Zinc Chelates from Low-Molecular-Weight Donkey-Hide Gelatin Peptides: Preparation, Characterization, and Evaluation of In Vitro Antioxidant Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Optimization of the Preparation Process of LMW DHGP–Zinc Chelates

2.2.1. Preparation of LMW DHGP–Zinc Chelates

2.2.2. Single-Factor Experimental Design

2.2.3. Orthogonal Optimization Experimental Design

2.2.4. Determination of the Chelation Rate of Peptide–Zinc

2.3. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.4. Ultraviolet Spectrum (UV)

2.5. Fluorescence Spectra (FL)

2.6. Zeta Potential and Particle Size Analysis

2.7. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.8. Circular Dichroism (CD)

2.9. Analysis of Amino Acid Composition and Content

2.10. Determination of DPPH Free Radical Scavenging Rate

- A0—Absorbance of the blank group;

- A1—Absorbance of the sample group.

2.11. Determination of ABTS Free Radical Scavenging Rate

- A0—Absorbance of the blank group;

- A1—Absorbance of the sample group.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Single-Factor Experimental Results

3.1.1. The Influence of Zinc Source Concentration on the Chelation Rate of Peptide–Zinc

3.1.2. The Influence of the Mass Ratio of Peptide–Zinc on the Chelation Rate of Peptide–Zinc

3.1.3. The Influence of Chelating pH on the Chelation Rate of Peptide–Zinc

3.1.4. The Influence of Chelation Time on the Chelation Rate of Peptide–Zinc

3.1.5. The Influence of Chelation Temperature on the Chelation Rate of Peptide–Zinc

3.2. The Results of Orthogonal Optimization Experimental Design

3.3. SEM Analysis

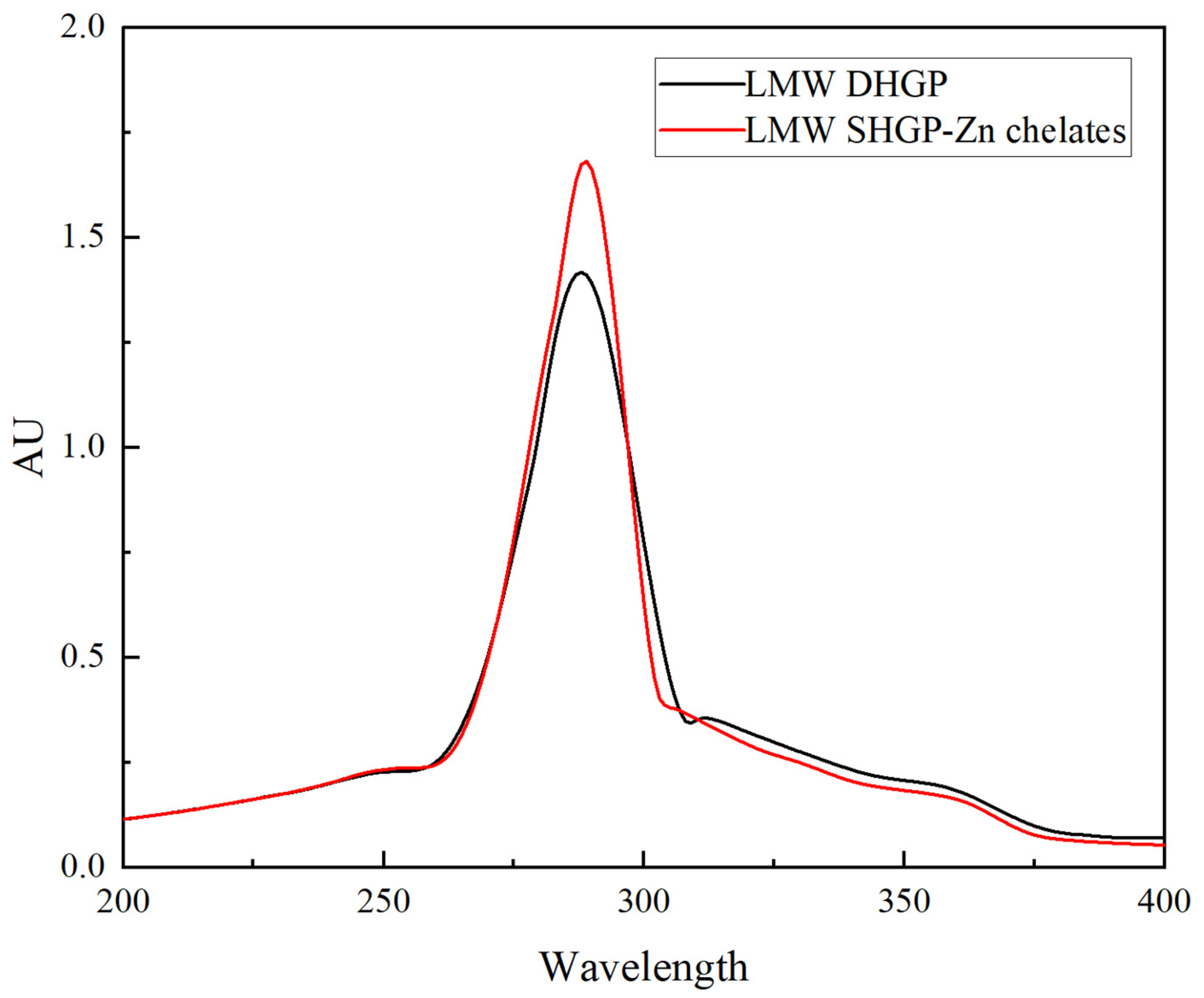

3.4. UV Analysis

3.5. FL Analysis

3.6. Zeta Potential and Particle Size Distribution

3.7. FTIR Analysis

3.8. CD Analysis

3.9. Amino Acid Analysis

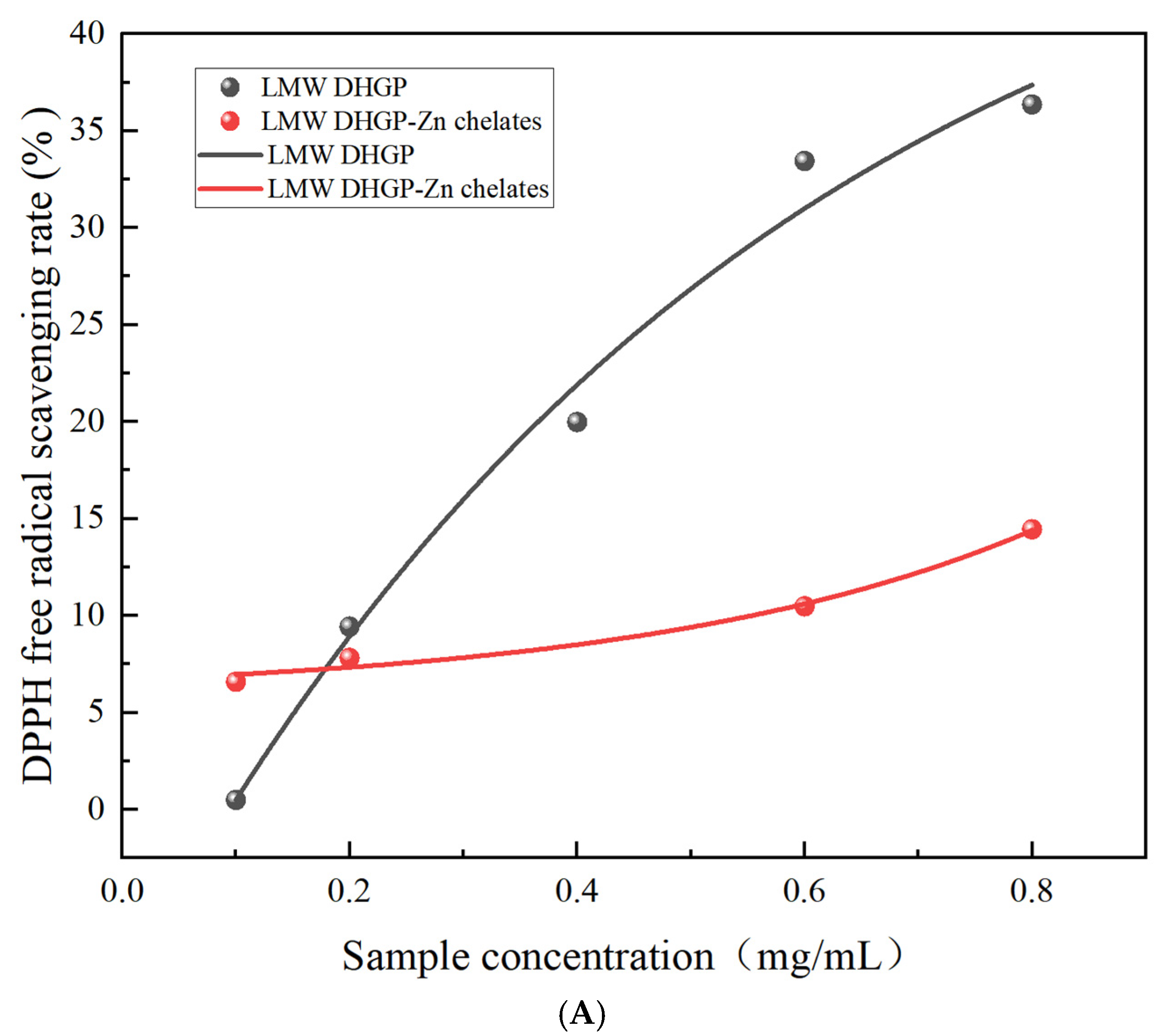

3.10. Analysis of In Vitro Antioxidant Activity

3.10.1. Determination of the Free Radical Scavenging Ability of DPPH

3.10.2. Determination of ABTS Free Radical Scavenging Ability

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LMW | Low molecular weight |

| DHGP | Donkey-hide gelatin peptide |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| CD | Circular dichroism |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared |

| UV | UV-Vis spectroscopy |

| DPPH | 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| ABTS | 2,2-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt |

References

- Yu, X.-J.; Kong, L.-M.; Wang, B.; Zhai, C.-Q.; Lao, Y.-Z.; Zhang, L.-J.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, B.-N. Asini Corii Colla (Ejiao) as a health-care food and traditional Chinese medicine: A review of its chemical composition, pharmacological activity, quality control, modern applications. J. Funct. Foods 2025, 125, 106678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Chen, H.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Qian, J.; Wang, Y.; Qu, H. Identification of bioactive ingredients with immuno-enhancement and anti-oxidative effects from Fufang-Ejiao-Syrup by LC–MS n combined with bioassays. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2016, 117, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhou, F.; Liu, X.; Zhao, M. Particulate nanocomposite from oyster (Crassostrea rivularis) hydrolysates via zinc chelation improves zinc solubility and peptide activity. Food Chem. 2018, 258, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wani, A.L.; Parveen, N.; Ansari, M.O.; Ahmad, M.F.; Jameel, S.; Shadab, G.G.H.A. Zinc: An element of extensive medical importance. Curr. Med. Res. Pract. 2017, 7, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajo, H.; Sabine, E.; Jakob, L.; Monika, N.-B.; Margrit, R. Revised D-A-CH-reference values for the intake of zinc. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2020, 61, 126536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandstead, H.H.; Freeland-Graves, J.H. Dietary phytate, zinc and hidden zinc deficiency. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2014, 28, 414–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Liu, X.; Yu, Y.; Miao, J.; Leng, K.; Gao, H. Preparation process optimization, structural characterization and in vitro digestion stability analysis of Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba) peptides-zinc chelate. Food Chem. 2021, 340, 128056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minghui, Z.; Kunlun, L. Calcium supplements and structure–activity relationship of peptide-calcium chelates: A review. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 31, 1111–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Wang, X.; Zheng, Y.; Shi, P.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Long, N. Millet bran globulin hydrolysate derived tetrapeptide-ferrous chelate: Preparation, structural characterization, security prediction in silico, and stability against different food processing conditions. LWT 2022, 165, 113673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Guan, W.; Guo, Y.; Cui, G.; Du, M.; Wen, Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, B. Preparation, In vitro evaluation of calcium transport, and chelation mechanism of rice bran peptide-calcium chelate. Food Biosci. 2025, 71, 107030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ding, X.; Li, M. Preparation, characterization and in vitro stability of iron-chelating peptides from mung beans. Food Chem. 2021, 349, 129101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.; Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Ni, Y.; Liu, M.; Xu, S. Preparation, characterization, assembly, and stability of walnut peptide-zinc complexes and its ability to promote zinc transport in Caco-2 cells. Food Chem. X 2025, 31, 103046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.; Wang, S.; Zhu, X.; Li, Q.; Fan, Y.; Cheng, D.; Li, B. A novel calcium-binding peptide from Antarctic krill protein hydrolysates and identification of binding sites of calcium-peptide complex. Food Chem. 2018, 243, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Sun, J.; Jiao, Y.; Yang, M.; Dong, M.; Hu, W. Preparation, structural characterization, and performance evaluation of antler plate collagen peptide-calcium chelates. J. Funct. Foods 2025, 131, 106953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, A.; Mu, B.; Li, K.; Deng, Q.; Wang, J.; Piao, C.; Li, T.; Cui, M.; Li, G.; Li, H. Preparation, characterization, and antioxidant activity of bovine bone peptide-calcium chelate against oxidative stress-induced injury in Caco-2 cells. Bioorg. Chem. 2025, 165, 108958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; He, L.; Liang, Y.; Yue, L.; Peng, W.; Jin, G.; Ma, M. Preparation process optimization of pig bone collagen peptide-calcium chelate using response surface methodology and its structural characterization and stability analysis. Food Chem. 2019, 284, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Ni, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Du, B.; Luo, H.; Lin, D. Production of novel mung bean peptides-based zinc supplement: Process optimization, chelation mechanism, and stability assessment in vitro. Food Biosci. 2024, 59, 104188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Gao, X.; Leng, Y.; Xia, B.; Bu, G.; Yang, C.; Zhu, T.; Chen, F. Separation, identification and chelation mechanism of novel zinc-chelating peptides from soybean protein enzymatic hydrolysate. LWT 2025, 233, 118518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yajun, Z.; Min, G.; Chaoxia, C.; Junru, L.; Yuanjing, L.; Zhixuan, H.; Ying, A. Structural and physicochemical characteristics, stability, toxicity and antioxidant activity of peptide-zinc chelate from coconut cake globulin hydrolysates. LWT 2023, 173, 114367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Guanhao, B.; Fusheng, C.; Tanghao, L. Preparation and structural characterization of peanut peptide–zinc chelate. CyTA-J. Food 2020, 18, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.; Xu, L.; Fan, C.; Cao, L.; Guo, X. Structural Characteristics and Antioxidant Mechanism of Donkey-Hide Gelatin Peptides by Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Molecules 2023, 28, 7975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Du, B.; Song, Z.; Deng, G.; Shi, Y.; Li, T.; Huang, Y. Antioxidant activity analysis of collagen peptide-magnesium chelate. Polym. Test. 2023, 117, 107822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Jiang, H.; Dai, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, M.; Sheng, J.; Tian, Y.; Tao, L. Glycated walnut peptide-calcium chelates: Structural properties, calcium absorption enhancement mechanism, and osteogenic effects. Food Chem. 2025, 489, 145039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, F.; Fu, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhu, H.; Yu, Y.; Feng, X.; Sun, Y.; Dai, H.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z.; et al. Calcium-chelating peptides from rabbit bone collagen: Characterization, identification and mechanism elucidation. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2024, 13, 1485–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Liu, Y.; Yang, T.; Tian, Q.; Zhao, X.; Hou, H. Discovery of novel calcium-chelating peptides from Antarctic krill: Structural elucidation and dynamic coordination mechanisms. Food Chem. 2025, 493, 145809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Z.; Mu, G.; Qian, F. Novel insights into whey protein peptide-iron chelating agents: Structural characterization, in vitro stability and functional properties. Food Biosci. 2024, 60, 104317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, W.; Shan, X.; Xiangyu, C.; Jihui, W. Structural characterisation, gastrointestinal digestion stability and transepithelial transport study of casein peptide–zinc chelate. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 2770–2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, L.; Cai, C.; Bandara, N.; Li, P.; Wu, K.; Hong, H.; Chen, L. Preparation and characterization of Sipunculus nudus peptide-calcium chelate: Structural insights and osteogenic bioactivity assessment. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 122, 106497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Liang, L.; Kang, Y.; Yu, R.; Wang, J.; Fan, D. Preparation, characterization, and property evaluation of Hericium erinaceus peptide–calcium chelate. Front. Nutr. 2024, 10, 1337407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, L.; XiuYun, M.; XinXin, S.; WenFeng, L. Preparation, characterization, and properties of wampee seed antioxidant peptides-iron chelate. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, e16513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Wang, L.; Liang, J.; Jin, F.; Wang, F. Preparation, characterization and microencapsulation of walnut (Juglans regia L.) peptides-zinc chelate. J. Food Sci. 2024, 89, 5618–5632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, W.; Gao, X.; Tang, L. Preparation and Cellular Absorption of Zinc-chelating Peptides Derived from Sika Deer Blood. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2023, 11, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongru, Z.; Laiyu, Z.; Qingshan, S.; Liwei, Q.; Shan, J.; Yujie, G.; Chunhui, Z.; Aurore, R. Preparation of cattle bone collagen peptides-calcium chelate and its structural characterization and stability. LWT 2021, 144, 111264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinhong, W.; Tang, M.; Xixi, C.; Shaoyun, W. Novel Calcium-Chelating Peptides from Octopus Scraps and their Corresponding Calcium Bioavailability. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 99, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Gao, A.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Chen, Y. Preparation of cucumber seed peptide-calcium chelate by liquid state fermentation and its characterization. Food Chem. 2017, 229, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Ning, C.; Wang, M.; Wei, M.; Ren, Y.; Li, W. Structural, antioxidant activity, and stability studies of jellyfish collagen peptide–calcium chelates. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Luo, X.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, Z. Isolation of a novel calcium-binding peptide from wheat germ protein hydrolysates and the prediction for its mechanism of combination. Food Chem. 2018, 239, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadou, I.; Le, G.-W.; Shi, Y.-H.; Jin, S. Reducing, Radical Scavenging, and Chelation Properties of Fermented Soy Protein Meal Hydrolysate by Lactobacillus plantarum LP6. Int. J. Food Prop. 2011, 14, 654–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Lin, L.; Su, G.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, M. Pitfalls of using 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay to assess the radical scavenging activity of peptides: Its susceptibility to interference and low reactivity towards peptides. Food Res. Int. 2015, 76, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenjuan, Q.; Yiting, F.; Ting, X.; Yuhan, L.; Hafida, W.; Haile, M. Preparation of corn ACE inhibitory peptide-ferrous chelate by dual-frequency ultrasound and its structure and stability analyses. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2022, 83, 105937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congmiao, L.; Yue, Z.; Leipeng, C.; Yuhuan, L.; Zhenghua, H.; Bin, L.; Lingxia, X. Characterization and stability of soybean meal peptide-zinc chelate prepared by solid state fermentation with Aspergillus oryzae. Food Biosci. 2023, 56, 103380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Liu, T.; Chen, W.; Zong, Y.; Geng, J.; Zhao, Y.; He, Z.; Du, R. Preparation, Characterization, and In Vitro Stability Analysis of Deer Sinew Peptide-Zinc Chelate. Foods 2025, 14, 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Guo, L.; Lao, L.; Ma, F.; Cao, Y.; Miao, J. Preparation, characterization and enhancement of intestinal iron absorption activity of β-casein phosphopeptides-iron chelate. Process Biochem. 2024, 146, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Zhao, C.; Cheng, C.; Huang, D.-c.; Cheng, S.-j.; Cao, C.-j.; Chen, G.-t. A peptide-Fe(II) complex from Grifola frondosa protein hydrolysates and its immunomodulatory activity. Food Biosci. 2019, 32, 100459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Yue, Y.; Guo, B.; Zhang, S.; Ji, C.; Chen, Y.; Dai, Y.; Dong, L.; Zhu, B.; Lin, X. Novel microbial fermentation for the preparation of iron-chelating scallop skirts peptides-its profile, identification, and possible binding mode. Food Chem. 2024, 451, 139493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- András, M.; Frank, W.; Linda, K.; Young-Ho, L.; Yuji, G.; Matthieu, R.; József, K. Accurate secondary structure prediction and fold recognition for circular dichroism spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E3095–E3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K.; Xiao, H.; Laihao, L.; Xianqing, Y.; Shengjun, C.; Yanyan, W.; Changhu, X. A novel zinc-binding peptide identified from tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) skin collagen and transport pathway across Caco-2 monolayers. Food Biosci. 2021, 42, 101127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, B.; Wang, B.; Xie, N. Degradation and antioxidant activities of peptides and zinc–peptide complexes during in vitro gastrointestinal digestion. Food Chem. 2015, 173, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Horizontal Numbering | Elements | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| A—Peptide–Zinc Mass Ratio | B—Zinc Source Concentration (mg/mL) | C—pH Value | |

| 1 | 7:1 | 24 | 6.5 |

| 2 | 8:1 | 28 | 7.0 |

| 3 | 9:1 | 32 | 7.5 |

| No. | Influence Factor | Rate of Chelation (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | ||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 32.63 ± 0.78 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 31.62 ± 0.62 |

| 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 33.52 ± 0.82 |

| 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 41.14 ± 1.89 |

| 5 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 32.25 ± 0.48 |

| 6 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 34.73 ± 0.55 |

| 7 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 31.49 ± 0.18 |

| 8 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 41.34 ± 0.23 |

| 9 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 36.83 ± 5.30 |

| K1 | 32.59 | 33.90 | 38.37 | |

| K2 | 36.04 | 34.75 | 34.39 | |

| K3 | 36.55 | 36.53 | 32.42 | |

| Range | 3.96 | 2.63 | 5.95 | |

| Sequence | C > A > B | |||

| Optimal level | A3 | B3 | C1 | |

| Types of Amino Acids | Relative Content (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| LMW DHGP | LMW DHGP–Zinc Chelates | |

| Asp | 7.60 | 8.98 |

| Glu | 15.13 | 16.92 |

| Gly | 23.00 | 23.51 |

| Ala | 10.62 | 9.88 |

| Val | 2.86 | 2.34 |

| Ile | 1.94 | 1.60 |

| Leu | 4.19 | 3.44 |

| Tyr | 1.27 | 0.92 |

| Phe | 2.65 | 2.11 |

| His | 0.86 | 1.03 |

| Lys | 4.58 | 4.72 |

| Arg | 9.75 | 10.22 |

| Pro | 15.41 | 14.16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Han, W.; Yang, L.; Fan, Y.; Lv, Y.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Liang, R. Zinc Chelates from Low-Molecular-Weight Donkey-Hide Gelatin Peptides: Preparation, Characterization, and Evaluation of In Vitro Antioxidant Activity. Foods 2025, 14, 3671. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213671

Han W, Yang L, Fan Y, Lv Y, Li X, Li Y, Li S, Liang R. Zinc Chelates from Low-Molecular-Weight Donkey-Hide Gelatin Peptides: Preparation, Characterization, and Evaluation of In Vitro Antioxidant Activity. Foods. 2025; 14(21):3671. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213671

Chicago/Turabian StyleHan, Wenxuan, Lili Yang, Yujie Fan, Yanyan Lv, Xiao Li, Yuhang Li, Siyu Li, and Rong Liang. 2025. "Zinc Chelates from Low-Molecular-Weight Donkey-Hide Gelatin Peptides: Preparation, Characterization, and Evaluation of In Vitro Antioxidant Activity" Foods 14, no. 21: 3671. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213671

APA StyleHan, W., Yang, L., Fan, Y., Lv, Y., Li, X., Li, Y., Li, S., & Liang, R. (2025). Zinc Chelates from Low-Molecular-Weight Donkey-Hide Gelatin Peptides: Preparation, Characterization, and Evaluation of In Vitro Antioxidant Activity. Foods, 14(21), 3671. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14213671