Consumer Sensory Perceptions of Natural Ingredients: A Multi-Country Comparison

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant Profiles

2.2. Questionnaire

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Overall Perceptions of 20 Ingredients as Natural

3.2. Consumer Perception Differences for 20 Ingredients According to Country

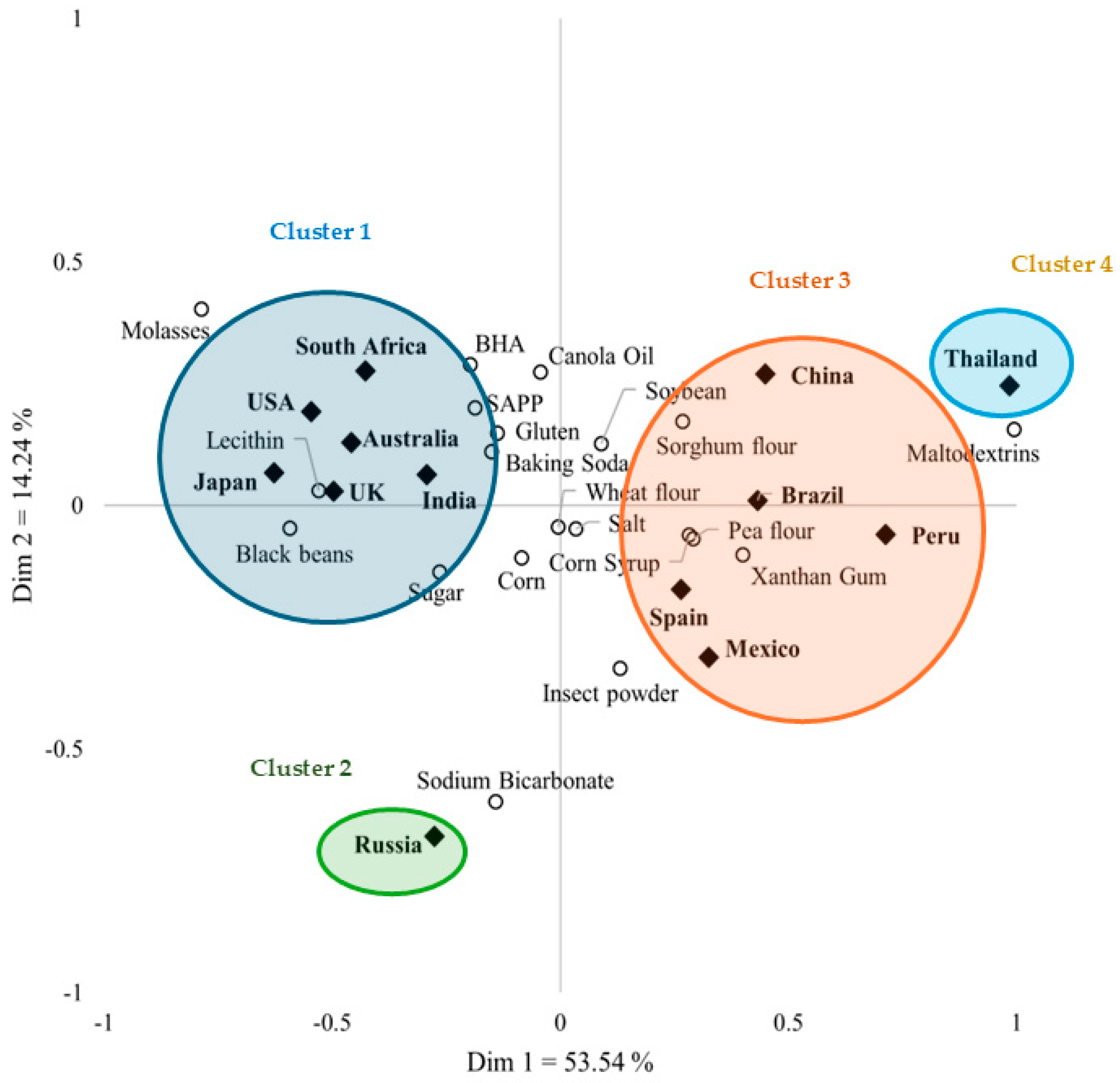

3.3. Consumer Perceptions of 20 Ingredients According to Country Clusters

3.4. Consumer Perceptions of 20 Ingredients According to Demographics

3.4.1. Analysis by Age Group

3.4.2. Analysis by Education Level

3.4.3. Analysis by Sex

3.4.4. Analysis by Number of Adults in the Household

3.4.5. Analysis by Number of Children in the Household

4. Discussion

4.1. Overall Consumer Perceptions

4.1.1. Natural Ingredients: Corn, Soybean, and Wheat Flour

4.1.2. Ingredients Generally Considered as Natural: Black Beans, Canola Oil, Pea Flour, Salt, and Sugar

4.1.3. Ingredients Rarely Perceived as Natural: BHA and SAPP

4.1.4. Mixed Natural Ingredient Perceptions

4.1.5. Demographic Characteristics

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Admonition |

| WEIRD | Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic |

| CATA | check-all-that-apply |

| TRAPD | translation, review, adjudication, pretesting, and documentation |

| BHA | butylated hydroxyanisole |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| USA | United States of America |

| SAPP | sodium acid pyrophosphate |

| GMO | genetically modified organism |

| GM | genetically modified |

| HFCS | high-fructose corn syrup |

References

- SPINS Marketing. Available online: https://www.spins.com/resources/blog/the-state-of-natural-and-organic-4-macrotrends-to-know/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- New Hope Network. Available online: https://www.newhope.com/natural-product-trends/organic-and-natural-food-trends (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Bobo, J.; Chakraborty, S. Predictably irrational consumer food preferences. Eur. J. Risk Regul. 2016, 7, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, A. Consumer Reports. Available online: https://www.consumerreports.org/food-safety/peeling-back-the-natural-food-label/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- New Hope Network. Available online: https://www.newhope.com/market-data-and-analysis/natural-products-industry-consumer-indexes-faq (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Consumers Union, Nonprofit Publisher of Consumer Reports. Available online: https://advocacy.consumerreports.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/CRCaramelColorPetitionFDA.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Regulations.gov. Available online: https://www.regulations.gov/document/FDA-2014-N-1207-0001 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/nutrition-food-labeling-and-critical-foods/use-term-natural-food-labeling (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Román, S.; Sánchez-Siles, L.M.; Siegrist, M. The importance of food naturalness for consumers: Results of a systematic review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 67, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilling, B. Supermarket News. Available online: https://www.supermarketnews.com/organic-natural/state-of-the-natural-food-industry (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Tran, H.; Veflen, N.; Jørgensen, E.J.B.; Velasco, C. Multisensory food experiences in Northern Norway: An exploratory study. Foods 2024, 13, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, J.; Heine, S.J.; Norenzayan, A. Most people are not WEIRD. Nature 2010, 466, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambers, E., V; Chambers, E., IV; Castro, M. What is “natural”? Consumer responses to selected ingredients. Foods 2018, 7, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtarelli, M.; van Houten, G. Questionnaire translation in the European company survey: Conditions conducive to the effective implementation of a TRAPD-based approach. Transl. Interpret. 2018, 10, 34–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkness, J.A. Questionnaire Translation. In Cross-Cultural Survey Methods; Harkness, J.A., van de Vijver, F.J.R., Mohler, P.P., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 35–56. ISBN 78-0-471-38526-4. [Google Scholar]

- Behr, D. Assessing the use of back translation: The shortcomings of back translation as a quality testing method. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2017, 20, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkness, J.; Pennell, B.-E.; Schoua-Glusberg, A. Survey Questionnaire Translation and Assessment. In Methods for Testing and Evaluating Survey Questionnaires; Presser, S., Rothgeb, J.M., Couper, M.P., Lessler, J.T., Martin, E., Martin, J., Singer, E., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 453–473. ISBN 978-0-471-45841-8. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, M.; Chambers, E., IV. Willingness to eat an insect based product and impact on brand equity: A global perspective. J. Sens. Stud. 2019, 34, e12486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppel, K.; Suwonsichon, S.; Chitra, U.; Lee, J.; Chambers, E. Eggs and poultry purchase, storage, and preparation practices of consumers in selected Asian countries. Foods 2014, 3, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppel, K.; Chambers, E., IV; Vázquez-Araújo, L.; Timberg, L.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A.; Suwonsichon, S. Cross-country comparison of pomegranate juice acceptance in Estonia, Spain, Thailand, and United States. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 31, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.; Chambers, E., IV. Consumer avoidance of insect containing foods: Primary emotions, perceptions and sensory characteristics driving consumers considerations. Foods 2019, 8, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Effah-Manu, L.; Wirek-Manu, F.D.; Agbenorhevi, J.K.; Maziya-Dixon, B.; Oduro, I.N. Gender-disaggregated consumer testing and descriptive sensory analysis of local and new yam varieties. Foods 2023, 12, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, K.; Shoemaker, S.P. Public perception of genetically-modified (GM) food: A nationwide Chinese consumer study. Npj Sci. Food 2018, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesseler, J.; Smart, R.D.; Thomson, J.; Zilberman, D. Foregone benefits of important food crop improvements in Sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service. Available online: https://ipad.fas.usda.gov/countrysummary/default.aspx?id=TH (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Pitakpakorn, P. Corn Milk Consumption Behavior of Consumers in Bangkok Metropolitan Area; University of Srinakharinwirot: Bangkok, Thailand, 2003; Available online: http://thesis.swu.ac.th/swuthesis/Mark/Pavinee_P.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Kotra. Available online: https://dream.kotra.or.kr/kotranews/cms/news/actionKotraBoardDetail.do?SITE_NO=3&MENU_ID=180&CONTENTS_NO=1&bbsGbn=243&bbsSn=243&pNttSn=194830 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Levy, R.B.; Moubarac, J.; Louzada, M.L.C.; Rauber, F.; Khandpur, N.; Cediel, G.; Neri, D.; Martinez-Steele, E.; et al. Ultra-processed foods: What they are and how to identify them. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 936–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelman, K.M. WebMD, Health & Diet Guide. Available online: https://www.webmd.com/diet/health-benefits-black-beans (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- GOLDEXIM. Available online: https://goldexim.net/news/black-beans (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Rotjanapaiboon, T. Study to promote nutritional status using black beans as a protein supplement. Available online: https://tarr.arda.or.th/preview/item/jZq5k34OZAm7Bkdkbe7ux (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Research and Markets. Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/report/pea-flour (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Chambers, E., V; Tran, T.; Chambers, E., IV. Natural: A $75 billion word with no definition-Why not? J. Sens. Stud. 2019, 34, e12501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez-Ramírez, D.M.; Chacon-Torrico, H.; Hernández-Vásquez, A. Household consumption of adequately iodized salt: A multi-country analysis of socioeconomic disparities. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibbins-Domingo, K.; Chertow, G.M.; Coxson, P.G.; Moran, A.; Lightwood, J.M.; Pletcher, M.J.; Goldman, L. Projected effect of dietary salt reductions on future cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service. Available online: https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/production/commodity/4239100 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Honkanen, P.; Voldnes, G. Russian consumers’ food habits: Results from a qualitative study in Moscow. Fiskeriforskning 2006, 27, 1–13. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11250/2576781 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Bruschi, V.; Shershneva, K.; Dolgopolova, I.; Canavari, M.; Teuber, R. Consumer perception of organic food in emerging markets: Evidence from Saint Petersburg, Russia. Agribusiness 2015, 31, 414–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opperman, M.; Benadé, A.J.S.; Abrecht, C.F.; Matsheka, L.L. South African seed oils are safe for human consumption. S. Afr. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 29, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Code of Federal Regulations. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Valdez, R. Verywell Health. Available online: https://www.verywellhealth.com/maltodextrin-7481887#citation-6 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service. Available online: https://ipad.fas.usda.gov/cropexplorer/cropview/commodityView.aspx?cropid=0459200&sel_year=2021&rankby=Production#:~:text=*%20Sorghum%202021.%20*%20World%20Production:%2061%2C451%20(1000%20MT)%20*%20(PS&D%20Online%20updated%2012/2024) (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Bhagavatula, S.; Rao, P.P.; Basavaraj, G.; Nagaraj, N. Sorghum and Millet Economies in Asia—Facts, Trends and Outlook. Patancheru 2013, 502, 324. Available online: https://oar.icrisat.org/7147/1/sme_asis.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Mundia, C.W.; Secchi, S.; Akamani, K.; Wang, G. A regional comparison of factors affecting global sorghum production: The case of North America, Asia and Africa’s Sahel. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.R.N.; Schober, T.J.; Bean, S.R. Novel food and non-food uses for sorghum and millets. J. Cereal Sci. 2006, 44, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyajaroenwong, P.; Laopaiboon, P.; Jaisil, P.; Laopaiboon, L. Repeated-batch ethanol production from sweet sorghum juice by Saccharomyces cerevisiae immobilized on sweet sorghum stalks. Energies 2012, 5, 1215–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon Long, T. Sorghum diseases in Thailand. In Sorghum and Millets Diseases: A Second World Review; de Milliano, W.A.J., Frederiksen, R.A., Bengston, G.D., Eds.; ICRISAT: Patancheru, India, 1992; pp. 41–43. ISBN 92-9666-201-8. [Google Scholar]

- Nuanpeng, S.; Laopaiboon, L.; Srinophakun, P.; Klanrit, P.; Jaisil, P.; Laopaiboon, P. Ethanol production from sweet sorghum juice under very high gravity conditions: Batch, repeated-batch and scale up fermentation. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 14, 1–6. Available online: https://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0717-34582011000100004 (accessed on 22 April 2025). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mohamed Nor, N.M.I.; Salleh, B.; Leslie, J.F. Fusarium species from sorghum in Thailand. Plant Pathol. J. 2019, 35, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napasintuwong, O. Food and Fertilizer Technology Center for the Asian and Pacific Region. Available online: https://ap.fftc.org.tw/article/1383 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Byrne, J. AgTechNavigator. Available online: https://www.agtechnavigator.com/Article/2024/02/08/thailand-corn-cultivation-link-to-toxic-air-pollution/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Straits Research. Available online: https://straitsresearch.com/report/high-fructose-corn-syrup-market (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Nevsky, A. Fonts in Use. Available online: https://fontsinuse.com/uses/62407/baking-soda-by-bashkir-soda-company (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Grose, R. The Spruce Eats. Available online: https://www.thespruceeats.com/mexican-food-edible-insects-4129391 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Ghosh, S.; Lee, S.-M.; Jung, C.; Meyer-Rochow, V.B. Nutritional composition of five commercial edible insects in South Korea. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2017, 20, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelemu, S.; Niassy, S.; Torto, B.; Fiaboe, K.; Affognon, H.; Tonnang, H.; Maniania, N.K.; Ekesi, S. African edible insects for food and feed: Inventory, diversity, commonalities and contribution to food security. J. Insects Food Feed 2015, 1, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honkanen, P.; Frewer, L. Russian consumers’ motives for food choice. Appetite 2009, 52, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roininen, K.; Lähteenmäki, L.; Tuorila, H. Quantification of consumer attitudes to health and hedonic characteristics of foods. Appetite 1999, 33, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindeman, M.; Väänänen, M. Measurement of ethical food choice motives. Appetite 2000, 34, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prescott, J.; Young, O.; O’Neill, L.; Yau, N.J.N.; Stevens, R. Motives for food choice: A comparison of consumers from Japan, Taiwan, Malaysia and New Zealand. Food Qual. Prefer. 2002, 13, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockie, S.; Lyons, K.; Lawrence, G.; Grice, J. Choosing organics: A path analysis of factors underlying the selection of organic food among Australian consumers. Appetite 2004, 43, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renner, B.; Sproesser, G.; Strohbach, S.; Schupp, H.T. Why we eat what we eat. The eating motivation survey (TEMS). Appetite 2012, 59, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A.; Wardle, J. Motivational factors as mediators of socioeconomic variations in dietary intake patterns. Psychol. Health 1999, 14, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornelis, M.; van Herpen, E.; van der Lans, I.; Aramyan, L. Using non-food information to identify food-choice segment membership. Food Qual. Pref. 2010, 21, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, K.M.; Walbourn, L. When college students reject food: Not just a matter of taste. Appetite 2001, 36, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Pieniak, Z.; Verbeke, W. Food-related hazards in China: Consumers’ perceptions of risk and trust in information sources. Food Control 2014, 46, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.W. Foodbank. Available online: https://www.foodbank.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=46887 (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Oh, J.E.; Yoon, H.-R. A study on dietary behavior of Chinese consumers segmented by dietary lifestyle. J. Korean Soc. Food Cult. 2017, 32, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.P.; Girgis, H.; Robinson, J. Predictors of children’s food selection: The role of children’s perceptions of the health and taste of foods. Food Qual. Pref. 2015, 40, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinozaki, N.; Murakami, K.; Kimoto, N.; Masayasu, S.; Sasaki, S. Highly processed food consumption and its association with overall diet quality in a nationwide sample of 1,318 Japanese children and adolescents: A cross-sectional analysis based on 8-day weighed dietary records. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2025, 125, 303–322.E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozin, P. The meaning of “Natural”: Process more important than content. Psychol. Sci. 2005, 16, 652–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srisukwatanachai, T.; Jiang, B.; Boonkong, A.; Kassoh, F.S.; Senawin, S. The impact of sensory perceptions and country-of-origin practices on consumer preferences for rice: A comparative study of China and Thailand. Foods 2025, 14, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Platta, A.; Mikulec, A.; Radzymińska, M.; Kowalski, S.; Skotnicka, M. Willingness to consume and purchase food with edible insects among generation Z in Poland. Foods 2024, 13, 2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symmank, C. Extrinsic and intrinsic food product attributes in consumer and sensory research: Literature review and quantification of the findings. Manag. Rev. Q. 2019, 69, 39–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atabek-Yĭgit, E.; Köklükaya, N.; Yavuz, M.; Demirhan, E. Development and validation of environmental literacy scale for adults (ELSA). J. Balt. Sci. Educ. 2014, 13, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares Filho, E.R.; Silva, R.; Campelo, P.H.; Platz, V.H.C.B.; Spers, E.E.; Freitas, M.Q.; Cruz, A.G. Think and choose! The dual impact of label information and consumer attitudes on the choice of a plant-based analog. Foods 2024, 13, 2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.; Luan, S.; Young, E.; Mirosa, M.; Bremer, P.; Torrico, D.D. The application of biometric approaches in agri-food marketing: A systematic literature review. Foods 2023, 12, 2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtakari, N.V.; Hooge, I.T.C.; Viktorsson, C.; Nyström, P.; Falck-Ytter, T.; Hessels, R.S. Eye tracking in human interaction: Possibilities and limitations. Behav. Res. Methods 2021, 53, 1592–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuschke, N. The impact of task complexity and task motivation on in-store marketing effectiveness: An eye tracking analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, M.; Reitano, A.; Loizzo, M.R. Consumer preferences for new products: Eye tracking experiment on labels and packaging for olive oil based dressing. Proceedings 2021, 70, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seninde, D.R.; Chambers, E., IV. A comparison of the percentage of “yes” (agree) responses and importance of attributes (constructs) determined using check-all-that-apply and check-all-statements (yes/no) question formats in five countries. Foods 2020, 9, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seninde, D.R.; Chambers, E., IV. Comparing the impact of check-all-that-apply (CATA) and check-all-statements (CAS) question formats on “agree” responses for different consumers’ age groups and genders across five countries. J. Sens. Stud. 2021, 36, e12697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seninde, D.R.; Chambers, E., IV. Comparing the rate-all-that-apply and rate-all-statements question formats across five countries. Foods 2021, 10, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Characteristics | Variables | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–34 | 33% |

| 35–54 | 33% | |

| 55+ | 33% | |

| Education Level | Primary School or Less | 2% |

| High School | 25% | |

| College or University | 73% | |

| Sex | Male | 50% |

| Female | 50% | |

| Number of Adults Living at Residence | 1 | 10% |

| 2 | 32% | |

| 3 | 27% | |

| 4 | 16% | |

| 5+ | 14% | |

| Number of Children Living at Residence | 0 | 54% |

| 1 | 26% | |

| 2 | 15% | |

| 3+ | 5% |

| Ingredient | Frequency of Consumers Perceiving as Natural | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Corn | 5988 | 73.10 |

| Wheat flour | 5715 | 69.77 |

| Soybean | 5656 | 69.05 |

| Pea flour | 4814 | 58.77 |

| Salt | 4687 | 57.22 |

| Black beans | 3354 | 40.95 |

| Sugar | 3338 | 40.75 |

| Canola oil | 2821 | 34.44 |

| Sorghum flour | 2534 | 30.94 |

| Corn syrup | 2368 | 28.91 |

| Maltodextrins | 1887 | 23.04 |

| Molasses | 1620 | 19.78 |

| Gluten | 1513 | 18.47 |

| Baking soda | 1232 | 15.04 |

| Sodium bicarbonate | 1186 | 14.48 |

| Xanthan gum | 964 | 11.77 |

| Insect powder | 893 | 10.90 |

| Lecithin | 712 | 8.69 |

| SAPP (Sodium acid pyrophosphate) | 167 | 2.04 |

| BHA (Butylated hydroxyanisole) | 117 | 1.43 |

| Total | 8191 | 100.00 |

| Australia | Brazil | China | India | Japan | Mexico | Peru | Russia | South Africa | Spain | Thailand | United Kingdom | USA | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baking soda | 21.0 b * | 18.1 bc | 16.3 bc | 14.9 bc | 1.7 e | 18.4 bc | 6.3 de | 7.8 de | 12.9 cd | 18.4 bc | 5.6 e | 21.0 b | 33.2 a | <0.0001 |

| BHA | 2.2 abc | 1.7 abc | 1.1 bc | 3.0 ab | 0.2 c | 1.4 bc | 0.6 c | 0.2 c | 1.0 bc | 0.6 c | 1.1 bc | 1.6 abc | 3.8 a | <0.0001 |

| Black beans | 61.4 ab | 8.1 ef | 12.2 e | 54.6 b | 62.5 ab | 24.1 d | 10.3 ef | 65.2 a | 68.1 a | 36.0 c | 1.1 f | 65.7 a | 62.7 ab | <0.0001 |

| Canola oil | 43.3 cd | 45.1 bc | 52.9 ab | 34.3 de | 27.9 ef | 40.6 cd | 30.2 ef | 9.7 g | 61.0 a | 11.1 g | 22.2 f | 27.6 ef | 41.9 cd | <0.0001 |

| Corn | 79.5 cde | 83.3 bcd | 74.8 def | 82.9 bcd | 61.6 g | 92.2 a | 89.5 ab | 84.9 abc | 77.0 cdef | 80.2 cde | 3.2 h | 72.2 ef | 69.0 fg | <0.0001 |

| Corn syrup | 22.1 c | 22.5 c | 27.8 bc | 21.9 c | 9.2 d | 46.3 a | 32.9 b | 27.0 bc | 26.3 bc | 44.6 a | 48.4 a | 27.3 bc | 19.5 c | <0.0001 |

| Gluten | 26.2 ab | 11.6 ef | 28.3 ab | 12.7 ef | 13.5 ef | 14.4 def | 16.0 cde | 10.0 ef | 21.3 bcd | 24.1 b | 7.3 f | 31.7 a | 23.0 bc | <0.0001 |

| Insect powder | 4.8 f | 12.2 bcde | 14.1 bcd | 4.4 f | 15.9 bc | 27.8 a | 7.1 ef | 18.1 b | 3.7 f | 10.8 cde | 8.6 def | 7.1 ef | 7.1 ef | <0.0001 |

| Lecithin | 21.4 a | 4.8 cd | 7.5 c | 5.9 cd | 5.9 cd | 3.8 cd | 0.8 d | 15.2 b | 15.9 b | 4.3 cd | 1.0 d | 13.0 b | 13.7 b | <0.0001 |

| Maltodextrins | 6.5 e | 38.9 bc | 42.2 b | 3.8 e | 1.4 e | 21.1 d | 70.6 a | 2.7 e | 3.0 e | 34.0 c | 65.1 a | 5.6 e | 4.6 e | <0.0001 |

| Molasses | 39.4 ab | 3.2 de | 9.5 d | 23.8 c | 36.8 b | 1.9 de | 2.1 de | 8.1 de | 44.6 a | 2.1 de | 1.1 e | 39.5 ab | 45.1 a | <0.0001 |

| Pea flour | 38.4 fg | 77.5 bc | 66.7 d | 49.5 e | 30.0 g | 86.7 ab | 80.3 ab | 69.2 cd | 50.2 e | 47.3 ef | 88.3 a | 41.9 ef | 38.1 fg | <0.0001 |

| Salt | 57.9 cd | 35.2 f | 33.0 f | 62.2 c | 49.8 de | 57.0 cde | 48.3 e | 78.1 b | 57.0 cde | 62.7 c | 93.7 a | 54.4 cde | 54.4 cde | <0.0001 |

| SAPP | 2.7 ab | 2.4 ab | 2.2 ab | 4.0 a | 1.3 ab | 1.6 ab | 0.6 b | 1.3 ab | 2.2 ab | 1.1 b | 1.6 ab | 2.4 ab | 3.2 ab | 0.001 |

| Sodium bicarbonate | 19.5 bc | 10.5 def | 6.2 ef | 6.0 ef | 3.8 f | 25.1 b | 13.2 cd | 46.3 a | 11.0 de | 13.3 cd | 3.8 f | 16.5 cd | 13.0 cd | <0.0001 |

| Sorghum flour | 36.3 c | 18.3 fg | 60.3 a | 26.7 def | 2.1 h | 35.4 cd | 22.4 fg | 32.1 cde | 45.4 b | 20.8 fg | 63.3 a | 15.1 g | 24.0 efg | <0.0001 |

| Soybean | 68.9 cd | 81.1 b | 67.0 cde | 81.7 b | 71.6 c | 61.9 de | 69.7 cd | 41.3 f | 69.8 cd | 70.0 cd | 94.1 a | 58.9 e | 61.6 de | <0.0001 |

| Sugar | 50.3 bcd | 41.3 de | 20.8 g | 50.8 bc | 45.1 bcd | 32.5 ef | 32.5 ef | 72.5 a | 41.9 cde | 24.6 fg | 17.1 g | 46.3 bcd | 53.8 b | <0.0001 |

| Wheat flour | 65.7 cde | 42.5 f | 68.7 bcde | 86.0 a | 61.3 e | 64.9 de | 75.9 b | 91.9 a | 71.9 bcd | 73.8 bc | 73.2 bcd | 68.3 bcde | 62.9 e | <0.0001 |

| Xanthan gum | 8.9 ef | 16.3 bc | 15.4 bcd | 4.8 fg | 1.4 g | 31.1 a | 21.3 b | 4.8 fg | 7.8 ef | 13.0 cde | 9.7 def | 10.3 cdef | 8.3 ef | <0.0001 |

| Ingredient | Age | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | India | Japan | South Africa | United Kingdom | USA | Russia | Brazil | China | Mexico | Peru | Spain | Thailand | ||

| Baking soda | 18–34 yrs | 21.0 ab | 20.4 a | 1.9 | 10.5 | 16.7 | 26.3 b | 4.8 | 7.1 b | 9.5 b | 8.1 c | 2.4 b | 8.6 b | 4.8 |

| 35–54 yrs | 15.7 b | 13.3 b | 2.4 | 13.8 | 22.9 | 33.2 ab | 11.0 | 20.5 a | 22.4 a | 18.6 b | 6.2 ab | 21.4 a | 3.3 | |

| 55 yrs + | 26.2 a | 11.0 b | 1.0 | 14.3 | 23.3 | 40.0 a | 7.6 | 26.7 a | 17.1 a | 28.6 a | 10.5 a | 25.2 a | 8.6 | |

| p-value | 0.031 | 0.019 | 0.524 | 0.447 | 0.174 | 0.012 | 0.060 | <0.0001 | 0.002 | <0.0001 | 0.003 | <0.0001 | 0.053 | |

| BHA | 18–34 yrs | 2.4 | 5.2 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 5.3 | 0.5 | 2.4 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2.4 |

| 35–54 yrs | 2.4 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.5 | |

| 55 yrs + | 1.9 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 3.8 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 0.5 | |

| p-value | 0.930 | 0.072 | 0.368 | 0.133 | 0.492 | 0.302 | 0.368 | 0.228 | 0.364 | 1.000 | 0.778 | 0.172 | 0.099 | |

| Black beans | 18–34 yrs | 51.9 b | 53.6 | 50.0 c | 61.9 b | 57.1 b | 50.2 b | 63.3 | 7.1 | 11.9 | 21.0 b | 9.5 | 30.5 | 1.4 |

| 35–54 yrs | 58.1 b | 55.7 | 61.4 b | 65.7 b | 70.0 a | 66.4 a | 68.6 | 6.2 | 10.5 | 19.5 b | 10.0 | 36.7 | 0.0 | |

| 55 yrs + | 74.3 a | 54.8 | 76.2 a | 76.7 a | 70.0 a | 71.4 a | 63.8 | 11.0 | 14.3 | 31.9 a | 11.4 | 41.0 | 1.9 | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.905 | <0.0001 | 0.003 | 0.006 | <0.0001 | 0.460 | 0.167 | 0.485 | 0.005 | 0.800 | 0.080 | 0.153 | |

| Canola oil | 18–34 yrs | 32.9 b | 30.3 b | 27.6 | 52.9 b | 24.3 | 33.5 b | 12.9 | 44.8 | 52.4 | 38.1 | 29.5 | 11.9 | 12.4 b |

| 35–54 yrs | 39.0 b | 29.5 b | 27.6 | 61.9 ab | 32.9 | 43.6 a | 9.5 | 42.9 | 59.0 | 39.5 | 29.0 | 11.0 | 23.8 a | |

| 55 yrs + | 58.1 a | 42.9 a | 28.6 | 68.1 a | 25.7 | 48.6 a | 6.7 | 47.6 | 47.1 | 44.3 | 31.9 | 10.5 | 30.5 a | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.005 | 0.969 | 0.006 | 0.110 | 0.006 | 0.100 | 0.615 | 0.050 | 0.401 | 0.792 | 0.894 | <0.0001 | |

| Corn | 18–34 yrs | 71.0 c | 85.8 | 51.9 b | 80.0 | 61.4 b | 65.6 | 82.9 | 81.0 | 78.6 a | 91.4 | 84.8 b | 76.2 | 4.8 |

| 35–54 yrs | 79.5 b | 81.0 | 61.9 a | 72.9 | 80.5 a | 70.6 | 86.7 | 85.2 | 81.0 a | 90.0 | 91.4 a | 80.0 | 1.9 | |

| 55 yrs + | 88.1 a | 81.9 | 71.0 a | 78.1 | 74.8 a | 71.0 | 85.2 | 83.8 | 64.8 b | 95.2 | 92.4 a | 84.3 | 2.9 | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.379 | 0.000 | 0.198 | <0.0001 | 0.408 | 0.545 | 0.487 | 0.000 | 0.117 | 0.021 | 0.115 | 0.236 | |

| Corn syrup | 18–34 yrs | 15.7 b | 21.8 | 9.0 | 21.4 b | 18.6 b | 13.4 b | 26.2 | 25.2 | 28.6 ab | 41.4 b | 38.6 | 33.8 b | 50.5 |

| 35–54 yrs | 16.7 b | 24.8 | 8.6 | 22.9 b | 26.7 b | 21.3 a | 30.0 | 18.6 | 33.8 a | 44.3 ab | 27.6 | 40.0 b | 52.4 | |

| 55 yrs + | 33.8 a | 19.0 | 10.0 | 34.8 a | 36.7 a | 23.8 a | 24.8 | 23.8 | 21.0 b | 53.3 a | 32.4 | 60.0 a | 42.4 | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.367 | 0.876 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.020 | 0.458 | 0.228 | 0.013 | 0.039 | 0.057 | <0.0001 | 0.094 | |

| Gluten | 18–34 yrs | 23.8 b | 13.7 | 10.0 b | 19.0 | 30.5 | 26.8 | 10.0 | 8.1 b | 25.2 b | 16.2 a | 10.5 b | 21.9 | 9.5 |

| 35–54 yrs | 18.1 b | 14.8 | 18.6 a | 19.0 | 31.9 | 21.8 | 11.9 | 11.0 ab | 38.1 a | 9.0 b | 14.3 b | 21.4 | 3.8 | |

| 55 yrs + | 36.7 a | 9.5 | 11.9 b | 25.7 | 32.9 | 20.5 | 8.1 | 15.7 a | 21.4 b | 18.1 a | 23.3 a | 29.0 | 8.6 | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.232 | 0.026 | 0.156 | 0.870 | 0.270 | 0.429 | 0.048 | 0.000 | 0.021 | 0.001 | 0.124 | 0.055 | |

| Insect powder | 18–34 yrs | 5.2 | 6.2 | 17.1 | 5.7 | 9.0 | 7.7 | 20.5 | 12.4 | 14.8 | 25.7 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 8.6 |

| 35–54 yrs | 6.7 | 2.9 | 13.3 | 2.9 | 7.6 | 7.1 | 18.1 | 12.4 | 11.9 | 28.1 | 6.2 | 13.3 | 7.6 | |

| 55 yrs + | 2.4 | 4.3 | 17.1 | 2.4 | 4.8 | 6.7 | 15.7 | 11.9 | 15.7 | 29.5 | 8.1 | 11.9 | 9.5 | |

| p-value | 0.111 | 0.256 | 0.468 | 0.144 | 0.222 | 0.926 | 0.448 | 0.985 | 0.507 | 0.679 | 0.751 | 0.101 | 0.785 | |

| Lecithin | 18–34 yrs | 9.5 b | 6.2 | 3.8 | 4.8 c | 7.1 b | 9.1 b | 12.4 | 3.3 | 7.6 | 3.3 | 1.0 | 4.8 | 1.4 |

| 35–54 yrs | 13.8 b | 5.2 | 8.1 | 12.4 b | 12.4 b | 11.4 b | 18.1 | 5.2 | 4.8 | 2.9 | 0.5 | 3.8 | 0.0 | |

| 55 yrs + | 41.0 a | 6.2 | 5.7 | 30.5 a | 19.5 a | 20.5 a | 15.2 | 5.7 | 10.0 | 5.2 | 1.0 | 4.3 | 1.4 | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.894 | 0.174 | <0.0001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.266 | 0.480 | 0.124 | 0.403 | 0.818 | 0.891 | 0.220 | |

| Maltodextrins | 18–34 yrs | 9.0 a | 3.3 | 1.4 | 2.9 | 2.4 b | 4.3 | 3.3 | 39.0 | 46.2 a | 15.2 b | 66.7 | 27.6 b | 62.9 |

| 35–54 yrs | 2.9 b | 3.3 | 1.4 | 4.8 | 7.1 a | 3.8 | 3.3 | 39.0 | 51.4 a | 22.9 ab | 71.0 | 34.8 ab | 64.8 | |

| 55 yrs + | 7.6 a | 4.8 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 7.1 a | 5.7 | 1.4 | 38.6 | 29.0 b | 25.2 a | 74.3 | 39.5 a | 67.6 | |

| p-value | 0.027 | 0.674 | 1.000 | 0.135 | 0.049 | 0.623 | 0.381 | 0.993 | <0.0001 | 0.032 | 0.229 | 0.035 | 0.589 | |

| Molasses | 18–34 yrs | 24.8 b | 18.5 | 32.4 | 26.7 c | 20.0 c | 34.4 c | 7.6 | 4.3 | 11.4 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 3.8 | 1.0 |

| 35–54 yrs | 29.0 b | 25.2 | 35.7 | 44.8 b | 42.4 b | 45.5 b | 7.1 | 2.4 | 6.2 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| 55 yrs + | 64.3 a | 27.6 | 42.4 | 62.4 a | 56.2 a | 55.2 a | 9.5 | 2.9 | 11.0 | 1.4 | 2.9 | 1.4 | 1.4 | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.074 | 0.097 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.000 | 0.639 | 0.512 | 0.130 | 0.466 | 0.578 | 0.088 | 0.866 | |

| Pea flour | 18–34 yrs | 31.4 b | 47.4 | 21.0 b | 42.9 b | 35.2 | 32.1 b | 62.9 | 74.3 | 71.0 a | 82.9 b | 70.0 b | 41.4 b | 84.8 |

| 35–54 yrs | 33.8 b | 47.6 | 35.2 a | 48.1 b | 46.2 | 38.4 ab | 72.4 | 78.1 | 75.7 a | 85.2 b | 81.9 a | 45.7 ab | 88.6 | |

| 55 yrs + | 50.0 a | 53.8 | 33.8 a | 59.5 a | 44.3 | 43.8 a | 72.4 | 80.0 | 53.3 b | 91.9 a | 89.0 a | 54.8 a | 91.4 | |

| p-value | 0.000 | 0.329 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.052 | 0.047 | 0.051 | 0.362 | <0.0001 | 0.018 | <0.0001 | 0.020 | 0.104 | |

| Salt | 18–34 yrs | 52.9 b | 66.4 | 52.9 a | 54.3 | 47.1 b | 51.2 | 72.9 | 34.3 | 33.3 | 48.6 b | 40.0 b | 56.2 b | 91.9 |

| 35–54 yrs | 50.5 b | 61.4 | 41.9 b | 55.2 | 56.2 ab | 56.4 | 77.6 | 33.3 | 37.6 | 56.2 b | 50.0 a | 61.0 b | 95.2 | |

| 55 yrs + | 70.5 a | 59.0 | 54.8 a | 61.4 | 60.0 a | 55.7 | 83.8 | 38.1 | 28.1 | 66.2 a | 54.8 a | 71.0 a | 93.8 | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.289 | 0.018 | 0.276 | 0.025 | 0.510 | 0.025 | 0.558 | 0.116 | 0.001 | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.373 | |

| SAPP | 18–34 yrs | 2.9 | 6.6 a | 1.0 | 4.8 a | 1.0 | 2.9 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 3.8 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 1.9 |

| 35–54 yrs | 2.4 | 2.9 b | 1.9 | 1.4 b | 3.8 | 3.3 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.0 | |

| 55 yrs + | 2.9 | 2.4 b | 1.0 | 0.5 b | 2.4 | 3.3 | 0.5 | 3.8 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.9 | |

| p-value | 0.941 | 0.050 | 0.603 | 0.008 | 0.159 | 0.954 | 0.413 | 0.159 | 0.161 | 0.666 | 0.778 | 0.562 | 0.666 | |

| Sodium bicarbonate | 18–34 yrs | 15.2 b | 8.1 | 3.8 | 6.7 b | 11.0 b | 9.6 | 40.5 | 7.1 b | 5.2 ab | 21.4 b | 8.6 b | 8.1 b | 8.1 a |

| 35–54 yrs | 15.2 b | 5.7 | 3.8 | 10.5 ab | 18.6 a | 12.3 | 46.7 | 9.0 b | 3.8 b | 21.0 b | 14.3 ab | 10.5 b | 0.5 b | |

| 55 yrs + | 28.1 a | 4.3 | 3.8 | 15.7 a | 20.0 a | 17.1 | 51.9 | 15.2 a | 9.5 a | 32.9 a | 16.7 a | 21.4 a | 2.9 b | |

| p-value | 0.001 | 0.260 | 1.000 | 0.012 | 0.027 | 0.066 | 0.063 | 0.018 | 0.041 | 0.006 | 0.042 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Sorghum flour | 18–34 yrs | 22.4 b | 27.0 | 1.4 | 30.5 b | 9.0 b | 16.3 b | 23.3 b | 14.3 | 61.4 a | 24.8 b | 18.6 | 14.8 b | 59.5 |

| 35–54 yrs | 28.1 b | 28.6 | 3.3 | 49.0 a | 17.6 a | 22.7 b | 35.7 a | 19.0 | 70.5 a | 37.1 a | 22.4 | 17.6 b | 62.9 | |

| 55 yrs + | 58.6 a | 24.8 | 1.4 | 56.7 a | 18.6 a | 32.9 a | 37.1 a | 21.4 | 49.0 b | 44.3 a | 26.2 | 30.0 a | 67.6 | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.676 | 0.285 | <0.0001 | 0.011 | 0.000 | 0.004 | 0.156 | <0.0001 | 0.000 | 0.174 | 0.000 | 0.224 | |

| Soybean | 18–34 yrs | 65.7 b | 81.5 | 63.8 b | 66.2 | 9.0 b | 52.6 b | 33.3 b | 81.0 | 73.3 a | 59.5 b | 59.0 c | 71.0 | 92.4 |

| 35–54 yrs | 61.0 b | 79.5 | 73.8 a | 68.1 | 17.6 a | 65.4 a | 45.2 a | 81.4 | 74.8 a | 55.7 b | 70.0 b | 69.5 | 94.3 | |

| 55 yrs + | 80.0 a | 84.3 | 77.1 a | 75.2 | 18.6 a | 66.7 a | 45.2 a | 81.0 | 52.9 b | 70.5 a | 80.0 a | 69.5 | 95.7 | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.447 | 0.007 | 0.104 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.017 | 0.990 | <0.0001 | 0.005 | <0.0001 | 0.934 | 0.346 | |

| Sugar | 18–34 yrs | 41.4 b | 53.6 | 45.2 | 38.1 | 39.5 | 44.5 b | 69.0 | 22.9 c | 21.0 | 20.0 c | 20.0 b | 16.7 b | 20.0 |

| 35–54 yrs | 43.8 b | 47.6 | 42.9 | 40.0 | 49.5 | 59.7 a | 70.0 | 44.3 b | 21.0 | 29.5 b | 35.2 a | 27.6 a | 16.7 | |

| 55 yrs + | 65.7 a | 51.4 | 47.1 | 47.6 | 50.0 | 57.1 a | 78.6 | 56.7 a | 20.5 | 48.1 a | 42.4 a | 29.5 a | 14.8 | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.468 | 0.677 | 0.112 | 0.052 | 0.004 | 0.055 | <0.0001 | 0.990 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.004 | 0.354 | |

| Wheat flour | 18–34 yrs | 59.5 b | 84.8 | 60.5 | 71.0 | 63.3 | 63.6 | 88.6 b | 38.6 | 72.9 a | 56.7 b | 79.0 | 66.7 b | 76.2 |

| 35–54 yrs | 53.8 b | 87.6 | 59.0 | 70.5 | 69.5 | 62.1 | 91.0 b | 40.5 | 81.4 a | 66.2 a | 77.1 | 70.5 b | 72.4 | |

| 55 yrs + | 83.8 a | 85.7 | 64.3 | 74.3 | 71.9 | 62.9 | 96.2 a | 48.6 | 51.9 b | 71.9 a | 71.4 | 84.3 a | 71.0 | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.701 | 0.523 | 0.639 | 0.150 | 0.947 | 0.014 | 0.089 | <0.0001 | 0.004 | 0.165 | <0.0001 | 0.457 | |

| Xanthan gum | 18–34 yrs | 8.6 ab | 4.3 | 1.0 | 6.7 | 5.7 b | 7.2 | 5.2 | 15.2 | 19.0 | 31.0 | 24.3 | 14.3 | 8.1 |

| 35–54 yrs | 6.2 b | 4.8 | 1.4 | 6.2 | 12.4 a | 8.5 | 5.7 | 16.7 | 15.7 | 31.4 | 17.1 | 12.9 | 12.9 | |

| 55 yrs + | 11.9 a | 5.2 | 1.9 | 10.5 | 12.9 a | 9.0 | 3.3 | 17.1 | 11.4 | 31.0 | 22.4 | 11.9 | 8.1 | |

| p-value | 0.118 | 0.896 | 0.713 | 0.199 | 0.027 | 0.773 | 0.480 | 0.860 | 0.096 | 0.993 | 0.180 | 0.766 | 0.163 |

| Ingredient | Education | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | India | Japan | South Africa | United Kingdom | USA | Russia | Brazil | China | Mexico | Peru | Spain | Thailand | ||

| Baking soda | ≤HS | 19.5 | 26.7 | 0.9 | 17.7 | 22.9 | 35.0 | 1.8 | 18.9 | 14.2 | 10.7 | 8.2 | 15.9 | 1.1 |

| COL+ | 21.9 | 14.3 | 2.2 | 10.0 | 19.7 | 31.5 | 8.4 | 17.5 | 16.9 | 18.8 | 6.2 | 20.7 | 6.3 | |

| p-value | 0.473 | 0.064 | 0.233 | 0.005 | 0.349 | 0.354 | 0.080 | 0.654 | 0.445 | 0.283 | 0.534 | 0.123 | 0.047 | |

| BHA | ≤HS | 2.0 | 16.7 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 4.1 | 0.0 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 |

| COL+ | 2.4 | 2.3 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 3.6 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.3 | |

| p-value | 0.751 | <0.0001 | 0.463 | 0.308 | 0.218 | 0.739 | 0.759 | 0.362 | 0.651 | 0.517 | 0.513 | 0.905 | 0.279 | |

| Black beans | ≤HS | 59.4 | 36.7 | 63.1 | 64.5 | 67.3 | 61.6 | 62.5 | 8.1 | 10.4 | 32.1 | 8.2 | 32.1 | 1.1 |

| COL+ | 62.8 | 55.6 | 62.3 | 70.2 | 64.7 | 63.7 | 65.5 | 8.1 | 12.7 | 23.8 | 10.5 | 39.5 | 1.1 | |

| p-value | 0.386 | 0.043 | 0.842 | 0.141 | 0.492 | 0.582 | 0.653 | 0.992 | 0.480 | 0.311 | 0.567 | 0.053 | 1.000 | |

| Canola oil | ≤HS | 44.2 | 33.3 | 28.4 | 63.6 | 22.0 | 40.1 | 10.7 | 45.9 | 47.8 | 60.7 | 16.4 | 9.5 | 14.4 |

| COL+ | 42.7 | 34.3 | 27.7 | 59.4 | 31.2 | 43.5 | 9.6 | 44.5 | 54.2 | 39.7 | 31.6 | 12.6 | 23.5 | |

| p-value | 0.714 | 0.916 | 0.856 | 0.294 | 0.013 | 0.401 | 0.785 | 0.715 | 0.183 | 0.027 | 0.014 | 0.215 | 0.055 | |

| Corn | ≤HS | 80.5 | 73.3 | 61.7 | 76.6 | 75.1 | 69.4 | 87.5 | 86.5 | 69.4 | 100.0 | 80.3 | 80.7 | 5.6 |

| COL+ | 78.9 | 83.4 | 61.5 | 77.2 | 70.4 | 68.8 | 84.7 | 81.1 | 76.2 | 91.9 | 90.5 | 79.6 | 2.8 | |

| p-value | 0.630 | 0.155 | 0.962 | 0.870 | 0.198 | 0.863 | 0.573 | 0.076 | 0.108 | 0.116 | 0.014 | 0.730 | 0.165 | |

| Corn syrup | ≤HS | 21.9 | 23.3 | 9.5 | 29.4 | 24.9 | 18.7 | 26.8 | 22.4 | 20.9 | 64.3 | 44.3 | 42.9 | 41.1 |

| COL+ | 22.2 | 21.8 | 9.1 | 24.6 | 28.8 | 20.2 | 27.0 | 22.6 | 29.6 | 45.5 | 31.6 | 46.1 | 49.6 | |

| p-value | 0.941 | 0.843 | 0.872 | 0.181 | 0.281 | 0.629 | 0.972 | 0.942 | 0.045 | 0.052 | 0.046 | 0.420 | 0.135 | |

| Gluten | ≤HS | 22.7 | 10.0 | 11.3 | 22.9 | 31.8 | 22.4 | 5.4 | 10.4 | 25.4 | 14.3 | 8.2 | 18.9 | 3.3 |

| COL+ | 28.5 | 12.8 | 14.7 | 20.3 | 31.7 | 23.5 | 10.5 | 12.4 | 29.0 | 14.5 | 16.9 | 28.7 | 8.0 | |

| p-value | 0.106 | 0.652 | 0.227 | 0.435 | 0.969 | 0.752 | 0.226 | 0.447 | 0.404 | 0.981 | 0.080 | 0.004 | 0.119 | |

| Insect powder | ≤HS | 5.2 | 10.0 | 13.5 | 3.9 | 4.5 | 4.8 | 19.6 | 10.8 | 10.4 | 28.6 | 6.6 | 9.1 | 3.3 |

| COL+ | 4.5 | 4.2 | 17.2 | 3.5 | 8.8 | 9.2 | 17.9 | 13.2 | 15.1 | 27.7 | 7.2 | 12.3 | 9.4 | |

| p-value | 0.690 | 0.130 | 0.232 | 0.803 | 0.039 | 0.030 | 0.753 | 0.367 | 0.169 | 0.924 | 0.853 | 0.203 | 0.055 | |

| Lecithin | ≤HS | 19.1 | 16.7 | 5.4 | 15.2 | 12.2 | 12.9 | 5.4 | 3.5 | 8.2 | 3.6 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 0.0 |

| COL+ | 23.0 | 5.3 | 6.1 | 16.3 | 13.5 | 14.3 | 16.2 | 5.7 | 7.3 | 3.8 | 0.9 | 6.0 | 1.1 | |

| p-value | 0.252 | 0.010 | 0.713 | 0.707 | 0.647 | 0.620 | 0.031 | 0.206 | 0.711 | 0.948 | 0.464 | 0.025 | 0.316 | |

| Maltodextrins | ≤HS | 5.2 | 3.3 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 4.9 | 4.1 | 5.4 | 37.8 | 26.1 | 25.0 | 70.5 | 31.1 | 60.0 |

| COL+ | 7.4 | 3.8 | 1.5 | 4.3 | 6.0 | 5.1 | 2.4 | 39.6 | 46.6 | 20.9 | 70.7 | 36.5 | 65.9 | |

| p-value | 0.272 | 0.892 | 0.905 | 0.016 | 0.566 | 0.560 | 0.199 | 0.652 | <0.0001 | 0.607 | 0.980 | 0.150 | 0.275 | |

| Molasses | ≤HS | 38.2 | 16.7 | 31.1 | 41.6 | 39.6 | 46.6 | 5.4 | 1.5 | 7.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 0.0 |

| COL+ | 40.1 | 24.1 | 40.0 | 46.4 | 39.5 | 43.8 | 8.4 | 4.3 | 10.1 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 1.3 | |

| p-value | 0.641 | 0.350 | 0.028 | 0.243 | 0.978 | 0.474 | 0.432 | 0.051 | 0.360 | 0.452 | 0.234 | 0.237 | 0.279 | |

| Pea flour | ≤HS | 35.5 | 40.0 | 28.8 | 47.6 | 42.4 | 37.1 | 67.9 | 77.2 | 55.2 | 82.1 | 73.8 | 44.9 | 81.1 |

| COL+ | 40.4 | 50.1 | 30.6 | 51.6 | 41.6 | 39.0 | 69.3 | 77.6 | 69.8 | 86.9 | 81.0 | 49.4 | 89.4 | |

| p-value | 0.215 | 0.282 | 0.637 | 0.333 | 0.826 | 0.622 | 0.819 | 0.904 | 0.002 | 0.472 | 0.176 | 0.263 | 0.023 | |

| Salt | ≤HS | 54.6 | 76.7 | 48.6 | 60.2 | 56.3 | 55.4 | 80.4 | 33.2 | 26.9 | 71.4 | 47.5 | 59.8 | 86.7 |

| COL+ | 60.2 | 61.6 | 50.5 | 55.1 | 53.2 | 53.6 | 77.9 | 36.7 | 34.7 | 56.3 | 48.3 | 65.3 | 94.8 | |

| p-value | 0.166 | 0.096 | 0.659 | 0.219 | 0.450 | 0.639 | 0.669 | 0.373 | 0.088 | 0.115 | 0.907 | 0.157 | 0.003 | |

| SAPP | ≤HS | 2.4 | 13.3 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 3.7 | 1.8 | 2.7 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 2.2 |

| COL+ | 2.9 | 3.5 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 1.2 | 2.2 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 1.5 | |

| p-value | 0.699 | 0.007 | 0.894 | 0.526 | 0.930 | 0.449 | 0.720 | 0.659 | 0.192 | 0.494 | 0.513 | 0.082 | 0.604 | |

| Sodium bicarbonate | ≤HS | 16.7 | 20.0 | 3.6 | 9.5 | 15.5 | 12.6 | 39.3 | 6.9 | 10.4 | 35.7 | 11.5 | 12.2 | 4.4 |

| COL+ | 21.4 | 5.3 | 3.9 | 11.8 | 17.1 | 13.4 | 47.0 | 12.9 | 5.0 | 24.6 | 13.4 | 14.4 | 3.7 | |

| p-value | 0.151 | 0.001 | 0.843 | 0.383 | 0.591 | 0.764 | 0.267 | 0.016 | 0.021 | 0.185 | 0.680 | 0.416 | 0.735 | |

| Sorghum flour | ≤HS | 35.1 | 20.0 | 0.5 | 40.7 | 13.9 | 19.4 | 33.9 | 17.0 | 53.0 | 39.3 | 16.4 | 15.5 | 58.9 |

| COL+ | 37.2 | 27.1 | 2.9 | 48.1 | 15.8 | 28.0 | 31.9 | 19.1 | 62.3 | 35.2 | 23.0 | 25.4 | 64.1 | |

| p-value | 0.584 | 0.391 | 0.036 | 0.071 | 0.502 | 0.012 | 0.755 | 0.493 | 0.051 | 0.660 | 0.238 | 0.002 | 0.345 | |

| Soybean | ≤HS | 65.3 | 83.3 | 66.7 | 64.9 | 59.6 | 61.9 | 53.6 | 82.6 | 56.0 | 46.4 | 50.8 | 66.6 | 88.9 |

| COL+ | 71.2 | 81.7 | 74.3 | 72.7 | 58.4 | 61.3 | 40.1 | 80.1 | 70.0 | 62.6 | 71.7 | 73.1 | 95.0 | |

| p-value | 0.118 | 0.822 | 0.044 | 0.041 | 0.775 | 0.879 | 0.050 | 0.418 | 0.002 | 0.085 | 0.001 | 0.076 | 0.023 | |

| Sugar | ≤HS | 51.8 | 53.3 | 41.4 | 47.2 | 49.0 | 53.7 | 71.4 | 35.1 | 19.4 | 25.0 | 16.4 | 21.6 | 12.2 |

| COL+ | 49.3 | 50.7 | 47.1 | 38.8 | 44.7 | 53.9 | 72.6 | 45.6 | 21.2 | 32.9 | 34.3 | 27.2 | 18.0 | |

| p-value | 0.547 | 0.783 | 0.176 | 0.041 | 0.291 | 0.975 | 0.846 | 0.009 | 0.655 | 0.384 | 0.005 | 0.102 | 0.181 | |

| Wheat flour | ≤HS | 68.9 | 86.7 | 57.7 | 75.3 | 69.0 | 65.3 | 85.7 | 42.5 | 56.7 | 71.4 | 75.4 | 76.4 | 70.0 |

| COL+ | 63.6 | 86.0 | 63.2 | 69.9 | 67.8 | 60.7 | 92.5 | 42.6 | 72.0 | 64.6 | 75.9 | 71.6 | 73.7 | |

| p-value | 0.168 | 0.922 | 0.170 | 0.147 | 0.755 | 0.235 | 0.076 | 0.977 | 0.001 | 0.461 | 0.930 | 0.172 | 0.463 | |

| Xanthan gum | ≤HS | 6.0 | 6.7 | 0.5 | 5.2 | 7.8 | 8.8 | 5.4 | 15.8 | 9.7 | 35.7 | 34.4 | 10.8 | 7.8 |

| COL+ | 10.8 | 4.7 | 2.0 | 9.3 | 11.9 | 7.7 | 4.7 | 16.7 | 16.9 | 30.9 | 19.9 | 15.0 | 10.0 | |

| p-value | 0.037 | 0.615 | 0.128 | 0.066 | 0.092 | 0.616 | 0.827 | 0.769 | 0.040 | 0.591 | 0.008 | 0.122 | 0.510 |

| Ingredient | Sex | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | India | Japan | South Africa | United Kingdom | USA | Russia | Brazil | China | Mexico | Peru | Spain | Thailand | ||

| Baking soda | Male | 20.0 | 14.3 | 1.3 | 13.0 | 22.6 | 31.8 | 4.8 | 16.5 | 17.1 | 16.2 | 5.4 | 13.3 | 4.4 |

| Female | 21.9 | 15.5 | 2.2 | 12.7 | 19.3 | 34.5 | 10.8 | 19.7 | 15.6 | 20.6 | 7.3 | 23.5 | 6.7 | |

| p-value | 0.557 | 0.667 | 0.362 | 0.906 | 0.308 | 0.481 | 0.005 | 0.301 | 0.591 | 0.151 | 0.328 | 0.001 | 0.224 | |

| BHA | Male | 2.9 | 3.2 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 5.1 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 1.3 |

| Female | 1.6 | 2.8 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 0.3 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| p-value | 0.280 | 0.811 | 0.319 | 1.000 | 0.531 | 0.093 | 0.319 | 0.362 | 0.008 | 0.738 | 0.045 | 0.317 | 0.705 | |

| Black beans | Male | 58.7 | 57.1 | 60.3 | 67.9 | 63.4 | 62.4 | 64.4 | 8.3 | 14.0 | 22.9 | 6.7 | 33.3 | 1.6 |

| Female | 64.1 | 52.2 | 64.8 | 68.3 | 68.0 | 63.0 | 66.0 | 7.9 | 10.5 | 25.4 | 14.0 | 38.7 | 0.6 | |

| p-value | 0.165 | 0.214 | 0.250 | 0.932 | 0.218 | 0.886 | 0.676 | 0.884 | 0.181 | 0.457 | 0.003 | 0.159 | 0.255 | |

| Canola oil | Male | 48.9 | 33.0 | 27.0 | 61.0 | 27.4 | 43.0 | 9.8 | 47.3 | 51.4 | 38.7 | 27.3 | 10.8 | 18.7 |

| Female | 37.8 | 35.4 | 28.9 | 61.0 | 27.8 | 40.8 | 9.5 | 42.9 | 54.3 | 42.5 | 33.0 | 11.4 | 25.7 | |

| p-value | 0.005 | 0.521 | 0.595 | 1.000 | 0.898 | 0.581 | 0.893 | 0.263 | 0.473 | 0.331 | 0.119 | 0.800 | 0.035 | |

| Corn | Male | 76.2 | 84.4 | 61.0 | 80.3 | 73.2 | 73.9 | 81.9 | 87.6 | 73.3 | 92.1 | 91.7 | 80.6 | 2.9 |

| Female | 82.9 | 81.3 | 62.2 | 73.7 | 71.2 | 64.2 | 87.9 | 79.0 | 76.2 | 92.4 | 87.3 | 79.7 | 3.5 | |

| p-value | 0.038 | 0.299 | 0.744 | 0.047 | 0.567 | 0.009 | 0.035 | 0.004 | 0.410 | 0.882 | 0.069 | 0.765 | 0.650 | |

| Corn syrup | Male | 23.5 | 23.5 | 9.8 | 27.9 | 29.6 | 24.2 | 26.0 | 26.7 | 25.4 | 49.5 | 35.6 | 45.4 | 49.8 |

| Female | 20.6 | 20.3 | 8.6 | 24.8 | 25.0 | 14.9 | 27.9 | 18.4 | 30.2 | 43.2 | 30.2 | 43.8 | 47.0 | |

| p-value | 0.388 | 0.326 | 0.582 | 0.366 | 0.194 | 0.003 | 0.591 | 0.013 | 0.183 | 0.110 | 0.150 | 0.689 | 0.474 | |

| Gluten | Male | 25.4 | 11.7 | 13.3 | 19.7 | 31.8 | 25.5 | 7.0 | 12.7 | 27.3 | 11.7 | 16.5 | 20.0 | 6.0 |

| Female | 27.0 | 13.6 | 13.7 | 22.9 | 31.6 | 20.6 | 13.0 | 10.5 | 29.2 | 17.1 | 15.6 | 28.3 | 8.6 | |

| p-value | 0.651 | 0.483 | 0.908 | 0.331 | 0.957 | 0.144 | 0.012 | 0.384 | 0.596 | 0.054 | 0.745 | 0.016 | 0.221 | |

| Insect powder | Male | 6.3 | 4.1 | 18.4 | 5.1 | 8.6 | 8.6 | 16.2 | 14.9 | 10.5 | 27.0 | 8.3 | 9.5 | 9.2 |

| Female | 3.2 | 4.7 | 13.3 | 2.2 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 20.0 | 9.5 | 17.8 | 28.6 | 6.0 | 12.1 | 7.9 | |

| p-value | 0.062 | 0.706 | 0.081 | 0.056 | 0.158 | 0.158 | 0.215 | 0.039 | 0.009 | 0.657 | 0.279 | 0.305 | 0.570 | |

| Lecithin | Male | 19.4 | 6.3 | 5.4 | 14.6 | 11.8 | 16.9 | 9.8 | 2.5 | 7.3 | 2.2 | 0.6 | 4.8 | 1.6 |

| Female | 23.5 | 5.4 | 6.3 | 17.1 | 14.2 | 10.4 | 20.6 | 7.0 | 7.6 | 5.4 | 1.0 | 3.8 | 0.3 | |

| p-value | 0.207 | 0.605 | 0.612 | 0.384 | 0.360 | 0.019 | 0.000 | 0.009 | 0.880 | 0.038 | 0.655 | 0.556 | 0.101 | |

| Maltodextrins | Male | 8.3 | 3.5 | 1.0 | 3.8 | 5.4 | 6.7 | 3.2 | 40.0 | 42.5 | 19.4 | 71.7 | 30.8 | 66.3 |

| Female | 4.8 | 4.1 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 5.7 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 37.8 | 41.9 | 22.9 | 69.5 | 37.1 | 63.8 | |

| p-value | 0.076 | 0.684 | 0.315 | 0.245 | 0.878 | 0.013 | 0.462 | 0.568 | 0.872 | 0.283 | 0.541 | 0.093 | 0.504 | |

| Molasses | Male | 38.1 | 25.1 | 32.4 | 45.1 | 37.9 | 46.2 | 8.6 | 2.9 | 8.3 | 2.5 | 1.3 | 3.5 | 0.6 |

| Female | 40.6 | 22.5 | 41.3 | 44.1 | 41.1 | 44.0 | 7.6 | 3.5 | 10.8 | 1.3 | 2.9 | 0.6 | 1.6 | |

| p-value | 0.515 | 0.442 | 0.021 | 0.810 | 0.406 | 0.581 | 0.662 | 0.650 | 0.278 | 0.244 | 0.162 | 0.012 | 0.255 | |

| Pea flour | Male | 39.0 | 49.8 | 31.1 | 48.3 | 40.4 | 40.8 | 67.0 | 81.9 | 66.3 | 88.3 | 80.0 | 48.9 | 87.9 |

| Female | 37.8 | 49.4 | 28.9 | 52.1 | 43.4 | 35.4 | 71.4 | 73.0 | 67.0 | 85.1 | 80.6 | 45.7 | 88.6 | |

| p-value | 0.744 | 0.905 | 0.543 | 0.339 | 0.460 | 0.169 | 0.227 | 0.008 | 0.866 | 0.242 | 0.842 | 0.452 | 0.805 | |

| Salt | Male | 61.0 | 66.7 | 51.1 | 62.2 | 57.3 | 56.1 | 79.7 | 42.2 | 32.1 | 59.7 | 47.9 | 64.8 | 92.1 |

| Female | 54.9 | 57.9 | 48.6 | 51.7 | 51.6 | 52.8 | 76.5 | 28.3 | 34.0 | 54.3 | 48.6 | 60.6 | 95.2 | |

| p-value | 0.126 | 0.023 | 0.524 | 0.008 | 0.148 | 0.420 | 0.336 | 0.000 | 0.612 | 0.172 | 0.874 | 0.285 | 0.103 | |

| SAPP | Male | 3.2 | 5.1 | 1.0 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 4.1 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.6 |

| Female | 2.2 | 2.8 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 1.0 | 3.2 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 2.5 | |

| p-value | 0.462 | 0.151 | 0.478 | 0.105 | 0.804 | 0.169 | 0.478 | 0.192 | 0.590 | 0.056 | 0.317 | 0.705 | 0.056 | |

| Sodium bicarbonate | Male | 18.4 | 5.1 | 3.5 | 12.1 | 16.2 | 15.6 | 43.8 | 9.8 | 6.7 | 19.7 | 9.8 | 9.8 | 4.4 |

| Female | 20.6 | 7.0 | 4.1 | 9.8 | 16.8 | 10.4 | 48.9 | 11.1 | 5.7 | 30.5 | 16.5 | 16.8 | 3.2 | |

| p-value | 0.482 | 0.321 | 0.678 | 0.372 | 0.858 | 0.054 | 0.202 | 0.603 | 0.621 | 0.002 | 0.013 | 0.010 | 0.406 | |

| Sorghum flour | Male | 39.0 | 28.3 | 1.9 | 53.7 | 18.5 | 27.7 | 30.5 | 22.5 | 61.0 | 40.0 | 25.7 | 18.1 | 65.4 |

| Female | 33.7 | 25.3 | 2.2 | 37.1 | 11.7 | 20.3 | 33.7 | 14.0 | 59.7 | 30.8 | 19.0 | 23.5 | 61.3 | |

| p-value | 0.160 | 0.405 | 0.780 | <0.0001 | 0.018 | 0.029 | 0.394 | 0.005 | 0.745 | 0.016 | 0.045 | 0.095 | 0.283 | |

| Soybean | Male | 71.4 | 84.8 | 71.7 | 72.4 | 56.1 | 60.8 | 40.3 | 83.2 | 68.6 | 57.5 | 68.3 | 65.1 | 93.3 |

| Female | 66.3 | 78.8 | 71.4 | 67.3 | 61.7 | 62.3 | 42.2 | 79.0 | 65.4 | 66.3 | 71.1 | 74.9 | 94.9 | |

| p-value | 0.169 | 0.053 | 0.930 | 0.165 | 0.149 | 0.697 | 0.628 | 0.186 | 0.397 | 0.022 | 0.436 | 0.007 | 0.398 | |

| Sugar | Male | 53.7 | 57.8 | 48.6 | 48.3 | 51.9 | 57.3 | 75.9 | 40.3 | 19.7 | 31.7 | 34.6 | 20.3 | 16.8 |

| Female | 47.0 | 44.0 | 41.6 | 35.6 | 40.8 | 50.3 | 69.2 | 42.2 | 21.9 | 33.3 | 30.5 | 28.9 | 17.5 | |

| p-value | 0.095 | 0.001 | 0.078 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.078 | 0.061 | 0.628 | 0.492 | 0.671 | 0.269 | 0.013 | 0.833 | |

| Wheat flour | Male | 66.7 | 88.9 | 65.4 | 78.1 | 71.7 | 66.6 | 93.0 | 52.4 | 67.9 | 72.1 | 79.0 | 73.0 | 76.8 |

| Female | 64.8 | 83.2 | 57.1 | 65.7 | 64.9 | 59.2 | 90.8 | 32.7 | 69.5 | 57.8 | 72.7 | 74.6 | 69.5 | |

| p-value | 0.615 | 0.040 | 0.034 | 0.001 | 0.068 | 0.055 | 0.307 | <0.0001 | 0.668 | 0.000 | 0.063 | 0.651 | 0.039 | |

| Xanthan gum | Male | 9.5 | 5.1 | 1.0 | 9.5 | 9.9 | 10.2 | 2.5 | 17.5 | 14.0 | 30.8 | 19.0 | 10.8 | 12.1 |

| Female | 8.3 | 4.4 | 1.9 | 6.0 | 10.8 | 6.3 | 7.0 | 15.2 | 16.8 | 31.4 | 23.5 | 15.2 | 7.3 | |

| p-value | 0.576 | 0.702 | 0.315 | 0.102 | 0.715 | 0.079 | 0.009 | 0.451 | 0.321 | 0.864 | 0.173 | 0.098 | 0.044 |

| Ingredient | No. of Adults | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | India | Japan | South Africa | United Kingdom | USA | Russia | Brazil | China | Mexico | Peru | Spain | Thailand | ||

| Baking soda | 1–2 | 21.8 | 16.8 | 1.5 | 13.4 | 22.9 | 31.6 | 7.7 | 18.6 | 14.0 | 23.1 | 3.8 | 17.5 | 5.8 |

| 3+ | 18.4 | 17.0 | 2.0 | 12.1 | 14.8 | 37.9 | 7.9 | 17.5 | 14.2 | 18.13 | 6.5 | 18.5 | 5.5 | |

| p-value | 0.379 | 0.933 | 0.613 | 0.618 | 0.031 | 0.141 | 0.954 | 0.733 | 0.951 | 0.439 | 0.594 | 0.838 | 0.884 | |

| BHA | 1–2 | 2.5 | 4.6 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 1.9 | 3.8 | 0.0 | 1.8 | 0.7 | 2.6 | 3.8 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| 3+ | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 3.7 | 0.4 | 1.7 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 1.1 | |

| p-value | 0.385 | 0.008 | 0.290 | 0.694 | 0.281 | 0.950 | 0.187 | 0.869 | 0.205 | 0.539 | 0.036 | 0.506 | 0.921 | |

| Black beans | 1–2 | 62.8 | 55.5 | 61.7 | 71.2 | 67.6 | 64.0 | 63.1 | 8.8 | 14.7 | 30.8 | 3.8 | 36.5 | 1.6 |

| 3+ | 57.2 | 11.5 | 63.5 | 63.8 | 60.0 | 59.0 | 69.0 | 7.3 | 54.4 | 23.7 | 0.5 | 36.0 | 0.9 | |

| p-value | 0.223 | <0.0001 | 0.635 | 0.048 | 0.085 | 0.262 | 0.135 | 0.475 | <0.0001 | 0.318 | 0.269 | 0.934 | 0.469 | |

| Canola oil | 1–2 | 45.2 | 34.7 | 26.0 | 59.5 | 26.9 | 42.2 | 9.7 | 43.6 | 51.0 | 43.6 | 23.1 | 6.3 | 19.9 |

| 3+ | 37.5 | 53.4 | 30.1 | 63.0 | 29.7 | 41.0 | 9.6 | 46.7 | 34.1 | 40.4 | 30.5 | 11.6 | 23.2 | |

| p-value | 0.096 | <0.0001 | 0.262 | 0.366 | 0.510 | 0.786 | 0.962 | 0.436 | 0.000 | 0.699 | 0.422 | 0.205 | 0.355 | |

| Corn | 1–2 | 79.9 | 80.9 | 59.6 | 76.2 | 74.1 | 69.9 | 85.5 | 84.5 | 66.4 | 92.3 | 84.6 | 73.0 | 2.1 |

| 3+ | 78.3 | 77.2 | 63.9 | 78.1 | 66.5 | 66.5 | 83.8 | 82.1 | 83.6 | 92.2 | 89.7 | 81.0 | 3.6 | |

| p-value | 0.666 | 0.310 | 0.272 | 0.567 | 0.065 | 0.411 | 0.568 | 0.433 | <0.0001 | 0.984 | 0.405 | 0.134 | 0.308 | |

| Corn syrup | 1–2 | 23.6 | 17.9 | 7.8 | 28.2 | 28.4 | 20.3 | 25.7 | 26.8 | 23.8 | 53.8 | 30.8 | 47.6 | 50.3 |

| 3+ | 17.1 | 29.0 | 10.8 | 23.8 | 23.9 | 17.4 | 29.3 | 17.9 | 23.4 | 45.9 | 32.9 | 44.3 | 47.6 | |

| p-value | 0.091 | 0.005 | 0.190 | 0.212 | 0.270 | 0.429 | 0.332 | 0.007 | 0.919 | 0.333 | 0.818 | 0.612 | 0.541 | |

| Gluten | 1–2 | 26.8 | 14.5 | 12.9 | 24.4 | 32.0 | 24.1 | 10.0 | 12.2 | 25.9 | 23.1 | 11.5 | 27.0 | 4.7 |

| 3+ | 24.3 | 29.0 | 14.2 | 17.0 | 31.0 | 19.9 | 10.0 | 10.9 | 12.0 | 13.9 | 16.2 | 23.8 | 8.4 | |

| p-value | 0.552 | 0.000 | 0.630 | 0.025 | 0.811 | 0.273 | 0.978 | 0.620 | <0.0001 | 0.114 | 0.525 | 0.577 | 0.100 | |

| Insect powder | 1–2 | 4.4 | 5.2 | 14.4 | 3.3 | 8.8 | 8.1 | 17.7 | 11.0 | 11.2 | 23.1 | 7.7 | 14.3 | 6.8 |

| 3+ | 5.9 | 15.0 | 17.6 | 4.2 | 1.9 | 4.3 | 18.8 | 13.6 | 4.1 | 28.1 | 7.1 | 10.4 | 9.3 | |

| p-value | 0.442 | 0.001 | 0.274 | 0.569 | 0.004 | 0.111 | 0.737 | 0.320 | 0.002 | 0.499 | 0.913 | 0.347 | 0.297 | |

| Lecithin | 1–2 | 22.6 | 6.9 | 7.2 | 18.6 | 14.7 | 14.3 | 15.2 | 4.3 | 5.6 | 2.6 | 0.0 | 3.2 | 2.1 |

| 3+ | 17.8 | 8.0 | 4.4 | 12.1 | 7.7 | 11.8 | 15.3 | 5.3 | 5.5 | 3.9 | 0.8 | 4.4 | 0.5 | |

| p-value | 0.207 | 0.651 | 0.137 | 0.026 | 0.025 | 0.429 | 0.981 | 0.545 | 0.951 | 0.676 | 0.644 | 0.647 | 0.052 | |

| Maltodextrins | 1–2 | 6.1 | 3.5 | 1.8 | 3.8 | 6.5 | 4.9 | 2.0 | 39.3 | 30.8 | 23.1 | 57.7 | 39.7 | 62.8 |

| 3+ | 7.9 | 45.6 | 1.0 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 38.4 | 3.9 | 21.0 | 71.2 | 33.3 | 66.1 | |

| p-value | 0.427 | <0.0001 | 0.410 | 0.159 | 0.063 | 0.539 | 0.150 | 0.814 | <0.0001 | 0.757 | 0.139 | 0.313 | 0.435 | |

| Molasses | 1–2 | 41.8 | 24.3 | 35.6 | 46.0 | 43.6 | 46.3 | 9.0 | 2.7 | 8.4 | 2.6 | 3.8 | 1.6 | 0.5 |

| 3+ | 31.6 | 9.9 | 38.2 | 42.6 | 27.1 | 41.6 | 6.6 | 3.6 | 23.6 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 1.4 | |

| p-value | 0.024 | <0.0001 | 0.509 | 0.399 | 0.000 | 0.306 | 0.283 | 0.521 | <0.0001 | 0.757 | 0.516 | 0.781 | 0.354 | |

| Pea flour | 1–2 | 38.9 | 49.7 | 31.4 | 52.3 | 43.8 | 40.5 | 67.6 | 78.7 | 55.2 | 84.6 | 69.2 | 49.2 | 86.9 |

| 3+ | 36.8 | 70.0 | 28.4 | 47.2 | 36.1 | 31.1 | 72.1 | 76.2 | 49.6 | 86.8 | 80.8 | 47.1 | 88.8 | |

| p-value | 0.648 | <0.0001 | 0.404 | 0.202 | 0.094 | 0.033 | 0.243 | 0.454 | 0.236 | 0.698 | 0.147 | 0.750 | 0.490 | |

| Salt | 1–2 | 60.5 | 65.9 | 50.9 | 57.0 | 57.9 | 54.8 | 77.6 | 36.9 | 25.9 | 48.7 | 38.5 | 58.7 | 90.1 |

| 3+ | 50.0 | 35.1 | 48.6 | 57.0 | 43.9 | 53.4 | 79.0 | 33.4 | 60.9 | 57.5 | 48.7 | 63.1 | 95.2 | |

| p-value | 0.023 | <0.0001 | 0.573 | 0.999 | 0.002 | 0.762 | 0.666 | 0.366 | <0.0001 | 0.282 | 0.308 | 0.493 | 0.015 | |

| SAPP | 1–2 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 2.1 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 3.4 | 0.5 | 2.7 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.6 | 2.6 |

| 3+ | 1.3 | 2.7 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.0 | 4.1 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.1 | |

| p-value | 0.228 | 0.590 | 0.050 | 0.302 | 0.306 | 0.564 | 0.022 | 0.534 | 0.045 | 0.414 | 0.680 | 0.706 | 0.173 | |

| Sodium bicarbonate | 1–2 | 20.7 | 5.2 | 3.0 | 13.4 | 17.9 | 14.5 | 45.4 | 10.7 | 4.2 | 38.5 | 23.1 | 19.0 | 4.7 |

| 3+ | 15.8 | 6.8 | 4.7 | 7.5 | 12.3 | 8.7 | 48.0 | 10.3 | 6.3 | 24.2 | 12.7 | 12.7 | 3.4 | |

| p-value | 0.183 | 0.467 | 0.257 | 0.020 | 0.101 | 0.059 | 0.522 | 0.868 | 0.342 | 0.047 | 0.128 | 0.160 | 0.436 | |

| Sorghum flour | 1–2 | 39.3 | 28.9 | 2.4 | 45.8 | 16.0 | 25.4 | 32.9 | 17.4 | 49.7 | 33.3 | 11.5 | 17.5 | 57.1 |

| 3+ | 27.0 | 63.4 | 1.7 | 44.9 | 12.3 | 19.9 | 30.6 | 19.2 | 26.0 | 35.5 | 22.8 | 21.2 | 66.1 | |

| p-value | 0.006 | <0.0001 | 0.535 | 0.833 | 0.259 | 0.159 | 0.544 | 0.554 | <0.0001 | 0.781 | 0.176 | 0.493 | 0.032 | |

| Soybean | 1–2 | 70.5 | 78.6 | 70.4 | 69.3 | 62.3 | 62.5 | 42.4 | 81.1 | 53.1 | 69.2 | 76.9 | 65.1 | 92.7 |

| 3+ | 63.8 | 71.0 | 73.0 | 70.6 | 48.4 | 59.0 | 39.3 | 81.1 | 83.0 | 61.4 | 69.4 | 70.5 | 94.8 | |

| p-value | 0.121 | 0.054 | 0.468 | 0.736 | 0.002 | 0.436 | 0.449 | 0.993 | <0.0001 | 0.331 | 0.413 | 0.370 | 0.306 | |

| Sugar | 1–2 | 52.3 | 50.9 | 44.6 | 41.4 | 49.3 | 54.6 | 71.6 | 43.0 | 16.8 | 35.9 | 26.9 | 23.8 | 18.8 |

| 3+ | 44.1 | 22.0 | 45.6 | 42.6 | 37.4 | 51.6 | 74.2 | 39.4 | 50.9 | 32.3 | 32.8 | 24.7 | 16.4 | |

| p-value | 0.078 | <0.0001 | 0.802 | 0.750 | 0.010 | 0.506 | 0.472 | 0.362 | <0.0001 | 0.645 | 0.533 | 0.878 | 0.454 | |

| Wheat flour | 1–2 | 67.8 | 90.2 | 59.9 | 70.1 | 68.6 | 63.5 | 91.0 | 43.9 | 58.7 | 74.4 | 69.2 | 77.8 | 70.7 |

| 3+ | 59.2 | 71.7 | 62.8 | 74.3 | 67.1 | 60.9 | 93.4 | 41.1 | 84.5 | 64.3 | 76.2 | 73.4 | 74.3 | |

| p-value | 0.053 | <0.0001 | 0.447 | 0.247 | 0.722 | 0.546 | 0.283 | 0.471 | <0.0001 | 0.203 | 0.420 | 0.451 | 0.352 | |

| Xanthan gum | 1–2 | 9.2 | 3.5 | 1.8 | 8.2 | 11.6 | 9.2 | 4.5 | 18.0 | 11.2 | 35.9 | 19.2 | 7.9 | 7.3 |

| 3+ | 7.9 | 16.6 | 1.0 | 7.2 | 6.5 | 5.6 | 5.2 | 14.6 | 5.2 | 30.8 | 21.4 | 13.6 | 10.7 | |

| p-value | 0.622 | <0.0001 | 0.410 | 0.628 | 0.069 | 0.155 | 0.671 | 0.247 | 0.013 | 0.506 | 0.796 | 0.207 | 0.188 |

| Ingredient | No. of Children | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | India | Japan | South Africa | United Kingdom | USA | Russia | Brazil | China | Mexico | Peru | Spain | Thailand | ||

| Baking soda | None | 21.7 | 16.5 | 1.5 | 13.9 | 20.7 | 34.9 | 6.1 | 20.3 | 15.3 | 18.9 | 7.7 | 18.2 | 6.6 |

| 1+ | 19.4 | 13.8 | 2.5 | 11.7 | 21.4 | 29.6 | 9.5 | 15.3 | 17.1 | 18.1 | 5.5 | 18.7 | 4.6 | |

| p-value | 0.506 | 0.361 | 0.377 | 0.416 | 0.836 | 0.186 | 0.111 | 0.103 | 0.540 | 0.803 | 0.277 | 0.875 | 0.254 | |

| BHA | None | 2.1 | 2.7 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| 1+ | 2.4 | 3.2 | 0.0 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 4.9 | 0.3 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 1.8 | |

| p-value | 0.859 | 0.748 | 0.567 | 0.067 | 0.810 | 0.340 | 0.302 | 0.504 | 0.453 | 0.783 | 0.144 | 0.175 | 0.075 | |

| Black beans | None | 68.3 | 56.9 | 64.1 | 73.2 | 70.3 | 66.3 | 63.8 | 8.3 | 12.3 | 25.2 | 10.9 | 36.1 | 0.7 |

| 1+ | 47.9 | 53.2 | 58.0 | 62.2 | 57.6 | 55.3 | 66.8 | 7.8 | 12.2 | 23.5 | 9.9 | 35.9 | 1.5 | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.364 | 0.172 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.008 | 0.434 | 0.827 | 0.952 | 0.621 | 0.705 | 0.946 | 0.307 | |

| Canola oil | None | 47.5 | 33.7 | 28.3 | 59.9 | 27.2 | 42.2 | 10.1 | 44.1 | 49.6 | 37.4 | 27.0 | 10.3 | 22.9 |

| 1+ | 35.1 | 34.6 | 26.8 | 62.2 | 28.4 | 41.3 | 9.2 | 46.3 | 55.2 | 42.6 | 32.2 | 12.2 | 21.6 | |

| p-value | 0.003 | 0.826 | 0.703 | 0.553 | 0.746 | 0.820 | 0.699 | 0.592 | 0.163 | 0.197 | 0.167 | 0.458 | 0.686 | |

| Corn | None | 84.0 | 81.6 | 63.2 | 78.5 | 74.8 | 70.5 | 83.7 | 80.2 | 70.9 | 93.3 | 87.5 | 79.3 | 2.0 |

| 1+ | 70.6 | 83.8 | 56.7 | 75.3 | 67.7 | 66.0 | 86.2 | 87.2 | 77.6 | 91.6 | 90.8 | 81.3 | 4.3 | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.470 | 0.146 | 0.341 | 0.055 | 0.252 | 0.393 | 0.020 | 0.055 | 0.442 | 0.182 | 0.546 | 0.106 | |

| Corn syrup | None | 26.0 | 19.6 | 10.4 | 28.9 | 30.2 | 20.0 | 25.2 | 22.3 | 28.7 | 47.5 | 33.5 | 47.8 | 45.5 |

| 1+ | 14.2 | 23.4 | 5.7 | 23.4 | 22.3 | 18.4 | 28.9 | 22.8 | 27.1 | 45.7 | 32.5 | 40.1 | 51.1 | |

| p-value | 0.001 | 0.258 | 0.083 | 0.116 | 0.032 | 0.635 | 0.284 | 0.899 | 0.646 | 0.658 | 0.793 | 0.054 | 0.164 | |

| Gluten | None | 31.3 | 10.6 | 13.5 | 25.7 | 32.4 | 24.1 | 9.5 | 14.6 | 26.1 | 16.8 | 19.4 | 27.2 | 6.6 |

| 1+ | 16.1 | 14.1 | 13.4 | 16.2 | 30.6 | 20.9 | 10.5 | 7.8 | 29.8 | 13.0 | 13.9 | 19.8 | 7.9 | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.194 | 0.961 | 0.004 | 0.632 | 0.374 | 0.671 | 0.008 | 0.306 | 0.189 | 0.067 | 0.034 | 0.545 | |

| Insect powder | None | 3.3 | 3.1 | 16.1 | 2.4 | 7.0 | 7.3 | 19.6 | 12.9 | 11.9 | 31.5 | 7.7 | 10.3 | 7.0 |

| 1+ | 7.6 | 5.3 | 15.3 | 5.2 | 7.4 | 6.8 | 16.4 | 11.4 | 15.7 | 25.5 | 6.8 | 11.5 | 10.0 | |

| p-value | 0.018 | 0.192 | 0.817 | 0.063 | 0.837 | 0.814 | 0.300 | 0.567 | 0.176 | 0.103 | 0.685 | 0.655 | 0.172 | |

| Lecithin | None | 27.7 | 5.1 | 6.6 | 20.6 | 15.5 | 14.9 | 15.0 | 4.3 | 7.5 | 3.8 | 0.8 | 4.1 | 0.7 |

| 1+ | 9.0 | 6.4 | 3.8 | 10.3 | 8.7 | 11.2 | 15.5 | 5.3 | 7.5 | 3.8 | 0.8 | 4.6 | 1.2 | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.501 | 0.208 | 0.000 | 0.016 | 0.206 | 0.881 | 0.543 | 0.999 | 0.978 | 0.978 | 0.759 | 0.478 | |

| Maltodextrins | None | 6.9 | 2.7 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 6.5 | 4.7 | 2.5 | 38.4 | 37.7 | 20.2 | 70.2 | 35.3 | 65.4 |

| 1+ | 5.7 | 4.5 | 0.6 | 3.4 | 3.9 | 4.4 | 3.0 | 39.5 | 45.6 | 21.7 | 70.9 | 32.1 | 64.7 | |

| p-value | 0.554 | 0.253 | 0.336 | 0.568 | 0.179 | 0.846 | 0.696 | 0.777 | 0.048 | 0.652 | 0.834 | 0.394 | 0.853 | |

| Molasses | None | 47.7 | 28.2 | 36.6 | 53.4 | 45.9 | 47.2 | 8.9 | 3.2 | 11.2 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.6 | 0.0 |

| 1+ | 22.7 | 20.7 | 37.6 | 34.4 | 28.4 | 40.8 | 7.2 | 3.2 | 8.3 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 2.7 | 2.1 | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.030 | 0.821 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.131 | 0.446 | 0.972 | 0.220 | 0.749 | 0.947 | 0.366 | 0.011 | |

| Pea flour | None | 41.8 | 54.9 | 30.4 | 53.7 | 43.6 | 40.8 | 70.6 | 78.2 | 65.3 | 85.3 | 80.6 | 48.4 | 87.7 |

| 1+ | 31.8 | 46.0 | 28.7 | 46.0 | 38.9 | 32.5 | 67.8 | 76.5 | 67.7 | 87.5 | 80.1 | 45.8 | 88.8 | |

| p-value | 0.015 | 0.029 | 0.673 | 0.056 | 0.243 | 0.045 | 0.449 | 0.610 | 0.531 | 0.430 | 0.868 | 0.525 | 0.684 | |

| Salt | None | 62.3 | 66.3 | 50.3 | 60.2 | 57.6 | 54.5 | 79.1 | 37.8 | 32.8 | 58.4 | 52.4 | 63.9 | 92.7 |

| 1+ | 49.3 | 59.6 | 48.4 | 53.3 | 48.9 | 54.4 | 77.0 | 32.0 | 33.1 | 56.1 | 45.5 | 61.1 | 94.5 | |

| p-value | 0.002 | 0.089 | 0.679 | 0.081 | 0.035 | 0.979 | 0.512 | 0.131 | 0.934 | 0.576 | 0.092 | 0.476 | 0.345 | |

| SAPP | None | 2.4 | 3.1 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 1.0 |

| 1+ | 3.3 | 4.5 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 0.3 | 1.5 | 2.1 | |

| p-value | 0.497 | 0.383 | 0.409 | 0.170 | 0.401 | 0.795 | 0.003 | 0.492 | 0.107 | 0.885 | 0.144 | 0.402 | 0.257 | |

| Sodium bicarbonate | None | 22.7 | 5.5 | 4.0 | 12.4 | 18.7 | 14.4 | 45.7 | 11.5 | 4.1 | 25.6 | 16.1 | 14.9 | 3.3 |

| 1+ | 13.3 | 6.4 | 3.2 | 9.3 | 12.7 | 10.2 | 47.0 | 9.3 | 7.7 | 24.7 | 11.3 | 11.1 | 4.3 | |

| p-value | 0.005 | 0.644 | 0.638 | 0.213 | 0.050 | 0.143 | 0.738 | 0.369 | 0.062 | 0.804 | 0.078 | 0.159 | 0.542 | |

| Sorghum flour | None | 43.7 | 29.4 | 1.7 | 48.1 | 16.7 | 25.9 | 34.0 | 19.2 | 55.6 | 33.2 | 20.6 | 22.3 | 62.8 |

| 1+ | 21.8 | 25.0 | 3.2 | 42.3 | 12.2 | 19.9 | 29.9 | 17.1 | 63.8 | 36.7 | 23.6 | 18.7 | 63.8 | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.220 | 0.255 | 0.144 | 0.131 | 0.096 | 0.269 | 0.495 | 0.037 | 0.368 | 0.379 | 0.276 | 0.787 | |

| Soybean | None | 74.5 | 83.1 | 71.7 | 71.4 | 61.3 | 63.2 | 44.5 | 81.1 | 60.8 | 64.7 | 72.2 | 69.3 | 95.0 |

| 1+ | 57.8 | 80.9 | 71.3 | 68.0 | 54.6 | 58.3 | 37.8 | 81.1 | 71.5 | 60.2 | 68.1 | 71.0 | 93.3 | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.466 | 0.936 | 0.362 | 0.097 | 0.231 | 0.091 | 0.988 | 0.005 | 0.260 | 0.273 | 0.647 | 0.364 | |

| Sugar | None | 58.0 | 54.5 | 46.3 | 43.7 | 48.9 | 57.8 | 72.4 | 44.7 | 17.9 | 33.6 | 34.3 | 25.8 | 14.3 |

| 1+ | 35.1 | 48.4 | 41.4 | 39.9 | 41.9 | 45.6 | 72.7 | 37.0 | 22.9 | 31.9 | 31.4 | 22.9 | 19.8 | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.133 | 0.286 | 0.336 | 0.092 | 0.004 | 0.932 | 0.052 | 0.125 | 0.654 | 0.455 | 0.403 | 0.069 | |

| Wheat flour | None | 72.6 | 88.6 | 61.5 | 71.4 | 70.6 | 63.7 | 92.6 | 41.8 | 67.2 | 60.9 | 72.6 | 75.8 | 68.8 |

| 1+ | 52.1 | 84.3 | 60.5 | 72.5 | 64.2 | 61.2 | 91.1 | 43.4 | 69.9 | 67.3 | 78.0 | 71.0 | 77.2 | |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.125 | 0.822 | 0.755 | 0.098 | 0.541 | 0.485 | 0.690 | 0.466 | 0.102 | 0.120 | 0.175 | 0.017 | |

| Xanthan gum | None | 9.8 | 5.1 | 1.5 | 10.6 | 12.7 | 8.0 | 3.7 | 14.6 | 13.8 | 29.8 | 19.4 | 12.5 | 8.0 |

| 1+ | 7.1 | 4.5 | 1.3 | 4.5 | 6.1 | 8.7 | 5.9 | 18.5 | 16.6 | 31.9 | 22.5 | 13.7 | 11.2 | |

| p-value | 0.266 | 0.739 | 0.852 | 0.004 | 0.009 | 0.759 | 0.188 | 0.190 | 0.342 | 0.589 | 0.344 | 0.649 | 0.166 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, J.; Chambers, E., IV; Lee, J. Consumer Sensory Perceptions of Natural Ingredients: A Multi-Country Comparison. Foods 2025, 14, 1775. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14101775

Choi J, Chambers E IV, Lee J. Consumer Sensory Perceptions of Natural Ingredients: A Multi-Country Comparison. Foods. 2025; 14(10):1775. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14101775

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Jisoo, Edgar Chambers, IV, and Jeehyun Lee. 2025. "Consumer Sensory Perceptions of Natural Ingredients: A Multi-Country Comparison" Foods 14, no. 10: 1775. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14101775

APA StyleChoi, J., Chambers, E., IV, & Lee, J. (2025). Consumer Sensory Perceptions of Natural Ingredients: A Multi-Country Comparison. Foods, 14(10), 1775. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14101775