Transitioning from a Multi-Agency to an Integrated Food Control System: A Case Study from the Sultanate of Oman

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Food Security and Sustainability in Oman

1.2. Regional and Global Interaction and Collaboration

2. Objectives

3. Review Methodology

- •

- ○

- Food control management;

- ○

- Food legislation;

- ○

- Food inspection and surveillance;

- ○

- Official food control laboratories;

- ○

- Food safety and quality information, education and communication.

- •

- The FAO/WHO Food Control System Assessment tool [1] was incorporated into the study to enhance the assessment, and to evaluate the newly integrated system in the country based on four dimensions, including inputs and resources, control functions, stakeholder interaction, science and knowledge, and continuous improvements.

- •

- The FAO/WHO Guide to Developing National Food Recall Systems [6] was used to assess Oman’s emergency response and food recall capabilities.

- •

- Official policy documents, legislation, government databases and reports. The search method included royal decrees, ministerial decisions, national strategy plans and internal regulatory reports and documents. These documents were collected through governmental portals, websites, official gazettes and legal databases.

- •

- Stakeholder semi-structured interviews: the interviews were carried out with key officials from various governmental authorities.

- •

- Peer-reviewed literature, academic journals, and relevant regional and international organization websites: a systematic search was conducted through Scopus, PubMed, Science Direct and Google Scholar and international sites (e.g., GCC, FAO, WHO, etc.). The literature was reviewed to identify, similar challenges, global best practices, advanced and relevant benchmarks for the Oman’s case.

4. An Overview of the Progress of the National Food Safety Management System in the Sultanate of Oman

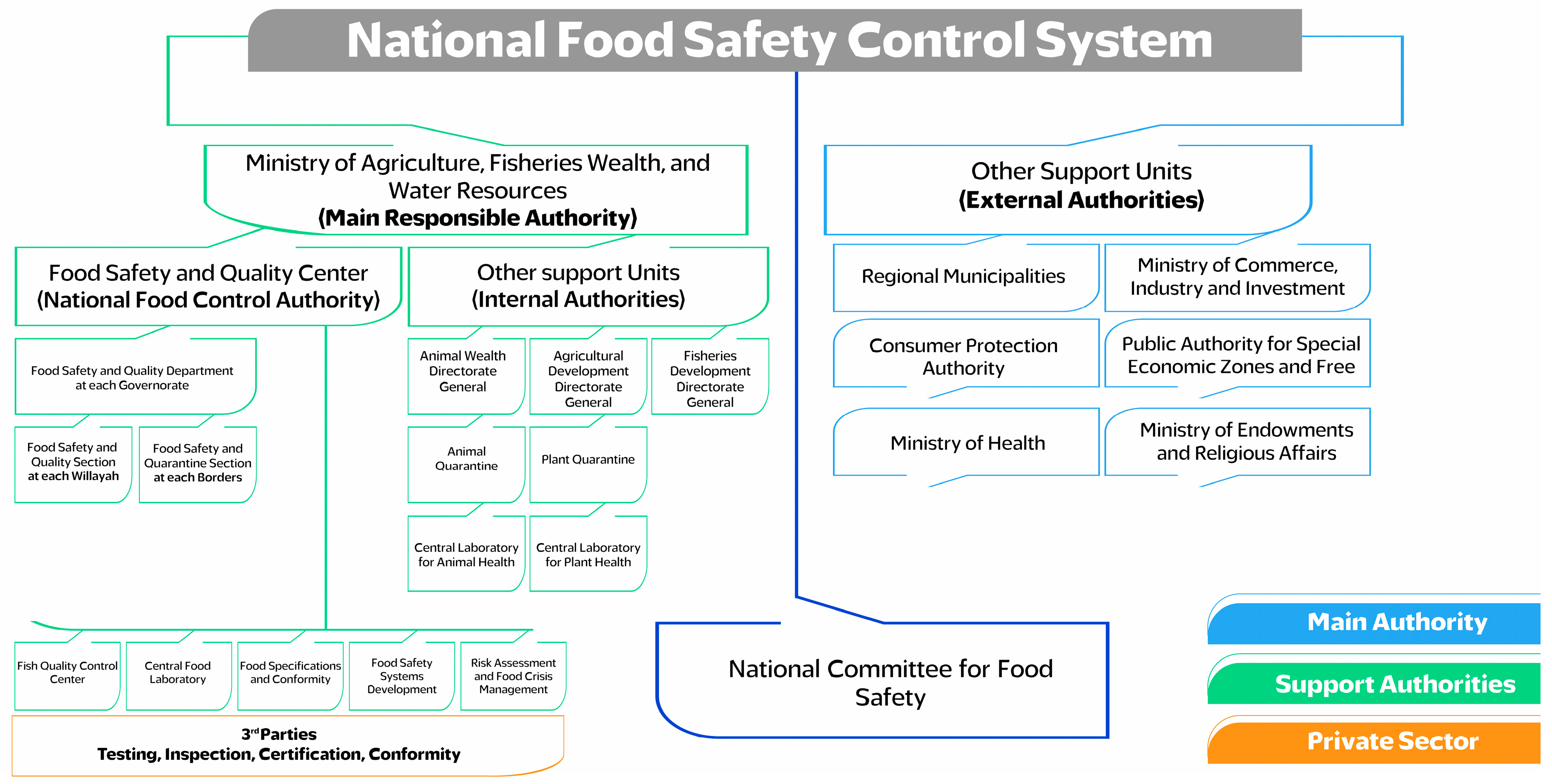

4.1. Food Control Management

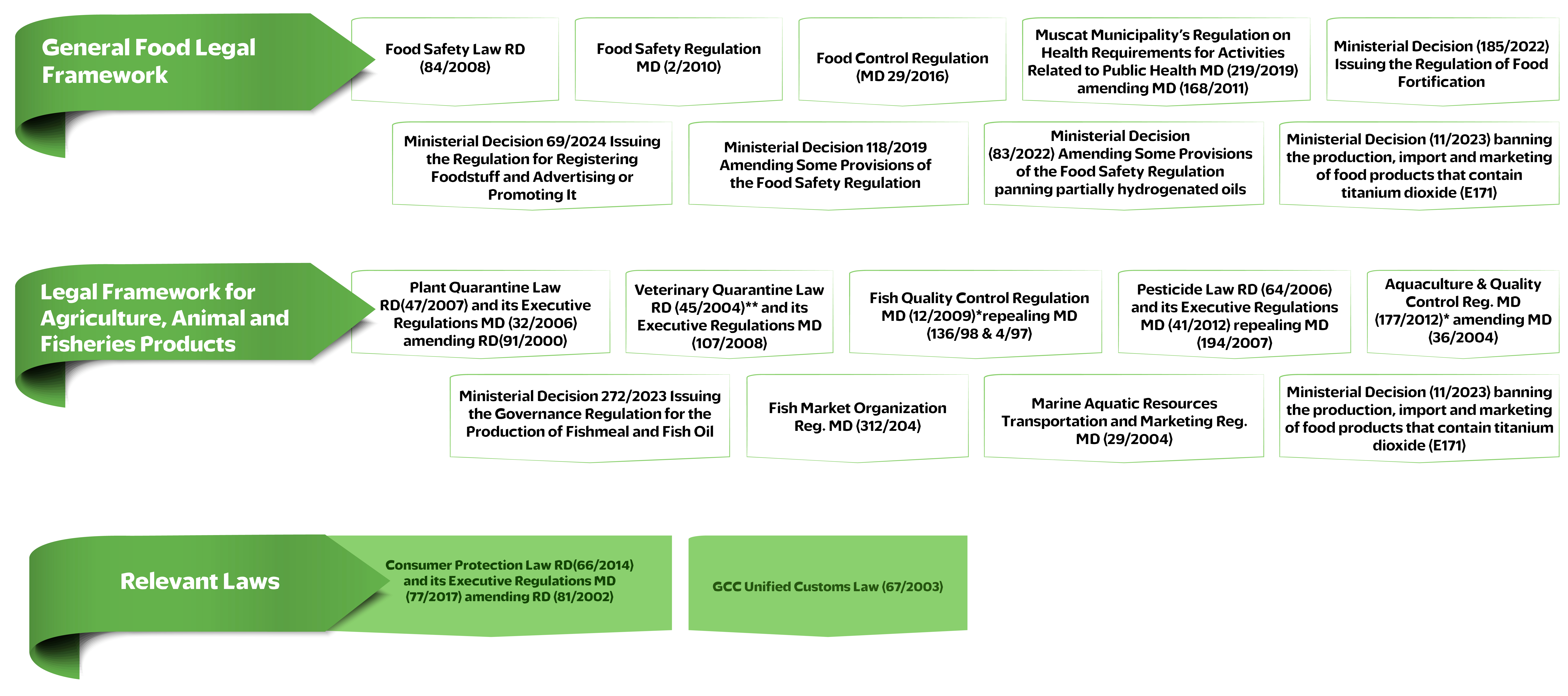

4.2. Legislative and Policy Frameworks

4.3. Food Monitoring and Surveillance

4.4. Inspection and Official Enforcement

4.4.1. Veterinary Quarantine

4.4.2. Plant Quarantine

4.4.3. Official Food Control Laboratories

4.4.4. Accreditation and Qualification of Food Facilities at Source (Domestic and International)

4.4.5. Logistics Stations or Hubs

4.4.6. Traceability

4.5. Management of Food Safety Emergencies and Crises

4.6. Public Awareness and Research Development

4.7. Achievements, Challenges and Future Directions of the National Food Control System

4.7.1. Achievements

4.7.2. Challenges

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GCC | Gulf Cooperation Council |

| CAC | Codex Alimentarius Commission |

| WOAH | World Organization for Animal Health |

| GSO | Gulf Standardization Organization |

| WTO | World Trade Organization |

| TBT | Technical Barriers to Trade Agreement |

| SPS | Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures Agreement |

| ROMPE | Regional Organization for the Protection of the Marine Environment |

| EU | European Union |

| IAEA | International Atomic Energy Agency |

| IPPC | International Plant Protection Convention |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| MAFWR | Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Water Resources |

| GRASFF | Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed |

| NFSC | National Food Safety Committee |

| FSQC | Food Safety and Quality Centre |

| MRMWR | Ministry of Regional Municipalities and Water Resources |

| MCIIP | Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Investment Promotion |

| OPAZ | Oman Public Authority for Special Economic Zones and Free Zones |

| FQDs | Food and Quarantine Departments |

| MOH | Ministry of Health |

| PACP | Public Authority for Consumer Protection |

| ROP | Royal Oman Police |

References

- FAO/WHO. Food Control System Assessment Tool: Dimension A—Inputs and Resources; Food Safety and Quality Series No. 7/2; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; WTO. Trade and Food Standards; Food and Agriculture Organization and World Trade Organization: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Strengthening National Food Control Systems Guidelines to Assess Capacity Building Needs; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- WHO. Risk-Based Food Inspection System: Practical Guidance for National Authorities; World Health Organization Western Pacific: Manila, Philippines, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- FAO/WHO. FAO/WHO Guide for Developing and Improving National Food Recall Systems; Food and Agriculture Organization/World Health Organization: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- FAO/WHO. Assuring Food Safety and Quality: Guidelines for Strengthening National Food Control Systems; Food and Nutrition Paper, 76; Food and Agricultural Organization/World Health Organization: Rome, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, H.V.; Dinh, T.L. The Vietnam’s food control system: Achievements and remaining issues. Food Control 2020, 108, 106862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.A.; Badrie, N.; Singh, M. The National Food Control System in Guyana: Evaluation of the Current Regulatory Framework for Food Control Systems. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Emerging Trends in Engineering and Technology (IConETech-2020), St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago, 1–5 June 2020; pp. 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, F.; Sonnino, R.; López Cifuentes, M. Connecting the dots: Integrating food policies towards food system transformation. Environ. Sci. Policy 2024, 156, 103735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MJLA. Royal Decree 24/2019 establishing the Centre for Food Safety and Quality in the Ministry of Regional Municipalities and Water Resources; Ministry of Regional Municipalities and Water Resources: Muscat, Oman, 2019.

- Faour-Klingbeil, D.; Al-Busaidi, M.A.; Todd, E.C.D. Legislation for food control in the Arab countries of the Middle East. In Food Safety in the Middle East; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 275–322. [Google Scholar]

- GFSI. Global Food Security Index; The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture; Food and Agricultural Organization: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vågsholm, I.; Arzoomand, N.S.; Boqvist, S. Food security, safety, and sustainability—Getting the Trade-Offs Right. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAFWR. Food Systems Report in the Sultanate of Oman: United Nations Food Systems Summit; Ministry of Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries Wealth, and Water Resources: Muscat, Oman, 2021.

- Oman Vision 2040. Implementation Follow-Up Unit; Its Priorities and Objectives: Muscat, Oman, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- MAFWR. Annual Report for 2023; Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries Wealth, and Water Resources: Muscat, Oman, 2023.

- MAFWR. Nazdaher Platform; Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries Wealth, and Water Resources: Muscat, Oman, 2024.

- GCC-STAT. Data Gateway Platform. Available online: https://gccstat.org/en/ (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- SG-GCC. Secretariat General of the Gulf Cooperation Council, the Customs Union. Available online: https://www.gcc-sg.org/en (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- GCC-SG. Standards Support the Economy, Improve Safety and Health, Use Our Global Resources More Efficiently and Improve Our Quality of Life. Available online: https://www.gso.org.sa/en/standards/ (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Al-Busaidi, M.A.A. Effective Seafood Safety and Quality Management Systems: An Analysis of the Situation in the Sultanate of Oman. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Reading, Reading, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf. FAOLEX Database. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faolex/ (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- GRASF. Saudi Food and Drug Authority (SFDA). Available online: https://grasf.sfda.gov.sa (accessed on 19 October 2024).

- Martin, T.; Dean, E.; Hardy, B.; Jhonson, T.; Jolly, F.; Mattews, F.; Mckay, I.; Souness, R.; Williams, J. A new era for food safety regulation in Australia. Food Control 2003, 14, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slorach, A.A. Integrated Approaches to the Management of Food Safety Throughout the Food Chain; FAO/WHO Global Forum of Food Safety Regulators: Marrakesh, Morocco, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ngqangashe, Y.; Friel, S. Regulatory governance pathways to improve the efficacy of Australian food policies. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2022, 46, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Busaidi, M.A.; Jukes, D.J. Assessment of the food control systems in the Sultanate of Oman. Food Control 2015, 51, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Busaidi, M.A.; Jukes, D.J.; Bose, S. Seafood safety and quality: An analysis of the supply chain in the Sultanate of Oman. Food Control 2016, 59, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Busaidi, M.A.; Jukes, D.J.; Bose, S. Hazard analysis and critical control point (HACCP) in seafood processing: An analysis of its application and use in regulation in the Sultanate of Oman. Food Control 2017, 73, 900–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Fishery and Aquaculture Country Profiles; Oman, 2013, Country Profile Fact Sheets; Fisheries and Aquaculture, Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Justice and Legal Affairs (MJLA). Basic Law of State. Sultanate of Oman. Available online: https://www.mjla.gov.om (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- Oxford Business Group. Summary of Relevant Laws and Regulations for Investors in Oman. Available online: https://oxfordbusinessgroup.com/ (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- FSQC. The Efforts of the Food Safety and Quality Center to Ensure the Safety of Food Products; Food Safety and Quality Center, Ministry of Agricultural, Fisheries, and Water Resources: Muscat, Oman, 2023.

- Candela, J.J.L.; Pereira, L. Towards integrated food policy: Main challenges and steps ahead. Environ. Sci. Policy 2017, 75, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 17025:2017; General Requirements for the Competence of Testing and Calibration Laboratories. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ISO/IEC 17011:2017; Conformity Assessment—Requirements for Accreditation Bodies Accrediting Conformity Assessment Bodies. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Neeliah, S.A.; Goburdhun, D.; Neeliah, H. Using a stakeholder analysis to assess the Mauritian food control system. Electron. J. Commun. Inform. Innov. Health 2008, 2, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinzler, M.; Gerlach, D.; Brunn, H. New border control system for food originating from third world countries. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2011, 23, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FSQC. To Accommodate Future Growth in Food Consumption and Exports of Fish and Agricultural Products, the Sohar Logistics City Has Been Launched. Annual Report 2023; Food safety and Quality Centre, Ministry of Agricultural, Fisheries, and Water Resources: Muscat, Oman, 2023.

- Oman Daily. Available online: https://www.omandaily.om/print-article?articleId=1123851 (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Codex Alimentarius Commission. Principles for Traceability/Product Tracing as a Tool Within a Food Inspection and Certification System (CAC/GL 60-2006); Codex Alimentarius Commission: Rome, Italy, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- FSQC. Director-General, Personal Communication; Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries Wealth, and Water Resources (MAFWR): Muscat, Oman, 2025.

- Al Mandhari, W.A.; Al Jufaili, S.; Al Busaidi, M.; Dutta, S. Seafood traceability system: A comprehensive assessment of seafood establishments in the Sultanate of Oman. Aquac. Fish. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO. FAO/WHO Guide for Application of Risk Analysis During Food Safety Emergencies; Food and Agriculture Organization/World Health Organization: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- FAO/WHO. Food Control System Assessment Tool: Dimension D—Science/Knowledge Base and Continuous Improvement; Food Safety and Quality Series No. 7/5; Food and Agriculture Organization/World Health Organization: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC). World Food Safety Day/The Day Becomes a “Food Safety Week” in Oman. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fao-who-codexalimentarius/news-and-events/news (accessed on 19 October 2024).

- Eruaga, M.A. Assessing the role of public education in enhancing food safety practices among consumers. Int. J. Sch. Res. Sci. Technol. 2024, 4, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sribuathong, S.; Trevanich, S. Role of research and development for food safety and food security in Thailand. J. Dev. Sustain. Agric. 2010, 5, 110–120. [Google Scholar]

- MoHERI. Guidelines of Strategic Research Projects Program (SRPP); Ministry of Higher Education, Research, and Innovation: Muscat, Oman, 2021.

- Agricultural and Fisheries Development Fund (AFDF). Available online: https://afdf.gov.om/about-the-fund (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- Alrobaish, W.S.; Vlerick, P.; Luning, P.A.; Jacxsens, L. Food safety governance in Saudi Arabia: Challenges in control of imported food. J. Food Sci. 2020, 86, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barinda, S.; Ayuningtyas, D. Assessing the food control system in Indonesia: A conceptual framework. Food Control 2020, 134, 108687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlander, A.; Zoellner, C. Artificial intelligence opportunities to improve food safety at retail. Food Prot. Trends 2020, 40, 272–278. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, L. IFST Technical Brief Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Food Safety; University of Lincoln: Lincoln, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- FSQC. Annual Report 2024; Food Safety and Quality Centre, Ministry of Agricultural, Fisheries, and Water Resources: Muscat, Oman, 2024.

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, L.; Zhang, L.; Raghavan, V.; Wang, J. A comprehensive review on novel synthetic foods: Potential risk factors, detection strategies, and processing technologies. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadar, C.G.; Fletcher, A.; Moreira, B.R.; Hine, D.; Yadav, S. Waste to protein: A systematic review of a century of advancement in microbial fermentation of agro-industrial byproducts. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Omani Food Safety Legislation | Description | Authorities Responsible of Issuance |

|---|---|---|

| Law | The legal foundation for any system or rules that regulate the conduct of a community, outlining mandates and responsibilities of enforcement and the powers of regulatory bodies, as well as penalties for non-compliance. | Royal Decree (RD) promulgated by the Sultan |

| Executive Regulation | Rules or directives issued by a government or regulatory authority to implement and enforce laws passed by the legislative body. | Ministerial Decision (MD) by Relevant Ministries |

| Regulation | Refers to a rule or directive created and enforced by a governmental authority to control or govern conduct within its jurisdiction. Includes specific regulations providing detailed requirements for food safety practices, including hygiene standards, labeling requirements, permissible limits for contaminants, etc. | |

| Decision | A formal conclusion or resolution made by an authority or governing body on a specific issue or case. | |

| Technical Regulation | Refers to a set of specific requirements, standards, procedures, product characteristics or their related processes and production methods and applicable administrative provisions, established by a regulatory authority, for which compliance is mandatory, to ensure safety, quality, and performance in various sectors, including food safety, manufacturing, and consumer products. | Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Investment Promotion and Gulf Standard Organization (GSO) |

| Standard Specification | National standards for food quality and safety are aligned with international benchmarks to ensure consistency and reliability. These standards cover aspects such as food additives, packaging materials, and nutritional information. |

| Components of Analyses | Pre-2020 (Multi-Agency) | Post-2020 (Integrated Food Control System) |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Administrative structure |

|

|

| Allocation of resources in terms of financial, human, equipment, information, etc. |

|

|

| Scientific principles and risk analysis approach |

|

|

| Food safety crisis response |

|

|

| Integrated food chain approach covering the entire farm to plate continuum |

|

|

| Involvement of the various stakeholders from farm to plate continuum in decision making process and flow of information |

|

|

| Active involvement in regional and international standard-setting bodies on issues related to food safety and quality |

|

|

| Surveillance of food-borne illnesses (microbial, chemical, allergen and etc.) from primary production to consumption |

|

|

| Existence of a national database that consolidates all data generated from enforcement and laboratory activities. |

|

|

| ||

| Ensure a high level of health protection and safeguard consumer interests |

|

|

| The roles and responsibilities of government authorities responsible for food control within the food safety control management systems along with the mechanisms and procedures for their interactions |

|

|

| Existence of an integrated and comprehensive legislation that covers the entire farm-to-table continuum |

|

|

| Technical regulations and standards are based on sound science and comply with Codex Alimentarius Commission (CAC) |

|

|

| Sanctions and penalties enforcement |

|

|

| Outlines clear provisions on the responsibility for food safety and quality lies with producers and processors |

|

|

| Provides clear provision for the approval, registration or licensing of food premises |

|

|

| Provides clear provisions on traceability and recall procedures in case of safety issues |

|

|

| Includes obligations ensuring that only safe and fairly presented foods are placed in the market |

|

|

| Recognized country’s international obligations particularly to trade |

|

|

| Legislation in line with international standard |

|

|

| Contains provisions for detailed enforcement procedures |

|

|

| ||

| Inspection based on risk analysis including sampling programs and techniques for domestically-produced, imported and exported food |

|

|

| Roles and responsibilities of the inspection activities are clearly defined |

|

|

| Inspection activities encompass the entire farm-to-table approach |

|

|

| Requirement for qualified and trained inspectors |

|

|

| Reputation and integrity of the inspectors |

|

|

| Number of official inspectors authorized to carry out the enforcement duties within the food safety control systems |

|

|

| Existence of Inspection Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs)/manuals |

|

|

| A comprehensive understanding of existing food laws and regulations |

|

|

| Development of digitalization and real-time monitoring |

|

|

| Presence of a national database that categorizes food premises based on the risk level of the produced food products |

|

|

| Access to logistics for conducting inspections including resources, facilities, transportation modes, inspection equipment and devices |

|

|

| Existence of records and documentation covering various aspects of inspection activities, such as consumer complaints, investigation and management of outbreaks of food-borne illnesses, respond to and manage food emergencies, etc. |

|

|

| Presence of a review and evaluation mechanism for the food inspection system |

|

|

| ||

| Adequate number and strategic placement of official food control laboratories to support the food control system |

|

|

| Presence of reference laboratories for contaminants and food-borne disease causative agents |

|

|

| Accreditation of official food control laboratories according to international standards |

|

|

| Qualified food analysts with appropriate training, experience and integrity |

|

|

| Adequate infrastructure, facilities, equipment, supplies, reference materials, and participation in inter-laboratory proficiency testing |

|

|

| Access to calibration and maintenance services for equipment and instruments |

|

|

| Analytical methods for analysis of various contaminants are validated |

|

|

| Presence of standard operating procedures (SOPs) for all analytical methods |

|

|

| Effective coordination and collaboration between official food control laboratories and the enforcement officials |

|

|

| Effective coordination and collaboration between official food control laboratories and the public health system for food-borne disease surveillance, as well as any other relevant laboratories |

|

|

| ||

| Presence of extension and developing programs for implementing information, education, and communication (IEC) activities |

|

|

| There is a policy in place for IEC regarding food safety and quality, targeting external audiences such as consumers, NGOs, the food industry, and others |

|

|

| Availability of sufficient financial resources, appropriate materials and equipment to carry out IEC activities |

|

|

| Sufficiently trained FSC staff to carry out IEC |

|

|

| A risk communication system in place to manage food crises and emergencies |

|

|

| Presence of dedicated research institutions or departments focused on food safety and quality |

|

|

| Investment in food safety research |

|

|

| Collaboration with academic and research institutions |

|

|

| Innovation in food safety practices |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al Busaidi, M.A.; Rahman, M.S.; Al Masroori, H.S. Transitioning from a Multi-Agency to an Integrated Food Control System: A Case Study from the Sultanate of Oman. Foods 2025, 14, 2618. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14152618

Al Busaidi MA, Rahman MS, Al Masroori HS. Transitioning from a Multi-Agency to an Integrated Food Control System: A Case Study from the Sultanate of Oman. Foods. 2025; 14(15):2618. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14152618

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl Busaidi, Moza Abdullah, Mohammad Shafiur Rahman, and Hussein Samh Al Masroori. 2025. "Transitioning from a Multi-Agency to an Integrated Food Control System: A Case Study from the Sultanate of Oman" Foods 14, no. 15: 2618. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14152618

APA StyleAl Busaidi, M. A., Rahman, M. S., & Al Masroori, H. S. (2025). Transitioning from a Multi-Agency to an Integrated Food Control System: A Case Study from the Sultanate of Oman. Foods, 14(15), 2618. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14152618