The Role of Local Seasonal Foods in Enhancing Sustainable Food Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

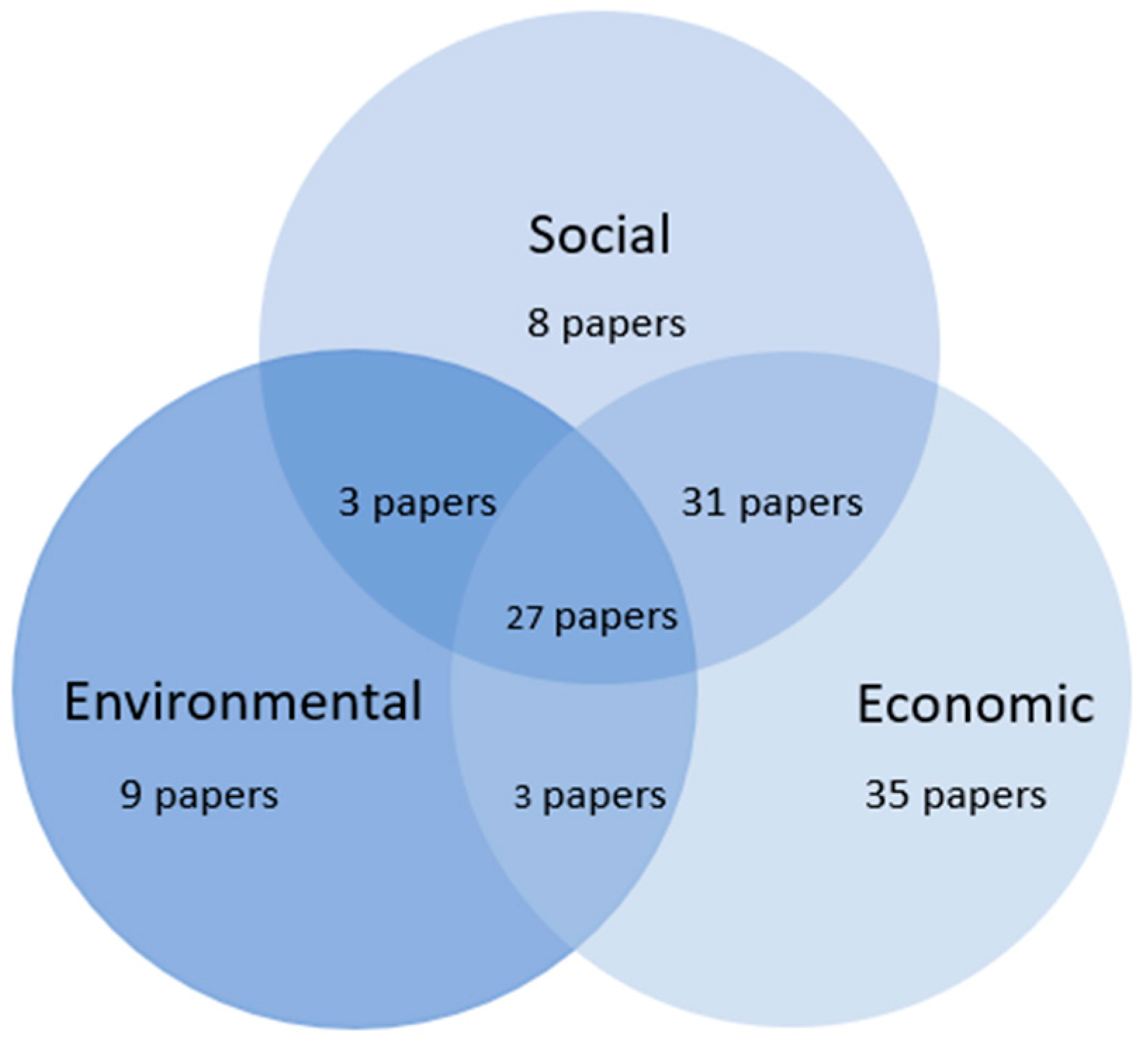

3.1. Overview of Identified Studies

3.2. Seasonal Food

3.3. Local Food

4. Discussion on Sustainability of Local Seasonal Food

4.1. Economic and Social Dimensions

4.2. Environment Dimension

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author and Year of Publication | Aim | Sustainable Dimensions | Methodology | Address or Reference Seasonality | Scope | Sample | Identified concept of Seasonality * | Identified concept of Local Food ** | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wilkins, 1996 | To explore the relationship between a preference for local foods and other dietary patterns. | Social, Economic, and Environment | Mailed survey | Yes | Seasonal and Local Food | N = 309 Puget Consumers’ Cooperative (PCC) members (n = 193) and a random selection of Washington State (US) residents (n = 116) | IS | G | [32] |

| Wilkins et al., 2002 | To explore how consumers conceptualize “local” and “seasonal” as applied to foods. | Social, Economic and Environment | Face-to-face survey open-ended questions about the meanings of local and seasonal foods | Yes | Seasonal and Local Food | N = 120 Shoppers in a grocery store and a food cooperative | IS | G, R | [25] |

| Morris and Buller, 2003 | To investigate the range and scope of local food production in the county of Gloucestershire and consider the potential of local food production and marketing for adding value for the various actors in the chain. | Economic | Case Study and face-to-face interviews | No | Local Food | N = 23 Farmers (n = 15); retailers (n = 8) | N.A. | R | [132] |

| Zepeda and Leviten-Reid, 2004 | To investigate consumers’ interests, attitudes, and motivations for buying local food. | Economic and Environment | Focus Group | No | Local Food | N = 41 Alternative food shoppers (n = 22); Conventional consumers (n = 21) | N.A. | G | [58] |

| Roininen et al., 2005 | To establish the personal values, meanings, and specific benefits consumers relate to local food products. | Social and Economic | Word association and laddering interviews | No | Local Food | N = 55 Consumers | N.A. | H | [103] |

| Selfa and Qazi, 2005 | To exam how consumers and producers conceptualize local. | Social and Economic | Case Study and online survey | Yes | Local Food | Food Chain Key Informants | IS | G | [33] |

| Born and Purcell, 2006 | To theorize geographical scale that entirely precludes the local trap. | Social, Economic, and Environment | Theoretical approach to scale local trap | No | Local Food | Theoretical approach | N.A. | H | [104] |

| Sirieix et al., 2008 | To identify whether food miles matter to French consumers. | Social, Economic, and Environment | Focus groups and face-to-face interviews | No | Food Miles | N = 26 Random consumers (n = 16) for a focus group; consumers of locally grown organic food consumers for survey (n = 10) | N.A. | G | [59] |

| Weber and Mattews, 2008 | To compare the life-cycle greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions associated with food production against long-distance distribution. | Environment | Life Cycle Assessment | No | Food Miles | N.A. | N.A. | G | [60] |

| Coley et al., 2009 | To discuss the conception of food miles, followed by an empirical application of food miles to two contrasting food distribution systems based on carbon emissions accounting within these systems. | Environment | Data analysis of fuel and energy use from one UK’s supplier of organic produce | No | Food Miles | N.A. | N.A. | G | [61] |

| Cross et al., 2009 | To compare the self-reported health of farm workers who were producing the same product in four different countries with relevant population norms. | Social | Health-related quality of life approach using survey instrument adapted from SF-36, EuroQuol EQ-5D, and Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) | No | Worker Health in local and global food systems | N = 2545 food systems workers | N.A. | G | [62] |

| Nousiainen et al., 2009 | To examine factors that contribute to the social sustainability of AFS, by focusing on local and organic food system initiatives in Juva, Finland. | Social | Case study and face-to-face interviews | No | Alternative Food Networks | N = 20 AFN stakeholders | N.A. | G, H | [63] |

| Zepeda and Deal, 2009 | To increase understanding of why consumers buy organic and/or local foods. | Economic | Face-to-face interviews | No | Local Food | N = 25 Consumers | N.A. | G | [64] |

| Arnoult et al., 2010 | To estimate willingness to pay for foods of a designated origin, together with certification for organic and free of genetically modified (GM) ingredients. | Economic | Focus groups and face-to-face interviews; choice experiment | Yes | Seasonal Food | N = 222 Consumers | IS | G | [34] |

| Conner et al., 2010 | To identify opportunities and obstacles which inform marketing strategies for local food and farmers markets and reflect the demographic diversity of the state. | Economic | Telephone survey | No | Local Food | N = 953 Consumers | N.A. | G | [65] |

| Louden and MacRae, 2010 | To examine whether current federal labeling rules might impede the marketing of local and sustainable claims. | Economic | Case study; data analysis on current local and sustainable food labeling regulation and application | No | Value-added labels | N.A. | N.A. | G | [66] |

| Milestad et al., 2010 | To explore the social relations between food actors and how “local” and “organic” are expressed by detailing how actors describe qualities of their intra-network relationships, how they understand “local”, and how they are connected within the food system. | Social and Economic | Face-to-face interviews and workshops | Yes | Local Food | N = 15 Food Chain Key Informants | IS | H | [35] |

| Bean and Sharp, 2011 | To examine how two possible consumptive pathways, the purchase of organic foods and/or the purchase of local foods, can affect food sustainability. | Economic | Mailed survey | No | Local and Organic Food | N = 2398 Consumers | N.A. | G | [67] |

| Brooks et al., 2011 | To summarizes research by Defra, which studied consumers’ understanding of, and attitudes to, seasonal foods, and the environmental implications of applying certain “seasonal” definitions to guide food sourcing. | Social, Economic, and Environment | Focus groups, online quantitative survey, and Life Cycle Assessment | Yes | Seasonal Food | N= 1200 Grocery buyers | PS, LS | G | [17] |

| Levidow and Psarikidou, 2011 | To explore agro-food relocalization initiative | Economic and Environment | Case study and face-to-face interviews | No | Local Food | N = 12 Local food chain stakeholders | N.A. | H | [105] |

| Pearson et al., 2011 | To analyze of consumers of a local food retail outlet in the UK that is based on weekly community markets. | Social, Economic, and Environment | Case study; face-to-face survey | Yes | Local Food | N = 183 Consumers | LS | H | [45] |

| Wirth et al., 2011 | To determine the relative strength of two credence attributes, organic and locally produced, within the context of fresh apple. | Economic | Focus groups and online survey; conjoint analysis | No | Local and Organic Food | N = 1218 Consumers | N.A. | G | [68] |

| Hayden and Buck, 2012 | To identify whether and how CSA membership affects environmental ethics. | Economic | Online survey and face-to-face interviews | No | CSA | N = 48 CSA members | N.A. | H | [106] |

| Hu et al., 2012 | To estimate consumer willingness to pay for varieties of a processed food product that are differentiated with respect to their local production labelling and a series of other value-added claims. | Social and Economic | Mailed survey; conjoint analysis | No | Value-added labels | N= 1884 Consumers | N.A. | G | [69] |

| Rainbolt et al., 2012 | To identify factors that might influence consumer valuation of organic, fair trade, and local labeled food. | Economic | Online survey | No | Local Food | N = 1269 Consumers | N.A. | G | [70] |

| Uribe et al., 2012 | To examine whether ecological attitudes of CSA members could predict food and sustainability related behaviors. | Social and Environment | Online survey | Yes | CSA | N = 115 CSA members | IS | H | [36] |

| Amate and González De Molina, 2013 | To evaluate the energy cost of the Spanish agri-food (AFS) system in the year 2000 with a view to ascertaining the relative importance of each link in the agri-food chain. | Environment | Life Cycle Assessment | Yes | Agroecological Food System | N = 1 Country (Spain) | LS | G | [46] |

| Aubry and Kebir, 2013 | To investigate the role of SSFCs in a potential revival of the food supply function of agriculture located close to cities. | Social and Economic | Face-to-face interview | No | Short Food Supply Chains | N = 68 Short supply food chains stakeholders; consumers (n = 90); farmers (n = 60); Decision-makers (n = 8) | N.A. | H | [107] |

| Fonte, 2013 | To examine the discourses and practices of GAS (Gruppi di Acquisto Solidali) operating in Rome (Italy). | Social, Economic and Environment | Face-to-face interviews | No | Solidarity Purchasing Groups | N = 28 Solidarity Purchasing Groups Representatives | N.A. | H | [108] |

| Long and Murray, 2013 | To explores convergence and divergence of ethical consumption values through a study of organic, fair trade, and local food consumers in Colorado | Economic | Mailed survey and focus groups | No | Ethical consumption | N = 469 Consumers | N.A. | H | [109] |

| Pratt, 2013 | To analyses a small island ecotourism project in Fiji in the context of food miles and sustainability. | Social and Economic | Online survey | Yes | Food Miles | N = 205 Consumers | LS | G | [47] |

| Röös and Karlsson, 2013 | To investigate how the carbon footprint of yearly per capita consumption of tomatoes and carrots in Sweden was affected by seasonal consumption according to interpretations of seasonality found in communications from Swedish NGOs and authorities. | Environment | Data analysis of carbon footprint of yearly per capita consumption of tomatoes and carrots in Sweden was affected by seasonal consumption according to interpretations of seasonality | Yes | Seasonal Food and Carbon Footprint | N.A. | IS, PS, LS | G | [30] |

| Schnell, 2013 | To explore the ongoing debates over food miles and local food. | Social, Economic and Environment | Face-to-face interviews | Yes | Food Miles and CSAs | N = 30 CSA members | IS | H | [37] |

| Sneyd, 2013 | To analyze wild food consumption in urban areas of Cameroon. | Social and Economic | Face-to-face interviews | Yes | Wild Food | N = 371 household and market’s consumers | IS | G | [38] |

| Wang et al., 2013 | To identify the patterns of main meal preparation among Australian adult household meal preparers and the relationships between these patterns and likely socio-demographic and psychological predictors. | Economic | Online survey | Yes | Patterns of main meal preparation | N = 222 Consumers | IS | - | [31] |

| Echeverría et al., 2013 | To elicit the WTP of Chilean consumers towards the carbon footprint of food products, controlling for several consumer’s attributes. | Economic and Environment | Contingent valuation; double bounded dichotomous choice survey | No | Carbon footprint on foods | N = 774 Supermarket consumers | N.A. | G | [71] |

| Foster et al., 2013 | To explore the environmental implications of upstream changes that arise as supply of particular foodstuffs progresses through the year. | Environment | Life Cycle Assessment | Yes | Seasonal Food | Data analysis | PS, LS | G | [19] |

| Knutson et al., 2014 | To analyze the public role of trade of U.S. fresh fruit and vegetable demand. | Economic | Data analysis of prices and quantities for fruits and fresh vegetables in USA from 1970 to 2011; vector autoregression | Yes | Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Demand | N = 1 Country (United States of America) | PS | [44] | |

| Lillywhite and Simonsen, 2014 | To evaluate consumers’ locally produced ingredient preferences relative to the price of the dining experience and restaurant type. | Social and Economic | Online survey; conjoint analysis | No | Local Food | N = 320 Consumers | N.A. | G | [72] |

| Cleveland et al., 2015 | To analyze the origin and effects of the focus on spatial scale and build on this analysis by operationalizing the concept of “local” food. | Social, Economic, and Environment | Case study; data analysis of public comments associated with reducing food miles as an action for and indicator of alternative food systems | No | Local Food | N = 496 comments | N.A. | G, H | [73] |

| Dedeurwaerdere et al., 2015 | To analyze the governance features of local food buying groups by comparing 104 groups in five cities in Belgium. | Economic | Face-to-face interviews | No | Local Food | N = 104 Collective Food Buying Groups Members | N.A. | H | [115] |

| Favilli et al., 2015 | To analyze the innovation potential of a local food network. | Social | Case Study; action research and participatory approach; workshops and face-to-face interviews | No | Organic Food | N = 20 Organic Food Systems stakeholders | N.A. | H | [116] |

| Memery et al., 2015 | To investigate how attributes associated with local food (intrinsic product quality; local support) motivate purchase behavior. | Economic | Online survey | No | Local Food | N = 1223 Consumers | N.A. | H | [117] |

| Aprile et al., 2016 | To examine consumers’ perception, attitude, and motivations for buying local foods and identify profiles of local foods’ consumers. | Economic | Face-to-face survey | No | Local Food | N = 200 Consumers | N.A. | G, H | [74] |

| Balázs et al., 2016 | To examine how farmer led CSA movement in Hungary creates an alternative in the dominant food regime. | Social and Economic | Face-to-face semi-structured interviews; a consumer-member survey and secondary data sources were utilized; the data analysis used thematic coding. | Yes | CSA | N = 91 Producers (N = 5); Policy makers and experts (n = 3); CSA Members (n = 83) | IS | H | [39] |

| De Boer et al., 2016 | To explore how the transition to a low-carbon society to mitigate climate change can be better supported by a diet change. | Social, Economic, and Environment | Online survey; profile analysis was used to assess how the participants evaluated the mitigation options. | Yes | Carbon Footprint | N = 1083 Consumers from the Netherlands (n = 527) and the United States (n = 556) | LS | G | [26] |

| Chiffoleau et al., 2016 | To explore the conditions under which local food chains in urban food systems can bring about an evolution in the practices and knowledge of “ordinary” actors with no or limited skills in agriculture and/or awareness of sustainability. | Social, Economic, and Environment | Case Study; face-to-face interviews | Yes | Short Food Supply Chain | N = 60 Retailers (n = 30); Consumers (n = 30) | LS | H | [48] |

| Darolt et al., 2016 | To show that alternative food networks produce social innovation, diversity, and new values that can contribute to reconnect producers and consumers, aggregate value to local markets through short distribution channels. | Social, Economic, and Environment | Face-to-face interviews | Yes | Alternative Food Networks | N = 20 Food Chain Key Informants | LS | H | [49] |

| Hvitsand, 2016 | To identify why Norwegian producers and consumers engage in CSA and how CSA can be seen as a transformational act toward food system changes. | Social, Economic, and Environment | Face-to-face interviews with farmers; online survey with CSA members | Yes | CSA | N = 456 Farmers (n = 7); Consumers (n = 449) | LS | H | [50] |

| Merle et al., 2016 | To examine the impact of a local origin label on perceptions and purchase intent regarding food products. | Social, Economic, and Environment | Online survey | Yes | Indication of Local Geographic Origin | N = 509 Consumers | LS | G, H, R | [51] |

| Mundler and Laughrea, 2016 | To evaluate the contributions of SFSCs to territorial development in three contrasting Quebec territories. | Social, Economic, and Environment | Case Study; online survey | No | Short Food Supply Chains | N = 97 Short supply food chains stakeholders | N.A. | H | [110] |

| O’Kane, 2016 | To examine the individual, social, physical, and macro-level environments that can positively or negatively influence peoples’ engagement with food citizenship. | Social and Economic | Focus groups; narrative inquiry | Yes | Food Citizenship | N = 52 Community gardeners (n = 6); regular farmers’ market shoppers (n = 10); CSA members (n = 4); fresh food market (n = 8); and supermarket shoppers (n = 24) | IS | H | [14] |

| Schmitt et al., 2016 | To compare the multi-dimensional performance of a local with a global food chain. | Social, Economic, and Environment | Selection of a set of attributes and indicators of performance to compare the multidimensional performance of a local with a global food chain; face-to-face interviews | No | Local and Global milk chain | N = 10 Local milk stakeholders (n = 6); Global milk stakeholders (n = 4) | N.A. | G, R | [75] |

| Touzard et al., 2016 | To objectivize which aspects of wine are local, and which are global, using a multidimensional analytical approach. | Social, Economic, and Environment | Case study; analytical and participatory approach; focus groups and face-to-face interviews | No | Local and Global wine | N = 24 Local wine chain stakeholders | N.A. | G, R | [76] |

| Bakos et al., 2017 | To present an overview of the development and current state of CSAs systems on the international and Hungarian level. | Social and Economic | Face-to-face survey | Yes | CSA | N = 817 | IS | H | [40] |

| Bellante, 2017 | To explore innovative strategies and limitations of AFNs. | Social and Economic | Case study and face-to-face interviews | No | Alternative Food Networks | N = 51 Local Food Systems stakeholders | N.A. | H | [111] |

| Berg and Preston, 2017 | To address the question of which observable factors about consumers are relatively important in influencing expenditures, shopping frequencies, and willingness to pay (WTP) premiums for local food. | Economic | Face-to-face interviews | No | Local Food | N = 237 Farm Market Consumers | N.A. | G | [77] |

| Bianchi, 2017 | To examine the drivers of local food purchase intentions for Chilean consumers | Economic | Online survey | No | Local Food | N = 1000 Consumers | N.A. | G, H | [78] |

| Granvik et al., 2017 | To contribute to knowledge on definitions, interpretations, and practices of local food by presenting views and opinions among different actors in the food chain in a Swedish context. | Social and Economic | Online survey | No | Local Food | N= 158 Local Food Systems stakeholders from: Sweden (n = 97); Austria (n = 2); Great Britain (n = 23); Denmark (n = 1); Finland (n = 1); Italy (n = 3); Norway (n = 1); Spain (n = 1); The Netherlands (n = 6); and USA (n = 22) | N.A. | G, H, R | [79] |

| Lurie and Brekken, 2017 | To analyze the contribution of small-scale agriculture in rural Oregon to the framework. | Economic | Online survey | No | New natural resource economy | N = 642 Farmers (n = 153); Consumers (n = 489) | N.A. | H | [112] |

| Lutz et al., 2017 | To illustrate various forms of cooperation in relation to small-scale farming and the establishment of local food supply. | Social and Economic | Case study; Social Multi-Criteria Evaluation and workshops | No | Local Food | N = 6 Farmers | N.A. | H | [113] |

| Russel and Zepeda, 2017 | To examine attitude and behavior change associated with CSA membership. | Social and Economic | Focus groups | No | CSA | N = 23 CSA members | N.A. | H | [114] |

| Schmutz et al., 2017 | To build a more detailed understanding of different types of urban SFSC and their relative performance compared to each other. | Social and Economic | Case study; sustainability impact assessment; workshop and face-to-face interviews | No | Short Food Supply Chains | N = 86 Short supply food chains stakeholders | N.A. | H | [119] |

| Schoolman, 2017 | To explore whether growth in local food systems is associated with decreased on-farm use of agricultural chemicals. | Environment | Longitudinal data analysis from the US Census of Agriculture to explore whether growth in local food systems is associated with decreased on-farm use of agricultural chemicals. | No | Local food | N.A. | N.A. | G | [80] |

| Telligman et al., 2017 | To investigate U.S. consumers’ perceptions of local beef, including the definitions and types of quality perceptions held for local beef products. | Social, Economic, and Environment | Face-to-face interviews | No | Local beef | N = 174 Beef consumers | N.A. | G, H | [81] |

| Tichenor et al., 2017 | To quantify the environmental burdens of grass-fed beef with management-intensive grazing and confinement dairy beef production systems in the northeastern U.S. | Environment | Life cycle assessment | No | Beef production systems | N.A. | N.A. | G | [82] |

| White and Bunn, 2017 | To identify a series of emergent policy pathways for UA practice and demonstrate that local government can assume a diverse leadership role as a promoter, enabler, and manager of UA. | Social and Environment | Case study; participant observation; focus groups and face-to-face interviews. | No | Urban agriculture | N = 30 Urban Agriculture actors | N.A. | H | [118] |

| De Chabert-Rios et al., 2018 | To understand the reasons why some restaurateurs are entering the farming business, and to learn about the financial, operational, and customer-related benefits and challenges encountered by restaurateurs operating their own farms. | Economic | Case study and face-to-face interviews | Yes | Local Food | N = 3 Restaurants | LS | G | [27] |

| Crawford et al., 2018 | To understand the socio-demographic characteristics and motivations, concerns, and attitudes of shoppers attending farmers’ markets in Sydney. | Social | Face-to-face survey | Yes | Local Food | N = 633 Farmers’ Markets Consumers | LS | G | [28] |

| Furman and Papavasiliou, 2018 | To examine how a food hub with close ties to the local food movement in Atlanta, Georgia contends with this issue as it articulates with larger markets. | Social and Economic | Case study; participatory action research; face-to-face interviews | No | Food Hubs | N = 34 Food hub managers (n = 5); farmers (n = 21); chefs (n = 8) | N.A. | H | [120] |

| Hashem et al., 2018 | To explain the growing interest of English consumers in local organic food sold through box schemes. | Social, Economic, and Environment | Face-to-face interviews; online survey | No | Local and Organic Box Schemes | N = 438 Box scheme consumers | N.A. | H | [122] |

| Kulick, 2018 | To explore how one statewide food network in the United States seeks to involve youth contending with the juvenile justice system in a job readiness program. | Social | Case study; participatory action research; face-to-face interview | No | Alternative Food Networks | N = 24 Stakeholders in the local food (n = 7) and juvenile justice system (n = 17) | N.A. | H | [99] |

| McKay et al., 2018 | To examine restaurant WTP for local products. | Economic | Telephone survey; contingent valuation | No | Local Food | N = 152 Restaurants | N.A. | G | [83] |

| Pícha et al., 2018 | To test the parameters that influenced preferences among food products branded as national, regional, or local products. | Social and Economic | Face-to-face survey | No | Local Food | N = 988 Consumers | N.A. | G, H, R | [90] |

| Scalvedi and Saba, 2018 | To identify sustainability aspects that overlap with local and organic consumer profiles in order to provide evidence that can be used to promote both kinds of foods in a sustainable food consumption (SFC) integrated framework. | Social and Economic | Face-to-face survey | Yes | Local and Organic Food | N = 3004 Consumers | N.A. | G, H | [21] |

| Schmitt et al., 2018 | To address the lack of metrics for quantifying the degree of localness of a food value chain (FVC) using a multi-criteria evaluation. | Social, Economic, and Environment | Case study and face-to-face interviews | No | Local Food | N = 97 Local (n = 11) and global (n = 86) cheese chain stakeholders | N.A. | G, H, R | [54] |

| Skog et al., 2018 | To investigate how adaptive governance of LFS can provide ideas and act as a catalyst for creating resilience in other social-ecological systems. | Social and Economic | Case study and face-to-face interviews | No | Local Food | N = 20 Local Food Systems stakeholders | N.A. | G, H | [95] |

| Tookes et al., 2018 | To examine the interplay between demand for local and ethically sourced foods and the implications for seafood sustainability in the U.S. south. | Social, Economic, and Environment | Face-to-face survey | Yes | Local Seafood | N = 500 Farmers market shoppers | LS | H | [52] |

| Vitali et al., 2018 | To assess greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions associated with a local organic beef supply chain using a cradle-to-grave approach. | Environment | Life Cycle Assessment | No | Local Organic Beef | N.A. | N.A. | G | [84] |

| Baldy, 2019 | To identify how local actors are framing the food system and what this means for increasing sustainability. | Social, Economic, and Environment | Case study; participatory observation; workshops and face-to-face interviews | No | Local Food | N = 26 Local Food Systems stakeholders | N.A. | G | [96] |

| Beingessner and Flecher, 2019 | To examine local food systems from the producer perspective in a rural context of high industrialization and geographical dispersion. | Social and Economic | Case study; face-to-face interviews and focus groups | No | Local Food | N = 60 Local Food Systems stakeholders | N.A. | H | [100] |

| Bernard et al., 2019 | To examine the impacts of minimal-information labels using field experiments with watermelons. | Economic | Face-to-face interviews | No | Value-added labels | N = 328 Consumers | N.A. | G | [91] |

| Bryla, 2019 | To assess the level and predictors of regional ethnocentrism on the market of regional food products in the context of sustainable consumption. | Economic | Computer-assisted web interview | No | Regional Ethnocentrism | N = 1000 Consumers | N.A. | R | [133] |

| Chen et al., 2019 | To analyze how the motivation, barriers, and methods of advertisement influence the participation dynamics of CSA by segmenting consumers based on their past, current, and future CSA participation. | Social and Economic | Online survey | Yes | CSA | N = 795 Consumers | N.A. | H | [29] |

| Corsi and Mazzocchi, 2019 | To assesses the agricultural and territorial drivers that influence the development of AFNs. | Social | Data analysis of the factors influencing the participation of consumers and farmers in AFNs using an Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression | No | Alternative Food Networks | N.A | N.A | H | [128] |

| Denver et al., 2019 | To investigate the preferences and trade-offs of distinct consumer segments relative to organic production and several dimensions of local food. | Economic | Online survey; choice experiment | No | Local and Organic Food | N = 505 Consumers | N.A. | G | [85] |

| Fan et al., 2019 | To assess the effect of locally grown information on consumer WTP and quality perceptions of three broccoli varieties. | Economic | Sensory evaluation of broccoli using affective test | No | Local Food | N = 240 Consumers | N.A. | G | [86] |

| Meyerdin et al., 2019 | To explore whether consumers prefer specific local food labeling strategies to others, and where there is a difference between fresh and processed tomatoes. | Economic | Face-to-face to survey; choice-based conjoint analysis | Yes | Local Food | N = 640 German Consumers | PS | G | [15] |

| Nakandala and Lau, 2019 | To investigate the characteristics of demand and supply in relation to the real-world supply chain strategies of local urban fresh food supply chains. | Social and Economic | Case study; face-to-face interviews | Yes | Urban fresh food supply chains | N = 12 Urban local fresh food retailers | IS | G | [41] |

| Nicolosi et al., 2019 | To analyze the preferences of Swedish consumers for local/artisanal cheeses and the purchase motivations that guide their choices. | Social | Face-to-face interviews; social network analysis | No | Local Food | N = 200 Consumers | N.A. | H, R | [122] |

| Olson et al., 2019 | To assesses the impact of the local food economy in Hardwick using environmental, economic, and social outcomes. | Social, Economic, and Environment | Face-to-face interviews | No | Local Food | N = 21 Local Food Systems stakeholders | N.A. | R | [131] |

| Osei-Owusu et al., 2019 | To assesses the global cropland footprint of Danish food and feed supply. | Environment | Data analysis assessing the global cropland footprint of Danish food and feed supply from 2000 to 2013 using a consumption-based physical accounting approach | No | Footprint | N.A. | N.A. | G | [92] |

| Paul, 2019 | To investigate if a new model of farming—CSA—is delivering sustainable livelihoods to farmers. | Social and Economic | Face-to-face interviews | No | CSA | N = 14 CSA farmers | N.A. | H | [122] |

| Profeta and Hamm, 2019 | To analyze if a local feed origin labelling is a promising strategy to accompany the efforts being made in the production of local feedstuffs. | Social and Economic | Computer self-assisted personal interviews; discrete-choice experiment | No | Local Food | N = 1602 Consumers | N.A. | H | [101] |

| Santo and Moragues-Faus, 2019 | To examine the trans-local dimension of food policy networks and its potential to facilitate transformative food system reform. | Social and Economic | Case study; participant observation; face-to-face interviews | No | Local Food | N = 22 Trans-local food policy networks projects members | N.A. | G | [98] |

| Tang et al., 2019 | To identify the experiences and current problems and demonstrating recent research and development status of CSA in China. | Social, Economic, and Environment | Data analysis of CSA status in China | No | CSA | Data analysis | N.A. | H | [124] |

| Tatebayashi et al., 2019 | To identify the structure of food-sharing networks and non- market food species. | Social | Face-to-face interviews and online survey | Yes | Food Sharing Network | N = 281 Farmers (n = 15); consumers (251) | IS | H | [43] |

| Werner et al., 2019 | To identify key factors of understanding local food systems from a regional perspective. | Social and Economic | Online and mailed survey; discrete choice analysis; data analysis of farmland acreage | No | Local Food | N = 756 Restaurants (n = 109); consumers (n = 647) | N.A. | G | [87] |

| Witzling and Shaw, 2019 | To understand local food consumers and take steps to begin to identify how targeted messages could engage different groups. | Economic | Mailed survey | No | Local Food | N = 577 Consumers | N.A. | H | [102] |

| Bareja-Wawryszuk, 2020 | To analyze of the forms of organization and spatial concentration of local food systems in Poland. | Economic | Data analysis based on the register of local entities to identify and characterize the forms of organization of local food systems in Poland | No | Local Food | N = 1067 Consumers | N.A. | G | [88] |

| Barska and Wojciechowska-Solis, 2020 | To identify the behavior of Polish consumers shopping online for local food products and to identify barriers to purchase. | Economic | Online survey | No | Local Food | N = 1067 Consumers | N.A. | G, H | [97] |

| Birtalan et al., 2020 | To explore food-related well-being among CSA members. | Social and Economic | Face-to-face interviews; thematic analysis | Yes | CSA | N = 35 CSA members | LS | H | [53] |

| Bisht, 2020 | To explore the effects of the implementation of sustainability practices to traditional farming and food systems. | Social and Economic | Focus-group | No | Local and Organic Food | N = 1000 Farmers | N.A. | H | [125] |

| Fogarassy et al., 2020 | To explore the circular characteristics of consumers’ attitude towards food purchasing in Hungary. | Economic | Face-to-face interviews | No | Circular Economy and Organic Food | N = 828 Consumers | N.A. | H | [129] |

| Horská et al., 2020 | To identify the factors that influence the sales of local products with a focus on value-added dairy products. | Social and Economic | Case study; face-to-face interviews | No | Short Food Supply Chains | N = 30 Family Farms | N.A. | H | [127] |

| Kopczyńska, 2020 | To compare the collectives based on novel alternative food networks and traditional networks. | Social, Economic, and Environment | Face-to-face interviews | Yes | Local Food | N = 38 Consumers | IS | H | [42] |

| Ku and Kan, 2020 | To examines the potential contribution of social work intervention in responding to China’s agrarian challenges. | Social and Economic | Case study; participatory action research | No | Local Food | N = 347 Households | N.A. | H, R | [126] |

| Marchetti et al., 2020 | To present and denounce environmentally and socially unsustainable agricultural practice, which cause negative effects on environment, health, and social and intergenerational equity. | Social, Economic, and Environment | Grounded theory approach; desk analysis to detail some directions and perspectives about food production systems and sustainability | No | Food Production System | N.A. | N.A. | H | [22] |

| Oravecz et al., 2020 | To identify the main characteristics of Hungarian consumer preferences when buying honey. | Economic | Face-to-face interviews | No | Local Food | N = 1584 Consumers | N.A. | G | [89] |

| Printezis and Grebitus et al., 2020 | To investigate the preferences and willingness to pay of college student millennials for unprocessed (fresh) or processed (typically come in a container) food products sold at urban farms. | Economic | Online survey; choice experiment | No | Urban Agriculture | N = 443 College Students | N.A. | G | [93] |

| Sanjuán-López and Resano-Ezcaray, 2020 | To analyze the willingness to pay for the local, organic, and PDO (Protected Designation of Origin), their differences across experimental conditions, and by identifying the effects of personal characteristics. | Economic | Face-to-face interviews; choice experiment with the Random Utility Model | No | Local Food | N = 208 Consumers | N.A. | R | [134] |

| Tremblay et al., 2020 | To identify and describe the dietary importance of different wild animal species across the range of communities included and assess the extent to which dietary diversity correlates with geography, culture, and ecology. | Social and Environment | Case study and face-to-face interviews | No | Local Food | N = 21 Indigenous communities | N.A. | R | [130] |

| González-azcárate et al., 2021 | To achieve a better understanding of SFSCs in terms of potential market niches, key food choice attributes, and perceived barriers and drivers. | Social, Economic, and Environment | Face-to-face and random telephone survey | No | Short Food Supply Chains | N = 1969 Active SFSC consumers (N = 394); potential SFSC consumers (N = 422) and the general public in Spain (N = 1153). | N.A. | G | [94] |

| Kim and Huang, 2021 | To develop a novel framework of local food consumption which explores the dynamic relationships among local food ideology. | Economic | Online survey | No | Local Food | N = 297 Consumers | N.A. | G, H, R | [56] |

| Kuhl et al., 2021 | To analyze how an ideal local beef production should be constituted. | Economic | Online survey | No | Local Beef | N = 432 Consumers | N.A. | G | [57] |

| Moreno and Malone, 2021 | To explore the interaction between local food identity and agricultural production. | Economic | Online survey; discrete choice experiment | No | Local Food | N = 484 Consumers | N.A. | R | [135] |

References

- Beeton, R.J.S.; Buckley, K.I.; Jones, G.J.; Morgan, D.; Reichelt, R.E.; Trewin, D. Australia State of the Environment; Department of the Environment and Heritage: Canberra, Australia, 2006; ISBN 0642553009. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Economic and Social Council (UN-ESC). Work on the Review of Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2017; Volume 22160, pp. 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Napoli, G.; Barbaro, S.; Giuffrida, S.; Trovato, M.R. The Lombardy Green Deal: New Challenges for the Economic Feasibility of Energy Retrofit at District Scale; Springer Nature: Basingstoke, UK, 2021; Volume 178, ISBN 9783030482787. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Garnett, T. Food sustainability: Problems, perspectives and solutions. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2013, 72, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fischer, C.G.; Garnett, T. Plates, Pyramids, Planet: Developments in National Healthy and Sustainable Dietary Guidelines: A State of Play Assessment; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy; The Food Climate Research Network at The University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2016; ISBN 9789251092224. [Google Scholar]

- Verain, M.C.D.; Bartels, J.; Dagevos, H.; Sijtsema, S.J.; Onwezen, M.C.; Antonides, G. Segments of sustainable food consumers: A literature review. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2012, 36, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfang, G. The New Economics of Sustainable Consumption; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-0-230-23450-5. [Google Scholar]

- Heijungs, R.; Huppes, G.; Guinée, J.B. Life cycle assessment and sustainability analysis of products, materials and technologies. Toward a scientific framework for sustainability life cycle analysis. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2010, 95, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, M.J.; Sutherland, J.W. An exploration of measures of social sustainability and their application to supply chain decisions. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1688–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, M.K.; Sobal, J. Sustainable Food Activities among Consumers: A Community Study Consumers. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2013, 8, 379–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, J.; Szabo, M.; Rodney, A. Good food, good people: Understanding the cultural repertoire of ethical eating. J. Consum. Cult. 2011, 11, 293–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Kane, G. A moveable feast: Exploring barriers and enablers to food citizenship. Appetite 2016, 105, 674–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerding, S.G.H.; Trajer, N.; Lehberger, M. What is local food? The case of consumer preferences for local food labeling of tomatoes in Germany. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 30–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, F.C.F.C.; Coelho, E.M.E.M.; Egerer, M. Local food: Benefits and failings due to modern agriculture. Sci. Agric. 2018, 75, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brooks, M.; Foster, C.; Holmes, M.; Wiltshire, J. Does consuming seasonal foods benefit the environment? Insights from recent research. Nutr. Bull. 2011, 36, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DEFRA. Understanding the Environmental Impacts of Consuming Foods That Are Produced Locally in Season; DEFRA: London, UK, 2012.

- Foster, C.; Guében, C.; Holmes, M.; Wiltshire, J.; Wynn, S. The environmental effects of seasonal food purchase: A raspberry case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 73, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdiarmid, J.I. Seasonality and dietary requirements: Will eating seasonal food contribute to health and environmental sustainability? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2014, 73, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scalvedi, M.L.M.L.; Saba, A. Exploring local and organic food consumption in a holistic sustainability view. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, L.; Cattivelli, V.; Cocozza, C.; Salbitano, F.; Marchetti, M. Beyond sustainability in food systems: Perspectives from agroecology and social innovation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilkins, J.L.J.L.; Bowdish, E.; Sobal, J. Consumer perceptions of seasonal and local foods: A study in a U.S. community. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2002, 41, 415–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, J.; de Witt, A.; Aiking, H. Help the climate, change your diet: A cross-sectional study on how to involve consumers in a transition to a low-carbon society. Appetite 2016, 98, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Chabert-Rios, J.; Deale, C.S. Taking the local food movement one step further: An exploratory case study of hyper-local restaurants. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2018, 18, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, B.; Byun, R.; Mitchell, E.; Thompson, S.; Jalaludin, B.; Torvaldsen, S. Seeking fresh food and supporting local producers: Perceptions and motivations of farmers’ market customers. Aust. Plan. 2018, 55, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Gao, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, L. Factors affecting the dynamics of community supported agriculture (CSA) membership. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Röös, E.; Karlsson, H. Effect of eating seasonal on the carbon footprint of Swedish vegetable consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 59, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.C.; Worsley, A.; Hodgson, V. Classification of main meal patterns-a latent class approach. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 109, 2285–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilkins, L. Seasonality, Food Origin, and Food Preference: A Comparison between Food Cooperative Members and Nonmembers. Soc. Nutr. Educ. 1996, 28, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selfa, T.; Qazi, J. Place, taste, or face-to-face? Understanding producer-consumer networks in “local” food systems in Washington State. Agric. Hum. Values 2005, 22, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnoult, M.; Lobb, A.; Tiffin, R. Willingness to pay for imported and seasonal foods: A UK survey. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2010, 22, 234–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milestad, R.; Bartel-Kratochvil, R.; Leitner, H.; Axmann, P. Being close: The quality of social relationships in a local organic cereal and bread network in Lower Austria. J. Rural Stud. 2010, 26, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, A.L.M.; Winham, D.M.; Wharton, C.M. Community supported agriculture membership in Arizona. An exploratory study of food and sustainability behaviours. Appetite 2012, 59, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnell, S.M. Food miles, local eating, and community supported agriculture: Putting local food in its place. Agric. Hum. Values 2013, 30, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneyd, L.Q. Wild food, prices, diets and development: Sustainability and food security in Urban Lombardy. Sustainability 2013, 5, 4728–4759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balázs, B.; Pataki, G.; Lazányi, O. Prospects for the future: Community supported agriculture in Hungary. Futures 2016, 83, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakos, I.M.I.M. Local food systems supported by communities nationally and internationally. Deturope 2017, 9, 59–79. [Google Scholar]

- Nakandala, D.; Lau, H.C.W. Innovative adoption of hybrid supply chain strategies in urban local fresh food supply chain. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2019, 24, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopczyńska, E. Are there local versions of sustainability? Food networks in the semi-periphery. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tatebayashi, K.; Kamiyama, C.; Matsui, T.; Saito, O.; Machimura, T. Accounting shadow benefits of non-market food through food-sharing networks on Hachijo Island, Japan. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutson, R.D.; Palma, M.A.; Paggi, M.; Seale, J.; Ribera, L.A.; Bessler, D. Role of Trade in Satisfying U.S. Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Demand. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2014, 26, 326–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, D.; Henryks, J.; Trott, A.; Jones, P.; Parker, G.; Dumaresq, D.; Dyball, R. Local food: Understanding consumer motivations in innovative retail formats. Br. Food J. 2011, 113, 886–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amate, J.I.; González De Molina, M. “Sustainable de-growth” in agriculture and food: An agro-ecological perspective on Spain’s agri-food system (year 2000). J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 38, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, S. Minimising food miles: Issues and outcomes in an ecotourism venture in Fiji. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 1148–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiffoleau, Y.; Millet Amrani, S.; Canard, A. From short food supply chains to sustainable agriculture in urban food systems: Food democracy as a vector of transition. Agriculture 2016, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Darolt, R.M.; Lamine, C.; Brandenburg, A.; Alencar, M.C.F.; Abreu, L.S. Alternative food networks and new producer-consumer relations in France and in Brazil. Ambient. Soc. 2016, 19, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hvitsand, C. Community supported agriculture (CSA) as a transformational act—distinct values and multiple motivations among farmers and consumers. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2016, 40, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merle, A.; Herault-fournier, C.; Werle, C.O. The effects of indication of local geographical origin on food perceptions. Rech. Appl. Mark. 2016, 31, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tookes, J.S.; Barlett, P.; Yandle, T. The Case for Local and Sustainable Seafood: A Georgia Example. Cult. Agric. Food Environ. 2018, 40, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birtalan, I.L.; Bartha, A.; Neulinger, Á.; Bárdos, G.; Oláh, A.; Rácz, J.; Rigó, A.; Neulinger, A. Community supported agriculture as a driver of food-related well-being. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, E.; Dominique, B.; Six, J. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems Assessing the degree of localness of food value chains Assessing the degree of localness of food value chains. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 42, 573–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunori, G. Local food and alternative food networks: A communication perspective. Anthropol. Food 2007, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Huang, R. Understanding local food consumption from an ideological perspective: Locavorism, authenticity, pride, and willingness to visit. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhl, S.; Busch, G.; Gauly, M. How should beef be produced? Consumer expectations and views on local beef production in South Tyrol (Italy). Br. Food J. 2021, 123, 1578–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda, L.; Leviten-Reid, C. Consumers’ Views on Local Food. J. Food Distrib. Res. 2004, 35, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirieix, L.; Grolleau, G.; Schaer, B. Do consumers care about food miles? An empirical analysis in France. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.L.; Matthews, H.S. Food-Miles and the Relative Climate Impacts of Food Choices in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 3508–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Coley, D.; Howard, M.; Winter, M. Local food, food miles and carbon emissions: A comparison of farm shop and mass distribution approaches. Food Policy 2009, 34, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, P.; Edwards, R.T.; Opondo, M.; Nyeko, P.; Edwards-Jones, G. Does farm worker health vary between localised and globalised food supply systems? Environ. Int. 2009, 35, 1004–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nousiainen, M.; Pylkkänen, P.; Saunders, F.; Seppänen, L.; Vesala, K.M.K.M. Are alternative food systems socially sustainable? A case study from finland. J. Sustain. Agric. 2009, 33, 566–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepeda, L.; Deal, D. Organic and local food consumer behaviour: Alphabet theory. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, D.; Colasanti, K.; Ross, R.B.; Smalley, S.B. Locally grown foods and farmers markets: Consumer attitudes and behaviors. Sustainability 2010, 2, 742–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Louden, F.N.; MacRae, R.J. Federal regulation of local and sustainable food claims in Canada: A case study of Local Food Plus. Agric. Hum. Values 2010, 27, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, M.; Sharp, J.S. Profiling alternative food system supporters: The personal and social basis of local and organic food support. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2011, 26, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, F.F.; Stanton, J.L.; Wiley, J.B. The relative importance of search versus credence product attributes: Organic and locally grown. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2011, 40, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Batte, M.T.; Woods, T.; Ernst, S. Consumer preferences for local production and other value-added label claims for a processed food product. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2012, 39, 489–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainbolt, G.N.; Onozaka, Y.; McFadde, D.T. Consumer Motivations and Buying Behavior: The Case of the Local Food System Movement. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2012, 18, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverría, R.; Moreira, V.H.; Sepúveda, C.; Wittwer, C. Willingness to pay for carbon footprint on foods. Br. Food J. 2014, 116, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillywhite, J.M.; Simonsen, J.E. Consumer Preferences for Locally Produced Food Ingredient Sourcing in Restaurants. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2014, 20, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, D.A.; Carruth, A.; Mazaroli, D.N. Operationalizing local food: Goals, actions, and indicators for alternative food systems. Agric. Hum. Values 2015, 32, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aprile, M.C.; Caputo, V.; Nayga, R.M. Consumers’ Preferences and Attitudes toward Local Food Products. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2016, 22, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, E.; Barjolle, D.; Tanquerey-Cado, A.; Brunori, G. Sustainability comparison of a local and a global milk value chains in Switzerland. Bio Based Appl. Econ. 2016, 5, 175–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touzard, J.-M.; Chiffoleau, Y.; Maffezzoli, C. What is local or global about wine? An attempt to objectivize a social construction. Sustainability 2016, 8, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berg, N.; Preston, K.L. Willingness to pay for local food?: Consumer preferences and shopping behavior at Otago Farmers Market. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2017, 103, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C. Exploring Urban Consumers’ Attitudes and Intentions to Purchase Local Food in Chile. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2017, 23, 553–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granvik, M.; Joosse, S.; Hunt, A.; Hallberg, I. Confusion and misunderstanding-Interpretations and definitions of local food. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schoolman, E.D. Do direct market farms use fewer agricultural chemicals? Evidence from the US census of agriculture. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2019, 34, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telligman, A.L.; Worosz, M.R.; Bratcher, C.L. “Local” as an indicator of beef quality: An exploratory study of rural consumers in the southern U.S. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 57, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tichenor, N.E.; Peters, C.J.; Norris, G.A.; Thoma, G.; Griffin, T.S. Life cycle environmental consequences of grass-fed and dairy beef production systems in the Northeastern United States. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 1619–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, L.C.; DeLong, K.L.; Jensen, K.L.; Griffith, A.P.; Boyer, C.N.; Lambert, D.M. Estimating restaurant willingness to pay for local beef. Agribusiness 2019, 35, 610–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vitali, A.; Grossi, G.; Martino, G.; Bernabucci, U.; Nardone, A.; Lacetera, N. Carbon footprint of organic beef meat from farm to fork: A case study of short supply chain. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 5518–5524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denver, S.; Jensen, J.D.J.D.; Olsen, S.B.S.B.; Christensen, T. Consumer Preferences for ‘Localness’ and Organic Food Production. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2019, 25, 668–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Gómez, M.I.; Coles, P.S. Willingness to Pay, Quality Perception, and Local Foods: The Case of Broccoli. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2019, 3, 414–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Werner, S.; Lemos, S.R.; McLeod, A.; Halstead, J.M.; Gabe, T.; Huang, J.C.; Liang, C.L.; Shi, W.; Harris, L.; McConnon, J. Prospects for New England Agriculture: Farm to Fork. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2019, 48, 473–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bareja-Wawryszuk, O. Forms of organization and spatial concentration of local food systems. A case from Poland. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2020, 8, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oravecz, T.; Mucha, L.; Magda, R.; Totth, G.; Illés, C.B. Consumers’ preferences for locally produced honey in Hungary. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brunensis 2020, 68, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pícha, K.; Navrátil, J.; Švec, R. Preference to Local Food vs. Preference to “National” and Regional Food. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2018, 24, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, J.C.; Duke, J.M.; Albrecht, S.E. Do labels that convey minimal, redundant, or no information affect consumer perceptions and willingness to pay ? Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 71, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei-Owusu, A.K.; Kastner, T.; de Ruiter, H.; Thomsen, M.; Caro, D. The global cropland footprint of Denmark’s food supply 2000–2013. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 58, 01978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Printezis, I.; Grebitus, C. College-Age Millennials’ Preferences for Food Supplied by Urban Agriculture. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Azcárate, M.; Luis, J.; Maceín, C.; Bardají, I. Why buying directly from producers is a valuable choice? Expanding the scope of short food supply chains in Spain. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 911–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skog, K.L.; Eriksen, S.E.; Brekken, C.A.; Francis, C. Building resilience in social-ecological food systems in Vermont. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Baldy, J. Framing a sustainable local food system-how smaller cities in southern Germany are facing a new policy issue. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barska, A.; Wojciechowska-Solis, J. E-consumers and local food products: A perspective for developing online shopping for local goods in Poland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santo, R.; Moragues-Faus, A. Towards a trans-local food governance: Exploring the transformative capacity of food policy assemblages in the US and UK. Geoforum 2019, 98, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulick, R. More time in the kitchen, less time on the streets: The micropolitics of cultivating an ethic of care in alternative food networks. Local Environ. 2019, 24, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beingessner, N.; Fletcher, A.J. “Going local”: Farmers’ perspectives on local food systems in rural Canada. Agric. Hum. Values 2020, 37, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Profeta, A.; Hamm, U. Do consumers care about local feedstuffs in local food? Results from a German consumer study. NJAS—Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2019, 88, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witzling, L.; Shaw, B.R. Lifestyle segmentation and political ideology: Toward understanding beliefs and behavior about local food. Appetite 2019, 132, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roininen, K.; Arvola, A.; Lähteenmäki, L. Exploring consumers’ perceptions of local food with two different qualitative techniques: Laddering and word association. Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 17, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, B.; Purcell, M. Avoiding the local trap: Scale and food systems in planning research. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2006, 26, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levidow, L.; Psarikidou, K. Food Relocalization for Environmental Sustainability in Cumbria. Sustainability 2011, 3, 692–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hayden, J.; Buck, D. Doing community supported agriculture: Tactile space, affect and effects of membership. Geoforum 2012, 43, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubry, C.; Kebir, L. Shortening food supply chains: A means for maintaining agriculture close to urban areas? The case of the French metropolitan area of Paris. Food Policy 2013, 41, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonte, M. Food consumption as social practice: Solidarity Purchasing Groups in Rome, Italy. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 32, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, M.A.; Murray, D.L. Ethical Consumption, Values Convergence/Divergence and Community Development. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2013, 26, 351–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundler, P.; Laughrea, S. The contributions of short food supply chains to territorial development: A study of three Quebec territories. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 45, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellante, L. Building the local food movement in Chiapas, Mexico: Rationales, benefits, and limitations. Agric. Hum. Values 2017, 34, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lurie, S.; Brekken, C.A. The role of local agriculture in the new natural resource economy (NNRE) for rural economic development. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2019, 34, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, J.; Smetschka, B.; Grima, N. Farmer cooperation as a means for creating local food systems-Potentials and challenges. Sustainability 2017, 9, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Russell, W.S.; Zepeda, L. The adaptive consumer: Shifting attitudes, behavior change and CSA membership renewal. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2008, 23, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeurwaerdere, T.; De Schutter, O.; Hudon, M.; Mathijs, E.; Annaert, B.; Avermaete, T.; Bleeckx, T.; de Callataÿ, C.; De Snijder, P.; Fernández-Wulff, P.; et al. The Governance Features of Social Enterprise and Social Network Activities of Collective Food Buying Groups. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 140, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Favilli, E.; Rossi, A.; Brunori, G. Food networks: Collective action and local development. The role of organic farming as boundary object. Org. Agric. 2015, 5, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memery, J.; Angell, R.; Megicks, P.; Lindgreen, A. Unpicking motives to purchase locally-produced food: Analysis of direct and moderation effects. Eur. J. Mark. 2015, 49, 1207–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, J.T.; Bunn, C. Growing in Glasgow: Innovative practices and emerging policy pathways for urban agriculture. Land Use Policy 2017, 68, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schmutz, U.; Kneafsey, M.; Kay, C.S.; Doernberg, A.; Zasada, I. Sustainability impact assessments of different urban short food supply chains: Examples from London, UK. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2018, 33, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Furman, C.A.; Papavasiliou, F. Scale and affect in the local food movement. Food Cult. Soc. 2018, 21, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, S.; Migliore, G.; Schifani, G.; Schimmenti, E.; Padel, S. Motives for buying local, organic food through English box schemes. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 1600–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolosi, A.; Laganà, V.R.; Laven, D.; Marcianò, C.; Skoglund, W. Consumer habits of local food: Perspectives from northern Sweden. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paul, M. Community-supported agriculture in the United States: Social, ecological, and economic benefits to farming. J. Agrar. Chang. 2019, 19, 162–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Liu, Y.; Huang, G. Current status and development strategy for community-supported agriculture (CSA) in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bisht, I.S.; Rana, J.C.; Ahlawat, S.P. The future of smallholder farming in India: Some sustainability considerations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, H.B.; Kan, K. Social work and sustainable rural development: The practice of social economy in China. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 2020, 29, 346–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horská, E.; Petriľák, M.; Šedík, P.; Nagyová, Ľ. Factors influencing the sale of local products through short supply chains: A case of family dairy farms in Slovakia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsi, S.; Mazzocchi, C. Alternative food networks (AFNs): Determinants for consumer and farmer participation in Lombardy, Italy. Agric. Econ. 2019, 65, 259–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarassy, C.; Nagy-Pércsi, K.; Ajibade, S.; Gyuricza, C.; Ymeri, P. Relations between circular economic “principles” and organic food purchasing behavior in Hungary. Agronomy 2020, 10, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, R.; Landry-Cuerrier, M.; Humphries, M.M. Culture and the social-ecology of local food use by indigenous communities in northern North America. Ecol. Soc. 2020, 25, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, K.A. The town that food saved? Investigating the promise of a local food economy in Vermont. Local Environ. 2019, 24, 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C.; Buller, H. The local food sector: A preliminary assessment of its form and impact in Gloucestershire. Br. Food J. 2003, 105, 559–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryła, P. Regional ethnocentrism on the food market as a pattern of sustainable consumption. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sanjuán-López, A.I.; Resano-Ezcaray, H. Labels for a Local Food Speciality Product: The Case of Saffron. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 71, 778–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, F.; Malone, T. The Role of Collective Food Identity in Local Food Demand. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2021, 50, 22–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrin, M.; Gussow, J.D. Designing a sustainable regional diet. J. Nutr. Educ. 1989, 21, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, S.; Hand, M.; Da Pra, M.; Pollack, S.; Ralston, K.; Smith, T.; Vogel, S.; Clark, S.; Lohr, L.; Low, S.; et al. Local Food Systems: Concepts, Impacts, and Issues; Economic Research Report; DIANE Publishing: Collingdale, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- European Parliament. Commission Delegated Regulation (Eu) No 807/2014 of 11 March 2014. Off. J. Eur. Union 2014, L 227/1, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Conseil de Développement du Pays d’Ancenis (COMPA). Circuits Courts Alimentaires de Proximite en Pays d’Ancenis; Conseil de Développement du Pays d’Ancenis (COMPA): Ancenis, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kneafsey, M.; Venn, L.; Schmutz, U.; Balázs, B. Short Food Supply Chains and Local Food Systems in the EU. A State of Play of their Socio-Economic Characteristics. In Citizen Science to Promote Creativity, Scientific Literacy, and Innovation throughout Europe View Project Agroecology and Organic Horticult; JRC Scientific and Policy Reports; Joint Research Centre (JRC): Ispra, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwil, I.; Piwowar-Sulej, K. Local Entrepreneurship in the Context of Food Production: A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sheth, J.N.; Sethia, N.K.; Srinivas, S. Mindful consumption: A customer-centric approach to sustainability. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, C. Explaining seasonal patterns of food consumption. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2021, 24, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomaier, S.; Specht, K.; Henckel, D.; Dierich, A.; Siebert, R.; Freisinger, U.B.; Sawicka, M. Farming in and on urban buildings: Present practice and specific novelties of Zero-Acreage Farming (Zfarming). Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2014, 30, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Specht, K.; Siebert, R.; Hartmann, I.; Freisinger, U.B.; Sawicka, M.; Werner, A.; Thomaier, S.; Henckel, D.; Walk, H.; Dierich, A. Urban agriculture of the future: An overview of sustainability aspects of food production in and on buildings. Agric. Hum. Values 2014, 31, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahnya, D.L. Analysis of urban agriculture sustainability in Metropolitan Jakarta (case study: Urban agriculture in Duri Kosambi). Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 227, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Graamans, L.; Baeza, E.; Van Den Dobbelsteen, A.; Tsafaras, I.; Stanghellini, C. Plant factories versus greenhouses: Comparison of resource use efficiency. Agric. Syst. 2018, 160, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, A.; Ray, R.; Sreevidya, E.A. How Many Wild Edible Plants Do We Eat—Their Diversity, Use, and Implications for Sustainable Food System: An Exploratory Analysis in India. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paumgarten, F. Wild Foods: Safety Net or Poverty Trap? A South African Case Study. Hum. Ecol. 2018, 46, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempel, C.; Hamm, U. How important is local food to organic-minded consumers? Appetite 2016, 96, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, C.V.; Allen, M.W. Human Values and Consumer Choice in Australia and Brazil. Psicol. Teor. Pesqui. 2009, 25, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zukin, S.; Maguire, J.S. Consumers and Consumption. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2004, 30, 97–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peattie, K. Green Consumption: Behavior and Norms. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2010, 35, 195–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Gill, O. Willingness-to-Pay: A Welfarist Reassessment; Harvard Law School: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; Volume 5349, ISBN 1936-5357. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, C.A.; Levy, R.B. A new classification of foods based on the extent and purpose of their processing: Uma nova classificação de alimentos baseada na extensão e propósito do seu processamento. Cad. Saúde Pública 2010, 26, 2039–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Costanigro, M.; Deselnicu, O.; Kroll, S. Food beliefs: Elicitation, estimation and implications for labeling policy. J. Agric. Econ. 2015, 66, 108–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DuPuis, E.M.; Goodman, D. Should we go “home” to eat?: Toward a reflexive politics of localism. J. Rural Stud. 2005, 21, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, P.; Nei, D.; Orikasa, T.; Xu, Q.; Okadome, H.; Nakamura, N.; Shiina, T. A review of life cycle assessment (LCA) on some food products. J. Food Eng. 2009, 90, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Database | Search Strategy | |

|---|---|---|

| Scopus and Web of Science | Search 1 #1 | Seasonal food |

| Search 1 #2 | Seasonal* AND Sustainability | |

| Search 1 #3 | Seasonal* AND Short Supply Chain | |

| Search 1 #4 | Seasonal* AND Consumer | |

| Search 1 #5 | Seasonal* AND Circular Economy | |

| Search 2 #1 | Local food | |

| Search 2 #2 | Local food AND Sustainability | |

| Search 2 #3 | Local food AND Short Supply Chain | |

| Search 2 #4 | Local food AND Consumer | |

| Search 2 #5 | Local food AND Circular Economy |

| Concepts | Definition | References |

|---|---|---|

| In season | Linked only to natural food availability e.g., “uncertainties of seasonality and weather in production planning is the primary requirement of economically viable farming” [31] | [14,21,25,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43] |

| Produced in Season | Linked simultaneously to availability and type of production. Food that is produced in their natural growing season, without high energy use for climate modification. e.g., “The range of fresh products is made available either through imports from countries where the growing season is longer or occurs at a different time of the year or through energy-demanding technologies that extend the normal growing season, predominantly heated greenhouses” [29] | [15,17,19,30,44] |

| Local Seasonal | Linked simultaneously to availability, location, and type of production. The food is produced and consumed within geographical proximity. It is produced outdoors in its natural growing season, without high energy use for climate modification or storage. e.g., “CSA programs encourage local production and consumption by allowing consumers to subscribe to a membership and, in return, receive food periodically from a group of local farmers during the harvest season” [28] | [17,19,21,26,27,28,29,30,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53] |

| Concepts | Definition | References |

|---|---|---|

| Geographic | Food is produced in a geographic proximity or in a specific political boundary, e.g., Tomato from within a 50 km radius or a German Tomato | [15,17,19,21,25,26,27,28,30,32,33,34,38,41,46,47,51,54,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98] |

| Holistic | Food produced in geographic proximity with trust and connectedness between and within producer groups and consumers. It is mainly represented by short food supply chains and cooperative networks of consumers and producers that commonly pursue to maintain traditional farming practices through new models and social improvement; e.g., Community-Supported Agriculture (CSA) | [14,22,29,35,36,37,39,40,42,43,45,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,56,79,90,97,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129] |

| Regional | Food that represents concepts such as “specialty” and “identity”, containing a differentiation of the food, e.g., Parma Ham | [7,75,76,122,126,130,131,132,133,134,135] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vargas, A.M.; de Moura, A.P.; Deliza, R.; Cunha, L.M. The Role of Local Seasonal Foods in Enhancing Sustainable Food Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review. Foods 2021, 10, 2206. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10092206

Vargas AM, de Moura AP, Deliza R, Cunha LM. The Role of Local Seasonal Foods in Enhancing Sustainable Food Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review. Foods. 2021; 10(9):2206. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10092206

Chicago/Turabian StyleVargas, Alexandre Maia, Ana Pinto de Moura, Rosires Deliza, and Luís Miguel Cunha. 2021. "The Role of Local Seasonal Foods in Enhancing Sustainable Food Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review" Foods 10, no. 9: 2206. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10092206

APA StyleVargas, A. M., de Moura, A. P., Deliza, R., & Cunha, L. M. (2021). The Role of Local Seasonal Foods in Enhancing Sustainable Food Consumption: A Systematic Literature Review. Foods, 10(9), 2206. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10092206