Chinese and Korean Consumers’ Preferences for Oolong and Black Oolong Teas

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

2.2. Consumer Participants

2.3. Consumer Tests

2.3.1. Questionnaire

2.3.2. Test Process

2.3.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Composition Effect Test

3.2. Consumer Preferences for Oolong and Black Oolong Teas

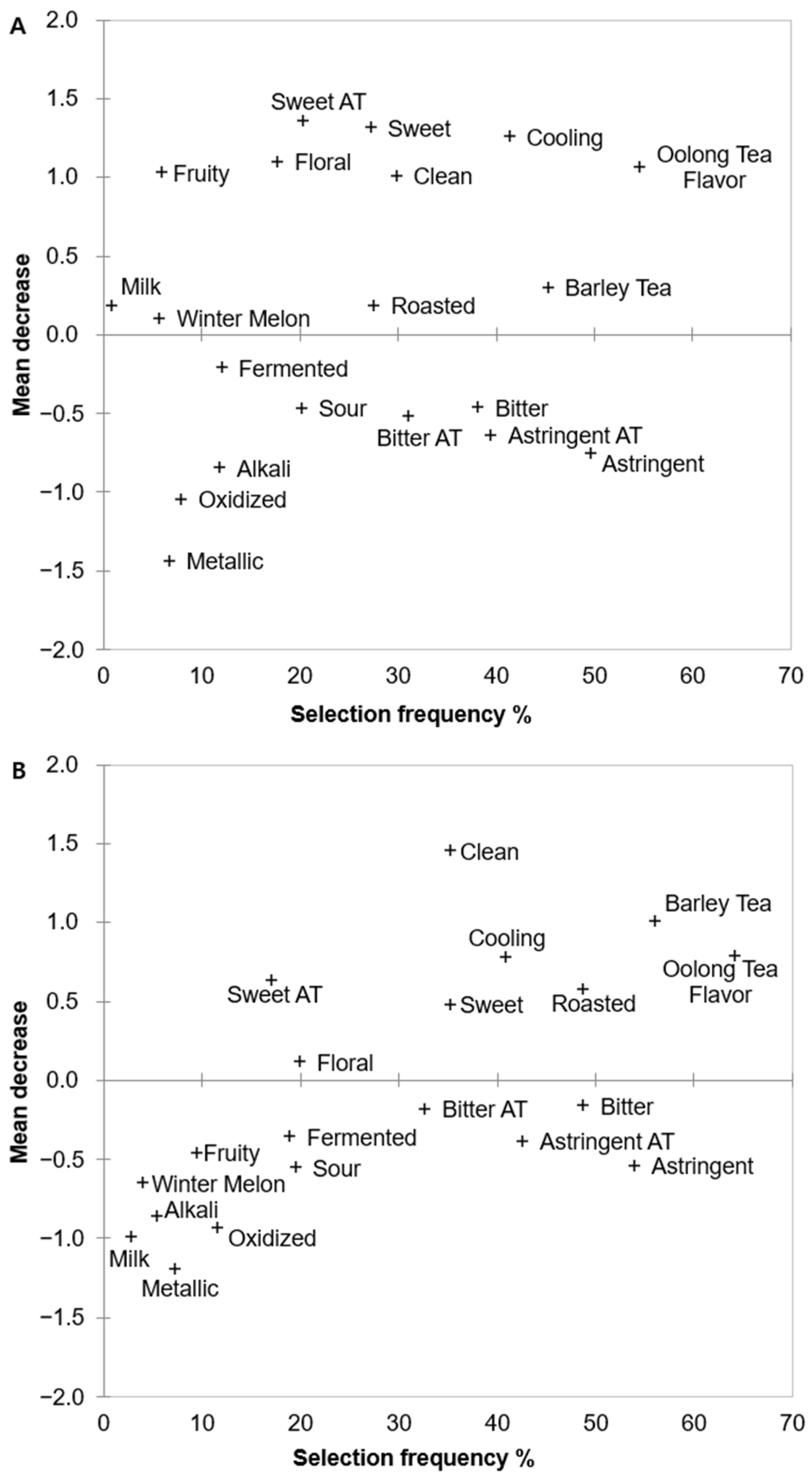

3.3. Characteristics Affecting Oolong and Black Oolong Tea Liking

3.4. Sensory Characteristics of Oolong and Black Oolong Teas

3.4.1. Intensity Rating

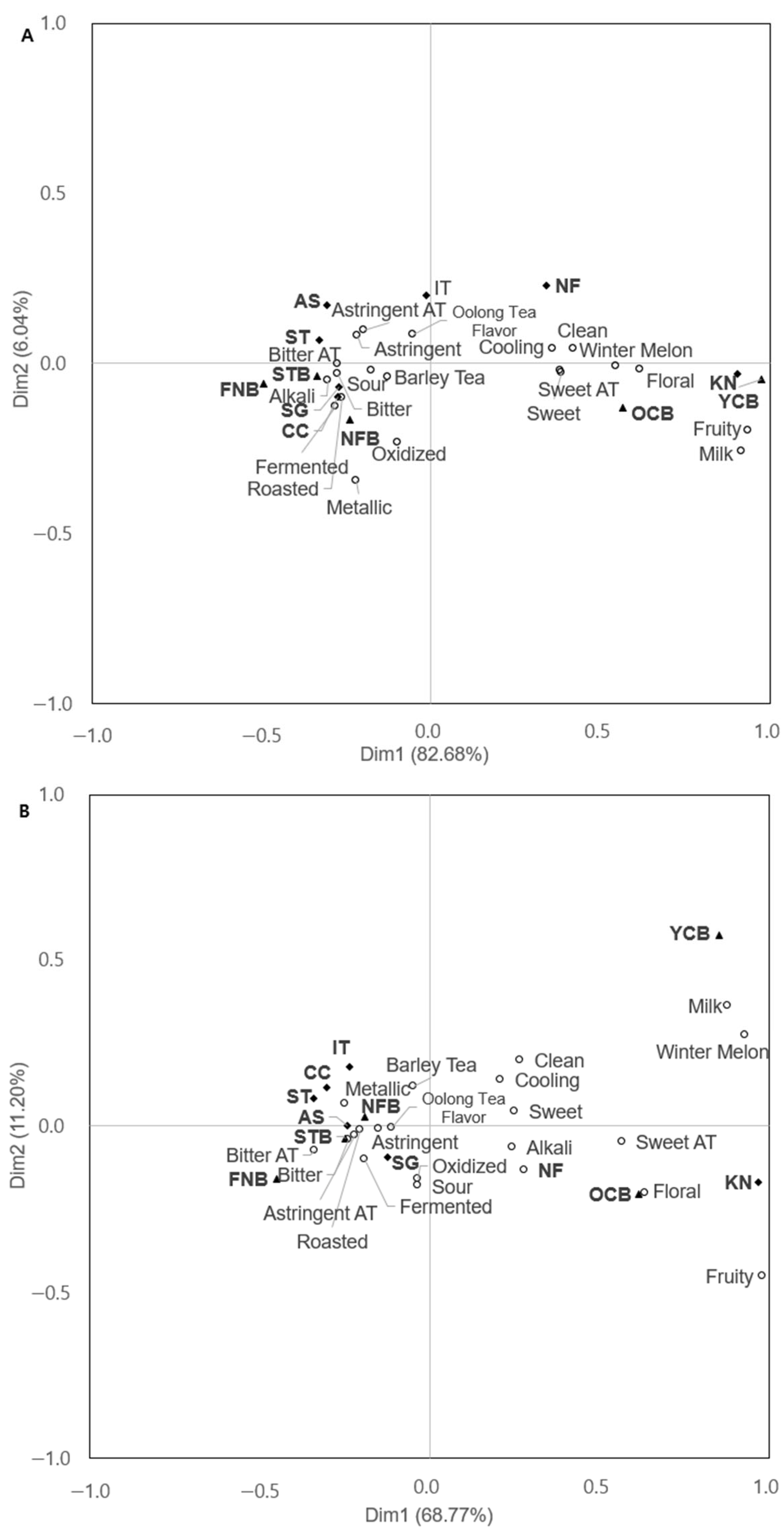

3.4.2. Correspondence Analysis (CA)

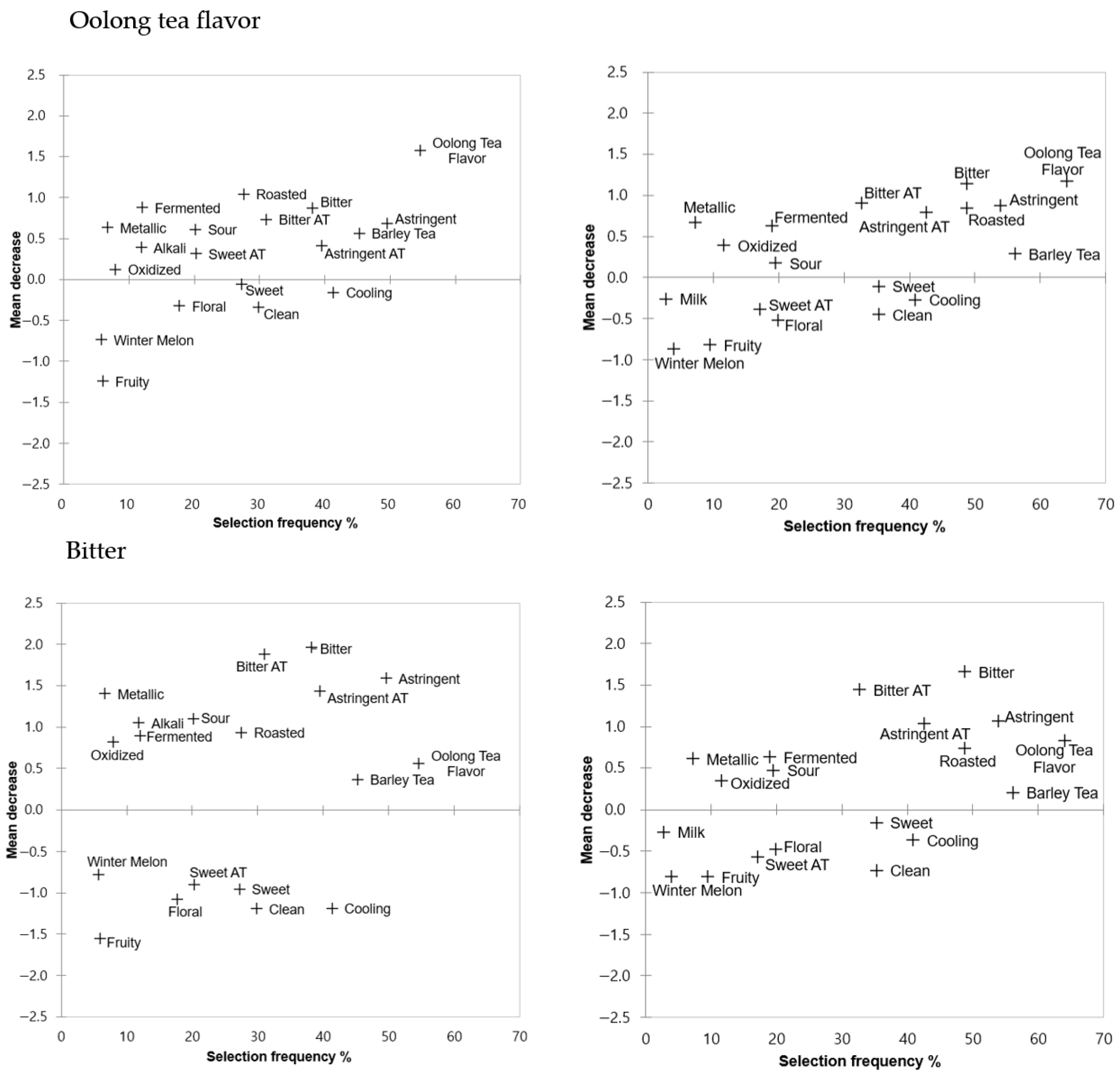

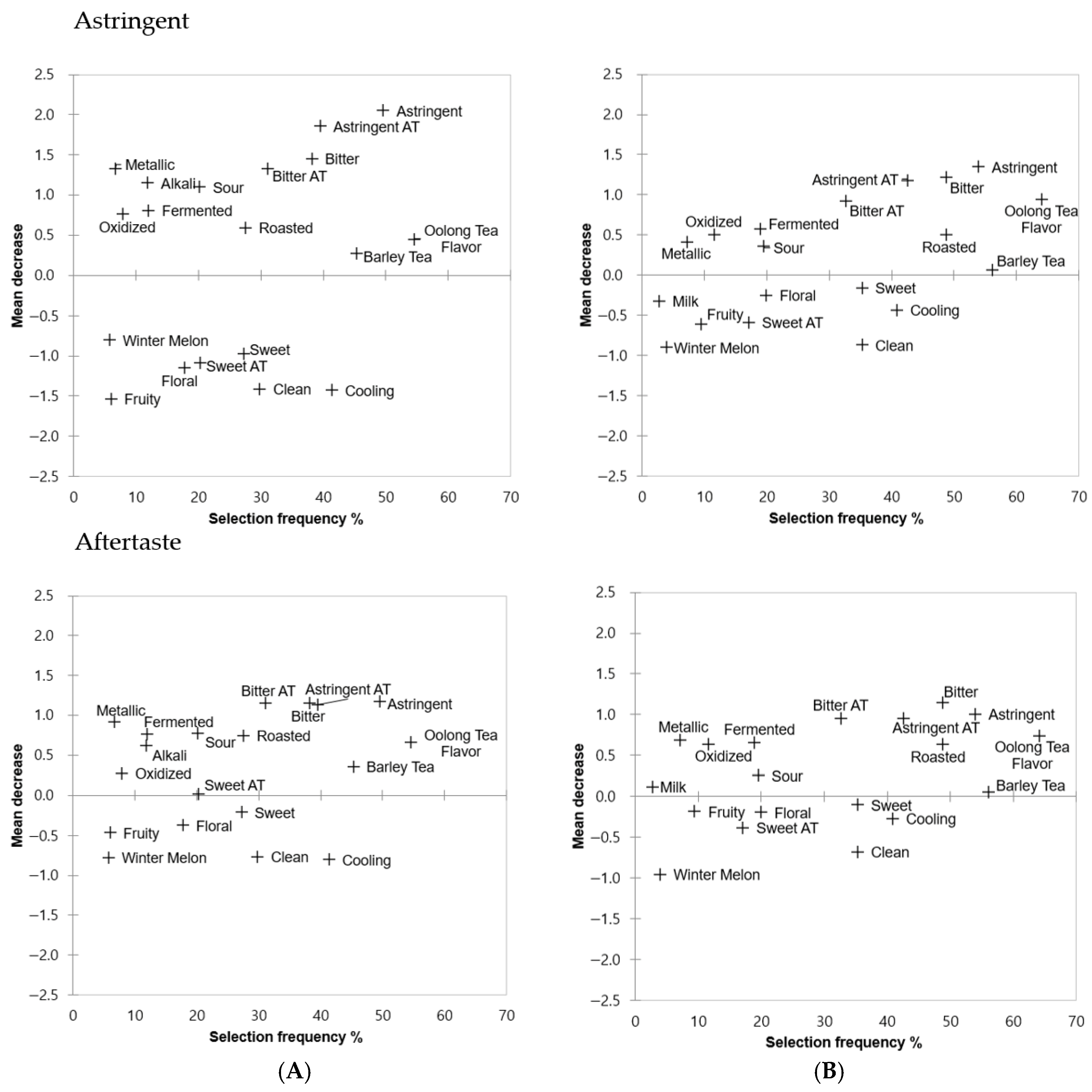

3.4.3. Perception Differences Determined Using CATA and Intensity Data

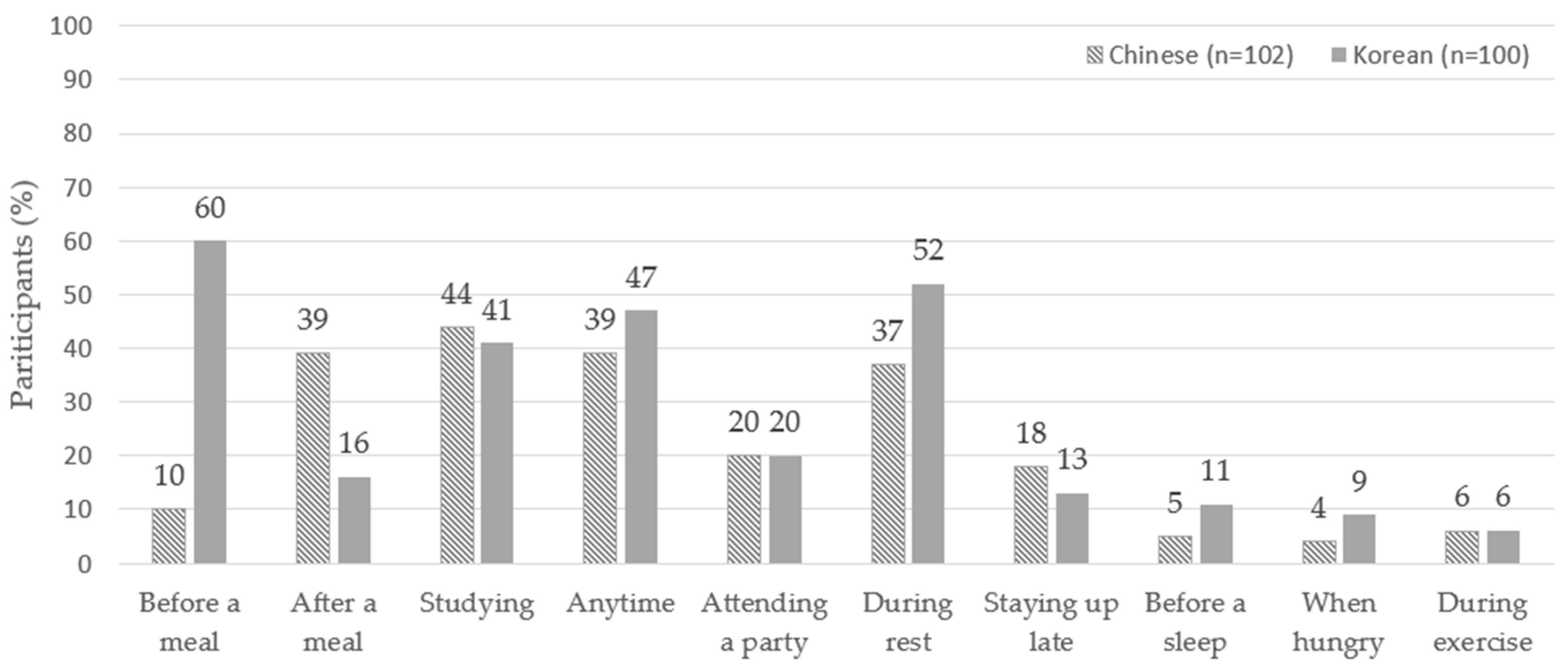

3.5. Consumption Habits

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Y.L.; Duan, J.; Jiang, Y.M.; Shi, J.; Peng, L.; Xue, S.J.; Kakuda, Y. Production, quality, and biological effects of oolong tea (Camellia sinensis). Food Rev. Int. 2010, 27, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, E.C. The tale of tea: A comprehensive history of tea from prehistoric times to the present day. Food Cult. Soc. 2020, 23, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.H.; Li, N.; Zhu, H.T.; Wang, D.; Yang, C.R.; Zhang, Y.J. Plant resources, chemical constituents, and bioactivities of tea plants from the genus Camellia section Thea. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 5318–5349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forward. China Tea Planting and Processing Industry Market Research and Investment Forecast Report (2024–2029). Available online: https://bg.qianzhan.com/report/detail/00477f5796bf4274.html (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Xia, Q.; Donzé, P.Y. Making Japanese tea a big business: The transformation of ITO EN since the 1960s. J. Jpn. Bus. Co. Hist. 2022, 7, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdiana, W. Kajian Bentukan fisik kemasan minuman teh siap Saji. J. Soc. Hum. 2014, 8, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koca, I.; Bostanci, S. Production, composition, and health effects of Oolong tea. Turk. J. Agric. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 2, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Han, Y.J. A Study on Integrated Lifestyle Brand Design of Korean Tea Culture. Ph.D. Thesis, Seoul National University Graduate School, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2017. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10371/128958 (accessed on 1 September 2025).[Green Version]

- Lee, J.; Chambers, D.H. A lexicon for flavor descriptive analysis of green tea. J. Sens. Stud. 2007, 22, 256–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, J.; Aryal, J.; Guidry, L.; Adhikari, A.; Chen, Y.; Sriwattana, S.; Prinyawiwatkul, W. Tea quality: An overview of the analytical methods and sensory analyses used in the most recent studies. Foods 2024, 13, 3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.; Sim, Y.; Heo, S.; Heo, E.; Kim, G.; An, J.; Lee, J. Consumers’ preference and perceived sensory characteristics of oolong tea. Korean J. Food Cook. Sci. 2024, 40, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawless, H.T.; Heymann, H. Sensory Evaluation of Food: Principles and Practices, 2nd ed.; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2010; p. 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, J.; Drabek, R.; Goldman, A. Hedonic contrast effects in multi-product food evaluations differing in complexity. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 63, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahne, J.; Zellner, D.A. The great is the enemy of the good: Hedonic contrast in a coursed meal. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 45, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schouteten, J.J.; De Steur, H.; Sas, B.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Gellynck, X. The effect of the research setting on the emotional and sensory profiling under blind, expected, and informed conditions: A study on premium and private label yogurt products. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weaver, M.R.; Brittin, H.C. Food preferences of men and women by sensory evaluation versus questionnaire. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2001, 29, 288–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Lee, J. The effect of extrinsic cues on consumer perception: A study using milk tea products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 71, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, N.J.N.; Huang, Y.J. The effect of membrane-processed water on sensory properties of Oolong tea drinks. Food Qual. Prefer. 2000, 11, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, J.H.; Choi, Y.K.; Chun, S.S. A Lexicon for descriptive sensory evaluation of blended tea. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2018, 23, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diomede, L.; Salmona, M. The Soothing Effect of Menthol, Eucalyptol and High-Intensity Cooling Agents. Int. J. Nutrafoods Funct. Foods Nov. Foods 2017, 16, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Yang, J.; Choi, K.; Kim, J.; Adhikari, K.; Lee, J. Chemical analysis of commercial white wines and its relationship with consumer acceptability. Foods 2022, 11, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Lee, J. Consumer perception of red wine by the degree of familiarity using consumer-based methodology. Foods 2021, 10, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preece, D.A. Latin squares as experimental designs. In Annals of Discrete Mathematics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1991; Volume 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton, G.J.G. Fisher’s exact test. J. R. Stat. Soc. A 1992, 155, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smilde, A.K.; Kiers, H.A.; Bijlsma, S.; Rubingh, C.M.; Van Erk, M.J. Matrix correlations for high-dimensional data: The modified RV-coefficient. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z. Sensorial place-making in ethnic minority areas: The consumption of forest Puer tea in contemporary China. Asia Pac. J. Anthropol. 2018, 19, 316–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, K.O. Sensory characteristics and consumer acceptability of various green teas. Food Sci. Bio. 2009, 17, 349–356. Available online: https://koreascience.kr/article/JAKO200833338360437.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Kim, Y.K.; Jombart, L.; Valentin, D.; Kim, K.O. Familiarity and liking playing a role on the perception of trained panelists: A cross-cultural study on teas. Food Res. Int. 2015, 71, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Axten, L.G.; Wohlers, M.W.; Sun-Waterhouse, D. Polyphenol-rich beverages: Insights from sensory and consumer science. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2009, 89, 2356–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Chambers, E.; Chambers, D.H.; Chun, S.S.; Oupadissakoon, C.; Johnson, D.E. Consumer acceptance for green tea by consumers in the United States, Korea and Thailand. J. Sens. Stud. 2010, 25, 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, P.; Escoufier, Y. A unifying tool for linear multivariate statistical methods: The RV-coefficient. J. R. Stat. Soc. C 1976, 25, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.; Hyun, T.; Choi, M. Perception and preference of Korean traditional foods by elementary School Students in Chungbuk Province—Tradition Holiday Food, Rice Cake, Non-Alcoholic Beverages. J. Korean Soc. Food Cult. 2002, 17, 399–410. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N. A comparison of Chinese and British tea culture. Asian Cult. Hist. 2011, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chan, E.Y. Cross-cultural consumer behavior. In Consumer Behavior in Practice: Strategic Insights for the Modern Marketer; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, S.; Hossen, M.S.B.; Zim, S.K.; El Hebabi, I. Cultural dynamics and consumer behavior: An in-depth analysis of Chinese preferences for Western imported products. GSC Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 20, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacalone, D.; Frøst, M.B.; Bredie, W.L.P.; Pineau, B.; Hunter, D.C.; Paisley, A.G.; Beresford, M.K.; Jaeger, S.R. Situational appropriateness of beer is influenced by product familiarity. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 39, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boachie-Mensah, F.O.; Boohene, R. A review of cross-cultural variations in consumer behavior and marketing strategy. Int. Bus. Manag. 2012, 5, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Chambers, D.H. Descriptive analysis and US consumer acceptability of 6 green tea samples from China, Japan, and Korea. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, S141–S147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.E.; Lee, J. Consumer perception and liking, and sensory characteristics of blended teas. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 29, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Zhang, G.; Olayemi Aluko, O.; Mo, Z.; Mao, J.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Ma, M.; Wang, Q.; Liu, H. Bitter and astringent substances in green tea: Composition, human perception mechanisms, evaluation methods and factors influencing their formation. Food Res. Int. 2022, 157, 111262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.; Choi, K.S.; Wang, S.; Adhikari, K.; Lee, J. Cold brew coffee: Consumer acceptability and characterization using the check-all-that-apply (CATA) method. Foods 2019, 8, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Hwang, I.S.; Yoon, G.; Lim, M.; Park, M.K.; Oh, J.; Kwak, H.S. Do you drink coffee, or brand? Brand effect on consumers’ liking and emotional responses to instant coffee among Korean consumers. J. Sens. Stud. 2025, 40, e70022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S.R.; Chheang, S.L.; Jin, D.; Ryan, G.S.; Ares, G. How do CATA questions work? Relationship between likelihood of selecting a term and perceived attribute intensity. J. Sens. Stud. 2023, 38, e12833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Y.; Yang, X.; Xu, B.; Yang, W.; Tong, T.; Jin, S.; Shen, C.; Rao, H.; et al. Earliest tea as evidence for one branch of the Silk Road across the Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 18955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Byun, G.I. A study on the preference and intake frequency of Korean traditional beverages. J. Korean Soc. Food Cult. 2006, 21, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effah-Manu, L.; Wireko-Manu, F.D.; Agbenorhevi, J.K.; Maziya-Dixon, B.; Oduro, I.N. Gender-disaggregated consumer testing and descriptive sensory analysis of local and new yam varieties. Foods 2023, 12, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, E.; Kim, T.H.; Powell, L.M. Beverage consumption and individual-level associations in South Korea. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, L.; Toppinen, A.; Wang, L. Cultural motives affecting tea purchase behavior under two usage situations in China: A study of renqing, mianzi, collectivism, and man-nature unity culture. J. Ethn. Foods 2021, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, S.; Chambers, E., IV; Chambers, D. Perception of pork patties with shiitake (Lentinus edode P.) mushroom powder and sodium tripolyphosphate as measured by Korean and United States consumers. J. Sens. Stud. 2005, 20, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Abb. | English Name | Korean Name | Chinese Name | Brand | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST | Suntory Oolong tea | 산토리 우롱차 | 三得利乌龙茶 | Suntory | Japan |

| SG | Sangaria Oolong tea | 산가리아 우롱차 | 三佳利乌龙茶 | Iyemon Tea House | Japan |

| CC | Coca-Cola Oolong tea | 코카콜라 우롱차 | 可口可乐乌龙茶 | Coca-Cola | Japan |

| NF | Oriental Leaf Oolong tea | 농푸 동방수예 우롱차 | 东方树叶乌龙茶 | Nongfu Spring | China |

| AS | Asahi Oolong tea | 아사히 우롱차 | 朝日乌龙茶 | ASAHI | Japan |

| KN | Golden Flowers Oolong tea | 금빛 우롱차 | 金花乌龙茶 | Keumnong Foods | Korea |

| IT | Ito En Oolong tea | 이토엔 우롱차 | 伊藤 园乌龙茶 | Ito En | Japan |

| OCB | OCOCO | 오코코 흑우롱차 | OCOCO黑乌龙茶 | OCOCO | China |

| YCB ‡ | YU-CHA | 농축 흑우롱차 | 浓缩黑乌龙 | You Cha | Japan |

| FNB | Tominaga | 토미나가 | 富永黑乌龙茶 | Funei | Japan |

| NFB | Oriental Leaf Black Oolong | 농푸 동방수예 흑우롱차 | 东方树叶黑乌龙茶 | Nongfu Spring | China |

| STB | Suntory Black Oolong | 산토리 흑우롱차 | 三得利黑乌龙茶 | Suntory | Japan |

| Chinese (n = 102) n (%) | Korean (n = 100) n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 27 (26.4) | 25 (25.0) |

| Female | 75 (73.5) | 75 (75.0) |

| Age (years) | ||

| 19–25 | 63 (61.8) | 78 (78.0) |

| 26–30 | 34 (33.3) | 12 (12.0) |

| 31–35 | 4 (3.9) | 4 (4.0) |

| 36–40 | 1 (1.0) | 2 (2.0) |

| 41–45 | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.0) |

| Tea consumption frequency per week | ||

| 0 | 10 (9.8) | 21 (21.0) |

| 1 | 37 (36.2) | 39 (39.0) |

| 2 | 18 (17.6) | 22 (22.0) |

| 3 | 13 (12.7) | 9 (9.0) |

| >4 | 24 (23.5) | 9 (9.0) |

| Type of tea consumed | ||

| Black Tea | 65 (63.7) | 73 (73.0) |

| Green Tea | 55 (53.9) | 53 (53.0) |

| Oolong Tea | 53 (52.0) | 26 (26.0) |

| Other * | 32 (31.4) | 45 (45.0) |

| Preferred drinking temperature of tea | ||

| Cold | 32 (31.4) | 30 (30.0) |

| Hot | 45 (44.1) | 43 (43.0) |

| Room temperature | 12 (11.8) | 3 (3.0) |

| No Preference | 13 (12.7) | 24 (24.0) |

| English | Chinese | Korean |

|---|---|---|

| Bitter | 苦味 | 쓴맛 |

| Sour | 酸味 | 신맛 |

| Sweet | 甜味 | 단맛 |

| Astringent | 涩味 | 떫은맛 |

| Cooling | 清爽的 | 시원한 |

| Metallic | 金属味 | 금속 맛 |

| Alkali | 碱味 | 알칼리 맛 |

| Barley Tea | 大麦茶味 | 보리차 맛 |

| Fermented | 发酵味 | 발효 맛 |

| Floral | 花香味 | 꽃향 |

| Fruity | 水果味 | 과일 맛 |

| Rosted | 烘烤味 | 구운 맛 |

| Milk | 牛奶味 | 우유 맛 |

| Oolong Tea Flavor | 乌龙茶味 | 우롱차 맛 |

| Oxidized | 氧化味 | 산화 맛 |

| Winter Melon | 冬瓜味 | 동과 맛 |

| Bitter Aftertaste | 回味苦 | 쓴 후미 |

| Sweet Aftertaste | 回味甜 | 단 후미 |

| Astringent Aftertaste | 回味涩 | 떫은 후미 |

| Clean | 干净的 | 깔끔한 |

| ST | ST2 | p-Value | IT | IT2 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese consumers | 6.02 | 6.12 | 0.614 | 6.46 | 6.46 | 0.9099 |

| Korean consumers | 6.23 | 6.35 | 0.599 | 6.65 | 6.93 | 0.153 |

| ST | ST2 | IT | IT2 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Korean consumers residing in South Korea (n = 102) | ||||||||

| Sweet | 38 | 37.3 | 30 | 29.4 | 39 | 38.2 | 35 | 34.3 |

| Bitter | 60 | 58.8 | 56 | 54.9 | 60 | 58.8 | 49 | 48.0 |

| Sour | 15 | 14.7 | 16 | 15.7 | 20 | 19.6 | 16 | 15.7 |

| Astringent | 64 | 62.7 | 69 | 67.6 | 63 | 61.8 | 65 | 63.7 |

| Barley tea | 62 | 60.8 | 64 | 62.7 | 64 | 62.7 | 67 | 65.7 |

| Roasted | 60 | 58.8 | 49 | 48.0 | 59 | 57.8 | 53 | 52.0 |

| Oxidized | 9 | 8.8 | 6 | 5.9 | 12 | 11.8 | 12 | 11.8 |

| Floral | 12 | 11.8 | 8 | 7.8 | 7 | 6.9 | 12 | 11.8 |

| Fruity | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 2.9 | 4 | 3.9 | 6 | 5.9 |

| Milk | 2 | 2.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 2.0 | 2 | 2.0 |

| Fermented | 20 | 19.6 | 12 | 11.8 | 21 | 20.6 | 19 | 18.6 |

| Oolong tea flavor | 76 | 74.5 | 83 | 81.4 | 76 | 74.5 | 74 | 72.5 |

| Metallic | 8 | 7.8 | 2 | 2.0 | 6 | 5.9 | 4 | 3.9 |

| Winter melon | 3 | 2.9 | 2 | 2.0 | 2 | 2.0 | 2 | 2.0 |

| Sweet aftertaste | 8 | 7.8 | 13 | 12.7 | 22 | 21.6 | 17 | 16.7 |

| Bitter aftertaste | 45 | 44.1 | 40 | 39.2 | 39 | 38.2 | 31 | 30.4 |

| Astringent aftertaste | 54 | 52.9 | 53 | 52.0 | 52 | 51.0 | 50 | 49.0 |

| Alkali | 2 | 2.0 | 2 | 2.0 | 2 | 2.0 | 4 | 3.9 |

| Cool | 39 | 38.2 | 46 | 45.1 | 32 | 31.4 | 37 | 36.3 |

| Clean | 26 | 25.5 | 46 | 45.1 | 33 | 32.4 | 42 | 41.2 |

| p-value | 0.2748 | 0.9905 | ||||||

| Chinese consumers residing in South Korea (n = 100) | ||||||||

| Sweet | 19 | 19.0 | 21 | 21.0 | 19 | 19.0 | 37 | 37.0 |

| Bitter | 54 | 54.0 | 55 | 55.0 | 37 | 37.0 | 45 | 45.0 |

| Sour | 21 | 21.0 | 22 | 22.0 | 13 | 13.0 | 20 | 20.0 |

| Astringent | 65 | 65.0 | 74 | 74.0 | 56 | 56.0 | 58 | 58.0 |

| Barley tea | 45 | 45.0 | 57 | 57.0 | 46 | 46.0 | 56 | 56.0 |

| Roasted | 32 | 32.0 | 36 | 36.0 | 28 | 28.0 | 28 | 28.0 |

| Oxidized | 8 | 8.0 | 6 | 6.0 | 5 | 5.0 | 9 | 9.0 |

| Floral | 5 | 5.0 | 12 | 12.0 | 16 | 16.0 | 13 | 13.0 |

| Fruity | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 3.0 | 4 | 4.0 | 5 | 5.0 |

| Milk | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.0 |

| Fermented | 14 | 14.0 | 22 | 22.0 | 7 | 7.0 | 9 | 9.0 |

| Oolong tea flavor | 71 | 71.0 | 65 | 65.0 | 68 | 68.0 | 63 | 63.0 |

| Metallic | 9 | 9.0 | 10 | 10.0 | 2 | 2.0 | 6 | 6.0 |

| Winter melon | 3 | 3.0 | 4 | 4.0 | 4 | 4.0 | 7 | 7.0 |

| Sweet aftertaste | 18 | 18.0 | 25 | 25.0 | 21 | 21.0 | 31 | 31.0 |

| Bitter aftertaste | 40 | 40.0 | 40 | 40.0 | 34 | 34.0 | 33 | 33.0 |

| Astringent aftertaste | 51 | 51.0 | 46 | 46.0 | 47 | 47.0 | 38 | 38.0 |

| Alkali | 14 | 14.0 | 17 | 17.0 | 7 | 7.0 | 7 | 7.0 |

| Cool | 27 | 27.0 | 29 | 29.0 | 47 | 47.0 | 48 | 48.0 |

| Clean | 21 | 21.0 | 18 | 18.0 | 36 | 36.0 | 34 | 34.0 |

| p-value | 0.9205 | 0.7165 | ||||||

| Overall Liking | Transparent Appearance Liking | Color Liking | Astringency Liking | Aftertaste Liking | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese consumers residing in South Korea | ||||||||||

| AS | 5.9 | c | 6.4 | bc | 6.1 | ab | 5.5 | fg | 5.5 | cd |

| CC | 5.7 | c | 6.0 | efg | 6.1 | ab | 5.7 | cdefg | 5.6 | cd |

| IT | 5.8 | c * | 6.1 | def | 6.2 | ab | 5.6 | defg | 5.6 | cd |

| KN | 5.9 | c | 6.6 | ab | 6.2 | ab | 6.0 | abcd | 6.0 | bc |

| NF | 6.4 | ab | 6.8 | a | 6.3 | ab | 6.2 | abc | 6.1 | bcd |

| SG | 6.5 | a | 6.3 | bcde | 6.3 | ab | 6.0 | abc | 6.2 | bcd |

| ST | 6.0 | c | 6.0 | def | 6.1 | ab | 5.6 | efg | 5.7 | bcd |

| OCB | 6.8 | a * | 6.3 | bcde | 6.4 | a | 6.4 | a | 6.6 | a * |

| NFB | 6.0 | bc * | 6.4 | bcd | 6.3 | ab | 5.7 | cdef | 5.8 | bcd * |

| STB | 5.8 | c | 5.6 | g | 5.6 | c | 5.4 | fg | 5.4 | d |

| FNB | 5.6 | c | 5.8 | fg | 5.9 | bc | 5.3 | g | 5.4 | d |

| YCB | 5.7 | c * | 6.1 | cdef * | 6.1 | ab * | 5.9 | bcde | 5.7 | bcd |

| LSD | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.44 | |||||

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0315 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||||

| Korean consumers residing in South Korea | ||||||||||

| AS | 6.3 | b | 6.7 | ab | 6.5 | bc | 5.5 | cd | 5.7 | bcd |

| CC | 5.9 | bc | 6.6 | ab | 6.2 | cd | 5.9 | bc | 5.9 | ab |

| IT | 6.0 | b * | 6.8 | a | 6.7 | ab | 5.7 | cd | 5.7 | bc |

| KN | 5.5 | cd | 5.8 | c | 4.9 | f | 5.9 | bc | 5.7 | bc |

| NF | 6.1 | b | 6.6 | ab | 6.0 | d | 5.9 | bc | 5.9 | ab |

| SG | 6.9 | a | 6.9 | a | 7.1 | a | 6.1 | ab | 6.3 | a |

| ST | 6.2 | b | 6.4 | b | 6.2 | cd | 5.9 | bc | 5.9 | ab |

| OCB | 6.2 | b * | 6.4 | b | 6.1 | cd | 6.4 | a | 6.2 | a * |

| NFB | 5.5 | cd * | 6.6 | ab | 6.5 | bc | 5.7 | bcd | 5.3 | cd * |

| STB | 5.8 | bc | 5.9 | c | 5.4 | e | 5.7 | bcd | 5.7 | bc |

| FNB | 5.4 | cd | 5.8 | c | 5.3 | ef | 5.3 | d | 5.2 | d |

| YCB | 5.1 | d * | 4.5 | d * | 4.3 | g * | 5.8 | bcd | 5.5 | bcd |

| LSD | 0.47 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.49 | |||||

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0005 | <0.0001 | |||||

| Oolong Tea Flavor Intensity | Bitterness Intensity | Astringency Intensity | Aftertaste Intensity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese consumers residing in South Korea | ||||||||

| AS | 5.7 ± 1.52 | cd | 5.5 ±1.65 | bcd | 6.0 ± 1.62 | ab | 6.2 ± 1.34 | bc |

| CC | 5.7 ± 1.79 | cd | 5.2 ± 1.98 | cd | 5.1 ± 1.84 | de | 5.6 ± 1.66 | dc |

| IT | 6.1 ± 1.58 | abc | 5.3 ± 1.80 | cd | 5.6 ± 1.85 | c | 6.0 ± 1.80 | bc |

| KN | 3.6 ± 1.58 | e | 2.7 ± 1.80 | f | 3.1 ± 1.85 | f | 3.9 ± 1.80 | e |

| NF | 5.4 ± 1.70 | d | 4.2 ± 1.66 | e | 4.7 ± 1.85 | e | 5.4 ± 1.63 | dc |

| SG | 6.0 ± 1.75 | abc | 5.0 ± 1.66 | d | 5.3 ± 1.57 | cd | 5.6 ± 1.59 | cd |

| ST | 6.4 ± 1.71 | abc | 5.8 ± 1.70 | b | 6.2 ± 1.51 | a | 6.3 ± 1.56 | ab |

| OCB | 6.1 ± 1.57 | abc | 4.4 ± 1.67 | e | 4.8 ± 1.74 | e | 5.9 ± 1.46 | bc |

| NFB | 5.9 ± 1.64 | bc | 5.5 ± 1.62 | bcd | 5.7 ± 1.66 | bc | 6.2 ± 1.55 | ab |

| STB | 6.1 ± 1.62 | abc | 5.8 ± 1.61 | b | 6.2 ± 1.62 | a | 6.2 ± 1.57 | ab |

| FNB | 6.2 ± 1.65 | abc | 6.2 ± 1.70 | a | 6.4 ± 1.60 | a | 6.6 ± 1.58 | a |

| YCB | 3.4 ± 1.78 | e | 2.6 ± 1.49 | f | 2.7 ± 1.57 | f | 3.5 ± 1.72 | f |

| LSD | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.40 | ||||

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Korean consumers residing in South Korea | ||||||||

| AS | 6.0 ± 1.49 | abc | 5.4 ± 1.82 | b | 5.7 ± 1.96 | ab | 5.9 ± 1.67 | bc |

| CC | 5.8 ± 1.80 | bc | 5.0 ± 1.90 | cd | 5.0 ± 2.02 | cd | 5.8 ± 1.87 | bc |

| IT | 6.0 ± 1.58 | abc | 5.0 ± 1.90 | bc | 5.3 ± 1.93 | bcd | 5.8 ± 1.50 | bc |

| KN | 3.4 ± 1.46 | e | 3.0 ± 1.60 | e | 3.4 ± 2.00 | f | 4.2 ± 1.80 | e |

| NF | 5.1 ± 1.66 | d | 4.3 ± 1.88 | d | 4.9 ± 1.87 | d | 5.1 ± 1.65 | d |

| SG | 5.9 ± 1.71 | bc | 5.2 ± 1.83 | bc | 5.4 ± 1.84 | bc | 5.6 ± 1.67 | c |

| ST | 6.3 ± 1.60 | a | 5.4 ± 1.78 | b | 5.7 ± 1.87 | ab | 5.8 ± 1.68 | bc |

| OCB | 5.6 ± 1.64 | c | 4.2 ± 1.70 | d | 4.4 ± 1.87 | e | 5.6 ± 1.54 | c |

| NFB | 5.8 ± 1.52 | bc | 5.1 ± 1.87 | bc | 5.2 ± 1.86 | cd | 5.7 ± 1.69 | bc |

| STB | 6.1 ± 1.72 | ab | 5.2 ± 1.94 | bc | 5.4 ± 2.03 | bc | 6.0 ± 1.76 | b |

| FNB | 6.3 ± 1.54 | a | 6.0 ± 1.80 | a | 6.1 ± 1.73 | a | 6.5 ± 1.43 | a |

| YCB | 2.9 ± 1.53 | f | 2.5 ± 1.26 | f | 2.6 ± 1.35 | g | 3.2 ± 1.53 | f |

| LSD | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.40 | ||||

| p-value | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Chinese Consumers (n = 102) | Korean Consumers (n = 100) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Rating | CATA Freq. | Mean Rating (n) | t-Value | p-Value | Mean Rating | CATA Freq. | Mean Rating (n) | t-Value | p-Value | |||

| Sample | Not Checked | Checked | Not Checked | Checked | ||||||||

| Oolong Tea Flavor | ||||||||||||

| ST | 6.4 | 71 | 5.4 (31) | 6.8 (71) | 3.597 | 0.0008 | 6.3 | 78 | 5.4 (22) | 6.5 (78) | 2.891 | 0.007 |

| IT | 6.0 | 68 | 5.1 (34) | 6.5 (68) | 3.909 | 0.0003 | 5.9 | 82 | 5.7 (18) | 6.0 (82) | 0.593 | 0.5581 |

| CC | 5.8 | 50 | 5.0 (52) | 6.5 (50) | 4.757 | <0.0001 | 5.8 | 64 | 5.2 (36) | 6.1 (64) | 2.118 | 0.0385 |

| NF | 5.4 | 67 | 4.2 (35) | 6.1 (67) | 6.069 | <0.0001 | 5.1 | 67 | 4.6 (33) | 5.3 (67) | 2.048 | 0.0453 |

| AS | 5.7 | 55 | 5.1 (47) | 6.3 (55) | 4.074 | <0.0001 | 6.0 | 75 | 5.3 (25) | 6.2 (75) | 2.814 | 0.0074 |

| KN | 3.6 | 33 | 3.2 (69) | 4.4 (33) | 3.176 | 0.0023 | 3.4 | 40 | 3.3 (60) | 3.6 (40) | 0.961 | 0.3393 |

| SG | 6.1 | 59 | 5.5 (43) | 6.5 (59) | 3.132 | 0.0024 | 6.0 | 69 | 5.4 (31) | 6.2 (69) | 2.581 | 0.0127 |

| OCB | 6.1 | 58 | 5.4 (44) | 6.5 (58) | 3.688 | 0.0004 | 5.6 | 57 | 5.0 (43) | 6.1 (57) | 3.290 | 0.0014 |

| YCB | 3.5 | 28 | 2.9 (74) | 4.9 (28) | 6.196 | <0.0001 | 2.9 | 28 | 3.0 (72) | 2.9 (28) | −0.302 | 0.764 |

| FNB | 6.2 | 56 | 5.8 (46) | 6.6 (56) | 2.447 | 0.0162 | 6.3 | 71 | 5.6 (29) | 6.6 (71) | 2.681 | 0.0105 |

| NFB | 5.9 | 58 | 5.4 (44) | 6.4 (58) | 3.054 | 0.0032 | 5.8 | 69 | 6.0 (31) | 5.7 (69) | −0.927 | 0.3568 |

| STB | 6.1 | 65 | 5.8 (37) | 6.3 (65) | 1.483 | 0.1434 | 6.1 | 69 | 5.9 (31) | 6.2 (69) | 0.681 | 0.4979 |

| Bitterness | ||||||||||||

| ST | 5.8 | 54 | 5.0 (48) | 6.5 (54) | 4.746 | <0.0001 | 5.4 | 61 | 4.3 (39) | 6.1 (61) | 5.555 | <0.0001 |

| IT | 5.0 | 37 | 4.7 (65) | 5.7 (37) | 3.529 | 0.0006 | 5.1 | 56 | 4.4 (44) | 5.7 (56) | 4.558 | <0.0001 |

| CC | 5.2 | 49 | 4.5 (53) | 6.0 (49) | 4.075 | <0.0001 | 5.0 | 54 | 3.9 (46) | 5.9 (54) | 6.141 | <0.0001 |

| NF | 4.2 | 26 | 3.9 (76) | 5.3 (26) | 4.163 | 0.0001 | 4.3 | 40 | 3.8 (60) | 5.0 (40) | 3.33 | 0.0012 |

| AS | 5.5 | 39 | 5.0 (63) | 6.2 (39) | 3.738 | 0.0003 | 5.4 | 58 | 4.3 (42) | 6.2 (58) | 5.598 | <0.0001 |

| KN | 2.7 | 14 | 2.5 (88) | 4.1 (14) | 3.613 | 0.0021 | 3.0 | 25 | 2.9 (75) | 3.5 (25) | 1.467 | 0.1513 |

| SG | 5.3 | 47 | 4.6 (55) | 6.2 (47) | 5.237 | <0.0001 | 5.0 | 53 | 4.0 (47) | 5.9 (53) | 5.460 | <0.0001 |

| OCB | 4.4 | 24 | 4.2 (78) | 5.3 (24) | 3.399 | 0.0015 | 4.2 | 33 | 3.6 (67) | 5.5 (33) | 6.555 | <0.0001 |

| YCB | 2.6 | 6 | 2.5 (96) | 4.0 (6) | 2.771 | 0.0331 | 2.5 | 13 | 2.5 (87) | 2.5 (13) | −0.062 | 0.9512 |

| FNB | 6.2 | 65 | 5.2 (37) | 6.8 (65) | 4.940 | <0.0001 | 6.0 | 72 | 6.0 (28) | 5.9 (72) | −0.048 | 0.9616 |

| NFB | 5.5 | 53 | 4.9 (49) | 6.0(53) | 3.510 | 0.0007 | 5.1 | 62 | 5.0 (38) | 5.2 (62) | 0.420 | 0.6755 |

| STB | 5.8 | 53 | 5.1 (49) | 6.4 (53) | 4.661 | <0.0001 | 5.2 | 58 | 5.2 (42) | 5.3 (58) | 0.231 | 0.8178 |

| Astringency | ||||||||||||

| ST | 6.1 | 65 | 5.5 (37) | 6.5 (65) | 3.236 | 0.0019 | 5.3 | 66 | 4.9 (34) | 5.5 (66) | 1.289 | 0.2021 |

| IT | 5.3 | 56 | 4.6 (46) | 5.9 (56) | 4.146 | <0.0001 | 5.4 | 68 | 5.0 (32) | 5.6 (68) | 1.837 | 0.0704 |

| CC | 5.1 | 50 | 4.2 (52) | 6.0 (50) | 6.017 | <0.0001 | 5.0 | 52 | 3.9 (48) | 6.0 (52) | 6.083 | <0.0001 |

| NF | 4.7 | 48 | 3.9 (54) | 5.6 (48) | 5.284 | <0.0001 | 4.9 | 58 | 4.0 (42) | 5.5 (58) | 4.210 | <0.0001 |

| AS | 6.0 | 69 | 5.1 (33) | 6.5 (69) | 4.495 | <0.0001 | 5.7 | 60 | 4.2 (40) | 6.7 (60) | 7.975 | <0.0001 |

| KN | 3.1 | 19 | 2.7 (83) | 4.9 (19) | 5.064 | <0.0001 | 3.4 | 33 | 3.3 (67) | 3.6 (33) | 0.932 | 0.3546 |

| SG | 5.6 | 57 | 4.6 (45) | 6.4 (57) | 5.690 | <0.0001 | 5.8 | 59 | 5.2 (41) | 6.2 (59) | 3.603 | 0.0005 |

| OCB | 4.8 | 28 | 4.7 (74) | 5.2 (28) | 1.593 | 0.1172 | 4.4 | 37 | 3.8 (63) | 5.4 (37) | 4.523 | <0.0001 |

| YCB | 2.7 | 16 | 2.4 (86) | 4.2 (16) | 5.177 | <0.0001 | 2.6 | 23 | 2.5 (77) | 2.7 (23) | 0.499 | 0.6201 |

| FNB | 6.4 | 76 | 5.3 (26) | 6.8 (76) | 4.143 | 0.0002 | 6.1 | 68 | 5.9 (32) | 6.2 (68) | 0.840 | 0.4049 |

| NFB | 5.7 | 59 | 5.0 (43) | 6.2 (59) | 3.853 | 0.0002 | 5.2 | 58 | 5.4 (42) | 5.0 (58) | −0.880 | 0.3814 |

| STB | 6.2 | 64 | 5.5 (38) | 6.7 (64) | 3.363 | 0.0015 | 5.4 | 65 | 5.5 (35) | 5.3 (65) | −0.380 | 0.7045 |

| Aftertaste | ||||||||||||

| ST | 6.3 | 65 | 5.9 (37) | 6.5 (65) | 2.138 | 0.0355 | 5.8 | 66 | 5.2 (34) | 6.2 (66) | 2.771 | 0.0072 |

| IT | 5.6 | 56 | 5.3 (46) | 5.9 (56) | 2.092 | 0.0394 | 5.6 | 68 | 5.3 (32) | 5.7 (68) | 1.377 | 0.1735 |

| CC | 5.6 | 50 | 5.1 (52) | 6.1 (50) | 3.338 | 0.0012 | 5.8 | 52 | 5.0 (48) | 6.5 (52) | 4.042 | 0.0001 |

| NF | 5.5 | 48 | 5.3 (54) | 5.6 (48) | 0.964 | 0.3372 | 5.1 | 58 | 4.5 (42) | 5.6 (58) | 3.178 | 0.0021 |

| AS | 6.2 | 69 | 5.6 (33) | 6.6 (69) | 3.249 | 0.002 | 5.9 | 60 | 5.2 (40) | 6.4 (60) | 3.325 | 0.0014 |

| KN | 3.9 | 19 | 3.9 (83) | 4.3 (19) | 1.081 | 0.2877 | 4.2 | 33 | 4.2 (67) | 4.3 (33) | 0.387 | 0.6995 |

| SG | 6.0 | 57 | 5.2 (45) | 6.5 (57) | 3.576 | 0.0006 | 5.8 | 59 | 5.2 (41) | 6.2 (59) | 3.630 | 0.0005 |

| OCB | 5.9 | 28 | 6.0 (74) | 5.5 (28) | −1.519 | 0.1357 | 5.6 | 37 | 5.3 (63) | 6.1 (37) | 2.636 | 0.0103 |

| YCB | 3.5 | 16 | 3.4 (86) | 4.2 (16) | 1.803 | 0.0863 | 3.2 | 23 | 3.2 (77) | 3.2 (23) | 0.187 | 0.8526 |

| FNB | 6.6 | 76 | 5.8 (26) | 6.9 (76) | 2.545 | 0.0154 | 6.4 | 68 | 6.2 (32) | 6.6 (68) | 1.034 | 0.306 |

| NFB | 6.2 | 59 | 5.9 (43) | 6.5 (59) | 1.692 | 0.0949 | 5.7 | 58 | 5.6 (42) | 5.9 (58) | 0.837 | 0.4052 |

| STB | 6.2 | 64 | 5.7 (38) | 6.5 (64) | 2.234 | 0.0294 | 6.0 | 65 | 6.2 (35) | 5.9 (65) | −0.828 | 0.4097 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Su, B.; Lee, J. Chinese and Korean Consumers’ Preferences for Oolong and Black Oolong Teas. Foods 2025, 14, 3327. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14193327

Su B, Lee J. Chinese and Korean Consumers’ Preferences for Oolong and Black Oolong Teas. Foods. 2025; 14(19):3327. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14193327

Chicago/Turabian StyleSu, Baihan, and Jeehyun Lee. 2025. "Chinese and Korean Consumers’ Preferences for Oolong and Black Oolong Teas" Foods 14, no. 19: 3327. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14193327

APA StyleSu, B., & Lee, J. (2025). Chinese and Korean Consumers’ Preferences for Oolong and Black Oolong Teas. Foods, 14(19), 3327. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14193327