Education and Meat Consumption and Reduction: The Mediating Role of Climate Literacy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Education and Pro-Environmental Behaviour

2.2. Climate Literacy as a Mediator

2.3. Literature Gap

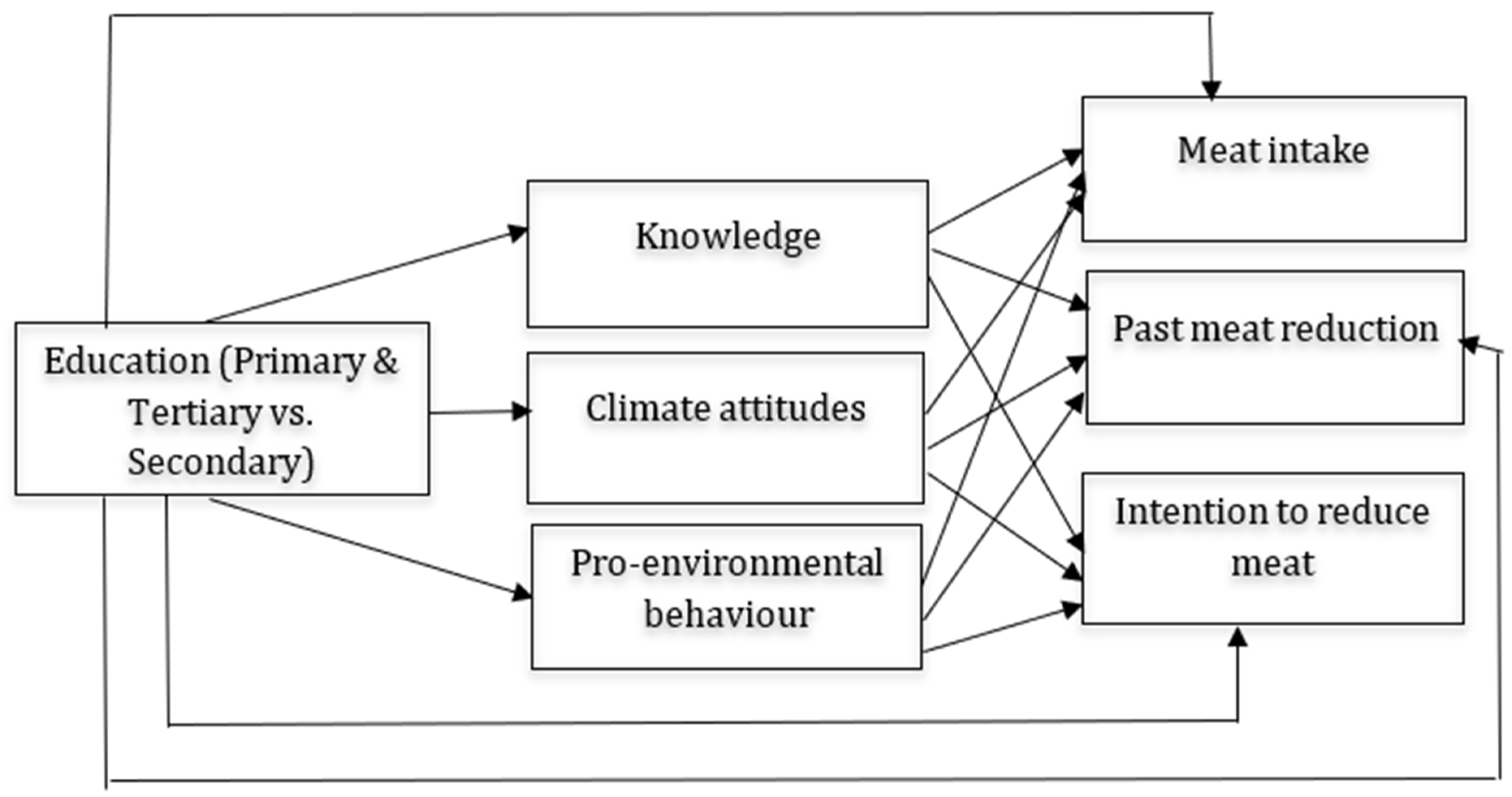

2.4. Study Aim and Hypotheses

3. Method

3.1. Sample

3.2. Measurement

3.2.1. Outcome Variables

3.2.2. Educational Predictor Variables

3.2.3. Climate Literacy

3.3. Analytical Methods

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Bivariate Correlations

4.3. Mediation Analyses

4.3.1. Educational Stage Among School-Enrolled Youth

4.3.2. Educational Track Among High School Students

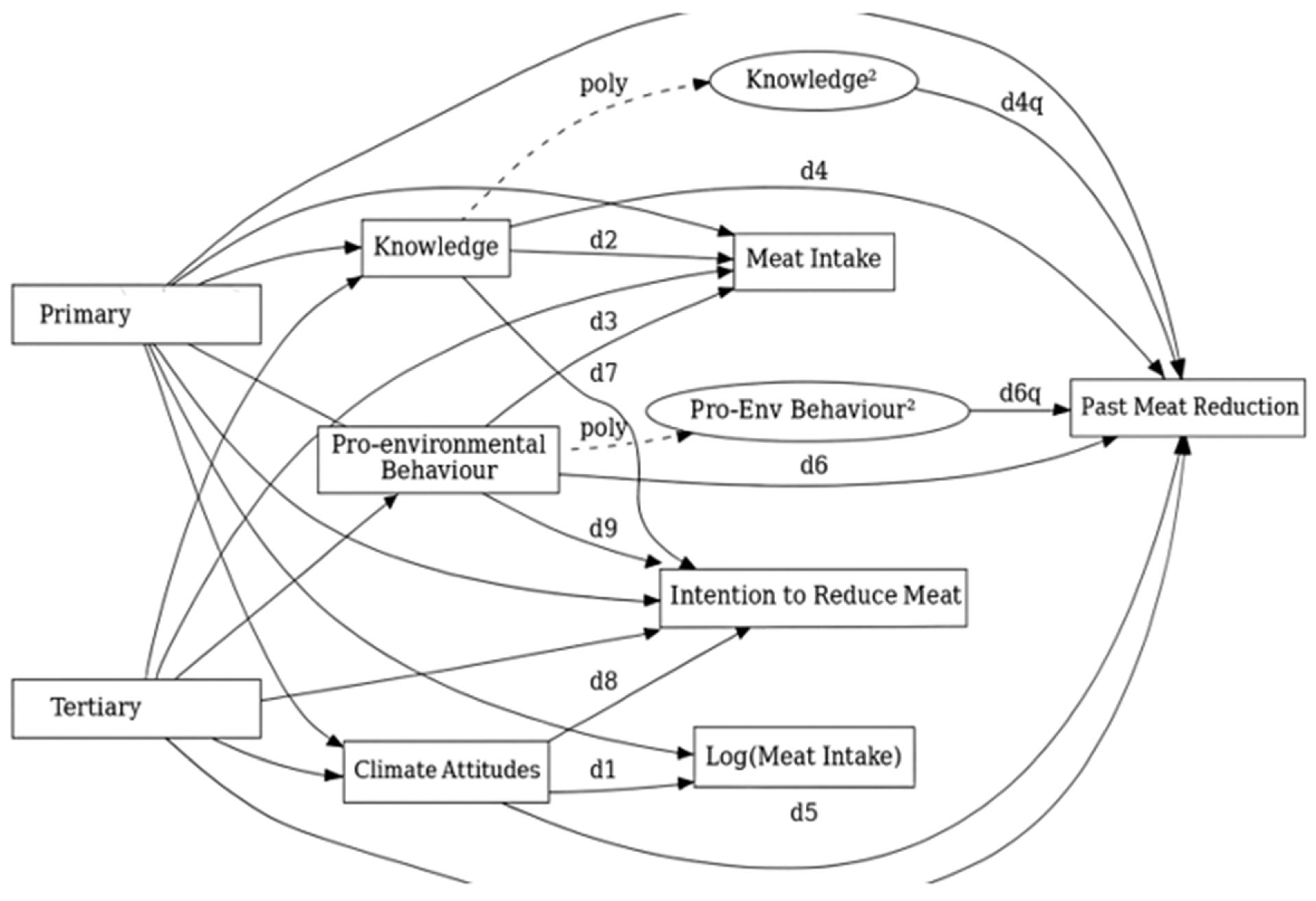

4.3.3. Educational Level Among Adults

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, D.; Zhao, L.; Ma, S.; Shao, S.; Zhang, L. What Influences an Individual’s pro-Environmental Behavior? A Literature Review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Liu, X. Pro-Environmental Behavior Research: Theoretical Progress and Future Directions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, M.; Yu, X.; Ren, H. What Keeps Chinese from Recycling: Accessibility of Recycling Facilities and the Behavior. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 109, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Ueland, S.M.; Olivetti, E. Econometric Modeling of Recycled Copper Supply. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 122, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, L.; Garvill, J.; Nordlund, A.M. Acceptability of Single and Combined Transport Policy Measures: The Importance of Environmental and Policy Specific Beliefs. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2008, 42, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigamonti, L.; Grosso, M.; Møller, J.; Martinez Sanchez, V.; Magnani, S.; Christensen, T.H. Environmental Evaluation of Plastic Waste Management Scenarios. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 85, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xing, P.; Liu, J. Environmental Performance Evaluation of Different Municipal Solid Waste Management Scenarios in China. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 125, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardi, U. A Cross-Country Comparison of the Building Energy Consumptions and Their Trends. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 123, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clune, S.; Crossin, E.; Verghese, K. Systematic Review of Greenhouse Gas Emissions for Different Fresh Food Categories. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 766–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sares-Jäske, L.; Tapanainen, H.; Valsta, L.; Haario, P.; Männistö, S.; Vaalavuo, M. Meat Consumption and Obesity: A Climate-friendly Way to Reduce Health Inequalities. Public Health Chall. 2024, 3, e163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, N.; Marquès, M.; Nadal, M.; Domingo, J.L. Meat Consumption: Which Are the Current Global Risks? A Review of Recent (2010–2020) Evidences. Food Res. Int. 2020, 137, 109341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rust, N.A.; Ridding, L.; Ward, C.; Clark, B.; Kehoe, L.; Dora, M.; Whittingham, M.J.; McGowan, P.; Chaudhary, A.; Reynolds, C.J.; et al. How to Transition to Reduced-Meat Diets That Benefit People and the Planet. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 718, 137208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallström, E.; Carlsson-Kanyama, A.; Börjesson, P. Environmental Impact of Dietary Change: A Systematic Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 91, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schösler, H.; De Boer, J.; Boersema, J.J.; Aiking, H. Meat and Masculinity among Young Chinese, Turkish and Dutch Adults in the Netherlands. Appetite 2015, 89, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allès, B.; Baudry, J.; Méjean, C.; Touvier, M.; Péneau, S.; Hercberg, S.; Kesse-Guyot, E. Comparison of Sociodemographic and Nutritional Characteristics between Self-Reported Vegetarians, Vegans, and Meat-Eaters from the NutriNet-Santé Study. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verain, M.C.D.; Dagevos, H. Comparing Meat Abstainers with Avid Meat Eaters and Committed Meat Reducers. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1016858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusliza, M.Y.; Amirudin, A.; Rahadi, R.A.; Nik Sarah Athirah, N.A.; Ramayah, T.; Muhammad, Z.; Dal Mas, F.; Massaro, M.; Saputra, J.; Mokhlis, S. An Investigation of Pro-Environmental Behaviour and Sustainable Development in Malaysia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Perales, I.; Valero-Gil, J.; Leyva-de La Hiz, D.I.; Rivera-Torres, P.; Garcés-Ayerbe, C. Educating for the Future: How Higher Education in Environmental Management Affects pro-Environmental Behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 128972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Green, R.J. Children’s pro-Environmental Behaviour: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 205, 107524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, E.; Worsley, A. Influences on Meat Consumption in Australia. Appetite 2001, 36, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latvala, T.; Niva, M.; Mäkelä, J.; Pouta, E.; Heikkilä, J.; Kotro, J.; Forsman-Hugg, S. Diversifying Meat Consumption Patterns: Consumers’ Self-Reported Past Behaviour and Intentions for Change. Meat Sci. 2012, 92, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hielkema, M.H.; Lund, T.B. Reducing Meat Consumption in Meat-Loving Denmark: Exploring Willingness, Behavior, Barriers and Drivers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 93, 104257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Berg, S.W.; Van Den Brink, A.C.; Wagemakers, A.; Den Broeder, L. Reducing Meat Consumption: The Influence of Life Course Transitions, Barriers and Enablers, and Effective Strategies According to Young Dutch Adults. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 100, 104623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, A. Does Education Increase Pro-Environmental Behavior? Evidence from Europe. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 116, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chankrajang, T.; Muttarak, R. Green Returns to Education: Does Schooling Contribute to Pro-Environmental Behaviours? Evidence from Thailand. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 131, 434–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirbiš, A.; Korže, V.; Lubej, M. Predictors of Meat Reduction: The Case of Slovenia. Foods 2024, 13, 2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davitt, E.D.; Winham, D.M.; Heer, M.M.; Shelley, M.C.; Knoblauch, S.T. Predictors of Plant-Based Alternatives to Meat Consumption in Midwest University Students. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2021, 53, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borusiak, B.; Szymkowiak, A.; Kucharska, B.; Gálová, J.; Mravcová, A. Predictors of Intention to Reduce Meat Consumption Due to Environmental Reasons—Results from Poland and Slovakia. Meat Sci. 2022, 184, 108674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klink, U.; Mata, J.; Frank, R.; Schüz, B. Socioeconomic Differences in Animal Food Consumption: Education Rather than Income Makes a Difference. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 993379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, J.; Kadel, P.; Frank, R.; Schüz, B. Education- and Income-Related Differences in Processed Meat Consumption across Europe: The Role of Food-Related Attitudes. Appetite 2023, 182, 106417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, W.-L.; Fan, R.; Pan, W.; Ma, X.; Hu, C.; Fu, P.; Su, J. The Role of Climate Literacy in Individual Response to Climate Change: Evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 405, 136874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.; López-Mosquera, N.; Lera-López, F. Improving Pro-Environmental Behaviours in Spain. The Role of Attitudes and Socio-Demographic and Political Factors. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2016, 18, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolenatý, M.; Kroufek, R.; Činčera, J. What Triggers Climate Action: The Impact of a Climate Change Education Program on Students’ Climate Literacy and Their Willingness to Act. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosburger, R.; Richter, A.; Manz, K.; Mensink, G.; Loss, J. Perspectives of Individuals on Reducing Meat Consumption to Mitigate Climate Change: A Scoping Review. Eur. J. Public Health 2023, 33, ckad160.1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellows, A.C.; Onyango, B.; Diamond, A.; Hallman, W.K. Understanding Consumer Interest in Organics: Production Values vs. Purchasing Behavior. J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2008, 6, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundaca, L.; Neij, L.; Worrell, E.; McNeil, M. Evaluating Energy Efficiency Policies with Energy-Economy Models. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2010, 35, 305–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, I.; Missios, P. Recycling and Waste Diversion Effectiveness: Evidence from Canada. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2005, 30, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penny, J.C.; Swift, J.A.; Salter, A.M. “Meat Reducers”: Meat Reduction Strategies and Attitudes towards Meat Alternatives in an Emerging Group. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2015, 74, E313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matek Sarić, M.; Jakšić, K.; Čulin, J.; Guiné, R.P.F. Environmental and Political Determinants of Food Choices: A Preliminary Study in a Croatian Sample. Environments 2020, 7, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, P.M.; Jensen, H.H.; Batres-Marquez, S.P.; Chen, C.-F. Sociodemographic, Knowledge, and Attitudinal Factors Related to Meat Consumption in the United States. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2005, 105, 1266–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiler, T.M.; Egloff, B. Personality and Meat Consumption: The Importance of Differentiating between Type of Meat. Appetite 2018, 130, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehto, E.; Kaartinen, N.E.; Sääksjärvi, K.; Männistö, S.; Jallinoja, P. Vegetarians and Different Types of Meat Eaters among the Finnish Adult Population from 2007 to 2017. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 127, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leve, A.-K.; Michel, H.; Harms, U. Implementing Climate Literacy in Schools—What to Teach Our Teachers? Clim. Change 2023, 176, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Pan, W.; Wen, L.; Pan, W. Can Climate Literacy Decrease the Gap between Pro-Environmental Intention and Behaviour? J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, V. Study of Climate Literacy and Pro-Environmental Behavior amongst Students. Citizsh. Soc. Econ. Educ. 2024, 23, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pothitou, M.; Hanna, R.F.; Chalvatzis, K.J. Environmental Knowledge, pro-Environmental Behaviour and Energy Savings in Households: An Empirical Study. Appl. Energy 2016, 184, 1217–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnek, G.; Kossowska, M.; Szwed, P. Right-Wing Ideology Reduces the Effects of Education on Climate Change Beliefs in More Developed Countries. Nat. Clim. Change 2021, 11, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Aina, Y.A.; Dinis, M.A.P.; Purcell, W.; Nagy, G.J. Climate Change: Why Higher Education Matters? Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-Y.; Won, A.-R.; Chu, H.-E.; Cha, H.-J.; Shin, H.; Kim, C.-J. The Impacts of a Climate Change SSI-STEAM Program on Junior High School Students’ Climate Literacy. Asia-Pac. Sci. Educ. 2021, 7, 96–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agosta Scarel, E.; Cuetos Revuelta, M.J. Estudio Sobre La Importancia de La Alfabetización Climática En La Escuela Secundaria Obligatoria: Un Estudio de Caso. Rev. Eureka. Ensen. Divulg. Cienc. 2023, 20, 3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, R.; Rodrigues, M.J.; Rodrigues, I. Activity Proposals to Improve Children’s Climate Literacy and Environmental Literacy. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubej, M.; Petraš, Ž.; Kirbiš, A. Measuring Climate Knowledge: A Systematic Review of Quantitative Studies. iScience 2025, 28, 111888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austgulen, M.H.; Skuland, S.E.; Schjøll, A.; Alfnes, F. Consumer Readiness to Reduce Meat Consumption for the Purpose of Environmental Sustainability: Insights from Norway. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, G.J.; Schoen, K.; Botta, M. Lifestyle Decisions and Climate Mitigation: Current Action and Behavioural Intent of Youth. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Change 2021, 26, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnaudova, M.; Brunner, T.A.; Götze, F. Examination of Students’ Willingness to Change Behaviour Regarding Meat Consumption. Meat Sci. 2022, 184, 108695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SURS Statistični Urad Republike Slovenije. 2025. Available online: http://www.stat.si/StatWeb/Common/PrikaziDokument.ashx?IdDatoteke=7785 (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- De Waters, J.E.; Andersen, C.; Calderwood, A.; Powers, S.E. Improving Climate Literacy with Project-Based Modules Rich in Educational Rigor and Relevance. J. Geosci. Educ. 2014, 62, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, E.A.; Slate, E.H. Global Validation of Linear Model Assumptions. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2006, 101, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirshenbaum, J.S.; Coury, S.M.; Colich, N.L.; Manber, R.; Gotlib, I.H. Objective and Subjective Sleep Health in Adolescence: Associations with Puberty and Affect. J. Sleep Res. 2023, 32, e13805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichardo, C.M.; Molina, K.M.; Rosas, C.E.; Uriostegui, M.; Sanchez-Johnsen, L. Racial Discrimination and Depressive Symptoms among Latina/o College Students: The Role of Racism-Related Vigilance and Sleep. Race Soc. Probl. 2021, 13, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysko, K.M.; Henry, R.G.; Cree, B.A.C.; Lin, J.; University of California, San Francisco MS-EPIC Team; Caillier, S.; Santaniello, A.; Zhao, C.; Gomez, R.; Bevan, C.; et al. Telomere Length Is Associated with Disability Progression in Multiple Sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 2019, 86, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trompeter, N.; Bussey, K.; Hay, P.; Griffiths, S.; Murray, S.B.; Mond, J.; Lonergan, A.; Pike, K.M.; Mitchison, D. Fear of Negative Evaluation among Eating Disorders: Examining the Association with Weight/Shape Concerns in Adolescence. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2019, 52, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinai, T.; Axelrod, R.; Shimony, T.; Boaz, M.; Kaufman-Shriqui, V. Dietary Patterns among Adolescents Are Associated with Growth, Socioeconomic Features, and Health-Related Behaviors. Foods 2021, 10, 3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Full Sample | Representative Sample of Adults (Weighted) | Population of Slovenia | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | ||

| Gender | Male | 45.8% | 50.0% | 50.0% |

| Female | 54.2% | 50.0% | 50.0% | |

| Status | Active (employed part-time, full-time, etc.) | 25.4% | 47.2% | 55.1% |

| Retired | 9.5% | 32.9% | 29.6% | |

| Other (students) | 65.0% | 19.9% | 15.3% | |

| Education | Primary or less | 2.1% | 18.7% | 19.0% |

| Secondary | 58.1% | 54.1% | 54.0% | |

| Tertiary | 39.5% | 27.2% | 27.0% | |

| Age | 18–34 years old | 26.2% | 21.5% | 22.0% |

| 35–44 years old | 13.4% | 17.3% | 17.0% | |

| 45–54 years old | 19.7% | 17.6% | 18.0% | |

| 55–64 years old | 19.4% | 17.0% | 17.0% | |

| older than 65 years | 21.3% | 26.5% | 26.0% |

| School-Enrolled Youth | High School Students | Adults | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | Groups | ||

| Dimensions | Knowledge ** | 3.27 | 0.65 | 3.37 | 0.63 | 3.41 | 0.55 | a b a |

| Climate attitudes ** | 3.1 | 0.6 | 3.04 | 0.63 | 3.27 | 0.7 | b b a | |

| Pro-environmental behaviour ** | 3.24 | 0.41 | 3.25 | 0.44 | 3.59 | 0.46 | b b a | |

| Sub-dimensions of knowledge | Climate science knowledge * | 2.46 | 0.99 | 2.62 | 0.93 | 2.52 | 0.86 | ab b a |

| Causes and consequences of climate change ** | 3.66 | 0.6 | 3.71 | 0.65 | 3.79 | 0.71 | ab b a | |

| Climate change mitigation * | 4 | 0.63 | 4.02 | 0.65 | 4.08 | 0.67 | ab b a | |

| Sub-dimensions of climate attitudes | Conviction and concern about the climate change ** | 3.14 | 0.68 | 3.12 | 0.71 | 3.28 | 0.76 | b b a |

| Perceived ability to act to reduce global warming (self-efficacy) | 3.46 | 0.73 | 3.45 | 0.76 | 3.5 | 0.8 | a a a | |

| Supporting government policies to reduce global warming ** | 2.7 | 1.01 | 2.53 | 1.04 | 3.04 | 1.07 | b c a | |

| Sub-dimensions of pro-environmental behaviour | Energy saving ** | 3.46 | 0.66 | 3.5 | 0.67 | 3.86 | 0.63 | b b a |

| Mobility | 3.6 | 0.73 | 3.58 | 0.75 | 3.59 | 0.71 | a a a | |

| Waste management ** | 3.09 | 0.52 | 3.09 | 0.57 | 3.36 | 0.58 | b b a | |

| Recycling ** | 3.44 | 0.68 | 3.45 | 0.7 | 4.03 | 0.71 | b b a | |

| Consumer behaviour ** | 3.02 | 0.49 | 3.01 | 0.52 | 3.47 | 0.59 | b b a | |

| Indirect pro-environmental behaviour ** | 2.85 | 0.55 | 2.88 | 0.57 | 3.21 | 0.57 | b b a | |

| Meat consumption and reduction | Meat eating ** | 1.67 | 0.95 | 1.55 | 0.87 | 2.08 | 0.92 | b b a |

| Past meat reduction ** | 3.05 | 1.1 | 2.92 | 1.08 | 3.52 | 0.95 | b b a | |

| Intention to reduce meat ** | 3.09 | 0.89 | 3.04 | 0.91 | 3.32 | 0.77 | b b a | |

| School-Enrolled Youth | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| 1. Educational stage | |||||||

| 2. Knowledge | 0.38 * | ||||||

| 3. Climate attitudes | 0.13 * | 0.35 * | |||||

| 4. Pro-environmental behaviour | 0.20 * | 0.39 * | 0.43* | ||||

| 5. Meat intake | 0.10 * | −0.01 | 0.17 * | 0.14 * | |||

| 6. Past meat reduction | 0.09 * | −0.03 | 0.17 * | 0.11 * | 0.45 * | ||

| 7. Intention to reduce meat | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.11 * | 0.07 * | 0.30 * | 0.44 * | |

| High school students | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| 1. Educational track | |||||||

| 2. Knowledge | 0.44 * | ||||||

| 3. Climate attitudes | 0.28 * | 0.31 * | |||||

| 4. Pro-environmental behaviour | 0.28 * | 0.33 * | 0.48 * | ||||

| 5. Meat intake | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.19 * | 0.17 * | |||

| 6. Past meat reduction | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.23 * | 0.21 * | 0.41 * | ||

| 7. Intention to reduce meat | −0.01 | −0.01 | 0.19 * | 0.21 * | 0.30 * | 0.47 * | |

| Adults | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| 1. Educational level | |||||||

| 2. Knowledge | 0.13 * | ||||||

| 3. Climate attitudes | 0.20 * | 0.48 * | |||||

| 4. Pro-environmental behaviour | 0.27 * | 0.21 * | 0.42 * | ||||

| 5. Meat intake | 0.20 * | −0.04 * | 0.19 * | 0.30 * | |||

| 6. Past meat reduction | 0.16 * | −0.01 | 0.17 * | 0.23 * | 0.48 * | ||

| 7. Intention to reduce meat | 0.09 * | 0.01 | 0.19 * | 0.19 * | 0.28 * | 0.51 * |

| Paths | Estimate | SE | 95% CI [LL, UL] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary educational stage → Knowledge (a1) | −0.395 ** | 0.043 | [−0.480, −0.311] | |

| Primary educational stage → Climate attitudes (a3) | 0.015 | 0.041 | [−0.066, 0.096] | |

| Primary educational stage → Pro-environmental behaviour (a5) | −0.112 ** | 0.03 | [−0.171, −0.052] | |

| Climate attitudes → Meat intake (log) (d1) | 0.007 * | 0.003 | [0.000, 0.013] | |

| Knowledge → Meat intake (d2) | 0.004 | 0.011 | [−0.018, 0.026] | |

| Pro-environmental behaviour → Meat intake (d3) | −0.043 * | 0.017 | [−0.076, −0.010] | |

| Knowledge→ Past meat reduction (d4) | −0.056 | 0.064 | [−0.180, 0.069] | |

| Knowledge (squared) → Past meat reduction (d4q) | 0.06 | 0.044 | [−0.027, 0.147] | |

| Climate attitudes → Past meat reduction (d5) | 0.176 ** | 0.058 | [0.062, 0.290] | |

| Pro-environmental behaviour → Past meat reduction (d6) | 0.048 | 0.079 | [−0.107, 0.203] | |

| Pro-environmental behaviour (squared) → Past meat reduction (d6q) | −0.100 | 0.106 | [−0.308, 0.107] | |

| Knowledge → Intention to reduce meat (d7) | −0.183 ** | 0.057 | [−0.294, −0.072] | |

| Climate attitudes → Intention to reduce meat (d8) | 0.178 ** | 0.052 | [0.076, 0.280] | |

| Pro-environmental behaviour → Intention to reduce meat (d9) | 0.124 | 0.072 | [−0.018, 0.266] | |

| Primary educational stage → Meat intake (log) (c1) | 0.029 | 0.020 | [−0.010, 0.069] | |

| Primary educational stage → Meat intake (c3) | 0.083 | 0.064 | [−0.042, 0.207] | |

| Primary educational stage → Past meat reduction (c5) | 0.053 | 0.081 | [−0.106, 0.212] | |

| Primary educational stage → Intention to reduce meat (c7) | −0.009 | 0.069 | [−0.144, 0.126] | |

| Indirect effects | On Meat intake via Climate attitudes | 0.000 | 0.000 | [−0.000, 0.001] |

| On Meat intake via Knowledge | −0.002 | 0.004 | [−0.010, 0.007] | |

| On Meat intake via Pro-environmental behaviour | 0.005 * | 0.002 | [0.000, 0.009] | |

| On Past meat reduction via Knowledge (poly) | −0.002 | 0.035 | [−0.071, 0.068] | |

| On Past meat reduction via Climate attitudes | 0.003 | 0.007 | [−0.012, 0.017] | |

| On Past meat reduction via Pro-environmental behaviour (poly) | 0.006 | 0.016 | [−0.026, 0.038] | |

| On Intention to reduce meat via Knowledge | 0.072 ** | 0.024 | [0.026, 0.119] | |

| On Intention to reduce meat via Climate attitudes | 0.003 | 0.007 | [−0.012, 0.017] | |

| On Intention to reduce meat via Pro-environmental behaviour | −0.014 | 0.009 | [−0.031, 0.004] | |

| Total effects | Meat intake | 0.033 | 0.021 | [−0.008, 0.010] |

| Past meat reduction | 0.060 | 0.082 | [−0.101, 0.220] | |

| Intention to reduce meat | 0.052 | 0.067 | [−0.079, 0.183] |

| Paths | Estimate | SE | 95% CI [LL, UL] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tertiary educational stage → Knowledge (a2) | 0.159 ** | 0.047 | [0.067, 0.252] | |

| Tertiary educational stage → Climate attitudes (a4) | 0.216 ** | 0.047 | [0.124, 0.309] | |

| Tertiary educational stage → Pro-environmental behaviour (a6) | 0.115 ** | 0.029 | [0.057, 0.172] | |

| Climate attitudes → Meat intake (log) (d1) | 0.007 * | 0.003 | [0.000, 0.013] | |

| Knowledge → Meat intake (d2) | 0.004 | 0.011 | [−0.018, 0.026] | |

| Pro-environmental behaviour → Meat intake (d3) | −0.043 * | 0.017 | [−0.076, −0.010] | |

| Knowledge → Past meat reduction (d4) | −0.056 | 0.064 | [−0.180, 0.069] | |

| Knowledge (squared) → Past meat reduction (d4q) | 0.06 | 0.044 | [−0.027, 0.147] | |

| Climate attitudes → Past meat reduction (d5) | 0.176 ** | 0.058 | [0.062, 0.290] | |

| Pro-environmental behaviour → Past meat reduction (d6) | 0.048 | 0.079 | [−0.107, 0.203] | |

| Pro-environmental behaviour (squared) → Past meat reduction (d6q) | −0.100 | 0.106 | [−0.308, 0.107] | |

| Knowledge → Intention to reduce meat (d7) | −0.183 ** | 0.057 | [−0.294, −0.072] | |

| Climate attitudes → Intention to reduce meat (d8) | 0.178 ** | 0.052 | [0.076, 0.280] | |

| Pro-environmental behaviour → Intention to reduce meat (d9) | 0.124 | 0.072 | [−0.018, 0.266] | |

| Tertiary educational stage → Meat intake (log) (c2) | 0.111 ** | 0.023 | [0.066, 0.157] | |

| Tertiary educational stage → Meat intake (c4) | 0.343 ** | 0.075 | [0.197, 0.490] | |

| Tertiary educational stage → Past meat reduction (c6) | 0.317 ** | 0.08 | [0.159, 0.474] | |

| Tertiary educational stage → Intention to reduce meat (c8) | 0.116 | 0.059 | [−0.001, 0.232] | |

| Indirect effects | On Meat intake via Climate attitudes | 0.001 ** | 0.001 | [0.000, 0.003] |

| On Meat intake via Knowledge | 0.001 | 0.002 | [−0.003, 0.004] | |

| On Meat intake via Pro-environmental behaviour | −0.005 * | 0.002 | [−0.010, −0.000] | |

| On Past meat reduction via Knowledge (poly) | 0.001 | 0.014 | [−0.027, 0.029] | |

| On Past meat reduction via Climate attitudes | 0.038 * | 0.015 | [0.009, 0.068] | |

| On Past meat reduction via Pro-environmental behaviour (poly) | −0.006 | 0.017 | [−0.039, 0.027] | |

| On Intention to reduce meat via Knowledge | −0.029 * | 0.012 | [−0.053, −0.006] | |

| On Intention to reduce meat via Climate attitudes | 0.039 ** | 0.014 | [0.010, 0.067] | |

| On Intention to reduce meat via Pro-environmental behaviour | 0.014 | 0.009 | [−0.004, 0.032] | |

| Total effects | Meat intake | 0.108 ** | 0.023 | [0.062, 0.154] |

| Past meat reduction | 0.350 ** | 0.081 | [0.191, 0.509] | |

| Intention to reduce meat | 0.139 * | 0.061 | [0.019, 0.259] |

| Paths | Estimate | SE | 95% CI [LL, UL] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vocational school → Knowledge (a1) | −0.431 ** | 0.076 | [−0.580, −0.282] | |

| Vocational school → Climate attitudes (a3) | −0.080 | 0.072 | [−0.221, 0.061] | |

| Vocational school → Pro-environmental behaviour (a5) | −0.122 * | 0.048 | [−0.216, −0.028] | |

| Knowledge → Meat intake (b1) | −0.051 | 0.086 | [−0.219, 0.117] | |

| Climate attitudes → Meat intake (b2) | 0.112 | 0.071 | [−0.027, 0.251] | |

| Pro-environmental behaviour → Meat intake (b3) | 0.143 | 0.130 | [−0.112, 0.398] | |

| Knowledge → Past meat reduction (b4) | −0.045 | 0.112 | [−0.265, 0.175] | |

| Climate attitudes → Past meat reduction (b5) | 0.290 ** | 0.104 | [0.086, 0.494] | |

| Pro-environmental behaviour → Past meat reduction (b6) | 0.325 * | 0.147 | [0.037, 0.613] | |

| Knowledge → Intention to reduce meat (b7) | −0.161 | 0.083 | [−0.324, 0.002] | |

| Climate attitudes → Intention to reduce meat (b8) | 0.246 ** | 0.093 | [0.064, 0.428] | |

| Pro-environmental behaviour → Intention to reduce meat (b9) | 0.348 ** | 0.122 | [0.109, 0.587] | |

| Vocational school → Meat intake (c1) | 0.145 | 0.114 | [−0.078, 0.368] | |

| Vocational school → Past meat reduction (c3) | 0.429 ** | 0.139 | [0.156, 0.702] | |

| Vocational school → Intention to reduce meat (c5) | 0.339 ** | 0.124 | [0.096, 0.582] | |

| Indirect effects | On Meat intake via Knowledge | 0.022 | 0.037 | [−0.051, 0.095] |

| On Past meat reduction via Knowledge | 0.020 | 0.049 | [−0.076, 0.116] | |

| On Intention to reduce meat via Knowledge | 0.069 | 0.038 | [−0.005, 0.143] | |

| On Meat intake via Climate attitudes | −0.009 | 0.010 | [−0.029, 0.011] | |

| On Past meat reduction via Climate attitudes | −0.023 | 0.022 | [−0.066, 0.020] | |

| On intention to reduce meat via Climate attitudes | −0.020 | 0.019 | [−0.057, 0.017] | |

| On Meat intake via Pro-environmental behaviour | −0.017 | 0.017 | [−0.050, 0.016] | |

| On Past meat reduction via Pro-environmental behaviour | −0.040 | 0.023 | [−0.085, 0.005] | |

| On Intention to reduce meat via Pro-environmental behaviour | −0.043 | 0.023 | [−0.088, 0.002] | |

| Total effects | Meat intake | 0.141 | 0.113 | [−0.080, 0.362] |

| Past meat reduction | 0.386 ** | 0.142 | [0.108, 0.664] | |

| Intention to reduce meat | 0.347 ** | 0.127 | [0.098, 0.596] |

| Paths | Estimate | SE | 95% CI [LL, UL] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General school → Knowledge (a2) | 0.275 ** | 0.06 | [0.157, 0.393] | |

| General school → Climate attitudes (a4) | 0.366 ** | 0.072 | [0.225, 0.507] | |

| General school → Pro-environmental behaviour (a6) | 0.201 ** | 0.052 | [0.099, 0.303] | |

| Knowledge → Meat intake (b1) | −0.051 | 0.086 | [−0.219, 0.117] | |

| Climate attitudes → Meat intake (b2) | 0.112 | 0.071 | [−0.027, 0.251] | |

| Pro-environmental behaviour → Meat intake (b3) | 0.143 | 0.13 | [−0.112, 0.398] | |

| Knowledge → Past meat reduction (b4) | −0.045 | 0.112 | [−0.265, 0.175] | |

| Climate attitudes → Past meat reduction (b5) | 0.290 ** | 0.104 | [0.086, 0.494] | |

| Pro-environmental behaviour → Past meat reduction (b6) | 0.325 * | 0.147 | [0.037, 0.613] | |

| Knowledge → Intention to reduce meat (b7) | −0.161 | 0.083 | [−0.324, 0.002] | |

| Climate attitudes → Intention to reduce meat (b8) | 0.246 ** | 0.093 | [0.064, 0.428] | |

| Pro-environmental behaviour → Intention to reduce meat (b9) | 0.348 ** | 0.122 | [0.109, 0.587] | |

| General school → Meat intake (c2) | 0.125 | 0.104 | [−0.079, 0.329] | |

| General school → Past meat reduction (c4) | 0.288 * | 0.129 | [0.035, 0.541] | |

| General school → Intention to reduce meat (c6) | 0.129 | 0.099 | [−0.065, 0.323] | |

| Indirect effects | ||||

| On Meat intake via Knowledge | −0.014 | 0.024 | [−0.061, 0.033] | |

| On Past meat reduction via Knowledge | −0.012 | 0.031 | [−0.073, 0.049] | |

| On Intention to reduce meat via Knowledge | −0.044 | 0.025 | [−0.093, 0.005] | |

| On Meat intake via Climate attitudes | 0.041 | 0.027 | [−0.012, 0.094] | |

| On Past meat reduction via Climate attitudes | 0.106 * | 0.044 | [0.020, 0.192] | |

| On intention to reduce meat via Climate attitudes | 0.090 * | 0.039 | [0.014, 0.166] | |

| On Meat intake via Pro-environmental behaviour | 0.029 | 0.028 | [−0.026, 0.084] | |

| On Past meat reduction via Pro-environmental behaviour | 0.065 | 0.036 | [−0.005, 0.135] | |

| On Intention to reduce meat via Pro-environmental behaviour | 0.070 * | 0.03 | [0.011, 0.129] | |

| Total effects | Meat intake | 0.181 | 0.096 | [−0.007, 0.369] |

| Past meat reduction | 0.447 *** | 0.116 | [0.220, 0.674] | |

| Intention to reduce meat | 0.245 ** | 0.09 | [0.068, 0.422] |

| Paths | Estimate | SE | 95% CI [LL, UL] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary educational level → Knowledge (a1) | −0.047 | 0.056 | [−0.156, 0.062] | |

| Primary educational level → Climate attitudes (a3) | −0.284 ** | 0.06 | [−0.401, −0.167] | |

| Primary educational level → Pro-environmental behaviour (a5) | −0.347 ** | 0.041 | [−0.428, −0.266] | |

| Knowledge → Meat intake (b1) | −0.378 ** | 0.082 | [−0.540, −0.217] | |

| Climate attitudes → Meat intake (b2) | 0.195 ** | 0.057 | [0.084, 0.306] | |

| Pro-environmental behaviour → Meat intake (b3) | 0.384 ** | 0.079 | [0.230, 0.538] | |

| Knowledge → Past meat reduction (b4) | −0.248 ** | 0.073 | [−0.391, −0.104] | |

| Climate attitudes → Past meat reduction (b5) | 0.201 ** | 0.054 | [0.096, 0.307] | |

| Pro-environmental behaviour → Past meat reduction (b6) | 0.353 ** | 0.078 | [0.201, 0.505] | |

| Knowledge → Intention to reduce meat (b7) | −0.124 * | 0.056 | [−0.233, −0.015] | |

| Climate attitudes → Intention to reduce meat (b8) | 0.178 ** | 0.045 | [0.089, 0.267] | |

| Pro-environmental behaviour → Intention to reduce meat (b9) | 0.258 ** | 0.064 | [0.133, 0.383] | |

| Primary educational level → Meat intake (c1) | −0.127 | 0.083 | [−0.290, 0.035] | |

| Primary educational level → Past meat reduction (c3) | −0.446 ** | 0.097 | [−0.636, −0.256] | |

| Primary educational level → Intention to reduce meat (c5) | −0.286 ** | 0.079 | [−0.441, −0.130] | |

| Indirect effects | On Meat intake via Knowledge | 0.018 | 0.022 | [−0.026, 0.061] |

| On Past meat reduction via Knowledge | 0.012 | 0.015 | [−0.017, 0.041] | |

| On Intention to reduce meat via Knowledge | 0.006 | 0.007 | [−0.008, 0.020] | |

| On Meat intake via Climate attitudes | −0.055 ** | 0.02 | [−0.095, −0.016] | |

| On Past meat reduction via Climate attitudes | −0.057 ** | 0.02 | [−0.096, −0.019] | |

| On intention to reduce meat via Climate attitudes | −0.051 ** | 0.017 | [−0.084, −0.017] | |

| On Meat intake via Pro-environmental behaviour | −0.133 ** | 0.029 | [−0.191, −0.076] | |

| On Past meat reduction via Pro-environmental behaviour | −0.122 ** | 0.029 | [−0.180, −0.065] | |

| On Intention to reduce meat via Pro-environmental behaviour | −0.090 ** | 0.025 | [−0.138, −0.041] | |

| Total effects | Meat intake | −0.298 ** | 0.088 | [−0.470, −0.127] |

| Past meat reduction | −0.614 ** | 0.101 | [−0.813, −0.415] | |

| Intention to reduce meat | −0.420 ** | 0.085 | [−0.586, −0.254] |

| Paths | Estimate | SE | 95% CI [LL, UL] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tertiary educational level → Knowledge (a2) | 0.169 ** | 0.039 | [0.093, 0.245] | |

| Tertiary educational level → Climate attitudes (a4) | 0.130 * | 0.056 | [0.021, 0.239] | |

| Tertiary educational level → Pro-environmental behaviour (a6) | 0.04 | 0.033 | [−0.024, 0.104] | |

| Knowledge → Meat intake (b1) | −0.378 ** | 0.082 | [−0.540, −0.217] | |

| Climate attitudes → Meat intake (b2) | 0.195 ** | 0.057 | [0.084, 0.306] | |

| Pro-environmental behaviour → Meat intake (b3) | 0.384 ** | 0.079 | [0.230, 0.538] | |

| Knowledge → Past meat reduction (b4) | −0.248 ** | 0.073 | [−0.391, −0.104] | |

| Climate attitudes → Past meat reduction (b5) | 0.201 ** | 0.054 | [0.096, 0.307] | |

| Pro-environmental behaviour → Past meat reduction (b6) | 0.353 ** | 0.078 | [0.201, 0.505] | |

| Knowledge → Intention to reduce meat (b7) | −0.124 * | 0.056 | [−0.233, −0.015] | |

| Climate attitudes → Intention to reduce meat (b8) | 0.178 ** | 0.045 | [0.089, 0.267] | |

| Pro-environmental behaviour → Intention to reduce meat (b9) | 0.258 ** | 0.064 | [0.133, 0.383] | |

| Tertiary educational level → Meat intake (c2) | 0.167 ** | 0.061 | [0.048, 0.286] | |

| Tertiary educational level → Past meat reduction (c4) | −0.041 | 0.059 | [−0.157, 0.075] | |

| Tertiary educational level → Intention to reduce meat (c6) | −0.094 | 0.051 | [−0.194, 0.006] | |

| Indirect effects | On Meat intake via Knowledge | −0.064 ** | 0.02 | [−0.103, −0.025] |

| On Past meat reduction via Knowledge | −0.042 ** | 0.015 | [−0.072, −0.012] | |

| On Intention to reduce meat via Knowledge | −0.021 * | 0.011 | [−0.042, −0.000] | |

| On Meat intake via Climate attitudes | 0.025 * | 0.013 | [0.001, 0.050] | |

| On Past meat reduction via Climate attitudes | 0.026 * | 0.013 | [−0.000, 0.052] | |

| On intention to reduce meat via Climate attitudes | 0.023 * | 0.012 | [0.000, 0.046] | |

| On Meat intake via Pro-environmental behaviour | 0.015 | 0.013 | [−0.010, 0.041] | |

| On Past meat reduction via Pro-environmental behaviour | 0.014 | 0.012 | [−0.009, 0.038] | |

| On Intention to reduce meat via Pro-environmental behaviour | 0.01 | 0.009 | [−0.007, 0.028] | |

| Total effects | Meat intake | 0.144 * | 0.063 | [0.020, 0.267] |

| Past meat reduction | −0.043 | 0.06 | [−0.161, 0.075] | |

| Intention to reduce meat | −0.082 | 0.052 | [−0.183, 0.019] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kirbiš, A.; Branilović, S. Education and Meat Consumption and Reduction: The Mediating Role of Climate Literacy. Foods 2025, 14, 3333. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14193333

Kirbiš A, Branilović S. Education and Meat Consumption and Reduction: The Mediating Role of Climate Literacy. Foods. 2025; 14(19):3333. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14193333

Chicago/Turabian StyleKirbiš, Andrej, and Stefani Branilović. 2025. "Education and Meat Consumption and Reduction: The Mediating Role of Climate Literacy" Foods 14, no. 19: 3333. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14193333

APA StyleKirbiš, A., & Branilović, S. (2025). Education and Meat Consumption and Reduction: The Mediating Role of Climate Literacy. Foods, 14(19), 3333. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14193333