Analysis of the Relationship Between Personal Characteristics and Alcohol Consumption Behavior of Chinese Consumers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Basic Information

2.2.2. Personal Circumstances

2.3. Data Analysis

2.4. Statistical Analysis and Statistical Methods

3. Results

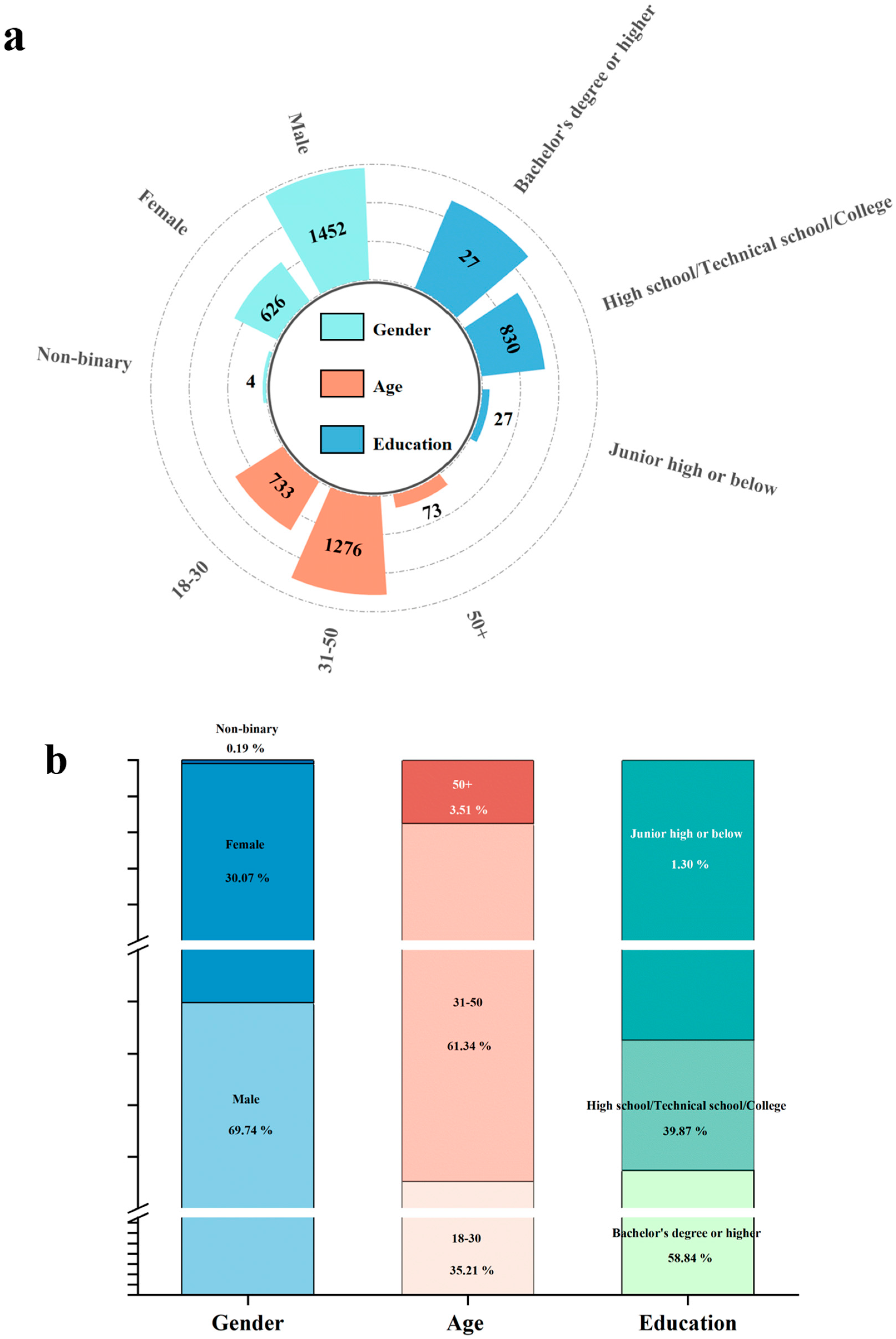

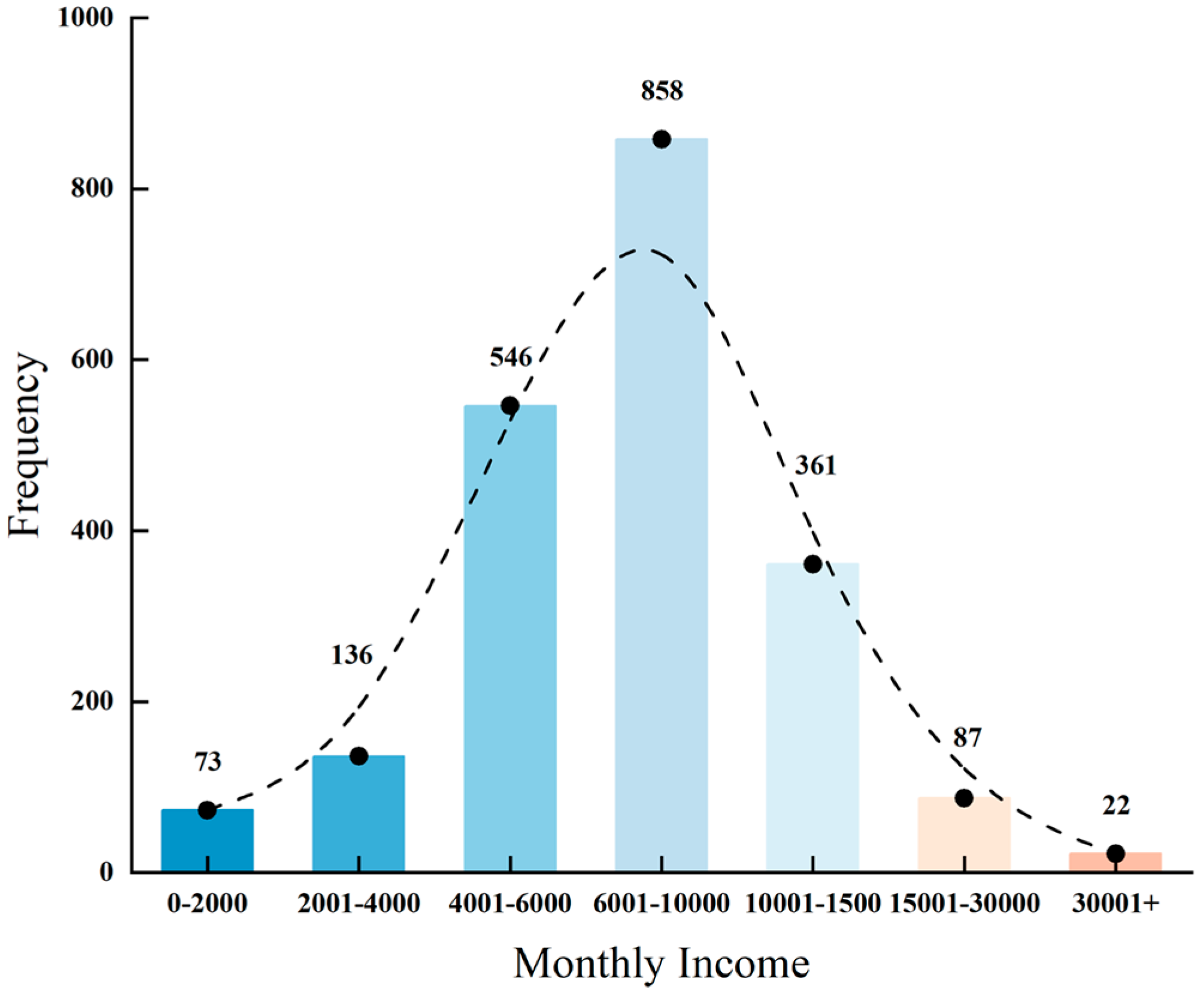

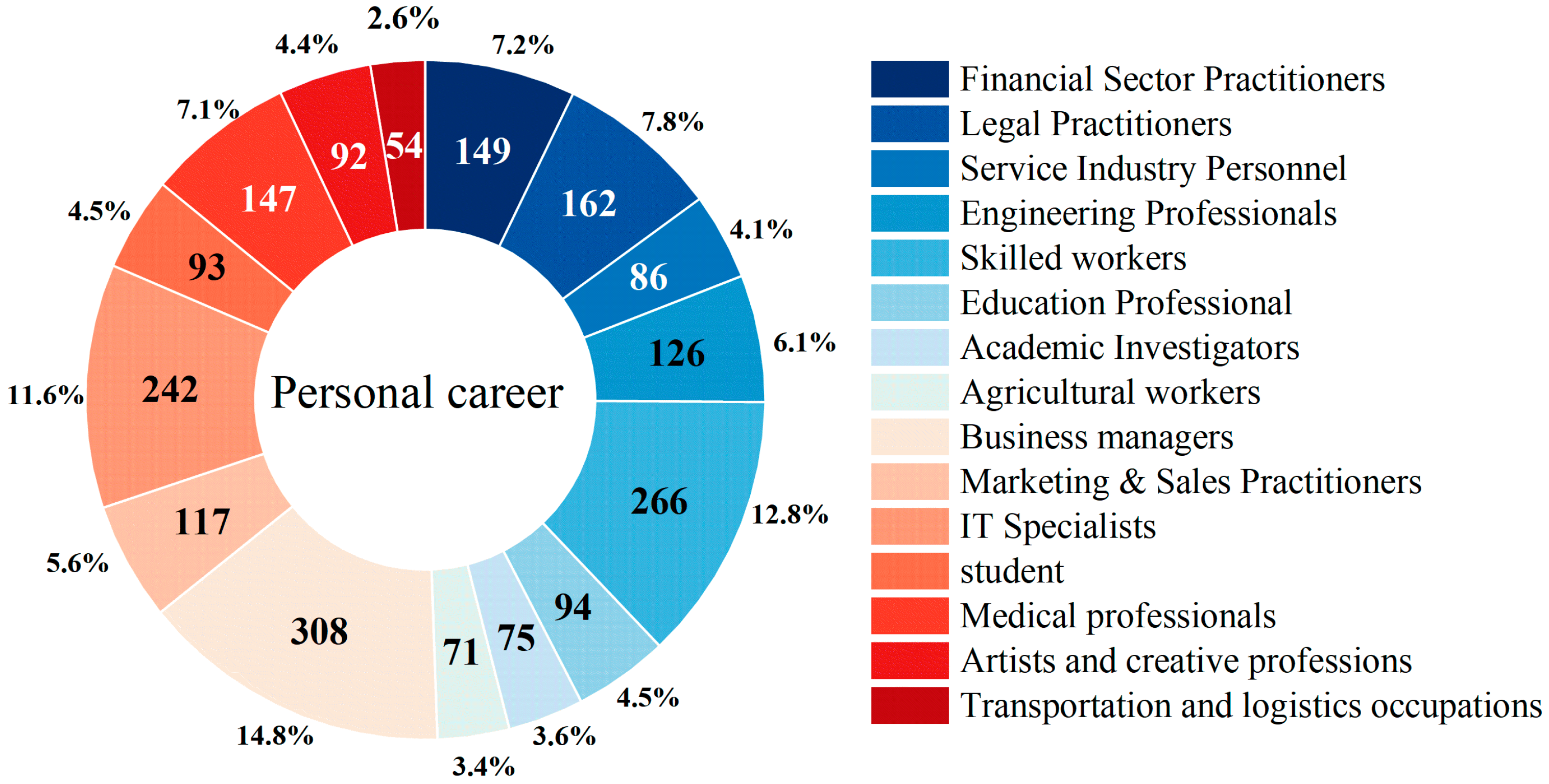

3.1. Sample Characteristics

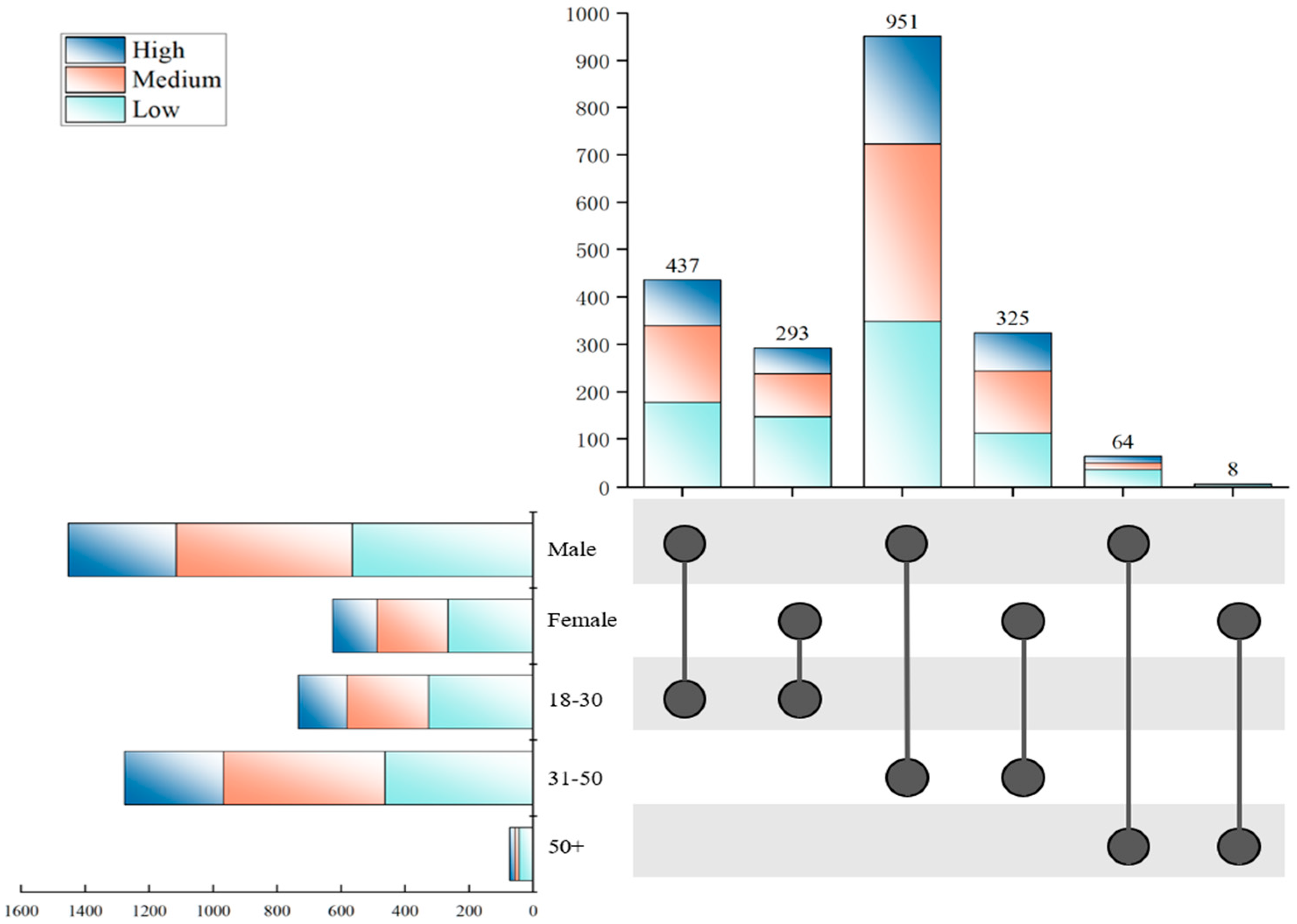

3.2. Characteristics of Drinking Consumption Behavior of Different Groups of Consumers

3.3. Exploration on the Link Between Personal Factors and Alcohol Consumption Behavior

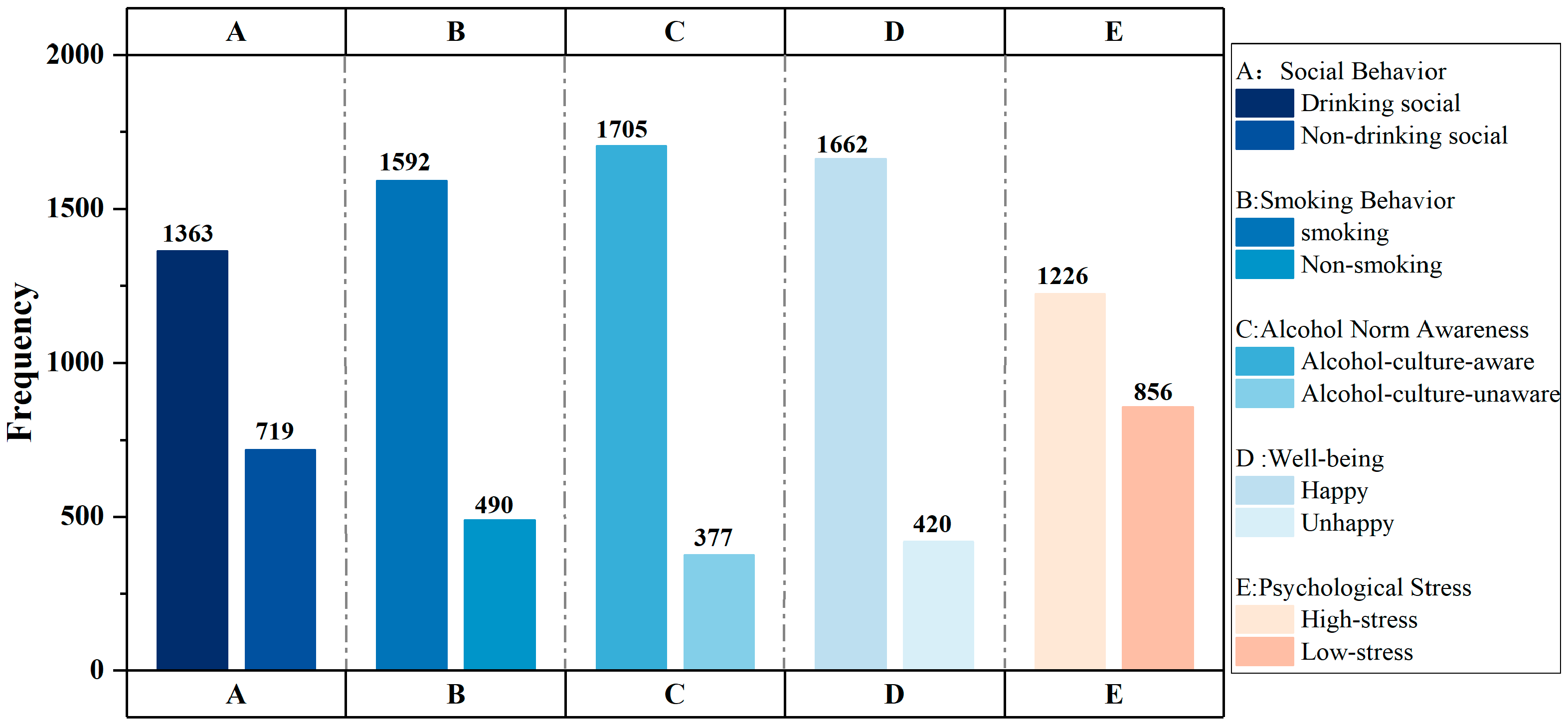

3.3.1. Descriptive Analysis of Personal Factors

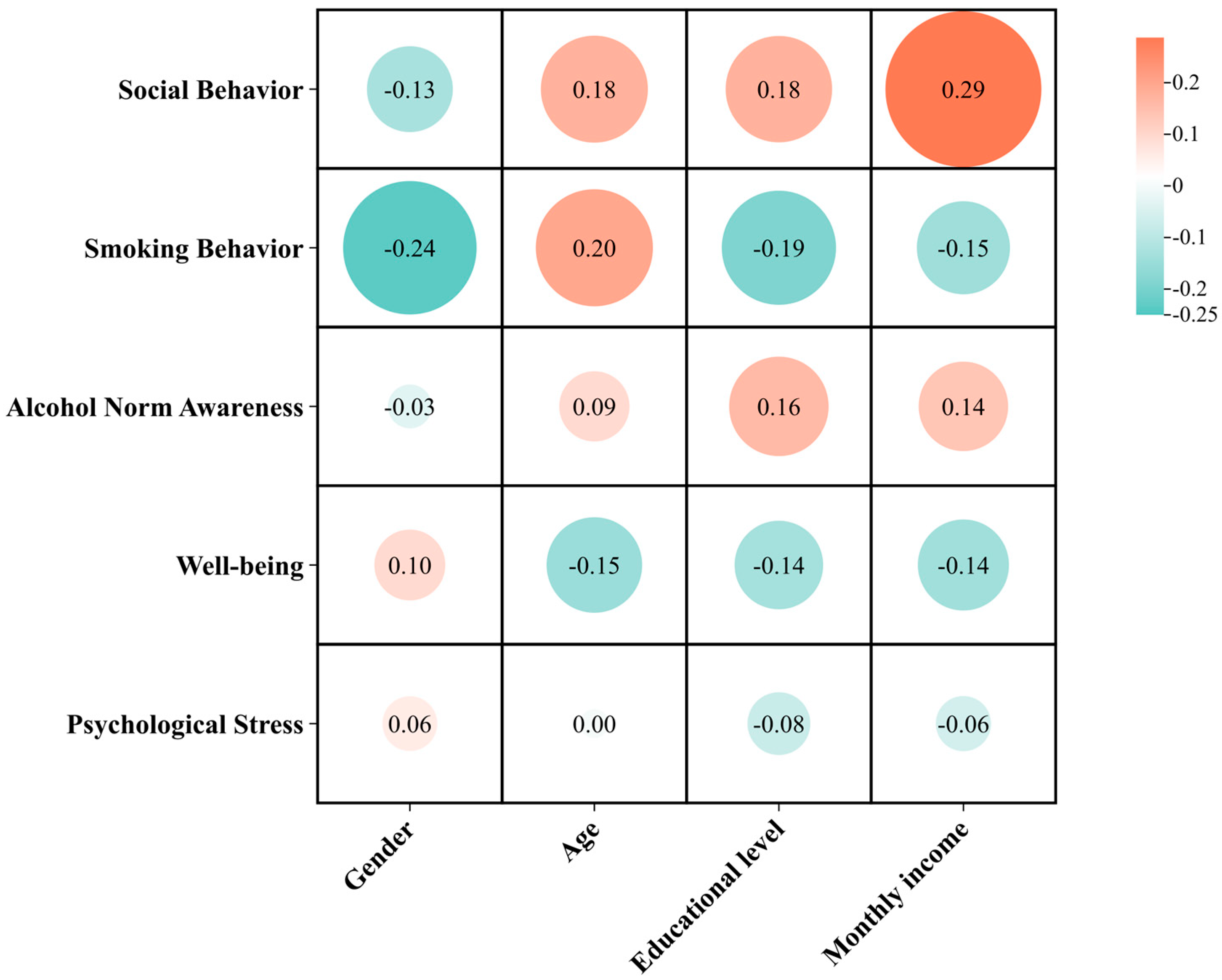

3.3.2. Analysis of Correlations Between Basic Information and Personal Factors

3.3.3. Analysis of Drinking Frequency Distribution Across Consumer Personal Factors

3.3.4. Preliminary Analysis of Personal Factors on Drinking Frequency

3.4. The Influence of Personal Factors on the Frequency of Alcohol Consumption

4. Discussion

4.1. Drinking Frequency Across Different Personal Profiles

4.2. Personal Factors Associated with Drinking Frequency

4.3. Research Contributions and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| AMEs | SE | 95% CI | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medium | Drinking social vs. Non-drinking social | 0.008 | 0.024 | −0.038 | 0.054 | 0.734 |

| Smoking vs. Non-smoking | 0.015 | 0.025 | −0.033 | 0.063 | 0.543 | |

| Alcohol culture vs. None | 0.005 | 0.030 | −0.053 | 0.063 | 0.867 | |

| Happy vs. Unhappy | 0.052 | 0.028 | −0.002 | 0.106 | 0.062 | |

| Low-stress vs. High-stress | 0.038 | 0.022 | −0.004 | 0.080 | 0.080 | |

| High | Drinking social vs. Non-drinking social | 0.012 | 0.019 | −0.024 | 0.048 | 0.518 |

| Smoking vs. Non-smoking | 0.042 | 0.021 | 0.001 | 0.083 | 0.043 | |

| Alcohol culture vs. None | 0.041 | 0.023 | −0.004 | 0.086 | 0.072 | |

| Happy vs. Unhappy | −0.035 | 0.019 | −0.072 | 0.002 | 0.062 | |

| Low-stress vs. High-stress | 0.118 | 0.025 | 0.069 | 0.167 | <0.001 | |

References

- Lin, M.; Yang, B.; Dai, M.; Xu, Y.; Li, X.; Sun, B. East meets west in alcoholic beverages: Flavor comparison, microbial metabolism and health effects. Food Biosci. 2023, 56, 103385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mall, V.; Schieberle, P. On the importance of Phenol Derivatives for the Peaty Aroma Attribute of Scotch Whiskies from Islay. In Sex, Smoke, and Spirits: The Role of Chemistry; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Volume 1321, pp. 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Harutyunyan, M.; Malfeito-Ferreira, M. The Rise of Wine among Ancient Civilizations across the Mediterranean Basin. Heritage 2022, 5, 788–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirístová, L.; Prinosilová, S.; Riddellová, K.; Hajšlová, J.; Melzoch, K. Changes in quality parameters of vodka filtered through activated charcoal. Czech J. Food Sci. 2012, 30, 474–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herkenhoff, M.E.; Brödel, O.; Frohme, M. Aroma component analysis by HS-SPME/GC–MS to characterize Lager, Ale, and sour beer styles. Food Res. Int. 2024, 194, 114763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Hong, J.; Huang, H.; Zhao, D.; Sun, B.; Sun, J.; Huang, M.; Sun, X. Based on metabolomics, chemometrics, and modern separation omics: Identifying key in-pathway and out-pathway points for pesticide residues during solid-state fermentation of baijiu. Food Chem. 2024, 451, 138767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Guo, J. Functionalized Carbon-Based Electrochemical Sensors for Food and Alcoholic Beverage Safety. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Deng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, B.; Li, W.; Dong, W.; Sun, X. Applications of Microextraction Technology for the Analysis of Alcoholic Beverages Quality: Current Perspectives and Future Directions. Foods 2025, 14, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, D. Uncover the flavor code of strong-aroma baijiu: Research progress on the revelation of aroma compounds in strong-aroma baijiu by means of modern separation technology and molecular sensory evaluation. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2022, 109, 104499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pascale, A.; Lanfranchi, M.; Zanchini, R.; Giannetto, C.; D’Amico, M.; Di Vita, G. Craft beer preferences among digitarians in Italy. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2024, 36, 207–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Multi-sensor temperature and humidity control system of wine cellar based on cooperative control of intelligent vehicle and UAV. Int. J. Comput. Appl. Technol. 2021, 67, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wan, B.; Yang, F.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Du, G.; Wang, L.; Chen, J. Metabolomics-Driven Elucidation of Interactions between Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Lactobacillus panis from Chinese Baijiu Fermentation Microbiome. Fermentation 2022, 8, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, Z.; Cai, X.; Liu, J.; Fan, R.; Tang, J.; Luo, A. Elucidation of the key aroma compounds of floral and fruity aroma in sauce-flavored Baijiu by pervaporative membrane separation, GC-IMS, GC-MS, and Aroma Omission Studies. Food Biosci. 2025, 66, 106270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Yin, R.; Xie, J.; Hong, J.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, X.; Guo, L.; Song, Y.; Zhao, D.; et al. Exploring the key effects of non-volatile acid compounds on the expression of dominant flavor in lager beer using flavor matrix and molecular docking. LWT 2025, 229, 118177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandha, J.; Shumoy, H.; Devaere, J.; Schouteten, J.J.; Gellynck, X.; de Winne, A.; Matemu, A.O.; Raes, K. Effect of lactic acid fermentation of watermelon juice on its sensory acceptability and volatile compounds. Food Chem. 2021, 358, 129809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.J.; Antonelli, M. Conceptual Models of Food Choice: Influential Factors Related to Foods, Individual Differences, and Society. Foods 2020, 9, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KöSter, E.P. Diversity in the determinants of food choice: A psychological perspective. Food Qual. Prefer. 2007, 20, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yin, R.; Guo, L.; Zhao, D.; Sun, B. Development and Validation of a Consumer-Oriented Sensory Evaluation Scale for Pale Lager Beer. Foods 2025, 14, 2834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micek, A.; Alshatwi, A.A.; Paladino, N.; Guerrera, I.; Grosso, G.; Castellano, S.; Godos, J. Association between alcoholic (poly)phenol-rich beverage consumption and cognitive status in older adults living in a Mediterranean area. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 74, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuss, T.; Morley, B.; Scully, M.; Wakefield, M. Energy drink consumption among Australian adolescents associated with a cluster of unhealthy dietary behaviours and short sleep duration. Nutr. J. 2021, 20, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camillo, A.A.; Kim, W.G.; Asatryan, E. Consumption Behavior of the Internet Active Armenian Wine Consumer. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2023, 35, 622–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, F.F.; Ribeiro, A.P.L.; Vieira, K.C.; Pereira, R.C.; Carneiro, J.D.S. Specialty beers market: A comparative study of producers and consumers behavior. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 1282–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucha, L.; Vámosi, K.; Totth, G. Examining the factors shaping consumer attitude towards the popular alcoholic beverages in Hungary. Heliyon 2022, 8, 10571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClain, P.; Zamboanga, B.L.; Ramarushton, B.; Walukevich-Dienst, K.; Thompson, L.; Ford, K.; Blumenthal, H.; Ham, L.S.; Bartholomew, J.; Michikyan, M.; et al. Pregaming in the digital age: Drinking before joining a virtual social event with friends or family among university students. Curr. Psychol. 2025, 44, 10311–10321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M.J.; Stevens, A.K.; Janssen, T.; Jackson, K.M. Event-level contextual predictors of high-intensity drinking events among young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022, 239, 109590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molaeipour, L.; Ghalandari, M.; Kangavari, H.N.; Alizadeh, Z.; Jafari, E.; Gholami, F.; Ghahremanzadeh, N.; Safari, S.; Mohseni, V.; Shahsavan, M.; et al. The association between current smoking and binge drinking among adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 1084762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilatti, A.; Klein, N.D.; Mezquita, L.; Bravo, A.J.; Keough, M.T.; Pautassi, R.M. Drinking Motives as Mediators of the Relationship of Cultural Orientation with Alcohol Use and Alcohol-Related Negative Consequences in College Students from Seven Countries. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 21, 3238–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, A.S.P.; Pisinger, V.; Krarup, A.F.; Dalum, P.; Thygesen, L.C.; Tolstrup, J.S. Alcohol consumption and well-being among 25,000 Danish high school students. Prev. Med. Rep. 2023, 31, 102072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueno, M. Relationships between drinking habits, psychological resilience, and salivary cortisol responses on the Trier Social Stress Test-Online among Japanese people. BMC Psychol. 2023, 11, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehayes, I.L.L.; Mackinnon, S.P.; Sherry, S.B.; Leonard, K.E.; Stewart, S.H. Drinking motives and drinking behaviors in romantic couples: A longitudinal actor-partner interdependence model. Psychology of addictive behaviors J. Soc. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2019, 33, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.J.; Ho, S.Y.; Leung, L.T.; Wang, M.P.; Lam, T.H. Associations of unhappiness with sociodemographic factors and unhealthy behaviours in Chinese adolescents. Eur. J. Public Health 2017, 27, 518–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiano, A. Craft beer: An overview. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 20, 1829–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadini, G.; Fumi, M.D.; DeFaveri, M.D.; De Faveri, M.D. How Foam Appearance Influences the Italian Consumer’s Beer Perception and Preference. J. Inst. Brew. 2011, 117, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, N.B.; Minim, L.A.; Nascimento, M.; Ferreira, G.H.d.C.; Minim, V.P.R. Characterization of the consumer market and motivations for the consumption of craft beer. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, A.; Quici, L. Craft beer mon amour: An exploration of Italian craft consumers. Br. Food J. 2020, 122, 2671–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurnell-Read, T. ‘Did you ever hear of police being called to a beer festival?’ Discourses of merriment, moderation and ‘civilized’ drinking amongst real ale enthusiasts. Sociol. Rev. 2017, 65, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Shon, C.; Kim, K. Drinking Norms and Drinking Behavior: Alcohol Expectancy as a Mediator. Health Soc. Welf. Rev. 2024, 44, 178–196. [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrovski, D.; Joukes, V.; Scott, N. Food and wine presence and pairing within traditional restaurants’ menus as regional heritage promotional behaviour: Gemeinschaft or Gesellschaft? J. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 32, 2644–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HernándezMora, Y.N.; VerdeCalvo, J.R.; MalpicaSánchez, F.P.; Escalona-Buendía, H.B. Consumer Studies: Beyond Acceptability—A Case Study with Beer. Beverages 2022, 8, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Alcohol Consumption Frequency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High | ||

| Gender | Male | 565 (38.91%) | 550 (37.88%) | 337 (23.21%) |

| Female | 265 (42.33%) | 222 (35.46%) | 139 (22.20%) | |

| Non-binary | 1 (25.00%) | 2 (50.00%) | 1 (25.00%) | |

| Age | 18–30 | 326 (44.47%) | 255 (34.79%) | 152 (20.74%) |

| 31–50 | 462 (36.21%) | 505 (39.58%) | 309 (24.21%) | |

| 50+ | 43 (58.90%) | 14 (19.18%) | 16 (21.92%) | |

| Total (n) | 831 (39.91%) | 774 (37.18%) | 477 (22.91%) | |

| Low | Medium | High | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drinking social | 557 (40.87%) | 494 (36.24%) | 312 (22.89%) | 1.179 |

| Non-drinking social | 274 (38.11%) | 280 (38.94%) | 165 (22.95%) | |

| smoking | 604 (37.94%) | 593 (37.25%) | 395 (24.81%) | 1.047 |

| Non-smoking | 227 (46.33%) | 181 (36.94%) | 82 (16.73%) | |

| Alcohol-culture-aware | 704 (41.29%) | 634 (37.14%) | 367 (21.52%) | 1.154 |

| Alcohol-culture-unaware | 127 (33.69%) | 140 (37.14%) | 110 (29.18%) | |

| Happy | 644 (38.75%) | 665 (40.01%) | 353 (21.24%) | 1.076 |

| Unhappy | 187 (44.52%) | 109 (25.95%) | 124 (29.52%) | |

| High-stress | 404 (32.95%) | 459 (37.44%) | 363 (29.61%) | 1.043 |

| Low-stress | 427 (49.88%) | 315 (36.80%) | 114 (13.32%) |

| 95% CI for (Exp(B)) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Consumption Frequency | B | Wald X2 | p | Exp(B) | Lower | Upper | |

| Medium | −0.802 | 12.578 | <0.001 | ||||

| Drinking social | 0.039 | 0.116 | 0.733 | 1.040 | 0.831 | 1.301 | |

| Non-drinking social | 0 b | ||||||

| smoking | 0.144 | 1.480 | 0.224 | 1.155 | 0.916 | 1.458 | |

| Non-smoking | 0 b | ||||||

| Alcohol-culture-aware | 0.046 | 0.102 | 0.749 | 1.047 | 0.790 | 1.389 | |

| Alcohol-culture-unaware | 0 b | ||||||

| Happy | 0.527 | 14.698 | <0.001 | 1.693 | 1.294 | 2.217 | |

| Unhappy | 0 b | ||||||

| High-stress | 0.379 | 13.442 | <0.001 | 1.460 | 1.193 | 1.788 | |

| Low-stress | 0 b | ||||||

| High | −1.126 | 18.602 | <0.001 | ||||

| Drinking social | 0.178 | 1.692 | 0.193 | 1.195 | 0.914 | 1.562 | |

| Non-drinking social | 0 b | ||||||

| smoking | 0.417 | 7.671 | 0.006 | 1.517 | 1.130 | 2.037 | |

| Non-smoking | 0 b | ||||||

| Alcohol-culture-aware | 0.423 | 6.894 | 0.009 | 1.526 | 1.113 | 2.092 | |

| Alcohol-culture-unaware | 0 b | ||||||

| Happy | −0.376 | 6.752 | 0.009 | 0.687 | 0.517 | 0.912 | |

| Unhappy | 0 b | ||||||

| High-stress | 1.195 | 83.287 | <0.001 | 3.303 | 2.556 | 4.270 | |

| Low-stress | 0 b | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yuan, X.; Chen, Y.; Yin, R.; Guo, L.; Song, Y.; Zhong, B.; Zhao, D. Analysis of the Relationship Between Personal Characteristics and Alcohol Consumption Behavior of Chinese Consumers. Foods 2025, 14, 3536. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14203536

Yuan X, Chen Y, Yin R, Guo L, Song Y, Zhong B, Zhao D. Analysis of the Relationship Between Personal Characteristics and Alcohol Consumption Behavior of Chinese Consumers. Foods. 2025; 14(20):3536. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14203536

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Xin, Yiyuan Chen, Ruiyang Yin, Liyun Guo, Yumei Song, Bofeng Zhong, and Dongrui Zhao. 2025. "Analysis of the Relationship Between Personal Characteristics and Alcohol Consumption Behavior of Chinese Consumers" Foods 14, no. 20: 3536. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14203536

APA StyleYuan, X., Chen, Y., Yin, R., Guo, L., Song, Y., Zhong, B., & Zhao, D. (2025). Analysis of the Relationship Between Personal Characteristics and Alcohol Consumption Behavior of Chinese Consumers. Foods, 14(20), 3536. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14203536