Moringa oleifera Supplementation as a Natural Galactagogue: A Systematic Review on Its Role in Supporting Milk Volume and Prolactin Levels

Abstract

1. Introduction

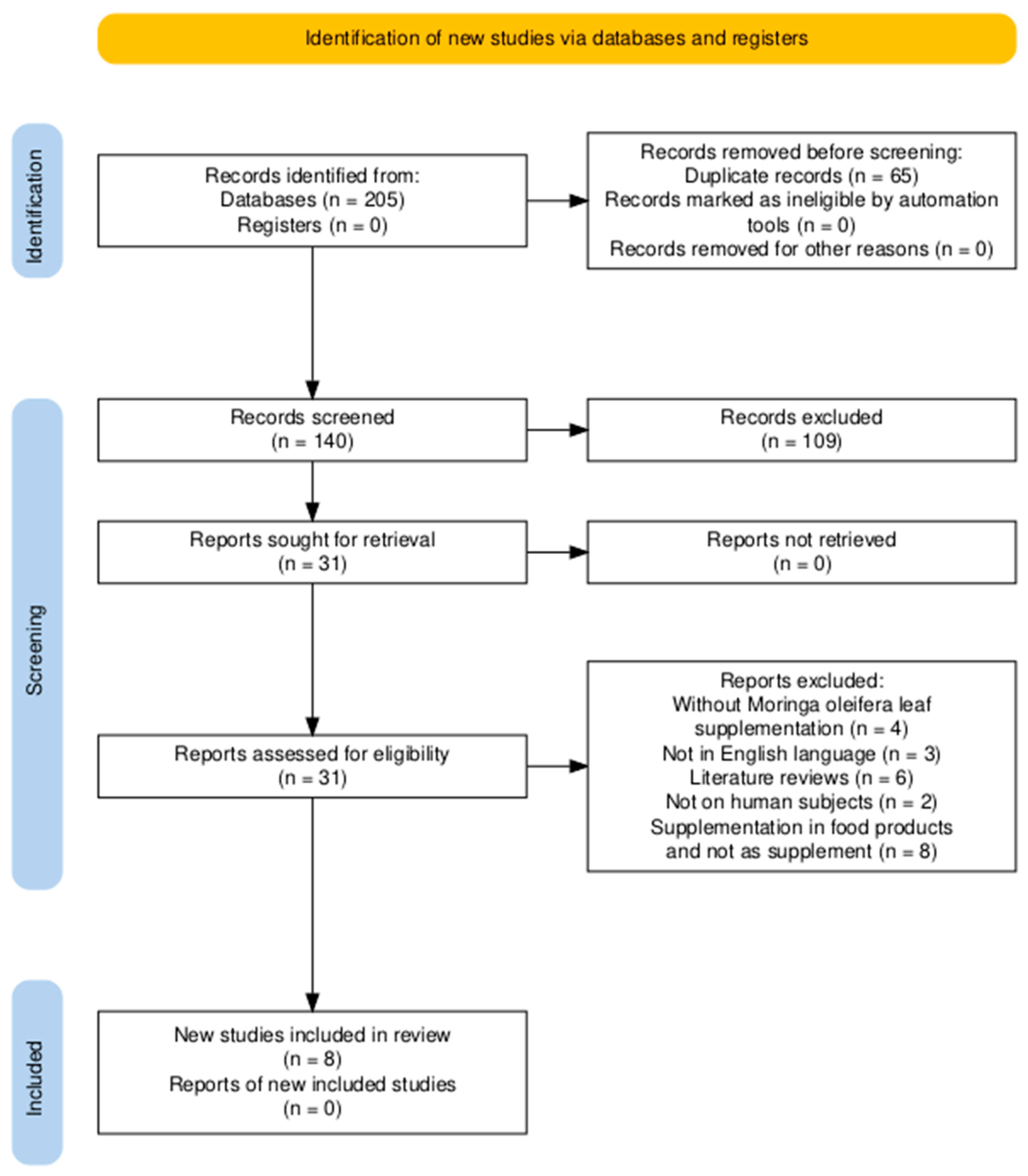

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Study Selection and Patient Population

2.3. Keywords Co-Occurrence Analysis

2.4. Eligibility Assessment and Data Extraction

2.5. Risk of Bias

3. Results

3.1. Description of Selected Trials

| Type of Study | Population | Intervention and Supplements | Procedure | Outcomes | Overall RoB | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretest and post-test group design | 20 postpartum mothers (age not reported). | 800 mg capsule, twice a day, for 1 month (ethanolic extract + Moringa powder, 1:4 ratio). | Taking the breast milk volume and after two treatments of acupressure and two capsules per day for 1 month visit in observation of breast milk volume. | Increase in breast milk volume (>400 mL/day). | Serious | [7] |

| Double-blind, randomized controlled trial. | 68 postpartum mothers (aged 20–45 years). | Capsule of 250 mg every 12 h from day 3 postpartum (commercial formulation). | Instructing mothers to use a standardized breast pump to pump their breasts every 4 h. The volume was measured with standardized containers and recorded in study logbook provided by the research team. | Increase in breast milk volume (152–176 mL/day). | Low | [24] |

| Single-blind Randomized Controlled Trial. | 82 postpartum mothers (aged 18–38 years). | 2 capsules of 350 mg/day from day 8 postpartum. | Milk collected using a breast pump. The expressed milk was immediately transferred to a standard container, and the amount of milk was recorded. | Augmentation of breast milk volume (up to 245 mL/day). | low | [34] |

| Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. | (88 postpartum mothers (>18 years old). | 1 capsule (450 mg), twice a day for 3 days (commercial leaf powder). | Taking the infant’s weight on the third postpartum day (48–72 h). The difference in weight in grams was then converted to the volume of breast milk in milliliters (1 g = 1 mL approximation). | 30% increase in breast milk volume (123.8 ± 84.9 mL/day). | Low | [35] |

| Quasi-Experimental study with Non Equivalent control group design | Breastfeeding postpartum mothers (30 postpartum mothers, aged 20–35 years). | 250 mg capsule, once daily 30 min before breastfeeding for 14 days. | Taking a blood sample for both groups, and measuring prolactin hormone levels by a Microplate Reader. | Increased level of prolactin hormones (231.72 ng/mL). | Some concern | [36] |

| Quasi-Experimental study with Non Equivalent control group design | 36 postpartum mothers (aged 27–30 years). | 250 mg capsule twice a day for 2 weeks (leaf powder capsules). | Measuring breast milk fat was done through laboratory measurments with the Soxhlet method, which is considered an indicator for increasing breast milk production. | Increased breast fat milk (from 4% to 4.5%) | Some concern | [37] |

| Quasi-experimental with pre/post-test control group design | Postpartum mothers, 7–10 days postpartum, exclusively breastfeeding. | Standardized Moringa oleifera extract tablets, 2 × 2 capsules/day for 30 days. | Infant weight was measured at baseline and at 30 days postpartum to assess breast milk adequacy indirectly. | Increased infant weight as a proxy for milk production. | Moderate | [38] |

| Quasi-experimental with combined intervention | 40 postpartum mothers, age not reported. | Moringa capsule 650 mg daily + acupressure for 10 days. | Prolactin measured via ELISA; infant weight monitored over 10 days. | Increased prolactin levels and infant weight. | Serious | [39] |

3.2. Database Analysis Results

3.3. Outcomes on the Milk Volume and Prolactin

3.4. Risk of Bias Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Future Perspectives

7. Limitations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCOS | Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome |

| PTPRF | Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase, Receptor type, F |

| PRL | Peptide hormone Prolactin |

| LTH | Luteotropin |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PICOs | Participants, Intervention, Comparators, Outcomes |

| RoB | Risk of Bias |

References

- Goksugur, S.B.; Karatas, Z. Breastfeeding and Galaktogogoneus Agents. Acta Med. Anatolia 2014, 2, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, P.D.; Aldag, J.C.; Demirtas, H.; Naeem, V.; Parker, N.P.; Zinaman, M.J.; Chatterton, R.T., Jr. Association of Serum Prolactin and Oxytocin with Milk Production in Mothers of Preterm and Term Infants. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2009, 10, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuppa, A.A.; Sindico, P.; Orchi, C.; Carducci, C.; Cardiello, V.; Catenazzi, P.; Romagnoli, C. Safety and efficacy of galacto-gogues: Substances that induce, maintain, and increase breast milk production. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 13, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBride, G.M.; Stevenson, R.; Zizzo, G.; Rumbold, A.R.; Amir, L.H.; Keir, A.K.; Grzeskowiak, L.E. Use and Experiences of Galactagogues While Breastfeeding Among Australian Women. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, J.; Raguindin, P.F.; Dans, L.F. Moringa oleifera (Malunggay) as a Galactagogue for Breastfeeding Mothers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Philipp. J. Pediatr. 2013, 61, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Egbuna, C. Moringa oleifera “The Mother’s Best Friend”. Int. J. Nutr. Food Sci. 2015, 4, 624–630. [Google Scholar]

- Renityas, N.N. The Effectiveness of Moringa Leaves Extract and Cancunpoint Massage towards Breast Milk Volume on Breastfeeding Mothers. J. Ners Kebidanan 2018, 5, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Abalaka, M.E.; Daniyan, S.Y.; Oyeleke, S.B.; Adeyemo, S.O. The antibacterial evaluation of Moringa oleifera leaf extracts on selected bacterial pathogens. J. Microbiol. Res. 2012, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barichella, M.; Pezzoli, G.; Faierman, S.A.; Raspini, B.; Rimoldi, M.; Cassani, E.; Cereda, E. Nutritional Characterisation of Zambian Moringa oleifera: Acceptability and Safety of Short-Term Daily Supplementation in a Group of Malnourished Girls. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 70, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oguntibeju, O.O.; Aboua, G.Y.; Omodanisi, E.I. Effects of Moringa oleifera on Oxidative Stress, Apoptotic, and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Animal Model. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 129, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimek-Szczykutowicz, M.; Gaweł-Bęben, K.; Rutka, A.; Blicharska, E.; Tatarczak-Michalewska, M.; Kulik-Siarek, K.; Szopa, A. Moringa oleifera (Drumstick Tree)—Nutraceutical, Cosmetological and Medicinal Importance: A Review. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1288382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Divya, S.; Pandey, V.K.; Dixit, R.; Rustagi, S.; Suthar, T.; Atuahene, D.; Shaikh, A.M. Exploring the Phytochemical, Pharmacological and Nutritional Properties of Moringa oleifera: A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raguindin, P.F.N.; Dans, L.F.; King, J.F. Moringa oleifera as a galactagogue. Breastfeed. Med. 2014, 9, 323–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasiri, K.; Heidari-Soureshjani, S.; Pocock, L. Medicinal plants’ effect on prolactin: A systematic review. Middle East J. Fam. Med. 2017, 7, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzano, A.N.; Hofer, R.; Thibeau, S.; Gillispie, V.; Jacobs, M.; Theall, K.P. A review of herbal and pharmaceutical galactagogues for breastfeeding. Ochsner J. 2016, 16, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Foong, S.C.; Tan, M.L.; Foong, W.C.; Marasco, L.A.; Ho, J.J.; Ong, J.H. Oral galactagogues (natural therapies or drugs) for increasing breast milk production in mothers of non-hospitalised term infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2020, CD011505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odom, E.C.; Li, R.; Scanlon, K.S.; Perrine, C.G.; Grummer-Strawn, L. Reasons for earlier than desired cessation of breastfeeding. Pediatrics 2013, 131, e726–e732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pareek, A.; Pant, M.; Gupta, M.M.; Kashania, P.; Ratan, Y.; Jain, V.; Chuturgoon, A.A. Moringa oleifera: An Updated Comprehensive Review of Its Pharmacological Activities, Ethnomedicinal, Phytopharmaceutical Formulation, Clinical, Phytochemical, and Toxicological Aspects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gatti, L. Maternal Perceptions of Insufficient Milk Supply in Breastfeeding. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2008, 40, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amir, L.H. Breastfeeding: Managing ‘Supply’ Difficulties. Aust. Fam. Physician 2006, 35, 686–689. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Neifert, M.; Bunik, M. Overcoming Clinical Barriers to Exclusive Breastfeeding. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 60, 115–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gianni, M.L.; Bettinelli, M.E.; Manfra, P.; Sorrentino, G.; Bezze, E.; Plevani, L.; Mosca, F. Breastfeeding Difficulties and Risk for Early Breastfeeding Cessation. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Fein, S.B.; Chen, J.; Grummer-Strawn, L.M. Why Mothers Stop Breastfeeding: Mothers’ Self-Reported Reasons for Stopping During the First Year. Pediatrics 2008, 122 (Suppl. S2), S69–S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrella, M.C.P.; Mantaring, J.B.V.; David, G.A. A Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial on the Use of Malunggay (Moringa oleifera) for Augmentation of the Volume of Breastmilk Among Non-Nursing Mothers of Preterm Infants. Philipp. J. Pediatr. 2000, 49, 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- El Sohaimy, S.A.; Hamad, G.M.; Mohamed, S.E.; Amar, M.H.; Al-Hindi, R.R. Biochemical and Functional Properties of Moringa oleifera Leaves and Their Potential as a Functional Food. Glob. Adv. Res. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 4, 188–199. [Google Scholar]

- Ziomkiewicz, A.; Babiszewska, M.; Apanasewicz, A.; Piosek, M.; Wychowaniec, P.; Cierniak, A.; Wichary, S. Psychosocial Stress and Cortisol Stress Reactivity Predict Breast Milk Composition. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemay, D.G.; Ballard, O.A.; Hughes, M.A.; Morrow, A.L.; Horseman, N.D.; Nommsen-Rivers, L.A. RNA Sequencing of the Human Milk Fat Layer Transcriptome Reveals Distinct Gene Expression Profiles at Three Stages of Lactation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berens, P.; Labbok, M.; Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. ABM Clinical Protocol #13: Contraception During Breastfeeding, Revised 2015. Breastfeed. Med. 2015, 10, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownell, E.A.; Fernandez, I.D.; Howard, C.R.; Fisher, S.G.; Ternullo, S.R.; Buckley, R.J.; Dozier, A.M. A Systematic Review of Early Postpartum Medroxyprogesterone Receipt and Early Breastfeeding Cessation: Evaluating the Methodological Rigor of the Evidence. Breastfeed. Med. 2012, 7, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoover, K.L.; Barbalinardo, L.H.; Platia, M.P. Delayed Lactogenesis II Secondary to Gestational Ovarian Theca Lutein Cysts in Two Normal Singleton Pregnancies. J. Hum. Lact. 2002, 18, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotella, R.; Soriano, J.M.; Llopis-González, A.; Morales-Suarez-Varela, M. The Impact of Moringa oleifera Supplementation on Anemia and Other Variables During Pregnancy and Breastfeeding: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A Revised Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinosa-Kuo, C.L. A Randomized Controlled Trial on the Use of Malunggay (Moringa oleifera) for Augmentation of the Volume of Breastmilk Among Mothers of Term Infants. Filip. Fam Physician 2005, 43, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Fungtammasan, S.; Phupong, V. The Effect of Moringa oleifera Capsule in Increasing Breast Milk Volume in Early Postpartum Patients: A Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. X 2022, 16, 100171. [Google Scholar]

- Sulistiawati, Y.; Suwondo, A.; Hardjanti, T.S.; Soejoenoes, A.; Anwar, M.C.; Susiloretni, K.A. Effect of Moringa oleifera on level of prolactin and breast milk production in postpartum mothers. Belitung Nurs. J. 2017, 3, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliastuti, S.; Kuntjoro, T.; Sumarni, S.; Supriyana, W.M. KELOR (Moringa oleifera) as an alternative in increasing breast milk production. J. Med. Sci. Clin. Res. 2018, 6, 1192–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiyanti, R.; Khuzaiyah, S.; Chabibah, N.; Khanifah, M. Effectiveness of Moringa oleifera Extract to Increase Breastmilk Production in Postpartum Mothers with Food Restriction. In Proceedings of the 1st Borobudur International Symposium on Humanities, Economics and Social Sciences (BIS-HESS 2019), Magelang, Indonesia, 16 October 2019; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2020; pp. 584–589. [Google Scholar]

- Wahidah, N.; Eko Ningtyas, E.A.; Latifah, L. Effect of the Combination of Acupressure and Moringa oleifera Extract Consumption on Elevating Breast Milk Production and Adequacy in Lactating Mothers. J. Matern. Child Health 2023, 8, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahaveerchand, H.; Abdul Salam, A.A. Environmental, Industrial, and Health Benefits of Moringa oleifera. Phytochem. Rev. 2024, 23, 1497–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Septadina, I.S.; Murti, K. Effects of Moringa Leaf Extract (Moringa oleifera) in Breastfeeding. Sriwijaya J. Med. 2018, 1, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsiami, A.S.; Puspariny, C. The Effectiveness of Moringa Leaf Jelly on Mother’s Prolactin Level and Baby’s Outcome. Int. J. Public Health Sci. 2024, 13, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurachma, E.; Lushinta, L.; Puspitaningsih, R.; Sholikah, I. The Effect of Moringa Pudding on Increasing Breast Milk for Postpartum Mothers. Asian J. Eng. Soc. Health 2024, 3, 1100–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, Z.; Nawawi, A.; Wibowo, A.; Nadhiroh, S.R.; Devy, S.R. Effects of Moringa oleifera on increasing breast milk in breastfeeding mothers with stunting toddlers in rural Batang-Batang District, Indonesia. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 2024, 28, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Breastfeeding postpartum mothers, healthy mothers, and healthy infants, do not take medication, on humans. | Non-breastfeeding mothers, pregnancy, mothers with chronic diseases, chorioamnionitis, taking any medication, mothers with breast anomalies, mothers of infants with neonatal illness and congenital anomalies and postpartum mothers with complications (bleeding infection), or experiments conducted on animals. Not exclusively breastfeeding. |

| Intervention | Capsules or tablets supplementation with Moringa powdered leaf extract. | No supplementation with Moringa leaf extract powdered capsules. |

| Control | Treatment (Moringa leaf extract), control (Placebo). | No comparison. |

| Outcome | Increases the volume of milk and prolactin. | Poor procedure or no clear findings. |

| Study design | Interventional trial (controlled randomized and uncontrolled (pre-test post-test). | Not related, no-clear finding. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ammar, M.; Russo, G.L.; Altamimi, A.; Altamimi, M.; Sabbah, M.; Al-Asmar, A.; Di Monaco, R. Moringa oleifera Supplementation as a Natural Galactagogue: A Systematic Review on Its Role in Supporting Milk Volume and Prolactin Levels. Foods 2025, 14, 2487. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14142487

Ammar M, Russo GL, Altamimi A, Altamimi M, Sabbah M, Al-Asmar A, Di Monaco R. Moringa oleifera Supplementation as a Natural Galactagogue: A Systematic Review on Its Role in Supporting Milk Volume and Prolactin Levels. Foods. 2025; 14(14):2487. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14142487

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmmar, Mohammad, Giovanni Luca Russo, Almothana Altamimi, Mohammad Altamimi, Mohammed Sabbah, Asmaa Al-Asmar, and Rossella Di Monaco. 2025. "Moringa oleifera Supplementation as a Natural Galactagogue: A Systematic Review on Its Role in Supporting Milk Volume and Prolactin Levels" Foods 14, no. 14: 2487. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14142487

APA StyleAmmar, M., Russo, G. L., Altamimi, A., Altamimi, M., Sabbah, M., Al-Asmar, A., & Di Monaco, R. (2025). Moringa oleifera Supplementation as a Natural Galactagogue: A Systematic Review on Its Role in Supporting Milk Volume and Prolactin Levels. Foods, 14(14), 2487. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14142487