Assessment of Food Hygiene Non-Compliance and Control Measures: A Three-Year Inspection Analysis in a Local Health Authority in Southern Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Tourism-driven demand: The intense seasonal pressure on food businesses can lead to overburdened facilities, the hiring of temporary and less-trained staff, and shortcuts in hygiene procedures to meet high demand.

- Heterogeneous food production: The prevalence of small, family-run businesses often utilizing traditional methods may coexist with a lack of resources for structural investments, leading to infrastructural deficiencies that require long-term corrective actions.

- Socioeconomic disparities: Economic pressures may disincentivize investments in modern equipment, staff training, and robust self-control systems, making compliance a secondary priority for some operators.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

2.2. Inspection Procedures

- General requirements for food premises (e.g., layout, design, construction, site, and size);

- Specific requirements in rooms where foodstuffs are prepared, treated, or processed (e.g., floors, walls, ceilings, windows, ventilation);

- Requirements for transport;

- Equipment requirements (e.g., materials in contact with food, cleaning procedures, maintenance);

- Food waste management;

- Water supply;

- Personal hygiene (e.g., training, cleanliness, and health status of food handlers);

- Provisions applicable to foodstuffs (e.g., temperature control, prevention of cross-contamination);

- Provisions applicable to the wrapping and packaging of foodstuffs;

- Training of personnel.

2.3. Types of Non-Compliances and Sanctions

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Statement

3. Results

3.1. Overview of the Sample

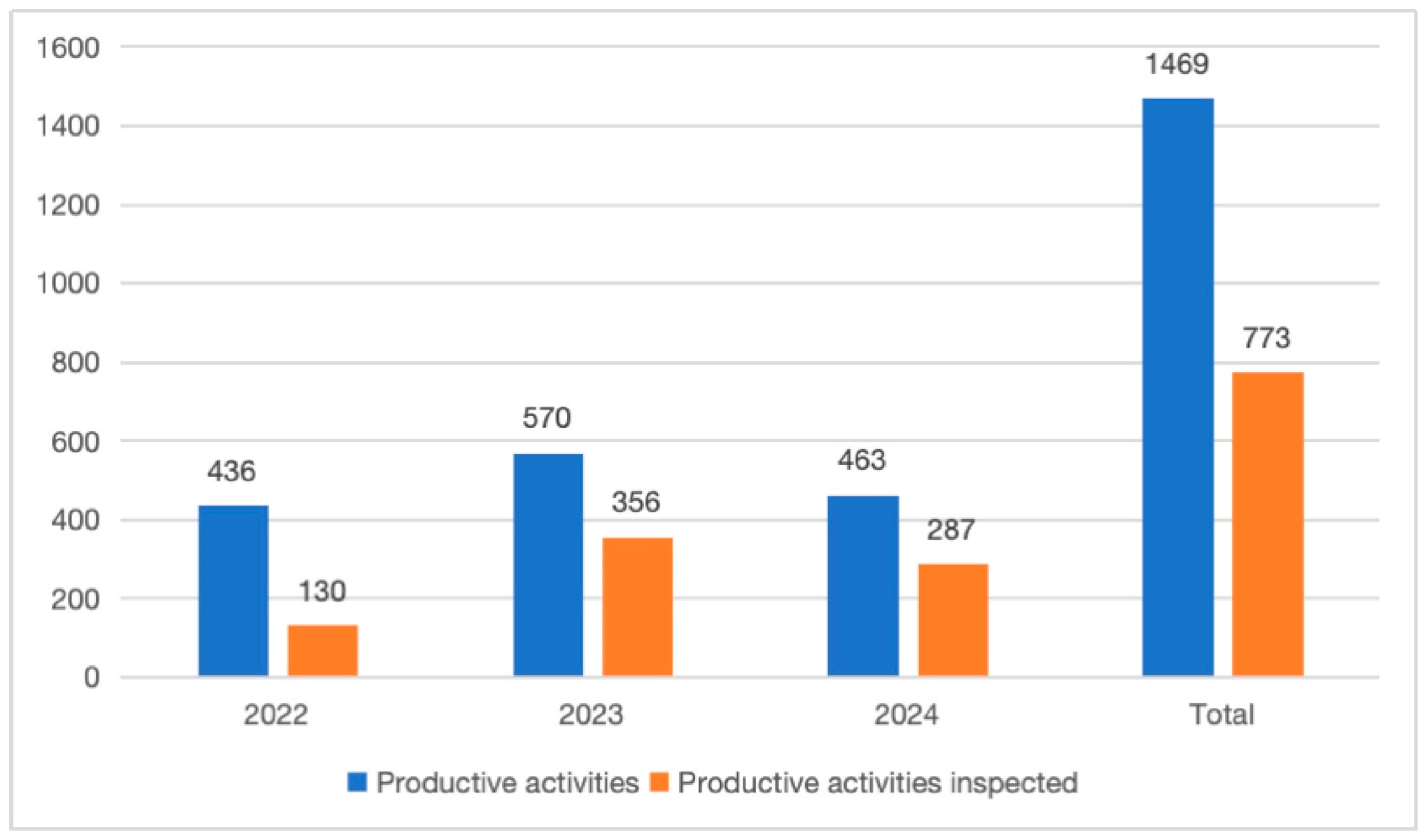

3.2. Inspection Trends Across the Three-Year Period

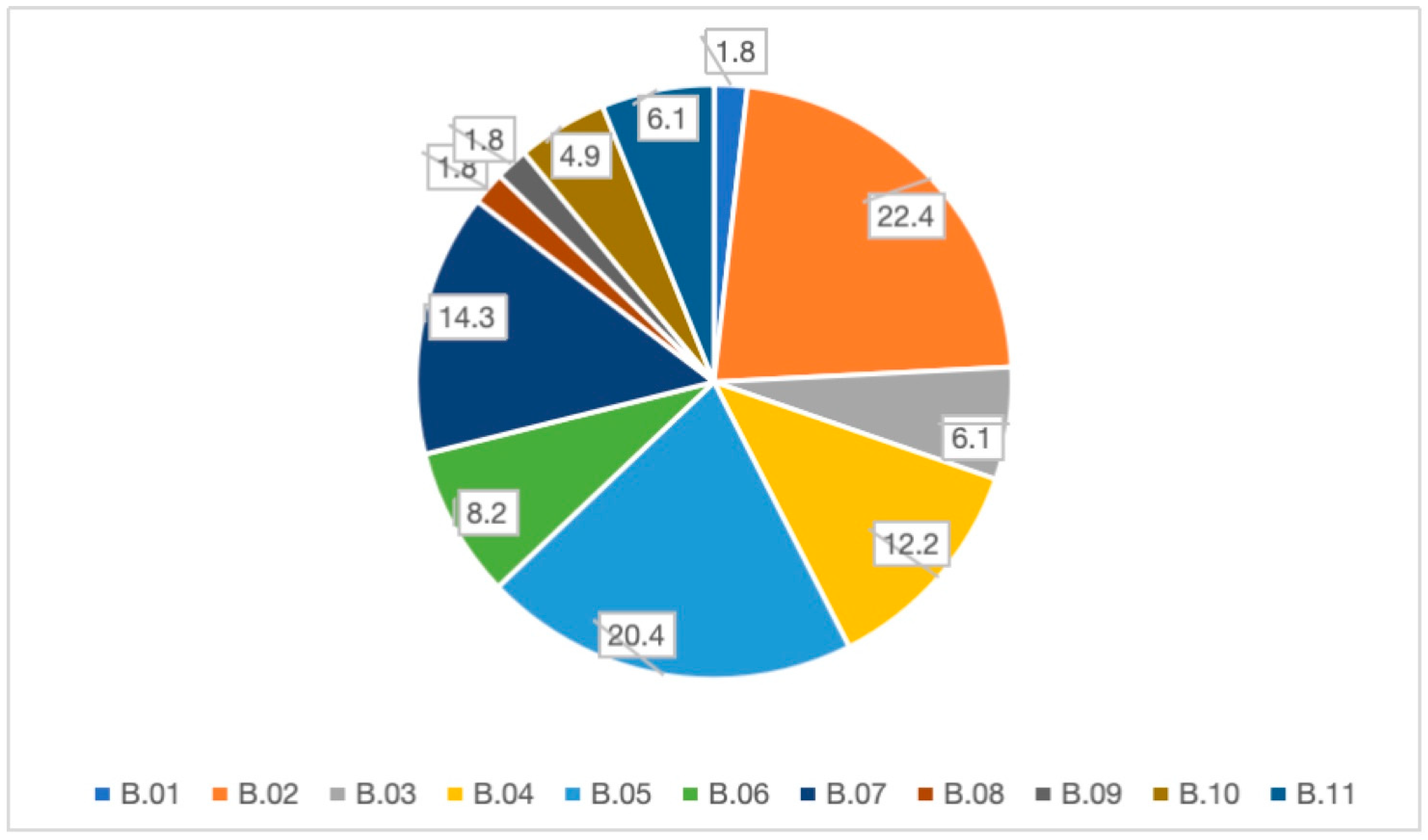

3.3. Reasons for Inspections

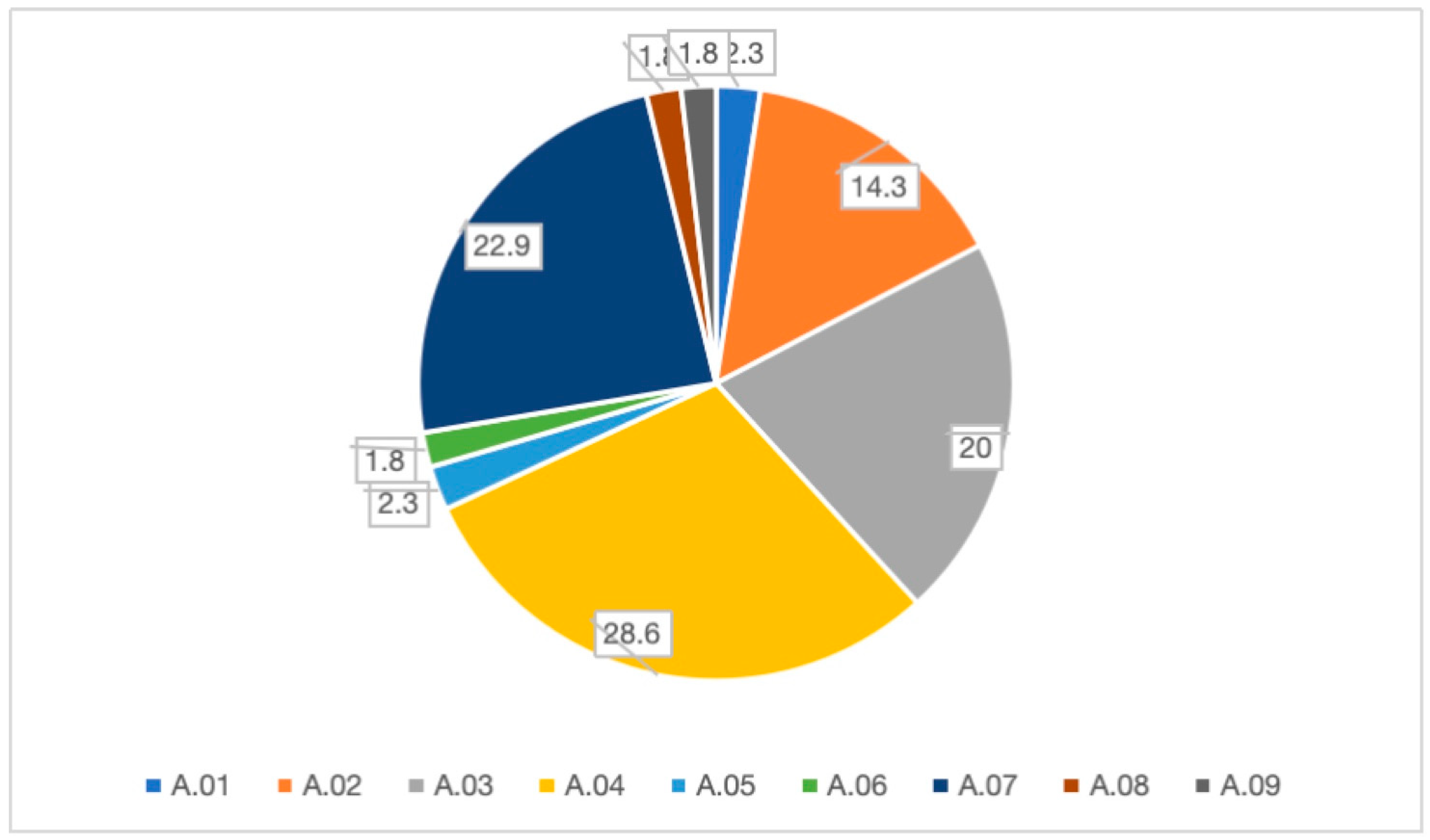

3.4. Measures Adopted During Inspections

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Food Safety; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/food-safety (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Cervantes, P.L.; Xicotencatl, R.I.F.; Cador, C.M.; Kinney, I.S. Circular economy and food safety: A focus on ONE health. Appl. Food Res. 2024, 4, 100509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizaw, Z. Public health risks related to food safety issues in the food market: A systematic literature review. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2019, 24, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bevilacqua, A.; De Santis, A.; Sollazzo, G.; Speranza, B.; Racioppo, A.; Sinigaglia, M.; Corbo, M.R. Microbiological Risk Assessment in Foods: Background and Tools, with a Focus on Risk Ranger. Foods 2023, 12, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ellahi, R.M.; Wood, L.C.; Bekhit, A.E.-D.A. Blockchain-Based Frameworks for Food Traceability: A Systematic Review. Foods 2023, 12, 3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Shi, Q.; Zhou, N. Construction of a Traceability System for Food Industry Chain Safety Information Based on Internet of Things Technology. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 857039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tibebu, A.; Tamrat, H.; Bahiru, A. Review: Impact of food safety on global trade. Vet. Med. Sci. 2024, 10, e1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- European Commission. Food Hygiene—Legislation. European Commission, Food Safety Website. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/food-safety/biological-safety/food-hygiene/legislation_en (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Official Controls and Enforcements. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/horizontal-topics/official-controls-and-enforcement_en (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Lugli, C.; Cecchini, M.; Maione, D.; Marseglia, F.; Filippini, T.; Vinceti, M.; Righi, E.; Palandri, L.; De Vita, D. Italian adaptation to Regulation (EU) 2017/625 on food official controls: A case study. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2024, 13, 12543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifedinezi, O.V.; Nnaji, N.D.; Anumudu, C.K.; Ekwueme, C.T.; Uhegwu, C.C.; Ihenetu, F.C.; Obioha, P.; Simon, B.O.; Ezechukwu, P.S.; Onyeaka, H. Environmental Antimicrobial Resistance: Implications for Food Safety and Public Health. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pai, A.S.; Jaiswal, S.; Jaiswal, A.K. A Comprehensive Review of Food Safety Culture in the Food Industry: Leadership, Organizational Commitment, and Multicultural Dynamics. Foods 2024, 13, 4078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigłowski, M.; Śmiechowska, M. Notifications Related to Fraud and Adulteration in the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) in 2000–2021. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, L.; Soon, J.M. Food Safety, Food Fraud, and Food Defense: A Fast Evolving Literature. J. Food Sci. 2016, 81, R823–R834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popping, B.; Buck, N.; Bánáti, D.; Brereton, P.; Gendel, S.; Hristozova, N.; Chaves, S.M.; Saner, S.; Spink, J.; Willis, C.; et al. Food inauthenticity: Authority activities, guidance for food operators, and mitigation tools. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 4776–4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulberth, F. Tools to combat food fraud—A gap analysis. Food Chem. 2020, 330, 127044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radu, E.; Dima, A.; Dobrota, E.M.; Badea, A.M.; Madsen, D.Ø.; Dobrin, C.; Stanciu, S. Global trends and research hotspots on HACCP and modern quality management systems in the food industry. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Traversa, A.; Rubinetti, F.; Lanzilli, S.; Bervini, R.; Bruatto, G.; Coruzzi, E.; Gilli, M.; Mendolicchio, A.; Osella, E.; Stassi, E.; et al. Official food safety audits in large scale retail trades in the time of COVID: System control experiences supported by an innovative approach. Ital. J. Food Saf. 2022, 11, 10022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sorbo, A.; Pucci, E.; Nobili, C.; Taglieri, I.; Passeri, D.; Zoani, C. Food Safety Assessment: Overview of Metrological Issues and Regulatory Aspects in the European Union. Separations 2022, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.-A. Special Issue: Food Safety Management and Quality Control Techniques. Processes 2024, 12, 2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čapla, J.; Zajác, P.; Čurlej, J.; Benešová, L.; Jakabová, S.; Fikselová, M.; Bobková, A. Analysis of data from the rapid alert system for food and feed for the country-of-origin Slovakia for 2002–2020. Heliyon 2023, 10, e23146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- European Commission. Administrative Assistance and Cooperation Network (AAC). Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/food-safety/aac_en (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- European Commission. EU Agri-Food Fraud Network (FFN). Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/food-safety/eu-agri-food-fraud-network_en (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Baldino, G.; Genovese, C.; Genovese, G.; Burrascano, G.; Asmundo, A.; Gualniera, P.; Ventura Spagnolo, E. Analysis of the contentious relating to medical liability for healthcare-associated infections (HAI) in a Sicilian hospital. Clin. Ter. 2024, 175, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzo, C.E.; Venuto, R.; Tripodi, P.; Bartucciotto, L.; Ventura Spagnolo, E.; Nirta, A.; Genovese, G.; La Spina, I.; Sortino, S.; Nicita, A.; et al. From Guidelines to Action: Tackling Risk Factors for Surgical Site Infections. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loddo, F.; Laganà, P.; Rizzo, C.E.; Calderone, S.M.; Romeo, B.; Venuto, R.; Maisano, D.; Fedele, F.; Squeri, R.; Nicita, A.; et al. Intestinal Microbiota and Vaccinations: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Vaccines 2025, 13, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facciolà, A.; Laganà, A.; Genovese, G.; Romeo, B.; Sidoti, S.; D’Andrea, G.; Raco, C.; Visalli, G.; Di Pietro, A. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the infectious disease epidemiology. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2023, 64, E274–E282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laganà, A.; Saia, I.; Genovese, G.; Visalli, G.; D’Andrea, G.; Sidoti, S.; Di Pietro, A.; Facciolà, A. Resurgence of scabies in Italy: The new life of an old disease. Parasite Epidemiol. Control 2024, 27, e00392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, C.; Gorgone, M.; Genovese, G.; Spada, G.L.A.; Balsamo, D.; Calderone, S.M.; Faranda, I.; Squeri, R. Trend of pathogens and respiratory co-infections in the province of Messina: From pediatric age to senescence. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2024, 65, E346–E357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genovese, C.; La Fauci, V.; Costa, G.B.; Buda, A.; Nucera, S.; Antonuccio, G.M.; Alessi, V.; Carnuccio, S.; Cristiano, P.; Laudani, N.; et al. A potential outbreak of measles and chickenpox among healthcare workers in a university hospital. Euro Mediterr. Biomed. J. 2019, 14, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squeri, R.; La Fauci, V.; Picerno, I.A.M.; Trimarchi, G.; Cannavò, G.; Egitto, G.; Cosenza, B.; Merlina, V.; Genovese, C. Evaluation of Vaccination Coverages in the Health Care Workers of a University Hospital in Southern Italy. Ann. Ig. 2019, 31 (Suppl. 1), 13–24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- La Fauci, V.; Squeri, R.; Genovese, C.; Anzalone, C.; Fedele, F.; Squeri, A.; Alessi, V. An observational study of university students of healthcare area: Knowledge, attitudes and behaviour towards vaccinations. Clin. Ter. 2019, 170, e448–e453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrera, G.; Squeri, R.; Genovese, C. The evolution of vaccines for early childhood: The MMRV. Ann. Ig. 2018, 30 (Suppl. 1), 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genovese, G.; Rizzo, C.E.; Nirta, A.; Bartucciotto, L.; Venuto, R.; Fedele, F.; Squeri, R.; Genovese, C. Mapping Healthcare Needs: A Systematic Review of Population Stratification Tools. Med. Sci. 2025, 13, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Krishnaswamy, K.; Mustapha, A. Hazard Analysis and Risk-Based Preventive Controls (HARPC): Current Food Safety and Quality Standards for Complementary Foods. Foods 2021, 10, 2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venuto, R.; D’Amato, S.; Genovese, C.; Squeri, R.; Trimarchi, G.; Mazzitelli, F.; Pappalardo, R.; La Fauci, V. How sizeable are the knowledge, attitude and perception of food risks among young adults? An Italian survey. Epidemiol. Prev. 2024, 48, 40–47. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type of Non-Compliance | Risk Level | Examples | Action Required | Relevant Regulations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serious Non-Compliance | Immediate risk to health | - Dangerous pathogens (Salmonella, Listeria, E. coli) - Chemical contamination (pesticides) - Poor hygienic conditions | Immediate suspension, product withdrawal, fines, criminal penalties | Reg. (EC) No. 852/2004 (Hygiene of foodstuffs) Reg. (EC) No. 178/2002 (General food law) |

| Minor Non-Compliance | No immediate risk to health | - Incorrect labeling - Minor HACCP documentation issues - Small temperature deviations | Corrective measures, administrative sanctions | Reg. (EC) No. 178/2002 (Food safety management) Legislative Decree No. 190/2006 |

| Inadequacies | Potential future risk | - Poor maintenance of equipment - Inadequate staff training - Weak HACCP plan application | Address weaknesses, preventive measures | Reg. (EC) No. 852/2004 (Hygiene of foodstuffs) Art. 5 of Reg. 852/2004 (Food safety management system) |

| Code | Reason for Inspection | Description |

|---|---|---|

| B.01 | Joint control with Border Inspection Posts (BIPs, in Italian PIF) | Inspections carried out in collaboration with border control facilities, typically focusing on imported food products. |

| B.02 | RASFF | Inspections initiated following notifications from the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed, targeting urgent food safety risks. |

| B.03 | Health constraint | Inspections due to specific public health concerns, such as outbreaks or suspected contamination events. |

| B.04 | Official control after the report of Anti-adulteration and Health Units of the Carabinieri police (in Italian NAS, Comando Carabinieri per la Tutela della Salute) | Inspections following alerts from the Carabinieri’s Anti-Adulteration and Health Units (NASs), usually linked to suspected fraud or serious violations. |

| B.05 | Official routine control | Scheduled, preventive inspections carried out as part of the LHA’s regular monitoring activities. |

| B.06 | Joint official control with various law enforcement agencies | Inspections coordinated with non-specialized police or other regulatory bodies to address cross-sector issues. |

| B.07 | Official control for the verification of prescriptions | Follow-up inspections to ensure that previously issued corrective measures have been implemented. |

| B.08 | Joint official control with the Service for prevention and safety in the workplace (in Italian SPISAL or SPRESAL, Servizio per la prevenzione e la sicurezza negli ambienti di lavoro) | Inspections conducted together with occupational health and safety authorities, often in settings where hygiene overlaps with worker safety. |

| B.09 | Goods destruction | Inspections associated with the disposal of unsafe products, ensuring proper handling and compliance with regulations. |

| B.10 | Official block | Inspections resulting from, or aiming to impose, a formal halt on certain operations or product movements. |

| B.11 | Joint official control with SVET (Veterinary Service) | Inspections carried out with veterinary authorities, particularly for products of animal origin. |

| Code | Description | Measures Taken |

|---|---|---|

| A.01 | A drastic measure applied in cases of immediate risk to public health (e.g., severe microbiological or chemical contamination). It indicates a critical failure in preventive measures. | Goods destruction |

| A.02 | A positive outcome, showing that the operator has implemented the corrections required in previous inspections. | Previous prescriptions remedied |

| A.03 | Associated with non-compliances that can be quickly resolved, such as documentary corrections or minor operational adjustments. | Short-term prescription (5–15 days) |

| A.04 | Structural or organizational non-compliances requiring more complex interventions and investment (e.g., renovations, equipment replacement). | Long-term prescription (20–30 days) |

| A.05 | Specific risks exist in processing or testing areas, potentially having a significant impact on production continuity. | Laboratory activities suspended |

| A.06 | Presence of unapproved storage areas, often linked to traceability issues and potential contamination risks. | Unauthorized storage |

| A.07 | Formal report of an infraction, with possible legal implications and financial penalties. | Reporting violation |

| A.08 | Degree of administrative flexibility, granting the operator more time to complete corrective actions, often for technical or economic reasons. | Extension requested and granted |

| A.09 | Obligation to officially notify the completion of corrective actions, useful for subsequent verification and formal closure of the non-compliance. | End of work reporting requirement |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rizzo, C.E.; Venuto, R.; Genovese, G.; Squeri, R.; Genovese, C. Assessment of Food Hygiene Non-Compliance and Control Measures: A Three-Year Inspection Analysis in a Local Health Authority in Southern Italy. Foods 2025, 14, 3364. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14193364

Rizzo CE, Venuto R, Genovese G, Squeri R, Genovese C. Assessment of Food Hygiene Non-Compliance and Control Measures: A Three-Year Inspection Analysis in a Local Health Authority in Southern Italy. Foods. 2025; 14(19):3364. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14193364

Chicago/Turabian StyleRizzo, Caterina Elisabetta, Roberto Venuto, Giovanni Genovese, Raffaele Squeri, and Cristina Genovese. 2025. "Assessment of Food Hygiene Non-Compliance and Control Measures: A Three-Year Inspection Analysis in a Local Health Authority in Southern Italy" Foods 14, no. 19: 3364. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14193364

APA StyleRizzo, C. E., Venuto, R., Genovese, G., Squeri, R., & Genovese, C. (2025). Assessment of Food Hygiene Non-Compliance and Control Measures: A Three-Year Inspection Analysis in a Local Health Authority in Southern Italy. Foods, 14(19), 3364. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14193364