1. Introduction

Peach (

Prunus persica L.) is valued for its distinctive flavor and nutritional richness [

1]. It contains vitamins, dietary fiber, minerals, and bioactive compounds, which contributes to its widespread consumption worldwide [

2]. As consumer expectations for fruit quality continue to rise, the market demand for high-quality peaches has increased. However, the peach industry still faces challenges of inconsistent fruit quality and imbalances between supply and demand, which underscores the importance of efficient quality control. Fruit quality is commonly evaluated based on appearance, flavor, texture, and nutritional value [

3]. Appearance encompasses visual traits such as size, shape, color, and surface integrity. Flavor, a more complex attribute, results from the interplay of sweetness, acidity, bitterness, astringency, and aromatic compounds. Texture refers to the mechanical and structural properties perceived through tactile and oral sensations. Among these quality indicators, firmness is a key texture attribute used to evaluate peach maturity, sensory quality, and postharvest shelf life [

4]. Therefore, the development of rapid, nondestructive techniques for measuring firmness is essential for accurate fruit grading and supply chain optimization.

The acoustic vibration response of fruit is closely related to its internal physical properties [

5], providing a viable approach for firmness assessment. In mechanical terms, fruit can be modeled as a vibration system consisting of mass and elastic components [

6]. By analyzing dynamic response characteristics, such as resonance frequency and vibration attenuation under external excitation, key mechanical properties of the system can be derived. Abbott et al. [

7] pioneered the use of acoustic vibration technology for evaluating apple firmness and introduced the elasticity index

EI =

f22m, where

f2 is the second resonance frequency and

m is the mass of the sample. Since then, acoustic vibration technology has been widely applied to assess various fruit quality attributes, including firmness [

8], internal decay [

9], and split-pit defects [

10].

A typical acoustic vibration detection system comprises an excitation unit, a signal acquisition unit, and a signal processing module. Commonly used excitation methods include tapping [

11], electromagnetic shaker [

12], loudspeaker [

13], and laser-induced plasma (LIP) [

14]. Among these, tapping is simple to perform but may cause mechanical damage; an electromagnetic shaker offers stable output but lacks portability; loudspeaker and LIP enable noncontact excitation but are limited by insufficient excitation intensity or sensitivity to environmental interference. In 2024, a noncontact excitation method based on an air jet was proposed [

15], which was suitable for in-field vibration testing of peaches on the tree. This method features a short action time, a controllable impact force, and non-destructiveness, demonstrating considerable potential for indoor applications.

The acquisition of acoustic vibration signals primarily relies on contact sensors (e.g., accelerometers, piezoelectric sensors) and noncontact sensors (e.g., microphones, laser Doppler vibrometers) [

16]. Although contact sensors are commonly used in practice, their added mass may alter the fruit’s natural vibration behavior. Zhang et al. [

17] developed a wearable acoustic device for predicting kiwifruit firmness using the stiffness index, which showed a good correlation with sensory firmness. In contrast, noncontact methods are more suitable for high-throughput detection. Kataoka et al. [

18] assessed tomato firmness using a speaker–microphone system, but this approach was susceptible to ambient noise. The laser Doppler vibrometer (LDV), known for its high resolution and wide dynamic range [

19], enables precise measurement of fruit surface vibrations. Furthermore, with recent advances in artificial intelligence, deep learning models have shown considerable potential in feature extraction and modeling of acoustic vibration signals and have been successfully applied to predicting the postharvest quality of fruits [

20,

21]. However, the generalization capability and prediction accuracy of deep learning models are often limited when applied across different cultivars or growing conditions due to biological variability and signal inconsistency. Most existing models are developed for specific cultivars and lack generalizability, which limits their broad adoption in the fruit industry.

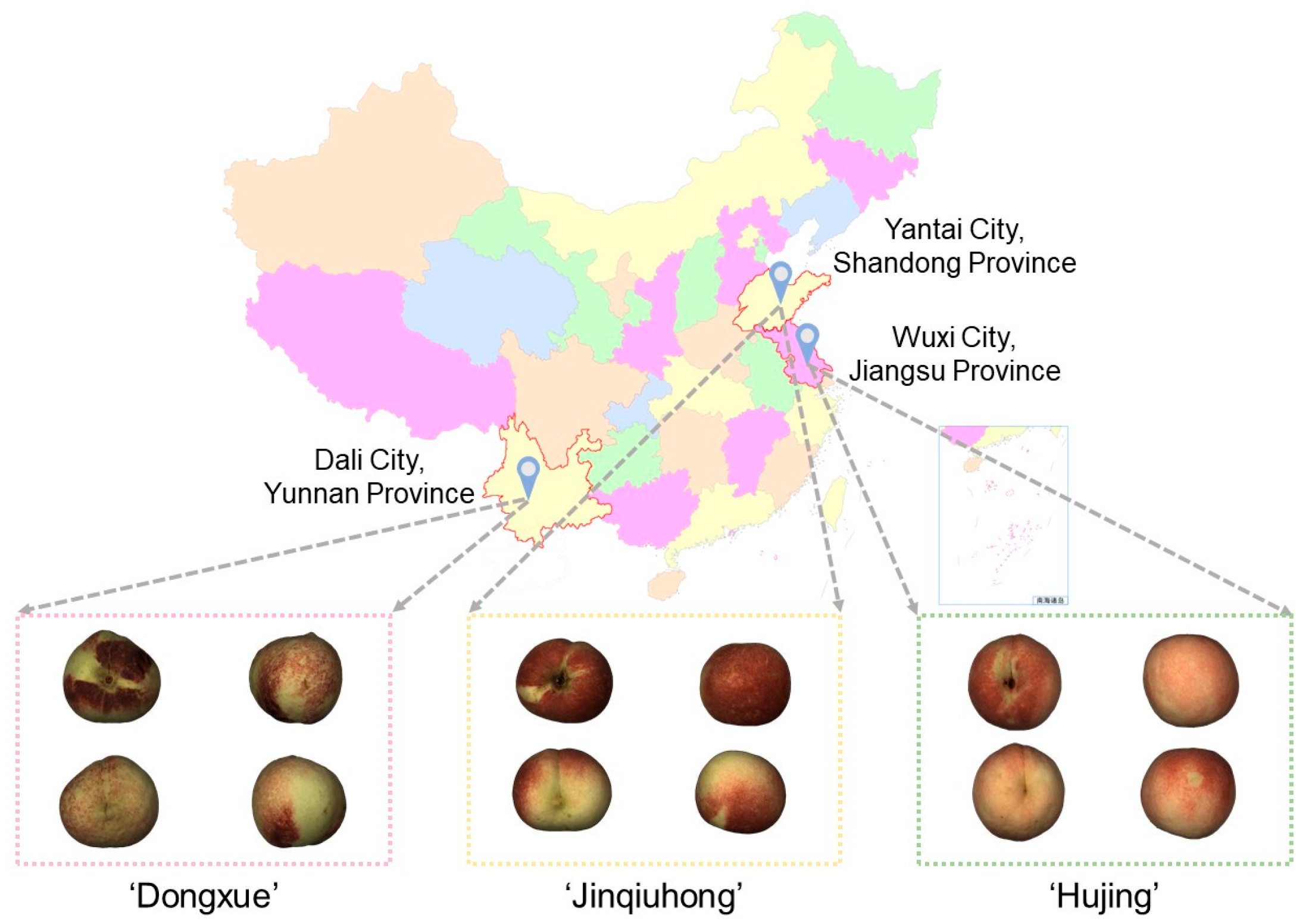

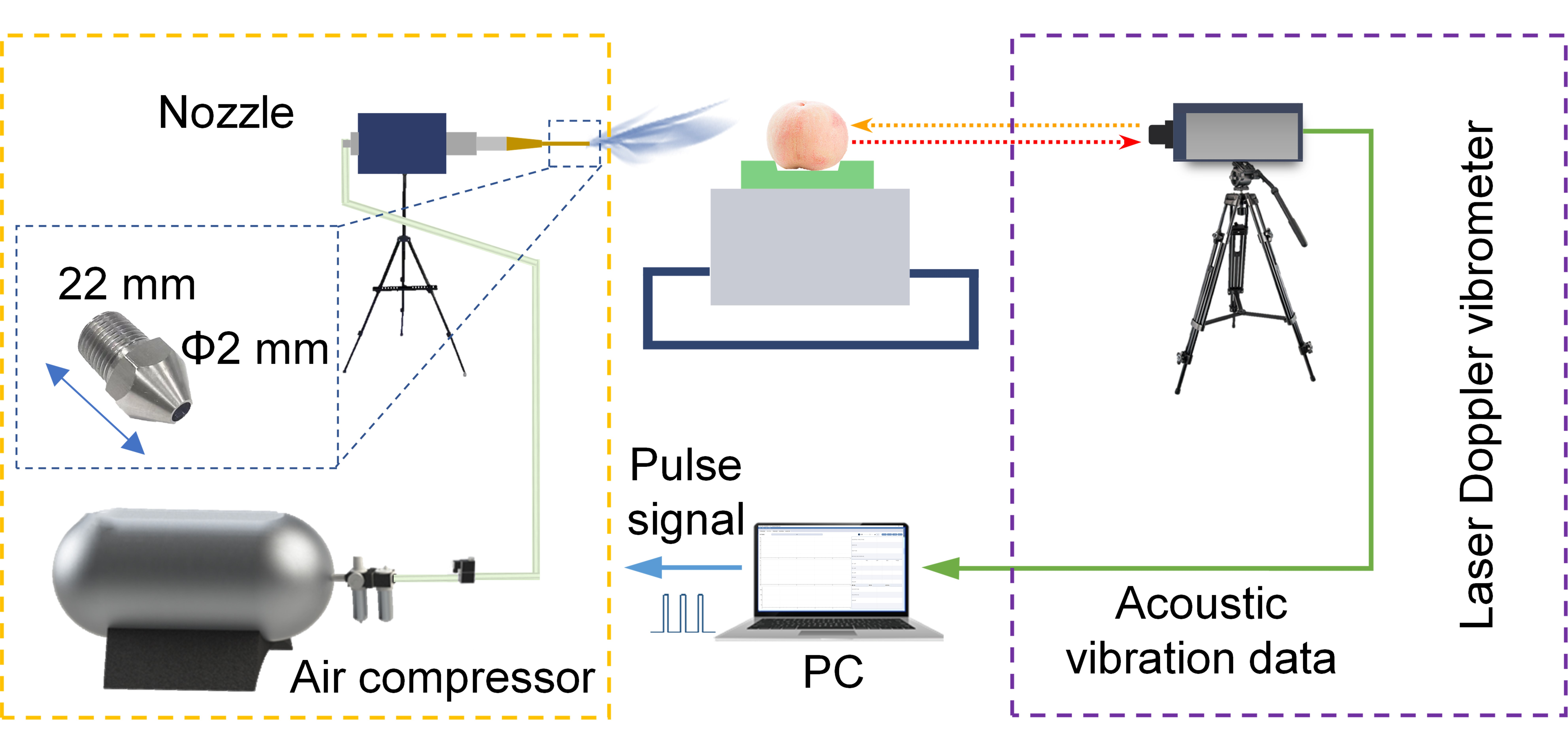

To achieve rapid, nondestructive, and accurate firmness evaluation across multiple peach cultivars, this study proposes a noncontact acoustic vibration method with deep learning algorithms to construct a cross-cultivar firmness prediction model. The specific objectives are (1) to develop a noncontact acoustic vibration signal acquisition system that combines an air jet and an LDV; (2) to analyze commonalities and differences in acoustic vibration characteristics across different peach cultivars; (3) to propose a deep learning framework for cross-cultivar firmness assessment based on acoustic vibration spectra; and (4) to explore a transfer learning-based strategy for model updating, providing a practical pathway to enhance generalizability across new cultivars.

3. Results

3.1. Statistical Analysis of Acoustic Vibration Spectra and Peach Firmness

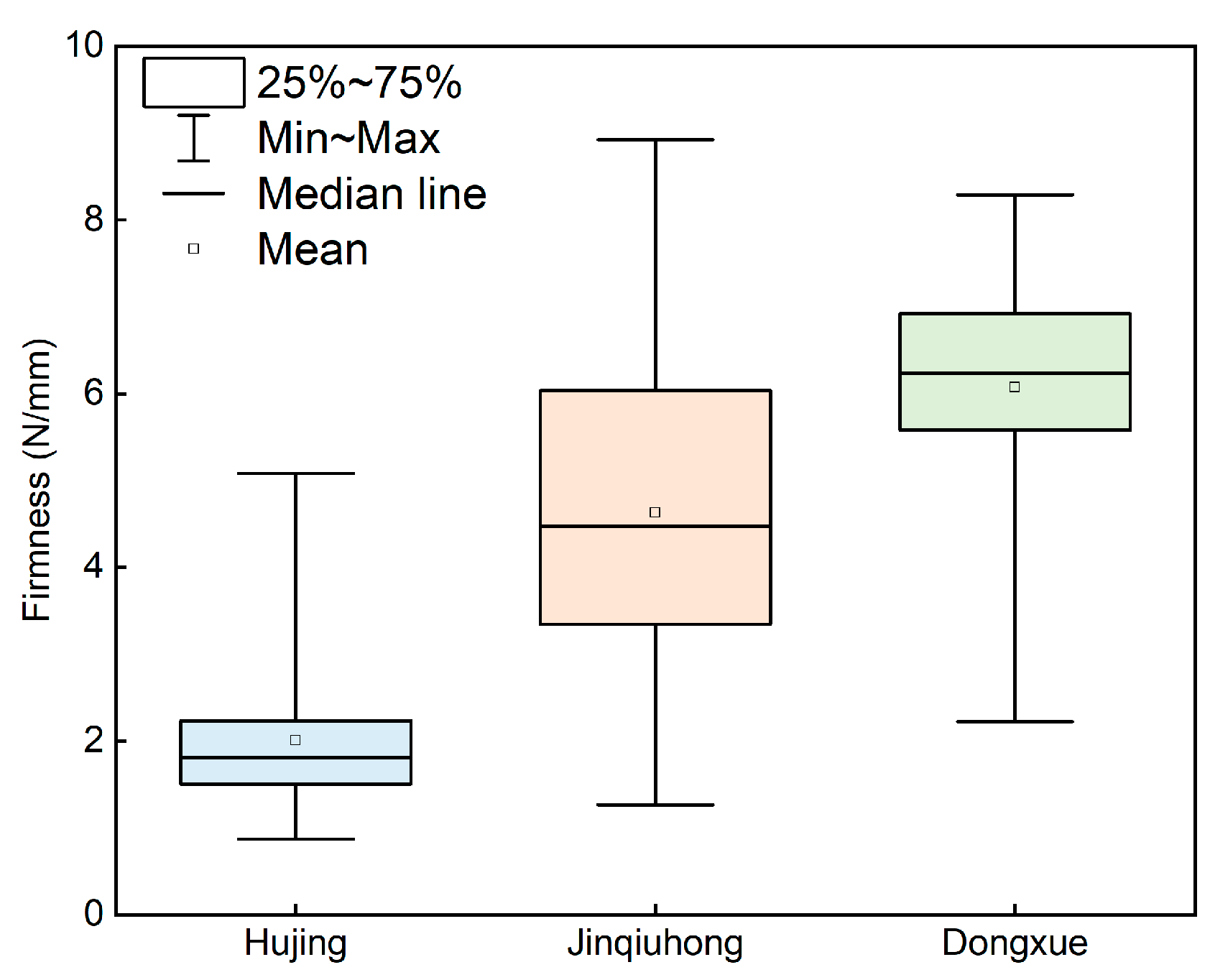

The statistical results of reference firmness values for three peach cultivars are shown in

Figure 6. The data revealed a discernible gradient in firmness among the cultivars. Hujing exhibited the lowest firmness with a mean value of 2.01 N/mm, and its values were predominantly clustered within the lower range of 0.87–5.08 N/mm. Jinqiuhong displayed intermediate firmness with a mean value of 4.63 N/mm and exhibited the widest distribution range among the three cultivars (1.26–8.92 N/mm). In contrast, Dongxue demonstrated the highest firmness with a mean value of 6.07 N/mm, and its lower limit was notably higher than that of the other cultivars (2.22–8.29 N/mm).

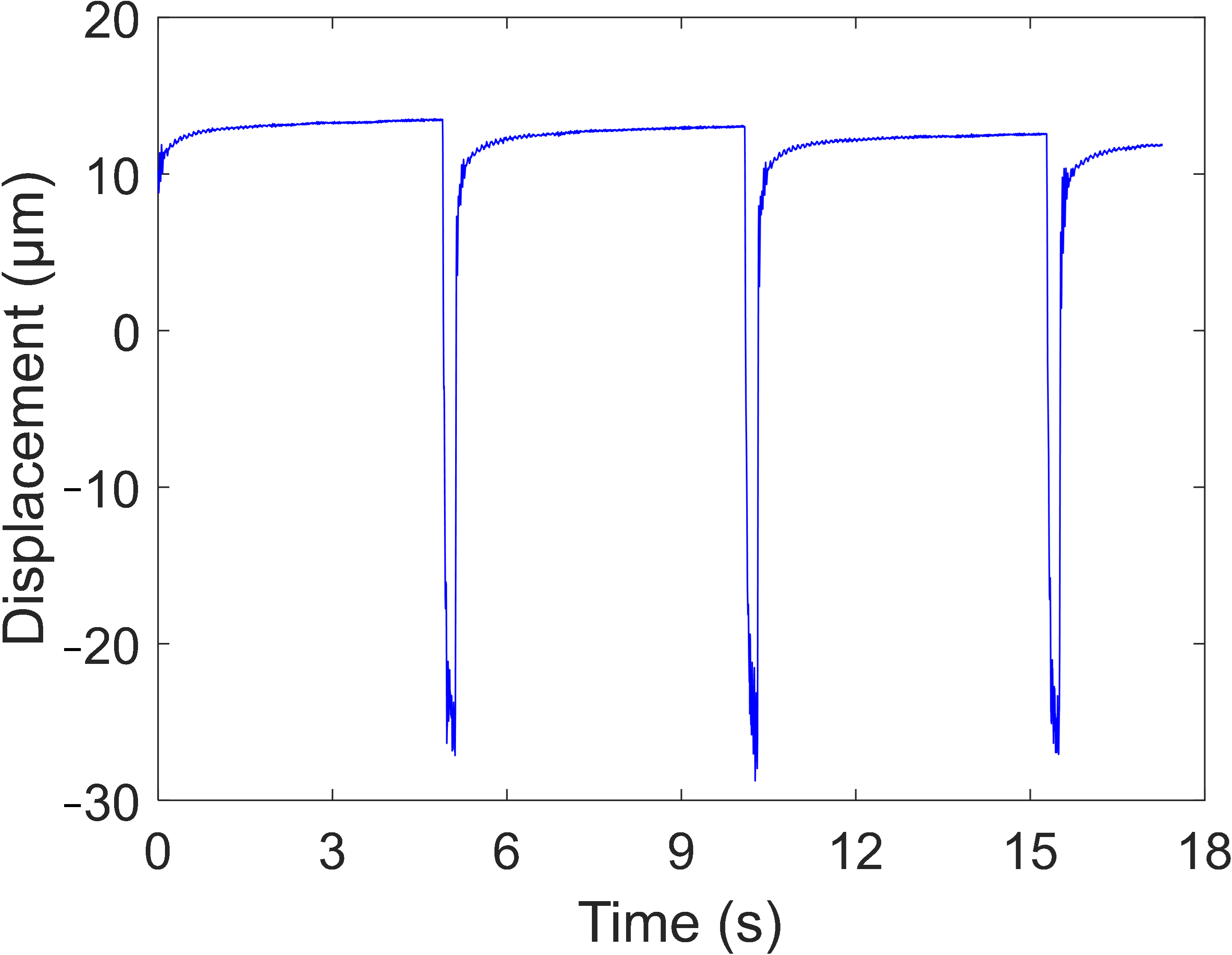

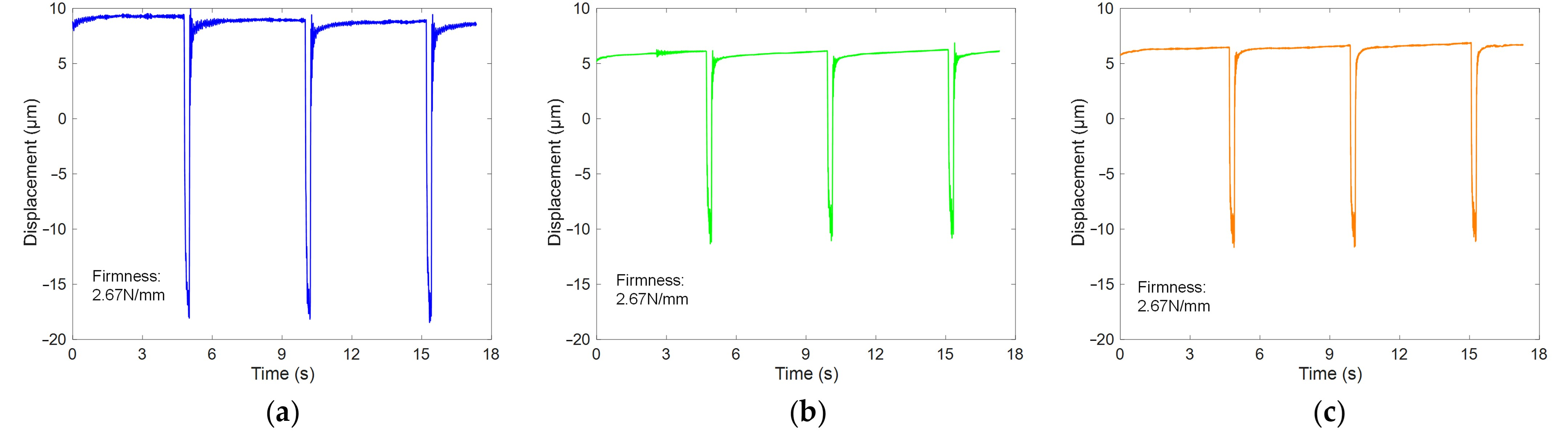

Figure 7 displays representative time-domain response signals and their corresponding firmness values for the ‘Hujing’, ‘Jinqiuhong’, and ‘Dongxue’ peach cultivars, as measured by the developed system. The results indicated that the system effectively induced vibrational responses in peaches across three cultivars. However, comparative analysis revealed significant differences in vibration peak amplitudes among the cultivars, even when their firmness values were similar. These findings demonstrated that time-domain features, such as signal amplitude, could not reliably characterize fruit firmness. Therefore, to better extract firmness-related features of the fruit, subsequent analysis was shifted to the frequency domain.

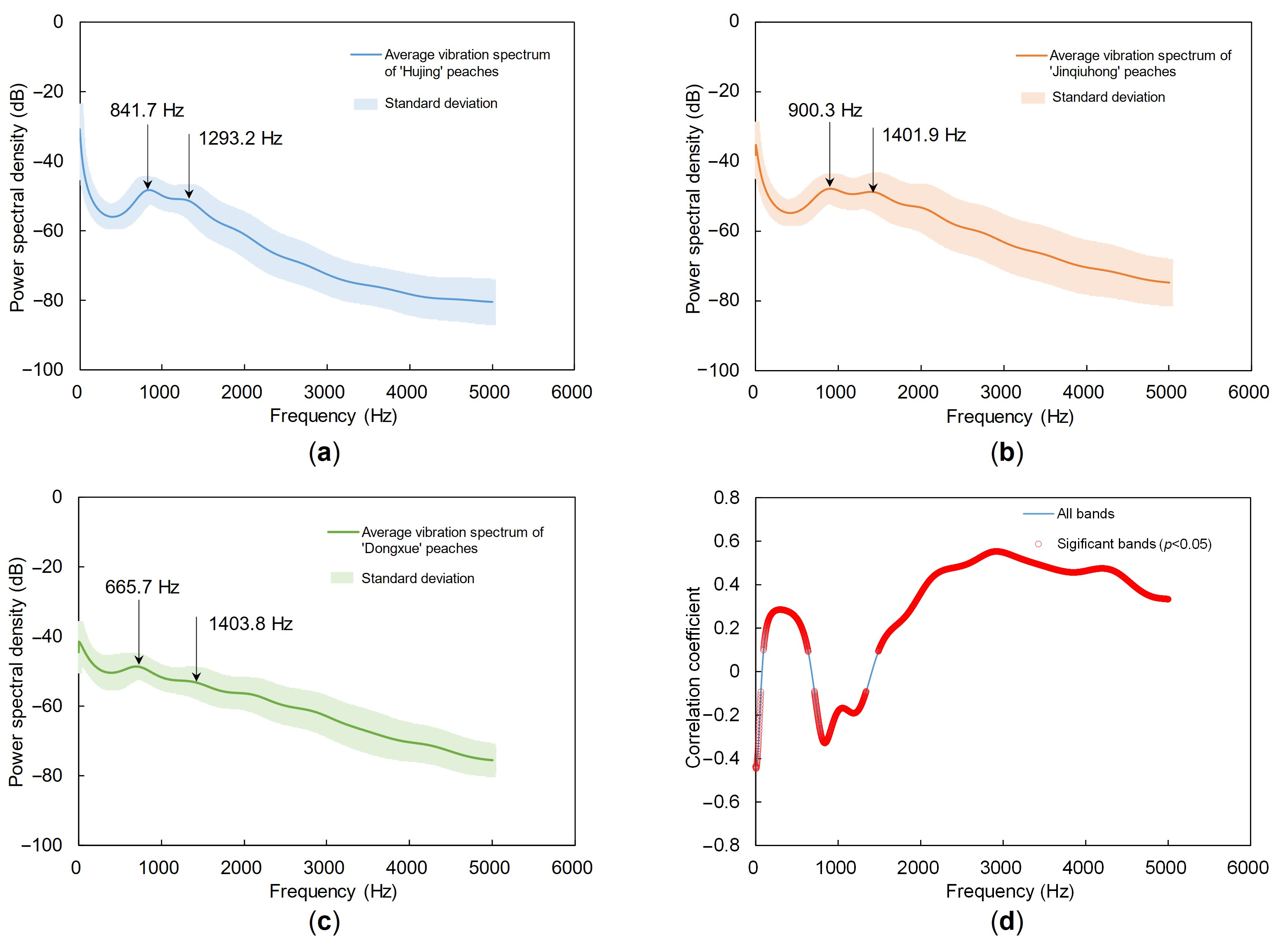

The average PSDs of Hujing, Jinqiuhong, and Dongxue peaches are presented in

Figure 8. The first and second resonant frequencies were identified as 841.7 Hz and 1293.2 Hz for Hujing, 900.3 Hz and 1401.9 Hz for Jinqiuhong, and 665.7 Hz and 1403.8 Hz for Dongxue, respectively. Notably, Dongxue showed the lowest first resonant frequency despite having the highest firmness, deviating from the generally anticipated positive correlation between firmness and resonant frequency. The results indicated that the relationship between firmness and resonant frequency was not straightforward and can be cultivar-dependent. This discrepancy may be attributed to the complex internal structure and anisotropic mechanical properties of peaches. Resonant frequency is influenced not only by firmness but also by multiple factors, including cultivar, size, shape, density, and internal architecture. The complex interactions among these factors may lead to a non-monotonic relationship between firmness and resonant frequency across different cultivars.

A correlation analysis was conducted between the full PSDs and firmness across all samples. As shown in

Figure 8d, the correlation exhibited clear frequency-dependent behavior. In the 0–70 Hz and 700–1300 Hz ranges, correlation coefficients were generally negative, indicating that vibration amplitude decreased with increasing firmness. In contrast, above 1500 Hz, the correlation coefficients became positive and increased with frequency, reaching approximately 0.55 near 3000 Hz. These patterns suggested that low-frequency responses were more affected by mass and damping properties, resulting in a negative correlation with firmness, whereas high-frequency responses were more sensitive to tissue elasticity, leading to a positive correlation. The frequency band near 3000 Hz, which showed the highest correlation with firmness, did not coincide with the resonant peaks of the three cultivars. Therefore, prediction models relying solely on resonant frequencies or specific parameters may have limited generalizability when applied across cultivars with distinct physical properties. In conclusion, utilizing full PSDs as model inputs supports the development of more robust and transferable firmness prediction models that are less dependent on cultivar-specific characteristics.

3.2. Multi-Cultivar PLSR and SVR Models for Peach Firmness Prediction

Table 2 summarizes the prediction results of peach firmness using PLSR, SVR, and ISNet-1D models with full PSDs as inputs. Overall, the SVR model exhibited superior predictive performance and robustness over the PLSR model. During modeling, the optimal number of latent variables for the PLSR model was set to 49 by minimizing the RMSE of the validation set. The key hyperparameters of the SVR model were obtained using the Bayesian optimizer, including a linear kernel, a box constraint of 0.0109, and an epsilon value of 0.0086.

On the calibration set, the SVR model achieved a higher

of 0.7111 and a lower RMSEC of 1.1260 N/mm than the PLSR model (

= 0.6665, RMSEC = 1.1812 N/mm), indicating better fitting performance. Moreover, the RPDC of the SVR model (1.8706) also exceeded that of the PLSR model (1.7338), reflecting greater model stability. For the test set, the

, RMSEP, and

of the SVR model were 0.6827, 1.1277 N/mm, and 1.8161, respectively. The

, RMSEP, and

of the PLSR model were 0.6546, 1.2312 N/mm, and 1.7107, respectively. In summary, using full PSDs as inputs, the SVR model surpassed PLSR in predicting peach firmness. However, as the RPD values of both models remained below 2.0, there was still potential for further enhancing predictive performance.

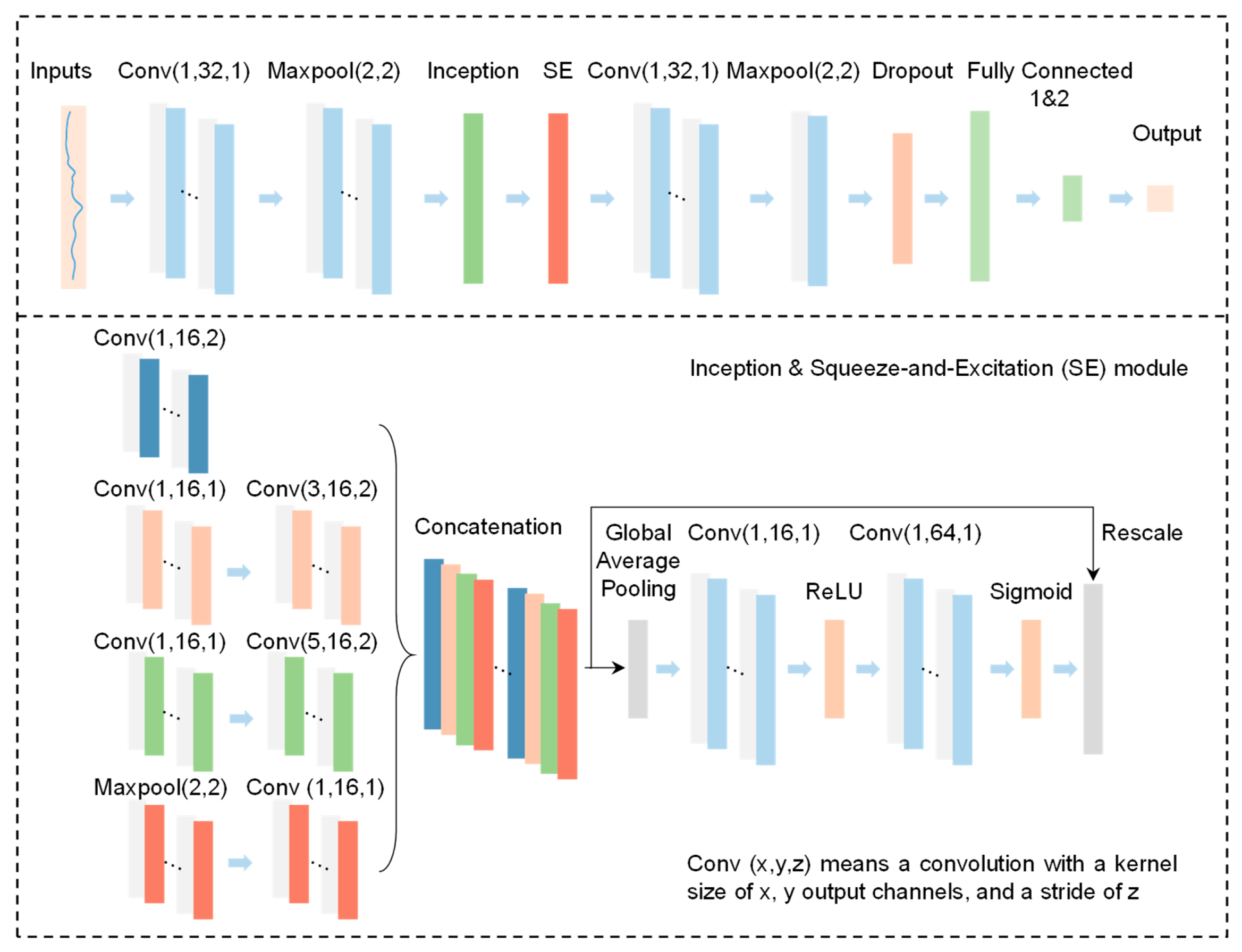

3.3. Multi-Cultivar ISNet-1D for Peach Firmness Prediction

To further enhance prediction accuracy, a 1D-CNN architecture incorporating an Inception module and a squeeze-and-excitation attention mechanism (ISNet-1D) was specifically designed to process raw PSDs. This hierarchical structure enabled the model to automatically learn and integrate features directly from the signal, spanning broad resonance patterns to fine-grained textural components. The proposed ISNet-1D demonstrated significantly improved performance compared to conventional machine learning approaches. On the test set, the ISNet-1D achieved significant improvements over the SVR model, with an 18.19% higher

(0.8069), an 18.36% lower RMSEP (0.9206 N/mm), and a 25.98% higher

(2.2879). Notably, an RPDP value exceeding 2.0 suggested good predictive capability and robustness for practical applications.

The gradient-weighted class activation mapping (Grad-CAM) method was applied to enhance the interpretability of the ISNet-1D [

31]. It was used to generate visual heatmaps by weighting and upsampling the feature maps from the final convolutional layer. As shown in

Figure 9, the relative importance of different regions in a typical PSD was represented by a color gradient from blue to red, with red indicating higher relevance. The results demonstrated that areas adjacent to the first two resonant frequencies were particularly important for predicting firmness, consistent with the physical principle that resonant frequency correlated with material stiffness. However, comparisons across three peach cultivars revealed that the relationship between resonant frequencies and firmness was neither strictly linear nor uniformly positive. Consistent with this, the heatmap suggested that not all resonant frequencies contributed equally to the model’s decisions.

The ISNet-1D also assigned importance to spectral troughs and specific non-resonant frequency bands (e.g., 0–280 Hz and 4600–5120 Hz), which were typically overlooked in conventional parameter-based methods. These findings suggested that the model leveraged complementary information across the entire spectrum to make its decisions, contributing to its superior performance. Unlike PLSR and SVR methods, the ISNet-1D learned discriminative features directly from raw acoustic vibration spectra. By integrating multi-scale convolutional filters with a channel-wise attention mechanism, the network adaptively prioritized both global resonant patterns and localized high-frequency components that were closely related to peach firmness. This end-to-end learning framework reduced potential information loss associated with manual feature engineering and captured complex, nonlinear relationships in the PSDs more effectively.

3.4. Exploration of Model Generalizability via Transfer Learning

To evaluate the generalizability of the original model, which was trained on data from three cultivars over a single growing season, an external validation was conducted using an independent set of 120 fruit samples of the ‘Baifeng’ peach cultivar. These samples were collected in July 2025 from an orchard in Wuxi, Jiangsu Province, following the same experimental procedures described in the

Section 2. The firmness values for the external dataset ranged from 0.45 to 4.47 N/mm, with a mean of 1.79 N/mm and a standard deviation of 1.07 N/mm (

Table 3). The initial predictions generated by the original ISNet-1D for this previously unseen cultivar exhibited limited accuracy, indicating cultivar-specific dependency and poor cross-cultivar transferability.

A hierarchical transfer learning strategy was implemented to update the model. After loading the pretrained ISNet-1D, the weights of all deep convolutional layers were frozen to preserve generic vibrational features learned from the original dataset. The last convolutional layer was made trainable with a reduced learning rate, allowing for adjustments to higher-level abstract features relevant to the new cultivar. Meanwhile, the two fully connected layers at the network’s output were set as fully trainable under standard learning rates to recalibrate the feature combination weights for better accommodation of inter-cultivar variability. The new dataset was split into training and validation subsets at a 4:1 ratio. Subsequently, the model was fine-tuned in an end-to-end manner via transfer learning and independently validated. After transfer learning, a significant improvement in model performance was observed. For the calibration set, the

, RMSEC, and RPDC were 0.7500, 0.5368 N/mm, and 2.2503, respectively. For the validation set, the

, RMSEV, and RPDV were 0.7120, 0.5370 N/mm, and 1.9304, respectively. The results indicated that the hierarchical transfer learning approach significantly mitigated the initial decline in predictive accuracy and improved the model’s adaptability to the new cultivar.

4. Discussion

Current acoustic vibration methods for fruit firmness evaluation predominantly rely on contact-based excitation or vibration measurement techniques and are generally applied to a single fruit cultivar. To achieve rapid and accurate firmness assessment across multiple peach cultivars, this study proposed a noncontact acoustic vibration detection system combining air-jet excitation and an LDV. Deep learning algorithms were used to develop a cross-cultivar model for accurate peach firmness prediction.

In terms of excitation approaches, sinusoidal sweep and impact excitation exhibit distinct characteristics. Sinusoidal sweep excitation delivers energy at one frequency at a time, effectively stimulating structural vibrations across all frequency points and aiding in the clear identification of even weak resonance peaks. However, this method is relatively time-consuming and not ideally suited for rapid detection. In contrast, impact excitation is faster and can deliver a broadband excitation. An ideal instantaneous impact exhibits a flat frequency spectrum over a theoretically infinite frequency range, distributing energy uniformly across an extremely broad band. Under practical conditions, impacts have finite duration, and the spectral width is inversely proportional to the pulse duration. Shorter pulses encompass richer high-frequency components, while longer pulses preserve more low-frequency energy but attenuate at higher frequencies. The instantaneous air jet employed in this work produces a very brief pulse. Although the energy per unit frequency is relatively low, experimental results indicated that this technique was capable of acquiring acoustic vibration spectra with clearly identifiable resonant peaks for peaches. Subsequent research may focus on incorporating impact excitation into online inspection systems to improve the intelligence and efficiency of detection.

Analysis of acoustic vibration spectra obtained from multiple peach cultivars indicated that the relationship between resonant frequency and firmness was neither strictly linear nor consistently positive. Therefore, prediction models that rely exclusively on resonant frequency or other conventional spectral parameters may exhibit limited applicability when assessing firmness across different cultivars with divergent physical properties. To enhance prediction accuracy, a one-dimensional convolutional neural network (ISNet-1D) was designed, incorporating a multi-scale Inception module and the squeeze-and-excitation attention mechanism for processing raw PSDs. This end-to-end learning framework adaptively emphasized global resonance patterns and localized high-frequency components that were closely associated with peach firmness. Compared with PLSR and SVR models, ISNet-1D demonstrated good firmness prediction performance for multi-cultivar peaches.

Furthermore, the method proposed in this study is not restricted to peaches and can be extended to other spherical or near-spherical fruits, such as apples and pears. By utilizing the air-jet excitation and LDV-based acoustic vibration measurement approach, acoustic vibration data for specific fruits can be obtained. Adoption of the proposed deep learning architecture could further allow the development of prediction models for estimating firmness or other mechanical quality attributes tailored to specific fruit types. Future efforts should focus on evaluating the adaptability and generalization capacity of the model across a broader range of fruit species, and on optimizing the system for fully automated, high-throughput industrial sorting operations.

5. Conclusions

This study developed a noncontact methodology for the accurate evaluation of peach firmness across multiple cultivars. The approach combined air-jet excitation with the LDV to acquire acoustic vibration signals, along with a dedicated deep learning architecture (ISNet-1D) for firmness prediction. Experimental results showed that transient air-jet impact provided effective broadband excitation, producing high-quality spectral data suitable for rapid inspection. In comparative analyses, the ISNet-1D outperformed conventional machine learning methods. On the test set, ISNet-1D achieved an

of 0.8069, an RMSEP of 0.9206 N/mm, and an RPDP of 2.2879. These values were 18.19%, 18.36%, and 25.98% higher than those of the SVR model, respectively. By incorporating multi-scale feature extraction and channel attention mechanisms, the ISNet-1D autonomously learned discriminative features from raw spectral data, enabling it to effectively capture the complex, nonlinear relationships between vibration characteristics and firmness. In conclusion, the integration of noncontact acoustic vibration detection with deep learning offers a feasible framework for assessing the firmness of specific peach cultivars.

However, the development of a universal and robust model applicable across multiple cultivars and growing seasons remains challenging and typically requires extensive datasets. Traditional chemometric models often exhibit performance degradation when applied to different cultivars or harvest years, frequently necessitating labor-intensive remodeling. The present study demonstrates that a transfer learning-based adaptation strategy potentially addresses this limitation. By leveraging a limited number of target-specific samples, the proposed approach maintains predictive performance while reducing data requirements, offering a practical pathway toward enhancing model generalizability in real-world applications. Future work will focus on extending and optimizing the method to a wider range of fruit types.