Effects of Phlorotannins on Organisms: Focus on the Safety, Toxicity, and Availability of Phlorotannins

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

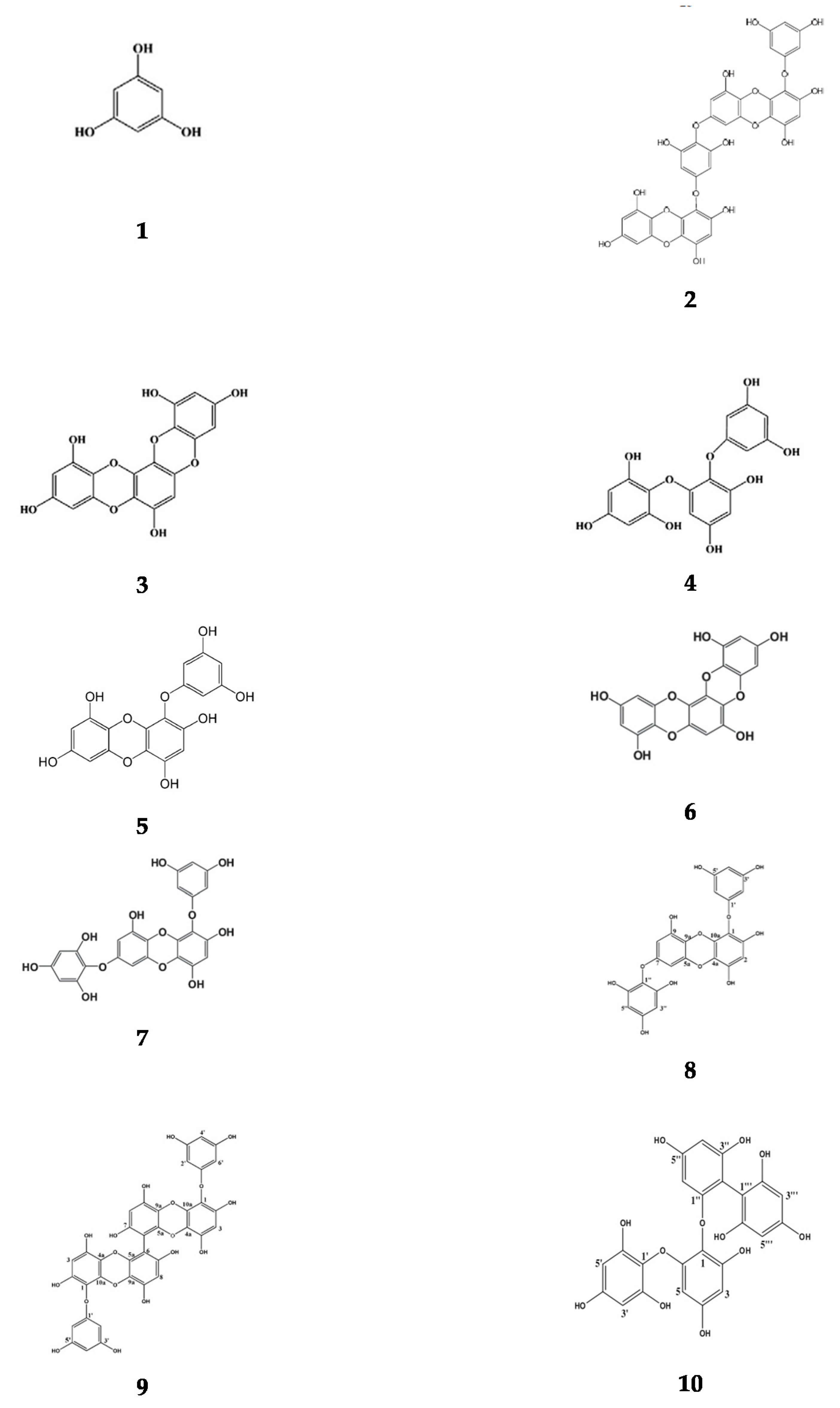

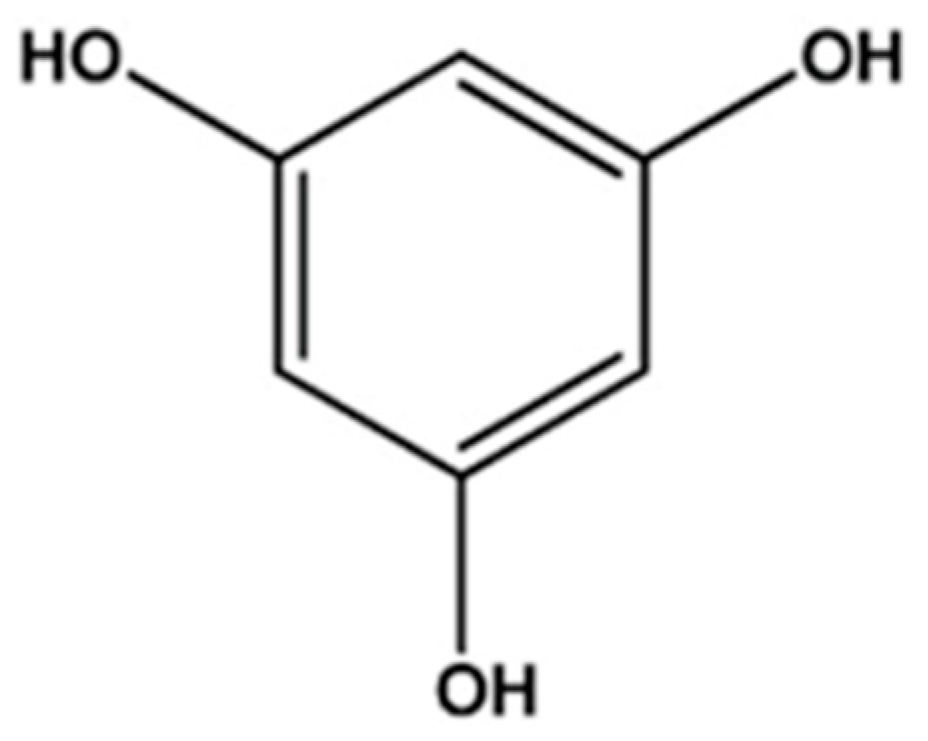

3.1. Characteristics and Structure of Phlorotannins

3.2. Safety and Toxicity of Phlorotannins in Cell Lines

3.3. Safety and Toxicity of Phlorotannins in Microalgae, Seaweeds, and Plants

3.4. Safety and Toxicity of Phlorotannins in Invertebrates

3.5. Safety and Toxicity of Phlorotannins in Animals

3.6. Safety and Toxicity of Phlorotannins in Humans

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Basic Structure of Phlorotannins Extracted from Brown Seaweeds

References

- Arnold, T.M.; Targett, N.M. Quantifying in situ rates of phlorotannin synthesis and polymerization in marine brown algae. J. Chem. Ecol. 1998, 24, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.X.; Wijesekara, I.; Li, Y.; Kim, S.K. Phlorotannins as bioactive agents from brown algae. Process Biochem. 2011, 46, 2219–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joe, M.J.; Kim, S.N.; Choi, H.Y.; Shin, W.S.; Park, G.M.; Kang, D.W.; Yong, K.K. The inhibitory effects of eckol and dieckol from Ecklonia stolonifera on the expression of matrix metalloproteinase-1 in human dermal fibroblasts. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2006, 29, 1735–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Kang, S.M.; Sok, C.H.; Hong, J.T.; Oh, J.Y.; Jeon, Y.J. Cellular activities and docking studies of eckol isolated from Ecklonia cava (laminariales, phaeophyceae) as potential tyrosinase inhibitor. Algae 2015, 30, 163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, A.X.; Hyun, Y.J.; Piao, M.J.; Devage, P.; Madushan, S. Eckol inhibits particulate matter 2, 5-induced skin keratinocyte damage via MAPK signaling pathway. Mar. Drugs. 2019, 17, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.M.; Doan, T.P.; Ha, T.K.Q.; Kim, H.W.; Lee, B.W.; Pham, H.T.T.; Cho, T.O.; Oh, W.K. Dereplication by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectroscopy (QTOF-MS) and antiviral activities of phlorotannins from Ecklonia cava. Mar. Drugs. 2019, 17, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.S.; Lee, K.; Lee, B.B.; Kim, Y.C.; Kim, Y.D.; Hong, Y.K.; Cho, K.K.; Choi, I.S. Antibacterial activity of the phlorotannins dieckol and phlorofucofuroeckol-a from Ecklonia cava against propionibacterium acnes. Bot. Sci. 2014, 92, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, S.H.; Moon, S.Y.; Lee, D.S.; Kim, H.J.; Park, K.; Lee, E.W.; Kim, T.H.; Chung, Y.H.; Lee, M.S.; Kim, Y.M. In vitro antiviral activity of dieckol and phlorofucofuroeckol-a isolated from edible brown alga Eisenia bicyclis against murine norovirus. Algae 2015, 20, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.J.; Ryu, Y.B.; Kim, Y.M.; Song, N.; Kim, C.Y.; Rho, M.C.; Jeong, J.H.; Cho, K.O.; Lee, W.S.; Park, S.J. In vitro antiviral activity of phlorotannins isolated from Ecklonia cava against porcine epidemic diarrhea coronavirus infection and hemagglutination. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 4706–4713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.S.; Jeon, H.J.; Lee, O.H.; Lee, B.Y. Dieckol, a major phlorotannin in Ecklonia cava, suppresses lipid accumulation in the adipocytes of high-fat diet-fed zebrafish and mice: Inhibition of early adipogenesis via cell-cycle arrest and AMPKα activation. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015, 59, 1458–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.W.; Song, H.; Hong, S.S.; Boo, Y.C. Marine alga Ecklonia cava extract and dieckol attenuate prostaglandin E2 production in HaCat keratinocytes exposed to airborne particulate matte. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, S.J.; Ko, S.C.; Cha, S.H.; Kang, D.H.; Park, H.S.; Choi, Y.U.; Kim, D.; Jung, W.K.; Jeon, Y.J. Effect of phlorotannins isolated from Ecklonia cava on melanogenesis and their protective effect against photo-oxidative stress induced by UV-B radiation. Toxicol In Vitro 2009, 23, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.I.; Kim, S.C.; Kim, M.K.; Boo, H.J.; Jeon, Y.J.; Koh, Y.S.; Yoo, E.S.; Kang, S.M.; Kang, H.K. Effect of dieckol, a component of Ecklonia cava, on the promotion of hair growth. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 6407–6423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.C.; Cha, S.H.; Wijesinghe, W.A.J.P.; Kang, S.M.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, E.A.; Song, C.B.; Jeon, Y.J. Protective effect of marine algae phlorotannins against AAPH-induced oxidative stress in zebrafish embryo. Food Chem. 2013, 138, 950–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadeniz, F.; Kang, K.H.; Park, J.W.; Park, S.J.; Kim, S.K. Anti-HIV-1 activity of phlorotannin derivative 8,4”-dieckol from korean brown alga Ecklonia cava. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2014, 78, 1151–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.C.; Cha, S.H.; Heo, S.J.; Lee, S.H.; Kang, S.M.; Jeon, Y.J. Protective effect of Ecklonia cava on UVB-induced oxidative stress: In vitro and in vivo zebrafish model. J. Appl. Phycol. 2011, 23, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Q.T.; Li, Y.; Qian, Z.J.; Kim, M.M.; Kim, S.K. Inhibitory effects of polyphenols isolated from marine alga Ecklonia cava on histamine release. Process Biochem. 2009, 44, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Seok, J.K.; Boo, Y.C. Ecklonia cava extract and dieckol attenuate cellular lipid peroxidation in keratinocytes exposed to PM10. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2018, 2018, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Kwon, J.M.; Kwon, H.J.; Jeong, H.J.; Kim, Y.M.; Kim, D.; Lee, W.S.; Ryu, Y.B. Dieckol, a SARS-CoV 3CL(pro) inhibitor, isolated from the edible brown algae Ecklonia cava. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 3730–3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, M.Y.; Kim, J.Y.; Han, J.K.; Kim, J.; Yang, H.; Yoon, M.; Kim, J.; Kang, S.W.; Cho, S. Phlorotannin supplement decreases wake after sleep onset in adults with self-reported sleep disturbance: A randomized, controlled, double-blind clinical and polysomnographic study. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artan, M.; Li, Y.; Karadeniz, F.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, M.M.; Kim, S.K. Anti-HIV-1 Activity of phloroglucinol derivative, 6,6′-bieckol, from Ecklonia cava. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 7921–7926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Li, Y.; Shi, X.; Kim, S.K. Inhibition of the expression on MMP-2, 9 and morphological changes via human fibrosarcoma cell line by 6,6′-bieckol from marine alga Ecklonia cava. BMB Rep. 2010, 43, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, M.J.; Yoon, K.D.; Min, S.Y.; Lee, J.S.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, T.G.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, N.G.; Huh, H.; Kim, J. Inhibition of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and protease by phlorotannins from the brown alga Ecklonia cava. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2004, 27, 544–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, N.Y.; Eom, T.K.; Kim, M.M.; Kim, S.K. Inhibitory effect of phlorotannins isolated from Ecklonia cava on mushroom tyrosinase activity and melanin formation in mouse B16F10 melanoma cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 4124–4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Guo, R.; Bao, B.; Wu, W. Progress in bioactivities of phlorotannins from Sargassumi. Med. Res. 2018, 2018, 180001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.Y.; Lee, B.J.; Je, J.Y.; Kang, Y.M.; Kim, Y.M.; Cho, Y.S. GABA-enriched fermented Laminaria japonica protects against alcoholic hepatotoxicity in sprague-dawley rats. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2011, 14, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, S.H.; Kim, Y.M.; Kim, S.K. Antimicrobial effect of phlorotannins from marine brown algae. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012, 50, 3251–3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Abu-Ghannam, N. Recent developments in the application of seaweeds or seaweed extracts as a means for enhancing the safety and quality attributes of foods. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2011, 12, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijesinghe, W.A.J.P.; Ko, S.C.; Jeon, Y.J. Effect of phlorotannins isolated from Ecklonia cava on angiotensin I-Converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory activity. Nutr. Res. Pract. 2011, 5, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagayama, K.; Iwamura, Y.; Shibata, T.; Hirayama, I.; Nakamura, T. Bactericidal activity of phlorotannins from the brown alga Ecklonia kurome. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2002, 50, 889–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugiura, Y.; Matsuda, K.; Yamada, Y.; Nishikawa, M.; Shioya, K.; Katsuzaki, H.; Imai, K.; Amano, H. Isolation of a new anti-allergic phlorotannin, phlorofucofuroeckol-b, from an edible brown alga, Eisenia arborea. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2006, 70, 2807–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Qian, Z.J.; Li, Y.; Kim, M.M.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, S.K. Antioxidant effects of phlorotannins isolated from Ishige okamurae in free radical mediated oxidative systems. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 7001–7009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, A.M.; O’Callaghan, Y.C.; O’Grady, M.N.; Queguineur, B.; Hanniffy, D.; Troy, D.J.; Kerry, J.P.; O’Brien, N.M. In vitro and cellular antioxidant activities of seaweed extracts prepared from five brown seaweeds harvested in spring from the West Coast of Ireland. Food Chem. 2011, 126, 1064–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turck, D.; Bresson, J.L.; Burlingame, B.; Dean, T.; Fairweather-Tait, S.; Heinonen, M.; Hirsch-Ernst, K.I.; Mangelsdorf, I.; McArdle, H.J.; Naska, A.; et al. Safety of Ecklonia cava phlorotannins as a novel food pursuant to Regulation (EC) No 258/97. EFSA J. 2017, 15, 5003. [Google Scholar]

- Catarino, M.D.; Silva, A.M.S.; Mateus, N.; Cardoso, S.M. Optimization of phlorotannins extraction from Fucus vesiculosus and evaluation of their potential to prevent metabolic disorders. Mar. Drugs. 2019, 17, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, L.; Theodoridou, K.; Sheldrake, G.N.; Walsh, P.J. A critical review of analytical methods used for the chemical characterisation and quantification of phlorotannin compounds in brown seaweeds. Phytochem. Anal. 2019, 30, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imbs, T.I.; Zvyagintseva, T.N. Phlorotannins are polyphenolic metabolites of brown algae. Russ. J. Mar. Biol. 2018, 44, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Zhang, W.; Smid, S.D. Phlorotannins: A review on biosynthesis, chemistry and bioactivity. Food Biosci. 2021, 39, 100832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, T.P.; Ramos, A.A.; Ferreira, J.; Azqueta, A.; Rocha, E. Bioactive compounds from seaweed with anti-leukemic activity: A mini-review on carotenoids and phlorotannins. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2020, 20, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanjeewa, K.K.A.; Kim, E.A.; Son, K.T.; Jeon, Y.J. Bioactive properties and potentials cosmeceutical applications of phlorotannins isolated from brown seaweeds: A review. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2016, 162, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, T.; Ahn, M.; Hyun, J.W.; Kim, S.H.; Moon, C. Antioxidant marine algae phlorotannins and radioprotection: A review of experimental evidence. Acta Histochem. 2014, 116, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijesekara, I.; Yoon, N.Y.; Kim, S.K. Phlorotannins from Ecklonia cava (Phaeophyceae): Biological activities and potential health benefits. Biofactors 2010, 36, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, I.J.H.; Castañeda, H.G.T. Preparation and chromatographic analysis of phlorotannins. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2013, 51, 825–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glombitza, K.W.; Vogels, H.P. Antibiotics from Algae. XXXV. phlorotannins from Ecklonia maxima. Planta Med. 1985, 4, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keusgen, M.; Falk, M.; Walter, J.A.; Glombitza, K.W. A Phloroglucinol derivative from the brown alga Sargassum spinuligerum. Phytochemistry 1997, 46, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, M.; Glombitza, K.W.; Eckhard, G. Phlorotannins of phaeophycea Laminaria ochroleuca. Phytochemistry 1980, 19, 1821–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parys, S.; Kehraus, S.; Krick, A.; Glombitza, K.W.; Carmeli, S.; Klimo, K.; Gerhäuser, C.; König, G.M. In vitro chemopreventive potential of fucophlorethols from the brown alga Fucus vesiculosus L. by anti-oxidant activity and inhibition of selected cytochrome P450 enzymes. Phytochemistry 2010, 71, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quéguineur, B.; Goya, L.; Ramos, S.; Martín, M.A.; Mateos, R.; Guiry, M.D.; Bravo, L. Effect of phlorotannin-rich extracts of Ascophyllum nodosum and Himanthalia elongata (phaeophyceae) on cellular oxidative markers in human HepG2 cells. J. Appl. Phycol. 2013, 25, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, A.X.; Piao, M.J.; Hyun, Y.J.; Kang, K.A.; Fernando, P.D.S.M.; Cho, S.J.; Ahn, M.J.; Hyun, J.W. Diphlorethohydroxycarmalol attenuates fine particulate matter-induced subcellular skin dysfunction. Mar. Drugs. 2019, 17, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagayama, K.; Shibata, T.; Fujimoto, K.; Honjo, T.; Nakamura, T. Algicidal effect of phlorotannins from the brown alga Ecklonia kurome on red tide microalgae. Aquaculture 2003, 218, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rengasamy, K.R.R.; Kulkarni, M.G.; Stirk, W.A.; Staden, J.V. Eckol—A new plant growth stimulant from the brown seaweed Ecklonia maxima. J. Appl. Phycol. 2014, 27, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.Y.; Kwon, E.H.; Choi, J.S.; Hong, S.Y.; Shin, H.W.; Hong, Y.K. Antifouling activity of seaweed extracts on the green alga Enteromorpha prolifera and the mussel Mytilus edulis. J. Appl. Phycol. 2001, 13, 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.D.; Choi, J.S. Larvicidal effects of korean seaweed extracts on brine shrimp Artemia salina. J. Anim. Plant. Sci. 2017, 27, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, S.C.K.; Qian, P.Y. Phlorotannins and related compounds as larval settlement inhibitors of the tube-building polychaete Hydroides elegans. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1997, 159, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.; Terada, M.; Shin, H.C. Single dose oral toxicity and 4-weeks repeated oral toxicity studies of Ecklonia cava extract. Seikatsu Eisei 2008, 52, 282–289. [Google Scholar]

- Zaragozá, M.C.; López, D.; Sáiz, M.P.; Poquet, M.; Pérez, J.; Puig-Parellada, P.; Màrmol, F.; Simonetti, P.; Gardana, C.; Lerat, Y.; et al. Toxicity and antioxidant activity in vitro and in vivo of two Fucus vesiculosus extracts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 7773–7780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Yoon, M.; Kim, J.; Cho, S. Acute oral toxicity of phlorotannins in Beagel Dogs. Kor. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2014, 47, 356–362. [Google Scholar]

- Baldrick, F.R.; McFadden, K.; Ibars, M.; Sung, C.; Moffatt, T.; Megarry, K.; Thomas, K.; Mitchell, P.; Wallace, J.M.W.; Pourshahidi, L.K.; et al. Impact of a (poly)phenol-rich extract from the brown algae Ascophyllum nodosum on DNA damage and antioxidant activity in an overweight or obese population: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 108, 688–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, M.E.; Couture, P.; Lamarche, B. A randomised crossover placebo-controlled trial investigating the effect of brown seaweed (Ascophyllum nodosum and Fucus vesiculosus) on postchallenge plasma glucose and insulin levels in men and women. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2011, 36, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.C.; Kim, S.H.; Park, Y.; Lee, B.H.; Hwang, H.J. Effects of 12-week oral supplementation of Ecklonia cava polyphenols on anthropometric and blood lipid parameters in overweight korean individuals: A double-blind randomized clinical trial. Phytother. Res. 2012, 26, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Qian, Z.J.; Kim, M.M.; Kim, S.K. Cytotoxic activities of phlorethol and fucophlorethol derivatives isolated from Laminariaceae Ecklonia cava. J. Food Biochem. 2011, 35, 357–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phlorotannins | Sources | Administration Method | Characteristics | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bifuhalol | Sargassum spp. and Spinuligerum spp. | 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), 13C NMR | [3,5-diacetyloxy-4-(3,4,5triacetyloxyphenoxy)phenyl] acetate | [25] |

| Dieckol | Ecklonia cava | 1H NMR, 13C NMR | Two phloroglucin units are cyclized to form diphenyl dioxygen in the dehydrogenated oligomers of three pyrogallol units | [14] |

| Difucol | Bifurcaria bifurcata | 1H NMR, 13C NMR | 2-(2,4,6-trihydroxyphenyl) benzene-1,3,5-triol | [44] |

| Dioxinodehydroeckol | Ecklonia cava | 1H NMR, 13C NMR | [1,4] benzodioxino [2,3-a] oxanthrene-1,3,6,9,11-pentayl pentaacetate | [24] |

| Eckols | Ecklonia maxima | MS 50, 1H NMR, 13C NMR | Contain a 1,4-dibenzodioxin element in their structure | [45] |

| Eckstolonol | Ecklonia cava | 1H NMR, 13C NMR | [1,4] benzodioxino [2,3-a] oxanthrene substituted by hydroxy groups at positions 1, 3, 6, 9, and 11 | [14] |

| Fucodiphloroethol G | Ecklonia cava | 1H NMR, 13C NMR | Biphenyl-2,2′,4,4′,6-pentol substituted by a 2,4-dihydroxy-6-(2,4,6-trihydroxyphenoxy)phenoxy substituent at position 6′ | [2] |

| Fucotriphlorethol A | Ecklonia cava | 1H NMR, 13C NMR | Has five units of phloroglucinol, including 12 acetyl groups. Having symmetrical substitution of two magnetically equivalent protons on each ring i.e., H-2/H-6, H-9/H-11, H15/H-17, H-21/H-23, and H-27/H-29 | [24] |

| Fuhalols | Sargassum spinuligerum | 1H NMR, 13C NMR, heteronuclear multiple bond correlation (HMBC), and mass spectral data | The end monomer unit of phlorethols has an additional hydroxyl group | [46] |

| Phlorofucofuroeckol A | Ecklonia cava | 1H NMR, 13C NMR | 1,11-di-(3,5-dihydroxyphenoxy) benzofuro(3,2-a) dibenzo(b,e) (1,4)-dioxin-2,4,8,10,14-pentaol | [2] |

| Tetrafucol A | Fucus spp. and Dictyotales spp. | 1H NMR, 13C NMR | 2-(2,4,6-trihydroxyphenyl)-4-[2,4,6-trihydroxy-3-(2,4,6-trihydroxyphenyl) phenyl] benzene-1,3,5-triol | [25] |

| Tetraplorethols A and B | Laminaria ochroleuca | Thin-layer chromatography (TLC), 1H NMR, and MS data | Ortho-, meta-, and para-oriented C–O–C oxidative phenolic couplings | [47] |

| Trifucodiphlorethol A | Ecklonia cava | 1H NMR, 13C NMR | Has six units of phloroglucinol, containing biphenyl moieties with ortho, ortho -hydroxyl groups. Having a symmetrical substitution and two magnetically equivalent protons on ring I, III, and IV, and a symmetrical structure with one fully substituted aromatic moiety (ring II) | [24] |

| Trifucotriphlorethol A | Ecklonia cava | 1H NMR, 13C NMR | Has seven units of phloroglucinol, including 18 hydroxyl groups. Having a tetraphenyl fragment (rings I–IV) with non-symmetrical nature in ring II and C-16/C-19 and C-20/C-25 phenoxy-bridges in ring III and V | [24] |

| 6,6′-bieckol | Ecklonia cava | 1H NMR, 13C NMR | 1,1′-bioxanthrene substituted by 3,5-dihydroxyphenoxy groups at position 6 and 6′ and hydroxy groups at positions 2, 2′, 4, 4′, 7, 7′, 9, and 9′, respectively | [17] |

| 7-phloroeckol | Ecklonia cava | 1H NMR, 13C NMR | The hydroxy group at position 7 is replaced by a 2,4,6-trihydroxyphenoxy group | [24] |

| Cell Lines | Extract or Chemical | Sources | Method | Concentration | Toxicity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HaCaT cells exposed to PM2.5- | Eckol | Ecklonia cava | Cells were cultured with eckol and/or PM2.5- for 24 h | 30 µM | Not toxic | [5] |

| HaCaT cells exposed to PM2.5- | Diphlorethohydroxycarmalol | Ishige okamurae | MTT (3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol 2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay and incubated for 16 h | 2.5, 5, 10, 20, and 40 µM | Not toxic | [50] |

| HaCaT cells exposed to PM10 | Dieckol | Ecklonia cava | MTT assay and incubated for 2 h at room temperature | 20–100 µg/mL | Decreased cell viability and increased PGE2 release | [11] |

| HaCaT cells exposed to PM10 | Dieckol | Ecklonia cava | MTT assay and incubated for 2 h at room temperature | 25, 50, 75, and 100 µg/mL | Had no effects on the viability of HaCaT cells | [18] |

| HaCaT cells | Dieckol | Ecklonia cava | MTT assay and incubated for 4 h | 100 µg/mL | Increased cell viability | [16] |

| HeLa cells | Eckol and dieckol | Ecklonia stolonifera | MTT assay and incubated for 4 h | 10 µg/mL | Inhibited NF-kB and AP-1 reporter activity | [3] |

| HeLa, A549, HT1080, HT-29, and MRC-5 (human normal cell line) | Dieckol | Ecklonia cava | MTT assay and incubated for 4 h | 400 µM | Not toxic on MRC-5 and had activity on tumour suppressive | [2] |

| Human colon adenocarcinoma (Caco-2) cells | Crude extract | Fucus serratus | MTT assay and incubated for 24 h | 100 µg/mL | Not toxic | [33] |

| Human fibroblast cell | Dieckol | Ecklonia cava | MTT assay and incubated for 4 h | 5, 50, and 100 μM | Increased cell viability | [12] |

| Human fibrosarcoma cell line (HT1080) | 6,6′-bieckol | Ecklonia cava | MTT assay and incubated for 4 h | 0–200 μM | Not significantly toxic and blocked tumor invasion | [22] |

| Human hepatoma HepG2 cells | Crude extract | Ascophyllum nodosum and Himanthalia elongata | Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) leakage and crystal violet assay | 0.5–50 µg/mL | Not toxic | [49] |

| B16F10 melanoma cells | Eckol | Ecklonia cava | MTT assay and incubated for 4 h | 25, 50, and 100 μM | Not toxic and inhibited tyrosinase activity and melanin synthesis | [4] |

| B16F10 melanoma cell | 7-phloroecko | Ecklonia cava | MTT assay and incubated for 4 h | 6.25–100 μM | Not toxic and inhibited melanin production | [24] |

| Human leukemia cell line (KU812) and rat basophilic leukemia cell line (RBL-2H3) | Dieckol | Ecklonia cava | MTT assay and incubated for 2 h at room temperature | 500 μM | Low toxicity | [17] |

| Rat vibrissa immortalized dermal papilla cell line | Dieckol | Ecklonia cava | MTT assay and incubated for 4 h | 100 µg/mL | Inhibited 5α-reductase activity | [13] |

| Microalgae/Seaweed/Plant | Extract or Chemical | Sources | Method | Concentration | Toxicity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chattonella antiqua | Crude extract | Ecklonia kurome | Phlorotannins were dissolved in 70% methanol and were added to 20 mL of microalgal suspensions | 20–500 mg/L | Inhibited swimming, and lost their motility | [51] |

| Cochlodinium polykrikoides | Crude extract | Ecklonia kurome | Phlorotannins were dissolved in 70% methanol and were added to 20 mL of microalgal suspensions | 20–500 mg/L | Inhibited swimming, and lost their motility | [51] |

| Enteromorpha prolifera | Crude extract | Ishige sinicola | A 1.0 mL aliquot of spore was added to the extract | 30 µg/mL | Inhibited settlement of the spore | [53] |

| Vigno mungo | Eckol and phloroglucinol | Ecklonia maxima | The seeds were planted in trays and were added eckol and phloroglucinol | 10−3–10−7 M | Increased seedling length and weight | [52] |

| Kerenia mikimotoi | Crude extract | Ecklonia kurome | Phlorotannins were dissolved in 70% methanol and were added to 20 mL of microalgal suspensions | 20–500 mg/L | Inhibited swimming, and lost their motility | [51] |

| Invertebrates | Extract or Chemical | Sources | Method | Concentration | Toxicity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artemia salina | Crude extract | Dictyota dichotoma, Ecklonia kurome, Ishige okamurae, Sargassum sagamianum, and Pachydictyon coriaceum | 50 μL of brine shrimp larvae solution (containing ca. 20 larvae) was added with extracts and determined after 2, 4 6, 12, 24, and 24 h of exposure | 0.25%, 0.5%, and 2.5% | 2.5% extract had significant larvicidal activity | [54] |

| Hydroides elegans | Crude extract | Sargassum tenerrimum | Twenty larvae were introduced into each Petri dish containing 5 mL of test solution and were incubated at 28 °C. Survivorship was determined after 48 h of incubation. | 10−4–103 ppm | EC50 at 0.526 ppm and LC50 at 13.948 ppm | [55] |

| Mytilus edulis | Crude extract | Ishige sinicola and Scytosiphon lomentaria | 10 µL seaweed extract was dripped on the foot. | 40 µg/10 µL | Inhibited the repulsive activity of the foot and strong antifouling activities | [53] |

| Portunus trituberculatus | Crude extract | Ecklonia kurome | 0.5-h exposure | 200 mg/L | No died | [51] |

| Animals | Extract or Chemical | Sources | Method | Concentration | Toxicity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seabream | Crude extract | Ecklonia kurome | 0.5-h exposure | 200 mg/L | Light side effects, and no death | [51] |

| Tiger puffer | Crude extract | Ecklonia kurome | 0.5-h exposure | 200 mg/L | Light side effects, and no death | [51] |

| Zebrafish embryo | Dieckol | Ecklonia cava | Embryos were treated with 25 mM AAPH (2,20-azobis-2-methyl-propanimidamide dihydrochloride) or co-treated with AAPH and phlorotannins for up to 120 h post-fertilization (120 hpf). | 50 μM | No conspicuous adverse effects and did not generate any heartbeat rate disturbances | [14] |

| Zebrafish | Dieckol | Ecklonia cava | Feed ad libitum with hardboiled egg yolk as a high-fat diet (HFD) once per day in the presence or absence of the indicated compounds (17–20 dpf) or vehi- cle (dimethyl sulfoxide, DMSO) for 12–15 days (17–20 dpf) for 12–15 days. | 1 and 4 μM | Reduced the levels of body lipids | [10] |

| ICR mice | Crude extract | Ecklonia kurome | Oral, free access to food and tap water for 14 days | 0, 625, 1250, 2500, 5000 mg/L | No death | [30] |

| ICR mice | Dieckol | Ecklonia cava | Oral, treatment during 11 weeks | 60 mg/kg BW/day | Reductions of final body weight and body weight gain | [10] |

| HR-1 hairless male mice | Diphlorethohydroxycarmalol | Ishige okamurae | The mouse dorsal skin was placed in continuous contact with the pads for 7 days | 200 µM and 2 mM | Inhibited lipid peroxidation, protein carbonylation, and epidermal height | [50] |

| Sprague dawley rats | Crude extract | Fucus vesiculosus | Oral, treatment during 4 weeks | 200 mg/kg/day | Lack any relevant toxic effects | [57] |

| Sprague dawley rats | Crude extract | Ecklonia cava | oral, 1 time/day for 4 weeks | 0, 222, 667, 2000 mg/kg BW | No death | [56] |

| Beagle dogs | Dieckol | Ecklonia cava | Oral, treatment during 15 days | 750 mg/kg BW | Soft stool and diarrhea | [58] |

| Participants | Extract or Chemical | Sources | Method | Concentration | Toxicity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Twenty-three participants (11 men, and 12 women) aged 19–59 years | Crude extract | Ascophyllum nodosum and Fucus vesiculosus | Oral, 1 capsule/day, treatment during 1 week | 250 mg/capsule | No side effect | [60] |

| Twenty-four participants | Dieckol | Ecklonia cava | Oral, 2 capsules/day, treatment during 1 week | 500 mg/capsule | No serious adverse effects | [20] |

| Eighty participants aged 30–65 years | Crude extract | Ascophyllum nodosum | Oral, 1 capsule/day, treatment during 8 weeks | 100 mg/capsule | No side effect | [59] |

| 107 participants (138 men, and 69 women) aged 19–55 years | Crude extract | Ecklonia cava | Oral, 1 capsule/day, treatment during 12 weeks | 72 mg/capsule and 144 mg/capsule | No side effect | [61] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Negara, B.F.S.P.; Sohn, J.H.; Kim, J.-S.; Choi, J.-S. Effects of Phlorotannins on Organisms: Focus on the Safety, Toxicity, and Availability of Phlorotannins. Foods 2021, 10, 452. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10020452

Negara BFSP, Sohn JH, Kim J-S, Choi J-S. Effects of Phlorotannins on Organisms: Focus on the Safety, Toxicity, and Availability of Phlorotannins. Foods. 2021; 10(2):452. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10020452

Chicago/Turabian StyleNegara, Bertoka Fajar Surya Perwira, Jae Hak Sohn, Jin-Soo Kim, and Jae-Suk Choi. 2021. "Effects of Phlorotannins on Organisms: Focus on the Safety, Toxicity, and Availability of Phlorotannins" Foods 10, no. 2: 452. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10020452

APA StyleNegara, B. F. S. P., Sohn, J. H., Kim, J.-S., & Choi, J.-S. (2021). Effects of Phlorotannins on Organisms: Focus on the Safety, Toxicity, and Availability of Phlorotannins. Foods, 10(2), 452. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10020452