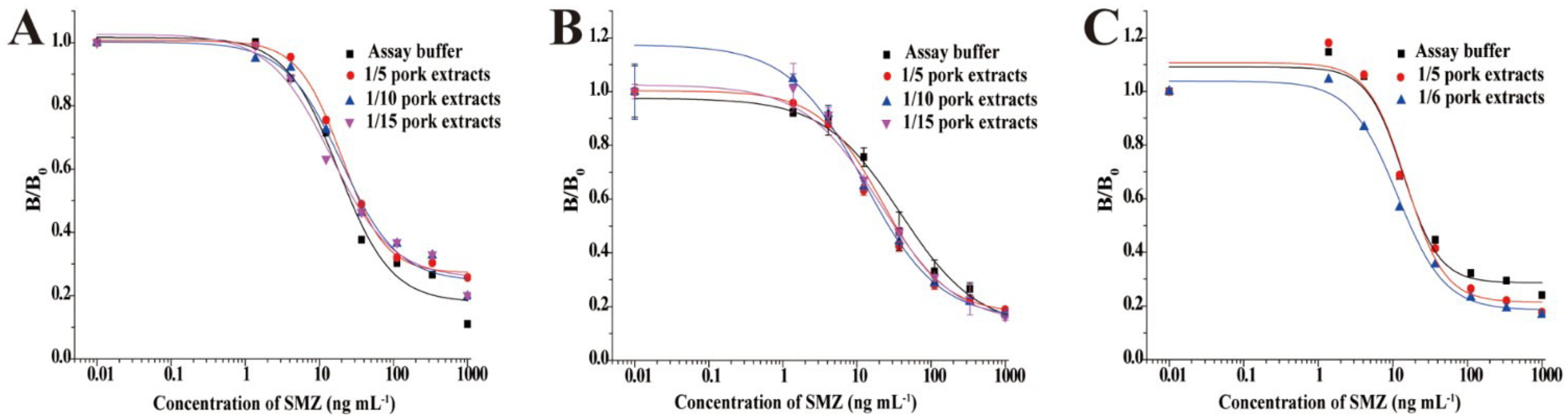

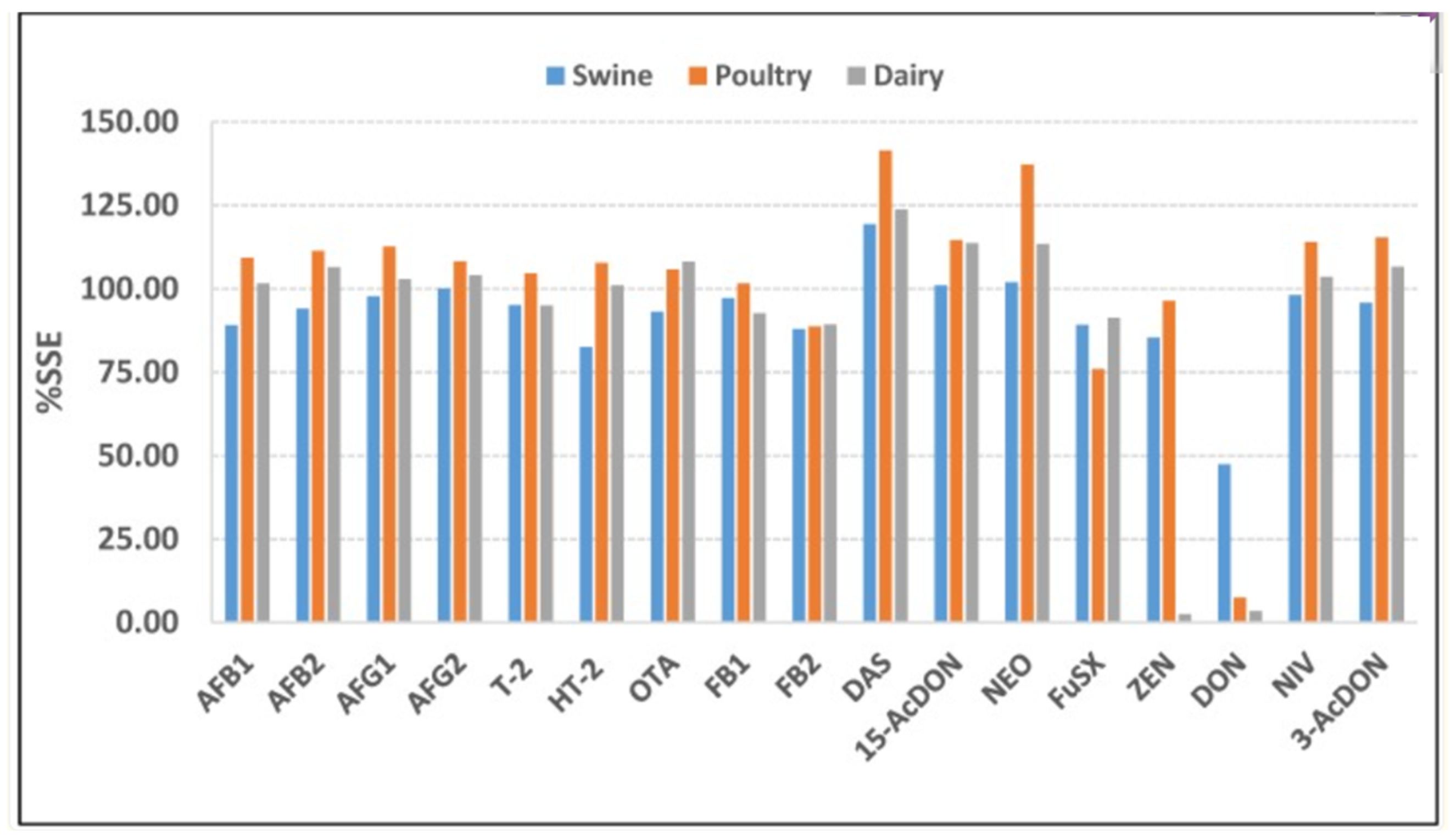

6.1. The Matrix Effect

- (1)

- electrode fouling by proteins/lipid

- (2)

- changes altering electron transfer

6.2. Bacterial Adaptive Response

6.3. Challenges of Sample Preparation and the Need for Lab-on-a-Chip Biosensor

- Sample preparation—Sample preparation is difficult, especially in fruits and vegetables, as they need to be ground and filtered or centrifuged for the removal of large debris such as tissue fragments and plant cells. This process requires multiple centrifuging, pellet resuspension, cell lysis, etc., for improved performance. It is challenging to minimize and integrate these complex procedures into one or two simple steps using only small and basic equipment to allow the operation of the sensor by non-experts with minimal processing time [105].

- Limited microfluidic biosensor sensitivity—This is due to the very small sample volume of less than 100 μL that is often used. The presence of many pathogens is not allowed in many food products, including agrifoods, that is, at least 1 CFU/mL sensitivity is required [109].

- Reagents’ addition—The process of adding reagents to a chip requires human operation, which may increase interference and complexity.

- Less integration of food sample loading and biosensing signal readout with magnetic separation and biosensor—Although Xue et al. [109], have reported in their review great achievements in the integration of magnetic separator and biosensor onto a single chip by many authors, food sample loading and biosensing signal readout still need to be further integrated with a magnetic separator and a biosensor to achieve complete pathogen testing, without potential cross contamination [109].

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elbehiry, A.; Abalkhail, A.; Marzouk, E.; Elmanssury, A.E.; Almuzaini, A.M.; Alfheeaid, H.; Alshahrani, M.T.; Huraysh, N.; Ibrahem, M.; Alzaben, F.; et al. An overview of the public health challenges in diagnosing and controlling human foodborne pathogens. Vaccines 2023, 11, 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castrica, M.; Andoni, E.; Intraina, I.; Curone, G.; Copelotti, E.; Massacci, F.R.; Terio, V.; Colombo, S.; Balzaretti, C.M. Prevalence of Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella spp. in different ready to eat foods from large retailers and canteens over a 2-year period in Northern Italy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gourama, H. Foodborne Pathogens. In Anonymous Food Safety Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 25–49. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-42660-6_2 (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Edel, B.; Glöckner, S.; Stoll, S.; Lindig, N.; Boden, K.; Wassill, L.; Simon, S.; Löffler, B.; Rödel, J. Development of a rapid diagnostic test based on loop-mediated isothermal amplification to identify the most frequent non-typhoidal Salmonella serovars from culture. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2023, 42, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motladiile, T.W.; Tumbo, J.M.; Malumba, A.; Adeoti, B.; Masekwane, N.J.; Mokate, O.M.; Sebekedi, O.C. Salmonella Food-Poisoning Outbreak Linked to the National School Nutrition Programme, North West Province, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 34, a124. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-1df70d6aad (accessed on 16 February 2025). [CrossRef]

- Havelaar, A.H.; Kirk, M.D.; Torgerson, P.R.; Gibb, H.J.; Hald, T.; Lake, R.J.; Praet, N.; Bellinger, D.C.; de Silva, N.R.; Gargouri, N.; et al. World Health Organization global estimates and regional comparisons of the burden of foodborne disease in 2010. PLoS Med. 2015, 12, e1001923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, A.; Kamble, M.P.; Choudhary, P.; Chaturvedi, K.; Kohli, G.; Juneja, V.K.; Sehgal, S.; Taneja, N.K. A surveillance of food borne disease outbreaks in India: 2009–2018. Food Control 2021, 121, 107630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, M.S.; Bustami, Y.; Hamzah, H.H.; Zambry, N.S.; Najib, M.A.; Khalid, M.F.; Aziah, I.; Manaf, A.A. Advancement in Salmonella detection methods: From conventional to electrochemical-based sensing detection. Biosensors 2021, 11, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osek, J.; Lachtara, B.; Wieczorek, K. Listeria monocytogenes in foods-From culture identification to whole-genome characteristics. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 10, 2825–2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chikhi, L.; Mancier, M.; Brugère, H.; Lombard, B.; Faouzi, L.; Guillier, L.; Besse, N.G. Comparison of Listeria monocytogenes alternative detection methods for food microbiology official controls in Europe. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 408, 110448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndraha, N.; Lin, H.-Y.; Tsai, S.-K.; Hsiao, H.-I.; Lin, H.-J. The Rapid Detection of Salmonella enterica, Listeria monocytogenes, and Staphylococcus aureus via polymerase chain reaction combined with magnetic beads and Capillary Electrophoresis. Foods 2023, 12, 3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, E. Detection of Listeria species by conventional culture-dependent and alternative rapid detection methods in retail ready-to-eat foods in Turkey. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 34, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreirinha, C.; Trindade, J.; Saraiva, J.A.; Almeida, A.; Delgadillo, I. MIR spectroscopy as alternative method for further confirmation of foodborne pathogens Salmonella spp. and Listeria monocytogenes. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 3971–3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardo, R.; Duarte, A.; Tavares, L.; Barreto, A.S.; Henriques, A.R. Listeria monocytogenes assessment in a ready-to-eat salad shelf-life study using conventional culture-based methods, genetic profiling, and propidium monoazide quantitative PCR. Foods 2021, 10, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

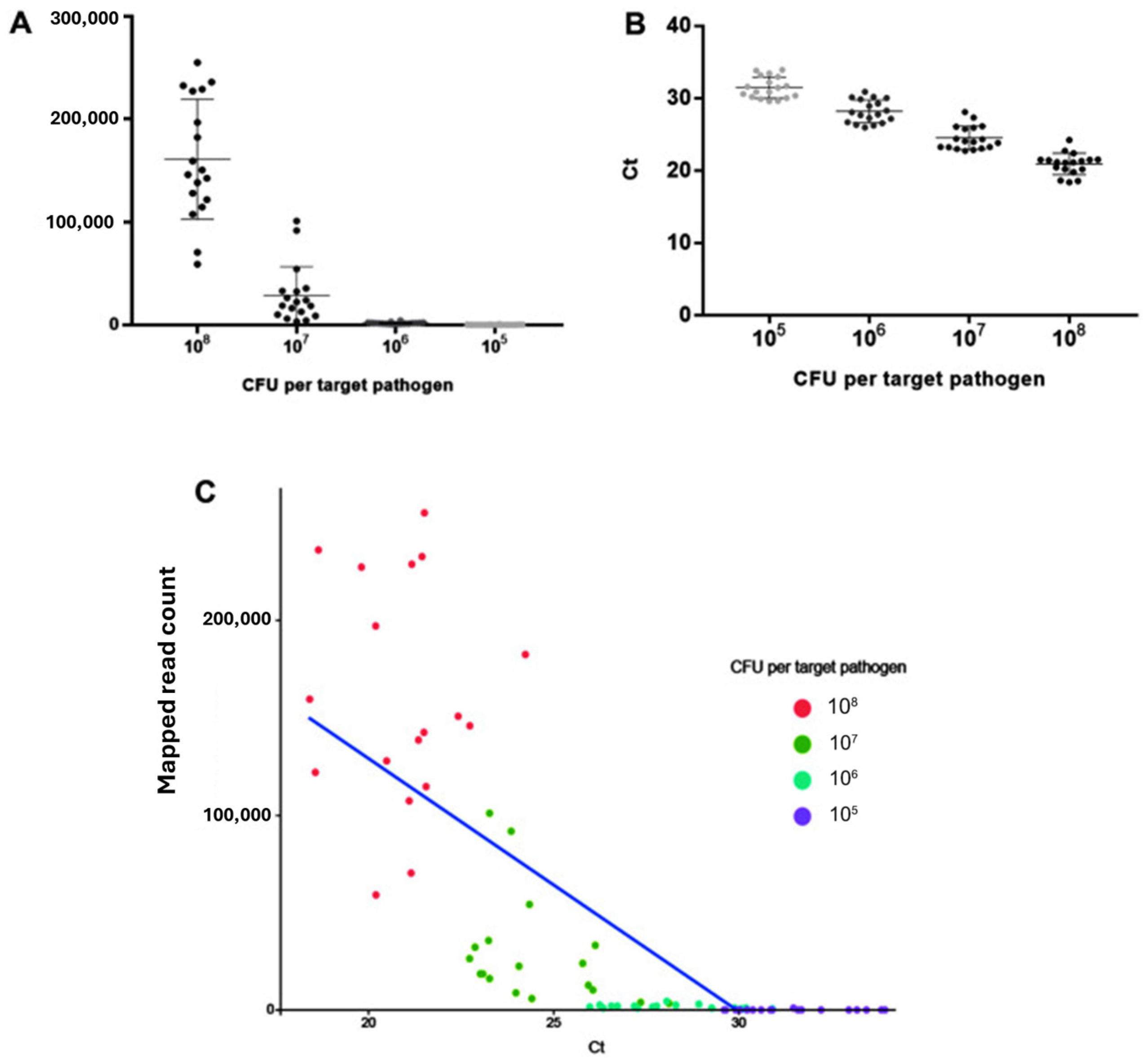

- Bradford, L.M.; Yao, L.; Anastasiadis, C.; Cooper, A.L.; Blais, B.; Deckert, A.; Reid-Smith, R.; Lau, C.; Diarra, M.S.; Carrillo, C.; et al. Limit of detection of Salmonella ser. Enteritidis using culture-based versus culture-independent diagnostic approaches. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0102724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quek, J.J.W.; Wong, J.L.; Tan, J.L.; Yeo, C.C.; Saw, S.H. Integrating Metagenomic and Culture-Based Techniques to Detect Foodborne Pathogens and Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Malaysian Produce. Foods 2025, 14, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kim, S. Bacterial pathogen detection by conventional culture-based and recent alternative (polymerase chain reaction, isothermal amplification, enzyme linked immunosorbent assay, bacteriophage amplification, and gold nanoparticle aggregation) methods in food samples: A review. J. Food Saf. 2020, 41, e12870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foddai, A.C.G.; Grant, I.R. Methods for detection of viable foodborne pathogens: Current state-of-art and future prospects. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 4281–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selim, S.; Harun-Ur-Rashid, M.; Jahan, I.; Mostafa, E.M. Culture-independent molecular techniques for bacterial detection in bivalves. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res. 2024, 50, 585–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurig, S.; Kobialka, R.; Wende, A.; Khan, A.A.; Lübcke, P.; Eger, E.; Schaufler, K.; Daugschies, A.; Truyen, U.; El Wahed, A.A. Rapid reverse purification DNA extraction approaches to identify microbial pathogens in wastewater. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.Y.; Hopping, G.C.; Vaidyanathan, U.; Ronquillo, Y.C.; Hoopes, P.C.; Moshirfar, M. Polymerase Chain Reaction and Its Application in the Diagnosis of Infectious Keratitis. Med. Hypothesis Discov. Innov. Ophthalmol. 2019, 8, 152–155. [Google Scholar]

- Kourti, D.; Angelopoulou, M.; Petrou, P.; Kakabakos, S. Optical immunosensors for bacteria detection in food matrices. Chemosensors 2023, 11, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.A.; McLamore, E.S.; Gomes, C.L. Rapid and label-free Listeria monocytogenes detection based on stimuli-responsive alginate-platinum thiomer nanobrushes. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, D. Recent advances of Raman spectroscopy for the analysis of bacteria. Anal. Sci. Adv. 2023, 4, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Hu, J.; Qu, Z.; Xu, F. Based Immunoassays. In Anonymous Handbook of Immunoassay Technologies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesewski, E.; Johnson, B.N. Electrochemical biosensors for pathogen detection, Biosensors and Bioelectronics. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 159, 112214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naresh, V.; Lee, N. A review on biosensors and recent development of nanostructured materials-enabled biosensors. Sensors 2021, 21, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharff, R.L. Food attribution and economic cost estimates for meat-and poultry-related illnesses. J. Food Prot. 2020, 83, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, S.; White, A.E.; McQueen, R.B.; Ahn, J.-W.; Gunn-Sandell, L.B.; Walter, E.J.S. Economic Burden of Foodborne Illnesses Acquired in the United States. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2025, 22, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladhadh, M. A review of modern methods for the detection of foodborne pathogens. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bintsis, T. Foodborne pathogens. AIMS Microbiol. 2017, 3, 529–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchatchouang, C.-D.K.; Fri, J.; De Santi, M.; Brandi, G.; Schiavano, G.F.; Amagliani, G.; Ateba, C.N. Listeriosis outbreak in South Africa: A comparative analysis with previously reported cases worldwide. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F.; Giaccone, V.; Colavita, G.; Amadoro, C.; Pomilio, F.; Catellani, P. Virulence Characteristics and Distribution of the Pathogen Listeria ivanovii in the Environment and in Food. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vongkamjan, K.; Fuangpaiboon, J.; Turner, M.P.; Vuddhakul, V. Various ready-to-eat products from retail stores linked to occurrence of diverse Listeria monocytogenes and Listeria spp. isolates. J. Food Prot. 2016, 79, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirloni, E.; Centorotola, G.; Pomilio, F.; Torresi, M.; Bernardi, C.; Stella, S. Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat (RTE) delicatessen foods: Prevalence, genomic characterization of isolates and growth potential. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 410, 110515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahab, A.; Chaudhary, S.; Ahmad, A.; Kollu, V.; Smith, S. A life-devastating cause of gastroenteritis in an immunocompetent host: Was it suspected? Clin. Case Rep. 2017, 6, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanaway, J.D.; Parisi, A.; Sarkar, K.; Blacker, B.F.; Reiner, R.C.; Hay, S.I.; Nixon, M.R.; Dolecek, C.; James, S.L.; Mokdad, A.H. The global burden of non-typhoidal Salmonella invasive disease: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 1312–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashazadeh, P.; Mokhtarzadeh, A.; Hasanzadeh, M.; Hejazi, M.; Hashemi, M.; de la Guardia, M. Nanomaterials for use in sensing of Salmonella infections: Recent advances. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 87, 1050–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Li, H.; Zhang, T.; Chu, Y.; Zuo, J.; Chen, D. Study on antibiotic susceptibility of Salmonella Typhimurium L forms to the third and fourth generation cephalosporins. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanka, B.; Patil, R.K.; Dwarakanath, S. A review on detection methods used for foodborne pathogens. Indian J. Med. Res. 2016, 144, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLain, J.E.; Cytryn, E.; Durso, L.M.; Young, S. Culture-based methods for detection of antibiotic resistance in agroecosystems: Advantages, challenges, and gaps in knowledge. J. Environ. Qual. 2016, 45, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, A.; Treglia, I.; Ciccaglioni, G.; Ortoffi, M.F.; Gattuso, A. Application of a Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) assay for the detection of listeria monocytogenes in cooked ham. Foods 2023, 12, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, C.; Zubair, M.; Gupta, V. Molecular genetics testing. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: St. Petersburg, FL, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560712/ (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Brown, Z.J.; Patwardhan, S.; Bean, J.; Pawlik, T.M. Molecular diagnostics and biomarkers in cholangiocarcinoma. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 44, 101851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikhaylin, S.; Bazinet, L. Fouling on ion-exchange membranes: Classification, characterization and strategies of prevention and control. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 229, 34–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.; Xu, L.; Li, Y. Biosensors for rapid detection of Salmonella in food: A review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 20, 149–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIlwaine, D.B.; Moore, M.; Corrigan, A.; Niemaseck, B.; Nicoletti, D. A Comparison of the Microbial Populations in a Culture-Dependent and a Culture-Independent Analysis of Industrial Water Samples. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 4, 1079–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altheide, S.T. Biochemical and culture-based approaches to identification in the diagnostic microbiology laboratory. Am. Soc. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2019, 32, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6887-2:2003; Microbiology of Food and Animal Feeding Stuffs—Preparation of Test Samples, Initial Suspension and Decimal Dilution for Microbiological Examination. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- ISO 11290-1; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Detection and Enumeration of Listeria monocytogenes and of Listeria spp. Part 1: Detection Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ISO 11290-2:2017; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Detection and Enumeration of Listeria monocytogenes and of Listeria spp. Part 2: Enumeration Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Li, P.; Feng, X.; Chen, B.; Wang, X.; Liang, Z.; Wang, L. The detection of foodborne pathogenic bacteria in seafood using a multiplex polymerase chain reaction system. Foods 2022, 11, 3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, T.; Dong, Q.; Li, J.; Niu, C. Detection of 12 common food-borne bacterial pathogens by TaqMan real-time PCR using a single set of reaction conditions. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.-G.; Ha, E.-S.; Kang, B.; Choi, I.; Kwak, J.-E.; Choi, J.; Park, J.; Lee, W.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, S.H.; et al. Development and evaluation of a next-generation sequencing panel for the multiple detection and identification of pathogens in fermented foods. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 33, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khehra, N.; Padda, I.S.; Swift, C.J. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). 2023. Available online: https://europepmc.org/article/NBK/nbk589663 (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Mandal, P.K.; Biswas, A.K. Modern techniques for rapid detection of meatborne pathogens. In Anonymous Meat Quality Analysis; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satam, H.; Joshi, K.; Mangrolia, U.; Waghoo, S.; Zaidi, G.; Rawool, S.; Thakare, R.P.; Banday, S.; Mishra, A.K.; Das, G.; et al. Next-generation sequencing technology: Current trends and advancements. Biology 2023, 12, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheamfour, C.L.; Parveen, S.; Gutierrez, A.; Handy, E.T.; Behal, S.; Kim, D.; Kim, S.; East, C.; Xiong, R.; Haymaker, J.R.; et al. Detection of Salmonella enterica and Listeria monocytogenes in Alternative Irrigation Water by Culture and qPCR-Based Methods in the Mid-Atlantic US. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0353623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Domesle, K.J.; Ge, B. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification for Salmonella detection in food and feed: Current applications and future directions. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2018, 15, 309–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozel, K.; Healy, S.; Hassan, M.M. Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP): A Simple Method for the Detection of Foodborne Pathogens. In Anonymous Foodborne Pathogens; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J.W.-F.; Ab Mutalib, N.-S.; Chan, K.-G.; Lee, L.-H. Rapid methods for the detection of foodborne bacterial pathogens: Principles, applications, advantages and limitations, Frontiers in microbiology. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 5, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Maestu, A.; Azinheiro, S.; Carvalho, J.; Prado, M. Combination of immunomagnetic separation and real-time recombinase polymerase amplification (IMS-qRPA) for specific detection of Listeria monocytogenes in smoked salmon samples. J. Food Sci. 2019, 84, 1881–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, P.; Wang, L.; He, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Fu, S.; Qin, X.; Chen, Q.; Man, C.; Jiang, Y. An enhanced lateral flow assay based on aptamer–magnetic separation and multifold AuNPs for ultrasensitive detection of Salmonella Typhimurium in milk. Foods 2021, 10, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penner, M.H. Basic principles of spectroscopy. In Food Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Lorenzo, L.; Garrido-Maestu, A.; Bhunia, A.K.; Espiña, B.; Prado, M.; Diéguez, L.; Abalde-Cela, S. Gold nanostars for the detection of foodborne pathogens via surface-enhanced Raman scattering combined with microfluidics. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2019, 2, 6081–6086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6579-1; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Detection, Enumeration and Serotyping of Salmonella. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Pereira, J.M.; Leme, L.M.; Perdoncini, M.R.F.G.; Valderrama, P.; Março, P.H. Fast discrimination of milk contaminated with Salmonella sp. via near-infrared spectroscopy. Food Anal. Methods 2017, 11, 1878–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Techakasikornpanich, M.; Jangpatarapongsa, K.; Polpanich, D.; Zine, N.; Errachid, A.; Elaissari, A. Biosensor technologies: DNA-based approaches for foodborne pathogen detection. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 180, 117925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saasa, V.; Orasugh, J.T.; Mwakikunga, B.; Ray, S.S. Electrospun rGO-PVDF/WO3 composite fibers for SO2 sensing. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2024, 181, 108631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feleni, U.; Morare, R.; Masunga, G.S.; Magwaza, N.; Saasa, V.; Madito, M.J.; Managa, M. Recent developments in waterborne pathogen detection technologies. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, C.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Wang, X. An electrochemical biosensor based on phage-encoded protein RBP 41 for rapid and sensitive detection of Salmonella. Talanta 2023, 270, 125561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saasa, V.; Chibagidi, R.; Ipileng, K.; Feleni, U. Advances in cancerdetection: A review on electrochemical biosensor technologies. Sens. Bio-Sensing Res. 2025, 49, 100826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, M.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Ding, L.; Xiong, C.; Huang, G.; Zhang, J. Label-free electrochemical immunosensor based on an internal and external dual-signal synergistic strategy for the sensitive detection of Salmonella in food. Food Biosci. 2024, 61, 105006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Peng, Y.; Bai, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Fan, X.; Ning, B.; Gao, Z. Rapid detection of Listeria monocytogenes in milk by self-assembled electrochemical immunosensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 190, 900–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saucedo, N.M.; Srinives, S.; Mulchandani, A. Electrochemical biosensor for rapid detection of viable bacteria and antibiotic screening. J. Anal. Test. 2019, 3, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majer-Baranyi, K.; Székács, A.; Adányi, N. Application of electrochemical biosensors for determination of food spoilage. Biosensors 2023, 13, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolti, O.; Suganthan, B.; Maynard, R.; Asadi, H.; Locklin, J.; Ramasamy, R.P. Electrochemical biosensor for rapid detection of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2022, 169, 067510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Yang, Q.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, W.; Zhang, W. An ultrasensitive and specific ratiometric electrochemical biosensor based on SRCA-CRISPR/Cas12a system for detection of Salmonella in food. Food Control 2022, 146, 109528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinshaw, I.J.; Muniandy, S.; Teh, S.J.; Ibrahim, F.; Leo, B.F.; Thong, K.L. Development of an aptasensor using reduced graphene oxide chitosan complex to detect Salmonella. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2017, 806, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, R.; Pulingam, T.; Appaturi, J.N.; Zifruddin, A.N.; Teh, S.J.; Lim, T.W.; Ibrahim, F.; Leo, B.F.; Thong, K.L. Thong, Carbon nanotube-based aptasensor for sensitive electrochemical detection of whole-cell Salmonella. Anal. Biochem. 2018, 554, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appaturi, J.N.; Pulingam, T.; Thong, K.L.; Muniandy, S.; Ahmad, N.; Leo, B.F. Rapid and sensitive detection of Salmonella with reduced graphene oxide-carbon nanotube based electrochemical aptasensor. Anal. Biochem. 2020, 589, 113489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolti, O.; Suganthan, B.; Nagdeve, S.N.; Maynard, R.; Locklin, J.; Ramasamy, R.P. Investigation of the Efficacy of a Listeria monocytogenes Biosensor Using Chicken Broth Samples. Sensors 2024, 24, 2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. Properties of a novel Salmonella phage L66 and its application based on electrochemical sensor-combined AuNPs to detect Salmonella. Foods 2022, 11, 2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-H.; Bong, J.-H.; Jung, J.; Sung, J.S.; Lee, G.-Y.; Kang, M.-J.; Pyun, J.-C. Microbial biosensor for Salmonella using anti-bacterial antibodies isolated from human serum. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2021, 144, 109721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prajapati, V.; Shrivastav, P. Bioreceptors for Antigen–Antibody Interactions. In Biosensors Nanotechnology; Scrivener Publishing LLC: Beverly, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, I.; Lee, J.; Kim, J.; Kang, M.; Paik, J.K.; Ku, S.; Cho, H.; Irudayaraj, J.; Kim, D. Current technologies of electrochemical immunosensors: Perspective on signal amplification. Sensors 2018, 18, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, H.; Neelam, R. Enzyme-based electrochemical biosensors for food safety: A review. Nanobiosensors Dis. Diagn. 2016, 5, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Zheng, W.; Yin, C.; Weng, W.; Li, G.; Sun, W.; Men, Y. Electrochemical DNA biosensor based on gold nanoparticles and partially reduced graphene oxide modified electrode for the detection of Listeria monocytogenes hly gene sequence. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2017, 806, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, F.; Esnaashari, S.S.; Webster, T.J.; Khosravani, M.; Adabi, M. Polymeric nanoparticles for drug delivery in glioblastoma: State of the art and future perspectives. J. Control. Release 2022, 349, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S.G.; Shi, X. Highly sensitive detection of L. monocytogenes using an electrochemical biosensor based on Si@ MB/AuNPs modified glassy carbon electrode. Microchem. J. 2023, 194, 109357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Manik, S. Detection of Listeria monocytogenes using Biosensor in Food system. Food Control 2025, 178, 111485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zang, L. Electrochemical cell-based sensor for detection of food hazards. Micromachines 2021, 12, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Belwal, T.; Li, L.; Lin, X.; Xu, Y.; Luo, Z. Nanomaterial-based biosensors for sensing key foodborne pathogens: Advances from recent decades. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 1465–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azinheiro, S.; Carvalho, J.; Prado, M.; Garrido-Maestu, A. Multiplex detection of Salmonella spp., E. coli O157 and L. monocytogenes by qPCR melt curve analysis in spiked infant formula. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, E.N.S.E.A.; Irekeola, A.A.; Yusof, N.Y.; Yean, C.Y. Enhancing food safety: A systematic review of electrochemical biosensors for pathogen detection–advancements, limitations, and practical challenges. Food Control 2025, 179, 111603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curulli, A. Electrochemical biosensors in food safety: Challenges and perspectives. Molecules 2021, 26, 2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; He, C.; Zeng, W.; Luo, Y.; Liu, C.; Yang, M.; Kuang, Y.; Lin, X.; Huang, Q. Electrochemical biosensors for foodborne pathogens detection based on carbon nanomaterials: Recent advances and challenges. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2022, 15, 498–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, S.; Levent, S.; Can, N.Ö. Solvent-Based and Matrix-Matched Calibration Methods on Analysis of Ceftiofur Residues in Milk and Pharmaceutical Samples Using a Novel HPLC Method. Vet. Med. Sci. 2024, 10, e70080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, J.F. Consideration of sample matrix effects and “biological” noise in optimizing the limit of detection of biosensors. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 3290–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.L.; Olomukoro, A.A.; Emmons, R.V.; Godage, N.H.; Gionfriddo, E. Matrix effects demystified: Strategies for resolving challenges in analytical separations of complex samples. J. Sep. Sci. 2023, 46, e2300571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Song, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Q. Evaluation of different food matrices via a dihydropteroate synthase-based biosensor for the screening of sulfonamide residues. Food Agric. Immunol. 2020, 31, 352–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nualkaw, K.; Poapolathep, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Giorgi, M.; Li, P.; Logrieco, A.F.; Poapolathep, A. Simultaneous Determination of Multiple Mycotoxins in Swine, Poultry and Dairy Feeds Using Ultra High Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Toxins 2020, 12, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Ordonez, A.; Broussolle, V.; Colin, P.; Nguyen-The, C.; Prieto, M. The adaptive response of bacterial food-borne pathogens in the environment, host and food: Implications for food safety. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 213, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Yang, W.; Zhu, W.; Yu, D. Innovative applications and research advances of bacterial biosensors in medicine. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1507491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, Y.Y.; Kim, B. Lab-on-a-chip pathogen sensors for food safety. Sensors 2012, 12, 10713–10741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nnachi, R.C.; Sui, N.; Ke, B.; Luo, Z.; Bhalla, N.; He, D.; Yang, Z. Biosensors for rapid detection of bacterial pathogens in water, food and environment. Environ. Int. 2022, 166, 107357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.M. Challenges in lab-on-a-chip technology. Front. Lab Chip Technol. 2022, 1, 979398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonchamps, P.L.; He, Y.; Wang, K.; Lu, X. Detection of pathogens in foods using microfluidic “lab-on-chip”: A mini review. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 10, 100430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Jiang, F.; Xi, X.; Li, Y.; Lin, J. Lab-on-chip separation and biosensing of pathogens in agri-food. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 137, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolti, O.; Suganthan, B.; Ramasamy, R.P. Lab-on-a-chip electrochemical biosensors for foodborne pathogen detection: A review of common standards and recent progress. Biosensors 2023, 13, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Srivatsa, P.; Ahmadzai, F.H.; Liu, Y.; Song, X.; Karpatne, A.; Kong, Z.; Johnson, B.N. Reduction of biosensor false responses and time delay using dynamic response and theory-guided machine learning. ACS Sens. 2023, 8, 4079–4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wan, J.; Wang, X.; Zhou, X.; Li, X.; Zhou, W. Research Progress on Multiplexed Pathogen Detection Using Optical Biosensors. Biosensors 2025, 15, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaci, K.; Enebral-Romero, E.; Martínez-Periñán, E.; Garrido, M.; Pérez, E.M.; López-Diego, D.; Luna, M.; González-De-Rivera, G.; García-Mendiola, T.; Lorenzo, E. Multiplex portable biosensor for bacteria detection. Biosensors 2023, 13, 958. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2079-6374/13/11/958# (accessed on 15 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.P.; Wucher, B.R.; Nadell, C.D.; Foster, K.R. Bacterial defences: Mechanisms, evolution and antimicrobial resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalambate, P.K.; Rao, Z.; Dhanjai; Wu, J.; Shen, Y.; Boddula, R.; Huang, Y. Electrochemical (bio) sensors go green. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 163, 112270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Guo, W.; Li, C.; Xu, H.; Zhang, X.; Zou, X.; Sun, Z. Fe3O4@ Au Nanoparticle-Enabled Magnetic Separation Coupled with CRISPR/Cas12a for Ultrasensitive Detection of Foodborne Pathogens. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 13949–13959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Techniques | Examples of the Techniques | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Culture-based methods | Agar plate, antibiotic susceptibility testing, blood cultures, enrichment, biochemical tests, etc. | [10] |

| Molecular-based assays | Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), polymerase chain reaction (PCR), whole genome sequencing, nucleic acid sequence-based amplification (NASBA), DNA microarrays, and recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA). | [11] |

| Immunological-based assays | Immunochromatography assay, latex agglutination method, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and enzyme-linked fluorescent assay (ELFA). | [12] |

| Spectroscopy-based methods | Optical phenotyping with light diffraction technology, Raman spectroscopy, hyperspectral imaging (HIS), and near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy. | [13] |

| Mass spectrometry-based methods | Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI–TOF MS). | [8] |

| Salad Code | Incubation Temperature | Number of L. mono Presumptive Colonies Obtained at Day 0, Day 4, and Day 8 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 0 | Day 4 | Day 8 | ||

| 1 | 4 °C | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 4 °C | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 3 | 4 °C | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| 4 | 12 °C | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 5 | 12 °C | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 6 | 12 °C | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 16 °C | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| 8 | 16 °C | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 9 | 16 °C | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Species Detected | Food Sample | Limit of Detection | Detection Method | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. enterica, L. mono, S. aureus | Broth | Sal: 7.3 × 101 CFU/mL Lm: 6.7 × 102 CFU/mL Sta: 6.9 × 102 CFU/mL | Simplex PCR | [11] |

| S. enterica, L. mono, S. aureus | Chicken meat samples | Sal: 7.3 × 104 CFU/mL Lm: 6.7 × 103 CFU/mL Sta: 6.9 × 102 CFU/mL | Simplex PCR |

| Sample Name | Salmonella Concentrations | Salmonella Counts Detected (CFUs/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| Eggs | 2.0 × 103 | 1885 |

| Eggs | 2.0 × 102 | 218 |

| Eggs | 2.0 × 101 | 21 |

| Chicken | 2.0 × 103 | 2070 |

| Chicken | 2.0 × 102 | 199 |

| Chicken | 2.0 × 101 | 21 |

| Spiked milk | 2.0 × 103 | 1975 |

| Spiked milk | 2.0 × 102 | 203 |

| Spiked milk | 2.0 × 101 | 20 |

| Actual Concentration log10 (CFU/mL) | Buffer | Chicken Broth | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calculated Concentration log10 (CFU/mL) | Recovery Rate | Calculated Concentration log10 (CFU/mL) | Recovery Rate | ||

| 2 | 1.97 | 98% | 1.75 | 88% | [82] |

| 3 | 2.87 | 96% | 2.77 | 92% | |

| 4 | 3.39 | 85% | 3.78 | 95% | |

| 5 | 4.44 | 89% | 4.80 | 96% | |

| 6 | 4.99 | 83% | 5.75 | 96% | |

| Type of Electrochemical Biosensor | Foodborne Pathogen | Food Matrix | Electrode Used | Electrode Modification | LOD | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phage-based electrochemical biosensors | S. Typhimurium | Skim milk and lettuce | GCE | RBP 41, carboxylated GO, AuNPs, BSA | 0.298 Log10 CFU/mL | [70] |

| Phage-based electrochemical biosensors | S. Typhimurium | Eggs, chicken, and milk | GDE | Phage L66, AuNPs, MPA, BSA | 21 CFU/mL | [83] |

| Antibody-based electrochemical biosensors | L. mono | Milk | GE | anti-L. mono Ab, L. mono cells, HRP-labelled rabbit polyclonal Ab | ≈7.5 CFU/mL | [74] |

| Nucleic Acid-Based Electrochemical Biosensors | S. Typhimurium | Pork, beef, mutton, donkey, dairy, and RTE egg products | GCE | Fc-hp, AuNPs | 2.08 fg·µL−1 | [78] |

| Nucleic Acid-Based Electrochemical Biosensors | L. mono | Fish meat | CILE | AuNPs, RGO, ssDNA/p | 3.17 × 10−14 mol/L (3S0/S) | [88] |

| Aptamer-Based Electrochemical Biosensors | L. mono | Lettuce and fresh-cut fruits | GCE | Si@MB, AuNPs, Apt, BSA | 2.6 CFU/mL | [90] |

| Cell-Based Electrochemical Biosensors | S. Typhimurium | Raw chicken | ITO | SsDNA, MWCNTs | 101 CFU/mL | [80] |

| Nanomaterials-Enhanced Electrochemical Biosensor | L. mono | Chicken broth | SPE | q-CNT, P100 Phage | 10 CFU/mL | [82] |

| Nanomaterials-Enhanced Electrochemical Biosensor | S. Typhimurium | Raw chicken | GCE | rGO, CNT, ssDNA | 101 CFU/mL | [81] |

| Target Pathogen | Technique | LOD (CFU/mL) | Time (minutes) | Specificity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salmonella | Molecular-PCR | 7.3 × 104 | - | High | [11] |

| Salmonella | Biosensor; Phage-based | 0.298 | 30 | High | [70] |

| L. mono | Molecular-PCR | 6.7 × 103 | - | High | [69] |

| L. mono | Molecular-ELISA | 1 | 100 | High | [12] |

| L. mono | Molecular-ELFA | 1 | 90 | High | [12] |

| L. mono | Biosensor; Phage-based | 8.4 | - | High | [77] |

| Salmonella | Biosensor; DNA-based | 2.08 µL−1 | - | High | [78] |

| L. mono | Spectroscopy-SERS | 1 × 105 | 30 | High | [65] |

| Salmonella | Immunological-LFA | 4.1 × 102 | - | High | [63] |

| L. mono | Biosensor-DNA-based | 2.6 | - | High | [90] |

| L. mono | Biosensor-DNA-based | 3.17 × 10−14 | - | High | [12] |

| S.enteritidis | Biosensor Nanomaterial enhanced | 6.7 × 101 | - | High | [77] |

| L. mono | Biosensor; Aptamer-based | 2.6 CFU/mL | 90 | High | [90] |

| Salmonella | Biosensor Nanomaterial enhanced | 101 | 10 | High | [78] |

| L. mono | Molecular-NGS | 107 | - | Low | [54] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ipeleng, K.E.; Feleni, U.; Saasa, V. Recent Developments on Salmonella and Listeria monocytogenes Detection Technologies: A Focus on Electrochemical Biosensing Technologies. Foods 2025, 14, 4139. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234139

Ipeleng KE, Feleni U, Saasa V. Recent Developments on Salmonella and Listeria monocytogenes Detection Technologies: A Focus on Electrochemical Biosensing Technologies. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4139. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234139

Chicago/Turabian StyleIpeleng, Keletso Eunice, Usisipho Feleni, and Valentine Saasa. 2025. "Recent Developments on Salmonella and Listeria monocytogenes Detection Technologies: A Focus on Electrochemical Biosensing Technologies" Foods 14, no. 23: 4139. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234139

APA StyleIpeleng, K. E., Feleni, U., & Saasa, V. (2025). Recent Developments on Salmonella and Listeria monocytogenes Detection Technologies: A Focus on Electrochemical Biosensing Technologies. Foods, 14(23), 4139. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234139