Strategies for Producing Low FODMAPs Foodstuffs: Challenges and Perspectives

Abstract

1. Introduction

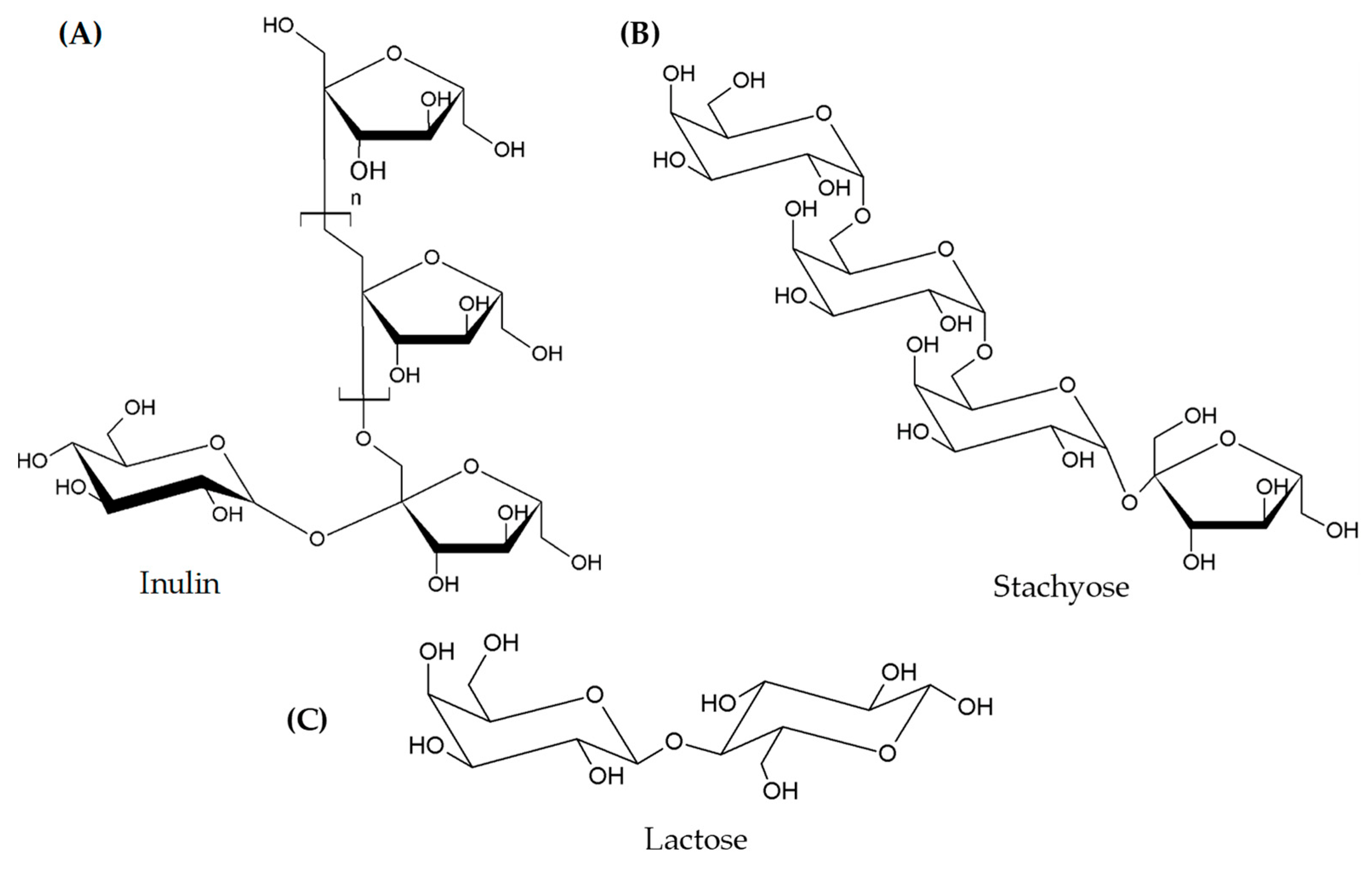

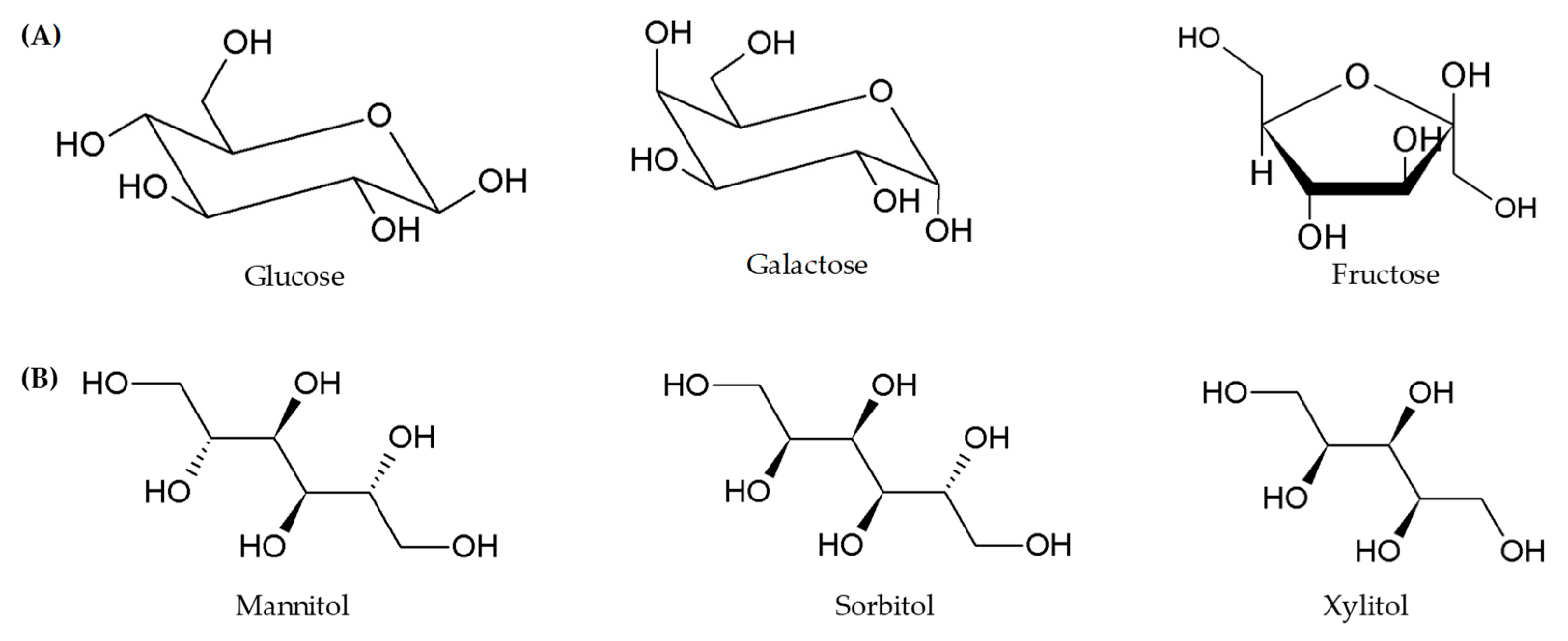

2. FODMAP Classifications

3. FODMAPs Content in Foods

4. Cereal Product Formulations with Low FODMAPs Content for Consumers with IBS

4.1. Approaches to Produce Low FODMAPs Cereal-Based Products

4.2. Ingredients Selection

4.3. Enzymatic FODMAPs Reduction

4.4. Reduction Mediated by Yeast and LAB Fermentation

5. New Approaches in Formulating Cereal-Based Products for IBS Management

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mearin, F.; Lacy, B.E.; Chang, L.; Chey, W.D.; Lembo, A.J.; Simren, M.; Spiller, R. Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterology 2016, 50, 1393–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, R.M.; Ford, A.C. Global Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Meta-analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 10, 712–721.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engsbro, A.L.; Simren, M.; Bytzer, P. Short-term stability of subtypes in the irritable bowel syndrome: Prospective evalua-tion using the Rome III classification. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 35, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Yang, Y.S.; Cui, L.H.; Zhao, K.B.; Zhang, Z.H.; Peng, L.H.; Guo, X.; Sun, G.; Shang, J.; Wang, W.F.; et al. Subtypes of irritable bowel syndrome on Rome III criteria: Amulticenter study. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 27, 760–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto-Sanchez, M.I.; Ford, A.; Avila, C.A.; Verdu, E.F.; Collins, S.M.; Morgan, D.; Moayyedi, P.; Bercik, P. Anxiety and Depression Increase in a Stepwise Manner in Parallel With Multiple FGIDs and Symptom Severity and Frequency. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 110, 1038–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gralnek, I.M.; Hays, R.D.; Kilbourne, A.; Naliboff, B.; Mayer, E.A. The impact of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of life. Gastroenterology 2000, 119, 654–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monnikes, H. Quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2011, 45, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, W.G.; Heaton, K.W.; Smyth, G.T.; Smyth, C. Irritable bowel syndrome in general practice: Prevalence, characteristics, and referral. Gut 2000, 46, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.; Boorman, J.; Cann, P.; Forbes, A.; Gomborone, J.; Heaton, K.; Hungin, P.; Kumar, D.; Libby, G.; Spiller, R.; et al. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines for the management of the irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 2000, 47, ii1–ii19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canavan, C.; West, J.; Card, T. Review article: The economic impact of the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 40, 1023–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxion-Bergemann, S.; Thielecke, F.; Abel, F.; Bergemann, R. Costs of Irritable Bowel Syndrome in the UK and US. Pharmacoeconomics 2006, 24, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Lembo, A.; Sultan, S. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Technical Review on the pharmacolog-ical management of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2014, 147, 1149–1172.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monsbakken, K.W.; Vandvik, P.O.; Farup, P.G. Perceived food intolerance in subjects with irritable bowel syndrome: Etiol-ogy, prevalence and consequences. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 60, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böhn, L.; Störsrud, S.; Simrén, M. Nutrient intake in patients with irritable bowel syndrome compared with the general population. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2013, 25, 23-e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, Y.A.; Bowyer, R.K.; Leach, H.; Gulia, P.; Horobin, J.; O’Sullivan, N.A.; Pettitt, C.; Reeves, L.B.; Seamark, L.; Williams, M.; et al. British Dietetic Association systematic review and evidence-based practice guidelines for the dietary management of irritable bowel syndrome in adults (2016 update). J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 29, 549–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moayyedi, P.; Quigley, E.M.; Lacy, B.E.; Lembo, A.J.; Saito, Y.A.; Schiller, L.R.; Soffer, E.E.; Spiegel, B.M.; Ford, A.C. The effect of fiber supplementation on irritable bowel syndrome: Asystematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 109, 1367–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagarajan, N.; Morden, A.; Bischof, D.; King, E.A.; Kosztowski, M.; Wick, E.C.; Stein, E.M. The role of fiber supplementation in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 27, 1002–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, P.; Corish, C.; O’Mahony, E.; Quigley, E.M.M. A dietary survey of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 27, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reding, K.W.; Cain, K.C.; Jarrett, M.E.; Eugenio, M.D.; Heitkemper, M.M. Relationship Between Patterns of Alcohol Consumption and Gastrointestinal Symptoms Among Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 108, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, I.; Trott, N.; Briggs, R.; North, J.R.; Hadjivassiliou, M.; Sanders, D.S. Efficacy of a gluten-free diet in subjects with irri-table bowel syndrome-diarrhea unaware of their HLA-DQ2/8 genotype. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 14, 696–703.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahnschaffe, U.; Schulzke, J.; Zeitz, M.; Ullrich, R. Predictors of Clinical Response to Gluten-Free Diet in Patients Diagnosed With Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007, 5, 844–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vazquez-Roque, M.I.; Camilleri, M.; Smyrk, T.; Murray, J.A.; Marietta, E.; O’Neill, J.; Carlson, P.; Lamsam, J.; Janzow, D.; Eckert, D.; et al. A controlled trial of gluten-free diet in patients with irritable bowel syn-drome-diarrhea: Effects on bowel frequency and intestinal function. Gastroenterology 2013, 144, 903–911.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesiekierski, J.; Peters, S.L.; Newnham, E.D.; Rosella, O.; Muir, J.G.; Gibson, P.R. No Effects of Gluten in Patients With Self-Reported Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity After Dietary Reduction of Fermentable, Poorly Absorbed, Short-Chain Carbohydrates. Na.t Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 145, 320–328.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staudacher, H.; Irving, P.; Lomer, M.; Whelan, K. Mechanisms and efficacy of dietary FODMAP restriction in IBS. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ispiryan, L.; Zannini, E.; Arendt, E.K. Characterization of the FODMAP-profile in cereal-product ingredients. J. Cereal Sci. 2020, 92, 102916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, P.R.; Shepherd, S.J. Personal view: Food for thought-western lifestyle and susceptibility to Crohn’s disease. The FODMAP hypothesis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005, 21, 1399–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, P.R.; Shepherd, S.J. Evidence-based dietary management of functional gastrointestinal symptoms: The FODMAP approach. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 25, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muir, J.G.; Shepherd, S.J.; Rosella, O.; Rose, R.; Barrett, J.S.; Gibson, P.R. Fructan and free fructose content of common Australian vegetables and fruit. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 6619–6627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, G.; Ureta, M.M.; Tymczyszyn, E.; Castilho, P.; Gomez-Zavaglia, A. Technological Aspects of the Production of Fructo and Galacto-Oligosaccharides. Enzymatic Synthesis and Hydrolysis. Front. Nutr. 2019, 6, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger-Grübel, C.; Hutter, S.; Hiestand, M.; Brenner, I.; Güsewell, S.; Borovicka, J. Treatment efficacy of a low FODMAP di-et compared to a low lactose diet in IBS patients: A randomized, cross-over designed study. Clin. Nutr. Espen 2020, 40, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Deng, Y.; Chu, H.; Cong, Y.; Zhao, J.; Pohl, D.; Misselwitz, B.; Fried, M.; Dai, N.; Fox, M. Prevalence and presenta-tion of lactose intolerance and effects on dairy product intake in healthy subjects and patients with irritable bowel syn-drome. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 11, 262–268.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouchoucha, M.; Fysekidis, M.; Rompteaux, P.; Raynaud, J.; Sabate, J.; Benamouzig, R. Lactose Sensitivity and Lactose Mal-absorption: The 2 Faces of Lactose Intolerance. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2021, 27, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rippe, J.M.; Angelopoulos, T.J. Sucrose, high-fructose corn syrup, and fructose, their metabolism and potential health ef-fects: What do we really know? Adv. Nutr. 2013, 4, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiNicolantonio, J.J.; Lucan, S.C. Is fructose malabsorption a cause of irritable bowel syndrome? Med. Hypotheses 2015, 85, 295–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenhart, A.; Chey, W.D. A Systematic Review of the Effects of Polyols on Gastrointestinal Health and Irritable Bowel Syn-drome. Adv. Nutr. 2017, 8, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaugerie, L.; Flourié, B.; Marteau, P.; Pellier, P.; Franchisseur, C.; Rambaud, J.-C. Digestion and absorption in the human intestine of three sugar alcohols. Gastroenterology 1990, 99, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Banares, F.; Esteve-Pardo, M.; De Leon, R.; Humbert, P.; Cabre, E.; Llovet, J.M.; Gassull, M.A. Sugar malabsorp-tion in functional bowel disease: Clinical implications. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1993, 88, 2044–2050. [Google Scholar]

- Hyams, J.S. Sorbitol Intolerance: An Unappreciated Cause of Functional Gastrointestinal Complaints. Gastroenterology 1983, 84, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperber, A.; Dumitrascu, D.; Fukudo, S.; Gerson, C.; Ghoshal, U.C.; Gwee, K.A.; Hungin, A.P.; Kang, J.-Y.; Minhu, C.; Schmulson, M.; et al. The global prevalence of IBS in adults remains elusive due to the heterogeneity of studies: A Rome Foundation working team literature review. Gut 2016, 66, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varney, J.; Barrett, J.; Scarlata, K.; Catsos, P.; Gibson, P.R.; Muir, J.G. FODMAPs: Food composition, defining cutoff values and international application. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 32 (Suppl. 1), 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Data from Monash University. Available online: https://monashfodmap.com/about-fodmap-and-ibs/ (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Liljebo, T.; Störsrud, S.; Andreasson, A. Presence of Fermentable Oligo-, Di-, Monosaccharides, and Polyols (FODMAPs) in commonly eaten foods: Extension of a database to indicate dietary FODMAP content and calculation of intake in the general population from food diary data. BMC Nutr. 2020, 6, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, J.S.; Gibson, P.R. Development and Validation of a Comprehensive Semi-Quantitative Food Frequency Questionnaire that Includes FODMAP Intake and Glycemic Index. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 110, 1469–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biesiekierski, J.R.; Rosella, O.; Rose, R.; Liels, K.; Barrett, J.S.; Shepherd, S.J.; Gibson, P.R.; Muir, J.G. Quantification of fructans, galacto-oligosacharides and other short-chain carbohydrates in processed grains and cereals. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2011, 24, 154–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haskå, L.; Nyman, M.; Andersson, R. Distribution and characterisation of fructan in wheat milling fractions. J. Cereal Sci. 2008, 48, 768–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, L.A.A.; Molognoni, L.; de Sá Ploêncio, L.A.; Costa, F.B.M.; Daguer, H.; Dea Lindner, J.D. Use of sourdough fer-mentation to reducing FODMAPs in breads. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245, 1183–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoš, K.; Mustač, N.; Varga, K.; Drakula, S.; Voučko, B.; Ćurić, D.; Novotni, D. Development of High-Fibre and Low-FODMAP Crackers. Foods 2022, 11, 2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habuš, M.; Mykolenko, S.; Iveković, S.; Pastor, K.; Kojić, J.; Drakula, S.; Ćurić, D.; Novotni, D. Bioprocessing of Wheat and Amaranth Bran for the Reduction of Fructan Levels and Application in 3D-Printed Snacks. Foods 2022, 11, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, J.U.; Steiner, D.; Longin, C.F.H.; Würschum, T.; Schweiggert, R.M.; Carle, R. Wheat and the irritable bowel syn-drome-FODMAP levels of modern and ancient species and their retention during bread making. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 25, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, J.; Struyf, N.; Bautil, A.; Bakeeva, A.; Chmielarz, M.; Lyly, M.; Herrera-Malaver, B.; Passoth, V.; Verstrepen, K.J.; Courtin, C.M. The Potential of Kluyveromyces marxianus to Produce Low-FODMAP Straight-Dough and Sourdough Bread: A Pilot-Scale Study. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2021, 14, 1920–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzler, J.J.; Ispiryan, L.; Gallagher, E.; Sahin, A.W.; Zannini, E.; Arendt, E.K. Enzymatic degradation of FODMAPS via appli-cation of β-fructofuranosidases and α-galactosidases-A fundamental study. J. Cereal Sci. 2020, 95, 102993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyyssölä, A.; Nisov, A.; Lille, M.; Nikinmaa, M.; Rosa-Sibakov, N.; Ellilä, S.; Valkonen, M.; Nordlund, E. Enzymatic reduc-tion of galactooligosaccharide content of faba bean and yellow pea ingredients and food products. Future Foods 2021, 4, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ispiryan, L.; Kuktaite, R.; Zannini, E.; Arendt, E.K. Fundamental study on changes in the FODMAP profile of cereals, pseudo-cereals, and pulses during the malting process. Food Chem. 2020, 343, 128549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo, A.; Mora, C.; Mojica, L. Thermal and enzymatic treatments reduced α-galactooligosaccharides in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) flour. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2019, 43, e14273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struyf, N.; Van der Maelen, E.; Hemdane, S.; Verspreet, J.; Verstrepen, K.J.; Courtin, C.M. Bread dough and baker’s yeast: An uplifting synergy. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2017, 16, 850–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Struyf, N.; Vandewiele, H.; Herrera-Malaver, B.; Verspreet, J.; Verstrepen, K.J.; Courtin, C.M. Kluyveromyces marxianus yeast enables the production of low FODMAP whole wheat breads. Food Microbiol. 2018, 76, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurent, J.; Timmermans, E.; Struyf, N.; Verstrepen, K.J.; Courtin, C.M. Variability in yeast invertase activity determines the extent of fructan hydrolysis during wheat dough fermentation and final FODMAP levels in bread. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 326, 108648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraberger, V.; Call, L.M.; Domig, K.J.; D’Amico, S. Applicability of yeast fermentation to reduce fructans and other FOD-MAPs. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longin, C.; Beck, H.; Gütler, A.; Gütler, H.; Heilig, W.; Zimmermann, J.; Bischoff, S.; Würschum, T. Influence of wheat variety and dough preparation on FODMAP content in yeast-leavened wheat breads. J. Cereal Sci. 2020, 95, 103021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pejcz, E.; Spychaj, R.; Gil, Z. Technological Methods for Reducing the Content of Fructan in Wheat Bread. Foods 2019, 8, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pejcz, E.; Spychaj, R.; Gil, Z. Technological methods for reducing the content of fructan in rye bread. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2020, 246, 1839–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewry, P.R.; America, A.H.; Lovegrove, A.; Wood, A.J.; Plummer, A.; Evans, J.; Broeck, H.C.V.D.; Gilissen, L.; Mumm, R.; Ward, J.L.; et al. Comparative compositions of metabolites and dietary fibre components in doughs and breads produced from bread wheat, emmer and spelt and using yeast and sourdough processes. Food Chem. 2021, 374, 131710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laatikainen, R.; Koskenpato, J.; Hongisto, S.-M.; Loponen, J.; Poussa, T.; Huang, X.; Sontag-Strohm, T.; Salmenkari, H.; Korpela, R. Pilot Study: Comparison of Sourdough Wheat Bread and Yeast-Fermented Wheat Bread in Individuals with Wheat Sensitivity and Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M.; Sciurba, E. Determination of FODMAP contents of common wheat and rye breads and the effects of processing on the final contents. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2020, 247, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albiac, M.A.; Di Cagno, R.; Filannino, P.; Cantatore, V.; Gobbetti, M. How fructophilic lactic acid bacteria may reduce the FODMAPs content in wheat-derived baked goods: A proof of concept. Microb. Cell Factories 2020, 19, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Q.; Loponen, J.; Ganzle, M.G. Characterization of the extracellular fructanase FruA in Lactobacillus crispatus and its con-tribution to fructan hydrolysis in breadmaking. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 8637–8647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joehnke, M.S.; Jeske, S.; Ispiryan, L.; Zannini, E.; Arendt, E.K.; Bez, J.; Petersen, I.L. Nutritional and anti-nutritional proper-ties of lentil (Lens culinaris) protein isolates prepared by pilot-scale processing. Food Chem. X 2021, 9, 100112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gélinas, P.; McKinnon, C.; Gagnon, F. Fructans, water-soluble fibre and fermentable sugars in bread and pasta made with ancient and modern wheat. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 51, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escarnot, E.; Dornez, E.; Verspreet, J.; Agneessens, R.; Courtin, C.M. Quantification and visualization of dietary fibre com-ponents in spelt and wheat kernels. J. Cereal Sci. 2015, 62, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cairano, M.; Condelli, N.; Caruso, M.C.; Cela, N.; Tolve, R.; Galgano, F. Use of Underexploited Flours for the Reduction of Glycaemic Index of Gluten-Free Biscuits: Physicochemical and Sensory Characterization. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2021, 14, 1490–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaoli, X.; Liyi, Y.; Shuang, H.; Wei, L.; Yi, S.; Hao, M.; Jusong, Z.; Xiaoxiong, Z. Determination of oligosaccharide contents in 19 cultivars of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L) seeds by high performance liquid chromatography. Food Chem. 2008, 111, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhise, S.; Kaur, A. Baking quality, sensory properties and shelf life of bread with polyols. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 51, 2054–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenny, S.; Wehrle, K.; Stanton, C.; Arendt, E.K. Incorporation of dairy ingredients into wheat bread: Effects on dough rhe-ology and bread quality. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2000, 210, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzler, J.J.; Sahin, A.W.; Gallagher, E.; Zannini, E.; Arendt, E.K. Investigation of different dietary-fibre-ingredients for the design of a fibre enriched bread formulation low in FODMAPs based on wheat starch and vital gluten. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 1939–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelsang-O’Dwyer, M.; Petersen, I.L.; Joehnke, M.S.; Sørensen, J.C.; Bez, J.; Detzel, A.; Busch, M.; Krueger, M.; O’Mahony, J.A.; Arendt, E.K.; et al. Comparison of Faba Bean Protein Ingredients Produced Using Dry Fractionation and Isoelectric Precipitation: Techno-Functional, Nutritional and Environmental Performance. Foods 2020, 9, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ispiryan, L.; Zannini, E.; Arendt, E.K. FODMAP modulation as a dietary therapy for IBS: Scientific and market perspective. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2022, 21, 1491–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyyssölä, A.; Ellilä, S.; Nordlund, E.; Poutanen, K. Reduction of FODMAP content by bioprocessing. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 99, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loponen, J.; Mikola, M.; Sibakov, J. Enzyme Exhibiting Fructan Hydrolase Activity. U.S. Patent 10,716,308, 21 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Loponen, J.; Gänzle, M.G. Use of Sourdough in Low FODMAP Baking. Foods 2018, 7, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmus, I.-M.; Copolovici, D.; Copolovici, L.; Ciobica, A.; Gorgan, D.L. Biomolecules from Plant Wastes Potentially Relevant in the Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Co-Occurring Symptomatology. Molecules 2022, 27, 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousdouni, P.; Kandyliari, A.; Koutelidakis, A.E. Probiotics and Phytochemicals: Role on Gut Microbiota and Efficacy on Irritable Bowel Syndrome, Functional Dyspepsia, and Functional Constipation. Gastrointest. Disord. 2022, 4, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Quigley, E.M. Diet and irritable bowel syndrome. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2015, 31, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fifi, A.C.; Axelrod, C.H.; Chakraborty, P.; Saps, M. Herbs and spices in the treatment of functional gastrointestinal disor-ders: A review of clinical trials. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingrosso, M.R.; Ianiro, G.; Nee, J.; Lembo, A.J.; Moayyedi, P.; Black, C.J.; Ford, A.C. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Efficacy of peppermint oil in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 56, 932–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, D.; Wang, Y.; Wen, X.; Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Feng, Y.; Li, B.; et al. Functional foods and intestinal homeostasis: The perspective of in vivo evidence. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 111, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozu, T.; Miyagishi, S.; Ishioh, M.; Takakusaki, K.; Okumura, T. Phlorizin attenuates visceral hypersensitivity and colonic hyperpermeability in a rat model of irritable bowel syndrome. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 139, 111649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, H.-F.; Venkatakrishnan, K.; Golovinskaia, O.; Wang, C.-K. Gastroprotective Effects of Polyphenols against Various Gastro-Intestinal Disorders: A Mini-Review with Special Focus on Clinical Evidence. Molecules 2021, 26, 2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hekmatdoost, A.; Jalili, M.; Vahedi, H.; Poustchi, H. Effects of Vitamin D supplementation in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 10, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tazzyman, S.; Richards, N.; Trueman, A.R.; Evans, A.L.; Grant, V.A.; Garaiova, I.; Plummer, S.F.; Williams, E.; Corfe, B.M. Vitamin D associates with improved quality of life in participants with irritable bowel syndrome: Outcomes from a pilot trial. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2015, 2, e000052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalili, M.; Vahedi, H.; Poustchi, H.; Hekmatdoost, A. Soy isoflavones and cholecalciferol reduce inflammation, and gut permeability, without any effect on antioxidant capacity in irritable bowel syndrome: A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2019, 34, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classes | Examples |

|---|---|

| Oligosaccharides | Fructans (FOS), Galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS) |

| Polysaccharides | Lactose |

| Monosaccharides | Fructose |

| Polyols | Sorbitol, mannitol, xylitol, erythritol, polydextrose, and maltitol |

| Food | Low FODMAPs | High FODMAPs |

|---|---|---|

| Fruits | Kiwifruit, blueberry, banana, mandarin, orange, passionfruit, grapefruit. | Peaches, apples, pears, watermelon, cherries, mango, apricots. |

| Vegetables | Carrot, celery, lettuce, eggplant, zucchini, green beans, bok choy. | Asparagus, Brussels sprout, cabbage, fennel, mushrooms, onion, garlic. |

| Dairy | Brie/camembert cheese, feta cheese, lactose-free milk. | Cow, sheep and goat milk, ice cream, yoghurt, ricotta, cottage. |

| Grain/cereals | Gluten-free bread/cereal products, sourdough spelt bread, quinoa/rice/corn pasta. | Pasta, wheat bread, biscuits, couscous. |

| Sweeteners | Maple, rice malt and golden syrups, sucrose. | Honey, high fructose corn syrup, sorbitol, mannitol, xylitol. |

| Approaches | Product | Type of Flour | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ingredient selection and fermentation time | Bread | Wheat | Prolonged proofing time (>4 h) ↓ FODMAPs content up to 90% | Ziegler et al. [49] |

| Ingredients selection | Cracker | Wholemeal, buckwheat, millet, and white maize | High fibre, low-FODMAP product | Radoš et al. [47] |

| Enzymatic (β-fructofuranosidases and α-galactosidases) | Flour | Wholemeal wheat and lentil flours (degradation on FODMAPs extract) | Inulinase degraded over 90% GOS and fructans α—galoctosidase degrade 100% GOS invertase low degradation yield | Atzler et al. [51] |

| Enzymatic (α-GOS) | High moisture meat analogues Crackers Spoonable product | Faba bean and yellow been | ↓ GOS over 90% | Nyyssölä et al. [52] |

| Enzymatic (activation of endogenous enzymes by malting) | Grains | Spring malting barley, wheat, chickpeas, oat, lentils, buckwheat | Malting ↓ 80–90%GOS in lentils and chickpeas—fructans not synthetized in oat barley and wheat malts slightly higher fructans content | Ispyrian et al. [53] |

| Enzymatic (α-galactosidases) and soaking treatmentand thermal treatment | Flour | Common bean | Ezymatic hydrolysis (α-GOS) and soaking and thermal treatment ↓ GOS up to 97.6% | Escobendo et al. [54] |

| Yeast fermentation (inulinase producer) | Bread | Wheat flour | Kluyveromyces marxiaus strain ↓ 90% fructans level; Saccharomices cerevies ↓ 56% reduction; co-culture of the two-strain leads to a bread low FODMAP and good loaf volume | Struyf et al. [55] |

| Yeast fermentation (30 K. marxianus strains) | Bread | Wheat | Kluyveromyces marxianus strain CBS6014 can degrade more than 90% of the fructans | Struyf et al. [56] |

| Yeast fermentation (28 S. cerevisiae strains) | Bread | Wholewheat | Final fructan level of 0.3% dm, Strains with a low invertase activity yielded fructan levels around 0.6% dm. The non-bakery strains produced lower levels of CO2 in the bread | Laurent et al. [57] |

| Yeast fermentation | Model system | Different rye and sourdough as yeast source | Saccharomyces cerevisiae isolated from Austrian traditional sourdough showed the highest degree of degradation of the total fructan content and the highest gas building capacity, followed by Torulaspora delbrueckii | Fraberger et al. [58] |

| Yeast fermentation and fermentation time | Bread | Wheat (21 varieties) | Different wheat varieties differ up to 5 times in their potential to form FODMAPs in bread. FODAMPs content tend to be lower in long fermentation but not significant FODMAPs reduction >65% | Longin et al. [59] |

| Yeast fermentation and enzymatic (inulinase) | 3D printed snack | Wheat and amaranth bran | ↓ fructan content up to 93% | Habuš et al. [48] |

| Yeast and LAB (sourdough) fermentation and ingredients selection | Bread | Light and whole wheat | Sourdough and extended fermentation time ↓ fructans content use of light flour ↓ fructans content | Pejcz et al. [60] |

| Yeast and LAB fermentation (sourdough) and ingredients selection and fermentation time | Bread | Rye flour (endosperm and whole meal | Sourdough ↓ fructans content— prolonged fermentation time no effect on fructans content | Pejcz et al. [61] |

| Yeast and LAB (sourdough) fermentation | Bread | Wheat, rye, emmer | Wheat bread ↑ fibre and fructan contents compared to other flours- Yeast fermentation ↑ reduction of fructans and raffinose | Shewry et al. [62] |

| Yeast and LAB (sourdough) fermentation | Bread | Wheat flour | Sourdough ↓ FODMAPs-sourdough bread not best tolerated by IBS patients than yest fermented | Laatikainen et al. [63] |

| LAB (sourdough) and fermentation time | Bread | Wheat flour and rye flour (wholemeal and refined) | Prolonged proofing time ↓ fructans content sourdough changed FODMAPs composition by ↓ fructans content and ↑ mannitol content-refined wheat flour bread meets low FODMAPs criteria—rye and whole meal wheat flour high FODMAPs regardless of processing condition employed | Schmidt and Sciurba [64] |

| LAB fermentation (25 fructophilic lactic acid bacteria strains) | Bread/dough | Durum wheat | Fermenting dough resulted in lower loaf volumes | Acín Albiac et al. [65] |

| LAB (sourdough) fermentation | Bread | Wheat | Sourdough ↓ of fructans up to 69–75% | Menezes et al. [46] |

| LAB (sourdough) fermentation + Lactobacillus crispatus | Bread | Rye and wheat flour | Sourdough fermentation with L. crispatus ↓ fructans more than 90% Conventional sourdough fermentation ↓ fructans (65–70%) | Li et al. [66] |

| Other approaches isoelectric precipitation and ultrafiltration | Lentil protein isolate | Lentil | ↓ GOS 58% isoelectric precipitation ↓ GOS 91% ultrafiltration | Joehnke et al. [67] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Galgano, F.; Mele, M.C.; Tolve, R.; Condelli, N.; Di Cairano, M.; Ianiro, G.; D’Antuono, I.; Favati, F. Strategies for Producing Low FODMAPs Foodstuffs: Challenges and Perspectives. Foods 2023, 12, 856. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12040856

Galgano F, Mele MC, Tolve R, Condelli N, Di Cairano M, Ianiro G, D’Antuono I, Favati F. Strategies for Producing Low FODMAPs Foodstuffs: Challenges and Perspectives. Foods. 2023; 12(4):856. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12040856

Chicago/Turabian StyleGalgano, Fernanda, Maria Cristina Mele, Roberta Tolve, Nicola Condelli, Maria Di Cairano, Gianluca Ianiro, Isabella D’Antuono, and Fabio Favati. 2023. "Strategies for Producing Low FODMAPs Foodstuffs: Challenges and Perspectives" Foods 12, no. 4: 856. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12040856

APA StyleGalgano, F., Mele, M. C., Tolve, R., Condelli, N., Di Cairano, M., Ianiro, G., D’Antuono, I., & Favati, F. (2023). Strategies for Producing Low FODMAPs Foodstuffs: Challenges and Perspectives. Foods, 12(4), 856. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12040856