Rediscovering Olive Mill Wastewater: New Chemical Insights Through Untargeted UHPLC-QTOF-MS Data-Dependent Analysis Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical and Reagents

2.2. Samples and Samples Preparation

2.3. UHPLC-QTOF Untargeted Acquisition

2.4. Data Elaboration

2.5. Statistical Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

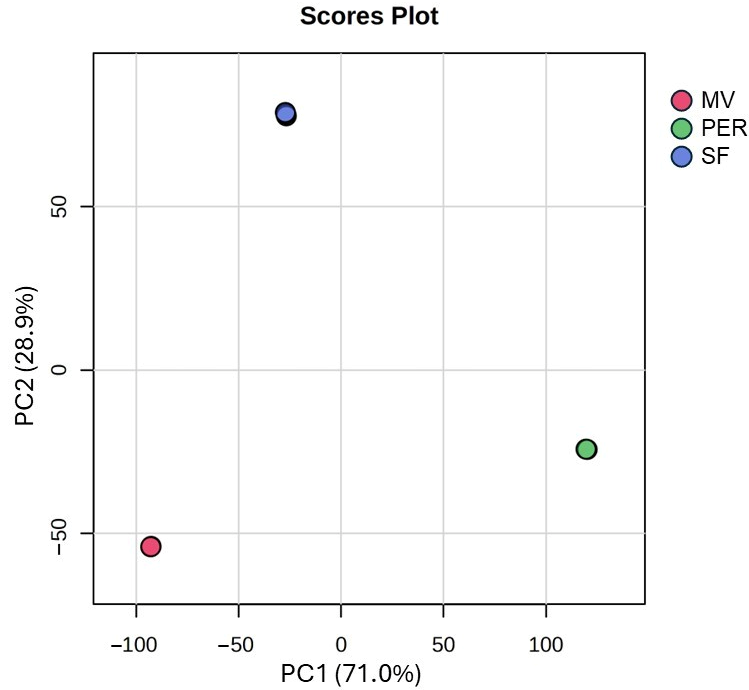

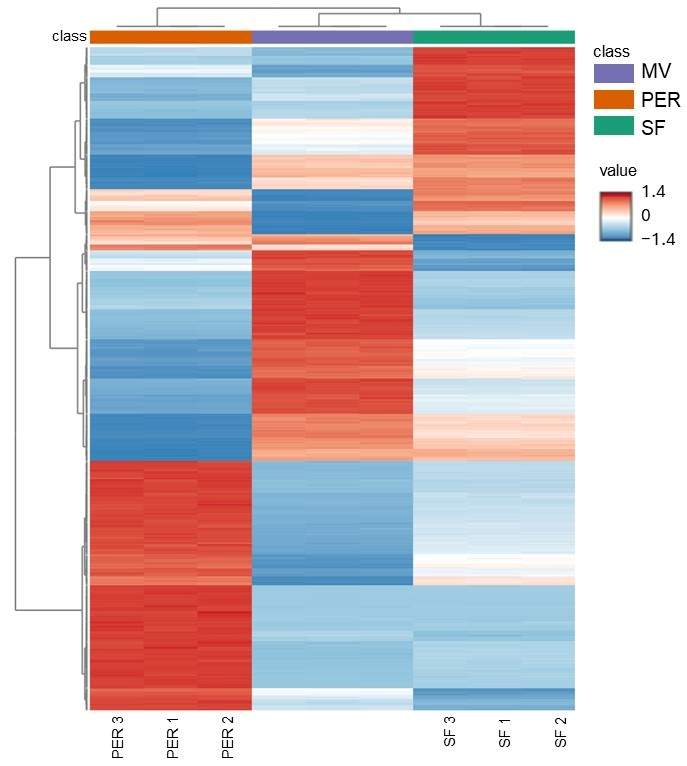

3.1. Unknown Features: PCA and Heatmap

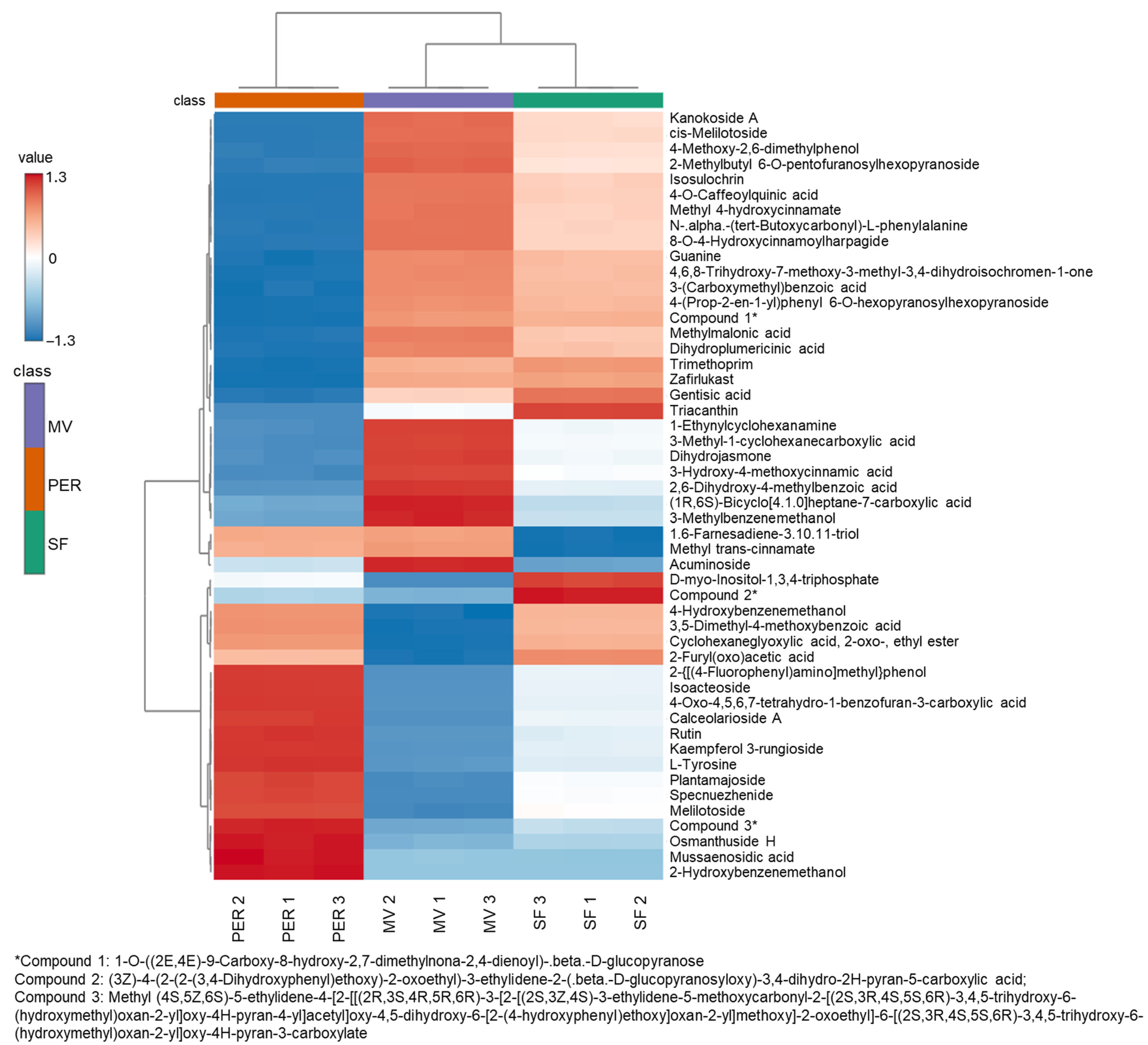

3.2. MS/MS Compound Annotation

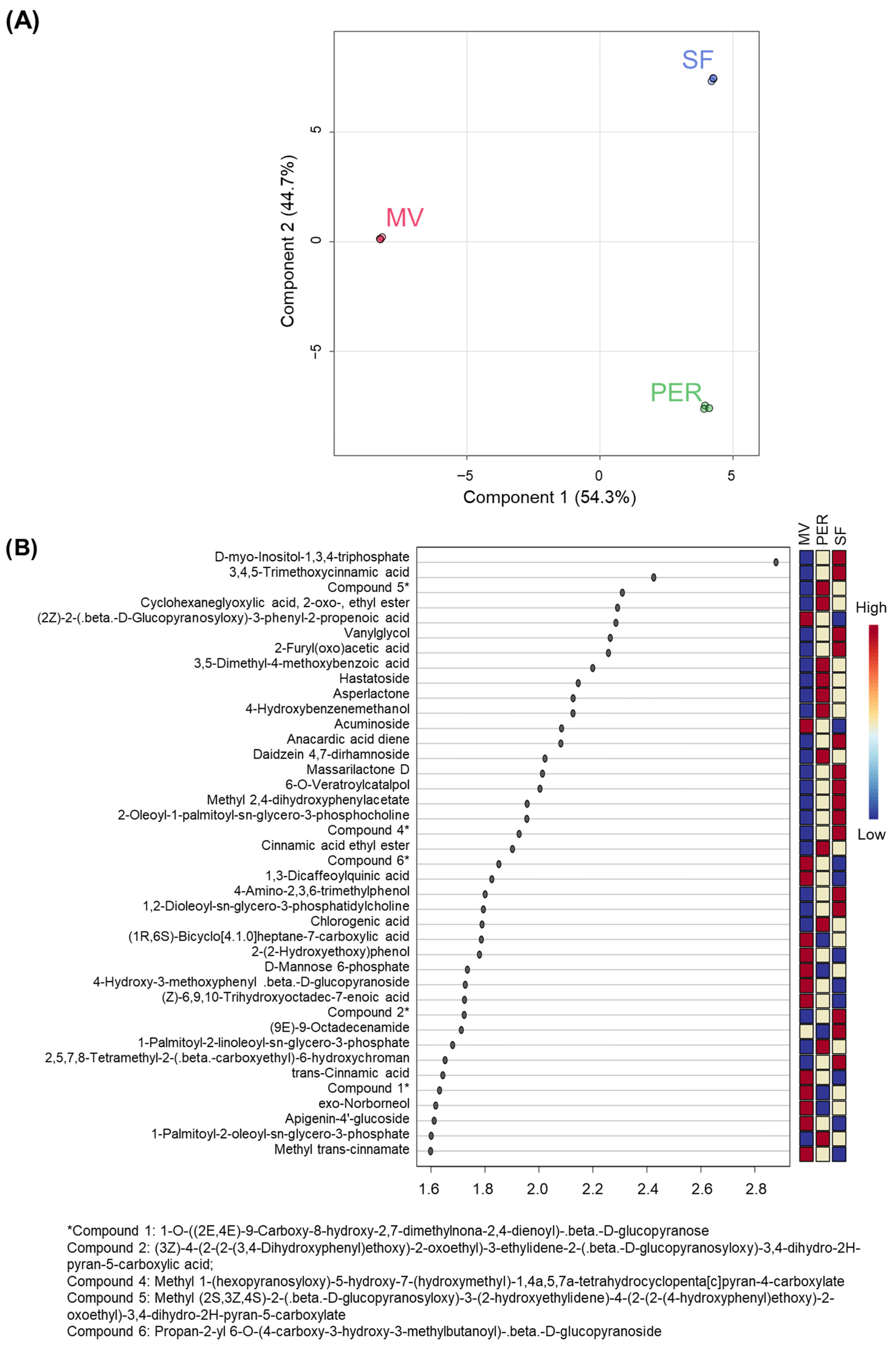

3.3. OMWW Sample Discrimination

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OMWW | Olive mill wastewater |

| EVOO | Extra-virgin olive oil |

| PER | Samples from Peranzana olive cultivar |

| SF | Samples from Sargano di Fermo olive cultivar |

| MV | Samples from multivarietal oil production |

| DDA | Data-dependent analysis |

| TIC | Total ion chromatogram |

| PLS-DA | Partial least squares–discriminant analysis |

| VIP | Variables important in projection |

| PCA | Principal components analysis |

References

- FAO. Crops. FaoStat. 2020. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/?#data/QC (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Caprioli, G.; Boarelli, M.C.; Ricciutelli, M.; Sagratini, G.; Fiorini, D. Micro-scaled quantitative method to analyze olive oil polyphenols. Food Anal. Methods 2019, 12, 1133–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciutelli, M.; Marconi, S.; Boarelli, M.C.; Caprioli, G.; Sagratini, G.; Ballini, R.; Fiorini, D. Olive oil polyphenols: A quantitative method by high-performance liquid-chromatography-diode-array detection for their determination and the assessment of the related health claim. J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1481, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, T.A.; Masoodi, F.; Gani, A.; Baba, W.N.; Rahmanian, N.; Akhter, R.; Wani, I.A.; Ahmad, M. Olive oil and its principal bioactive compound: Hydroxytyrosol—A review of the recent literature. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 77, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Difonzo, G.; Troilo, M.; Squeo, G.; Pasqualone, A.; Caponio, F. Functional compounds from olive pomace to obtain high-added value foods—A review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraskeva, P.; Diamadopoulos, E. Technologies for olive mill wastewater (OMW) treatment: A review. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. Int. Res. Process Environ. Clean Technol. 2006, 81, 1475–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, L.C.; Vilhena, A.M.; Novais, J.M.; Martins-Dias, S. Olive mill wastewater characteristics: Modelling and statistical analysis. Grasas y Aceites 2004, 55, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Abbassi, A.; Kiai, H.; Hafidi, A. Phenolic profile and antioxidant activities of olive mill wastewater. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 406–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamrah, A.; Al-Zghoul, T.M.; Darwish, M.M. A comprehensive review of combined processes for olive mill wastewater treatments. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2023, 8, 100493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabir, S.; Ilyas, N.; Saeed, M.; Bibi, F.; Sayyed, R.; Almalki, W.H. Treatment technologies for olive mill wastewater with impacts on plants. Environ. Res. 2023, 216, 114399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahi, M.R.; Zam, W.; El Hattab, M. State of knowledge on chemical, biological and nutritional properties of olive mill wastewater. Food Chem. 2022, 381, 132238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Long, H.; Deng, Y.; Li, S.; Xi, Y.; Li, W.; Cai, H.; Zhang, B. Emerging LC-MS/MS-based molecular networking strategy facilitates foodomics to assess the function, safety, and quality of foods: Recent trends and future perspectives. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 139, 104114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés, A.; Alvarez-Rivera, G.; Socas-Rodríguez, B.; Herrero, M.; Ibanez, E.; Cifuentes, A. Foodomics: Analytical opportunities and challenges. Anal. Chem. 2021, 94, 366–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciutelli, M.; Angeloni, S.; Conforti, S.; Corneli, M.; Caprioli, G.; Sagratini, G.; Alabed, H.B.; D’Amato Tóthová, J.; Pellegrino, R.M. An untargeted metabolomics approach to study changes of the medium during human cornea culture. Metabolomics 2024, 20, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, G.; Hui, F.; Xu, L.; Viau, C.; Spigelman, A.F.; MacDonald, P.E.; Wishart, D.S.; Li, S.; et al. MetaboAnalyst 6.0: Towards a unified platform for metabolomics data processing, analysis and interpretation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W398–W406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mauro, M.D.; Giardina, R.C.; Fava, G.; Mirabella, E.F.; Acquaviva, R.; Renis, M.; D’Antona, N. Polyphenolic profile and antioxidant activity of olive mill wastewater from two Sicilian olive cultivars: Cerasuola and Nocellara etnea. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2017, 243, 1895–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviani, I.; Raviv, M.; Hadar, Y.; Saadi, I.; Dag, A.; Ben-Gal, A.; Yermiyahu, U.; Zipori, I.; Laor, Y. Effects of harvest date, irrigation level, cultivar type and fruit water content on olive mill wastewater generated by a laboratory scale ‘Abencor’ milling system. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 107, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salek, R.M.; Steinbeck, C.; Viant, M.R.; Goodacre, R.; Dunn, W.B. The role of reporting standards for metabolite annotation and identification in metabolomic studies. Gigascience 2013, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, S.; Guo, H.; Jiang, H.; Liu, H.; Fu, H.; Wang, D. Forsythoside a mitigates alzheimer’s-like pathology by inhibiting ferroptosis-mediated neuroinflammation via Nrf2/GPX4 axis activation. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 18, 2075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Qian, J.; Li, Y.; Meng, Y.; Cheng, R.; Ren, N.; Fei, Y. Protective effects of forsythoside A against severe acute pancreatitis-induced brain injury in mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 178, 117301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shiekh, R.A.; Saber, F.R.; Abdel-Sattar, E.A. In vitro anti-hypertensive activity of Jasminum grandiflorum subsp. floribundum (Oleaceae) in relation to its metabolite profile as revealed via UPLC-HRMS analysis. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2020, 1158, 122334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, S.M.; Falcão, S.I.; Peres, A.M.; Domingues, M.R. Oleuropein/ligstroside isomers and their derivatives in Portuguese olive mill wastewaters. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brien, S.; Lewith, G.T.; McGregor, G. Devil’s Claw (Harpagophytum procumbens) as a treatment for osteoarthritis: A review of efficacy and safety. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2006, 12, 981–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parenti, C.; Arico, G.; Pennisi, M.; Alessandro, V.; Scoto, G.M. Harpagophytum procumbens extract potentiates morphine antinociception in neuropathic rats. Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 30, 1248–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrara, M.; Kelly, M.T.; Roso, F.; Larroque, M.; Margout, D. Potential of Olive Oil Mill Wastewater as a Source of Polyphenols for the Treatment of Skin Disorders: A Review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 7268–7284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benincasa, C.; Pellegrino, M.; Romano, E.; Claps, S.; Fallara, C.; Perri, E. Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Phenolic Compounds in Spray-Dried Olive Mill Wastewater. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 782693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guvem, S.A.; Ozbey-Unal, B.; Keskinler, B.; Balcik, C. Redefining the waste: Sustainable management of olive mill waste for the recovery of phenolic compounds and organic acids. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 68, 106343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir-Cerdà, A.; Granados, M.; Saurina, J.; Sentellas, S. Olive tree leaves as a great source of phenolic compounds: Comprehensive profiling of NaDES extracts. Food Chem. 2024, 456, 140042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Márquez, J.M.; Navarro-Hortal, M.D.; Forbes-Hernández, T.Y.; Varela-López, A.; Puentes, J.G.; Sánchez-González, C.; Sumalla-Cano, S.; Battino, M.; García-Ruiz, R.; Sánchez, S.; et al. Effect of olive leaf phytochemicals on the anti-acetylcholinesterase, anti-cyclooxygenase-2 and ferric reducing antioxidant capacity. Food Chem. 2024, 444, 138516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-González, R.; Juan, M.E.; Planas, J.M. Table olive polyphenols: A simultaneous determination by liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2020, 1609, 460434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Aloy, M.; Groff, N.; Masuero, D.; Nisi, M.; Franco, A.; Battelini, F.; Vrhovsek, U.; Mattivi, F. Exploratory analysis of commercial olive-based dietary supplements using untargeted and targeted metabolomics. Metabolites 2020, 10, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baoyi, F.; Shaojie, F.; Xiaoping, S.; Tiantian, G.; Yan, S.; Yanxin, Z.; Qingchao, L. The oleoside-type secoiridoid glycosides: Potential secoiridoids with multiple pharmacological activities. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1283, 135286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermúdez-Oria, A.; Castejón, M.L.; Rubio-Senent, F.; Fernández-Prior, Á.; Rodríguez-Gutiérrez, G.; Fernández-Bolaños, J. Isolation and structural determination of cis- and trans-p-coumaroyl-secologanoside (comselogoside) from olive oil waste (alperujo). Photoisomerization with ultraviolet irradiation and antioxidant activities. Food Chem. 2024, 432, 137233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borghini, F.; Tamasi, G.; Loiselle, S.A.; Baglioni, M.; Ferrari, S.; Bisozzi, F.; Costantini, S.; Tozzi, C.; Riccaboni, A.; Rossi, C. Phenolic Profiles in Olive Leaves from Different Cultivars in Tuscany and Their Use as a Marker of Varietal and Geographical Origin on a Small Scale. Molecules 2024, 29, 3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oku, H.; Ogawa, Y.; Iwaoka, E.; Ishiguro, K. Allergy-preventive effects of chlorogenic acid and iridoid derivatives from flower buds of Lonicera japonica. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2011, 34, 1330–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, I.; Hisada, S.; Nishibe, S. Lignan glycosides of Trachelospermum asiaticum var. intermedium. Phytochemistry 1971, 10, 211–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingaki, I.; Hisada, S.; Nishibe, S. Lignans of Trachelospermum asiaticum var. intermedium. I. Isolation and structures of arctiin, matairesinoside and tracheloside. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1972, 20, 2710–2718. [Google Scholar]

- Khammar, A.; Djeddi, S. Pharmacological and biological properties of some Centaurea species. Eur. J. Sci. Res. 2012, 84, 398–416. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Geng, R.; Chen, Y.; Qin, J.; Guo, S. Matairesinoside, a novel inhibitor of TMEM16A ion channel, loaded with functional hydrogel for lung cancer treatment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 264, 130618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geana, E.-I.; Ciucure, C.T.; Apetrei, I.M.; Clodoveo, M.L.; Apetrei, C. Discrimination of Olive Oil and Extra-Virgin Olive Oil from Other Vegetable Oils by Targeted and Untargeted HRMS Profiling of Phenolic and Triterpenic Compounds Combined with Chemometrics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khodakov, G. Triterpene and steroidal glycosides of the genus Melilotus and their genins. VI. Melilotoside A2 and adzukisaponin v from the roots of M. tauricus. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2013, 48, 1024–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablikim, G.; Bobakulov, K.; Li, J.; Yadikar, N.; Aisa, H.A. Two new glucoside derivatives of truxinic and cinnamic acids from Lavandula angustifolia mill. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 2526–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayrakçeken Güven, Z.; Saracoglu, I.; Nagatsu, A.; Yilmaz, M.A.; Basaran, A.A.; D’Abbadie, F. Anti-tyrosinase and antimelanogenic effect of cinnamic acid derivatives from Prunus mahaleb L.: Phenolic composition, isolation, identification and inhibitory activity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 310, 116378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, S.; Zeng, T.; Sun, L.; Yin, M.; Wu, P.; Ma, P.; Xu, L.; Xiao, P. The effect of vine tea (Ampelopsis grossedentata) extract on fatigue alleviation via improving muscle mass. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 325, 117810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santanatoglia, A.; Angeloni, S.; Caprioli, G.; Fioretti, L.; Ricciutelli, M.; Vittori, S.; Alessandroni, L. Comprehensive investigation of coffee acidity on eight different brewing methods through chemical analyses, sensory evaluation and statistical elaboration. Food Chem. 2024, 454, 139717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, P.; Kumar, N.; Singh, B.; Kaul, V.K. Simultaneous determination of sugars and picrosides in Picrorhiza species using ultrasonic extraction and high-performance liquid chromatography with evaporative light scattering detection. J. Chromatogr. A 2008, 1194, 257–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Dong, W.; Wang, Y.; Gong, L.; Dai, Z.; Cheung, H.-Y. Pipette tip solid-phase extraction and ultra-performance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry based rapid analysis of picrosides from Picrorhiza scrophulariiflora. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2013, 80, 136–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, D.; Grover, A. “Picrosides” from Picrorhiza kurroa as potential anti-carcinogenic agents. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 109, 1680–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, M.; Guo, C.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, R.; Peng, C. A review of pharmacological and pharmacokinetic properties of stachydrine. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 155, 104755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Li, P.; Liu, P.; Xu, P. Exploring stachydrine: From natural occurrence to biological activities and metabolic pathways. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1442879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Tang, Y.; Li, B.; Tang, J.; Xu, H.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, X. Stachydrine, a potential drug for the treatment of cardiovascular system and central nervous system diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 161, 114489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Bhandari, R.; Brearley, C.A.; Saiardi, A. The inositol phosphate signalling network in physiology and disease. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2024, 49, 969–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riemer, E.; Pullagurla, N.J.; Yadav, R.; Rana, P.; Jessen, H.J.; Kamleitner, M.; Schaaf, G.; Laha, D. Regulation of plant biotic interactions and abiotic stress responses by inositol polyphosphates. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 944515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chamkha, M.; Garcia, J.-L.; Labat, M. Metabolism of cinnamic acids by some Clostridiales and emendation of the descriptions of Clostridium aerotolerans, Clostridium celerecrescens and Clostridium xylanolyticum. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2001, 51, 2105–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggoun, M.; Arhab, R.; Cornu, A.; Portelli, J.; Barkat, M.; Graulet, B. Olive mill wastewater microconstituents composition according to olive variety and extraction process. Food Chem. 2016, 209, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Rt (min) | Experimental m/z | Metabolite Name | Adduct Type | Reference m/z | Formula | InChIKey | Total Score 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9.52 | 642.2386, 625.2128, 325.0931, 471.1500, 623.2021 | Isoacteoside | [M+H−C14H20O7]+, [M+H−C8H10O3]+, [M+NH4]+, [M+H]+, [M−H]− | 642.2392, 625.2127, 325.0918, 471.1497, 623.1981 | C29H36O15 | FNMHEHXNBNCPCI-QEOJJFGVSA-N | 97.4; 84.0; 74.0; 69.0; 87.3 |

| 13.25 | 177.0559 | Jaslanceoside B | [M−H−C16H20O11]− | 177.0557 | C26H30O14 | MGEVYVDQMTWJNV-HOPHSATRSA-N | 97.0 |

| 5.61 | 403.1263 | Oleoside 11-methyl ester | [M−H]− | 403.1246 | C17H24O11 | XSCVKBFEPYGZSL-JYVCFIOWSA-N | 95.3 |

| 8.30 | 163.0407 | 8-O-4-Hydroxycinnamoylharpagide | [M−H−C15H22O9]− | 163.0401 | C24H30O12 | AZKQDXZMKREFDY-LGKDJQOASA-N | 94.2 |

| 2.67 | 461.1675 | Verbasoside | [M−H]− | 461.1664 | C20H30O12 | DORPKYRPJIIARM-GYAWPQPFSA-N | 93.9 |

| 3.87 | 389.1140 | Secologanoside | [M−H]− | 389.1089 | C16H22O11 | RGTONEMDTVVDMY-UHFFFAOYSA-N | 93.8 |

| 2.88 | 114.1029 | 1-Pyrrolidinecarboximidamide | [M+H]+ | 114.1026 | C5H11N3 | PIGIRWPZTWLVLB-UHFFFAOYSA-N | 93.1 |

| 1.54 | 124.0393 | Nicotinic acid | [M+H]+ | 124.0393 | C6H5NO2 | PVNIIMVLHYAWGP-UHFFFAOYSA-N | 92.5 |

| 4.17 | 107.0495 | 4-Hydroxybenzenemethanol | [M+H−H2O]+ | 107.0491 | C7H8O2 | BVJSUAQZOZWCKN-UHFFFAOYSA-N | 92.3 |

| 1.40 | 195.0533 | D-Gluconic acid | [M−H]− | 195.0510 | C6H12O7 | RGHNJXZEOKUKBD-SQOUGZDYSA-N | 92.0 |

| 5.45 | 193.0863 | Sinapyl alcohol | [M+H−H2O]+ | 193.0859 | C11H14O4 | LZFOPEXOUVTGJS-ONEGZZNKSA-N | 92.0 |

| 8.30 | 119.0501 | cis-Melilotoside | [M−H−C7H10O7]− | 119.0502 | C15H18O8 | GVRIYIMNJGULCZ-QLFWQTQQSA-N | 91.9 |

| 5.61 | 807.2576, 403.1248, 243.0867 | (3-Ethenyl-2-(.β.-D-glucopyranosyloxy)-5-(methoxycarbonyl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-pyran-4-yl)acetic acid | [M+H−C6H10O5]+, [2M−H]−, [M−H]− | 807.2564, 403.1246, 243.0863 | C17H24O11 | MQLSOVRLZHTATK-WNCYHATQSA-N | 91.8; 87.4; 82.3 |

| 10.51 | 193.0548 | Picroside III | [M−H−C15H20O9]− | 193.0506 | C25H30O13 | RMSKZOXJAHOIER-GGKKSNITSA-N | 91.8 |

| 10.95 | 447.0933 | Luteolin 7-glucoside | [M−H]− | 447.0933 | C21H20O11 | PEFNSGRTCBGNAN-QNDFHXLGSA-N | 91.5 |

| 5.74 | 583.2034 | 4-((3R,4S)-4-Hydroxy-4-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzyl)-3-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-2-methoxyphenyl .β.-D-glucopyranoside | [M+CHO2]− | 583.2033 | C26H34O12 | OXHVZEZYYQQCRJ-ZLNFVOGTSA-N | 91.4 |

| 3.26 | 345.1215 | Salidroside | [M+CHO2]− | 345.1191 | C14H20O7 | ILRCGYURZSFMEG-RKQHYHRCSA-N | 90.9 |

| 3.16 | 329.0881, 659.1824 | 4-(Hexopyranosyloxy)-3-methoxybenzoic acid | [M−H]−, [2M−H]− | 329.0878, 659.1829 | C14H18O9 | JYFOSWJYZIVJPO-UHFFFAOYSA-N | 90.8; 82.2 |

| 5.80 | 179.0418 | 4-O-Caffeoylquinic acid | [M−H−C7H10O5]− | 179.0350 | C16H18O9 | GYFFKZTYYAFCTR-JUHZACGLSA-N | 90.8 |

| 1.78 | 295.1035 | 4-(.β.-D-Glucopyranosyloxy)benzyl 3-(.β.-D-glucopyranosyloxy)-2-(((2Z)-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)prop-2-enoyl)oxy)-3-methylbutanoate | [M−H−C22H22O8]− | 295.1035 | C33H42O17 | LZXXRASHAINSDN-ZLFKWPTHSA-N | 90.7 |

| 1.52 | 144.1056 | Stachydrine | [M+H]+ | 144.1019 | C7H13NO2 | CMUNUTVVOOHQPW-UHFFFAOYSA-N | 90.6 |

| 3.30 | 197.0813 | 4-(2-Methyl-6-oxopyran-3-yl)butanoic acid | [M+H]+ | 197.0808 | C10H12O4 | QFJCZUUIDDALPA-UHFFFAOYSA-N | 90.5 |

| 6.28 | 415.1610, 461.1748, 434.2024, 439.1574 | 2-Phenylethyl 2-O-.β.-D-xylopyranosyl-.β.-D-glucopyranoside | [M−CHO2]−, [M+NH4]+, [M+Na]+, [M−H]− | 415.1610, 461.1665, 434.2021, 439.1575 | C19H28O10 | CGZNTHDUAFIKOH-BMVMOQKNSA-N | 90.2; 82.0; 81.4; 71.6 |

| 5.11 | 171.1021 | 3-Cyclohexyl-3-oxopropanoic acid ethyl ester | [M+H−C2H4]+ | 171.1016 | C11H18O3 | ASYASKBLHYSMEG-UHFFFAOYSA-N | 90.0 |

| 6.66 | 181.0497 | Caffeic acid | [M+H]+ | 181.0495 | C9H8O4 | QAIPRVGONGVQAS-DUXPYHPUSA-N | 90.0 |

| 4.25 | 651.1934, 325.0939 | Melilotoside | [M−H]−, [2M−H]− | 651.1931, 325.0929 | C15H18O8 | GVRIYIMNJGULCZ-ZMKUSUEASA-N | 90.0; 87.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alessandroni, L.; Ricciutelli, M.; Angeloni, S.; Caprioli, G.; Sagratini, G. Rediscovering Olive Mill Wastewater: New Chemical Insights Through Untargeted UHPLC-QTOF-MS Data-Dependent Analysis Approach. Foods 2025, 14, 4128. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234128

Alessandroni L, Ricciutelli M, Angeloni S, Caprioli G, Sagratini G. Rediscovering Olive Mill Wastewater: New Chemical Insights Through Untargeted UHPLC-QTOF-MS Data-Dependent Analysis Approach. Foods. 2025; 14(23):4128. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234128

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlessandroni, Laura, Massimo Ricciutelli, Simone Angeloni, Giovanni Caprioli, and Gianni Sagratini. 2025. "Rediscovering Olive Mill Wastewater: New Chemical Insights Through Untargeted UHPLC-QTOF-MS Data-Dependent Analysis Approach" Foods 14, no. 23: 4128. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234128

APA StyleAlessandroni, L., Ricciutelli, M., Angeloni, S., Caprioli, G., & Sagratini, G. (2025). Rediscovering Olive Mill Wastewater: New Chemical Insights Through Untargeted UHPLC-QTOF-MS Data-Dependent Analysis Approach. Foods, 14(23), 4128. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14234128