Is Eating Less Meat Possible? Exploring the Willingness to Reduce Meat Consumption among Millennials Working in Polish Cities

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

- A.

- What phase of change in terms of reducing meat consumption are the respondents in?

- B.

- Does willingness to reduce meat intake depend on socio-demographic variables?

- C.

- Is meat consumption frequency linked to the respondents’ self-assessment phase of change?

- D.

- Are behavioral phases linked to total MAQ scores and scores in each of the four categories of attachment?

2.2. Participants

2.3. Questionnaire

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Frequency of Meat Consumption

2.4.2. Phases of Change of Meat Consumption

2.4.3. Willingness to Limit Meat Consumption

2.4.4. Meat Attachment Questionnaire (MAQ)

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

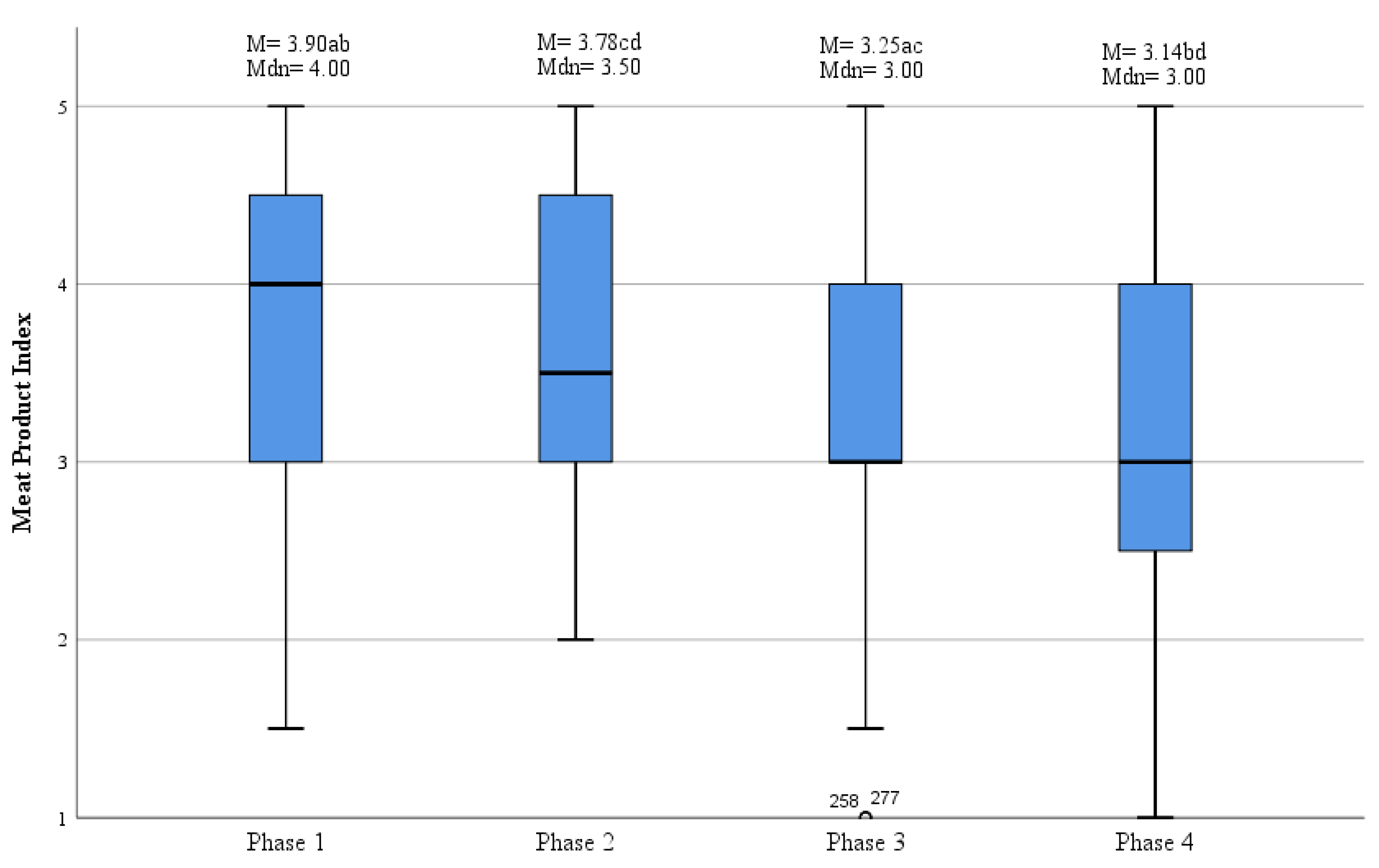

3.1. Frequency of Meat Consumption

Phases of Change

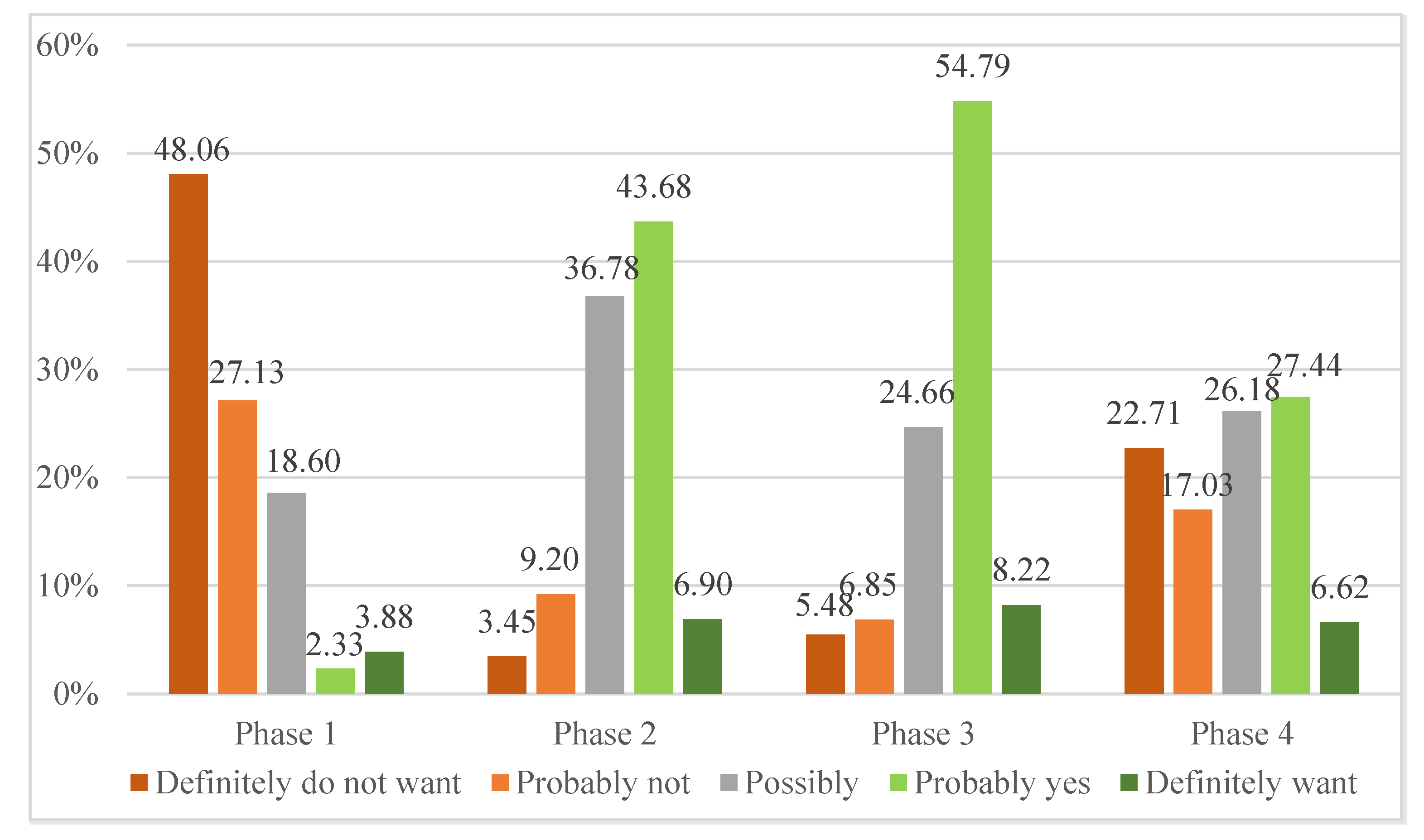

3.2. Willingness to Limit Meat Consumption

3.3. Socio-Demographic Variables

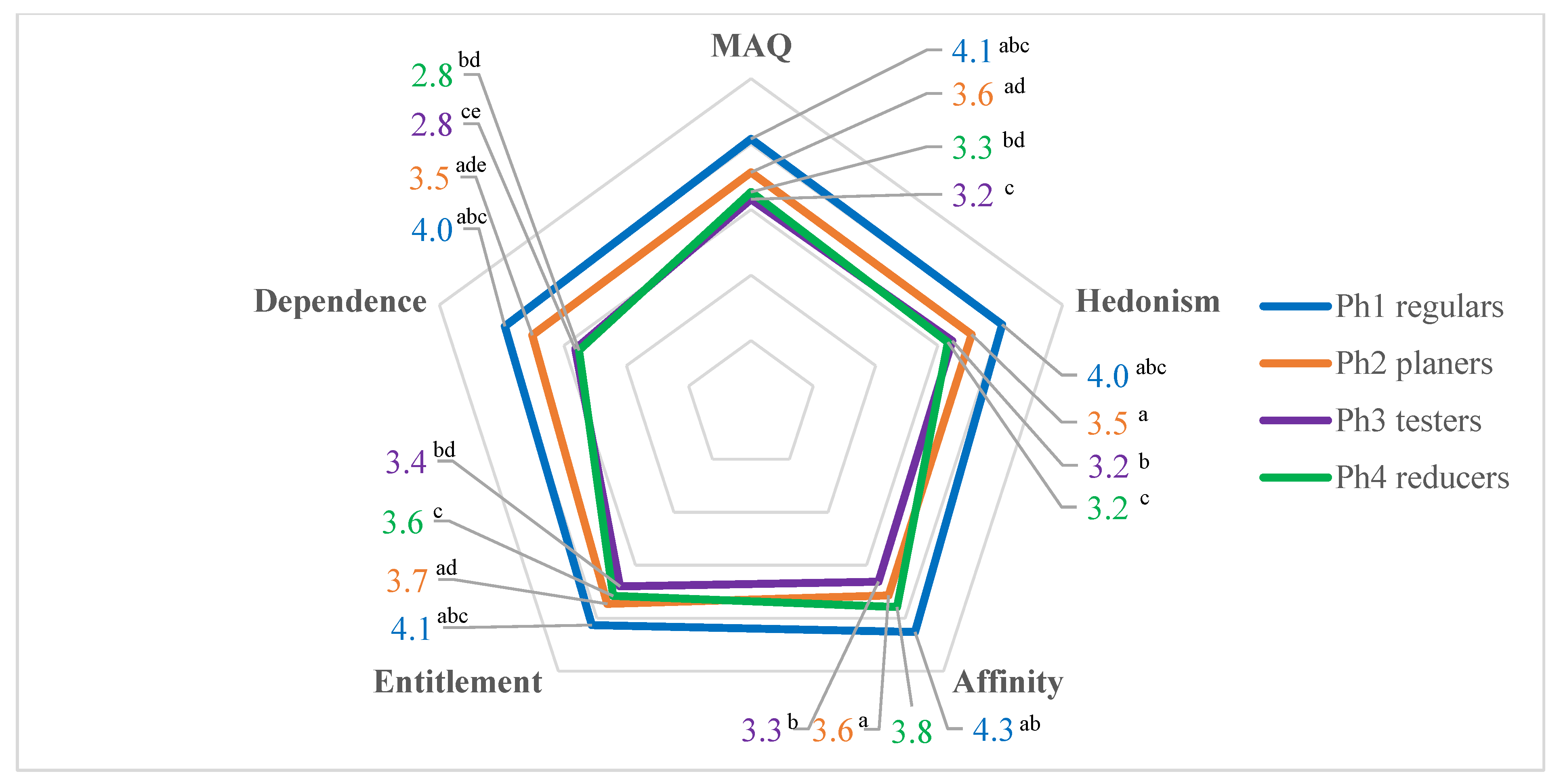

3.4. MAQ Factors

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Swinburn, B.A.; Kraak, V.I.; Allender, S.; Atkins, V.J.; Baker, P.I.; Bogard, J.R.; Brinsden, H.; Calvillo, A.; De Schutter, O.; Devarajan, R.; et al. The Global Syndemic of Obesity, Undernutrition, and Climate Change: The Lancet Commission report. Lancet 2019, 393, 791–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; WHO. Sustainable Healthy Diets; FAO and WHO: Rome, Italy, 2019; ISBN 9789251318751. [Google Scholar]

- Springmann, M.; Spajic, L.; Clark, M.A.; Poore, J.; Herforth, A.; Webb, P.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. The healthiness and sustainability of national and global food based dietary guidelines: Modelling study. BMJ 2020, 370, 2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Koerber, K.; Bader, N.; Leitzmann, C. Conference on “Sustainable food consumption” Wholesome Nutrition: An example for a sustainable diet. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017, 76, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- FAO. Sustainable Diets and Biodiveristy; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Aiking, H.; de Boer, J. The next protein transition. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 105, 515–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich Böll Stiftung; Friends of the Earth Europe, Bund für Umwelt und Naturschutz. Meat Atlas; Heinrich Böll Foundation and Friends of the Earth Europe: Berlin, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Drewnowski, A.; Finley, J.; Hess, J.M.; Ingram, J.; Miller, G.; Peters, C. Toward healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 4, nzaa083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, N.J. A brief history of meat in the human diet and current health implications. Meat Sci. 2018, 144, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, F.; Praet, I. Meat traditions. The co-evolution of humans and meat. Appetite 2015, 90, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Global Livestock Environmental Assessment Model: Model Description; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski, W.; Górska-Warsewicz, H.; Kulykovets, O. Meat, Meat Products and Seafood as Sources of Energy and Nutrients in the Average Polish Diet. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wyness, L. The role of red meat in the diet: Nutrition and health benefits. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2016, 75, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pereira, P.M.D.C.C.; Vicente, A.F.D.R.B. Meat nutritional composition and nutritive role in the human diet. Meat Sci. 2013, 93, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koch, F.; Heuer, T.; Krems, C.; Claupein, E. Meat consumers and non-meat consumers in Germany: A characterisation based on results of the German National Nutrition Survey II. J. Nutr. Sci. 2019, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Al-Shaar, L.; Satija, A.; Wang, D.D.; Rimm, E.B.; Smith-Warner, S.A.; Stampfer, M.J.; Hu, F.B.; Willett, W.C. Red meat intake and risk of coronary heart disease among US men: Prospective cohort study. BMJ 2020, 371, m4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, R.; Cross, A.J.; Graubard, B.I.; Leitzmann, M.F.; Schatzkin, A. Meat intake and mortality: A prospective study of over half a million people. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009, 169, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Lin, X.; Ouyang, Y.Y.; Liu, J.; Zhao, G.; Pan, A.; Hu, F.B. Red and processed meat consumption and mortality: Dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 893–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Richi, E.B.; Baumer, B.; Conrad, B.; Darioli, R.; Schmid, A.; Keller, U. Health risks associated with meat consumption: A review of epidemiological studies. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2015, 85, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrmann, S.; Overvad, K.; Bueno-de-Mesquita, H.B.; Jakobsen, M.U.; Egeberg, R.; Tjønneland, A.; Nailler, L.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C.; Clavel-Chapelon, F.; Krogh, V.; et al. Meat consumption and mortality-results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. BMC Med. 2013, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization; IARC. Monographs Evaluate Consumption of Red Meat and Processed Meat and Cancer Risk; International Agency for Research on Cancer and World Health Organisation: Lyon, France, 2015; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Hestermann, N.; Le Yaouanq, Y.; Treich, N.; Graça, J.; Calheiros, M.M.; Oliveira, A.; Dowsett, E.; Semmler, C.; Bray, H.; Ankeny, R.A.; et al. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer: A Global Perspective. Contin. Updat. Proj. Expert Rep. 2018, 123, 113. [Google Scholar]

- Papier, K.; Fensom, G.K.; Knuppel, A.; Appleby, P.N.; Tong, T.Y.N.; Schmidt, J.A.; Travis, R.C.; Key, T.J.; Perez-cornago, A. Meat consumption and risk of 25 common conditions: Outcome-wide analyses in 475,000 men and women in the UK Biobank study. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2013 Risk Factors Collaborators; GBD 2013 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risk factors or clusters of risks in 188 countries, 1990-2013: A systematic analysis for the Gl. Lancet 2013, 386, 2287–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Charles, H.; Godfray, J.; Aveyard, P.; Garnett, T.; Hall, J.W.; Key, T.J.; Lorimer, J.; Pierrehumbert, R.T.; Scarborough, P.; Springmann, M.; et al. Meat consumption, health, and the environment. Science 2018, 361, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hedenus, F.; Wirsenius, S.; Johansson, D.J.A. The importance of reduced meat and dairy consumption for meeting stringent climate change targets. Clim. Chang. 2014, 124, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aleksandrowicz, L.; Green, R.; Joy, E.J.M.; Smith, P.; Haines, A. The impacts of dietary change on greenhouse gas emissions, land use, water use, and health: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scarborough, P.; Appleby, P.N.; Mizdrak, A.; Briggs, A.D.M.; Travis, R.C.; Bradbury, K.E.; Key, T.J. Dietary greenhouse gas emissions of meat-eaters, fish-eaters, vegetarians and vegans in the UK. Clim. Chang. 2014, 125, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mottet, A.; de Haan, C.; Falcucci, A.; Tempio, G.; Opio, C.; Gerber, P. Livestock: On our plates or eating at our table? A new analysis of the feed/food debate. Glob. Food Sec. 2017, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Food Agriculture and Fisheries of Denmark. The Official Dietary Guidelines–Good for Health and Climate, 1st ed.; The Danish Veterinary and Food Administration: Glostrup, Denmark, 2021; ISBN 978-87-93147-44-7. [Google Scholar]

- Food-based dietary guidelines—Poland. Zalecenia Zdrowego Żywienia; Institute of Health: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- From Plate to Guide: What, Why and How for the Eatwell Model; Public Health England: London, UK, 2016.

- Statistics Poland. Household Budget Survey in 2020; Statistics Poland: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Poland. Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Poland 2020; Statistics Poland: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhubi-Bakija, F.; Bajraktari, G.; Bytyçi, I.; Mikhailidis, D.P.; Henein, M.Y.; Latkovskis, G.; Rexhaj, Z.; Zhubi, E.; Banach, M.; Alnouri, F.; et al. The impact of type of dietary protein, animal versus vegetable, in modifying cardiometabolic risk factors: A position paper from the International Lipid Expert Panel (ILEP). Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 255–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertzler, S.R.; Lieblein-Boff, J.C.; Weiler, M.; Allgeier, C. Plant proteins: Assessing their nutritional quality and effects on health and physical function. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruini, L.F.; Ciati, R.; Pratesi, C.A.; Marino, M.; Principato, L.; Vannuzzi, E. Working toward Healthy and Sustainable Diets: The “Double Pyramid Model” Developed by the Barilla Center for Food and Nutrition to Raise Awareness about the Environmental and Nutritional Impact of Foods. Front. Nutr. 2015, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ferreira, H.; Vasconcelos, M.; Gil, A.M.; Pinto, E. Benefits of pulse consumption on metabolism and health: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 61, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, J.; Wyatt, A.J. The role of pulses in sustainable and healthy food systems. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2017, 1392, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Considine, M.J.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Foyer, C.H. Nature’s pulse power: Legumes, food security and climate change. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 1815–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. The Future of Food and Agriculture Alternative Pathways to 2050; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Viguiliouk, E.; Blanco Mejia, S.; Kendall, C.W.C.; Sievenpiper, J.L. Can pulses play a role in improving cardiometabolic health? Evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2017, 1392, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- CBI. Which Trends Offer Opportunities or Pose Threats on the European Grains, Pulses and Oilseeds Market? CBI: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Weibel, C.; Ohnmacht, T.; Schaffner, D.; Kossmann, K. Reducing individual meat consumption: An integrated phase model approach. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 73, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, J.; Calheiros, M.M.; Oliveira, A. Attached to meat? (Un)Willingness and intentions to adopt a more plant-based diet. Appetite 2015, 95, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lentz, G.; Connelly, S.; Mirosa, M.; Jowett, T. Gauging attitudes and behaviours: Meat consumption and potential reduction. Appetite 2018, 127, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowsett, E.; Semmler, C.; Bray, H.; Ankeny, R.A.; Chur-Hansen, A. Neutralising the meat paradox: Cognitive dissonance, gender, and eating animals. Appetite 2018, 123, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Profeta, A.; Baune, M.C.; Smetana, S.; Bornkessel, S.; Broucke, K.; Van Royen, G.; Enneking, U.; Weiss, J.; Heinz, V.; Hieke, S.; et al. Preferences of german consumers for meat products blended with plant-based proteins. Sustainability 2021, 13, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhardt, J.; Olsen, A. Meat reduction in 5 to 8 years old children—A survey to investigate the role of parental meat attachment. Foods 2021, 10, 1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rejman, K.; Kaczorowska, J.; Halicka, E.; Laskowski, W. Do Europeans consider sustainability when making food choices? A survey of Polish city-dwellers. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 1330–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Szczebyło, A.; Rejman, K.; Halicka, E.; Laskowski, W. Towards more sustainable diets—Attitudes, opportunities and barriers to fostering pulse consumption in Polish cities. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttlar, B.; Walther, E. Escaping from the meat paradox: How morality and disgust affect meat-related ambivalence. Appetite 2022, 168, 105721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gradidge, S.; Zawisza, M.; Harvey, A.J.; McDermott, D.T. A structured literature review of the meat paradox. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2021, 16, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaltola, E. The Meat Paradox, Omnivore’s Akrasia, and Animal Ethics. Animals 2019, 9, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piazza, J.; Ruby, M.B.; Loughnan, S.; Luong, M.; Kulik, J.; Watkins, H.M.; Seigerman, M. Rationalizing meat consumption. The 4Ns. Appetite 2015, 91, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- de Boer, J.; Aiking, H. Prospects for pro-environmental protein consumption in Europe: Cultural, culinary, economic and psychological factors. Appetite 2018, 121, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eurostat Agricultural Production-Livestock and Meat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Agricultural_production_-_livestock_and_meat&oldid=427096#Meat_production (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Malek, L.; Umberger, W.J.; Goddard, E. Committed vs. uncommitted meat eaters: Understanding willingness to change protein consumption. Appetite 2019, 138, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, C.; Dohle, S.; Siegrist, M. Importance of cooking skills for balanced food choices. Appetite 2013, 65, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, E.J.; Crawford, D.; Worsley, A. Consumers’ readiness to eat a plant-based diet. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 60, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mullee, A.; Vermeire, L.; Vanaelst, B.; Mullie, P.; Deriemaeker, P.; Leenaert, T.; De Henauw, S.; Dunne, A.; Gunter, M.J.; Clarys, P.; et al. Vegetarianism and meat consumption: A comparison of attitudes and beliefs between vegetarian, semi-vegetarian, and omnivorous subjects in Belgium. Appetite 2017, 114, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, J.; Aiking, H. Strategies towards healthy and sustainable protein consumption: A transition framework at the levels of diets, dishes, and dish ingredients. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 73, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, M.; Kurzer, A.; Cienfuegos, C.; Guinard, J.X. Student consumer acceptance of plant-forward burrito bowls in which two-thirds of the meat has been replaced with legumes and vegetables: The Flexitarian FlipTM in university dining venues. Appetite 2018, 131, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filimonau, V.; Lemmer, C.; Marshall, D.; Bejjani, G. ‘Nudging’ as an architect of more responsible consumer choice in food service provision: The role of restaurant menu design. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 144, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stubbs, J.J.; Scott, S.E.; Duarte, C. Responding to food, environment and health challenges by changing meat consumption behaviours in consumers. Nutr. Bull. 2018, 43, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagevos, H.; Voordouw, J. Sustainability and meat consumption: Is reduction realistic? Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2013, 9, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbyshire, E.J. Flexitarian Diets and Health: A Review of the evidence-Based Literature. Front. Nutr. 2017, 3, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neff, R.A.; Edwards, D.; Palmer, A.; Ramsing, R.; Righter, A.; Wolfson, J. Reducing meat consumption in the USA: A nationally representative survey of attitudes and behaviours. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 21, 1835–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Graça, J.; Godinho, C.A.; Truninger, M. Reducing meat consumption and following plant-based diets: Current evidence and future directions to inform integrated transitions. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 91, 380–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kemper, J.A. Motivations, barriers, and strategies for meat reduction at different family lifecycle stages. Appetite 2020, 150, 104644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W.; Pérez-Cueto, F.J.A.; Barcellos, M.D.; Krystallis, A.; Grunert, K.G. European citizen and consumer attitudes and preferences regarding beef and pork. Meat Sci. 2010, 84, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat Comparative Price Levels for Food, Beverages and Tobacco. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Comparative_price_levels_for_food,_beverages_and_tobacco#Price_levels_for_bread_and_cereals.2C_meat.2C_fish_and_dairy_products (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Halicka, E.; Kaczorowska, J.; Rejman, K.; Szczebyło, A. Parental food choices and engagement in raising children’s awareness of sustainable behaviors in urban Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozin, P.; Hormes, J.M.; Faith, M.S.; Wansink, B. Is meat male? A quantitative multimethod framework to establish metaphoric relationships. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, M.; Wilson, M.S. A dual-process motivational model of attitudes towards vegetarians and vegans. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 49, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Special Eurobarometer-Food Safety in the EU; EFSA: European Union: Parma, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Maj, A. On the Perception of Linkages between Food Consumption and Health in Poland. Sociol. Anthropol. 2016, 4, 294–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- FAO. Sustainable Food Systems Concept and Framework; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vainio, A.; Irz, X.; Hartikainen, H. How effective are messages and their characteristics in changing behavioural intentions to substitute plant-based foods for red meat? The mediating role of prior beliefs. Appetite 2018, 125, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, F.; Dorsel, C.; Garnett, E.; Aveyard, P.; Jebb, S.A. Interventions targeting conscious determinants of human behaviour to reduce the demand for meat: A systematic review with qualitative comparative analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sanchez-Sabate, R.; Sabaté, J. Consumer Attitudes Towards Environmental Concerns of Meat Consumption: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vaillancourt, C.; Bédard, A.; Bélanger-Gravel, A.; Provencher, V.; Bégin, C.; Desroches, S.; Lemieux, S. Promoting Healthy Eating in Adults: An Evaluation of Pleasure-Oriented versus Health-Oriented Messages. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2019, 3, nzz012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laestadius, L.I.; Neff, R.A.; Barry, C.L.; Frattaroli, S. “We don’t tell people what to do”: An examination of the factors influencing NGO decisions to campaign for reduced meat consumption in light of climate change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 29, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Pulses: Nutritions Seeds for Sustainable Future; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- WWF. Planet-Based Diets. Available online: https://planetbaseddiets.panda.org/ (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- European Commission. Farm to Fork Strategy; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Research Question | Variables | Measurement Level and Type |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable Phase Model (PM) Descriptive factor Willingness to limit meat consumption | Phase 1: I have never considered reducing my meat consumption. Phase 2: I’ve considered reducing my meat consumption, but I haven’t yet put this plan into practice. Phase 3: I make sure I consume less meat occasionally. In the future it is my firm intention to do this on a regular basis. Phase 4: I take consuming little or no meat for granted. Q: Indicate your willingness to limit your consumption of meat on a scale from 1—definitely do not want, to 5—definitely want. |

| Meat Products Index (MPI) | The mean of the answers to two questions: Q1: How often do you usually eat meat? Q2: How often do you usually eat meat products, i.e., cold cuts, sausages, frankfurters, pates? Nominal scale: several times a day (5), once a day (4), several times a week (3), once a week (2), 1–3 times a month (1) |

| Socio-demographic variable Gender Size of household | Nominal: male, female Nominal: 1, 2, 3, 4, ≥5 people |

| 16 statements from the Meat Attachment Questionnaire grouped into four categories (hedonism, affinity, entitlement, dependence) | Q: Please indicate to what extent you agree with the following statements-five-point Likert scale: definitely not (1)–definitely yes (5) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szczebyło, A.; Halicka, E.; Rejman, K.; Kaczorowska, J. Is Eating Less Meat Possible? Exploring the Willingness to Reduce Meat Consumption among Millennials Working in Polish Cities. Foods 2022, 11, 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11030358

Szczebyło A, Halicka E, Rejman K, Kaczorowska J. Is Eating Less Meat Possible? Exploring the Willingness to Reduce Meat Consumption among Millennials Working in Polish Cities. Foods. 2022; 11(3):358. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11030358

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzczebyło, Agata, Ewa Halicka, Krystyna Rejman, and Joanna Kaczorowska. 2022. "Is Eating Less Meat Possible? Exploring the Willingness to Reduce Meat Consumption among Millennials Working in Polish Cities" Foods 11, no. 3: 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11030358

APA StyleSzczebyło, A., Halicka, E., Rejman, K., & Kaczorowska, J. (2022). Is Eating Less Meat Possible? Exploring the Willingness to Reduce Meat Consumption among Millennials Working in Polish Cities. Foods, 11(3), 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11030358