Health, Environment or Taste? Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Predict Plant-Based Milk Consumption

Abstract

1. Introduction

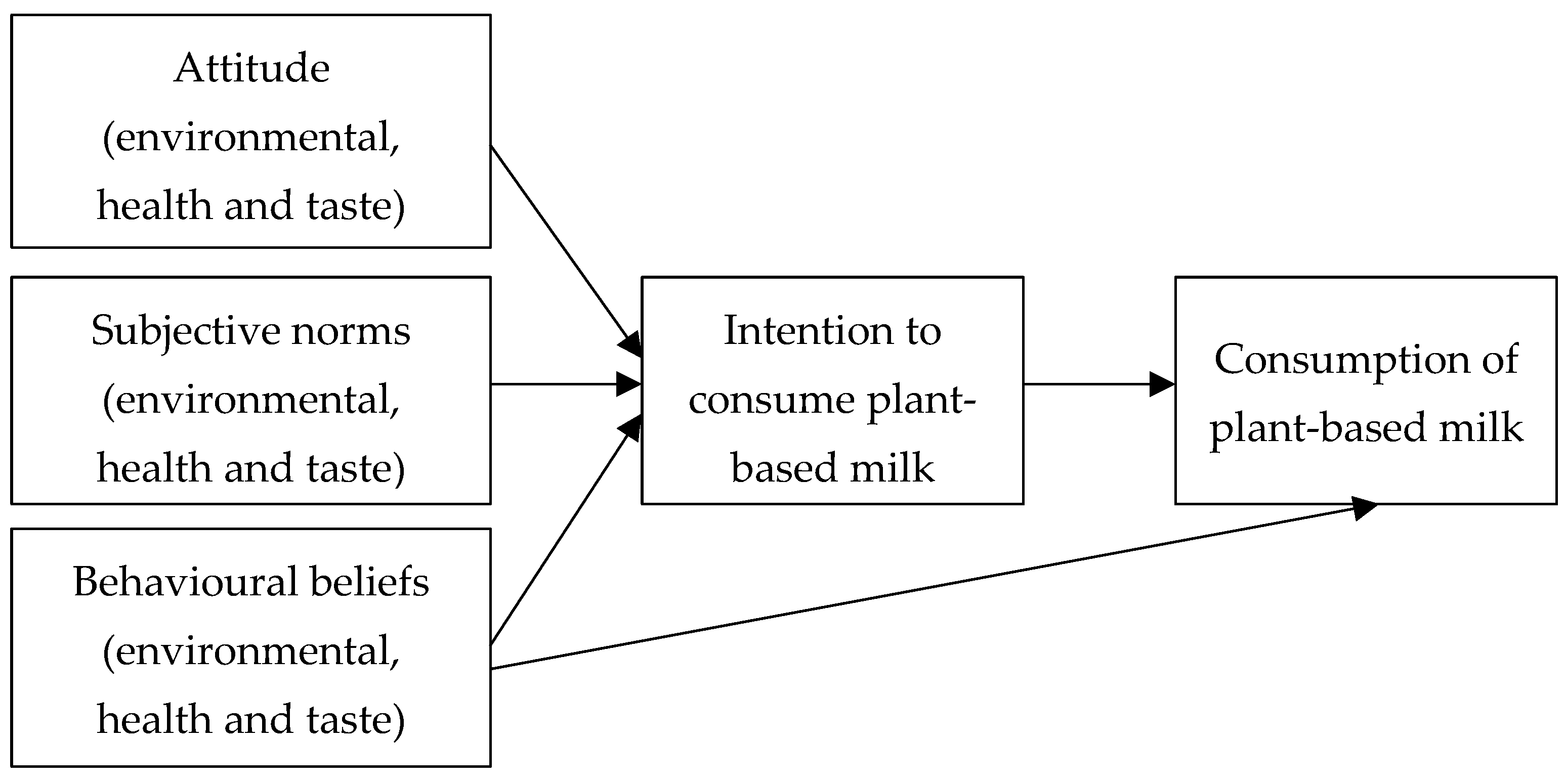

1.1. Theory of Planned Behaviour

1.2. The Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Attitude

2.3.2. Subjective Norms

2.3.3. Behavioural Beliefs

2.3.4. Intention

2.3.5. Plant-Based Milk Consumption

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Predicting Intention

3.2. Predicting Plant-Based Milk Consumption

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Notarnicola, B.; Tassielli, G.; Renzulli, P.A.; Castellani, V.; Sala, S. Environmental impacts of food consumption in Europe. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme. Novel Meat and Dairy Alternatives Could Help Curb Climate-Harming Emissions—UN. 2023. Available online: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/novel-meat-and-dairy-alternatives-could-help-curb-climate-harming#:~:text=The%20animal%20agriculture%20industry%20is,cent%20of%20global%20GHG%20emissions (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Moss, R.; Barker, S.; Falkeisen, A.; Gorman, M.; Knowles, S.; McSweeney, M.B. An investigation into consumer perception and attitudes towards plant-based alternatives to milk. Food Res. Int. 2022, 159, 111648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedenus, F.; Wirsenius, S.; Johansson, D.J.A. The importance of reduced meat and dairy consumption for meeting stringent climate change targets. Clim. Change 2014, 124, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, R.; Schnepps, A.; Pichler, A.; Meixner, O. Cow Milk versus Plant-Based Milk Substitutes: A Comparison of Product Image and Motivational Structure of Consumption. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallström, E.; Carlsson-Kanyama, A.; Börjesson, P. Environmental impact of dietary change: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 91, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhoek, H.; Lesschen, J.P.; Rood, T.; Wagner, S.; De Marco, A.; Murphy-Bokern, D.; Leip, A.; van Grinsven, H.; Sutton, M.A.; Oenema, O. Food choices, health and environment: Effects of cutting Europe’s meat and dairy intake. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 26, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H. Dairy vs. Plant-Based Milk: What Are the Environmental Impacts? 2022. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/environmental-impact-milks (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- Ramsing, R.; Santo, R.; Kim, B.F.; Altema-Johnson, D.; Wooden, A.; Chang, K.B.; Semba, R.D.; Love, D.C. Dairy and Plant-Based Milks: Implications for Nutrition and Planetary Health. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2023, 10, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeske, S.; Zannini, E.; Arendt, E.K. Past, present and future: The strength of plant-based dairy substitutes based on gluten-free raw materials. Food Res. Int. 2018, 110, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grout, L.; Baker, M.G.; French, N.; Hales, S. A Review of Potential Public Health Impacts Associated With the Global Dairy Sector. GeoHealth 2020, 4, e2019GH000213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silanikove, N.; Leitner, G.; Merin, U. The Interrelationships between Lactose Intolerance and the Modern Dairy Industry: Global Perspectives in Evolutional and Historical Backgrounds. Nutrients 2015, 7, 7312–7331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, C.A.; Malone, T.; McFadden, B.R. Beverage milk consumption patterns in the United States: Who is substituting from dairy to plant-based beverages? J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 11209–11217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, Y.; Pliner, P. Human food choices: An examination of the factors underlying acceptance/rejection of novel and familiar animal and nonanimal foods. Appetite 2005, 45, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collier, E.S.; Harris, K.L.; Bendtsen, M.; Norman, C.; Niimi, J. Just a matter of taste? Understanding rationalizations for dairy consumption and their associations with sensory expectations of plant-based milk alternatives. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 104, 104745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, K.S.; Parker, M.; Ameerally, A.; Drake, S.L.; Drake, M.A. Drivers of choice for fluid milk versus plant-based alternatives: What are consumer perceptions of fluid milk? J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 6125–6138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, O.M.; Badran, J.; Spence, L.; Drake, M.A.; Reisner, M.; Moskowitz, H.R. Measuring Acceptance of Milk and Milk Substitutes Among Younger and Older Children. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, S522–S526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardello, A.V.; Llobell, F.; Giacalone, D.; Roigard, C.M.; Jaeger, S.R. Plant-based alternatives vs dairy milk: Consumer segments and their sensory, emotional, cognitive and situational use responses to tasted products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 100, 104599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAlpine, T.; Charlesworth, J.; Martin, A.; Scott, J.; Mullan, B. An extension of the theory of planned behaviour to predict exclusive breastfeeding among Australian mother–father dyads using structural equation modelling. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2025, 30, e12760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothe, E.J.; Mullan, B.A. Interaction effects in the theory of planned behaviour: Predicting fruit and vegetable consumption in three prospective cohorts. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzgys, S.; Pickering, G.J. Gen Z and sustainable diets: Application of The Transtheoretical Model and the theory of planned behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.S.; Ahmad, M.; Ho, Y.-H.; Omar, N.A.; Lin, C.-Y. Applying an Extended Theory of Planned Behavior to Sustainable Food Consumption. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, O.; Scrimgeour, F. Willingness to adopt a more plant-based diet in China and New Zealand: Applying the theories of planned behaviour, meat attachment and food choice motives. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 93, 104294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Ritz, C.; Perez-Cueto, F.J.A. An Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Predict Intention to Consume Plant-Based Yogurt Alternatives. Foods 2021, 10, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheeler, A.; Chapman-Novakofski, K. Women Infant and Children program participants’ beliefs and consumption of soy milk: Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Nutr. Res. Pr. 2014, 8, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDermott, M.S.; Oliver, M.; Simnadis, T.; Beck, E.J.; Coltman, T.; Iverson, D.; Caputi, P.; Sharma, R. The Theory of Planned Behaviour and dietary patterns: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. 2015, 81, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yzer, M. Perceived Behavioral Control in Reasoned Action Theory: A Dual-Aspect Interpretation. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 2012, 640, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutchyn, Y.; Yzer, M. Construal Level Theory and Theory of Planned Behavior: Time Frame Effects on Salient Belief Generation. J. Health Commun. 2011, 16, 595–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwasnicka, D.; Dombrowski, S.U.; White, M.; Sniehotta, F. Theoretical explanations for maintenance of behaviour change: A systematic review of behaviour theories. Health Psychol. Rev. 2016, 10, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauch, C.E.; Edney, S.M.; Viana, J.N.M.; Gondalia, S.; Sellak, H.; Boud, S.J.; Nixon, D.D.; Ryan, J.C. Precision health in behaviour change interventions: A scoping review. Prev. Med. 2022, 163, 107192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömmer, S.; Lawrence, W.; Shaw, S.; Sara Correia, S.; Jenner, S.; Barrett, M.; Vogel, C.; Hardy-Johnson, P.; Farrell, D.; Woods-Townsend, K.; et al. Behaviour change interventions: Getting in touch with individual differences, values and emotions. J. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2020, 11, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, D.; Jaworska, D.; Affeltowicz, D.; Maison, D. Plant-Based Dairy Alternatives: Consumers’ Perceptions, Motivations, and Barriers—Results from a Qualitative Study in Poland, Germany, and France. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopwood, C.J.; Rosenfeld, D.; Chen, S.; Bleidorn, W. An Investigation of Plant-based Dietary Motives Among Vegetarians and Omnivores. Collabra Psychol. 2021, 7, 19010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, M.; Klas, A.; Ling, M.; Kothe, E. A qualitative examination of the motivations behind vegan, vegetarian, and omnivore diets in an Australian population. Appetite 2021, 167, 105614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prolific. Which Participants Will Take My Study? 2025. Available online: https://researcher-help.prolific.com/en/article/3deacf (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Constructing a Theory of Planned Behavior Questionnaire. 2006. Available online: http://people.umass.edu/~aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2024).

- McAlpine, T.; Mullan, B.A. The role of environmental cues in sugar-sweetened beverage consumption using a temporal self-regulation theory framework. Appetite 2022, 169, 105828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlesworth, J.; Mullan, B.; Moran, A. Investigating the predictors of safe food handling among parents of young children in the USA. Food Control 2021, 126, 108015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoellner, J.M.; Porter, K.J.; Chen, Y.; Hedrick, V.E.; You, W.; Hickman, M.; Estabrooks, P.A. Predicting sugar-sweetened behaviours with theory of planned behaviour constructs: Outcome and process results from the SIPsmartER behavioural intervention. Psychol. Health 2017, 32, 509–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, C.; Diamantopoulos, A. Using single-item measures for construct measurement in management research: Conceptual issues and application guidelines. Die Betriebswirtschaft 2009, 69, 195. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corporation. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 29.0.2.0; IBM Corporation: Armonk, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Maehle, N.; Iversen, N.; Hem, L.; Otnes, C. Exploring consumer preferences for hedonic and utilitarian food attributes. Br. Food J. 2015, 117, 3039–3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquier, C.; Bonthoux, F.; Baciu, M.; Ruffieux, B. Improving the effectiveness of nutritional information policies: Assessment of unconscious pleasure mechanisms involved in food-choice decisions. Nutr. Rev. 2012, 70, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C.M.; Elliott, S.J.; Meyer, S.; Leatherdale, S.T.; Majowicz, S.E. Attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control factors influencing Canadian secondary school students’ milk and milk alternatives consumption. Public Health Nutr. 2024, 27, e92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEachan, R.R.C.; Mark, C.; Taylor, N.J.; Lawton, R.J. Prospective prediction of health-related behaviours with the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2011, 5, 97–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, M. The effects of subjective norms on behaviour in the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 48, 649–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuentes, C.; Fuentes, M. Making a market for alternatives: Marketing devices and the qualification of a vegan milk substitute. J. Mark. Manag. 2017, 33, 529–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullan, B.; Novoradovskaya, E. Habit mechanisms and behavioural complexity. In The Psychology of Habit: Theory, Mechanisms, Change, and Contexts; Verplanken, B., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekanna, A.N.; Issa, A.; Bogueva, D.; Bou-Mitri, C. Consumer perception of plant-based milk alternatives: Systematic review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 8796–8805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Tan, C.; Yu, W.; Zou, L.; Wu, D.; Liu, X. Consumer Preference and Purchase Intention for Plant Milk: A Survey of Chinese Market. Foods 2025, 14, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, J.; Oliveira, A.; Calheiros, M.M. Meat, beyond the plate. Data-driven hypotheses for understanding consumer willingness to adopt a more plant-based diet. Appetite 2015, 90, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiota, M.N.; Papies, E.K.; Preston, S.D.; Sauter, D.A. Positive affect and behavior change. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2021, 39, 222–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, R.; Mary, D.; Paul, N.; French, D.P. How well does the theory of planned behaviour predict alcohol consumption? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol. Rev. 2016, 10, 148–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, V.; Bell, R.; Bruning-Mescher, S. 8—Plant-based milk alternatives: Consumer needs and marketing strategies. In Plant-Based Food Consumption; Bertella, G., Santini, C., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2024; pp. 153–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravelli, M.N.; Schoeller, D.A. Traditional Self-Reported Dietary Instruments Are Prone to Inaccuracies and New Approaches Are Needed. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobell, L.C.; Sobell, M.B. Timeline Follow-Back. In Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biochemical Methods; Litten, R.Z., Allen, J.P., Eds.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 1992; pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddelow, C.; Mullan, B.; Novoradovskaya, E. Exploring Medication Adherence Amongst Australian Adults Using an Extended Theory of Planned Behaviour. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2020, 27, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henrich, J.; Heine, S.J.; Norenzayan, A. The weirdest people in the world? Behav. Brain Sci. 2010, 33, 61–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briones, E.M.; Benham, G. An examination of the equivalency of self-report measures obtained from crowdsourced versus undergraduate student samples. Behav. Res. Methods 2017, 49, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–39 | 223 | 78.0 |

| 40–64 | 59 | 20.6 |

| 65 and over | 2 | 0.7 |

| Did not indicate | 2 | 0.7 |

| Gender | ||

| Men | 122 | 42.7 |

| Women | 160 | 55.9 |

| Non-binary | 4 | 1.4 |

| Australian residence | ||

| Yes | 285 | 99.7 |

| No | 1 | 0.3 |

| M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | - | - | −0.09 | −0.03 | 0.08 | 0.15 * | 0.07 | 0.12 ** | 0.22 ** | −0.01 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.16 ** | 0.14 * |

| 2. Age | 30.99 (10.51) | - | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.05 | −0.08 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.13 * | 0.15 * | |

| 3. Attitude—E | 4.92 (1.47) | - | 0.55 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.47 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.80 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.31 ** | ||

| 4. Attitude—H | 4.23 (1.54) | - | 0.48 ** | 0.32 * | 0.40 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.76 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.38 ** | |||

| 5. Attitude—T | 4.06 (1.97) | - | 0.28 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.90 ** | 0.69 ** | 0.57 ** | ||||

| 6. SNs—E | 4.13 (1.65) | - | 0.56 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.22 ** | |||||

| 7. SNs—H | 4.38 (1.63) | - | 0.55 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.21 ** | ||||||

| 8. SNs—T | 3.91 (1.54) | - | 0.33 ** | 0.29 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.26 ** | |||||||

| 9. BBs—E | 4.71 (1.58) | - | 0.53 ** | 0.47 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.29 ** | ||||||||

| 10. BBs—H | 4.21 (1.53) | - | 0.52 ** | 0.52 ** | 0.41 ** | |||||||||

| 11. BBs—T | 4.01 (1.99) | - | 0.68 ** | 0.53 ** | ||||||||||

| 12. Intention | 4.15 (2.25) | - | 0.78 ** | |||||||||||

| 13. Behaviour | 2.21 (1.17) | - |

| B [95% CI] | SE | β | sr2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude—E | 0.10 [−0.12, 0.32] | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.00 |

| Attitude—H | 0.02 [−0.18, 0.22] | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Attitude—T | 0.48 [0.26, 0.70] ** | 0.11 | 0.42 | 0.03 |

| SNs—E | 0.04 [−0.12, 0.20] | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| SNs—H | −0.03 [−0.19, 0.14] | 0.08 | −0.02 | −0.00 |

| SNs—T | 0.02 [−0.13, 0.18] | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| BBs—E | −0.07 [−0.28, 0.14] | 0.11 | −0.05 | −0.00 |

| BBs—H | 0.31 [0.11, 0.52] * | 0.10 | 0.21 | 0.01 |

| BBs—T | 0.19 [−0.04, 0.41] | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.00 |

| B [95% CI] | SE | β | sr2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intention | 0.40 [0.34 0.45] ** | 0.03 | 0.77 | 0.30 |

| BBs—E | −0.02 [−0.09, 0.04] | 0.03 | −0.03 | −0.00 |

| BBs—H | 0.02 [−0.05, 0.10] | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.00 |

| BBs—T | 0.00 [−0.06, 0.07] | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dorina, I.; Nikpour, A.; Mullan, B.; Uren, H. Health, Environment or Taste? Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Predict Plant-Based Milk Consumption. Foods 2025, 14, 1970. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14111970

Dorina I, Nikpour A, Mullan B, Uren H. Health, Environment or Taste? Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Predict Plant-Based Milk Consumption. Foods. 2025; 14(11):1970. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14111970

Chicago/Turabian StyleDorina, Indita, Ava Nikpour, Barbara Mullan, and Hannah Uren. 2025. "Health, Environment or Taste? Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Predict Plant-Based Milk Consumption" Foods 14, no. 11: 1970. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14111970

APA StyleDorina, I., Nikpour, A., Mullan, B., & Uren, H. (2025). Health, Environment or Taste? Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Predict Plant-Based Milk Consumption. Foods, 14(11), 1970. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14111970