In Silico Screening of Bioactive Peptides in Stout Beer and Analysis of ACE Inhibitory Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.3. Isolation and Identification of Peptides

2.4. Screening of Bioactive Peptides In Silico

2.5. Toxicity and Solubility Prediction

2.6. Absorption and Excretion Properties Analysis

2.7. Molecular Docking

2.7.1. Preparation of Small Molecules

2.7.2. Preparation of Protein Structure

2.7.3. Molecular Docking

2.7.4. 2D Structure Visualization

2.8. MD Simulation

2.9. Determination of ACEI Activity In Vitro

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Identification of Peptides

3.2. Process of Selecting Stout Beer Peptides

3.2.1. Activity Score and Prediction

3.2.2. Evaluation of the Properties of the Selected Peptides

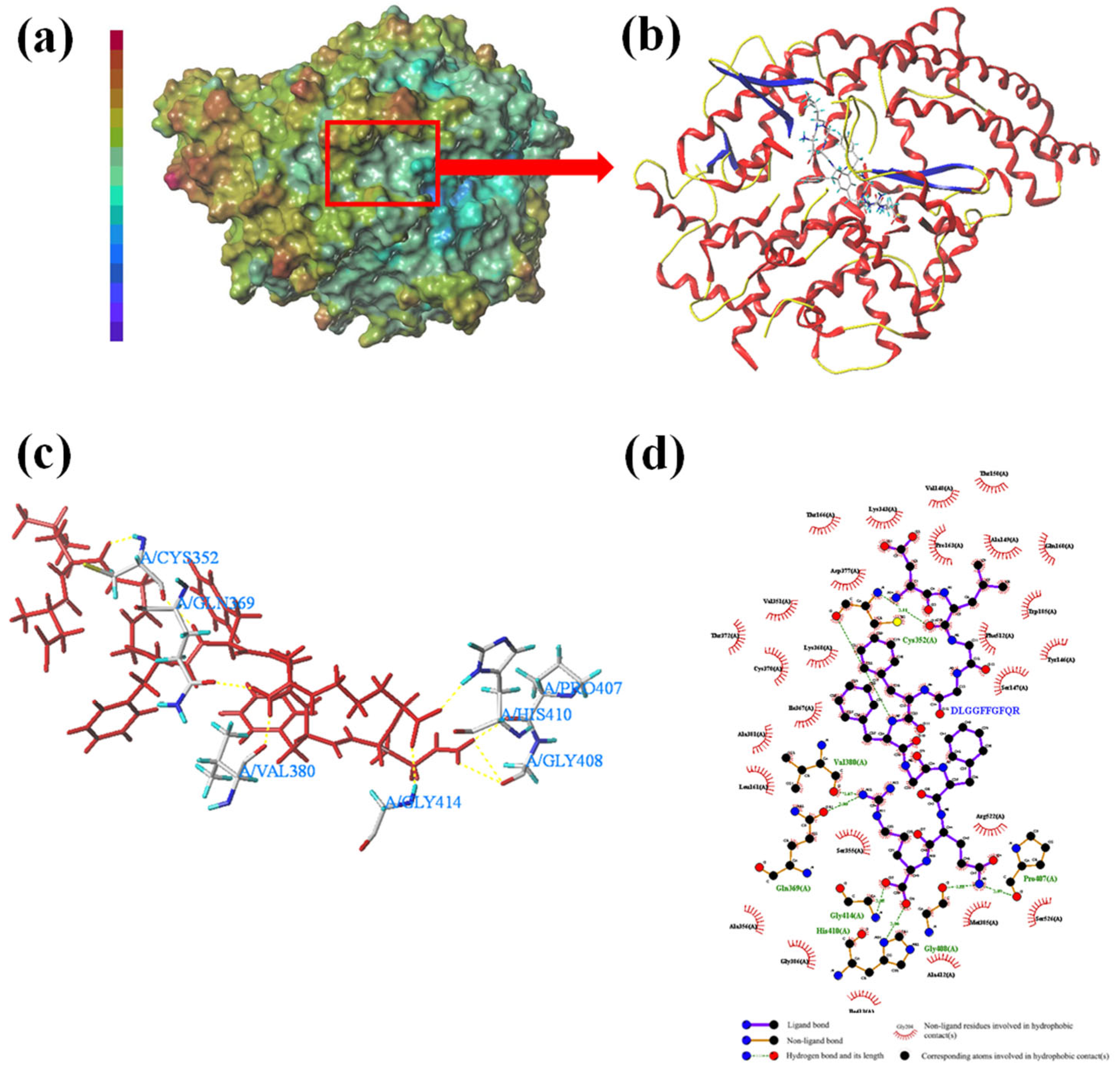

3.3. Molecular Docking

3.4. Molecular Docking Conformation Analysis

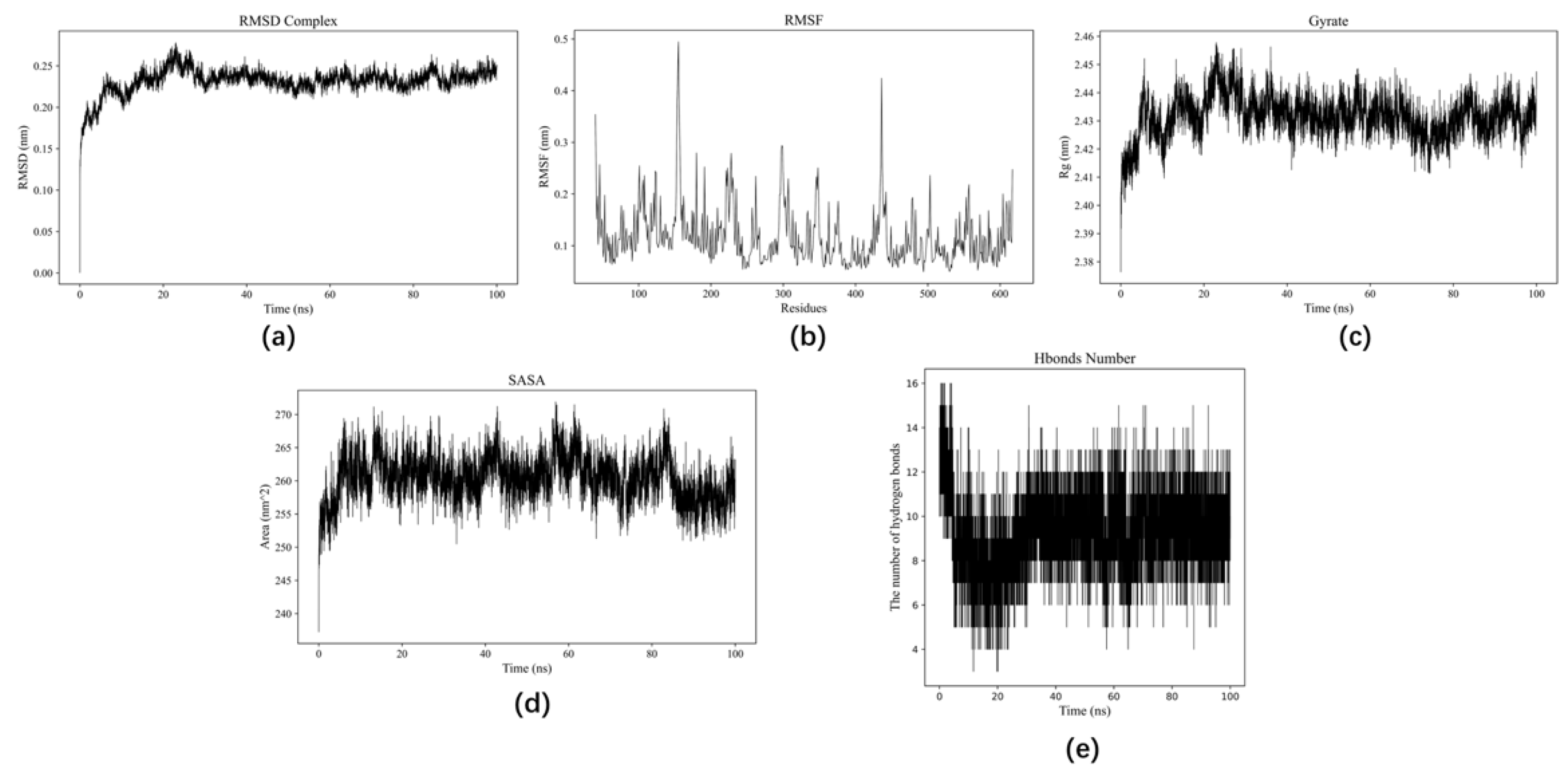

3.5. MD Simulation Analysis

3.6. In Vitro Analysis of ACEI Activity

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mills, K.T.; Stefanescu, A.; He, J. The global epidemiology of hypertension. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2020, 16, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, R.; Yin, L.; Li, L.; Silva-Nash, J.; Yan, L. Hypertension in China: Burdens, guidelines and policy responses: A state-of-the-art review. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2022, 36, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kario, K.; Okura, A.; Hoshide, S.; Mogi, M. The WHO Global report 2023 on hypertension warning the emerging hypertension burden in globe and its treatment strategy. Hypertens. Res. 2024, 47, 1099–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, J.; Miyakawa, T.; Li, G.; Gu, R.; Tanokura, M. Antioxidant properties and inhibition of angiotensin-converting enzyme by highly active peptides from wheat gluten. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngoh, Y.-Y.; Gan, C.-Y. Identification of Pinto bean peptides with inhibitory effects on α-amylase and angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) activities using an integrated bioinformatics-assisted approach. Food Chem. 2018, 267, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, R.; Meisel, H. Food-derived peptides with biological activity: From research to food applications. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2007, 18, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, P.; Chopada, K.; Sakure, A.; Hati, S. Current Trends and Applications of Food-derived Antihypertensive Peptides for the Management of Cardiovascular Disease. Protein Pept. Lett. 2022, 29, 408–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganguly, A.; Sharma, K.; Majumder, K. Food-derived bioactive peptides and their role in ameliorating hypertension and associated cardiovascular diseases. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2019, 89, 165–207. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Loas, A.; Pentelute, B.L. Introduction: Peptide Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 3049–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, N.M.; Bandyopadhyay, A. High throughput virtual screening (HTVS) of peptide library: Technological advancement in ligand discovery. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 243, 114766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Sun, B.; Zhao, M.; Zheng, F.; Sun, J.; Sun, X.; Li, H.; Huang, M. Discovery of a Bioactive Peptide, an Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor in Chinese Baijiu. J. Chin. Inst. Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 16, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Lu, A.; Sun, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Huang, P.; Yang, A.; Li, Z.; Cao, Y.; et al. Purification and identification of antioxidant and angiotensin converting enzyme-inhibitory peptides from Guangdong glutinous rice wine. LWT 2022, 169, 113953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Yan, R.; Jiang, Y.; Feng, S.; Sun, H.; Sun, J.; Zhao, D.; Li, H.; Wang, B.; Zhang, N. Identification of peptides in Qingke baijiu and evaluation of its angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory activity and stability. Food Chem. 2022, 395, 133551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinojosa-Avila, C.R.; García-Gamboa, R.; Chedraui-Urrea, J.J.T.; García-Cayuela, T. Exploring the potential of probiotic-enriched beer: Microorganisms, fermentation strategies, sensory attributes, and health implications. Food Res. Int. 2024, 175, 113717. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, W.; Baumert, J.L.; Downs, M.L. Compositional and immunogenic evaluation of fractionated wheat beers using mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 2020, 333, 127379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zugravu, C.-A.; Medar, C.; Manolescu, L.S.C.; Constantin, C. Beer and Microbiota: Pathways for a Positive and Healthy Interaction. Nutrients 2023, 15, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Q.; Sun, J.; Wang, B.; Sun, B. Wine, beer and Chinese Baijiu in relation to cardiovascular health: The impact of moderate drinking. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2023, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaetano, G.; Costanzo, S.; Castelnuovo, A.D.; Badimon, L.; Bejko, D.; Alkerwi, A.; Chiva-Blanch, G.; Estruch, R.; Vecchia, C.L.; Panico, S.; et al. Effects of moderate beer consumption on health and disease: A consensus document. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2016, 26, 443–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lordan, R.; Keeffe, E.; Dowling, D.; Mullally, M.; Heffernan, H.; Tsoupras, A.; Zabetakis, I. The in vitro antithrombotic properties of ale, lager, and stout beers. Food Biosci. 2019, 28, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, H.G.; Decloedt, A.I.; Hemetyck, L.Y.; Landschoot, A.V.; Prenni, J. Peptidomics of an industrial gluten-free barley malt beer and its non-gluten-free counterpart: Characterisation and immunogenicity. Food Chem. 2021, 355, 129597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodolo, E.J.; Kock, J.L.F.; Axcell, B.C.; Brooks, M. The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae-the main character in beer brewing. FEMS Yeast Res. 2008, 8, 1018–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merinas-Amo, T.; Martinez-Jurado, M.; Merinas-Amo, R.; Mateo-Fenandez, M.M.; Alonso-Moraga, A. In vivo and in vitro toxicological and biological activities of alpha-acid humulone, isoxanthohumol and stout beer. Toxicol. Lett. 2014, 229, 179–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jiang, W.; Zhao, S.; Wang, D.; Tang, K. Analysis of 15 kinds of malt aroma characteristic substances in malt and stout. Food Ferment. Ind. 2014, 8, 171–177. [Google Scholar]

- Liguori, L.; Francesco, G.D.; Orilio, P.; Perretti, G.; Albanese, D. Influence of malt composition on the quality of a top fermented beer. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 58, 2295–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negrão, R.; Costa, R.; Duarte, D.; Taveira-Gomes, T.; Mendanha, M.; Soares, R. Angiogenic and Inflammatory activities are modulated in vivo by polyphenol supplemented beer. FASEB J. 2010, 24, 535.5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, J.; Sun, B.; Zheng, F.; Sun, J.; Sun, X.; Li, H.; Luo, X.; Huang, M. Identification of a Tripeptide Arg-Asn-His from Chinese Baijiu and Its Antioxidant Activity. Food Sci. 2018, 23, 126–133. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Zhuang, Y.; Sun, L. Identification and characterization of the peptides with calcium-binding capacity from tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) skin gelatin enzymatic hydrolysates. Food Chem. 2020, 85, 114–122. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Zhang, F.; Guo, S.; Shen, Q. Comparison of the generation of α-glucosidase inhibitory peptides derived from prolamins of raw and cooked foxtail millet: In vitro activity, de novo sequencing, and in silico docking. Food Chem. 2023, 411, 135378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uriel, U.-R.; Liceaga, A.M.; Reddivari, L.; Kim, K.-H.; Anderson, J.M. Enzyme kinetics, molecular docking, and in silico characterization of canary seed (Phalaris canariensis L.) peptides with ACE and pancreatic lipase inhibitory activity. J. Funct. Foods 2022, 88, 104892. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, I.; Mashwani, Z.-R.; Younas, Z.; Yousaf, T.; Ahmad, A.; Vladulescu, C. Antioxidant activity, metabolic profiling, in-silico molecular docking and ADMET analysis of nano selenium treated sesame seed bioactive compounds as potential novel drug targets against cardiovascular disease related receptors. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Chang, W.; Ma, Q.; Zhuang, Y. Purification of Antioxidant Peptides by High Resolution Mass Spectrometry from Simulated Gastrointestinal Digestion Hydrolysates of Alaska Pollock (Theragra chalcogramma) Skin Collagen. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Y.; Ma, Q.; Guo, Y.; Sun, L. Protective effects of rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum) peel phenolics on H2O2-induced oxidative damages in HepG2 cells and D-galactose-induced aging mice. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 108, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoel, D.V.D.; Lindahl, E.; Hess, B.; Groenhof, G.; Mark, A.E.; Berendsen, H.J.C. GROMACS: Fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem. 2005, 26, 1701–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahmani, M.; Juhász, A.; Bose, U.; Nye-Wood, M.G.; Blundell, M.; Howitt, C.A.; Colgrave, M.L. From grain to malt: Tracking changes of ultra-low-gluten barley storage proteins after malting. Food Chem. 2024, 432, 137189. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Picariello, G.; Bonomi, F.; Iametti, S.; Rasmussen, P.; Pepe, C.; Lilla, S.; Ferranti, P. Proteomic and peptidomic characterisation of beer: Immunological and technological implications. Food Chem. 2011, 124, 1718–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picariello, G.; Mamone, G.; Nitride, C.; Addeo, F.; Camarca, A.; Vocca, I.; Gianfrani, C.; Ferranti, P. Shotgun proteome analysis of beer and the immunogenic potential of beer polypeptides. J. Proteom. 2012, 75, 5872–5882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Hu, S.; Zhuang, Y.; Sun, L.; Yin, H. Identification of angiotensin-converting enzyme and dipeptidyl peptidase inhibitory peptides from draft beer by virtual screening and molecular docking. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022, 102, 1085–1094. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Huang, J.; Hu, J.; Yan, R.; Ma, X. Comparative study on the phytochemical profiles and cellular antioxidant activity of phenolics extracted from barley malts processed under different roasting temperatures. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 2176–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Sun, L.; Zhang, C.; Hu, S.; Zhuang, Y.; Yin, H. Virtual Screening of Activity Evaluation of Dipeptidyl Peptidase-IV Inhibitory Peptides in White Beer. Food Sci. 2022, 10, 81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F.; Chen, X.; Huang, M.; Yang, Q.; Cai, X.; Chen, X.; Du, M.; Huang, J.; Wang, S. Molecular characteristics and structure–activity relationships of food-derived bioactive peptides. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 2313–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhou, X.; Sun, L.; Zhuang, Y. Identification, in silico screening, and molecular docking of novel ACE inhibitory peptides isolated from the edible symbiot Boletus griseus-Hypomyces chrysospermus. LWT 2022, 169, 114008. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, M.; Feng, Y.; Miao, Y.; Shen, Q.; Tang, S.; Dong, J.; Zhang, J.Z.H.; Zhang, L. Revealing the Sequence Characteristics and Molecular Mechanisms of ACE Inhibitory Peptides by Comprehensive Characterization of 160,000 Tetrapeptides. Foods 2023, 12, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Niguram, P.; Bhat, V.; Jinagal, S.; Jairaj, V.; Chauhan, N. Synthesis, molecular docking and ADMET prediction of novel swertiamarin analogues for the restoration of type-2 diabetes: An enzyme inhibition assay. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 36, 2197–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, W.; Ding, L.; Zheng, F.; Li, J.; Liu, J. Identification and molecular mechanism of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides from Larimichthys crocea titin. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2020, 9, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobe, A.; Antony, P.; Altabbal, S.; Dhaheri, Y.A.; Vijayan, R. Interaction of hemorphins with ACE homologs. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bare, Y.; Kuki, A.; Tiring, S.S.N.D.; Rophi, A.H.; Krisnamurti, G.C.; Sari, D.R.T. In Silico Study: Prediction the Potential of Caffeic Acid As ACE inhibitor. El-Hayah J. Biol. 2019, 7, 94–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, W.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, D.; Yan, M.; Ma, H.; Yang, Y. Structure–Activity Relationship of Novel ACE Inhibitory Undecapeptides from Stropharia rugosoannulata by Molecular Interactions and Activity Analyses. Foods 2023, 12, 3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Y.; Yan, W.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, Z. A novel angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory peptide from tilapia skin: Preparation, identification and its potential antihypertensive mechanism. Food Chem. 2024, 430, 137074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Pan, D.; Yang, Z.; Gao, X.; Dang, Y. Angiotensin I-Converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory and dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 (DPP-Ⅳ) inhibitory activity of umami peptides from Ruditapes philippinarum. LWT 2021, 144, 111265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, M.; Ghanbari, R.; Zainal, N.; Ovissipour, R.; Saari, N. Inhibition kinetics, molecular docking, and stability studies of the effect of papain-generated peptides from palm kernel cake proteins on angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE). Food Chem. Mol. Sci. 2022, 5, 100147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutopo, C.C.Y.; Aznam, N.; Arianingrum, R.; Hsu, J.-L. Screening potential hypertensive peptides using two consecutive bioassay-guided SPE fractionations and identification of an ACE inhibitory peptide, DHSTAVW (DW7), derived from pearl garlic protein hydrolysate. Peptides 2023, 167, 171046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No | Peptide | RT | Tag Length | ALC (%) | Mass | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ALDTRVGV | 15.67 | 8 | 94 | 829.4658 | |

| 2 | LPQQQAQFK | 13.86 | 9 | 93 | 1086.5823 | Tian et al. [41] |

| 3 | STEWHLD | 17.12 | 7 | 93 | 886.3821 | Tian et al. [41] |

| 4 | TDVRLS | 10.05 | 6 | 93 | 689.3708 | |

| 5 | MFALPVPSQPVD | 18.84 | 12 | 91 | 1299.6533 | |

| 6 | VAVAREVAVG | 14.41 | 10 | 91 | 969.5607 | |

| 7 | FDRLQ | 11.86 | 5 | 91 | 677.3497 | |

| 8 | PPPVHD | 4.48 | 6 | 91 | 660.3231 | Tian et al. [41] |

| 9 | LASQLGLGGLSSL | 19.07 | 13 | 90 | 1214.6870 | |

| 10 | QAAVGGQVVEK | 12.17 | 11 | 90 | 1084.5876 | |

| 11 | KELWSMEK | 16.11 | 8 | 90 | 1049.5215 | |

| 12 | TAAGSL | 10.38 | 6 | 90 | 518.2700 | |

| 13 | LVLPGELAK | 18.33 | 9 | 90 | 938.5800 | Tian et al. [41] |

| 14 | EALE | 6.20 | 4 | 90 | 460.2169 | |

| 15 | TALTVVRN | 14.20 | 8 | 90 | 872.5079 | |

| 16 | LAVMQQQQQQ | 13.55 | 10 | 89 | 1200.5920 | Tian et al. [41] |

| 17 | DLGGFFGFQR | 18.99 | 10 | 89 | 1142.5508 | Picariello et al. [37] |

| 18 | SPKMAKNVD | 13.08 | 9 | 89 | 988.5012 | |

| 19 | DNLQGLTKP | 15.37 | 9 | 89 | 984.5240 | |

| 20 | PPPVHDTD | 4.46 | 8 | 89 | 876.3977 | Tian et al. [41] |

| 21 | PPVPHDTD | 4.30 | 8 | 89 | 876.3977 | Tian et al. [41] |

| 22 | ELQTSVR | 9.78 | 7 | 89 | 831.4450 | |

| 23 | LPEDAKVE | 13.19 | 8 | 88 | 899.4600 | Tian et al. [41] |

| 24 | HAVSEGTKAVT | 4.73 | 11 | 87 | 1098.5669 | Tian et al. [41] |

| 25 | SSQGLELSHVFHKS | 16.89 | 14 | 87 | 1554.7791 | |

| 26 | LPGELAK | 14.22 | 7 | 87 | 726.4276 | Tian et al. [41] |

| 27 | AHQQQVPVEVMR | 18.09 | 12 | 86 | 1420.7246 | |

| 28 | PMAPLPRSGEP | 15.91 | 11 | 86 | 1150.5803 | Picariello et al. [37] |

| 29 | TVSGF | 15.41 | 5 | 86 | 509.2485 | |

| 30 | SSLF | 18.10 | 4 | 86 | 452.2271 | |

| 31 | LNFDPNR | 15.74 | 7 | 86 | 874.4297 | Tian et al. [41] |

| 32 | PPPVHDFMNE | 4.41 | 10 | 86 | 1181.5176 | |

| 33 | ELRVR | 10.55 | 5 | 86 | 671.4078 | |

| 34 | EVNNVGQSGLMD | 16.34 | 12 | 85 | 1261.5608 | |

| 35 | ATPCCAEELER | 16.22 | 11 | 85 | 1220.5166 | |

| 36 | VAVARTPTVG | 14.57 | 10 | 85 | 969.5607 | |

| 37 | EAGY | 3.79 | 4 | 85 | 438.1750 | |

| 38 | LALDTRVG | 16.39 | 8 | 85 | 843.4814 | Tian et al. [41] |

| 39 | PMAPLPR | 15.47 | 7 | 85 | 780.4316 | |

| 40 | LDTRVGV | 15.14 | 7 | 85 | 758.4286 | Tian et al. [41] |

| 41 | RVALVY | 16.05 | 6 | 85 | 719.4330 | Tian et al. [41] |

| No. | Peptide | Peptide Ranker Score | No. | Peptide | Peptide Ranker Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DLGGFFGFQR | 0.8736 | 21 | SPKMAKNVD | 0.1683 |

| 2 | PMAPLPR | 0.8565 | 22 | TAAGSL | 0.1628 |

| 3 | SSLF | 0.8145 | 23 | LALDTRVG | 0.1545 |

| 4 | PPPVHDFMNE | 0.7050 | 24 | LVLPGELAK | 0.1488 |

| 5 | FDRLQ | 0.5909 | 25 | VAVARTPTVG | 0.1275 |

| 6 | PMAPLPRSGEP | 0.5780 | 26 | EVNNVGQSGLMD | 0.1166 |

| 7 | LASQLGLGGLSSL | 0.4581 | 27 | ALDTRVGV | 0.1162 |

| 8 | SSQGLELSHVFHKS | 0.4439 | 28 | RVALVY | 0.1076 |

| 9 | PPPVHD | 0.4175 | 29 | ELRVR | 0.0990 |

| 10 | PPPVHDTD | 0.2941 | 30 | VAVAREVAVG | 0.0900 |

| 11 | STEWHLD | 0.2941 | 31 | QAAVGGQVVEK | 0.0833 |

| 12 | TVSGF | 0.2924 | 32 | LPEDAKVE | 0.0763 |

| 13 | MFALPVPSQPVD | 0.2698 | 33 | LDTRVGV | 0.0728 |

| 14 | ATPCCAEELER | 0.2616 | 34 | TDVRLS | 0.0723 |

| 15 | PPVPHDTD | 0.2565 | 35 | HAVSEGTKAVT | 0.0701 |

| 16 | AHQQQVPVEVMR | 0.2268 | 36 | LAVMQQQQQQ | 0.0597 |

| 17 | LPGELAK | 0.2245 | 37 | TALTVVRN | 0.0575 |

| 18 | DNLQGLTKP | 0.2083 | 38 | ELQTSVR | 0.0521 |

| 19 | KELWSMEK | 0.1888 | 39 | EALE | 0.0483 |

| 20 | EAGY | 0.1687 |

| No. | Peptide | Activity | Active Amino Acid Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DLGGFFGFQR | ACE inhibition | GF, FG, GG, LG, FQ |

| 2 | PMAPLPR | ACE inhibition | PLP, PR, PL, AP, MAP |

| 3 | SSLF | ACE inhibition | LF |

| 4 | PPPVHDFMNE | ACE inhibition | PP, DF, PPP |

| 5 | FDRLQ | ACE inhibition | RL, LQ |

| 6 | PMAPLPRSGEP | ACE inhibition | PLP, PR, PL, GEP, AP, GE, SG, MAP |

| 9 | Peptide | Toxin | GRAVY | Absorption | Excretion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BBB | HIA | CYP450 Inhibitory Promiscuity | ||||

| 1 | DLGGFFGFQR | Non-Toxin | −0.050 | 0.9493 | 0.7473 | −0.9658 |

| 2 | PMAPLPR | Non-Toxin | −0.257 | 0.9332 | −0.5054 | −0.9958 |

| 3 | SSLF | Non-Toxin | 1.250 | 0.9037 | 0.7437 | −0.9888 |

| 4 | PPPVHDFMNE | Non-Toxin | −0.960 | 0.7896 | 0.6805 | −0.9657 |

| 5 | FDRLQ | Non-Toxin | −0.980 | 0.6429 | 0.7473 | −0.9870 |

| 6 | PMAPLPRSGEP | Non-Toxin | −0.736 | 0.9399 | −0.4929 | −0.9953 |

| Peptide | T-Score | C-Score | Number of Hydrogen Bonds |

|---|---|---|---|

| DLGGFFGFQR | 10.96 | 4.0 | 9 |

| PPPVHDFMNE | 9.22 | 4.0 | 5 |

| FDRLQ | 8.98 | 4.0 | 11 |

| Peptide | Interaction Mode | ACE Residue |

|---|---|---|

| DLGGFFGFQR | Hydrogen bond | Cys352(3.11Å), Gln369(3.00Å), Val380(2.62Å), Pro407(3.09Å), His410(3.06Å), Gly408(2.33Å), Gly414(3.03Å) |

| Hydrophobic interaction | Thr166, Lys343, Val148, Thr150, Asp377, Val351, Pro163, Ala149, Gln160, Trp185, Phe512, Ser147, Tyr146, Thr372, Cys370, Lys368, Ile367, Ala381, Leu161, Ser355, Arg522, Ala356, Gly386, Ile413, Ala412, Met385, Ser526 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tian, W.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, Q.; Hu, S.; Yan, W.; Yue, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, C.; Kong, Q.; Sun, L. In Silico Screening of Bioactive Peptides in Stout Beer and Analysis of ACE Inhibitory Activity. Foods 2024, 13, 1973. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13131973

Tian W, Zhang C, Zheng Q, Hu S, Yan W, Yue L, Chen Z, Zhang C, Kong Q, Sun L. In Silico Screening of Bioactive Peptides in Stout Beer and Analysis of ACE Inhibitory Activity. Foods. 2024; 13(13):1973. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13131973

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Wenhui, Cui Zhang, Qi Zheng, Shumin Hu, Weiqiang Yan, Ling Yue, Zhijun Chen, Ci Zhang, Qiulian Kong, and Liping Sun. 2024. "In Silico Screening of Bioactive Peptides in Stout Beer and Analysis of ACE Inhibitory Activity" Foods 13, no. 13: 1973. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13131973

APA StyleTian, W., Zhang, C., Zheng, Q., Hu, S., Yan, W., Yue, L., Chen, Z., Zhang, C., Kong, Q., & Sun, L. (2024). In Silico Screening of Bioactive Peptides in Stout Beer and Analysis of ACE Inhibitory Activity. Foods, 13(13), 1973. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13131973