Effect of 1Bx7null on Soft Wheat Cookie Quality Under Different Nitrogen Inputs and Its CAPS Marker Development

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field Trials and Plant Materials

2.2. Quality Trait Testing

2.3. Baking Quality Test

2.4. Separation and Quantitation of Gluten Protein by SDS-PAGE and RP-HPLC

2.5. Nucleotide Sequence Analysis of 1Bx7 and 1Bx7null

2.6. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.7. Development of Cleaved Amplified Polymorphic Sequence (CAPS) Marker

2.8. CAPS Marker Validation

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

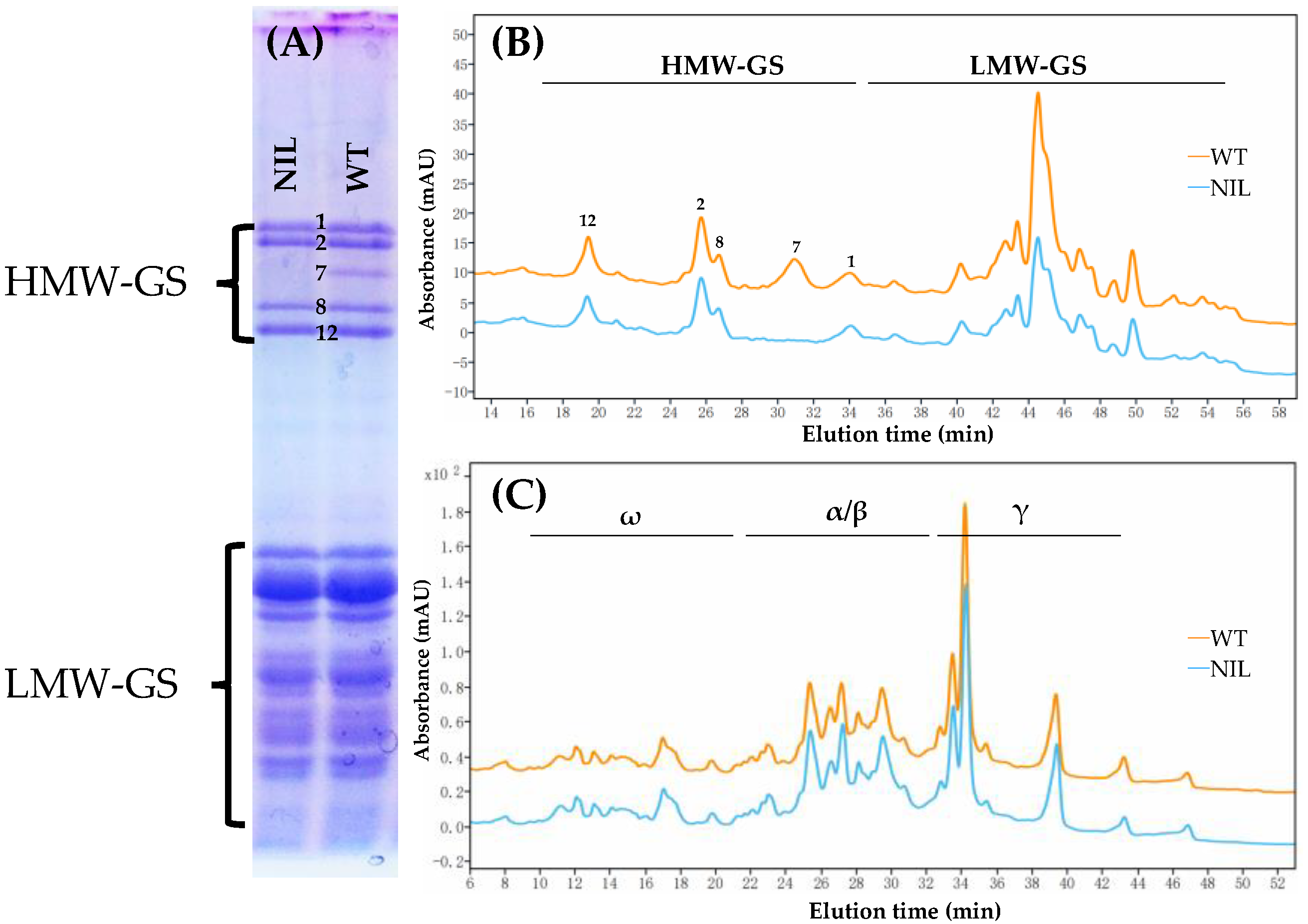

3.1. Composition of Gluten Proteins in WT and Its NIL

3.2. Comparative Analysis of Glu-B1x Genes from WT and Its NIL

3.3. Expression of the Glu-B1x Gene During the Grain Filling Stage

3.4. ANOVA of Agronomic Traits and Wheat Quality Traits

3.5. Grain Yield and Wheat Quality Traits in WT and NIL

3.6. Impact of Nitrogen Application Rates on Wheat Quality Traits

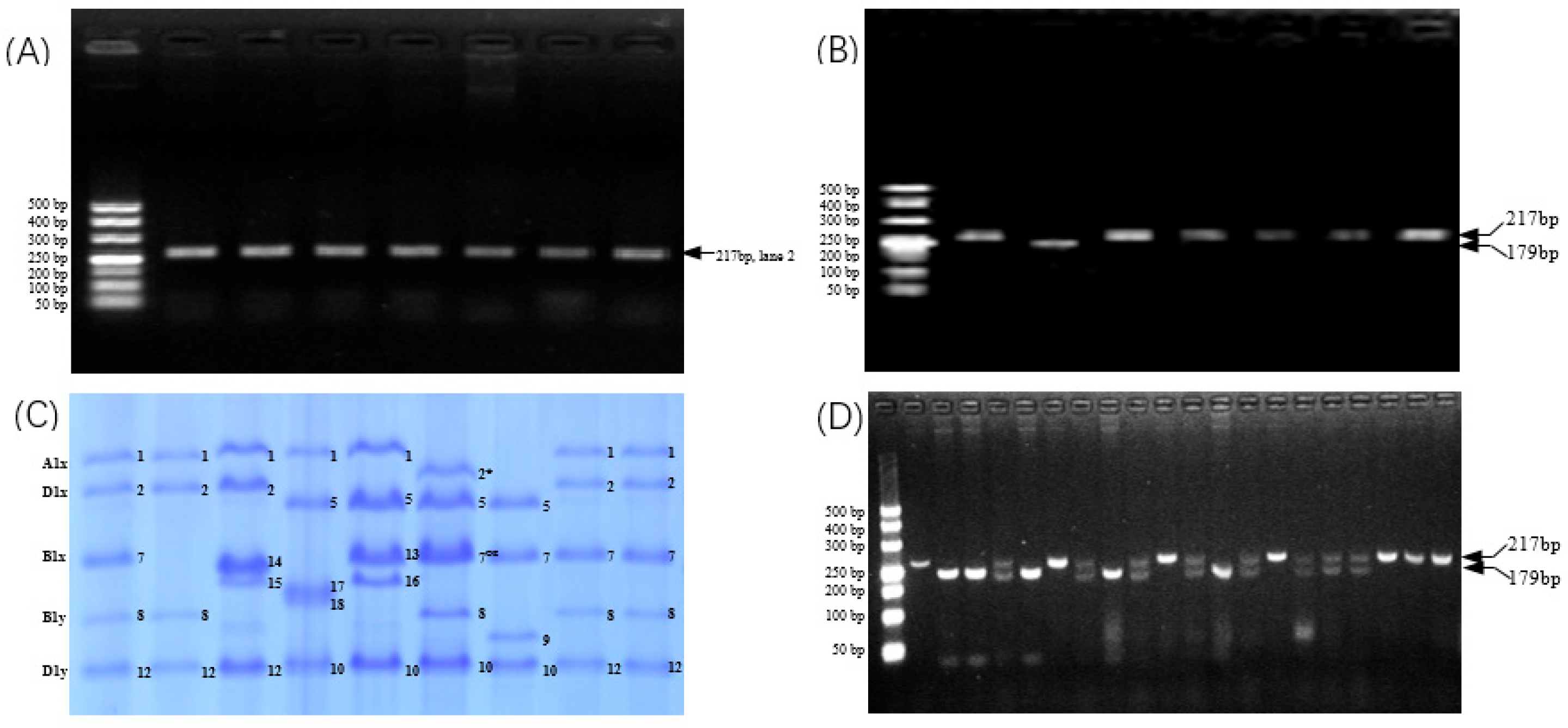

3.7. Development and Validation of CAPS Marker for 1Bx7null

4. Discussion

4.1. Investigation of the Genetic Background of Ningmai 9 WT and Its NIL

4.2. The Variation in Grain Yield and Quality Under Variable N Inputs

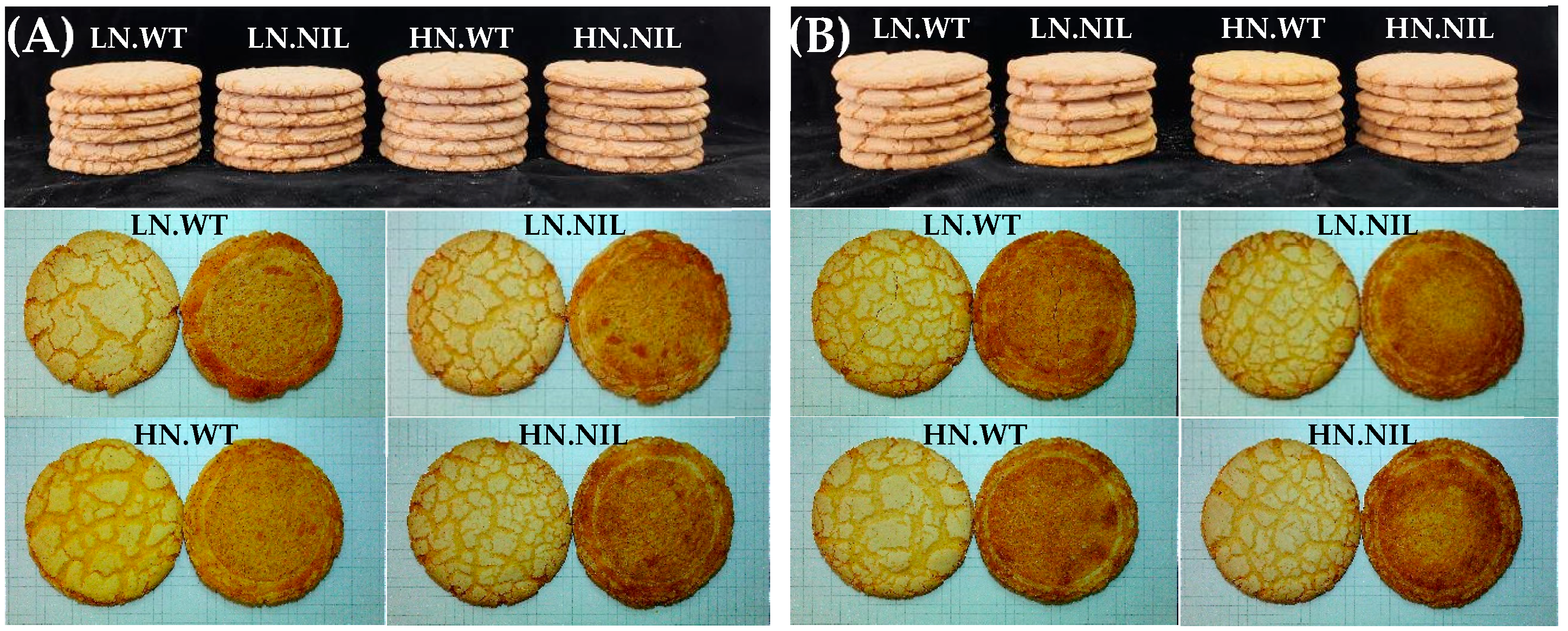

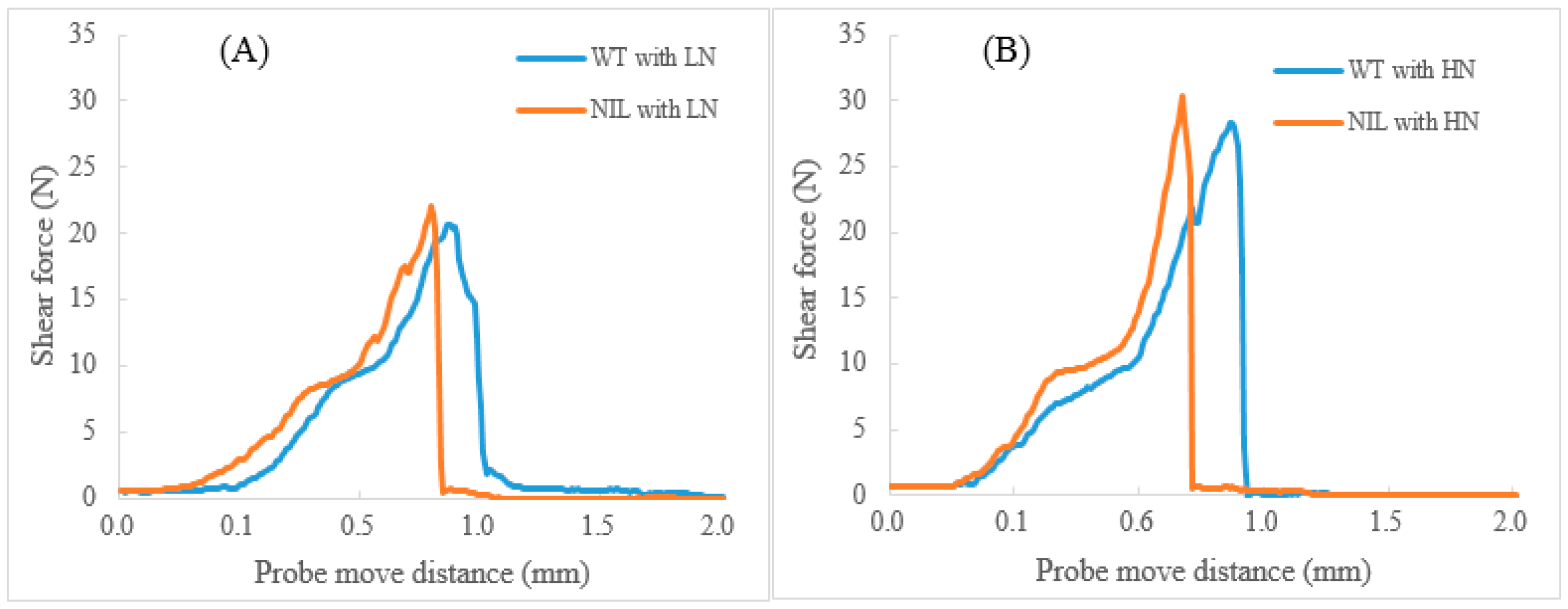

4.3. Effect of 1Bx7null on Dough Properties and Baking Quality

4.4. Development and Validation of CAPS Marker

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HMW-GS | High-molecular-weight glutenin subunit |

| HMW-GS | Low-molecular-weight glutenin subunit |

| LN | Low nitrogen |

| HN | High nitrogen |

| SNP | Single nucleotide polymorphism |

| WT | Wild type |

| NIL | Near isogenic line |

| CAPS | Cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence |

| CDS | Coding DNA sequence |

| NMD | Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay |

References

- Gianibelli, M.C.; Larroque, O.R. MacRitchie, F. Biochemical, genetic, molecular characterization of wheat glutenin and its component subunits. Cereal Chem. 2001, 78, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.P.; He, Z.H.; Chen, D.S.; Zhang, Y.; Larroque, O.R.; Xia, X.C. Contribution of common wheat protein fractions to dough properties and quality of northern-style Chinese steamed bread. J. Cereal Sci. 2007, 46, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.P.; Song, G.C.; Ibba, M.I.; Wang, H.D.; Ren, R.S. Dough properties and baking quality of near isogenic lines with single HMW-GS null at Glu-A1, Glu-B1 and Glu-D1 loci in soft wheat. LWT 2024, 213, 117084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.P.; Jondiko, T.O.; Tilley, M.; Awika, J.M. Effect of high molecular weight glutenin subunit composition in common wheat on dough properties and steamed bread quality. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 94, 2801–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, C.; Crossa, J.; Mondal, S.; Govindan, V.; Huerta, J.; Crespo-Herrera, L.; Vargas, M.; Singh, R.P.; Ibba, M.I. Effects of glutenins (Glu-1 and Glu-3) allelic variation on dough properties and bread-making quality of CIMMYT bread wheat breeding lines. Field Crop. Res. 2022, 284, 108585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.S.; Li, S.M.; Zhang, K.P.; Dong, Z.Y.; Li, Y.W.; An, X.L.; Chen, J.; Chen, Q.F.; Jiao, Z.; Liu, X.; et al. Efficient isolation of ion beam-induced mutants for homoeologous loci in common wheat and comparison of the contributions of Glu-1 loci to gluten functionality. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2014, 127, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.W.; An, X.L.; Yang, R.; Guo, X.M.; Yue, G.D.; Fan, R.C.; Bin, L.B.; Li, Z.S.; Zhang, K.P.; Dong, Z.Y.; et al. Dissecting and enhancing the contributions of high-molecular-weight glutenin subunits to dough functionality and bread quality. Mol. Plant 2015, 8, 332–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieser, H.; Zimmermann, G. Importance of amounts and proportions of high molecular weight subunits of glutenin for wheat quality. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2000, 210, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, E.J.; Sneller, C.; Guttieri, M.J.; Sturbaum, A.; Griffey, C.; Sorrells, M.; Ohm, H.; Van Sanford, D. Basis for selecting soft wheat for end-use quality. Crop Sci. 2012, 52, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiraghi, M.; Vanzetti, L.; Pflüger, L.; Helguera, M.; Pérez, G.T. Effect of high molecular weight glutenins and rye translocations on soft wheat flour cookie quality. J. Cereal Sci. 2013, 58, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.S.; Cadle, M.M. Effect of variation of Glu-D1 on club wheat end-use quality. Plant Breed. 1997, 116, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, F.R.; Bietz, J.A.; Nelsen, T.; Bains, G.S.; Finney, P.L. Soft wheat quality as related to protein composition. Cereal Chem. 1999, 76, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Kim, J.; Baika, B.K. Influences of high-molecular-weight glutenin subunits and rye translocations on dough-mixing properties and sugar-snap cookie-baking quality of soft winter wheat. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020, 100, 3850–3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, P.L.; Bains, G.S. Protein functionality differences in eastern U.S. soft wheat cultivars and interrelation with end-use quality tests. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 1999, 32, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; He, Z.H.; Peña, R.J. Effects of solvent retention capacities, pentosan content, and dough rheological properties on sugar snap cookie quality in Chinese soft wheat genotypes. Crop Sci. 2007, 47, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, B.Q.; Wu, H.Y.; Lu, C.B.; Lü, G.F.; Li, D.T.; Li, M.; Jiang, W.; Song, G.H.; Gao, D.R. Effect of high-molecular-weight glutenin subunit deletion on soft wheat quality properties and sugar-snap cookie quality estimated through near-isogenic lines. J. Integr. Agric. 2018, 17, 1066–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, W.J.; Gao, Y.J.; Yang, C.F.; Gao, X.; Peng, H.R.; Hu, Z.R.; Xin, M.M.; Ni, Z.F.; Zhang, P.P.; et al. High molecular weight glutenin subunits 1Bx7 and 1By9 encoded by Glu-B1 locus affect wheat dough properties and sponge cake quality. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 11796–11804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Guo, Z.R.; Chen, Q.; LI, Y.; Zhao, K.; Wan, Y.F.; Malcolm, J.H.; Jiang, Y.F.; Kong, L.; Pu, Z.E.; et al. Effect of high-molecular-weight glutenin subunit Dy10 on wheat dough properties and end-use quality. J. Integr. Agric. 2023, 22, 1609–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, S.; Khorshidi, A.S.; Scanlon, M.G. Relationship between nitrogen functionality and wheat flour dough rheology: Extensional and shear approaches. Food Res. Int. 2022, 162, 112049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Z.H.; Lin, Z.J.; Wang, L.J.; Xiao, Z.M.; Wan, F.S.; Zhuang, Q.S. Classification of Chinese wheat regions based on quality. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2002, 35, 359–364, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.Y.; Wang, Z.J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.C.; Hu, W.J.; Wang, H.; Gao, D.R.; Souza, E.; Cheng, S.H. Effects of different fertilizer treatments, environment and varieties on the yield-, grain-, flour-, and dough-related traits and cookie quality of weak-gluten wheat. Plants 2022, 11, 3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.Q.; Zhang, X.Q.; Li, W.Y.; Huang, M.; Zhou, Q.; Cai, J.; Wang, X.; Cao, W.X.; Dai, T.B.; Jiang, D. Increasing plant density improves grain yield, protein quality and nitrogen agronomic efficiency of soft wheat cultivars with reduced nitrogen rate. Field Crop. Res. 2021, 267, 108145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labuschagne, M.T.; Meintjes, G.; Groenewald, F.P.C. The influence of different nitrogen treatments on the size distribution of protein fractions in hard and soft wheat. J. Cereal Sci. 2006, 43, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AACC. Approved Methods of the American Association of Cereal Chemists, 10th ed.; AACC: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Peña, R.J.; Amaya, A.; Rajaram, S.; Mujeeb-Kazi, A. Variation in quality characteristics associated with some spring 1B/1R translocation wheats. J. Cereal Sci. 1990, 12, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; He, Z.H.; Yan, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, X.C.; Peña, R.J. Allelic variation at the Glu-1 and Glu-3 loci, presence of 1B.1R translocation, and their effects on mixographic properties in Chinese bread wheats. Euphytica 2005, 142, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larroque, O.R.; Gianibelli, M.C.; Sanchez, M.G.; MacRitchie, F. Procedure for obtaining stable protein extracts of cereal flour and whole meal for size-exclusion HPLC analysis. Cereal Chem. 2000, 77, 448–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, O.D.; Greene, F.C. The characterization and comparative analysis of high-molecular-weight glutenin genes from genomes A and B of a hexaploid bread wheat. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1989, 77, 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draper, S.R. ISTA variety committee-report of the working group for biochemical tests for cultivar identification 1983–1986. Seed Sci. Techno. 1987, 15, 431–434. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 17983-1999; High Quality Wheat–Weak Gluten Wheat. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 1999.

- GB/T 17320-2013; Quality Classification of Wheat Varieties. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2013.

- Fradgley, N.S.; Gardner, K.A.; Kerton, M.; Swarbreck, S.M.; Bentlety, A.R. Balancing quality with quantity: A case study of UK bread wheat. Plants People Planet 2024, 6, 1000–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.X.; Sun, L.J.; Zhou, G.Y.; Wu, L.N.; Lu, W.; Li, W.X.; Wang, S.; Yang, X.L.; Song, J.K.; Wang, B.J. Variations of wheat quality in China from 2006 to 2015. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2016, 49, 3063–3072, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Liu, D.T.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, D.R. Analysis of quality traits and breeding inspiration in Yangmai series wheat varieties. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2020, 53, 1309–1321, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, P.P.; Yao, J.B.; Wang, H.D.; Song, G.C.; Jiang, P.; Zhang, P.; Ma, H.X. Soft wheat quality traits in Jiangsu province and their relationship with cookie making quality. Acta Agron. Sin. 2020, 46, 491–502, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, C.; Peña, R.J.; Singh, R.; Autrique, E.; Dreisigacker, S.; Crossa, J.; Rutkoski, J.; Poland, J.; Battenfield, S. Wheat quality improvement at CIMMYT and the use of genomic selection on it. Appl. Transl. Genom. 2016, 29, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Jiang, J.L.; Zhou, Q.; Cai, J.; Wang, X.; Huang, M.; Zhong, Y.X.; Dai, T.B.; Cao, W.X.; Jiang, D. Analysis of American soft wheat grain quality and its suitability evaluation according to Chinese weak gluten wheat standard. Sci. Agric. Sin. 2022, 55, 3723–3737, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Gaines, C.S. Prediction of sugar-snap cookie diameter using sucrose solvent retention capacity, milling softness, and flour protein content. Cereal Chem. 2004, 81, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiraghi, M.; Vanzetti, L.; Bainotti, C.; Helguera, M.; León, A.; Pérez, G. Relationship between soft wheat flour physicochemical composition and cookie-making performance. Cereal Chem. 2011, 88, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, Q.; Cai, J.; Wang, X.; Cao, W.; Dai, T.; Jiang, D. Relationships of protein composition, gluten structure and dough rheological properties with short biscuits quality of soft wheat varieties. Agron. J. 2020, 112, 1921–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kweon, M.; Slade, L.; Levine, H.; Gannon, D. Cookie-versus cracker-Baking-What’s the difference? Flour functionality requirements explored by SRC and alveography. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. 2014, 54, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.Q.; Lia, S.J.; Liu, Y.W.; Liu, J.X.; Ma, X.L.; Du, L.P.; Wang, K.; Ye, X.G. Effects of 1Dy12 subunit silencing on seed storage protein accumulation and flour-processing quality in a common wheat somatic variation line. Food Chem. 2021, 335, 127663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.P.; Ma, H.X.; Yao, J.B.; Zhou, M.P.; Zhang, P. Effect of HMW-GS deletion on processing quality of soft wheat Ningmai 9. Acta Agron. Sin. 2016, 42, 633–640, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jondiko, T.O.; Alviola, N.J.; Hays, D.B.; Ibrahim, A.; Tilley, M.; Awika, J.M. Effect of high-molecular-weight glutenin subunit allelic composition on wheat flour tortilla quality. Cereal Chem. 2012, 89, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncil, Y.E.; Jondiko, T.; Tilley, M.; Hays, D.B.; Awika, J.M. Combination of null alleles with 7+9 allelic pair at Glu-B1 locus on the long arm of group 1 chromosome improves wheat dough functionality for tortillas. LWT 2016, 65, 683–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triboi, E.; Abad, A.; Michelena, A.; Lloveras, J.; Ollier, J.L.; Daniel, C. Environmental effects on the quality of two wheat genotypes: 1. Quantitative and qualitative variation of storage proteins. Eur. J. Agron. 2000, 13, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, C.S.; Peterson, C.J.; Ross, A.S.; Ohm, J.B.; Verhoeven, M.C.; Larson, M.; Hoefer, B. Winter wheat genotypes under different levels of nitrogen and water stress: Changes in grain protein composition. J. Cereal Sci. 2008, 47, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genotype | Glu-A1x | Glu-B1x | Glu-B1y | Glu-D1x | Glu-D1y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIL | 1 | Null | 8 | 2 | 12 |

| WT | 1 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 12 |

| Lumai 23 | 1 | 14 | 15 | 2 | 12 |

| Ninghongmai 529 | 1 | 17 | 18 | 5 | 10 |

| Wanmai 33 | 1 | 13 | 19 | 5 | 10 |

| Glenlea | 2* | 7OE | 8 | 5 | 10 |

| Yangmai 22 | 0 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 10 |

| Ningmai 14 | 1 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 12 |

| Ningmai 18 | 1 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, P.; Song, G.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, J. Effect of 1Bx7null on Soft Wheat Cookie Quality Under Different Nitrogen Inputs and Its CAPS Marker Development. Foods 2025, 14, 4137. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234137

Zhang P, Song G, Zhang Y, Yao J. Effect of 1Bx7null on Soft Wheat Cookie Quality Under Different Nitrogen Inputs and Its CAPS Marker Development. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4137. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234137

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Pingping, Guicheng Song, Yuntao Zhang, and Jinbao Yao. 2025. "Effect of 1Bx7null on Soft Wheat Cookie Quality Under Different Nitrogen Inputs and Its CAPS Marker Development" Foods 14, no. 23: 4137. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234137

APA StyleZhang, P., Song, G., Zhang, Y., & Yao, J. (2025). Effect of 1Bx7null on Soft Wheat Cookie Quality Under Different Nitrogen Inputs and Its CAPS Marker Development. Foods, 14(23), 4137. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234137