Assessing the Applicability of a Partial Alcohol Reduction Method to the Fine Wine Analytical Composition of Pinot Gris

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Climate Change Induced High Sugar and Alcohol Contents

1.2. Possible Methods for Alcohol Reduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Wine, Alcohol Reduction, and Sampling

2.2. Wine Analytics

2.3. Statistical Evaluation

3. Results

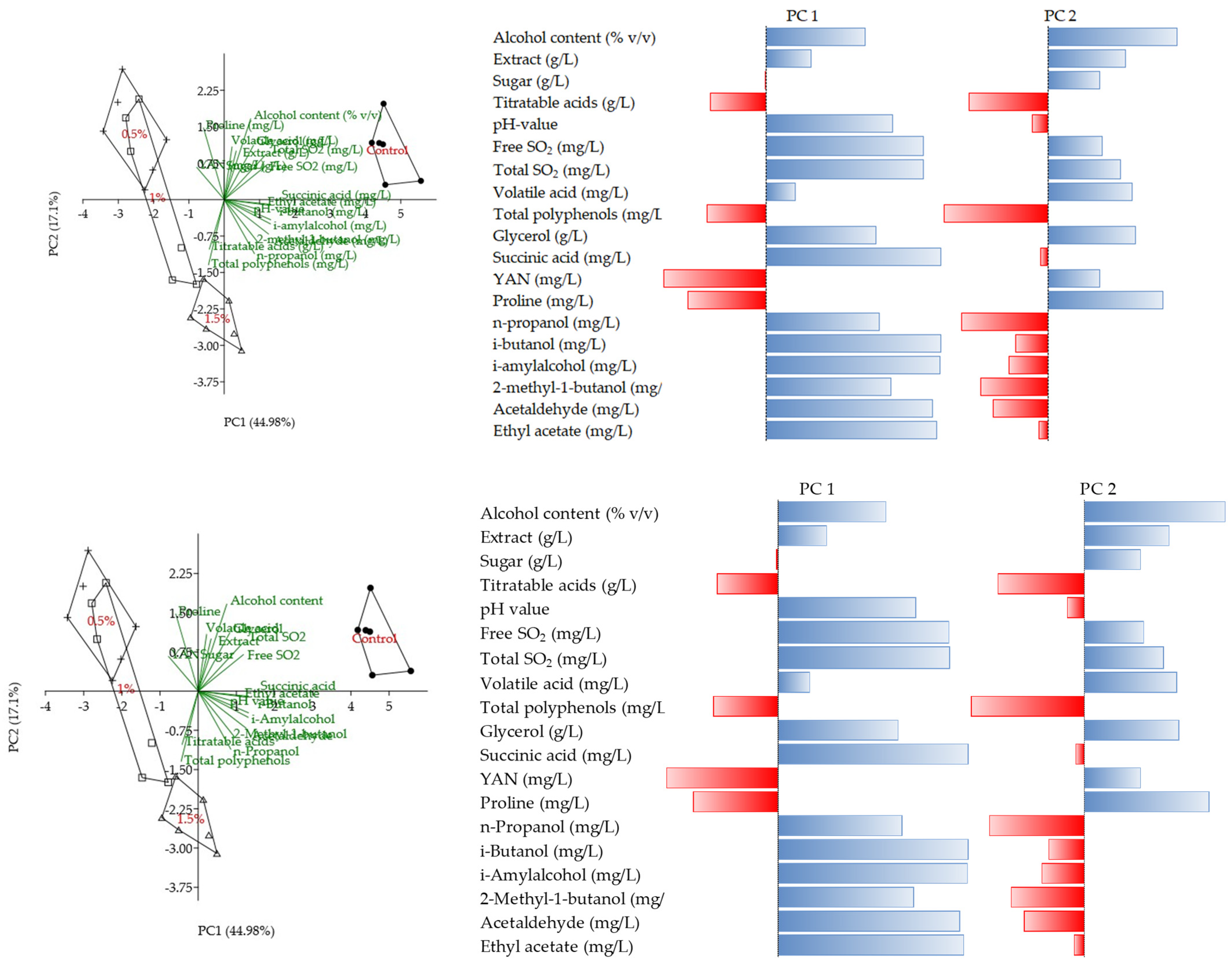

3.1. Multivariate Structure of the Wine Composition (PCA Results)

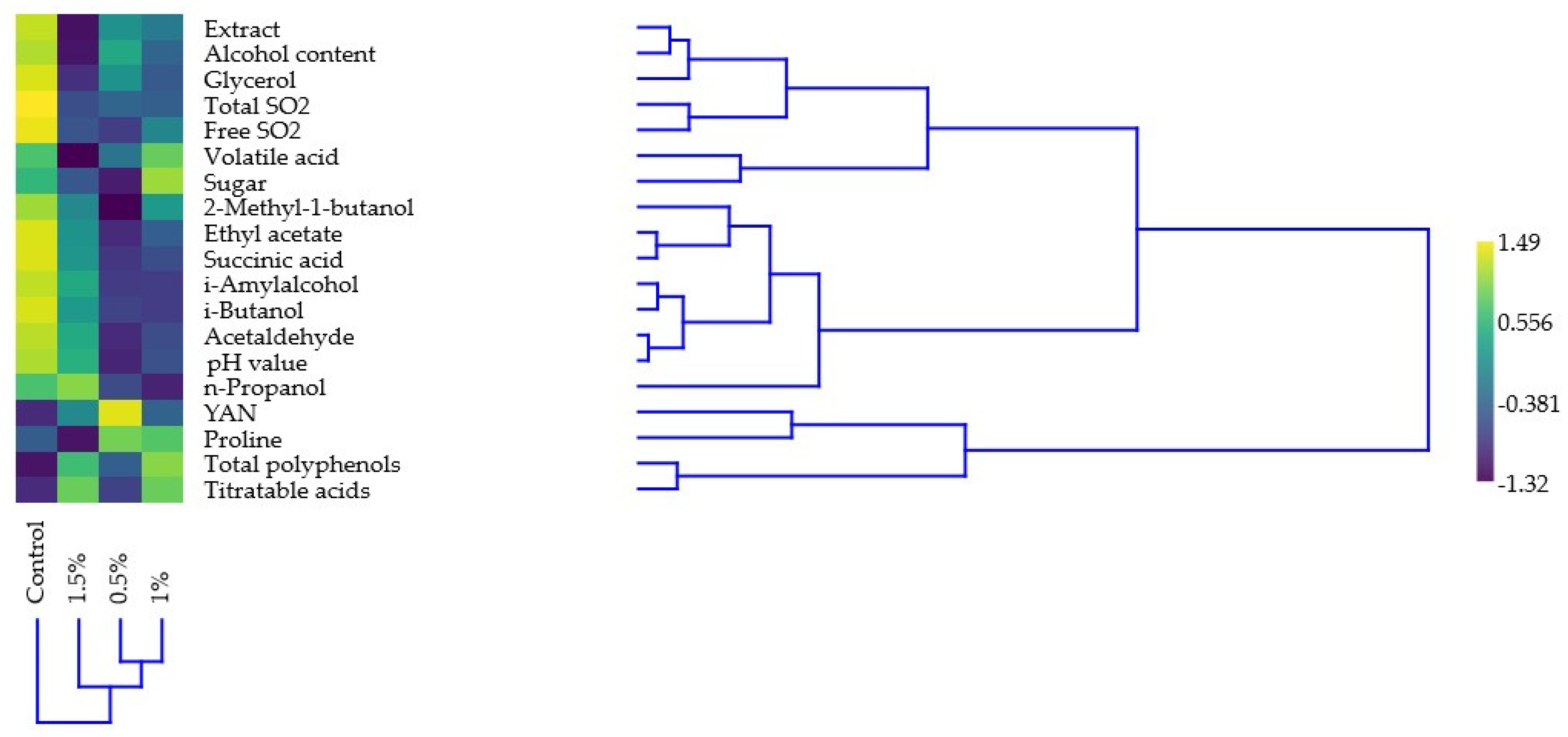

3.2. Multivariate Clustering of Treatments by Chemical Parameters

3.3. Effect of Alcohol Reduction on the Wine Chemical Composition (ANOVA)

3.4. Regression Models Reveal Key Trends Across Treatments

3.5. Relationships Between the Alcohol Content and Chemical Components

4. Discussion

4.1. Climate Change’s Consequenses on Wine Profiles

4.2. Wine Chemical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2nd National Climate Change Strategy. 2018. Available online: https://mkogy.jogtar.hu/jogszabaly?docid=A18H0023.OGY (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Erbach, G.; Meinardi, C. Hungary’s Climate Action Strategy. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2025/769532/EPRS_BRI(2025)769532_EN.pdf (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Rienth, M.; Torregrosa, L.; Luchaire, N.; Chatbanyong, R.; Lecourieux, D.; Kelly, M.T.; Romieu, C. Day and night heat stress trigger different transcriptomic responses in green and ripening grapevine (Vitis vinifera) fruit. BMC Plant Biol. 2014, 14, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchêne, E.; Schneider, C. Grapevine and climatic changes: A glance at the situation in Alsace. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 25, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palliotti, A.; Tombesi, S.; Silvestroni, O.; Lanari, V.; Gatti, M.; Poni, S. Changes in vineyard establishment and canopy management urged by earlier climate-related grape ripening: A review. Sci. Hortic. 2014, 178, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Lüscher, J.; Kizildeniz, T.; Vučetić, V.; Dai, Z.; Luedeling, E.; van Leeuwen, C.; Gomès, E.; Pascual, I.; Juan José, I.; Morales, F.; et al. Sensitivity of Grapevine Phenology to Water Availability, Temperature and CO2 Concentration. Front. Environ. Sci. 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Leeuwen, C.; Darriet, P. The Impact of Climate Change on Viticulture and Wine Quality. J. Wine Econ. 2016, 11, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadras, V.O.; Moran, M.A. Elevated temperature decouples anthocyanins and sugars in berries of Shiraz and Cabernet Franc. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2012, 18, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spayd, S.E.; Tarara, J.M.; Mee, D.L.; Ferguson, J.C. Separation of Sunlight and Temperature Effects on the Composition of Vitis vinifera cv. Merlot Berries. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2002, 53, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Goto-Yamamoto, N.; Kitayama, M.; Hashizume, K. Loss of anthocyanins in red-wine grape under high temperature. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 1935–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordão, A.M.; Vilela, A.; Cosme, F. From sugar of grape to alcohol of wine: Sensorial impact of alcohol in wine. Beverages 2015, 1, 292–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba, A.; Ovington, L.; Moran, C. Consumer demand for low-alcohol wine in an Australian sample. Int. J. Wine Res. 2013, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meillon, S.; Urbano, C.; Guillot, G.; Schlich, P. Acceptability of partially dealcoholized wines—Measuring the impact of sensory and information cues on overall liking in real-life settings. Food Qual. Prefer. 2010, 21, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, N.J.; Thompson, K.E. Reasoned action theory: An application to alcohol-free beer. J. Mark. Pr. Appl. Mark. Sci. 1996, 2, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysochou, P. Drink to get drunk or stay healthy? Exploring consumers’ perceptions, motives and preferences for light beer. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 31, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization of Vine and Wine (OIV). Available online: https://www.oiv.int/public/medias/1431/oiv-oeno-394a-2012-en.pdf (accessed on 27 May 2025).

- Biyela, B.N.E.; du Toit, W.J.; Divol, B.; Malherbe, D.F.; van Rensburg, P. The Production of Reduced-Alcohol Wines Using Gluzyme Mono® 10.000 BG-Treated Grape Juice. S. Afr. J. Enol. Vitic. 2009, 30, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röcker, J.; Schmitt, M.; Pasch, L.; Ebert, K.; Grossmann, M. The Use of Glucose Oxidase and Catalase for the Enzymatic Reduction of the Potential Ethanol Content in Wine. Food Chem. 2016, 210, 660–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutyna, D.R.; Varela, C.; Henschke, P.A.; Chambers, P.J.; Stanley, G.A. Microbiological Approaches to Lowering Ethanol Concentration in Wine. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 21, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossouw, D.; Bauer, F.F. Exploring the phenotypic space of non-Saccharomyces wine yeast biodiversity. Food Microbiol. 2016, 55, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidtke, L.M.; Blackman, J.W.; Agboola, S.O. Production Technologies for Reduced Alcoholic Wines. J. Food Sci. 2012, 77, R25–R41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.N.; Wang, R. Reverse Osmosis Membrane Separation Technology; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenten, I.G. Khoiruddin Reverse Osmosis Applications: Prospect and Challenges. Desalination 2016, 391, 112–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, K.; Dick, R.; Moulin, G.; Galzy, P. A Reverse Osmosis for the Production of Low Ethanol Content Wine. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1986, 37, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meillon, S.; Urbano, C.; Schlich, P. Contribution of the Temporal Dominance of Sensations (TDS) Method to the Sensory Description of Subtle Differences in Partially Dealcoholized Red Wines. Food Qual. Prefer. 2009, 20, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varavuth, S.; Jiraratananon, R.; Atchariyawut, S. Experimental Study on Dealcoholization of Wine by Osmotic Distillation Process. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2009, 66, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, S.; Guaita, M.; Petrozziello, M.; Ciambotti, A.; Panero, L.; Solomita, M.; Bosso, A. Comparison of the physicochemical and volatile composition of wine fractions obtained by two different dealcoholization techniques. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdőss, T. (Ed.) Borvizsgálati Módszerek; Mezőgazdasági Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 1986; pp. 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A. Past: Paleontological statistics software package for educaton and data anlysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, S.P.; Davies, C. Molecular biology of grape berry ripening. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2000, 6, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drappier, J.; Thibon, C.; Rabot, A.; Geny-Denis, L. Relationship between wine composition and temperature: Impact on Bordeaux wine typicity in the context of global warming—Review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, C.; Dry, P.R.; Kutyna, D.R.; Francis, I.L.; Henschke, P.A.; Curtin, C.D.; Chambers, P.J. Strategies for reducing alcohol concentration in wine. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2015, 21, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, F.E.; Ma, T.Z.; Salifu, R.; Wang, J.; Jiang, Y.M.; Zhang, B.; Han, S.Y. Techniques for dealcoholization of wines: Their impact on wine phenolic composition, volatile composition, and sensory characteristics. Foods 2021, 10, 2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambuti, A.; Rinaldi, A.; Lisanti, M.T.; Pessina, R.; Moio, L. Partial dealcoholisation of red wines by membrane contactor technique: Influence on colour, phenolic compounds and saliva precipitation index. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2011, 233, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, L.; Russo, P.; Albanese, D.; Di Matteo, M. Evolution of quality parameters during red wine dealcoholization by osmotic distillation. Food Chem. 2013, 140, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lisanti, M.T.; Gambuti, A.; Genovese, A.; Piombino, P.; Moio, L. Partial Dealcoholization of Red Wines by Membrane Contactor Technique: Effect on Sensory Characteristics and Volatile Composition. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013, 6, 2289–2305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Plaza, E.; López-Nicolás, J.M.; López-Roca, J.M.; Martínez-Cutillas, A. Dealcoholization of wine. Behaviour of the aroma components during the process. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 1999, 32, 384–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Control Wine | 0.5% | 1% | 1.5% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wine basic analysis | ||||

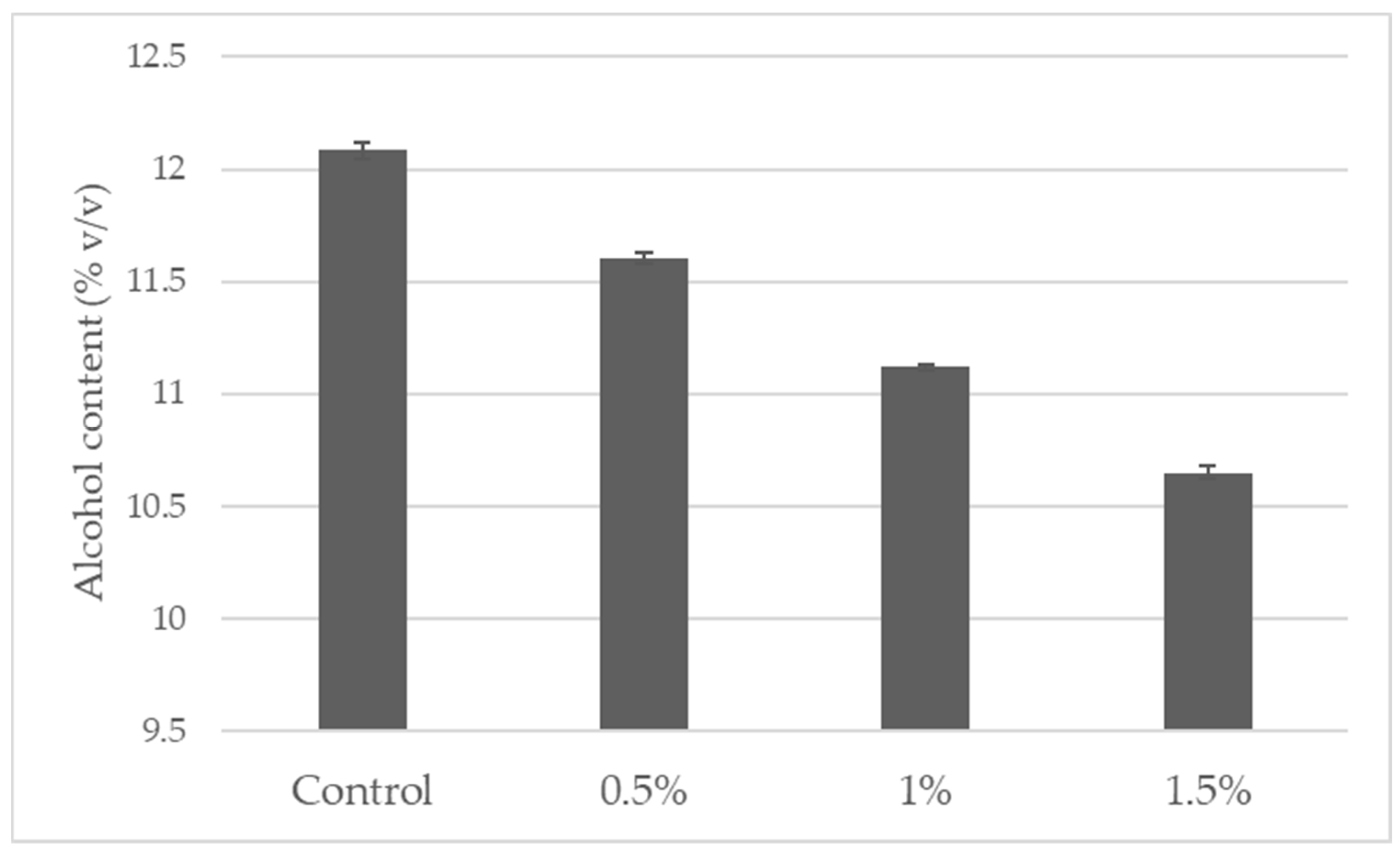

| Alcohol content (% v/v) | 12.08 ± 0.08 a | 11.61 ± 0.04 b | 11.12 ± 0.03 c | 10.65 ± 0.06 d |

| Extract (g/L) | 24.1 ± 0.44 | 23.9 ± 0.25 | 23.8 ± 0.16 | 23.7 ± 0.55 |

| Sugar (g/L) | 1.9 ± 0.12 | 1.8 ± 0.05 | 1.9 ± 0.15 | 1.8 ± 0.1 |

| Titratable acids (g/L) | 7.8 ± 0.12 b | 7.8 ± 0.11 ab | 7.9 ± 0.08 a | 7.9 ± 0.08 a |

| pH value | 3.5 ± 0.01 a | 3.51 ± 0.01 bc | 3.51 ± 0.01 b | 3.53 ± 0.01 ab |

| Sulfur dioxide fractions | ||||

| Free SO2 (mg/L) | 37. ± 0.82 a | 28 ± 1.26 c | 31 ± 1.03 b | 29 ± 1.1 c |

| Total SO2 (mg/L) | 113 ± 1.51 a | 103 ± 1.1 b | 102 ± 1.03 b | 101 ± 1.51 b |

| Fermentation by-products | ||||

| Volatile acids (mg/L) | 0.28 ± 0.03 a | 0.26 ± 0.03 ab | 0.28 ± 0.03 a | 0.23 ± 0.02 b |

| n-Propanol (mg/L) | 38.2 ± 1.03 a | 35.6 ± 0.67 ab | 34.9 ± 0.67 b | 38.7 ± 2.49 a |

| i-Butanol (mg/L) | 15.8 ± 0.21 a | 13.8 ± 0.45 b | 13.7 ± 0.51 b | 14.7 ± 0.43 ab |

| i-Amylalcohol (mg/L) | 121.0 ± 0.43 a | 105.6 ± 2.2 b | 105.7 ± 1.56 b | 114.7 ± 2.51 ab |

| 2-Methyl-1-butanol (mg/L) | 20.2 ± 0.15 a | 17.0 ± 0.29 b | 19.0 ± 2.49 ab | 18.7 ± 0.4 ab |

| Acetaldehyde (mg/L) | 36.8 ± 1.56 a | 31.6 ± 1.22 b | 32.4 ± 0.87 b | 34.9 ± 0.42 ab |

| Ethyl acetate (mg/L) | 49.1 ± 1.98 a | 21.6 ± 4.52 c | 27.6 ± 0.53 bc | 34.6 ± 3.9 ab |

| Glycerol (g/L) | 6.2 ± 0.14 a | 5.9 ± 0.14 ab | 5.8 ± 0.12 b | 5.7 ± 0.24 b |

| Succinic acid (mg/L) | 1.7 ± 0.05 a | 1.3 ± 0.06 c | 1.3 ± 0.06 c | 1.5 ± 0.02 b |

| Nitrogen-related compounds | ||||

| YAN (mg/L) | 209 ± 6.62 b | 221 ± 3.43 a | 212 ± 6.55 b | 214 ± 3.56 ab |

| Proline (mg/L) | 107 ± 9.38 | 118 ± 11.04 | 117 ± 16.91 | 102 ± 7.07 |

| Phenolic content | ||||

| Total polyphenols (mg/L) | 371 ± 3.56 b | 374 ± 2.48 ab | 379 ± 5.01 a | 378 ± 4.71 ab |

| Slope | Error | Intercept | Error | r | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic wine components | ||||||

| Extract (g/L) | 0.2908 | 0.1379 | 20.575 | 1.5682 | 0.4102 | p < 0.05 |

| Sugar (g/L) | 0.0096 | 0.0422 | 1.7579 | 0.48 | 0.0483 | 0.8226 |

| Titratable acids (g/L) | −0.1315 | 0.0387 | 9.3653 | 0.44 | −0.5869 | p < 0.01 |

| pH value | 0.0049 | 0.0054 | 3.4636 | 0.0611 | 0.1907 | 0.3721 |

| Sulfur dioxide fractions | ||||||

| Free SO2 (mg/L) | 4.6966 | 1.1665 | −21.869 | 13.27 | 0.6513 | p < 0.01 |

| Total SO2 (mg/L) | 7.391 | 1.2151 | 21.264 | 13.823 | 0.7919 | p < 0.01 |

| Fermentation by-products | ||||||

| Volatile acid (mg/L) | 0.0244 | 0.012 | −0.0148 | 0.136 | 0.3989 | 0.0535 |

| n-Propanol (mg/L) | −0.0769 | 0.826 | 37.758 | 9.3968 | −0.0199 | 0.9266 |

| i-Butanol (mg/L) | 0.7103 | 0.3369 | 6.4872 | 3.8326 | 0.41 | p < 0.05 |

| i-Amylalcohol (mg/L) | 3.9473 | 2.517 | 66.954 | 28.634 | 0.3171 | 0.1311 |

| 2-Methyl-1-butanol (mg/L) | 0.4535 | 0.6408 | 13.605 | 7.2903 | 0.1492 | 0.4866 |

| Acetaldehyde (mg/L) | 1.1055 | 0.8748 | 21.4 | 9.952 | 0.2601 | 0.2196 |

| Ethyl acetate (mg/L) | 7.4965 | 3.8954 | −51.931 | 44.315 | 0.3796 | 0.0673 |

| Glycerol (g/L) | 0.3278 | 0.0603 | 2.2006 | 0.686 | 0.7571 | p < 0.01 |

| Succinic acid (mg/L) | 0.1435 | 0.0658 | −0.1142 | 0.748 | 0.4218 | p < 0.05 |

| Nitrogen-related compounds | ||||||

| YAN (mg/L) | −1.0863 | 2.6475 | 226.76 | 30.118 | −0.0871 | 0.6855 |

| Proline (mg/L) | 4.6535 | 4.9326 | 58.496 | 56.114 | 0.1972 | 0.3557 |

| Phenolic content | ||||||

| Total polyphenols (mg/L) | −5.1619 | 1.5732 | 434.53 | 17.897 | −0.5732 | p < 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nyitrainé Sárdy, D.Á.; Bodor-Pesti, P.; Steckl, S. Assessing the Applicability of a Partial Alcohol Reduction Method to the Fine Wine Analytical Composition of Pinot Gris. Foods 2025, 14, 2738. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14152738

Nyitrainé Sárdy DÁ, Bodor-Pesti P, Steckl S. Assessing the Applicability of a Partial Alcohol Reduction Method to the Fine Wine Analytical Composition of Pinot Gris. Foods. 2025; 14(15):2738. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14152738

Chicago/Turabian StyleNyitrainé Sárdy, Diána Ágnes, Péter Bodor-Pesti, and Szabina Steckl. 2025. "Assessing the Applicability of a Partial Alcohol Reduction Method to the Fine Wine Analytical Composition of Pinot Gris" Foods 14, no. 15: 2738. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14152738

APA StyleNyitrainé Sárdy, D. Á., Bodor-Pesti, P., & Steckl, S. (2025). Assessing the Applicability of a Partial Alcohol Reduction Method to the Fine Wine Analytical Composition of Pinot Gris. Foods, 14(15), 2738. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14152738