Bioactive Peptides from Fermented Foods: Production Approaches, Sources, and Potential Health Benefits

Abstract

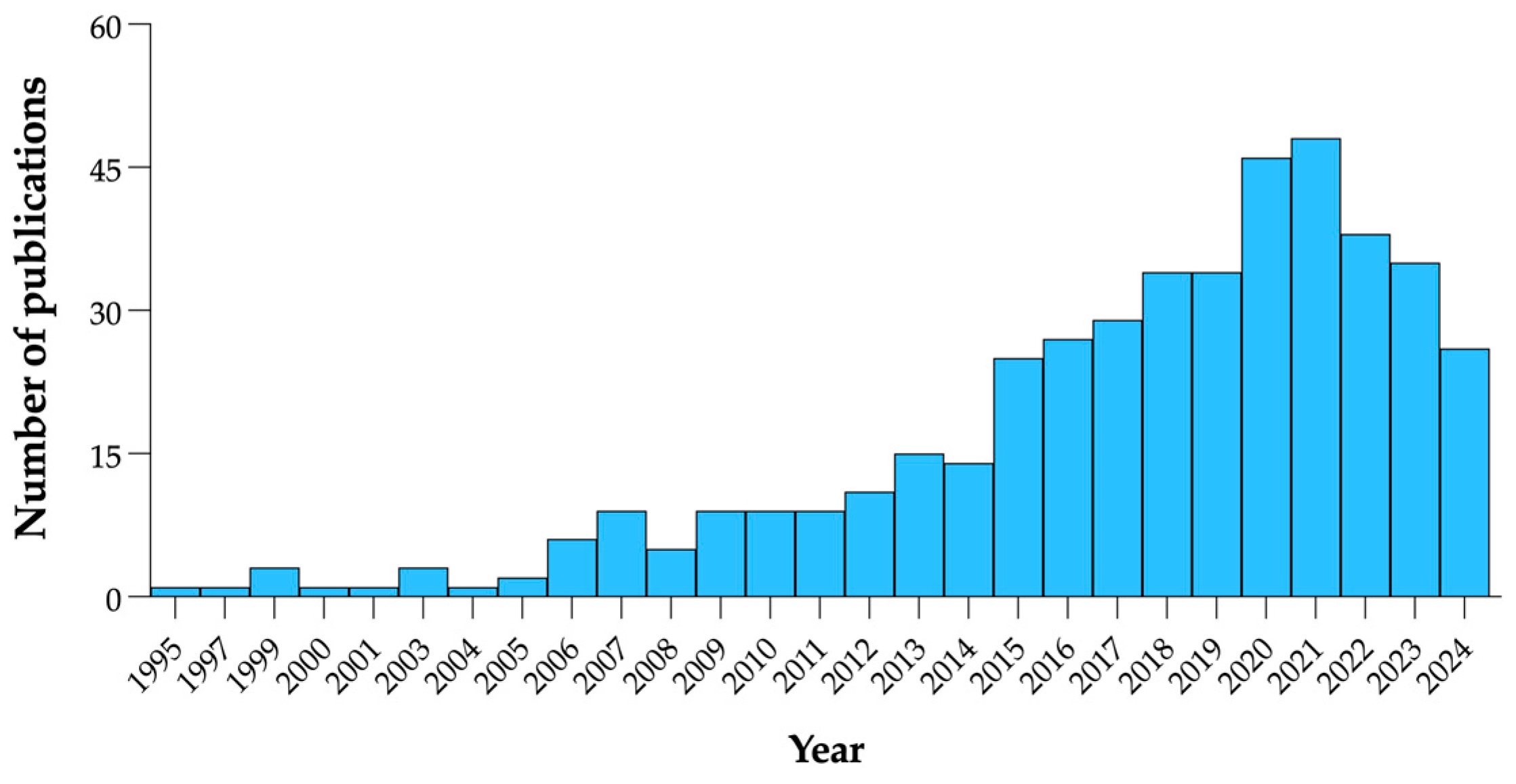

1. Introduction

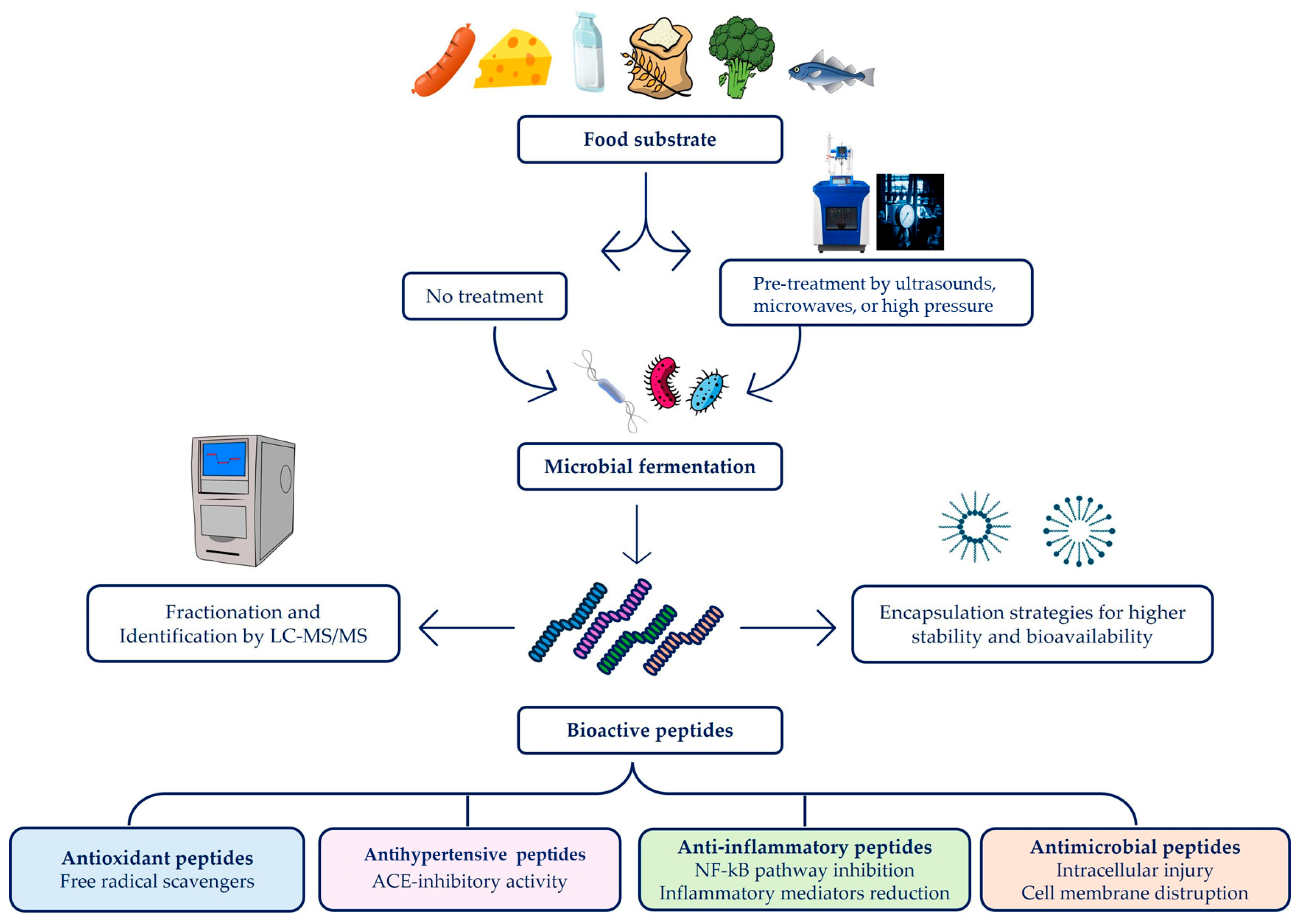

2. Fermentation Process for the Synthesis of BAPs

3. Fermented Foods as Sources of BAPs

3.1. Milk and Dairy Products

3.2. Meat

3.3. Plant-Based Foods

3.4. Marine Organisms

4. Bioactivities of BAPs Derived from Fermented Foods

4.1. Antimicrobial Activity

4.2. Antihypertensive Activity

4.3. Antioxidant Activity

4.4. Anti-Inflammatory Activity

| Fermented Food | Microorganisms | Fermentation Conditions | Peptide Sequence | Bioactivity | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milk | L. plantarum FB-2 | 37 °C for 20 h | KMYKKGRLWLVAGLS | Antimicrobial S. aureus and L. monocytogenes MIC = 256 μg/mL E. coli MIC = 128 μg/mL | [73] |

| Milk | L. helveticus CP790 and Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 37 °C for 24 h | VPP IPP | ACE-I IC50 = 9 μM IC50 = 5 μM | [110] |

| Milk | Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus NCDC24 | Not specified | AGWNIPM, ALPMHIR, VLPVPQKA YLGYLEQLLR | Antioxidant ABTS+ radical scavenging activity from 73.45 ± 0.57 (100 µg/mL) to 1.44 ± 0.22 (10 µg/mL) | [111] |

| Miso paste | Aspergillus oryzae | 30 °C for 40 h | VPP, IPP | Antihypertensive | [112] |

| Milk | Bifidobacterium bifidum MF20/5 | 37 °C for 48 h | VLPVPQK LVYPFP | Antioxidant ACE-I IC50 = 132 μM | [113] |

| Sator bean (Parkia speciosa) | L. fermentum ATCC9338 | 37 °C for 8 days | EAKPSFYLK PVNNNAWAYATNFVPGK | Antioxidant DPPH activity = 78.48 ± 3.16% Antibacterial activity S. typhi (73.41 ± 0.08%) and S. aureus (64.70 ± 1.10%) | [114] |

| Skimmed milk | Enterococcus faecalis CECT 5727 | 30 °C for 48 h | LHLPLP | Antihypertensive IC50 = 59.6 μg/mL | [115] |

| Dry fermented sausage | L. pentosus and Staphylococcus carnosus | Two stages: 20 °C for 22 h; 9 °C for 43 days | YQEPVLGPVR, YQEPVLGPVRGPFPI, YQEPLV | ACE-I IC50 = 300 µM | [48] |

| Avena (Avena sativa L.) | L. plantarum B1-6 and Rhizopus oryzae | 30 °C for 72 h | Not specified | ACE-I IC50 = 0.42 mg protein/mL | [55] |

| Lupin, quinoa, and wheat | L. reuteri K777 and L. plantarum K779 | 35 °C for 72 h | Not specified | ACE-I from 25.3% to 58.9% Antioxidant DPPH radical scavenging activities from 25.0% to 65.0% Antiproliferative | [56] |

| Wheat, soybean, Barley, and amaranth | L. curvatus SAL33 and L. brevis AM7 | 30 °C for 16 h | Lunasin (SKWQHQQDSCRKQLQGVNLTPCEKHIMEKIQGRGDDDDDDDDD) | Cancer preventive | [57] |

| Budu | Not specified | Over 120 days | VAAGRTDAGVH LDDPVFIH | Antioxidant DPPH radical scavenging activity IC50 = 1.451 ± 0.873 (mg/mL) IC50 = 0.844 ± 0.203 (mg/mL) | [63] |

| Zebra blenny (Salaria basilisca) muscle protein | Bacillus mojavensis A21 | From 4 to 48 h at 37 °C | GLPPYPYAG, LVDGLDVGIL, ETPGGTPLAPEPD, LSYEEAITTY, HHPDDFNPSVH | Antibacterial E. coli MIC = 0.62 ± 0.01 mg/mL K. pneumoniae MIC = 1.23 ± 0.02 mg/mL ACE-I Antioxidant | [62] |

| Pekasan (Loma fish) | L. plantarum IFRPD P15 | 2 weeks at RT | AIPPHPYP IAEVFLITDPK | Antioxidant activity DPPH radical scavenging activity IC50 (mg/mL) = 1.38 ± 0.25 IC50 (mg/mL) = 0.897 ± 0.84 | [64] |

| Manila clam (Ruditapes philippinarum) | Bacillus natto | 37 °C for 36 h | VISDEDGVTH | ACE-I IC50 = 8.16 μM | [18] |

| Thai shrimp pastes | Not specified | Not specified | SV, IF, WP | ACE-I IC50 = 60.68 ± 1.06 μM Antioxidant ABTS+ EC50 = 17.52 ± 0.46 μM | [65] |

| Kenaf seed | L. casei | 37 °C for 72 h | AKVGLKPGGFFVLK, GSTIK, LLLSK, TAHDDYK | Antibacterial activity from 42.07% to 77.38% | [116] |

| Tomato waste proteins | Bacillus subtilis | 37 °C for 24 h | DGVVYY GQVPP | ACE-I IC50 = 2 µM Antioxidant 97% DPPH scavenging activity at 0.4 mM | [92] |

| Cheddar cheese | L. helveticus and Streptococcus thermophilus | Not specified | EMPFPK, AVPYPQR, VLPVPQK, AMKPWIQPK | Antioxidant TEAC = 5.7 ± 0.6 mmol TE/mg | [97] |

| Feather hydrolysate | Bacillus subtilis S1-4 | 37 °C for 72 h | SNLCRPCG | Antioxidant DPPH IC50 = 0.39 mg/mL | [99] |

| Whey protein | L. rhamnosus B2-1 | 37 °C for 48 h | B11 | Antioxidant ABTS+ radical scavenging activities = 84.36% | [102] |

| Casein | L. reuteri | Not specified | VKEAMAPK | Antioxidant Decreased ROS activity by 45% | [101] |

| Broccoli | L. plantarum A3 and L. rhamnosus ATCC7469 | 37 °C for 24 h | SIWYGPDRP | Anti-inflammatory Inhibits NO release from inflammatory cells at 25 µM, with an inhibition rate of 52.32 ± 1.48 | [109] |

5. Challenges and Limitations in BAPs Production

6. Approaches for Enhancing BAP Production, Stability, and Bioavailability

6.1. Strategies to Optimize the Production of BAPs in Fermented Foods

6.2. Strategies to Improve the Stability and Bioavailability of BAPs

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marco, M.L.; Sanders, M.E.; Gänzle, M.; Arrieta, M.C.; Cotter, P.D.; De Vuyst, L.; Hill, C.; Holzapfel, W.; Lebeer, S.; Merenstein, D.; et al. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) Consensus Statement on Fermented Foods. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Burgos, M.; Moreno-Fernández, J.; Alférez, M.J.M.; Díaz-Castro, J.; López-Aliaga, I. New Perspectives in Fermented Dairy Products and Their Health Relevance. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 72, 104059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Ozaeta, I.; Astiazaran, O.J. Fermented Foods: An Update on Evidence-Based Health Benefits and Future Perspectives. Food Res. Int. 2022, 156, 111133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, H.; Pihlanto, A. Bioactive Peptides: Production and Functionality. Int. Dairy. J. 2006, 16, 945–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalamaiah, M.; Keskin Ulug, S.; Hong, H.; Wu, J. Regulatory Requirements of Bioactive Peptides (Protein Hydrolysates) from Food Proteins. J. Funct. Foods 2019, 58, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, M.; Shavandi, A.; Mirdamadi, S.; Soleymanzadeh, N.; Motahari, P.; Mirdamadi, N.; Moser, M.; Subra, G.; Alimoradi, H.; Goriely, S. Bioactive Peptides from Yeast: A Comparative Review on Production Methods, Bioactivity, Structure-Function Relationship, and Stability. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 118, 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, M.; Singh, J.; Gani, A. Exploration of Bioactive Peptides from Various Origin as Promising Nutraceutical Treasures: In Vitro, in Silico and in Vivo Studies. Food Chem. 2022, 373, 131395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Villaluenga, C.; Peñas, E.; Frias, J. Bioactive Peptides in Fermented Foods. In Fermented Foods in Health and Disease Prevention; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 23–47. [Google Scholar]

- Tadesse, S.A.; Emire, S.A. Production and Processing of Antioxidant Bioactive Peptides: A Driving Force for the Functional Food Market. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Sun, J.; Chandrapala, J.; Majzoobi, M.; Brennan, C.; Zeng, X.; Sun, B. Recent Progress of Food-derived Bioactive Peptides: Extraction, Purification, Function, and Encapsulation. Food Front. 2024, 5, 1240–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannaa, M.; Han, G.; Seo, Y.-S.; Park, I. Evolution of Food Fermentation Processes and the Use of Multi-Omics in Deciphering the Roles of the Microbiota. Foods 2021, 10, 2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, L. Impact of Sourdough Fermentation on Nutrient Transformations in Cereal-Based Foods: Mechanisms, Practical Applications, and Health Implications. Grain Oil Sci. Technol. 2024, 7, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.N.; Morawicki, R.O. Effects of Fermentation by Yeast and Amylolytic Lactic Acid Bacteria on Grain Sorghum Protein Content and Digestibility. J. Food Qual. 2018, 2018, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkhata, S.G.; Ayua, E.; Kamau, E.H.; Shingiro, J. Fermentation and Germination Improve Nutritional Value of Cereals and Legumes through Activation of Endogenous Enzymes. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 2446–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulug, S.K.; Jahandideh, F.; Wu, J. Novel Technologies for the Production of Bioactive Peptides. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 108, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Ledesma, B.; del Mar Contreras, M.; Recio, I. Antihypertensive Peptides: Production, Bioavailability and Incorporation into Foods. Adv. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2011, 165, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Sharma, N.; Sharma, S.; Samurailatpam, S.; Padhi, S.; Singh, S.P.; Kumar Rai, A. Production and Characterization of Bioactive Peptides in Fermented Soybean Meal Produced Using Proteolytic Bacillus Species Isolated from Kinema. Food Chem. 2023, 421, 136130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gao, X.; Wei, Y.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Ulaah, S. Isolation, Purification and the Anti-Hypertensive Effect of a Novel Angiotensin I-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitory Peptide from Ruditapes philippinarum Fermented with Bacillus natto. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 5230–5237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Juhász, A.; Bose, U.; Shiferaw Terefe, N.; Colgrave, M.L. Research Trends in Production, Separation, and Identification of Bioactive Peptides from Fungi—A Critical Review. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 119, 106343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, D.; Ma, J.; Xu, M.; Agyei, D. Cell-envelope Proteinases from Lactic Acid Bacteria: Biochemical Features and Biotechnological Applications. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 369–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raveschot, C.; Cudennec, B.; Coutte, F.; Flahaut, C.; Fremont, M.; Drider, D.; Dhulster, P. Production of Bioactive Peptides by Lactobacillus Species: From Gene to Application. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadat-Mekmene, L.; Jardin, J.; Corre, C.; Mollé, D.; Richoux, R.; Delage, M.-M.; Lortal, S.; Gagnaire, V. Simultaneous Presence of PrtH and PrtH2 Proteinases in Lactobacillus helveticus Strains Improves Breakdown of the Pure αs1-Casein. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto, M.; Ueno, H.M.; Watanabe, M.; Tatsuma, Y.; Seto, Y.; Miyamoto, T.; Nakajima, H. Distinctive Proteolytic Activity of Cell Envelope Proteinase of Lactobacillus helveticus Isolated from Airag, a Traditional Mongolian Fermented Mare’s Milk. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 197, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Casas, D.E.; Aguilar, C.N.; Ascacio-Valdés, J.A.; Rodríguez-Herrera, R.; Chávez-González, M.L.; Flores-Gallegos, A.C. Enzymatic Hydrolysis and Microbial Fermentation: The Most Favorable Biotechnological Methods for the Release of Bioactive Peptides. Food Chem. Mol. Sci. 2021, 3, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melini, F.; Melini, V.; Luziatelli, F.; Ficca, A.G.; Ruzzi, M. Health-Promoting Components in Fermented Foods: An Up-to-Date Systematic Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmisthaben, P.; Basaiawmoit, B.; Sakure, A.; Das, S.; Maurya, R.; Bishnoi, M.; Kondepudi, K.K.; Hati, S. Exploring Potentials of Antioxidative, Anti-Inflammatory Activities and Production of Bioactive Peptides in Lactic Fermented Camel Milk. Food Biosci. 2021, 44, 101404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wu, J.; Wan, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Q. Extraction and Identification of Bioactive Peptides from Panxian Dry-Cured Ham with Multifunctional Activities. LWT 2022, 160, 113326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folliero, V.; Lama, S.; Franci, G.; Giugliano, R.; D’Auria, G.; Ferranti, P.; Pourjula, M.; Galdiero, M.; Stiuso, P. Casein-Derived Peptides from the Dairy Product Kashk Exhibit Wound Healing Properties and Antibacterial Activity against Staphylococcus aureus: Structural and Functional Characterization. Food Res. Int. 2022, 153, 110949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, M.; Aida, R.; Saito, K.; Ochiai, A.; Takesono, S.; Saitoh, E.; Tanaka, T. Identification and Characterization of Multifunctional Cationic Peptides from Traditional Japanese Fermented Soybean Natto Extracts. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2019, 127, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, M.; Mora, L.; Toldrá, F. Characterisation of the Antioxidant Peptide AEEEYPDL and Its Quantification in Spanish Dry-Cured Ham. Food Chem. 2018, 258, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, B.F.; Zougman, A.; Masse, R.; Mulligan, C. Production and Characterization of Bioactive Peptides from Soy Hydrolysate and Soy-Fermented Food. Food Res. Int. 2004, 37, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasri, R.; Abdelhedi, O.; Nasri, M.; Jridi, M. Fermented Protein Hydrolysates: Biological Activities and Applications. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2022, 43, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, A.; Vázquez, A. Bioactive Peptides: A Review. Food Qual. Saf. 2017, 1, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsermoula, P.; Khakimov, B.; Nielsen, J.H.; Engelsen, S.B. WHEY—The Waste-Stream That Became More Valuable than the Food Product. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 118, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, B.; Athira, S.; Sharma, R.; Bajaj, R. Bioactive Peptides in Yogurt. In Yogurt in Health and Disease Prevention; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 411–426. [Google Scholar]

- Chourasia, R.; Abedin, M.M.; Chiring Phukon, L.; Sahoo, D.; Singh, S.P.; Rai, A.K. Biotechnological Approaches for the Production of Designer Cheese with Improved Functionality. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 960–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maïworé, J.; Tatsadjieu Ngoune, L.; Piro-Metayer, I.; Montet, D. Identification of Yeasts Present in Artisanal Yoghurt and Traditionally Fermented Milks Consumed in the Northern Part of Cameroon. Sci. Afr. 2019, 6, e00159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dullius, A.; Rama, G.R.; Giroldi, M.; Goettert, M.I.; Lehn, D.N.; Volken de Souza, C.F. Bioactive Peptide Production in Fermented Foods. In Current Developments in Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 47–72. [Google Scholar]

- Padhi, S.; Sharma, S.; Sahoo, D.; Montet, D.; Rai, A.K. Potential of Lactic Acid Bacteria as Starter Cultures for Food Fermentation and as Producers of Biochemicals for Value Addition. In Lactic Acid Bacteria in Food Biotechnology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 281–304. [Google Scholar]

- Martini, S.; Conte, A.; Tagliazucchi, D. Effect of Ripening and in Vitro Digestion on the Evolution and Fate of Bioactive Peptides in Parmigiano-Reggiano Cheese. Int. Dairy. J. 2020, 105, 104668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, F.G.; Coitinho, L.B.; Dias, A.T.; Friques, A.G.F.; Monteiro, B.L.; de Rezende, L.C.D.; Pereira, T.d.M.C.; Campagnaro, B.P.; De Pauw, E.; Vasquez, E.C.; et al. Identification of New Bioactive Peptides from Kefir Milk through Proteopeptidomics: Bioprospection of Antihypertensive Molecules. Food Chem. 2019, 282, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.F.; Zhao, W.J.; Wu, R.N.; Sun, Z.H.; Zhang, W.Y.; Wang, J.C.; Bilige, M.; Zhang, H.P. Proteome Analysis of Lactobacillus helveticus H9 during Growth in Skim Milk. J. Dairy. Sci. 2014, 97, 7413–7425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, C.; Xue, J.; Kwok, L.; Yang, J.; Zhang, H.; Menghe, B. Characterization of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Activity of Fermented Milk Produced by Lactobacillus helveticus. J. Dairy. Sci. 2015, 98, 5113–5124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, D.P.; Galli, B.D.; Cavalheiro, F.G.; Negrão, F.; Eberlin, M.N.; Gigante, M.L. Lactobacillus helveticus LH-B02 Favours the Release of Bioactive Peptide during Prato Cheese Ripening. Int. Dairy. J. 2018, 87, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielecka, M.; Cichosz, G.; Czeczot, H. Antioxidant, Antimicrobial and Anticarcinogenic Activities of Bovine Milk Proteins and Their Hydrolysates—A Review. Int. Dairy. J. 2022, 127, 105208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenezini Chiozzi, R.; Capriotti, A.L.; Cavaliere, C.; La Barbera, G.; Piovesana, S.; Samperi, R.; Laganà, A. Purification and Identification of Endogenous Antioxidant and ACE-Inhibitory Peptides from Donkey Milk by Multidimensional Liquid Chromatography and NanoHPLC-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016, 408, 5657–5666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Salam, M.H.A.; El-Shibiny, S. Bioactive Peptides of Buffalo, Camel, Goat, Sheep, Mare, and Yak Milks and Milk Products. Food Rev. Int. 2013, 29, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, L.; Escudero, E.; Aristoy, M.-C.; Toldrá, F. A Peptidomic Approach to Study the Contribution of Added Casein Proteins to the Peptide Profile in Spanish Dry-Fermented Sausages. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 212, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejri, L.; Vásquez-Villanueva, R.; Hassouna, M.; Marina, M.L.; García, M.C. Identification of Peptides with Antioxidant and Antihypertensive Capacities by RP-HPLC-Q-TOF-MS in Dry Fermented Camel Sausages Inoculated with Different Starter Cultures and Ripening Times. Food Res. Int. 2017, 100, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, S.; Matsufuji, H.; Nakade, K.; Takenoyama, S.; Ahhmed, A.; Sakata, R.; Kawahara, S.; Muguruma, M. Investigation of Lactic Acid Bacterial Strains for Meat Fermentation and the Product’s Antioxidant and Angiotensin-I-converting-enzyme Inhibitory Activities. Anim. Sci. J. 2017, 88, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kononiuk, A.D.; Karwowska, M. Bioactive Compounds in Fermented Sausages Prepared from Beef and Fallow Deer Meat with Acid Whey Addition. Molecules 2020, 25, 2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, K.F.; Voo, A.Y.H.; Chen, W.N. Bioactive Peptides from Food Fermentation: A Comprehensive Review of Their Sources, Bioactivities, Applications, and Future Development. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 3825–3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriele, M.; Pucci, L. Fermentation and Germination as a Way to Improve Cereals Antioxidant and Antiinflammatory Properties. In Current Advances for Development of Functional Foods Modulating Inflammation and Oxidative Stress; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 477–497. [Google Scholar]

- Corpuz, H.M.; Fujii, H.; Nakamura, S.; Katayama, S. Fermented Rice Peptides Attenuate Scopolamine-Induced Memory Impairment in Mice by Regulating Neurotrophic Signaling Pathways in the Hippocampus. Brain Res. 2019, 1720, 146322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Rui, X.; Li, W.; Xiao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Dong, M. Whole-Grain Oats (Avena sativa L.) as a Carrier of Lactic Acid Bacteria and a Supplement Rich in Angiotensin I-Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Peptides through Solid-State Fermentation. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 2270–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyash, M.; Johnson, S.K.; Liu, S.-Q.; Mesmari, N.; Dahmani, S.; Al Dhaheri, A.S.; Kizhakkayil, J. In Vitro Investigation of Bioactivities of Solid-State Fermented Lupin, Quinoa and Wheat Using Lactobacillus spp. Food Chem. 2019, 275, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizzello, C.G.; Nionelli, L.; Coda, R.; Gobbetti, M. Synthesis of the Cancer Preventive Peptide Lunasin by Lactic Acid Bacteria During Sourdough Fermentation. Nutr. Cancer 2012, 64, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, C.-H.; Cho, S.-J. Improvement of Bioactivity of Soybean Meal by Solid-State Fermentation with Bacillus amyloliquefaciens versus Lactobacillus Spp. and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 68, 619–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Sun, M.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Miao, J.; Rui, X.; Dong, M. Effects of Cordyceps militaris (L.) Fr. Fermentation on the Nutritional, Physicochemical, Functional Properties and Angiotensin I Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Activity of Red Bean (Phaseolus angularis [Willd.] W.F. Wight.) Flour. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 1244–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihn, H.J.; Kim, J.A.; Lim, S.; Nam, S.-H.; Hwang, S.H.; Lim, J.; Kim, G.-Y.; Choi, Y.H.; Jeon, Y.-J.; Lee, B.-J.; et al. Fermented Oyster Extract Prevents Ovariectomy-Induced Bone Loss and Suppresses Osteoclastogenesis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.A.; Yao, Z.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, J.H. Properties of Gul Jeotgal (Oyster Jeotgal) Prepared with Different Types of Salt and Bacillus subtilis JS2 as Starter. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Lett. 2018, 46, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemil, I.; Abdelhedi, O.; Mora, L.; Nasri, R.; Aristoy, M.-C.; Jridi, M.; Hajji, M.; Toldrá, F.; Nasri, M. Peptidomic Analysis of Bioactive Peptides in Zebra Blenny (Salaria basilisca) Muscle Protein Hydrolysate Exhibiting Antimicrobial Activity Obtained by Fermentation with Bacillus Mojavensis A21. Process Biochem. 2016, 51, 2186–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafian, L.; Babji, A.S. Purification and Identification of Antioxidant Peptides from Fermented Fish Sauce (Budu). J. Aquat. Food Product. Technol. 2019, 28, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafian, L.; Babji, A.S. Fractionation and Identification of Novel Antioxidant Peptides from Fermented Fish (Pekasam). J. Food Meas. Charact. 2018, 12, 2174–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleekayai, T.; Harnedy, P.A.; O’Keeffe, M.B.; Poyarkov, A.A.; CunhaNeves, A.; Suntornsuk, W.; FitzGerald, R.J. Extraction of Antioxidant and ACE Inhibitory Peptides from Thai Traditional Fermented Shrimp Pastes. Food Chem. 2015, 176, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Mata, D.I.; Salinas-Carmona, M.C. Antimicrobial Peptides’ Immune Modulation Role in Intracellular Bacterial Infection. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1119574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.-Y.; Yan, Z.-B.; Meng, Y.-M.; Hong, X.-Y.; Shao, G.; Ma, J.-J.; Cheng, X.-R.; Liu, J.; Kang, J.; Fu, C.-Y. Antimicrobial Peptides: Mechanism of Action, Activity and Clinical Potential. Mil. Med. Res. 2021, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, J.-P.S.; Hancock, R.E.W. The Relationship between Peptide Structure and Antibacterial Activity. Peptides 2003, 24, 1681–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciulla, M.G.; Gelain, F. Structure–Activity Relationships of Antibacterial Peptides. Microb. Biotechnol. 2023, 16, 757–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echegaray, N.; Yilmaz, B.; Sharma, H.; Kumar, M.; Pateiro, M.; Ozogul, F.; Lorenzo, J.M. A Novel Approach to Lactiplantibacillus plantarum: From Probiotic Properties to the Omics Insights. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 268, 127289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, B.; Bangar, S.P.; Echegaray, N.; Suri, S.; Tomasevic, I.; Manuel Lorenzo, J.; Melekoglu, E.; Rocha, J.M.; Ozogul, F. The Impacts of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum on the Functional Properties of Fermented Foods: A Review of Current Knowledge. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algboory, H.L.; Muhialdin, B.J. Novel Peptides Contribute to the Antimicrobial Activity of Camel Milk Fermented with Lactobacillus plantarum IS10. Food Control 2021, 126, 108057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Qian, Y.; Gao, Q.; Yan, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Luo, X.; Shen, J.; Liu, Y. Discovery, Characterization, and Application of a Novel Antimicrobial Peptide Produced by Lactiplantibacillus plantarum FB-2. Food Biosci. 2024, 58, 103663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulrajah, B.; Qoms, M.S.; Muhialdin, B.J.; Hasan, H.; Zarei, M.; Meor Hussin, A.S.; Chau, D.-M.; Saari, N. Antibacterial and Antifungal Activity of Kenaf Seed Peptides and Their Effect on Microbiological Safety and Physicochemical Properties of Some Food Models. Food Control 2022, 140, 109119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Yu, J.; Shao, S. Advances in the Application and Mechanism of Bioactive Peptides in the Treatment of Inflammation. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1413179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, E.C.; Heran, B.S.; Wright, J.M. Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitors versus Angiotensin Receptor Blockers for Primary Hypertension. In Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; Li, E.C., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Balti, R.; Bougatef, A.; Sila, A.; Guillochon, D.; Dhulster, P.; Nedjar-Arroume, N. Nine Novel Angiotensin I-Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitory Peptides from Cuttlefish (Sepia officinalis) Muscle Protein Hydrolysates and Antihypertensive Effect of the Potent Active Peptide in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Food Chem. 2015, 170, 519–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majumder, K.; Chakrabarti, S.; Morton, J.S.; Panahi, S.; Kaufman, S.; Davidge, S.T.; Wu, J. Egg-Derived ACE-Inhibitory Peptides IQW and LKP Reduce Blood Pressure in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 13, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskaya-Dikmen, C.; Yucetepe, A.; Karbancioglu-Guler, F.; Daskaya, H.; Ozcelik, B. Angiotensin-I-Converting Enzyme (ACE)-Inhibitory Peptides from Plants. Nutrients 2017, 9, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Zhang, Q.; Ji, Z.; Shu, G.; Chen, H. Production and Fermentation Characteristics of Angiotensin-I-Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Peptides of Goat Milk Fermented by a Novel Wild Lactobacillus plantarum 69. LWT 2018, 91, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Xu, W.; Liu, K.; Xia, Y. Shuangquan Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Peptides from Lactobacillus delbrueckii QS306 Fermented Milk. J. Dairy. Sci. 2019, 102, 5913–5921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, M.; Mora, L.; Escudero, E.; Toldrá, F. Bioactive Peptides and Free Amino Acids Profiles in Different Types of European Dry-Fermented Sausages. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 276, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubczyk, A.; Karaś, M.; Złotek, U.; Szymanowska, U.; Baraniak, B.; Bochnak, J. Peptides Obtained from Fermented Faba Bean Seeds (Vicia faba) as Potential Inhibitors of an Enzyme Involved in the Pathogenesis of Metabolic Syndrome. LWT 2019, 105, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Aluko, R.E.; Nakai, S. Structural Requirements of Angiotensin I-Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Peptides: Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship Modeling of Peptides Containing 4-10 Amino Acid Residues. QSAR Comb. Sci. 2006, 25, 873–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Aluko, R.E.; Nakai, S. Structural Requirements of Angiotensin I-Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Peptides: Quantitative Structure−Activity Relationship Study of Di- and Tripeptides. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 732–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, B.J.; Mugesh, G. Antioxidant Activity of Peptide-Based Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.R.; Burney, J.D.; Black, K.W.; Zaloga, G.P. Effect of Chain Length on Absorption of Biologically Active Peptides from the Gastrointestinal Tract. Digestion 1999, 60, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, W.; Matsui, T. Intestinal Absorption of Small Peptides: A Review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 1942–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirdhayati, I.; Zain, W.N.H.; Fatah, A.; Yokoyama, I.; Arihara, K. Purification of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Peptides and Antihypertensive Effect Generated from Indonesian Traditional Fermented Beef (Cangkuk). Anim. Biosci. 2024, 37, 1799–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyazaki, H.; Nakamura, T.; Ohki, K.; Nagai, K. Effects of the Bioactive Peptides Ile-Pro-Pro and Val-Pro-Pro upon Autonomic Neurotransmission and Blood Pressure in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Auton. Neurosci. 2017, 208, 88–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicero, A.F.G.; Colletti, A.; Rosticci, M.; Cagnati, M.; Urso, R.; Giovannini, M.; Borghi, C.; D’Addato, S. Effect of Lactotripeptides (Isoleucine–Proline–Proline/Valine–Proline–Proline) on Blood Pressure and Arterial Stiffness Changes in Subjects with Suboptimal Blood Pressure Control and Metabolic Syndrome: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Crossover Clinical Trial. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2016, 14, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moayedi, A.; Mora, L.; Aristoy, M.C.; Safari, M.; Hashemi, M.; Toldrá, F. Peptidomic Analysis of Antioxidant and ACE-Inhibitory Peptides Obtained from Tomato Waste Proteins Fermented Using Bacillus subtilis. Food Chem. 2018, 250, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theansungnoen, T.; Yaraksa, N.; Daduang, S.; Dhiravisit, A.; Thammasirirak, S. Purification and Characterization of Antioxidant Peptides from Leukocyte Extract of Crocodylus siamensis. Protein J. 2014, 33, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchalska, P.; Marina, M.L.; García, M.C. Isolation and Identification of Antioxidant Peptides from Commercial Soybean-Based Infant Formulas. Food Chem. 2014, 148, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspar-Pintiliescu, A.; Oancea, A.; Cotarlet, M.; Vasile, A.M.; Bahrim, G.E.; Shaposhnikov, S.; Craciunescu, O.; Oprita, E.I. Angiotensin-converting Enzyme Inhibition, Antioxidant Activity and Cytotoxicity of Bioactive Peptides from Fermented Bovine Colostrum. Int. J. Dairy. Technol. 2020, 73, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, T.-B.; He, T.-P.; Li, H.-B.; Tang, H.-W.; Xia, E.-Q. The Structure-Activity Relationship of the Antioxidant Peptides from Natural Proteins. Molecules 2016, 21, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W. Evaluation of the Antioxidant Activity and Identification of Potential Antioxidant Peptides in Commercially Available Probiotic Cheddar Cheese. LWT 2024, 205, 116486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, S.; Kumar, N.; Kapila, S.; Mada, S.B.; Reddi, S.; Vij, R.; Kapila, R. Buffalo Casein Derived Peptide Can Alleviates H2O2 Induced Cellular Damage and Necrosis in Fibroblast Cells. Exp. Toxicol. Pathol. 2017, 69, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, M.-Y.; Dong, G.; Yang, B.-Q.; Feng, H. Identification and Characterization of a Novel Antioxidant Peptide from Feather Keratin Hydrolysate. Biotechnol. Lett. 2016, 38, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Zhao, J.; Xie, Y.; Tang, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Xu, M.; Liu, P. Identification and Molecular Mechanisms of Novel Antioxidant Peptides from Fermented Broad Bean Paste: A Combined in Silico and in Vitro Study. Food Chem. 2024, 450, 139297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Cui, L.; Tu, X.; Liang, Y.; Wang, L.; Sun, Y.; Kang, X.; Wu, Z. Peptides Derived from Casein Hydrolyzed by Lactobacillus: Screening and Antioxidant Properties in H2O2-Induced HepG2 Cells Model. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 117, 106221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Fan, L.; Ding, L.; Yang, W.; Zang, C.; Guan, H. Separation and Purification of Antioxidant Peptide from Fermented Whey Protein by Lactobacillus rhamnosus B2-1. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2023, 43, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlicevic, M.; Marmiroli, N.; Maestri, E. Immunomodulatory Peptides—A Promising Source for Novel Functional Food Production and Drug Discovery. Peptides 2022, 148, 170696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Habermann, D.; Kliche, T.; Klempt, M.; Wutkowski, A.; Clawin-Rädecker, I.; Koberg, S.; Brinks, E.; Koudelka, T.; Tholey, A.; et al. Soluble Lactobacillus delbrueckii Subsp. Bulgaricus 92059 PrtB Proteinase Derivatives for Production of Bioactive Peptide Hydrolysates from Casein. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 2731–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Fu, L.; Hao, Y.; Miao, Y.; Zhang, W. Xuanwei Ham Derived Peptides Exert the Anti-Inflammatory Effect in the Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Induced C57BL/6 Mice Model. Food Biosci. 2022, 48, 101800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Bi, H.; Zhou, X.; Jiang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Fu, X.; Yang, B. Structure Characterization of Soybean Peptides and Their Protective Activity against Intestinal Inflammation. Food Chem. 2022, 387, 132868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, H.J.; Schibli, D.J.; Jing, W.; Lohmeier-Vogel, E.M.; Epand, R.F.; Epand, R.M. Towards a Structure-Function Analysis of Bovine Lactoferricin and Related Tryptophan- and Arginine-Containing Peptides. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2002, 80, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guha, S.; Majumder, K. Structural-Features of Food-Derived Bioactive Peptides with Anti-Inflammatory Activity: A Brief Review. J. Food Biochem. 2019, 43, e12531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gao, X.; Pan, D.; Liu, Z.; Xiao, C.; Xiong, Y.; Du, L.; Cai, Z.; Lu, W.; Dang, Y.; et al. Identification and Virtual Screening of Novel Anti-Inflammatory Peptides from Broccoli Fermented by Lactobacillus strains. Front. Nutr. 2023, 9, 1118900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Yamamoto, N.; Sakai, K.; Okubo, A.; Yamazaki, S.; Takano, T. Purification and Characterization of Angiotensin I-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors from Sour Milk. J. Dairy. Sci. 1995, 78, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, U.; Nataraj, B.H.; Kumari, M.; Kadyan, S.; Puniya, A.K.; Behare, P.V.; Nagpal, R. Antioxidant and Immunomodulatory Potency of Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus NCDC24 Fermented Milk-Derived Peptides: A Computationally Guided in-Vitro and Ex-Vivo Investigation. Peptides 2022, 155, 170843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.; Gotou, T.; Kitajima, H.; Mizuno, S.; Nakazawa, T.; Yamamoto, N. Release of Antihypertensive Peptides in Miso Paste during Its Fermentation, by the Addition of Casein. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2009, 108, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Gonzalez, C.; Gibson, T.; Jauregi, P. Novel Probiotic-Fermented Milk with Angiotensin I-Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Peptides Produced by Bifidobacterium Bifidum MF 20/5. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 167, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhialdin, B.J.; Abdul Rani, N.F.; Meor Hussin, A.S. Identification of Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities for the Bioactive Peptides Generated from Bitter Beans (Parkia speciosa) via Boiling and Fermentation Processes. LWT 2020, 131, 109776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirós, A.; Ramos, M.; Muguerza, B.; Delgado, M.A.; Miguel, M.; Aleixandre, A.; Recio, I. Identification of Novel Antihypertensive Peptides in Milk Fermented with Enterococcus faecalis. Int. Dairy. J. 2007, 17, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulrajah, B.; Muhialdin, B.J.; Zarei, M.; Hasan, H.; Saari, N. Lacto-Fermented Kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.) Seed Protein as a Source of Bioactive Peptides and Their Applications as Natural Preservatives. Food Control 2020, 110, 106969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjukta, S.; Rai, A.K.; Muhammed, A.; Jeyaram, K.; Talukdar, N.C. Enhancement of Antioxidant Properties of Two Soybean Varieties of Sikkim Himalayan Region by Proteolytic Bacillus subtilis Fermentation. J. Funct. Foods 2015, 14, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purohit, K.; Reddy, N.; Sunna, A. Exploring the Potential of Bioactive Peptides: From Natural Sources to Therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Augustin, O.; Rivero-Gutiérrez, B.; Mascaraque, C.; Sánchez de Medina, F. Food Derived Bioactive Peptides and Intestinal Barrier Function. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 22857–22873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, M.; Tiwari, B. Bioactive Carbohydrates and Peptides in Foods: An Overview of Sources, Downstream Processing Steps and Associated Bioactivities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 22485–22508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, H.; Tao, X.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Y.; Yu, Q.; Xie, J. Food-Derived Bioactive Peptides: Production, Biological Activities, Opportunities and Challenges. J. Future Foods 2022, 2, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtaza, M.A.; Irfan, S.; Hafiz, I.; Ranjha, M.M.A.N.; Rahaman, A.; Murtaza, M.S.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Siddiqui, S.A. Conventional and Novel Technologies in the Production of Dairy Bioactive Peptides. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 780151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, M.; Nadeem, M.; Mahmood Qureshi, T.; Gamlath, C.J.; Martin, G.J.O.; Hemar, Y.; Ashokkumar, M. Effect of Sonication, Microwaves and High-Pressure Processing on ACE-Inhibitory Activity and Antioxidant Potential of Cheddar Cheese during Ripening. Ultrason. Sonochem 2020, 67, 105140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Ma, Y.; An, F.; Yu, M.; Zhang, L.; Tao, X.; Pan, G.; Liu, Q.; Wu, J.; Wu, R. Ultrasound-Assisted Fermentation for Antioxidant Peptides Preparation from Okara: Optimization, Stability, and Functional Analyses. Food Chem. 2024, 439, 138078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Zhang, F.; Shuang, Q. Peptidomic Analysis of the Angiotensin-Converting-Enzyme Inhibitory Peptides in Milk Fermented with Lactobacillus delbrueckii QS306 after Ultrahigh Pressure Treatment. Food Res. Int. 2023, 164, 112406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khakhariya, R.; Basaiawmoit, B.; Sakure, A.A.; Maurya, R.; Bishnoi, M.; Kondepudi, K.K.; Padhi, S.; Rai, A.K.; Liu, Z.; Hati, S. Production and Characterization of ACE Inhibitory and Anti-Diabetic Peptides from Buffalo and Camel Milk Fermented with Lactobacillus and Yeast: A Comparative Analysis with in Vitro, In Silico, and Molecular Interaction Study. Foods 2023, 12, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Sharma, D.; Kaur, S.; Borah, A. Optimization of Flaxseed Milk Fermentation for the Production of Functional Peptides and Estimation of Their Bioactivities. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2021, 27, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bautista-Expósito, S.; Peñas, E.; Silván, J.M.; Frias, J.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C. PH-Controlled Fermentation in Mild Alkaline Conditions Enhances Bioactive Compounds and Functional Features of Lentil to Ameliorate Metabolic Disturbances. Food Chem. 2018, 248, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbarbaglu, Z.; Ayaseh, A.; Ghanbarzadeh, B.; Sarabandi, K. Biological Stabilization of Arthrospira Bioactive-Peptides within Biopolymers: Functional Food Formulation; Bitterness-Masking and Nutritional Aspects. LWT 2024, 191, 115653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdo, A.A.A.; Al-Dalali, S.; Hou, Y.; Aleryani, H.; Shehzad, Q.; Asawmahi, O.; AL-Farga, A.; Mohammed, B.; Liu, X.; Sang, Y. Modification of Marine Bioactive Peptides: Strategy to Improve the Biological Activity, Stability, and Taste Properties. Food Bioproc Tech. 2024, 17, 1412–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atma, Y.; Murray, B.S.; Sadeghpour, A.; Goycoolea, F.M. Encapsulation of Short-Chain Bioactive Peptides (BAPs) for Gastrointestinal Delivery: A Review. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 3959–3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pérez, V.; Jiménez-Martínez, C.; González-Escobar, J.L.; Corzo-Ríos, L.J. Exploring the Impact of Encapsulation on the Stability and Bioactivity of Peptides Extracted from Botanical Sources: Trends and Opportunities. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1423500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekshmi, R.G.K.; Tejpal, C.S.; Anas, K.K.; Chatterjee, N.S.; Mathew, S.; Ravishankar, C.N. Binary Blend of Maltodextrin and Whey Protein Outperforms Gum Arabic as Superior Wall Material for Squalene Encapsulation. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 121, 106976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarabandi, K.; Karami, Z.; Akbarbaglu, Z.; Duangmal, K.; Jafari, S.M. Spray-Drying Stabilization of Oleaster-Seed Bioactive Peptides within Biopolymers: Pan-Bread Formulation and Bitterness-Masking. Food Biosci. 2024, 58, 103837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ju, X.; He, R.; Yuan, J.; Wang, L. The Effect of Rapeseed Protein Structural Modification on Microstructural Properties of Peptide Microcapsules. Food Bioproc. Tech. 2015, 8, 1305–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongcumsuk, B.; Woraprayote, W.; Janyaphisan, T.; Cheunkar, S.; Oaew, S. Microencapsulation and Peptide Identification of Purified Bioactive Fraction from Spirulina Protein Hydrolysates with Dipeptidyl Peptidase IV (DPP-IV) Inhibitory Activity. Food Biosci. 2023, 56, 103438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharehbeglou, P.; Homayouni-Rad, A.; Jafari, S.M.; Sarabandi, K.; Akbarbaglu, Z. Stabilization of Chlorella Bioactive Hydrolysates Within Biopolymeric Carriers: Techno-Functional, Structural, and Biological Properties. J. Polym. Environ. 2024, 32, 763–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, N.; Sarmah, M.; Khatun, B.; Maji, T.K. Encapsulation of Active Ingredients in Polysaccharide–Protein Complex Coacervates. Adv. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2017, 239, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thapa, R.K.; Kim, J.O. Nanomedicine-Based Commercial Formulations: Current Developments and Future Prospects. J. Pharm. Investig. 2023, 53, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javadi, B.; Farahmand, A.; Soltani-Gorde-Faramarzi, S.; Hesarinejad, M.A. Chitosan-Coated Nanoliposome: An Approach for Simultaneous Encapsulation of Caffeine and Roselle-Anthocyanin in Beverages. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 275, 133469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazloomi, S.N.; Mahoonak, A.S.; Ghorbani, M.; Houshmand, G. Physicochemical Properties of Chitosan-Coated Nanoliposome Loaded with Orange Seed Protein Hydrolysate. J. Food Eng. 2020, 280, 109976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalatbari, S.; Hasani, M.; Khoshvaght-Aliabadi, M. Investigating the Characteristics of Nanoliposomes Carrying Bioactive Peptides Obtained from Shrimp Waste. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2024, 30, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pateiro, M.; Gómez, B.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Barba, F.J.; Putnik, P.; Kovačević, D.B.; Lorenzo, J.M. Nanoencapsulation of Promising Bioactive Compounds to Improve Their Absorption, Stability, Functionality and the Appearance of the Final Food Products. Molecules 2021, 26, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intiquilla, A.; Jiménez-Aliaga, K.; Iris Zavaleta, A.; Gamboa, A.; Caro, N.; Diaz, M.; Gotteland, M.; Abugoch, L.; Tapia, C. Nanoencapsulation of Antioxidant Peptides from Lupinus mutabilis in Chitosan Nanoparticles Obtained by Ionic Gelling and Spray Freeze Drying Intended for Colonic Delivery. Food Biosci. 2022, 50, 102055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Fang, F.; Wang, S. Physicochemical Properties and Hepatoprotective Effects of Glycated Snapper Fish Scale Peptides Conjugated with Xylose via Maillard Reaction. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 137, 111115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peres Fabbri, L.; Cavallero, A.; Vidotto, F.; Gabriele, M. Bioactive Peptides from Fermented Foods: Production Approaches, Sources, and Potential Health Benefits. Foods 2024, 13, 3369. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13213369

Peres Fabbri L, Cavallero A, Vidotto F, Gabriele M. Bioactive Peptides from Fermented Foods: Production Approaches, Sources, and Potential Health Benefits. Foods. 2024; 13(21):3369. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13213369

Chicago/Turabian StylePeres Fabbri, Laryssa, Andrea Cavallero, Francesca Vidotto, and Morena Gabriele. 2024. "Bioactive Peptides from Fermented Foods: Production Approaches, Sources, and Potential Health Benefits" Foods 13, no. 21: 3369. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13213369

APA StylePeres Fabbri, L., Cavallero, A., Vidotto, F., & Gabriele, M. (2024). Bioactive Peptides from Fermented Foods: Production Approaches, Sources, and Potential Health Benefits. Foods, 13(21), 3369. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13213369