Building Technological Legitimacy: The Impact of Communication Strategies on Public Acceptance of Genetically Modified Foods in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework: Technological Legitimacy

2.2. GM Foods Consumption and Consumer Preferences

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Survey Design

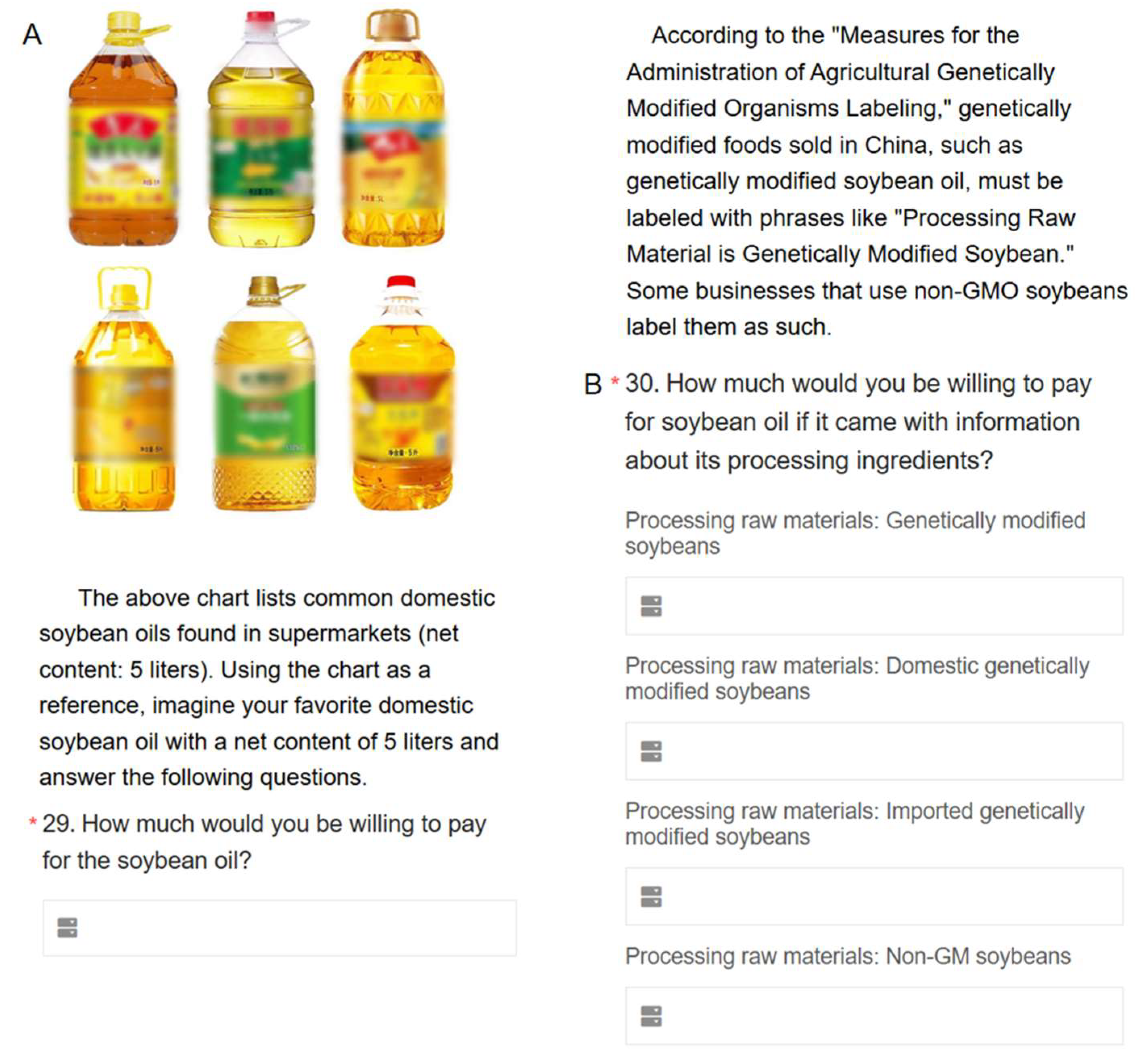

3.2. Contingent Valuation Experiment

3.3. Data and Variable Description

3.4. Econometric Model

4. Results

4.1. Statistics of WTP

4.2. Information Interventions and Determinants of WTP

4.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. Sustainable Food Systems: Concept and Framework; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, K.R.; Fanzo, J.; Haddad, L.; Herrero, M.; Moncayo, J.R.; Herforth, A.; Remans, R.; Guarin, A.; Resnick, D.; Covic, N.; et al. The state of food systems worldwide in the countdown to 2030. Nat. Food 2023, 4, 1090–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul, A.M.; Brini, F.; Rouached, H.; Masmoudi, K. Genetically engineered crops for sustainably enhanced food production systems. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1027828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey-Serres, J.; Parker, J.E.; Ainsworth, E.A.; Oldroyd, G.E.D.; Schroeder, J.I. Genetic strategies for improving crop yields. Nature 2019, 575, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhsh, A.; Sırel, I.A.; Kaya, R.B.; Ataman, I.H.; Tillaboeva, S.; Dönmez, B.A.; Yeşil, B.; Yel, I.; Tekinsoy, M.; Duru, E. In Policy Issues in Genetically Modified Crops; Singh, P., Borthakur, A., Singh, A.A., Kumar, A., Singh, K.K., Eds.; Chapter 6—Contribution of Genetically Modified Crops in Agricultural Production: Success Stories. Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 111–142. ISBN 978-0-12-820780-2. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.; Li, H.; Tang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Liu, T.; Wang, Y. Trends in the global commercialization of genetically modified crops in 2023. J. Integr. Agric. 2024, 23, 3943–3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbashi, S.; Adebo, O.; Adebiyi, J.A.; Targuma, S.; Tebele, S.; Areo, O.M.; Olopade, B.; Odukoya, J.O.; Njobeh, P. Food safety, food security and genetically modified organisms in Africa: A current perspective. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2021, 37, 30–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Raza, G.; Waheed, T.; Mukhtar, Z. In Policy Issues in Genetically Modified Crops; Singh, P., Borthakur, A., Singh, A.A., Kumar, A., Singh, K.K., Eds.; Chapter 16—Food Safety Issues and Challenges of GM Crops. Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 355–369. ISBN 978-0-12-820780-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bawa, A.S.; Anilakumar, K.R. Genetically modified foods: Safety, risks and public concerns—A review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 50, 1035–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chon, M.G.; Xu, L.; Liu, J.; Kim, J.N.; Kim, J. From Mind to Mouth: Understanding Active Publics in China and Their Communicative Behaviors on GM Foods. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, M.L.P.; Blessing, J.N.; Myrick, J.G. Two-sided messages in GM food news: The role of argument order and deference toward scientific authority. J. Risk Res. 2025, 28, 945–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumba, L.E. Food aid Crisis and Communication About GM Foods: Experiences from Southern Africa; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2007; pp. 338–364. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Fang, S. Decisions to choose genetically modified foods: How do people’s perceptions of science and scientists affect their choices? J. Sci. Commun. 2020, 19, A01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Wang, G. Understanding the Factors Driving Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Gene-Edited Foods in China. Foods 2024, 13, 2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, B.; Kolady, D.; Just, D.; Ishaq, M. Effect of information and innovator reputation on consumers’ willingness to pay for genome-edited foods. Food. Qual. Prefer. 2023, 107, 104825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Network, R.N. (Trade Information Issue 41 of 2025) Foreign Press: China Imported Zero US Soybeans in September. 2025. Available online: https://www.ccpitjx.org.cn/ccpitjx/col/col47303/content/content_1981184828050444288.html (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- China News Weekly. Limited Approval: China’s Genetically Modified Food Crops Officially Enter Commercialization. China News Weekly, 2024 February 1. [Google Scholar]

- World Agroforestry Network. Policy Expansion and Acceleration, with Various Markets Competing Fiercely: China’s Genetically Modified Technology Industry Has Entered a Fast-Track Development Phase. Available online: https://cn.agropages.com/News/printnew-35872.htm (accessed on 25 September 2025). (In Chinese).

- Xiao, Z.; Kerr, W.A. The political economy of China’s GMO commercialization dilemma. Food Energy Secur. 2022, 11, e409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankesteijn, M.; Bossink, B. Assessing the Legitimacy of Technological Innovation in the Public Sphere: Recovering Raw Materials from Waste Water. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy—Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, R.W. Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests & Identities; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jansma, S.R.; Gosselt, J.F.; Kuipers, K.; de Jong, M.D.T. Technology legitimation in the public discourse: Applying the pillars of legitimacy on GM food. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2020, 32, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Li, Y.; Li, X. Increasing Vegetable Oil Demand in China: Impacts on the International Soybean Market. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. 2021, 23, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiong, H.; Zhang, J. Determinants of China’s Soybean Import Trade. Public Organ. Rev. 2025, 25, 1683–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. China Expands GMO Cultivation for Food Security, Approving New Varieties of Soybeans and Corns. Available online: https://www.foodingredientsfirst.com/news/china-expands-gmo-cultivation-for-food-security-approving-new-varieties-of-soybeans-and-corns.html (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Gao, Z.; Yu, X.; Li, C.; McFadden, B.R. The interaction between country of origin and genetically modified orange juice in urban China. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 71, 475–484. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, M.A.; Zeitz, G.J. Beyond survival: Achieving new venture growth by building legitimacy. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2002, 27, 414–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, R.; Oliver, C.; Suddaby, R.; Sahlin-Andersson, K. The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Institutionalism; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; ISBN 9781412931236/1412931231. [Google Scholar]

- Aldrich, H.E.; Fiol, C.M. Fools rush in—The institutional context of industry creation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1994, 19, 645–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruef, M.; Scott, W.R. A multidimensional model of organizational legitimacy: Hospital survival in changing institutional environments. Adm. Sci. Q. 1998, 43, 877–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, A. The precautionary principle and genetically modified organisms: A bone of contention between European institutions and member states. J. Law Biosci. 2021, 8, lsab12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. How GMOs Are Regulated in the United States. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/agricultural-biotechnology/how-gmos-are-regulated-united-states (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Babar, U.; Xu, R. In GMOs and Political Stance; Nawaz, M.A., Chung, G., Golokhvast, K.S., Tsatsakis, A.M., Eds.; Chapter 4—Agricultural genetically modified organisms (GMOs) regulation in China. Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 53–74. ISBN 978-0-12-823903-2. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F. Research on improving self-sufficiency rate of soybean oil in China in the new period from the perspective of oil processing. Chin. Acad. Agric. Sci. 2023, 45, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F.; Geng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, C.; Chen, Y.; Sun, L.; Xie, W.; Ali, T.; Fujita, T. Assessing sustainability of soybean supply in China: Evidence from provincial production and trade data. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 119006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Popp, M.P.; Wolfe, E.J.; Nayga, R.M.; Popp, J.S.; Chen, P.; Seo, H. Information and order of information effects on consumers’ acceptance and valuation for genetically modified edamame soybean. PLoS ONE. 2018, 13, e0206300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steur, H.D.; Buysse, J.; Feng, S.; Gellynck, X. Role of Information on Consumers’ Willingness-to-pay for Genetically-modified Rice with Health Benefits: An Application to China. Asian Econ. J. 2013, 27, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, J.L.; House, L.O.; Valli, C.; Jaeger, S.R.; Moore, M.; Morrow, J.L.; Traill, W.B. Effect of information about benefits of biotechnology on consumer acceptance of genetically modified food: Evidence from experimental auctions in the United States, England, and France. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2004, 31, 179–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorne, F.; Fox, J.A.S.; Mullins, E.; Wallace, M. Consumer Willingness-to-Pay for Genetically Modified Potatoes in Ireland: An Experimental Auction Approach. Agribusiness 2017, 33, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, M.; Chaves, C. Perceptions and valuation of GM food: A study on the impact and importance of information provision. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 4110–4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Zhong, F.; Ding, Y. Actual media reports on GM foods and Chinese consumers’ willingness to pay for GM soybean oil. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2006, 31, 376–390. [Google Scholar]

- Kajale, D.B.; Becker, T.C. Effects of Information on Young Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Genetically Modified Food: Experimental Auction Analysis. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2014, 53, 292–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinawy, R.N. Unraveling consumer behavior: Exploring the influence of consumer ethnocentrism, domestic country bias, brand trust, and purchasing intentions. Strateg. Change 2025, 34, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Koushik, K.; Kishor, N. The state of country-of-origin research: A bibliometric review of trends and future. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2025, 30, 100337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlegh, P.W.J.; Steenkamp, J.E.M. A review and meta-analysis of country-of-origin research. J. Econ. Psychol. 1999, 20, 521–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Kim, W.B.; Lee, S.H.; Baek, E.; Yan, X.; Yeon, J.; Yoo, Y.; Kang, S. Relations among consumer boycotts, country affinity, and global brands: The moderating effect of subjective norms. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2025, 30, 100335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montresor, S. Techno-globalism, techno-nationalism and technological systems: Organizing the evidence. Technovation 2001, 21, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. The Experts in Genetic Modification are Concerned About: Public Awareness and Education Campaigns. Available online: https://www.moa.gov.cn/ztzl/zjyqwgz/kpxc/ (accessed on 1 October 2025). (In Chinese)

- Xin, Y.; Sheng, J.; Yi, F.; Hu, Y. How Sugar Labeling Affects Consumer Sugar Reduction: A Case of Sucrose Grade Labels in China. Foods 2024, 13, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.; Park, J.; Jeong, S.W. Let me shop alone: Consumers’ psychological reactance toward retail robotics. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 212, 123962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughner, R.S.; Dumitrescu, C. The effectiveness of sugar-sweetened beverage warning labels: An examination of consumer reactance and cost of compliance. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 182, 114812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.D.; Largey, A.; McMullan, C. The impact of gender on risk perception: Implications for EU member states’ national risk assessment processes. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 63, 102452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, C. Gender differences in optimism, loss aversion and attitudes towards risk. Br. J. Psychol. 2023, 114, 928–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driessen, C.; Bennett, R.; Cameron, A.J.; Kelly, B.; Bhatti, A.; Backholer, K. Understanding parents’ perceptions of children’s exposure to unhealthy food marketing in digital and retail environments. Appetite 2024, 200, 107553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez, A.L.; Alcaire, F.; Vidal, L.; Varela, P.; Næs, T.; Ares, G. The influence of label information on the snacks parents choose for their children: Individual differences in a choice based conjoint test. Food. Qual. Prefer. 2021, 94, 104296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, W.J. The Knowledge Deficit Model and Science Communication; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, V.M. In Values, Pluralism, and Pragmatism: Themes from the Work of Matthew J. Brown; Tsou, J.Y., Shaw, J., Fehr, C., Eds.; Dismantling the Deficit Model of Science Communication Using Ludwik Fleck’s Theory of Thinking Collectives. Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 117–137. ISBN 978-3-031-92958-8. [Google Scholar]

| Information Group | Message |

|---|---|

| Purpose strategy | Soybeans are an important raw material for edible oils, soy products, and animal feed in our country, and the demand for them has grown rapidly in recent years. However, due to the low yield of conventional soybeans and the limited amount of arable land per capita, it is difficult for China to achieve self-sufficiency in soybean production. To rely solely on conventional soybeans for self-sufficiency, China would need to increase its soybean area by an additional 800 million mu, which is equivalent to dedicating 45% of its current arable land to soybean cultivation. As a result, we have long relied on soybean imports to meet our needs, importing 91.08 million tons in 2022 from countries such as Brazil and the United States, mostly GM soybeans. This has led to external soybean dependence of more than 80%, making us vulnerable to other countries in terms of food security. Given the complex and volatile international situation, there is an urgent need to accelerate the industrialization of GM soybean breeding. Using independently developed GM technology to increase soybean self-sufficiency, we can ensure food security. |

| Maturity strategy | GM technology is an important means to enhance the competitiveness of soybean industry in China. After more than 20 years of scientific and technological innovation, breeding techniques for herbicide tolerance and insect resistance in GM soybeans have matured. GM varieties that have been approved for pilot testing now have independent intellectual property rights in China, and the industrialized cultivation of these products can significantly reduce production costs and increase soybean yields. Taking herbicide-resistant transgenic soybeans as an example, as of June 2023, five herbicide-resistant soybean varieties bred using transgenic technology had received safety certificates for production and use. These varieties can reduce weed control costs by more than 30 RMB per mu, increase yields by over 10% compared to main crop varieties, and improve efficiency by an average of 100 RMB per mu while enabling reasonable crop rotation. Our proprietary herbicide-tolerant soybean has also been approved for commercial cultivation in Argentina, completing the international rollout of transgenic products. |

| Safety strategy | In China, all GM crops go through a series of rigorous safety evaluations and approvals before being released to the market. The process is based on internationally accepted practices, as well as national laws, regulations, and standard specifications. The process is divided into five stages, including experimental research, intermediate testing, environmental release, production testing and application for safety certificates. It includes the safety evaluation of both food safety risks and environmental safety risks. If any problems that may affect health or environmental safety are found at any stage, the R&D testing stops immediately and does not proceed to the industrialization stage. For example, the domestic GM soybean, Zhonghuang 6106, received a safety certificate for production and use. This certification followed an extensive, 11-year evaluation by the National Committee on the Safety of Genetically Modified Organisms in Agriculture. The committee systematically assessed the soybean’s safety for human consumption and its impact on the environment. |

| Variable | Description | Percentage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Control | Treatment1 | Treatment2 | Treatment3 | ||

| Gender | Female | 56.37 | 60.34 | 52.15 | 54.73 | 58.33 |

| Male | 43.63 | 39.66 | 47.85 | 45.27 | 41.67 | |

| Age | 18–25 | 14.99 | 13.90 | 14.52 | 15.54 | 16.00 |

| 26–30 | 29.31 | 27.80 | 31.68 | 31.42 | 26.33 | |

| 31–40 | 42.97 | 43.73 | 43.23 | 40.20 | 44.67 | |

| 41–50 | 9.46 | 11.53 | 6.60 | 9.12 | 10.67 | |

| 51–60 | 3.10 | 2.71 | 3.96 | 3.38 | 2.33 | |

| Above 60 | 0.17 | 0.34 | 0.00 | 0.34 | 0.00 | |

| Education | High school and below | 4.69 | 3.39 | 4.62 | 6.42 | 4.33 |

| Some college and Bachelor’s degree | 85.18 | 89.83 | 82.18 | 83.45 | 85.33 | |

| Master’s degree or equivalent | 10.13 | 6.78 | 13.20 | 10.14 | 10.33 | |

| Monthly Income | Under 4999 yuan | 4.77 | 4.75 | 5.28 | 5.74 | 3.33 |

| 5000–9999 yuan | 20.69 | 18.31 | 21.45 | 20.95 | 22.00 | |

| 10,000–14,999 yuan | 25.96 | 29.15 | 24.75 | 24.66 | 25.33 | |

| 15,000–19,999 yuan | 23.79 | 19.32 | 28.05 | 22.97 | 24.67 | |

| 20,000 yuan and above | 24.79 | 28.47 | 20.46 | 25.68 | 24.67 | |

| Knowledge | Mean value | 3.77 | 3.69 | 3.91 | 3.73 | 3.74 |

| GM | Domestic GM | Imported GM | Non-GMO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No information | 45.482 | 46.564 | 46.426 | 62.328 |

| (1.391) | (1.398) | (1.441) | (1.428) | |

| Purpose strategy | 45.881 | 49.872 | 46.747 | 62.139 |

| (1.372) | (1.379) | (1.422) | (1.409) | |

| Maturity strategy | 47.753 | 49.039 | 47.994 | 61.867 |

| (1.382) | (1.389) | (1.433) | (1.419) | |

| Safety strategy | 39.882 | 41.511 | 41.221 | 58.316 |

| (1.378) | (1.385) | (1.428) | (1.415) |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | GM | Domestic GM | Imported GM | Non-GMO |

| Purpose strategy | 0.399 | 3.308 * | 0.321 | −0.189 |

| (1.965) | (1.976) | (2.037) | (2.018) | |

| Maturity strategy | 2.271 | 2.476 | 1.568 | −0.461 |

| (1.961) | (1.971) | (2.033) | (2.014) | |

| Safety strategy | −5.600 *** | −5.053 ** | −5.205 ** | −4.012 ** |

| (1.962) | (1.972) | (2.034) | (2.015) | |

| Gender | −1.527 | −1.932 | −2.941 ** | −2.046 |

| (1.410) | (1.417) | (1.461) | (1.448) | |

| Age | −0.288 *** | −0.348 *** | −0.326 *** | −0.044 |

| (0.107) | (0.107) | (0.111) | (0.110) | |

| Based on government agencies | ||||

| Public Institution | −11.502 ** | −8.878 | −7.062 | −6.017 |

| (5.416) | (5.444) | (5.613) | (5.561) | |

| Enterprise | −12.018 ** | −9.513 * | −7.334 | −5.665 |

| (5.144) | (5.171) | (5.331) | (5.282) | |

| Student | −13.710 ** | −9.330 | −9.642 | −8.324 |

| (5.959) | (5.990) | (6.176) | (6.119) | |

| Agricultural producers | −20.641 ** | −19.338 ** | −12.875 | −11.671 |

| (8.590) | (8.634) | (8.902) | (8.820) | |

| Others | −9.950 * | −6.127 | −5.162 | −7.815 |

| (5.899) | (5.930) | (6.114) | (6.057) | |

| Based on the level of high school education or below | ||||

| University or junior college | 2.321 | 1.203 | 2.969 | 6.063 * |

| (3.413) | (3.430) | (3.537) | (3.504) | |

| Master’s degree or above | 2.917 | 3.334 | 4.476 | 9.104 ** |

| (4.031) | (4.052) | (4.178) | (4.139) | |

| Based on the low-income group | ||||

| Middle and low income | 2.687 | 1.989 | 4.057 | 6.612 * |

| (3.578) | (3.597) | (3.708) | (3.674) | |

| Middle income | 4.150 | 2.684 | 4.798 | 6.833 * |

| (3.589) | (3.608) | (3.720) | (3.685) | |

| Middle and high income levels | 3.721 | 2.387 | 3.895 | 9.094 ** |

| (3.655) | (3.673) | (3.788) | (3.752) | |

| High income | 4.268 | 2.337 | 4.449 | 11.691 *** |

| (3.674) | (3.693) | (3.807) | (3.772) | |

| people aged 60 and above | −0.754 | 0.276 | −0.001 | −1.123 |

| (1.411) | (1.418) | (1.463) | (1.449) | |

| children under the age of 18 | 2.840 * | 3.644 ** | 3.322 * | 3.741 ** |

| (1.664) | (1.672) | (1.724) | (1.708) | |

| Biotechnology knowledge | 1.256 ** | 0.677 | 0.299 | 0.908 |

| (0.592) | (0.595) | (0.614) | (0.608) | |

| Perception of GM Food Safety | 8.651 *** | 9.336 *** | 9.946 *** | −0.350 |

| (0.785) | (0.789) | (0.813) | (0.806) | |

| Pay attention to the price of soybean oil | 5.126 *** | 6.702 *** | 7.009 *** | 5.031 *** |

| (1.848) | (1.858) | (1.915) | (1.898) | |

| Intercept term | 23.476 *** | 23.790 *** | 17.671 * | 47.852 *** |

| (8.874) | (8.919) | (9.196) | (9.111) | |

| Sample size | 1194 | 1194 | 1194 | 1194 |

| GM | Domestic GM | Imported GM | Non-GMO | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Purpose strategy | ||||

| Female | 0.476 | 3.288 | −0.169 | −0.010 | |

| Male | 1.779 | 5.046 * | 2.100 | 1.088 | |

| Maturity strategy | |||||

| Female | −0.112 | −0.238 | −0.639 | −2.596 | |

| Male | 4.729 | 5.614 * | 3.626 | 2.306 | |

| Safety strategy | |||||

| Female | −9.553 *** | −8.845 *** | −8.826 *** | −6.206 ** | |

| Male | −1.072 | −0.434 | −0.804 | −0.628 | |

| Child | Purpose strategy | ||||

| With child | 0.501 | 4.094 * | 0.469 | −0.197 | |

| Without child | 0.739 | 1.480 | 0.330 | 0.838 | |

| Maturity strategy | |||||

| With child | 1.113 | 2.055 | 0.397 | −1.578 | |

| Without child | 6.213 | 4.501 | 5.331 | 3.766 | |

| Safety strategy | |||||

| With child | −6.049 *** | −4.441 * | −5.744 * | −3.638 | |

| Without child | −4.352 | −6.765 * | −4.261 | −4.351 | |

| Biotechnology knowledge | Purpose strategy | ||||

| High knowledge | 0.362 | 3.904 | 1.063 | 0.844 | |

| Low knowledge | 1.276 | 2.917 | −0.196 | −0.898 | |

| Maturity strategy | |||||

| High knowledge | 4.169 * | 4.559 * | 3.548 | 1.747 | |

| Low knowledge | 0.079 | 0.326 | −0.540 | −2.022 | |

| Safety strategy | |||||

| High knowledge | −3.471 | −2.662 | −2.872 | −2.211 | |

| Low knowledge | −7.718 ** | −7.475 ** | −7.675 ** | −5.292 | |

| Perception of the safety of GM technology | Purpose strategy | ||||

| High awareness | −0.406 | 0.403 | −1.927 | −1.568 | |

| Low awareness | 2.102 | 4.766 *** | 1.281 | 2.041 | |

| Maturity strategy | |||||

| High awareness | 3.046 | −2.152 * | −1.143 | −3.322 | |

| Low awareness | 2.688 | 2.206 ** | 0.0144 | −0.909 | |

| Safety strategy | |||||

| High awareness | −7.504 ** | −2.029 * | −1.791 | 1.134 | |

| Low awareness | −4.115 | 1.652 * | 1.226 | −2.084 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xin, Y.; Sheng, J. Building Technological Legitimacy: The Impact of Communication Strategies on Public Acceptance of Genetically Modified Foods in China. Foods 2025, 14, 3827. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223827

Xin Y, Sheng J. Building Technological Legitimacy: The Impact of Communication Strategies on Public Acceptance of Genetically Modified Foods in China. Foods. 2025; 14(22):3827. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223827

Chicago/Turabian StyleXin, Yijing, and Jiping Sheng. 2025. "Building Technological Legitimacy: The Impact of Communication Strategies on Public Acceptance of Genetically Modified Foods in China" Foods 14, no. 22: 3827. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223827

APA StyleXin, Y., & Sheng, J. (2025). Building Technological Legitimacy: The Impact of Communication Strategies on Public Acceptance of Genetically Modified Foods in China. Foods, 14(22), 3827. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14223827