Price Fairness, Consumer Attitude, and Loyalty in the U.S. Egg Market: The Moderating Roles of Tariff Concern and Education Level

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Review of the Literature and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Price Fairness

2.2. Attitude

2.3. Loyalty

2.4. Hypotheses Development

2.5. Moderating Roles of Tariff Concern and Education Level

3. Method

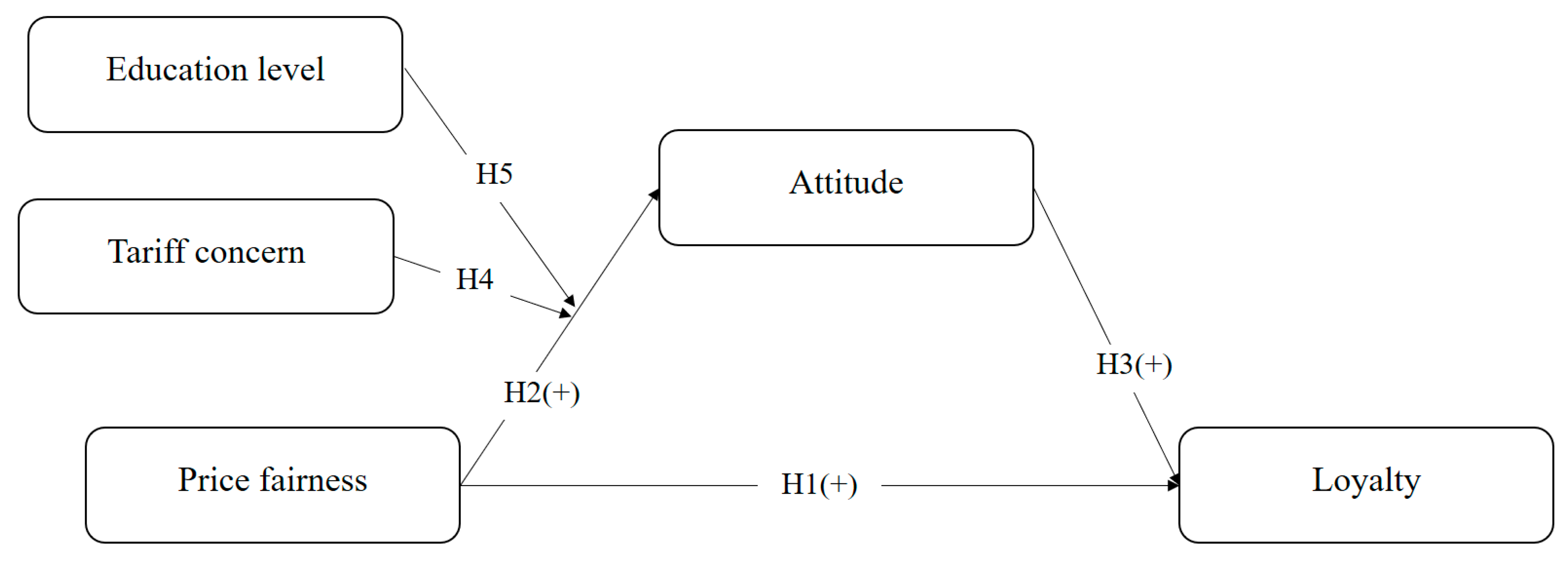

3.1. Research Model

3.2. Measurement Illustration

3.3. Data Analysis

3.4. Data Collection

4. Results of Empirical Analysis

4.1. Results of Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Convergent Validity

4.2. Correlation Matrix for Discriminant Validity

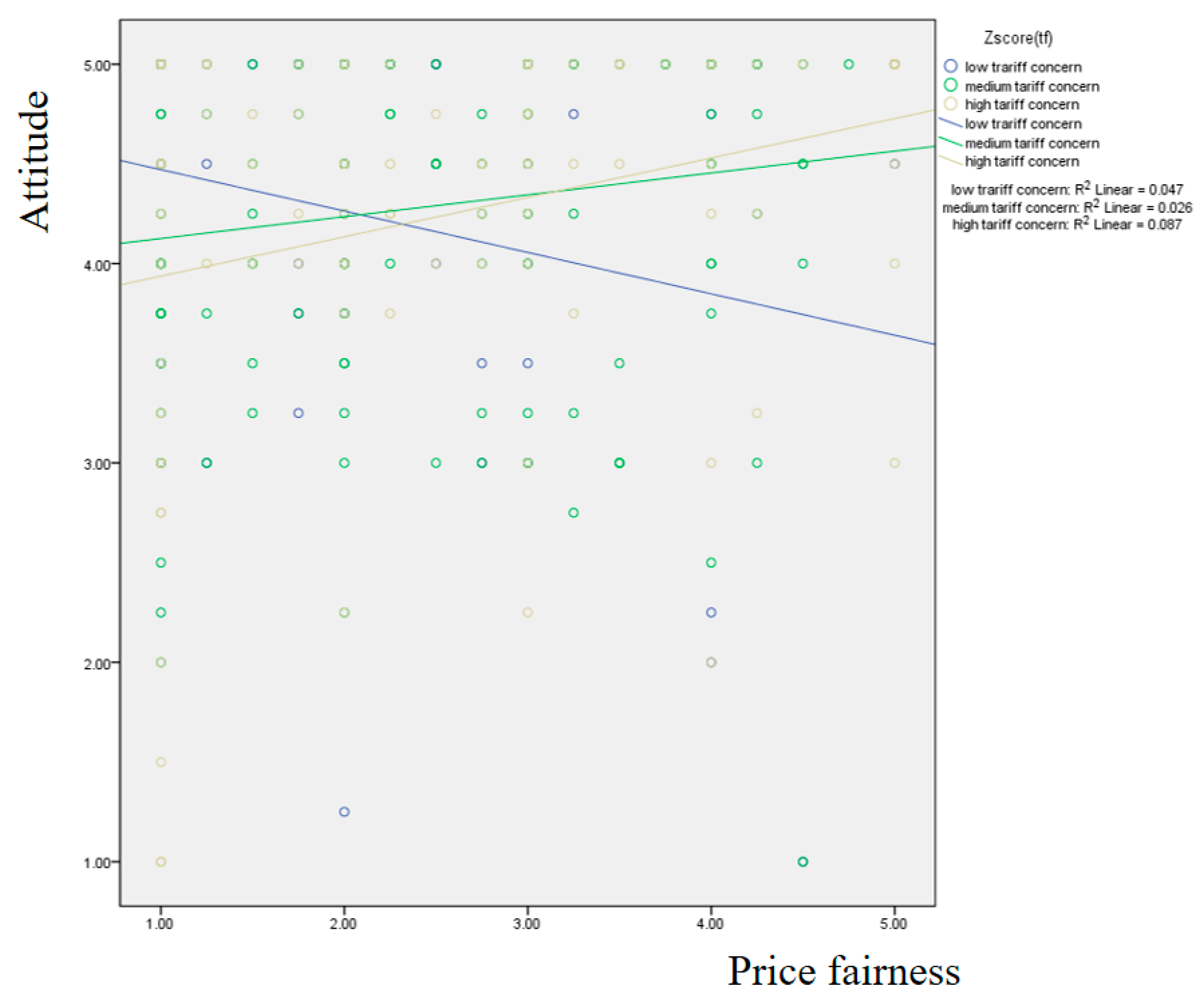

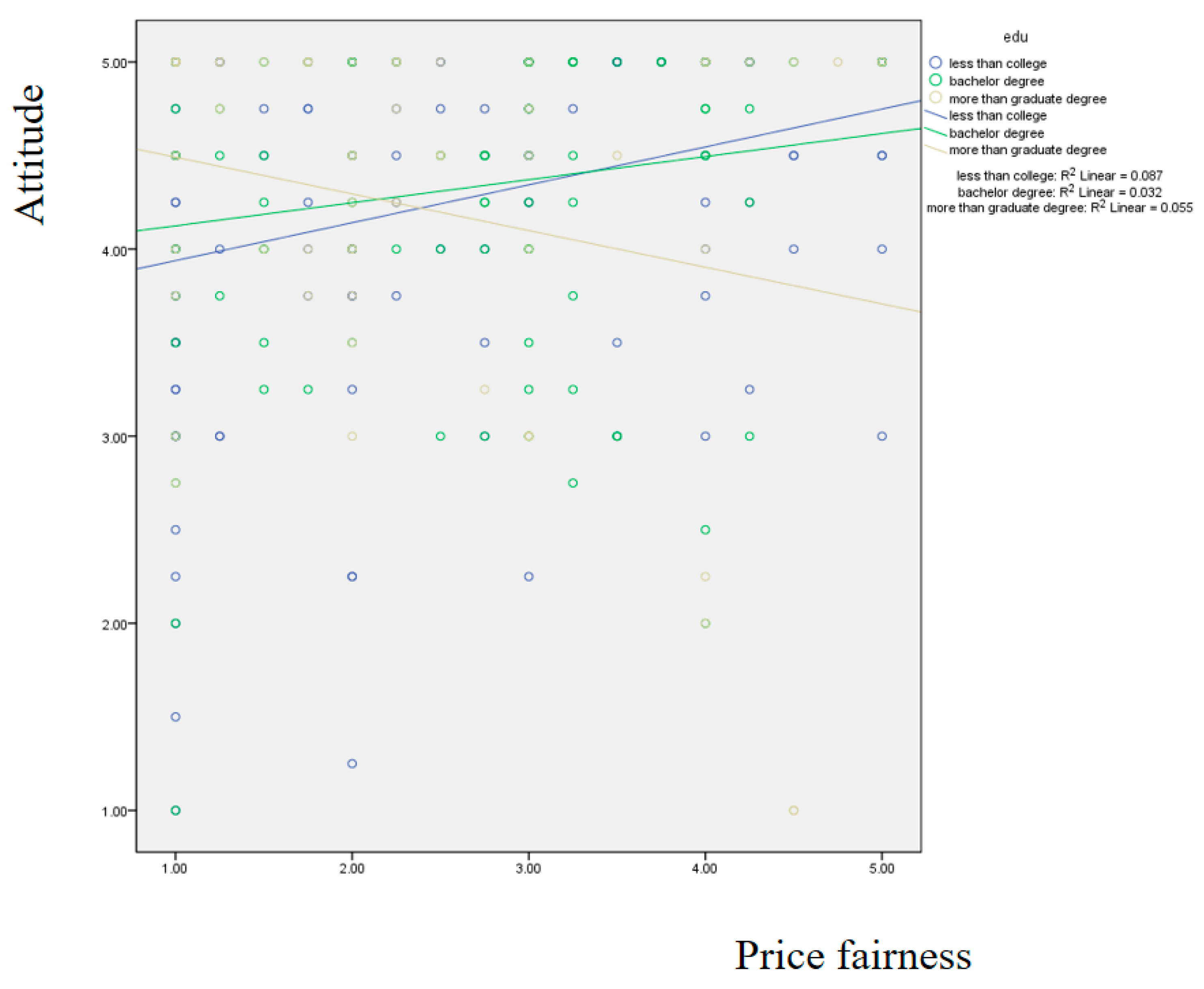

4.3. Results of Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fearne, A.; Lavelle, D. Segmenting the UK egg market: Results of a survey of consumer attitudes and perceptions. Br. Food J. 1996, 98, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, B.; Trinks, A.; Mörlein, D. Consumer preferences for the color of unprocessed animal foods. J. Food Sci. 2023, 88, 909–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rondoni, A.; Asioli, D.; Millan, E. Consumer behaviour, perceptions, and preferences towards eggs: A review of the literature and discussion of industry implications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 106, 391–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondoni, A.; Millan, E.; Asioli, D. Consumers’ preferences for intrinsic and extrinsic product attributes of plant-based eggs: An exploratory study in the United Kingdom and Italy. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 3704–3725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhou, L.; Höschle, L.; Yu, X. Food price dynamics and regional clusters: Machine learning analysis of egg prices in China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2023, 15, 416–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuhuan, W.; Fu, Q. Analysis of egg price fluctuation and cause. J. Agric. Sci. 2024, 10, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudiero, L.; Tak, M.; Alarcón, P.; Shankar, B. Understanding household and food system determinants of chicken and egg consumption in India. Food Secur. 2023, 15, 1231–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Liu, X.; Yao, L.; Liu, J. Consumer preferences and willingness to pay for eco-labelled eggs: A discrete choice experiment from Chongqing in China. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 1683–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Gao, L. Consumer attitude and behavioural intention towards organic wine: The roles of consumer values and involvement. Br. Food J. 2024, 126, 1743–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinho, V. Food and consumer attitude(s): An overview of the most relevant documents. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlas, A.; Valakosta, A.; Katsionis, C.; Oikonomou, A.; Brinia, V. The effect of corporate social responsibility on customer trust and loyalty. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, A.; Hong, Y.; Huang, K. Enhancing Brand Value Through Circular Economy Service Quality: The Mediating Roles of Customer Satisfaction, Brand Image, and Customer Loyalty. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaity, M.; Rahman, M. Customer loyalty towards Islamic banks: The mediating role of trust and attitude. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, K.; Fayyaz, M.; Shamim, A.; Abbasi, A.; Malik, S.; Abid, M. Attitude, repurchase intention and brand loyalty toward halal cosmetics. J. Islam. Mark. 2024, 15, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hsu, F.; Yan, L.; Lee, H.; Zhang, Y. Tourists’ food involvement, place attachment, and destination loyalty: The moderating role of lifestyle. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenneboer, L.; Herrando, C.; Constantinides, E. The impact of chatbots on customer loyalty: A systematic literature review. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2022, 17, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuters. US Egg Imports Meant to Drive Prices down Could Be Hit by Tariffs. 2025. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/world/us/us-egg-imports-meant-drive-prices-down-could-be-hit-by-tariffs-2025-04-03/ (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- USA Today. Trump’s New Tariffs Could Spike US Egg Prices Amid Supply Shortage. 2025. Available online: https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/economy/2025/04/03/egg-prices-shortage-trump-tariffs/82806047007/ (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Fortune. Trump Planned to Import Eggs to Lower Prices for Consumers. Then Came ‘Liberation Day’ Tariffs. 2025. Available online: https://fortune.com/2025/04/04/egg-prices-tariffs/ (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Guyonnet, V. World egg production and marketing trends. In Handbook of Egg Science and Technology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023; pp. 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kramskyi, S. Current trends and problems of the Ukrainian market of eggs & egg products in the conditions of uncertainty. Econ. Innov. 2022, 24, 100–109. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad, A.; Martinez, C.; Lawani, A. Why are eggs so expensive? Understanding the recent spike in egg prices. Choices 2023, 38, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, W.; Chi, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, V.; Xu, X. The influence of social education level on cybersecurity awareness and behaviour: A comparative study of university students and working graduates. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2023, 28, 439–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Wei, L. Explaining education-based difference in systematic processing of COVID-19 information: Insights into global recovery from infodemic. Inf. Process. Manag. 2022, 59, 102989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traore, O.; Doyon, M. Economic sustainability of extending lay cycle in the supply-managed Canadian egg industry. Front. Anim. Sci. 2023, 4, 1201771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, M.; Niessen, A.; Linde, M.; Tendeiro, J.; Meijer, R. “Adding an egg” in algorithmic decision making: Improving stakeholder and user perceptions, and predictive validity by enhancing autonomy. Eur. J. Work Org. Psychol. 2024, 33, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, Q.H.; Kim, T.Y.; Wang, X. Effects of logistics service quality and price fairness on customer repurchase intention: The moderating role of cross-border e-commerce experiences. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 70, 103165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konuk, F. Trustworthy brand signals, price fairness and organic food restaurant brand loyalty. Manag. Decis. 2023, 61, 3035–3052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hride, F.; Ferdousi, F.; Jasimuddin, S. Linking perceived price fairness, customer satisfaction, trust, and loyalty: A structural equation modeling of Facebook-based e-commerce in Bangladesh. Glob. Bus. Org. Excell. 2022, 41, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohaib, M.; Wang, Y.; Iqbal, K.; Han, H. Nature-based solutions, mental health, well-being, price fairness, attitude, loyalty, and evangelism for green brands in the hotel context. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 101, 103126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Slack, N.; Sharma, S.; Aiyub, A.; Ferraris, A. Antecedents and consequences of fast-food restaurant customers’ perception of price fairness. Br. Food J. 2022, 124, 2591–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halimi, F.; Gabarre, S.; Rahi, S.; Al-Gasawneh, J.; Ngah, A. Modelling Muslims’ revisit intention of non-halal certified restaurants in Malaysia. J. Islam. Mark. 2022, 13, 2437–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, P. Consumer attitude towards sustainability of fast fashion products in the UK. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaremohzzabieh, Z.; Ismail, N.; Ahrari, S.; Samah, A. The effects of consumer attitude on green purchase intention: A meta-analytic path analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 732–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvakirai, C.; Nalley, L.; Tshehla, M. What do we know about consumers’ attitudes towards cultured meat? A scoping review. Future Foods 2024, 9, 100279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymkowiak, A.; Antoniak, M.; Maślana, N. Changing consumer attitudes towards suboptimal foods: The effect of zero waste labeling. Food Qual. Pref. 2024, 114, 105095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Moon, J. The Theory of Planned Behavior and Antecedents of Attitude toward Bee Propolis Products Using a Structural Equation Model. Foods 2024, 13, 3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agha, A.; Rashid, A.; Rasheed, R.; Khan, S.; Khan, U. Antecedents of customer loyalty at telecomm sector. Turk. Online J. Qual. Inq. 2021, 12, 1352–1374. [Google Scholar]

- Shyu, C.; Yen, C.; Lin, C. The Impact of Consumer Loyalty and Customer Satisfaction in the New Agricultural Value Chain. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Moon, J. Assessing antecedents of restaurant’s brand trust and brand loyalty, and moderating role of food healthiness. Nutrients 2023, 15, 5057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; He, S.; Deng, H.; Wang, X. Sustaining customer loyalty of fresh food e-tailers: An empirical study in China. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2023, 35, 669–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Slack, N.; Sharma, S.; Mudaliar, K.; Narayan, S.; Kaur, R.; Sharma, K. Antecedents involved in developing fast-food restaurant customer loyalty. TQM J. 2021, 33, 1753–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbanee, F.; Afroz, T.; Naser, M. Are consumers loyal to genetically modified food? Evidence from Australia. Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 803–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, W.; Ponder, N.; Lueg, J. Price fairness perceptions and customer loyalty in a retail context. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 588–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prum, S.; Sovang, L.; Bunteng, L. Effects of Service Quality, Hotel Technology, and Price Fairness on Customer Loyalty mediated by Customer Satisfaction in Hotel Industry in Cambodia. Utsaha J. Entrep. 2024, 3, 12–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Park, S.; Kim, G. The effect of service price framing in an augmented product on price fairness, service and product attitude. J. Ind. Converg. 2021, 19, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Khandelwal, U.; Bajpai, N. Price fairness and its linear dependence on consumer attitude: A comparative study in metro and non metro city. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 4, 94–102. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, J.; Choe, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, J. Human baristas and robot baristas: How does brand experience affect brand satisfaction, brand attitude, brand attachment, and brand loyalty? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 99, 103050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacap, J.; Plaza, M.; Caballero, J.; dela Cruz, M. Factors affecting consumer attitude and loyalty: Evidence from a Philippine chain of fast-food restaurants’ smart retailing technology. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2024, 15, 1037–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hajiyev, N.; Smirnov, V. Tariff and non-tariff instruments of OPEC+ trade wars. Energy Strategy Rev. 2021, 38, 100771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benguria, F.; Choi, J.; Swenson, D.L.; Xu, M. Anxiety or pain? The impact of tariffs and uncertainty on Chinese firms in the trade war. J. Int. Econ. 2022, 137, 103608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausing, K.; Obstfeld, M. Letter from America: Trump’s 2025 tariff threats. Intereconomics 2024, 59, 243–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chor, D.; Li, B. Illuminating the effects of the US-China tariff war on China’s economy. J. Int. Econ. 2024, 150, 103926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya, Ó.; De La Vega, I. Drivers of the sharing economy that affect consumers’ usage behavior: Moderation of perceived risk. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Liu, F.; Liu, W.; Liu, S.; Chen, Y.; Xu, D. Effects of information quality on information adoption on social media review platforms: Moderating role of perceived risk. Data Sci. Manag. 2021, 1, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinsle, P.; Totzek, D.; Schumann, J. How price fairness and fit affect customer tariff evaluations. J. Serv. Manag. 2018, 29, 735–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goettler, R.; Clay, K. Tariff choice with consumer learning and switching costs. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 48, 633–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerosa, T.; Gui, M.; Hargittai, E.; Nguyen, M. (Mis) informed during COVID-19: How education level and information sources contribute to knowledge gaps. Int. J. Commun. 2021, 15, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Deming, D.J. Four facts about human capital. J. Econ. Perspect. 2022, 36, 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempen, G.; Brilman, E.; Ranchor, A.; Ormel, J. Morbidity and quality of life and the moderating effects of level of education in the elderly. Soc. Sci. Med. 1999, 49, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rammstedt, B.; Rammsayer, T. Self-estimated intelligence: Gender differences, relationship to psychometric intelligence and moderating effects of level of education. Eur. Psychol. 2002, 7, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, D.; Joshi, H. The moderating effect of demographic variables on mobile banking adoption: An empirical investigation. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2018, 19, S90–S113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyle, R. Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Anderson, R.; Babin, B.; Black, W. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. PROCESS: A Versatile Computational Tool for Observed Variable Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Modeling. 2012. Available online: http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2025).

- Hayes, A. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, A.; Ihl, A.; Grabl, S.; Strunk, K.; Fiedler, M. A silver lining for the excluded: Exploring experiences that micro-task crowdsourcing affords workers with impaired work access. Inf. Syst. J. 2024, 34, 1838–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muldoon, J.; Apostolidis, P. ‘Neither work nor leisure’: Motivations of microworkers in the United Kingdom on three digital platforms. New Media Soc. 2025, 27, 747–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anıl Konuk, F. Trust transfer, price fairness and brand loyalty: The moderating influence of private label product type. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2022, 50, 658–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Attribute | Code | Measurement Item | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Price fairness | PF1 | Egg prices were fair. | Konuk [28] Hride et al. [29] |

| PF2 | Egg prices were reasonable. | ||

| PF3 | Egg prices were appropriate. | ||

| PF4 | Egg prices were acceptable. | ||

| Attitude | AT1 | For me, the egg is (negative–positive) | Hussain et al. [14] Sun & Moon [37] |

| AT2 | For me, the egg is (bad–good) | ||

| AT3 | For me, the egg is (useless–useful) | ||

| AT4 | For me, the egg is (unfavorable–favorable) | ||

| Loyalty | LY1 | I am going to use the same eggs again. | Chen et al. [15] Hwang et al. [48] |

| LY2 | I will purchase the same eggs. | ||

| LY3 | I am willing to pay for the same eggs. | ||

| LY4 | I am willing to buy the same eggs. | ||

| Tariff concern | TF1 | Tariffs will cause economic anxiety. | Developed through consulting |

| TF2 | Tariffs will increase economic uncertainty. | ||

| TF3 | Tariffs will destabilize the economy. | ||

| TF4 | Tariffs will make the economic situation unpredictable. |

| Item | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 93 | 29.9 |

| Female | 218 | 70.1 |

| 20s | 40 | 12.9 |

| 30s | 119 | 38.3 |

| 40s | 103 | 33.1 |

| 50s | 38 | 12.2 |

| Older than 60 | 11 | 3.5 |

| Monthly household income | ||

| Under USD 2500 | 91 | 29.3 |

| USD 2500 and USD 4999 | 105 | 33.8 |

| USD 5000 and USD 7499 | 35 | 11.3 |

| USD 7500 and USD 9999 | 22 | 7.1 |

| Over USD 10,000 | 58 | 18.6 |

| Education level | ||

| Less than college | 138 | 44.4 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 115 | 37.0 |

| More than a graduate degree | 58 | 18.6 |

| Weekly consumption amount of eggs | ||

| Less than 1 egg | 40 | 12.9 |

| 2~4 eggs | 182 | 58.5 |

| 5~8 eggs | 68 | 21.9 |

| More than 9 eggs | 21 | 6.8 |

| Construct | Code | Loading | Mean (SD) | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Price fairness | PF1 | 0.893 | 2.53 (1.24) | 0.957 | 0.849 |

| PF2 | 0.965 | ||||

| PF3 | 0.923 | ||||

| PF4 | 0.903 | ||||

| Attitude | AT1 | 0.815 | 4.26 (0.88) | 0.893 | 0.676 |

| AT2 | 0.897 | ||||

| AT3 | 0.758 | ||||

| AT4 | 0.815 | ||||

| Loyalty | LY1 | 0.693 | 3.92 (0.97) | 0.895 | 0.683 |

| LY2 | 0.823 | ||||

| LY3 | 0.837 | ||||

| LY4 | 0.936 | ||||

| Tariff concern | TF1 | 0.846 | 3.92 (1.05) | 0.940 | 0.796 |

| TF2 | 0.909 | ||||

| TF3 | 0.897 | ||||

| TF4 | 0.917 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Loyalty | 0.826 | |||

| 2. Attitude | 0.396 * | 0.822 | ||

| 3. Price fairness | 0.189 * | 0.152 * | 0.921 | |

| 4. Tariff concern | −0.056 | 0.037 | 0.130 * | 0.892 |

| Model 1 Attitude | Model 2 Attitude | Model 3 Loyalty | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t Value | β | t Value | β | t Value | |

| Constant | 4.888 | 11.72 * | 3.262 | 12.00 * | 1.912 | 7.48 * |

| Price fairness | −0.304 | −1.88 | 0.403 | 4.12 * | 0.103 | 2.52 * |

| Tariff concern | −0.224 | −2.18 * | ||||

| Education level | 0.432 | 2.96 * | ||||

| Price fairness × Tariff concern | 0.101 | 2.62 * | ||||

| Price fairness × Education level | −0.174 | −3.30 * | ||||

| Attitude | 0.410 | 7.16 * | ||||

| F value | 4.81 * | 6.14 * | 334.89 * | |||

| R2 | 0.0449 | 0.0566 | 0.6843 | |||

| Conditional effect of focal predictor | ||||||

| Tariff concern | ||||||

| 3.00 | 0.009 | 0.01 | ||||

| 4.00 | 0.102 | 2.55 * | ||||

| 5.00 | 0.204 | 3.73 * | ||||

| Education level | ||||||

| 1.00 | 0.229 | 4.25 * | ||||

| 2.00 | 0.054 | 1.28 | ||||

| 3.00 | −0.119 | −1.50 | ||||

| Index of mediated moderation | Index | LLCI ULCI | Index | LLCI ULCI | ||

| 0.041 * | 0.0059 0.0834 | −0.071 * | −0.128 −0.019 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, M.G.; Moon, J. Price Fairness, Consumer Attitude, and Loyalty in the U.S. Egg Market: The Moderating Roles of Tariff Concern and Education Level. Foods 2025, 14, 2243. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14132243

Kim MG, Moon J. Price Fairness, Consumer Attitude, and Loyalty in the U.S. Egg Market: The Moderating Roles of Tariff Concern and Education Level. Foods. 2025; 14(13):2243. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14132243

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Min Gyung, and Joonho Moon. 2025. "Price Fairness, Consumer Attitude, and Loyalty in the U.S. Egg Market: The Moderating Roles of Tariff Concern and Education Level" Foods 14, no. 13: 2243. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14132243

APA StyleKim, M. G., & Moon, J. (2025). Price Fairness, Consumer Attitude, and Loyalty in the U.S. Egg Market: The Moderating Roles of Tariff Concern and Education Level. Foods, 14(13), 2243. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14132243