Applying Visual Storytelling in Food Marketing: The Effect of Graphic Storytelling on Narrative Transportation and Purchase Intention

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Graphic Storytelling, Narrative Transportation, and Purchase Intention

2.2. Cognitive Fluency

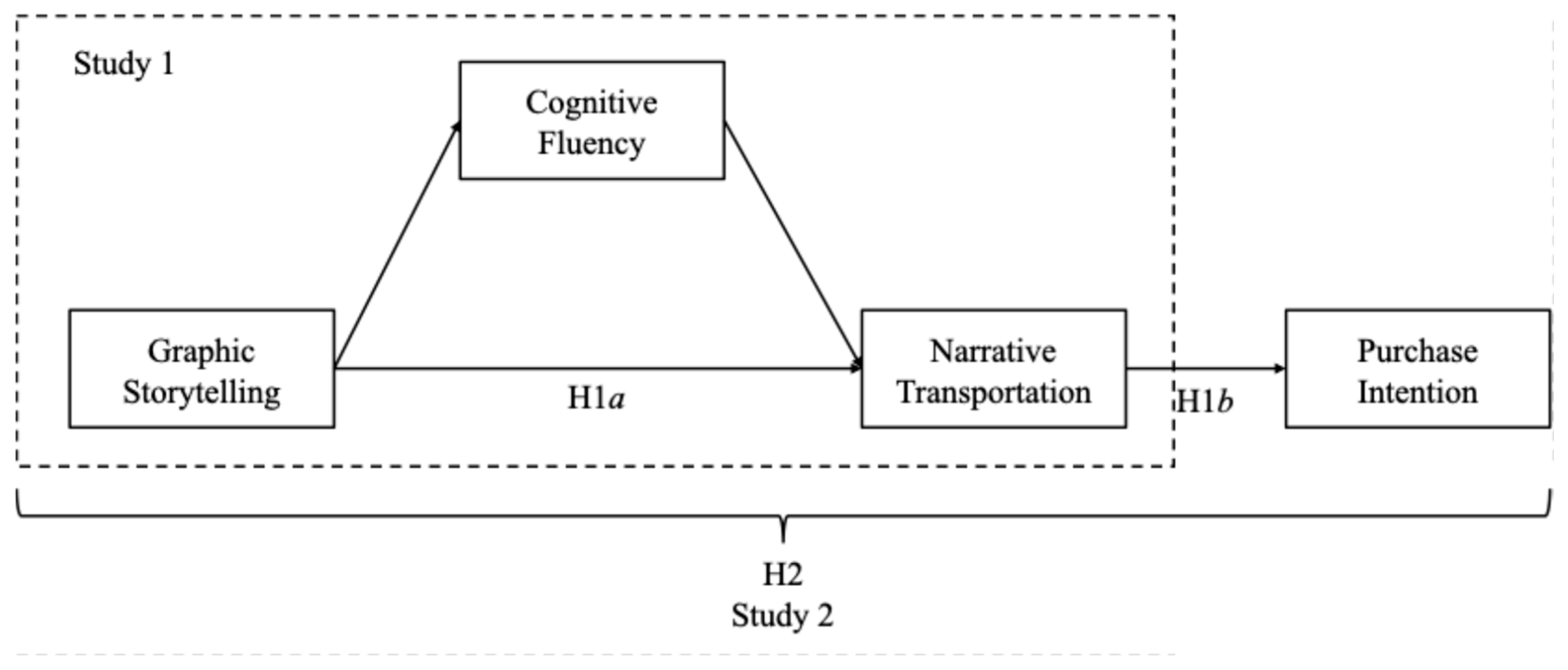

2.3. The Present Study

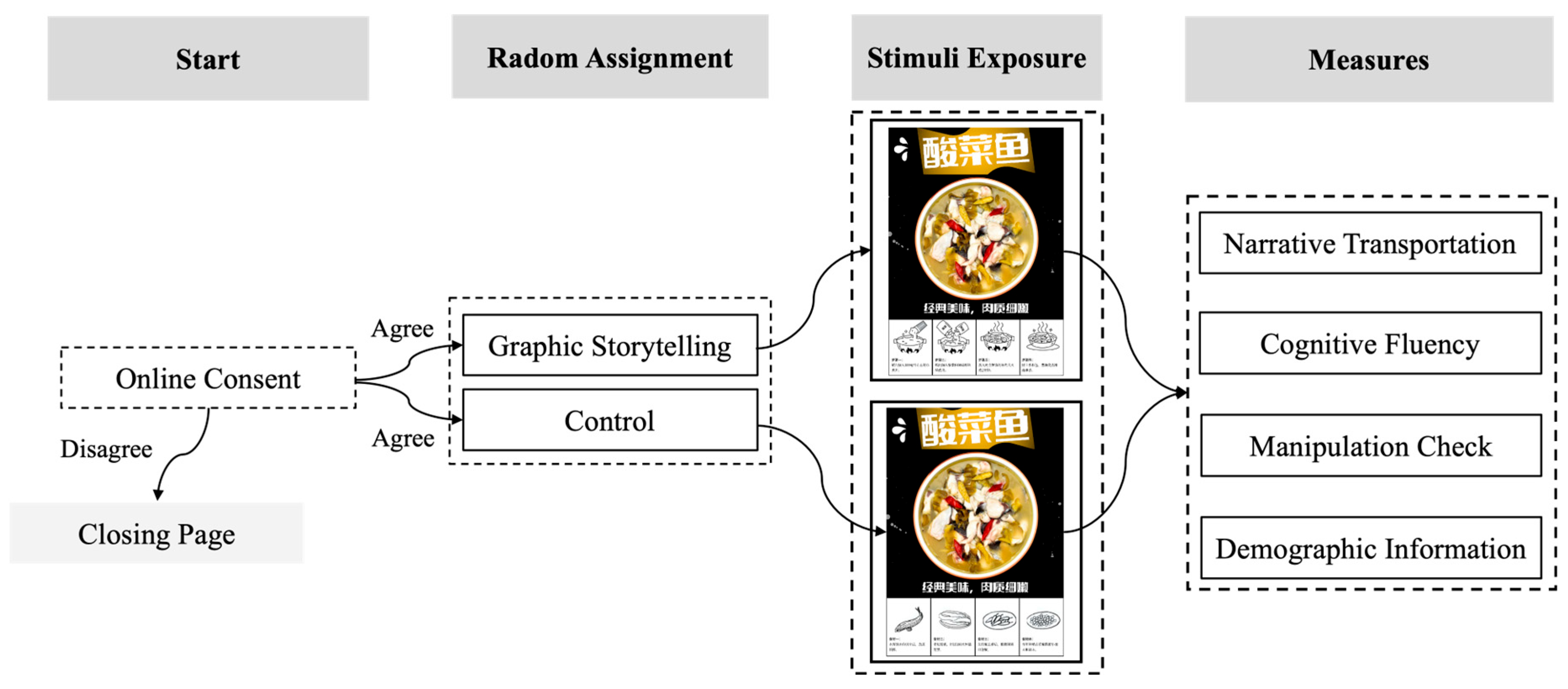

3. Study 1: Examining the Effect of Graphic Storytelling on Narrative Transportation and the Mediating Role of Cognitive Fluency

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Manipulation Check

3.4. Results

3.5. Discussion

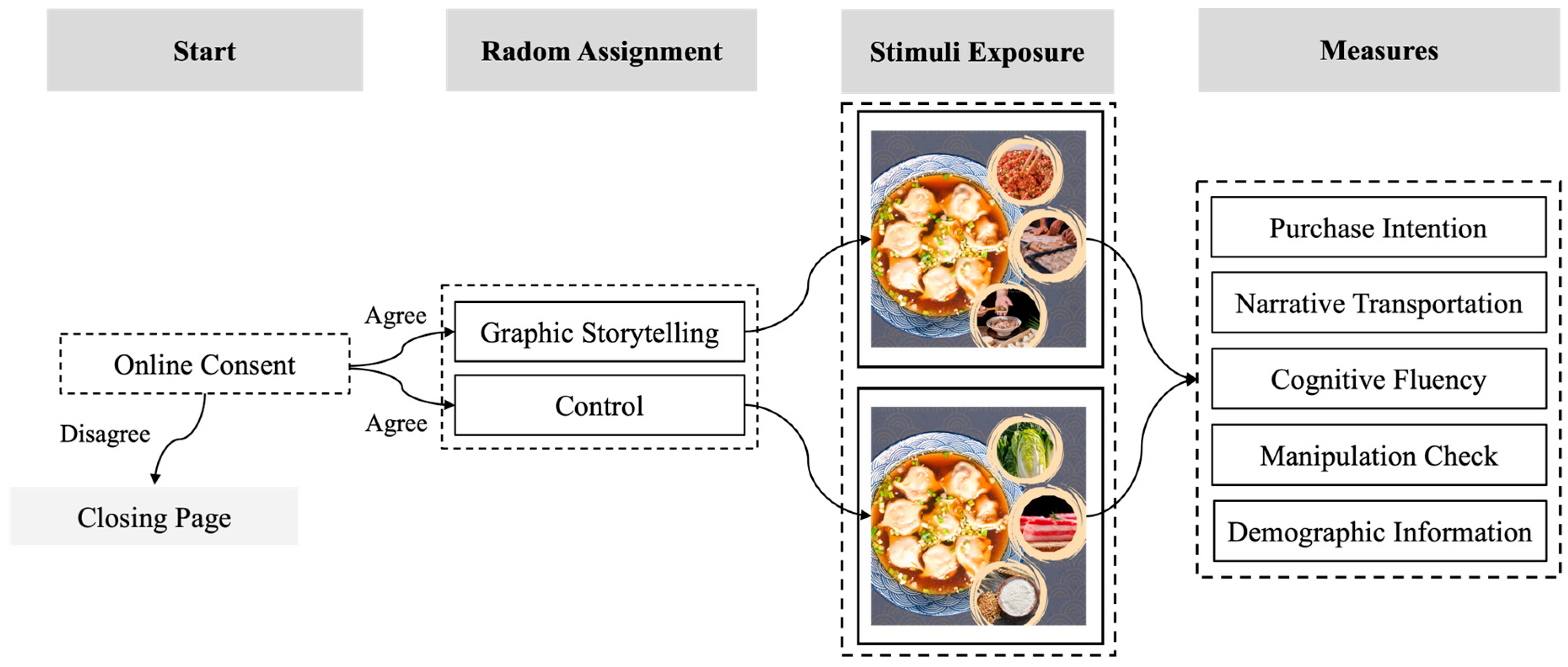

4. Study 2: The Effect of Graphic Storytelling on Narrative Transportation and Purchase Intention: The Mediating Role of Cognitive Fluency

4.1. Participants and Procedure

4.2. Measures

4.3. Manipulation Check

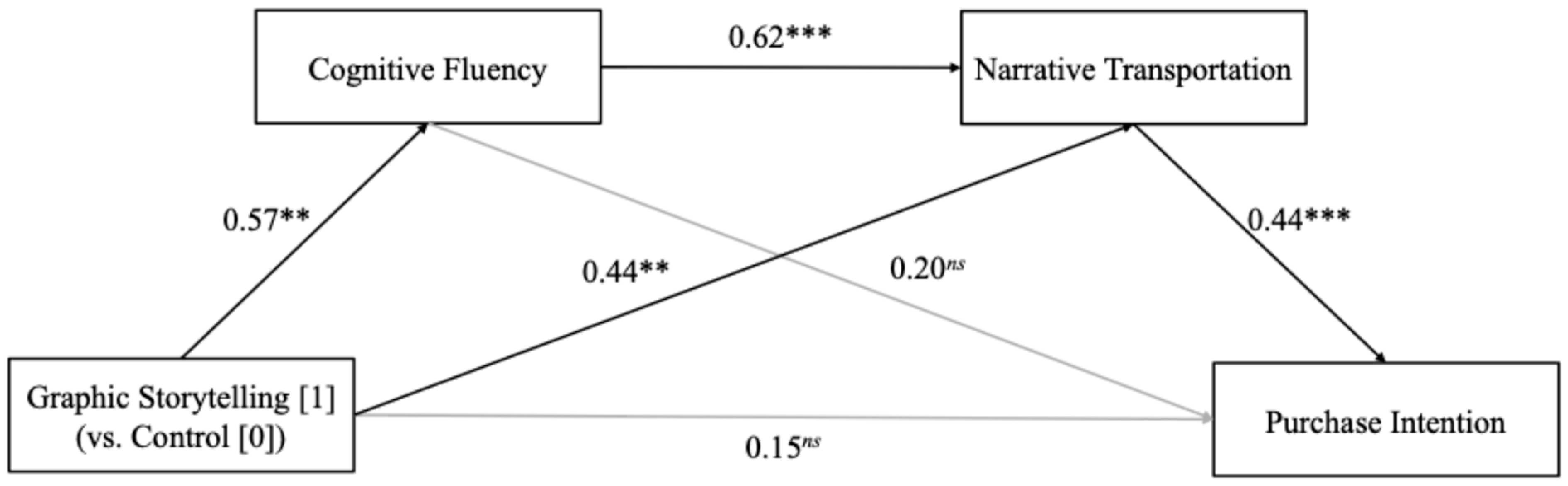

4.4. Results

4.5. Discussion

5. General Discussion

5.1. Findings

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Constructs | Items | Scale | Reliability | References |

| Cognitive fluency | 1. The process of understanding the packaging/ad was … | 1 = difficult ---- 5 = easy 1 = unclear ---- 5 = clear 1 = disfluent ---- 5 = fluent 1 = incomprehensible ---- 5 = comprehensible | 0.87 (Study 1) 0.79 (Study 2) | Graf, Mayer, and Landwehr [22] |

| 2. The process of understanding the packaging/ad was … | ||||

| 3. The process of understanding the packaging/ad was … | ||||

| 4. The process of understanding the packaging/ad was … | ||||

| Narrative transportation | 1. While viewing the packaging/ad, I could easily picture the event taking place. | 1 = strongly disagree 5 = strongly agree | 0.86 (Study 1) 0.85 (Study 2) | Green and Brock [36] |

| 2. While viewing the packaging/ad, I could imagine the dish preparation process in my mind. | ||||

| 3. I could picture myself in the scene depicted in the packaging/ad. | ||||

| 4. I was mentally involved in the narrative while viewing the packaging/ad. | ||||

| Purchase intention | 1. You are about to have lunch, how willing are you to consume the food. | 1 = strongly disagree 5 = strongly agree | 0.86 (Study 2) | Youn and Kim [53] |

| 2. You are about to have lunch, would you be willing to purchase the food. | ||||

| Manipulation check | 1. I think the packaging/ad shows the process of making the food. | 1 = strongly disagree 5 = strongly agree | 0.86 (Study 1) 0.94 (Study 2) | |

| 2. Through the packaging/ad, I saw the process of making the food. | ||||

| Attention check | 1. What are the steps/ingredients involved in making this food? |

References

- Zheng, L.; Miao, M.; Gan, Y. A systematic and meta-analytic review on the neural correlates of viewing high-and low-calorie foods among normal-weight adults. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 138, 104721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Zheng, L.; Xu, Y.; Wang, L. Food attention bias and Delboeuf illusion: Joint effect of calorie content and plate size on visual attention. Food Qual. Prefer. 2024, 120, 105261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, S.R.; Kozinets, R.V. The ethno/graphic novel: Alternative shapes of knowledge and hyper-intensity in consumer research. Consum. Mark. Cult. 2020, 23, 569–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megehee, C.M.; Woodside, A.G. Creating visual narrative art for decoding stories that consumers and brands tell. Psychol. Mark. 2010, 27, 603–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royo, M.; Chulvi, V.; Mulet, E.; Galán, J. Users’ reactions captured by means of an EEG headset on viewing the presentation of sustainable designs using verbal narrative. Eur. J. Mark. 2018, 52, 159–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C. “Being hooked” by editorial content: The implications for processing narrative advertising. J. Advert. 2009, 38, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, M.; Reisinger, H. Don’t lose your product in story translation: How product–story link in narrative advertisements increases persuasion. J. Advert. 2022, 51, 188–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, E.; Dost, F. Fluent contextual image backgrounds enhance mental imagery and evaluations of experience products. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 45, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topolinski, S.; Strack, F. Scanning the “Fringe” of consciousness: What is felt and what is not felt in intuitions about semantic coherence. Conscious. Cogn. 2009, 18, 608–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelley, B. Sequential art, graphic novels, and comics. SANE J. Seq. Art Narrat. Educ. 2010, 1, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Seifert, C.; Chattaraman, V. A picture is worth a thousand words! How visual storytelling transforms the aesthetic experience of novel designs. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2020, 29, 913–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalas, J.E. Narrative processing: Building consumer connections to brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2004, 14, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lien, N.-H.; Chen, Y.-L. Narrative ads: The effect of argument strength and story format. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Phelps, J.E.; Pimentel, D. Psychological transportation in narrative advertising. In Advertising Theory; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Van Laer, T.; De Ruyter, K.; Visconti, L.M.; Wetzels, M. The extended transportation-imagery model: A meta-analysis of the antecedents and consequences of consumers’ narrative transportation. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 40, 797–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, L. Do ads that tell a story always perform better? The role of character identification and character type in storytelling ads. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2018, 35, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikulina, O.; van Riel, A.C.; Lemmink, J.G.; Grewal, D.; Wetzels, M. Narrate, act, and resonate to tell a visual story: A systematic review of how images transport viewers. J. Advert. 2024, 53, 605–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appel, M.; Richter, T. Transportation and need for affect in narrative persuasion: A mediated moderation model. Media Psychol. 2010, 13, 101–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, C.; Appel, M.; Isberner, M.-B.; Richter, T. Argument strength and the persuasiveness of stories. Discourse Process. 2018, 55, 371–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringler, C.; Sirianni, N.J.; Peck, J.; Gustafsson, A. Does your demonstration tell the whole story? How a process mindset and social presence impact the effectiveness of product demonstrations. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2024, 52, 512–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J. If it is hard to understand, is it hard to be hooked? A meta-analysis of processing fluency and transportation. Int. J. Advert. 2025, 44, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, L.K.; Mayer, S.; Landwehr, J.R. Measuring processing fluency: One versus five items. J. Consum. Psychol. 2018, 28, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S. Consumer processing of mobile online stores: Sources and effects of processing fluency. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 36, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.M. The interplay of information order and locus of attention on the truth effect in healthy food advertisements. Psychol. Mark. 2024, 41, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostyk, A.; Leonhardt, J.M.; Niculescu, M. Simpler online ratings formats increase consumer trust. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2017, 11, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaud, D.A.; Melnyk, V. The effect of text-only versus text-and-image wine labels on liking, taste and purchase intentions. The mediating role of affective fluency. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 53, 101964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, R.E.; Lee, W.N. Communicating corporate social responsibility: How fit, specificity, and cognitive fluency drive consumer skepticism and response. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.; Auschaitrakul, S. Symbolic sequence effects on consumers’ judgments of truth for brand claims. J. Consum. Psychol. 2020, 30, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topolinski, S.; Strack, F. The architecture of intuition: Fluency and affect determine intuitive judgments of semantic and visual coherence and judgments of grammaticality in artificial grammar learning. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2009, 138, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dessart, L.; Pitardi, V. How stories generate consumer engagement: An exploratory study. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Lehto, X.Y.; Gordon, S.E.; Fu, X. Effect of a brand story structure on narrative transportation and perceived brand image of luxury hotels. Tour. Manag. 2019, 71, 348–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalas, J.E. Imagine yourself in the product: Mental simulation, narrative transportation, and persuasion. J. Advert. 2004, 33, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busselle, R.; Bilandzic, H. Measuring narrative engagement. Media Psychol. 2009, 12, 321–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, L.A.; Childs, K.E.; Maschinski, C.; Paul Niño, N.; Ellsworth, R. Regulatory fit, processing fluency, and narrative persuasion. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2010, 4, 1181–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megehee, C.M.; Spake, D.F. Consumer enactments of archetypes using luxury brands. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1434–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.C.; Brock, T.C. The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 701–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, P.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, X. Falling in love with a place because of a song: The transportation effects of music on place attachment. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 882–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leizerovici, G. Music and Auditory Transportation: An Investigation of the Music Experience. Ph.D. Thesis, Western University, London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cuny, C.; Fornerino, M.; Helme-Guizon, A. Can music improve e-behavioral intentions by enhancing consumers’ immersion and experience? Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T. The persuasive effectiveness of mini-films: Narrative transportation and fantasy proneness. J. Consum. Behav. 2015, 14, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, A.S.; Ekinci, Y.; Dilek-Fidler, S. Fantasy or reality? Unveiling the power of realistic narratives in tourism social media advertising. Tour. Manag. 2025, 106, 104998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ye, T.; Yu, C. Virtual voices in hospitality: Assessing narrative styles of digital influencers in hotel advertising. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 61, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruijn, M.; Bluijs, S. Unexpected Interactions: The Effect of Manipulation Figures on Narrative Engagement in Digital Literature. Master Thesis, Tilburg University, Tilburg, The Netherlands, 2021. Available online: https://arno.uvt.nl/show.cgi?fid=155358 (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Alekseeva, Y.; Garmaev, D.T.; Khoroshailo, T.; Martemyanova, A. Improvement of the technology for the production of semi-finished meat products. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Volgograd, Russian, 17–18 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jaud, D.A.; Braconnot, A.R.; Lunardo, R. Do stories (always) make food products taste better? The boundary effects of matching package type and product dimension. J. Consum. Behav. 2023, 22, 1224–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Effects of perceptual fluency on judgment and decision. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 18, 639–645. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, C.; Velasco, C. Digital Dining: New Innovations in Food and Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Velasco, C.; Spence, C. Multisensory Packaging: Designing New Product Experiences; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Motoki, K.; Takahashi, N.; Velasco, C.; Spence, C. Is classical music sweeter than jazz? Crossmodal influences of background music and taste/flavour on healthy and indulgent food preferences. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 96, 104380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Miao, M.; Zheng, L.; Wu, S.; Shi, S. Fit Effect of Health Regulatory Focus on Exercise and Healthy Diet: Asymmetric Moderating Role of Scarcity Mindset. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Luszczynska, A.; Miao, M.; Chen, Y.D.; Gan, Y.Q. Effects of environmental worry on fruit and vegetable intake. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2022, 29, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youn, H.; Kim, J.-H. Effects of ingredients, names and stories about food origins on perceived authenticity and purchase intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 63, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, L.; Fang, X.; Xiao, Y.; Li, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zheng, L.; Spence, C. Applying Visual Storytelling in Food Marketing: The Effect of Graphic Storytelling on Narrative Transportation and Purchase Intention. Foods 2025, 14, 2572. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14152572

Wang L, Fang X, Xiao Y, Li Y, Sun Y, Zheng L, Spence C. Applying Visual Storytelling in Food Marketing: The Effect of Graphic Storytelling on Narrative Transportation and Purchase Intention. Foods. 2025; 14(15):2572. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14152572

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Lingnuo, Xin Fang, Ying Xiao, Yangyue Li, Yulin Sun, Lei Zheng, and Charles Spence. 2025. "Applying Visual Storytelling in Food Marketing: The Effect of Graphic Storytelling on Narrative Transportation and Purchase Intention" Foods 14, no. 15: 2572. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14152572

APA StyleWang, L., Fang, X., Xiao, Y., Li, Y., Sun, Y., Zheng, L., & Spence, C. (2025). Applying Visual Storytelling in Food Marketing: The Effect of Graphic Storytelling on Narrative Transportation and Purchase Intention. Foods, 14(15), 2572. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14152572