An Exploratory Study on the Relation between Companies’ Food Integrity Climate and Employees’ Food Integrity Behavior in Food Businesses

Abstract

:1. Introduction

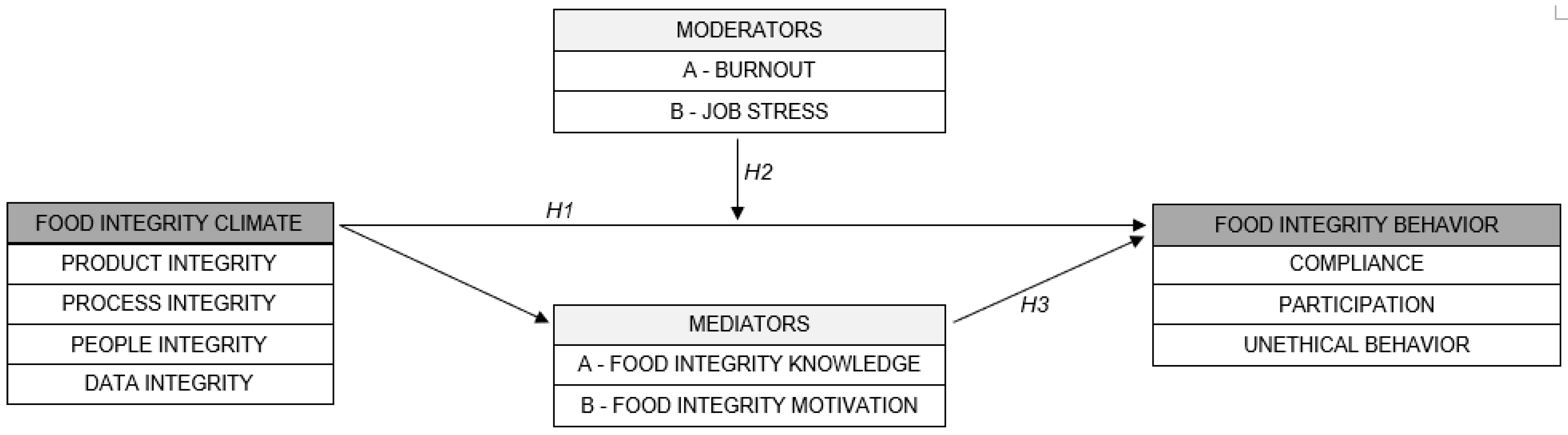

2. Conceptual Research Model

2.1. Food Integrity Behavior

2.1.1. Compliance

2.1.2. Participation

2.1.3. Unethical Pro-Organizational Behavior

2.2. Food Integrity Climate

2.3. Food Integrity Climate and Food Integrity Behavior

2.4. Moderators

2.4.1. Job Stress

2.4.2. Burnout

2.5. Mediators

2.5.1. Food Integrity Knowledge

2.5.2. Food Integrity Motivation

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Measurement Instruments

3.1.1. Food Integrity Climate Assessment

3.1.2. Food Integrity Behavior Assessment

3.1.3. Job Stress Assessment

3.1.4. Burnout Assessment

3.1.5. Food Integrity Knowledge Assessment

3.1.6. Food Integrity Motivation Assessment

3.1.7. Control Variables

3.2. Sample Selection

3.3. Data Collection

3.4. Data Processing and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.1.1. Demographics of Respondents

4.1.2. Univariate Results

4.1.3. Bivariate Results

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

4.2.1. Hypothesis 1: Relation between Food Integrity Climate and Food Integrity Behavior

4.2.2. Hypothesis 2A: Job Stress as a Moderator

4.2.3. Hypothesis 2B: Burnout as a Moderator

4.2.4. Hypothesis 3A: Food Integrity Knowledge as a Mediator

4.2.5. Hypothesis 3B: Food Integrity Motivation as a Mediator

5. Discussion

6. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| PRODUCT INTEGRITY Product integrity means that a food product is safe for human consumption, of quality, genuine, with pure and non-adulterated ingredients from recognized and true origins (e.g., product components are not substituted or diluted with cheaper ingredients of lower value or from non-declared origins). | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Not agree nor disagree | Agree | Strongly agree | |

| Q1 | In my company, leaders set clear objectives and goals on how to achieve product integrity (e.g., leaders give precise tasks and deadlines to employees to deliver products as required by industry standards and according to the company’s recipes). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q2 | In my company, there is unclear communication with employees on how to achieve product integrity (e.g., employees’ questions about product requirements, composition and recipes are often badly answered). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q3 | In my company, the importance of product integrity is recognized (e.g., leaders and employees’ main priority is to meet high product standards and fulfill customer requirements). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q4 | In my company, leaders and employees are aware of the hazards and threats related to product integrity (e.g., ingredients adulteration or contamination and product counterfeit or imitation are avoided). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q5 | In my company, the necessary resources are available to achieve product integrity (e.g., good selection of suppliers and raw materials, trained staff and sufficient time to work and perform controls are guaranteed). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| PROCESS INTEGRITY Process integrity means that a food product is produced using controlled and regular methods of production, where processes are well executed and assurance standards for food, packaging, hygiene, labor, animal and plant health are followed. | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Not agree nor disagree | Agree | Strongly agree | |

| Q6 | In my company, leaders have clear expectations on how to achieve process integrity (e.g., leaders require and trust employees to perform processes according to instructions and standard operating procedures). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q7 | In my company, there is clear communication with employees on how to achieve process integrity (e.g., employees understand well leaders’ explanations on how to execute and supervise all the steps of product processing). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q8 | In my company, leaders and employees act properly and constructively to solve issues that affect process integrity (e.g., leaders are prepared to face emergencies; employees are ready to correct incidents or non-compliances on the production line). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q9 | In my company, leaders and employees are aware of the hazards and threats related to process integrity (e.g., equipment, production line and processing methods are kept under control). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q10 | In my company, the necessary resources are not always available to achieve process integrity (e.g., equipment, replacement parts, workspaces and systems for production and process monitoring are not sufficient or inappropriate). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| PEOPLE INTEGRITY People integrity means that the people working in a company behave honestly and have ethical beliefs and attitudes (e.g., leaders and employees carefully respect rules and comply with high standards). | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Not agree nor disagree | Agree | Strongly agree | |

| Q11 | In my company, leaders aim to continuously improve people’ integrity (e.g., leaders motivate, involve and listen to employees’ concerns and suggestions, behave ethically and lead as role models). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q12 | In my company, the importance of people integrity and ethical behavior is communicated (e.g., employees are encouraged to discuss openly and honestly with leaders and colleagues). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q13 | In my company, working to improve people integrity by behaving ethically is not recognized or rewarded (e.g., incentives or positive feedback are not given to employees; dishonest behavior is often ignored or tolerated). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q14 | In my company, people integrity is fostered by being careful, alert and attentive to potential hazards and threats (e.g., employees care about each other’s well-being; leaders respect employees’ rights and take customers’ health seriously). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q15 | In my company, sufficient investments are made to improve people integrity (e.g., good working conditions, ethical code of conduct, conflict mediation service, employees’ training are offered; differences between people and diversity are respected). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| DATA INTEGRITY Data integrity means that all the information regarding a food product is true and accurate, including regular health certifications, valid import documents and correct product labeling, such as ingredient list, nutritional and technical specifications, origins and expiry dates. | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Not agree nor disagree | Agree | Strongly agree | |

| Q16 | In my company, leaders aim to continuously improve the level of data integrity (e.g., leaders always verify the quality of the data they receive from suppliers and make sure that food products are delivered as promised in the label and advertisements). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q17 | My company communicates badly on the importance of data integrity (e.g., employees receive insufficient written guidelines or receive unclear oral directions on how to prepare, verify and record precise product information). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q18 | In my company, leaders are committed to data integrity by setting a good example (e.g., leaders supervise and participate in work activities ensuring that labels match product properties and product information is recorded and provided correctly). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q19 | In my company, leaders and employees have a realistic picture of hazards and threats related to data integrity (e.g., false documents, invalid statistics or figures, irregular certificates and incorrect labeling are avoided). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q20 | In my company, sufficient investments are made to achieve data integrity (e.g., specific instructions and procedures, good tracking and tracing software, product registration databases and data recording programs are available). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| FOOD INTEGRITY COMPLIANCE | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Not agree nor disagree | Agree | Strongly agree | |

| Q21 | I always work with integrity and honesty. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q22 | I follow all prescribed and necessary standards, procedures, instructions and rules when I work (e.g., regarding hygiene, food safety, data, etc.). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q23 | I follow proper standards, procedures, instructions and rules when I perform my job (e.g., regarding hygiene, food safety, data, etc.). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q24 | I strive to perform my job according to the highest ethical standards. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q25 | I am able to work according to the ethical standards and values that the leaders in my company (e.g., my management) consider important. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| FOOD INTEGRITY PARTICIPATION | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Not agree nor disagree | Agree | Strongly agree | |

| Q26 | I promote honesty and I act as respectfully as possible within my organization, with care for the food products. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q27 | I am actively committed to the ethical functioning of my company. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q28 | I spontaneously support my colleagues if they are treated unfairly or not respectfully at work (e.g., employees help each other, stand up for each other and do not accept unfair behavior). | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q29 | I voluntarily perform additional tasks and activities within my company that benefit the safety and quality of the food produced. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q30 | I voluntarily perform additional tasks and activities within my organization that benefit the well-being or health of the employees in my company. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| UNETHICAL PRO-ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOR | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Not agree nor disagree | Agree | Strongly agree | |

| Q31 | I would be willing to misrepresent the truth to give my organization a positive image. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q32 | I would be willing to provide exaggerated information about my organization’s food products if it is important for my company. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q33 | I would be willing to provide negative information about my organization’s food products. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q34 | I would be willing to provide information about unfair practices in my organization that are hidden from the outside world. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| FOOD INTEGRITY KNOWLEDGE | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Not agree nor disagree | Agree | Strongly agree | |

| Q35 | I know how to carry out my work tasks with integrity and I can perform my job in a fair manner. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q36 | I am aware of the ethical standards, values and principles that are important to my organization. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q37 | I know what I can and cannot do in my organization. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q38 | I am aware of the risks in my job that can lead to unfair practices regarding the food produced. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q39 | I know how to reduce hygiene and food safety risks in my workplace. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q40 | I have the necessary knowledge to maintain and improve hygiene and food safety in my workplace. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| FOOD INTEGRITY MOTIVATION | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Not agree nor disagree | Agree | Strongly agree | |

| Q41 | I believe that integrity and honesty at work are very important. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q42 | I feel it is worth the effort to ensure, maintain and improve the safety and quality of the food produced. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q43 | Any efforts to promote the well-being and improve the health of employees are important for the quality and safety of the produced food. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q44 | I personally think it is very important to conduct a responsible, fair and authentic production of food products in my company. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q45 | I feel it is important to behave ethically at all times in my company. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q46 | I think it is important that everyone in my company adheres to the ethical standards and values that the leaders in my company (e.g., my management) consider important. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q47 | I think it is important to reduce at the minimum any risks that may lead to unfair practices regarding the food products produced in my company. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| BURNOUT AND JOB STRESSEmployees’ psychological well-being | Never | Hardly | Occasionally | Regularly | Often | Very often | Always | |

| Q49 | I feel mentally exhausted because of my job. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Q50 | I have become more cynical about the results of my work. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Q51 | I feel that with my work I make a positive contribution to the functioning of the organization. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Q52 | How often do you feel stressed because of your job? | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| CONSCIENTIOUSNESS | Strongly disagree | Disagree | Not agree nor disagree | Agree | Strongly agree | |

| Q53 | I am always well prepared. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q54 | When I make plans, I stick to them. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q55 | I pay attention to details. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q56 | I do not procrastinate, I perform my tasks right away. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Q57 | It is hard for me to keep things up for a long time. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

References

- EFSA. The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks in 2012. EFSA J. 2014, 12, 3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R. Food Fraud and “Economically Motivated Adulteration” of Food and Food Ingredients; Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; Available online: https://bit.ly/3u7ibsW (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Spink, J.; Ortega, D.L.; Chen, C.; Wu, F. Food fraud prevention shifts the food risk focus to vulnerability. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 62, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ruth, S.M.; Huisman, W.; Luning, P.A. Food fraud vulnerability and its key factors. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 67, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, L. Food fraud: Policy and food chain. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2016, 10, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.S.; Van Fleet, D.D.; Mishra, A.K. Food integrity: A market-based solution. Br. Food J. 2017, 119, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.H.; Suleiman, N. Eleven shades of food integrity: A halal supply chain perspective. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 71, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boeck, E.; Mortier, A.V.; Jacxsens, L.; Dequidt, L.; Vlerick, P. Towards an extended food safety culture model: Studying the moderating role of burnout and jobstress, the mediating role of food safety knowledge and motivation in the relation between food safety climate and food safety behavior. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 62, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrobaish, W.S.; Jacxsens, L.; Luning, P.A.; Vlerick, P. Food Integrity Climate in Food Businesses: Conceptualization, Development, and Validation of a Self-Assessment Tool. Foods 2021, 10, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, A.; Griffin, M.A. Safety climate and safety at work. In The Psychology of Workplace Safety; Barling, J., Frone, M.R., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; pp. 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyen, B.; Vlerick, P.; Soenens, G.; Vermassen, F.; Van Herzeele, I. Team perception of the radiation safety climate in the hybrid angiography suite: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 77, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.M. Ethical Decision Making by Individuals in Organizations: An Issue-Contingent Mode. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 366–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umphress, E.E.; Bingham, J.B. When employees do bad things for good reasons: Examining unethical pro-organizational behaviors. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 621–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denison, D.R. What is the Difference Between Organizational Culture and Organizational Climate? A Native’s Point of View on a Decade of Paradigm Wars. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 619–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptein, M. Toward Effective Codes: Testing the Relationship with Unethical Behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 99, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, R.R.; Brinkmann, J. Leaders as moral role models: The case of John Gutreund at Salomon Brothers. J. Bus. Ethics 2002, 35, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zopiatis, A.; Orphanides, N. Investigating occupational burnout of food and beverage employees. Br. Food J. 2009, 111, 930–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. Developments in Working Life in Europe 2015: EurWork Annual Review; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; Available online: https://bit.ly/3uTJ7vr (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Tennant, C. Work-related stress and depressive disorders. J. Psychosom. Res. 2001, 51, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasurdin, A.; Ramayah, T.; Chee Beng, Y. Organizational structure and organizational climate as potential predictors of job stress: Evidence from Malaysia. Int. J. Commer. Manag. 2006, 16, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegrist, J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1996, 1, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beehr, T.A. Perceived situational moderators of the relationship between subjective role ambiguity and role strain. J. Appl. Psychol. 1976, 61, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, R.L.; Byosiere, P. Stress in organizations. In Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Consulting Psychologists Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1992; pp. 571–650. Available online: https://bit.ly/3DKASWl (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- Le Blanc, P.M.; De Jonge, J.; Schaufeli, W.B. Job stress and occupational health. In An Introduction to Work and Organizational Psychology: A European Perspective, 2nd ed.; Chmiel, N., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 148–177. [Google Scholar]

- Schabracq, M.J.; Cooper, C.L. The changing nature of work and stress. J. Manag. Psychol. 2000, 15, 227–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, M.A.; Dollard, M.F. Psychosocial safety climate, work conditions, and emotions in the workplace: A Malaysian population-based work stress study. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2011, 18, 324–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelfrene, E.; Vlerick, P.; Moreau, M.; Mak, R.; Kornitzer, M.; De Backer, G. Use of benzodiazepine drugs and perceived job stress in a cohort of working men and women in Belgium. Results from the BELSTRESS-study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 59, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, K.; Hong, W. The Effect of Food Sustainability and the Food Safety Climate on the Job Stress, Job Satisfaction and Job Commitment of Kitchen Staff. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, F.F.T.; Birtch, T.A.; Kwan, H.K. The moderating roles of job control and work-life balance practices on employee stress in the hotel and catering industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E. The measurement of experienced burnout. J. Organ. Behav. 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Leiter, M.P. Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetland, H.; Sandal, G.M.; Johnsen, T.B. Followers’ personality and leadership. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2008, 14, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.T.; Hakim, M.P.; Zanetta, L.D.; Pinheiro, G.S.D.D.; Gemma, S.F.B.; Da Cunha, D.T. Burnout and food safety: Understanding the role of job satisfaction and menu complexity in foodservice. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.A.; Neal, A. Perceptions of safety at work: A framework for linking safety climate to safety performance, knowledge, and motivation. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2000, 5, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boeck, E.; Jacxsens, L.; Bollaerts, M.; Vlerick, P. Food safety climate in food processing organizations: Development and validation of a self-assessment tool. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 46, 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weijters, B.; Baumgartner, H. Misresponse to Reversed and Negated Items in Surveys: A Review. J. Mark. Res. 2012, 49, 737–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, M.R.; Mohr, D.C.; Waddimba, A.C. The reliability and validity of three-item screening measures for burnout: Evidence from group-employed health care practitioners in upstate New York. Stress Health 2018, 34, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, O.P.; Srivastava, S. The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research, 2nd ed.; Pervin, L., John, O.P., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ones, D.; Viswesvaran, C.; Schmidt, F. Comprehensive meta-analysis of integrity test validities: Findings and implications for personnel selection and theories of job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 679–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPIP. A Scientific Collaboratory for the Development of Advanced Measures of Personality Traits and Other Individual Differences. 2001. Available online: https://ipip.ori.org (accessed on 6 April 2022).

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maneesriwongul, W.; Dixon, J.K. Instrument translation process: A methods review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004, 48, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leontitsis, A.; Pagge, J. A simulation approach on Cronbach’s alpha statistical significance. Math. Comput. Simul. 2007, 73, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator mediator variable distinction in social psychological research-conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panisello, P.J.; Quantick, P.C. Technical barriers to hazard analysis critical control point (HACCP). Food Control 2001, 12, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yapp, C.; Fairman, R. Factors affecting food safety compliance within small and medium-sized enterprises: Implications for regulatory and enforcement strategies. Food Control 2006, 17, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, N. Chapter 13. Job satisfaction, motivation and performance. In An Introduction to Contemporary Work Psychology; Peeters, M., De Jonge, J., Taris, T., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pignata, S.; Biron, C.; Dollard, M. Chapter 16. Managing psychosocial risks in the workplace: Prevention and intervention. In An Introduction to Contemporary Work Psychology; Peeters, M., de Jonge, J., Taris, T., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tetrick, L.E.; Winslow, C.J. Workplace Stress Management Interventions and Health Promotion. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 583–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.S. Effects of supply chain management practices, integration and competition capability on performance. Supply Chain Manag. 2006, 11, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinodkumar, M.; Bhasi, M. Safety management practices and safety behaviour: Assessing the mediating role of safety knowledge and motivation. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2010, 42, 2082–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatimah, U.; Strohbehn, C.H.; Arendt, S.W. An empirical investigation of food safety culture in onsite foodservice operations. Food Control 2014, 46, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, S.W.; Strohbehn, C.H.; Meyer, J.; Paez, P. Development and use of an instrument to measure retail foodservice employees motivation for following food safety practices. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2011, 14, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, M.; Tian, A.W.; Soo, C.; Zhang, B.; Ho, K.S.B.; Hosszu, K. Different motivations for knowledge sharing and hiding: The role of motivating work design. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 783–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neal, J.A.; Binkley, M.; Henroid, D. Assessing Factors Contributing to Food Safety Culture in Retail Food Establishments. Food Prot. Trends 2012, 32, 468–476. [Google Scholar]

- Kleboth, J.; Luning, P.; Fogliano, V. Risk-based integrity audits in the food chain: A framework for complex systems. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 56, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhry, R.; Fang, D.; Lingard, H. Measuring Safety Climate of a Construction Company. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2009, 135, 890–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, L. Moving from a compliance-based to an integrity-based organizational climate in the food supply chain. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 995–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgwick, P. Cross sectional studies: Advantages and disadvantages. BMJ 2014, 348, g2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levin, K.A. Study design III: Cross-sectional studies. Evid.-Based Dent. 2006, 7, 24–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.P.; Nathan, P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spector, P.E. Method Variance in Organizational Research: Truth or Urban Legend? Organ. Res. Methods 2006, 9, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luning, P.A.; Marcelis, W.J.; Rovira, J.; Van Boekel, M.A.J.S.; Uyttendaele, M.; Jacxsens, L. A tool to diagnose context riskiness in view of food safety activities and microbiological safety output. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 22, S67–S79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitropoulos, P.; Memarian, B. Team processes and safety of Workers: Cognitive, affective, and behavioral processes of construction crews. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2012, 138, 1181–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyarugwe, S.P.; Linnemann, A.; Hofstede, G.J.; Fogliano, V.; Luning, P.A. Determinants for conducting food safety culture research. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2016, 56, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Percentage | Mean | Standard Deviation | F-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company | 5.76 ** | |||

| A | 11.9 | 63.23 | 5.51 | |

| B | 28 | 55.28 | 7.47 | |

| C | 29.7 | 58.22 | 5.96 | |

| D | 30.5 | 59.66 | 5.06 | |

| Age | 1.23 | |||

| <26 years old | 8.5 | 57.10 | 3.99 | |

| Between 26–30 years old | 11.9 | 56.21 | 5.86 | |

| Between 31–40 years old | 18.6 | 60.63 | 5.74 | |

| Between 41–50 years old | 28.8 | 59.39 | 7.11 | |

| Between 51–60 years old | 24.6 | 57.30 | 7.44 | |

| >60 years old | 7.6 | 59.75 | 4.59 | |

| Seniority | 0.95 | |||

| <1 year | 7.6 | 59.86 | 8.40 | |

| Between 1–5 years | 27.1 | 58.10 | 6.21 | |

| Between 6–10 years | 14.4 | 59.88 | 6.38 | |

| Between 11–15 years | 17.8 | 59.58 | 8.32 | |

| Between 16–20 years | 8.5 | 54.90 | 6.23 | |

| >20 years | 24.6 | 58.32 | 4.83 | |

| Function | 1.61 | |||

| Management | 10.2 | 61.50 | 6.43 | |

| Daily contact with food | 67.8 | 57.92 | 6.65 | |

| No direct contact with food | 22 | 58.72 | 5.83 | |

| Contract | 0.16 | |||

| Permanent contract | 85.1 | 58.43 | 6.29 | |

| Temporary contract | 14.9 | 59.38 | 9.09 | |

| Conscientiousness | 7.40 *** |

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Conscientiousness | 20.23/25 | 2.58 | (0.67) | ||||||

| 2. Food Integrity Climate | 78.08/100 | 10.64 | 0.35 ** | (0.91) | |||||

| 3. Burnout | 8.06/21 | 3.70 | −0.31 ** | −0.44 ** | (0.62) | ||||

| 4. Job stress | 3.37/7 | 1.65 | −0.05 | −0.32 ** | 0.49 ** | - | |||

| 5. Knowledge | 25.55/30 | 3.04 | 0.58 ** | 0.40 ** | −0.36 ** | −0.03 | (0.82) | ||

| 6. Motivation | 30.59/35 | 3.37 | 0.56 ** | 0.58 ** | −0.37 ** | −0.08 | 0.72 ** | (0.83) | |

| 7. Food Integrity Behavior | 58.50/70 | 6.48 | 0.55 ** | 0.54 ** | −0.42 ** | −0.04 | 0.64 ** | 0.71 ** | (0.84) |

| Predictor | Food Integrity Behavior | Compliance | Participation | Unethical Behavior | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| 1. Control Variables | ||||||||

| Company | ||||||||

| B | −0.39 ** | −0.31 ** | −0.32 * | −0.21 | −0.42 ** | −0.35 ** | −0.15 | −0.10 |

| C | −0.32 ** | −0.24 * | −0.25 * | −0.14 | −0.47 *** | −0.40 * | −0.07 | −0.03 |

| D | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.14 | −0.12 | −0.26 * | −0.26 * | 0.17 | 0.18 |

| Conscientiousness | 0.57 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.54 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.48 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.34 *** | 0.27 ** |

| 2. Food Integrity Climate | 0.31 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.25 ** | 0.18 | ||||

| R2 | 0.43 *** | 0.51 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.48 *** | 0.34 *** | 0.39 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.19 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.41 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.34 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.36 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.15 |

| ΔR2 | 0.43 *** | 0.08 *** | 0.36 *** | 0.12 *** | 0.34 *** | 0.05 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.03 |

| Predictor | Food Integrity Behavior | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| 1. Control Variables | |||

| Company | |||

| B | −0.39 ** | −0.31 ** | −0.31 ** |

| C | −0.32 ** | −0.20 | −0.22 |

| D | −0.05 | −0.02 | −0.02 |

| Conscientiousness | 0.57 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.43 *** |

| 2. Food Integrity Climate | 0.36 *** | 0.38 *** | |

| Job stress | 0.14 | 0.12 | |

| 3. Food Integrity Climate × Job stress | −0.13 | ||

| R2 | 0.43 *** | 0.53 *** | 0.54 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.41 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.51 |

| ΔR2 | 0.43 *** | 0.10 *** | 0.02 |

| Predictor | Food Integrity Behavior | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| 1. Control Variables | |||

| Company | |||

| B | −0.39 ** | −0.29 * | −0.27 * |

| C | −0.32 * | −0.26 * | −0.25 * |

| D | −0.05 | −0.07 | −0.07 |

| Conscientiousness | 0.57 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.44 *** |

| 2. Food Integrity Climate | 0.27 ** | 0.28 ** | |

| Burnout | −0.13 | −0.11 | |

| 3. Food Integrity Climate × Burnout | 0.06 | ||

| R2 | 0.42 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.52 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.40 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.49 |

| ΔR2 | 0.43 *** | 0.10 *** | 0 |

| Predictor | Food Integrity Knowledge | Food Integrity Motivation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

| 1. Control Variables | ||||

| Company | ||||

| B | −0.33 * | −0.27 * | −0.34 * | −0.27 * |

| C | −0.30 * | −0.25 * | −0.30 * | −0.18 |

| D | −0.27 * | −0.27 * | −0.17 | −0.15 |

| Conscientiousness | 0.55 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.55 ** | 0.40 ** |

| 2. Food Integrity Climate | 0.20 * | 0.39 ** | ||

| R2 | 0.38 ** | 0.41 * | 0.37 ** | 0.49 ** |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.36 ** | 0.39 * | 0.35 ** | 0.47 ** |

| ΔR2 | 0.38 ** | 0.03 * | 0.37 ** | 0.12 ** |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alrobaish, W.S.; Vlerick, P.; Steuperaert, N.; Jacxsens, L. An Exploratory Study on the Relation between Companies’ Food Integrity Climate and Employees’ Food Integrity Behavior in Food Businesses. Foods 2022, 11, 2657. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11172657

Alrobaish WS, Vlerick P, Steuperaert N, Jacxsens L. An Exploratory Study on the Relation between Companies’ Food Integrity Climate and Employees’ Food Integrity Behavior in Food Businesses. Foods. 2022; 11(17):2657. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11172657

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlrobaish, Waeel Salih, Peter Vlerick, Noëmie Steuperaert, and Liesbeth Jacxsens. 2022. "An Exploratory Study on the Relation between Companies’ Food Integrity Climate and Employees’ Food Integrity Behavior in Food Businesses" Foods 11, no. 17: 2657. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11172657

APA StyleAlrobaish, W. S., Vlerick, P., Steuperaert, N., & Jacxsens, L. (2022). An Exploratory Study on the Relation between Companies’ Food Integrity Climate and Employees’ Food Integrity Behavior in Food Businesses. Foods, 11(17), 2657. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11172657