Abstract

Recently significant initiatives have been launched for the dissemination of Open Access as part of the Open Science movement. Nevertheless, two other major pillars of Open Science such as Open Research Data (ORD) and Open Peer Review (OPR) are still in an early stage of development among the communities of researchers and stakeholders. The present study sought to unveil the perceptions of a medical and health sciences community about these issues. Through the investigation of researchers‘ attitudes, valuable conclusions can be drawn, especially in the field of medicine and health sciences, where an explosive growth of scientific publishing exists. A quantitative survey was conducted based on a structured questionnaire, with 179 valid responses. The participants in the survey agreed with the Open Peer Review principles. However, they ignored basic terms like FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) and appeared incentivized to permit the exploitation of their data. Regarding Open Peer Review (OPR), participants expressed their agreement, implying their support for a trustworthy evaluation system. Conclusively, researchers need to receive proper training for both Open Research Data principles and Open Peer Review processes which combined with a reformed evaluation system will enable them to take full advantage of the opportunities that arise from the new scholarly publishing and communication landscape.

1. Introduction

It is an unquestionable fact that new knowledge is created through global interdisciplinary collaborations. Therefore, the European Commission has made “Open Science” a high priority goal, along with “Open Innovation” and “Open to the World” initiatives, to keep European Union states competitive at the global level [1].

Open Science gives the opportunity through remarkable technological advantages to archive, curate and disseminate interdisciplinary research results across the globe in terms of greater efficiency, replicability, reproducibility and transparency. It has to be clarified that Open Science is not a dogma but a “movement which aims to make scientific research, data and dissemination accessible to all levels of an inquiring society” [2].

The “Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities” in 2003 [3] is regarded as the main reference for the access and sharing of scientific results in the digital age. Previous definitions of Open Access were related to free access to peer-reviewed literature (Budapest Open Access Initiative, 2002 [4] and Bethesda Statement on Open Access Publishing, 2003 [5]), whereas the “Berlin Declaration” for the first time, considers not only articles but also “raw data and metadata, source materials, digital representations of pictorial and graphical materials and scholarly multimedia material” to be openly accessible and reusable. Starting with the Berlin Declaration, many initiatives have taken place to promote Open Science such as the EU‘s Open Science policy [6].

Although significant initiatives have been launched and substantial efforts have been made for the implementation and dissemination of Open Access, two main components of Open Science, among others (e.g., Open Preprints, Open Source etc.), namely Open Research Data (ORD) and Open Peer Review (OPR) are still in an early stage of development in the communities of researchers, funders and information scientists [7].

Open Research Data (ORD) are classified in various categories, such as observational, experimental, computer simulation data etc. Also, they can be found in many forms such as documents, laboratory notebooks, questionnaires, images, audio and video clips, samples, specimens, data files, etc. [8]. In the current data-intensive landscape, sharing research data is a matter of considerable significance. Sharing scientific data will speed up replicability, reproducibility, and improve the transparency of the research process and assessment accordingly, promoting at the same time the public access to the results [9,10]. It is worth mentioning that funders such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have officially supported data sharing as the premium medium to translate research results into knowledge, products and procedures, for the benefit of human health since 2003 [11].

In this context, FAIR data principles were published a few years ago to describe how research data should be shared. FAIR stands for Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable and these are the features that research data should possess when shared, in terms of the “as open as possible, as closed as necessary” philosophy [9,12]. The success of FAIR is substantially dependent on cultural changes which will eliminate negative behaviours such as misusing or misinterpreting of data and on significant changes to researchers existing system of incentives and rewards [13]. It is essential to mention that a report was released recently by the FAIR in Practice Task Force of the European Open Science Cloud FAIR Working Group [14] as a follow up on the 2018 report [12] in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. According to this report, FAIR practices help significantly to expedite the needed research processes to fight this new disease. However, more acceleration would be possible had FAIR principles been more broadly implemented [14].

The second major pillar of Open Science is Open Peer Review (OPR) which has neither a standardized definition nor an agreed schema of its features and implementations. It is an umbrella term for several overlapping ways or attributes that peer review models can adapt in line with the aims of Open Science (e.g., open identities, open reports, open participation, open interaction) [15]. An Open Peer Review process is a valuable addition to the scientific publishing landscape because transparency is as important as openness [16]. By adopting openness of data sets, code, materials, processes, and any other resources, transparency is significantly improved, as other researchers are able to fully evaluate the basis for any research findings, and verify or reproduce the work. Moreover, it is not just a matter of making reviews publicly available, but bringing the choices of editors, reviewers, editorial decisions, and author‘s responses also into the public space allowing a creative interaction [16].

In this context, “mega journals” such as PLoS were among the early adopters of the Open Access movement by giving emphasis on the rapid publication of research, post-publication evaluation through article-level statistics and by implementing Open Peer Review techniques (e.g., open reports) [17]. Additionally, to decouple peer review process from journals in general and its functions, inbuilt systems for the post-publication peer review were created (e.g., F1000 Research) [18].

Apart from publishers‘ initiatives, there is also substantial research activity on supporting Open Peer Review application. For example, Artificial Intelligence could be a valuable tool to the formation of a new and more efficient open peer review process along with further diversity in the reviewer pool [19]. Moreover, some suggest that peer review processes adopt the characteristics of open code social platforms (e.g., Wikipedia, Amazon, Reddit) for achieving democratization. At the same time, the implementation of “blockchain” technology is discussed for maximizing reviewers‘ rewards [18]. Additionally, an interactive open access peer review model can be easily integrated into both new and existing scientific journals. Repositories such as arXiv.org have already adopted an interactive discussion platform for efficient review and open discussion [20,21]. Another example of implementing Open Peer Review attributes is the Transparent Peer Review model, applied by Wiley in more than 60 journals with the use of ScholarOne and Publons platforms. Remarkably, more than 87% of authors in these journals have chosen this approach for their articles [22].

Attempting to promote further the concepts of openness for both data and review process, it is necessary to first identify the scientific communities‘perceptions about these topics. In particular, librarians and information scientists could develop more effective strategies for promoting Open Research Data (ORD) and Open Peer Review (OPR) in interdisciplinary communities only if they are aware of the scientists‘ attitudes.

In this context, the present research aims to investigate the viewpoints of a representative medical and health sciences community towards Open Peer Review (OPR). Also, aims to identify if Open Peer Review (OPR) is considered a trustworthy peer review process, highlighting the fact that it is most prevelant in medical disciplines [23]. Furthermore, this study attempts to unveil the degree of knowledge of medical and health professionals about Open Research Data (ORD) and of their agreement on sharing their content as it is also explored in previous studies [24].

2. Literature Review

Even though data sharing offers great potential for scientific progress by reproducing study results and by allowing the reuse of data, scientists hesitate to make their files available in public. The study of Zuiderwijk et al. [25] provides a systematical review of 32 open data studies on individual researchers‘ drivers and inhibitors for sharing and using Open Research Data (ORD). The upcoming paragraphs attempt to identify the most common inhibitors that result in low rates of data sharing among researchers, focusing on the medical community.

Medical research is reported to have a low data sharing culture, probably related to the fact that it works with individual-related data [26]. Health data (e.g., the use of human material) demand for special considerations such as privacy protecting principles and protection regulations [27]. Even when complying with medical data protection policies (e.g., Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)) [28], there is always the risk of data re-identification [24,29], making researchers more reluctant to share their data openly. The study of Tenopir et al. [30] also revealed that there is a strong influence of the researcher‘s age on the willingness to share data. In particular, junior scientists are less likely to make their data available to others compared with the senior ones (over 50 years old), who are willing to share their data. This behavior can be explained by high competition, especially among non-tenured researchers. This study also points out the different disciplinary practices. Specifically, in medicine and health sciences, most researchers are reticent regarding the accessibility of their own data. It is also found that academics are strongly against the use of their work for commercial gain without their prior knowledge or permission, even when they receive credit as the original authors [31]. Specifically, Savage and Vicker reported that only one author among the authors of ten articles published in the PLoS Medicine or PLoS Clinical Trials journals allowed access to the research data mostly because of their personal sensitive nature [32]. In addition, the community of atmospheric and life sciences researchers are more willing to share knowledge, proven by the fact that very quickly they adopted common standards for organizing and exchanging their research data [30].

Additionally, researchers express the urge to have control, regarding access and use of the data that accompany publications. They also report a lack of sufficient formal recognition in comparison to the journal articles and lack of professional reward for sharing [26,33].

It is reported that researchers often do not share their data, because they worry about people misusing and misinterpreting them [34,35,36,37]. Moreover, sharing data can be time-consuming (e.g., preparing a data set) and researchers are often unaware of the existence of repositories that offer related services. Researchers have not trained adequately for managing and sharing data [38]. The extra working load along with teaching and administrative obligations, the disciplinary norm, the unclear career benefits and the risks that may occur could significantly have a negative impact on researchers‘ attitudes towards data sharing [24,39]. Only scientists who exclusively conduct research are more likely to share their data because of the time privilege [25,26].

Nevertheless, most of the medical scientists consider as a fair exchange for others to use their data under certain conditions: (a) if there is opportunity to collaborate on the project, (b) if results based on the data could only be disseminated with the data provider‘s approval, (c) if at least part of the costs of data acquisition, retrieval or provision must be recovered or (d) if legal permission for data use is obtained [30].

Due to the nature of medical data (e.g., huge volume and breadth, privacy issues) and the need for an efficient process, it is vital to extend FAIR to FAIR-Health principles, as proposed by Holub et al. [27] and introduce a positive framework of incentives aimed at the health communities.

As far as the peer review process is concerned, it was introduced by the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1731 [40] and journals started using it formally, after 1960 [19]. It has played a decisive role and has been so well established that it is challenging to conceive any future change [41]. The two traditional forms of peer review (single and double blind) and lately, the Open Peer Review model are the principal evolved forms [18], which all aim to achieve the maximum transparency. Focusing more on the health and medical disciplines, the PEER D4 study reports that researchers from these fields have the highest number of articles compared with other researchers and always choose peer-reviewed journals [42]. Moreover, it is certified that scientists in medicine and health science decide to publish their papers in journals that implement a formal and trustworthy peer review process, regardless the content access model (e.g., OA and non-OA) [43].

A large number of studies on single and double-blind peer review models demonstrate that they are rarely impartial or evidence-based and with high levels of complexity [44,45,46]. Reported biases that concern the gender, the nationality, the affiliation and the language of authors [44,47] confirm that there is no longer the question of whether the traditional peer review is impartial, but what the probable causes and solutions are [46]. The Open Peer Review (OPR) could contribute positively to improve transparency by highlighting such incidents of inappropriate reviewers‘ behavior and managing or even resolving misconduct that arises from reviewer’s identification. Transparency is an ultimate goal for an evaluation framework which can function as a mechanism of accountability, i.e., almost absent at the traditional models [46]. Moreover, Open Peer Review (OPR) can reinforce innovative efforts and minimize the negative aspects of the peer review. Presently, the increasing number of produced papers by researchers resulted in higher rejection rates and multiple reviews of the same content by different journals (“review process” overload), which may be one of the reasons for the evaluation reports reduced quality [48].

Regarding the above discussion, the crucial question that arises is if Open Peer Review could actually be the alternative path that will help research community to overcome or minimize the negative aspects of the existing assessment framework. For example, Sueur et al. [49] suggest that a more open evaluation model could improve the educational value of peer review, increase the constructive criticism that encourages researchers, and reduce pride and prejudice in editorial processes. Besides, studies already showed that articles with Open Peer Review reports and Open Research Data policy could be expected to have significantly greater citation counts compared to articles with closed peer review history and closed research data [50,51]. Nevertheless, there is no longitudinal evidence that new evaluation models such as Open Peer Review (OPR) are superior to the traditional ones at either a population or system-wide level [46]. Open Peer Review (OPR) cannot be applicable under all circumstances since there is no standard procedure for its main functions such as open reports, open identities, open participation etc. [52]. Additionally, it has to be clarified that although Open Peer Review (OPR) provides incentives for a more transparent and collaborative evaluation framework, it is not able yet to completely prevent undesirable behavior, misconduct incidents or eliminate automatically all identity-related biases [53,54].

The present paper aims to contribute to the ongoing discussion for Open Research Data (ORD) and Open Peer Review (OPR) by providing the viewpoints of the medical and health sciences community in Greece.

3. Materials and Methods

For investigating the attitude of medical and health sciences community on issues about Open Research Data (ORD) and Open Peer Review (OPR), a quantitative survey was conducted based on a structured questionnaire, which is divided into three parts, namely FAIR principles awareness and Open Research Data-Open Peer Review related questions (See Appendix A). It was considered necessary to include a brief, intelligible definition before each part to ensure the best possible comprehension of the questions and avoid misunderstandings.

The questionnaire was sent electronically through the Lime Survey platform to 415 health professionals, affiliated with the General Hospital of Athens “Hippokration”. They were selected from the contact list of the hospital library. To save time and to avoid survey fatigue with excessive amount of requested information, it was decided to check for publication activity based on Google Scholar, only the participants that provided full responses. 179 out of 215 of the participants that provided full responses, appeared as authors in scientific publications based on the information provided by Google Scholar. The 179 valid participants in the questionnaire (see Table 1) were from 42 academic doctors, 88 doctors in the National Health System, 17 nursing and paramedical staff members and 32 postgraduate medical students and health researchers (Other). Based on Google Scholar search results per participant, the average number of publications per category is presented in the table that follows.

Table 1.

Publication history information based on Google Scholar results per participants’ category.

All of them, as explained above, have an active publication history in scientific journals. They all agreed to participate in a series of surveys, which included topics related to scholarly publishing as the ones presented in this paper. As soon as the completed questionnaires were gathered in January 2020, the data processing began. Apart from the professional category, other demographic characteristics were the years of professional experience and gender.

The types of questions were based on the psychometric Likert scale, which is often used in similar surveys, for the evaluation of population attitude or opinion. Participants could choose from 4 scales instead of 5, in an attempt to achieve more concrete results by preventing them from taking the easy way of neutrality. Similar surveys [55,56] inspired the content of the questionnaire.

4. Results

In the first part of the survey (Part 1) the participants were asked if they are familiar with the FAIR principles. It is noted that before completing the survey, participants were presented with the definitions of the key terms contained in the questions (e.g., OA, FAIR, OPR, ORD etc.) As it is depicted in the following table (Table 2), most of the population (78.2%) was unaware of FAIR principles, before the survey. The highest level of familiarization with FAIR principles was found among academic doctors (33.3%), while nursing and paramedical staff were the most unaware (1 out of 17 was aware of FAIR principles before the survey).

Table 2.

Part 1-How familiar you were with the FAIR principles before the survey.

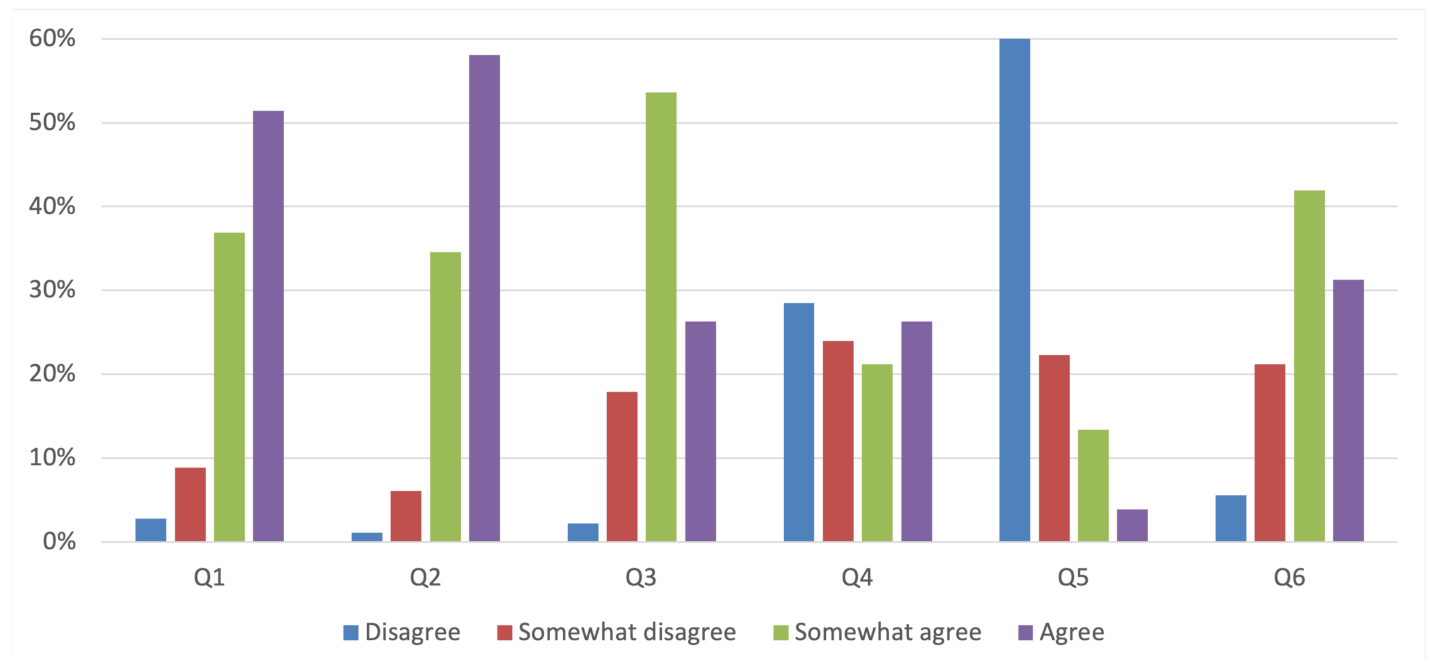

In Part 2 of the survey, medical and health scientists were asked to define the level of their agreement (1-Disagree, 2-Somewhat disagree, 3-Somewhat agree, 4-Agree) regarding specific Open Research Data issues through six questions. For each topic (Q1 to Q6) the mean, the standard deviation and the percentages values for all participants and per gender, professional category and age are presented in Table 3a, Table 3b, Table 4a, Table 4b, Table 5a and Table 5b. Also, in Figure 1 percentages values for all responses per topic are depicted in a bar chart. 88.3% of the participants agree or somewhat agree with the statement that publication should include related research data files with open or closed access (Table 3b/All responses-Q1). They also believe (92.7%-agree or somewhat agree) that Open Research Data (ORD) will significantly contribute to research promotion and science progress (Table 3b/All responses-Q2). They recognize that FAIR principles are difficult to implement because of the lack of proper training and support (79.9%-agree or somewhat agree-Table 3b/All responses-Q3). Only 47.5% of the participants agree or somewhat agree with the exploitation of their own data from others, in a non-commercial way, with the proper credits attribution (Table 3b/All responses-Q4). Moreover, participants do not agree with the exploitation of their own data, by third parties, for commercial purposes (only 17.3% agree or somewhat agree-Table 3b/All responses-Q5). Finally, most of the participants’ viewpoints (73.2%-agree or somewhat agree-Table 3b/All responses-Q6) align with the argument that FAIR principles are more difficult to apply in disciplines such as medical sciences (e.g., due to personal information contained to medical research data).

Table 3.

(a) Define the level of agreement with the following topics regarding Open Research Data-Mean and Standard Deviation per topic (Part 2, Q1 to Q6, All–Male–Female); (b) Define the level of agreement with the following topics regarding Open Research Data-Percentages per topic (Part 2, Q1 to Q6, All–Male–Female).

Table 4.

(a) Define the level of agreement with the following topics regarding Open Research Data-Percentages per topic-Mean and Standard Deviation per topic [Part 2, Q1 to Q6, professional category: Academic Doctors (Acad.), NHS Doctors (NHS), Nursing and Paramedical Staff (N-P), Other]; (b) Define the level of agreement with the following topics regarding Open Research Data-Percentages per topic [Part 2, Q1 to Q6, professional category: Academic Doctors (Acad.), NHS Doctors (NHS), Nursing and Paramedical Staff (N-P), Other].

Table 5.

(a) Define the level of agreement with the following topics regarding Open Research Data-Percentages per topic-Mean and Standard Deviation per topic (Part 2, Q1 to Q6, years of experience: 1–10y, 10–20y, >20y); (b) Define the level of agreement with the following topics regarding Open Research Data-Percentages per topic-Percentages per topic (Part 2, Q1 to Q6, years of experience: 1–10y, 10–20y, >20y).

Figure 1.

Define the level of agreement with the following topics regarding Open Research Data (Part 2, Q1 to Q6, All responses).

Comparing the overall results of Part 2 (Table 3b/All responses) with the demographic characteristics of the population sample such as gender (Table 3b/Male/Female), professional category (Table 4b) and years of experience (Table 5b), some noteworthy differences were observed. Specifically, as it is shown in Table 3b, males are more positive (58%-agree or somewhat agree-Table 3b/Male-Q4) than females (34.2%-agree or somewhat agree-Table 3b/Female-Q4) with the idea of the exploitation of their data.

In Table 4a,b where responses are presented according to the professional category of the participants, the majority of academic doctors (54.7%-Table 4b/Acad. Doctor-Q4) agreed with the possibility that their data could be exploited by third parties for non-commercial use and by receiving credit first. In contrast, doctors in National Health System, nursing, paramedical staff and other medical researchers mostly disagree.

Finally, in Table 5a,b, responses are depicted according to the years of experience of the sample population (mean values, standard deviation and percentages). It is observed that younger scientists with 1–10 years of experience disagree or somewhat disagree more (58.6%-Table 5b/1–10y-Q4) in comparison with the ones of 10–20 (51.8%-Table 5b/10–20y-Q4) and >20 (50.7%-Table 5b/>20-Q4) years of experience regarding the exploitation of their data by third parties for non-commercial use and by receiving the credit first.

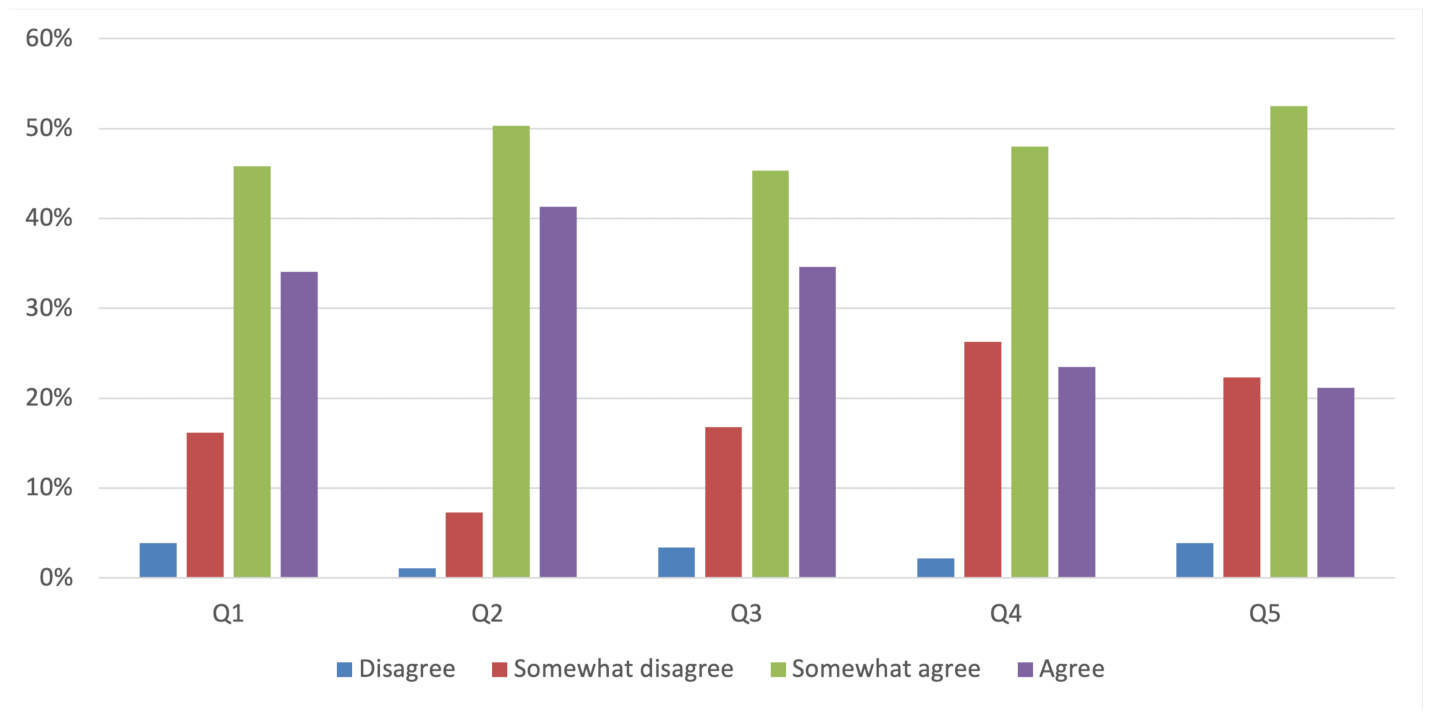

In Part 3 medical and health scientists were asked to define their position (1-Disagree, 2-Somewhat disagree, 3-Somewhat agree, 4-Agree) regarding Open Peer Review potentials through five questions (topics Q1 to Q5). For each topic the mean, the standard deviation and the percentages values for all participants and per gender, professional category and age are presented in Table 6a,b, Table 7a,b and Table 8a,b. Also, in Figure 2 percentages values for all responses, per topic are depicted in a bar chart. In particular, participants seem to agree or somewhat agree (79.9% Table 6b/All responses-Q1) with the potential to submit a scientific article to a journal which follows Open Peer Review system and its multiple functions such as open reviewer’s identities, open preprints, open participation etc. Moreover, the participants adopt the same positive position (91.6%-Table 6b/All responses-Q2) towards the potential to publish their work in a journal which aligns with Open Peer Review (OPR) and the whole reviewer‘s report with the author‘s response would be included in the final publication. The sample population also agreed or somewhat agreed (79.9%-Table 6b/All responses-Q3), expressing their willingness to review an article published on a journal following Open Peer Review (OPR) knowing that their identity and report would be published in the final publication. Additionally, the participants think positively (71.5%-Table 6b/All responses-Q4) of submitting their work to journals such as PLoS which publish articles fast based on the technical soundness of research without any judgement on its novelty. Medical and health scientists also agreed or somewhat agreed (73.7%-Table 6b/All responses-Q5) with the idea of submitting their work to platforms such as F1000 Research, where fast post-publication peer review takes place after a basic formal check done by selected experts and readers.

Table 6.

(a) Define your position regarding Open Peer Review potentials-Mean and Standard Deviation per topic (Part 3, Q1 to Q5, All-Male-Female); (b) Define your position regarding Open Peer Review potentials-Percentages per topic (Part 3, Q1 to Q5, All-Male-Female).

Table 7.

(a) Define your position regarding Open Peer Review potentials-Mean and Standard Deviation per topic [Part 3, Q1 to Q5, professional category: Academic Doctors (Acad.), NHS Doctors (NHS), Nursing and Paramedical Staff (N-P), Other]; (b) Define your position regarding Open Peer Review potentials-Percentages per topic [Part 3, Q1 to Q5, professional category: Academic Doctors (Acad.), NHS Doctors (NHS), Nursing and Paramedical Staff (N-P), Other].

Table 8.

(a) Define your position regarding Open Peer Review potentials-Mean and Standard Deviation per topic (Part 3, Q1 to Q5, years of experience: 1–10y, 10–20y, >20y); (b) Define your position regarding Open Peer Review potentials-Percentages per topic (Part 3, Q1 to Q5, years of experience: 1–10y, 10–20y, >20y).

Figure 2.

Define your position regarding Open Peer Review potentials (Part 3, Q1 to Q5, All responses).

Comparing the overall results (Table 6b/All) with the demographic data of the present research such as gender (Table 6b/Male/Female), professional category (Table 7b) and years of experience (Table 8b) no remarkable differences were observed. It seems that medical and health sciences community is highly active in Open Peer Review (OPR) and its potentials.

The above results lead to the conclusion that most of the participants expressed a positive attitude towards ORD but a low level of personal knowledge about them. Regarding Open Peer Review model and its potentials, most of the population sample reacted again positively. However, the evaluation procedures and mechanisms are not clear yet or have not been described in a uniform or standardized way. A full analysis and discussion of the results will follow in the upcoming sections.

5. Discussion

Going deeper into the interpretation of the results, the majority of the population sample, even though they agreed with the beneficial contribution of data sharing to research promotion and science progress, strongly expressed a clear opposition against the exploitation of their data by third parties, commercially and non-commercially, even when credit attribution applies [31]. The unwillingness to share their own data, among other reasons presented in the discussion, could also be justified by participants‘ positive response to the statement that in medicine and health sciences, it is hard to implement Open Research Data principles (e.g., FAIR), due to individual-related data [26]. Additionally, younger participants, especially female with 1–10 years of experience compared to their older colleagues, are less likely to share their research data as it is also confirmed in an earlier study [30]. The results of the present study also point out the lack of proper training and support regarding the implementation of FAIR principles in data sharing process which is also reported in other studies [24,39] revealing the absence of the necessary skills on how to share data along with the limited awareness of the available repositories or data preparation standards.

Regarding Open Peer Review (OPR) and its potentials, the majority of the participants expressed their willingness to publish their papers’ peer review reports and be reviewers in journals which follow Open Peer Review system, aligning with the content and results of other studies [23,57]. The outcomes of the present research also reinforce, as it is already mentioned in the introduction, the fact that Open Peer Review adoption is most prevalent in medical disciplines and agree with the steady growth in Open Peer Review adoption, which has been observed since 2001 [23]. Even though in the present study the participants mainly agreed to use Open Peer Review and its potentials, it is quite questionable if the participants actually have realized its full potentials, which is also confirmed in Patel et al. [58] study. Additionally, the majority of the respondents appear to consider peer review a process of validation, as reported in other studies [58,59] since they highly rated publication choices such as PLoS and F1000Research, where the first priority is the technical soundness and the reliability of the research. This result could also be related to the fact that medical scientists care mostly about the trustworthy peer review process, regardless of the content access model (e.g., OA and non-OA) [43].

6. Restrictions–Future Suggestions

It is important to clarify that the present survey focuses on medicine and health sciences discipline because of its explosive pace of publishing and a great urge for scientific communication. Additionally, although the target group of the survey is limited to the Greek medical community, its methodology could apply to other scientific fields and probably to different countries with the necessary adjustments. Moreover, the results of the survey are considered a valuable attribution towards the development of a sufficient strategy for the dissemination of Open Science principles among the members of the medical community. The examination of the similarities and differences of researchers‘ viewpoints towards Open Research Data (ORD) and Open Peer Review (OPR), from diverse scientific fields, is our target for any future activities.

7. Conclusions

As already stated in the results section, it becomes apparent that the participants of the medicine and health care community are positive towards Open Research Data initiatives regarding the beneficial contribution to the conduct of research and the advancement of science in general. On the contrary, they are not familiar with basic terms of Open Research Data (ORD), such as FAIR principles and they are opposed to any exploitation of their research data for commercial and non-commercial use. In addition, especially for health sciences, it is also related to the personal (sensitive) character of the medical research data, which demands compliance with medical data protection policies, and it is reflected as well as in participants’ responses in the present survey. These outcomes also imply lack of knowledge about the benefits of data sharing process and the re-usability positive potentials, indicating at the same time an apparent absence of proper training about subject open repositories, research data management, data anonymization techniques etc.

As far as the Open Peer Review (OPR) is concerned, the participants seem to agree with the new potentials such as open reports and post peer review process, but it is not very certain whether they have fully understood in depth the functions of the Open Peer Review model. Nevertheless, researchers conceive peer review as a highly significant research validation mechanism through which they will obtain reputation and promotion [60,61] and seek transparency in the research publishing process. Therefore, as it is shown in survey‘s results, they are willing to support every effort that targets a highly trustworthy peer review system.

One of the most important conclusions is that researchers need to receive proper training for both Open Research Data principles and Open Peer Review processes. Librarians, information scientists, publishers, and other stakeholders should undertake initiatives such as data services, workflows, and consultations that are tailored to the needs and the particular requirements of each scientific community. The proper education about the key components of Open Science movement, in conjunction with the tenure-centred evaluation system reformation, will enable researchers to take full advantage of the opportunities that arise from the new scholarly publishing and communication landscape.

Author Contributions

All authors have contributed equally. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the Information Management Research Lab, Department of Archival, Library and Information Studies, University of West Attica.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FAIR | Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable |

| NHS | National Health System |

| OA | Open Access |

| ORD | Open Research Data |

| OPR | Open Peer Review |

| PLoS | Public Library of Science |

Appendix A. Questionnaire

Personal Information

Q1—Please state your professional category.

Answer options Option 1: Academic Doctor, Option 2: NHS Doctor, Option 3: Nursing and Paramedical Staff, Option 4: Other

Q2—Please specify years of experience.

Answer options: Option 1: 1–10y, Option 2: 10–20y, Option 3: >20y

Q3—Please specify your gender.

Answer options: Option 1: Male, Option 2: Female

Part 1—Are you familiar with the FAIR principles;

Answer options: Option 1: Yes, Option 2: No

Part 2—Define the level of agreement with the following topics regarding Open Research Data

Q1—Articles submitted for publication should include related research data files with open or closed access.

Q2—Open Access to Research Data related with published articles will significantly contribute to research promotion and science progress.

Q3—Researchers are unable to follow/apply FAIR principles due to lack of proper or appropriate training and support.

Q4—Would you share your research data for exploitation from third parties allowing them to remix, adapt, and build upon your work non-commercially, as long as they credit you;

Q5—Would you share your research data for exploitation from third parties allowing them to remix, adapt, and build upon your work even for commercial purposes, as long as they credit you;

Q6—Do you consider more difficult to implemented FAIR principles in disciplines such as medical sciences (e.g., due to personal information contained to medical research data);

Answer options: Option 1: Disagree, Option 2: Somewhat disagree, Option 3: Somewhat agree, Option 4: Agree.

Part 3—Define your position regarding OPR potentials.

Q1—Would you submit a scientific article to a journal following OPR where the reviewer‘s identities would be revealed to authors and vice versa and included in the final publication;

Q2—Would you submit a scientific article at a journal following OPR where the reviewer‘s reports and the author‘s responses would be included in the final publication;

Q3—Would you accept to review an article for a journal following OPR knowing that your identity and report would be included in the final publication;

Q4—Would you submit a scientific article at a journal following PLoS review process, meaning fast publication based on the technical soundness of research without any judgement on its novelty;

Q5—Would you submit a scientific article at a journal following F1000 Research review process, meaning fast post-publication peer review after a basic formal check done by selected experts and readers.

Answer options: Option 1: Disagree, Option 2: Somewhat disagree, Option 3: Somewhat agree, Option 4: Agree.

References

- Directorate-General for Research and Innovation (European Commission). Open Innovation, Open Science, Open to the World a Vision for Europe; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016; ISBN 978-92-79-57346-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster Open Science. Available online: https://www.fosteropenscience.eu/taxonomy/term/7 (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Max Planck Society. Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the Sciences and Humanities. Available online: https://openaccess.mpg.de/Berlin-Declaration (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Budapest Open Access Initiative. Available online: https://www.budapestopenaccessinitiative.org/read (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Bethesda Statement on Open Access Publishing. Available online: http://legacy.earlham.edu/~peters/fos/bethesda.htm (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- European Commission. The EU’s Open Science Policy. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/research-and-innovation/strategy/goals-research-and-innovation-policy/open-science_en (accessed on 16 February 2021).

- Foster Open Science Definition. Available online: https://www.fosteropenscience.eu/foster-taxonomy/open-science-definition (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Aliende, P.; Luisa, M. Open Science and Open Research Data: Requirements in Horizon 2020. Presented at the Workshop Celebrado en la Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, en el Marco del Programa CONEX (CONnecting EXcellence to UC3M), Spain, November 2017; Available online: https://repositorio.uam.es/handle/10486/680255 (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Ayris, P.; LÃpez de San Román, A.; Maes, K.; Labastida, I. Open Science and Its Role in Universities: A Roadmap for Cultural Change. League of European Research Universities. LERU, 2018; p. 32. Available online: https://www.leru.org/publications/open-science-and-its-role-in-universities-a-roadmap-for-cultural-change (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- European Commission: OSPP-REC Open Science Policy Platform Recommendations; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Sanchez, A.F.; Iriarte, P. Some Fundamentals for Open Research Data Management in Health Sciences. JEAHIL 2017, 13, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, S.; Genova, F.; Harrower, N.; Hodson, S.; Jones, S.; Laaksonen, L.; Mietchen, D.; Petrauskaite, R.; Magnus, V.; Wittenburg, P. Turning FAIR into Reality-Final Report and Action Plan from the European Commission Expert Group on FAIR Data; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, T. Turning FAIR into Reality. Review Learn. Publ. 2019, 32, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, N.C.; Cozzino, S.; Genova, F.; Hoffman-Sommer, M.; Hooft, R.; Lembinen, L.; Martilla, J.; Marta Teperek, M.; Berezko, O. Six Recommendations for Implementation of FAIR Practice; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross-Hellauer, T. What Is Open Peer Review? A Systematic Review. F1000Research 2017, 6, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janowicz, K.; Hitzler, P. Open and Transparent: The Review Process of the Semantic Web Journal. Learn. Publ. 2012, 25, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willinsky, J.; Moorhead, L. How the Rise of Open Access Is Altering Journal Publishing. In The Future of the Academic Journal, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 195–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennant, J.P.; Dugan, J.M.; Graziotin, D.; Jacques, D.C.; Waldner, F.; Mietchen, D.; Elkhatib, Y.; Collister, L.B.; Pikas, C.K.; Crick, T.; et al. A multi-disciplinary perspective on emergent and future innovations in peer review. F1000Research 2017, 6, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burley, R.; Moylan, E. Foreword In What Might Peer Review Look like in 2030? A report from BioMed Central and Digital Science. pp. 2–3, Figshare. Available online: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.4884878.v1 (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Poschl, U. Interactive Open Access Publishing and Public Peer Review: The Effectiveness of Transparency and Self-Regulation in Scientific Quality Assurance. IFLA J. 2010, 36, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Boldt, A. Extending ArXiv.Org to Achieve Open Peer Review and Publishing. J. Sch. Publ. 2011, 42, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley Transparent Peer Review. Available online: https://authorservices.wiley.com/asset/Transparent%20Peer%20Review.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Wolfram, D.; Wang, P.; Hembree, A.; Park, H. Open Peer Review: Promoting Transparency in Open Science. Scientometrics 2020, 125, 1033–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federer, L.M.; Lu, Y.L.; Joubert, D.J.; Welsh, J.; Brandys, B. Biomedical Data Sharing and Reuse: Attitudes and Practices of Clinical and Scientific Research Staff. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0129506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuiderwijk, A.; Shinde, R.; Jeng, W. What Drives and Inhibits Researchers to Share and Use Open Research Data? A Systematic Literature Review to Analyze Factors Influencing Open Research Data Adoption. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fecher, B.; Friesike, S.; Hebing, M. What Drives Academic Data Sharing? PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holub, P.; Kohlmayer, F.; Prasser, F.; Mayrhofer, M.T.; Schlünder, I.; Martin, G.M.; Casati, S.; Koumakis, L.; Wutte, A.; Kozera, Z.; et al. Enhancing Reuse of Data and Biological Material in Medical Research: From FAIR to FAIR-Health. Biopreserv. Biobank. 2018, 16, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/publications/topic/hipaa.html (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Benitez, K.; Malin, B. Evaluating Re-Identification Risks with Respect to the HIPAA Privacy Rule. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2010, 17, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenopir, C.; Allard, S.; Douglass, K.; Aydinoglu, A.U.; Wu, L.; Read, E.; Manoff, M.; Frame, M. Data Sharing by Scientists: Practices and Perceptions. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, J.; Johnson, F.; Sbaffi, L.; Frass, W.; Devine, E. Academics‘ Behaviors and Attitudes towards Open Access Publishing in Scholarly Journals. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2017, 68, 1201–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savage, C.J.; Vickers, A.J. Empirical Study of Data Sharing by Authors Publishing in PLoS Journals. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e7078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enke, N.; Thessen, A.; Bach, K.; Bendix, J.; Seeger, B.; Gemeinholzer, B. The User‘s View on Biodiversity Data Sharing-Investigating Facts of Acceptance and Requirements to Realize a Sustainable Use of Research Data. Ecol. Inform. 2012, 11, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.J.; Merry, A.F. Data Sharing for Pharmacokinetic Studies. Paediatr. Anaesth. 2009, 19, 1005–1010. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.1460-9592.2009.03051.x (accessed on 10 December 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antman, E. Data Sharing in Research: Benefits and Risks for Clinicians. BMJ 2014, 348, g237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, S.; Kim, S.; Kim, Y. An Exploratory Study Of Health Scientists’ Data Reuse Behaviors. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 69, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y. Research Data Sharing And Reuse Practices Of Academic Faculty Researchers: A Study Of The Virginia Tech Data Landscape. Int. J. Digit. Curation 2016, 10, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unal, Y.; Chowdhury, G.; KurbanoÄlu, K.; Boustany, J.; Walton, G. Research Data Management and Data Sharing Behaviour of University Researchers. Inf. Res. Int. Electron. J. 2019, 24. Available online: http://InformationR.net/ir/24-1/isic2018/isic1818.html (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Kim, Y.; Zhang, P. Understanding Data Sharing Behaviors of STEM Researchers: The Roles of Attitudes, Norms, and Data Repositories. Libr. Inf. Sci. Res. 2015, 37, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronick, D.A. Peer Review in 18th-Century Scientific Journalism. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1990, 263, 1321–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, K. Peer-to-Peer Review and the Future of Scholarly Authority. Soc. Epistemol. 2010, 24, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fry, J.; Probets, S.; Creaser, C.; Greenwood, H.; Spezi, V.; White, S. PEER D4.2 Behavioural Research: Authors and Users Vis-Ã -Vis Journals and Repositories-Final Report PEER Behavioural Research: Authors and Users Vis-Ã -Vis Journals and Repositories Final Report Contents. 2011. Available online: https://hal.inria.fr/hal-00736168 (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Poltronieri, E.; Bravo, E.; Camerini, T.; Ferri, M.; Rizzo, R.; Solimini, R.; Cognetti, G. Where on Earth to Publish? A Sample Survey Comparing Traditional and Open Access Publishing in the Oncological Field. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 32, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.J.; Sugimoto, C.R.; Zhang, G.; Cronin, B. Bias in Peer Review. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2013, 64, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, P. Peer Review: Decisions, Decisions. Elife 2017, 6, e32011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennant, J. The Dark Side of Peer Review. Editor. Off. News 2017, 10, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmer, M.; Schottdorf, M.; Neef, A.; Battaglia, D. Gender Bias in Scholarly Peer Review. Elife 2017, 6, e21718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangas, A.; Hujala, T. Challenges in Publishing: Producing, Assuring and Communicating Quality. Silva Fenn. 2015, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Sueur, H.; Dagliati, A.; Buchan, I.; Whetton, A.D.; Martin, G.P.; Dornan, T.; Geifman, N. Pride and Prejudice–What Can We Learn from Peer Review? Med. Teach. 2020, 42, 1012–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Q.; Xie, Y.; Liang, J. Does Open Peer Review Improve Citation Count? Evidence from a Propensity Score Matching Analysis of PeerJ. Scientometrics 2020, 125, 607–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowar, H.A.; Day, R.S.; Fridsma, D.B. Sharing detailed research data is associated with increased citation rate. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angadi, H.S. Is Open Peer Review the Future of Refereeing? A Narrative Review. 2020. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3603564 (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Schmidt, B.; Ross-Hellauer, T.; van Edig, X.; Moylan, E.C. Ten Considerations for Open Peer Review. F1000Research 2018, 7, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennant, J.P.; Ross-Hellauer, T. The limitations to our understanding of peer review. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2020, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frass, W.; Cross, J.; Gardner, V. Taylor & Francis Open Access Survey June 2014. 2014. Available online: https://www.tandf.co.uk//journals/explore/open-access-survey-june2014.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Vlachaki, A.N. Open Access Publishing and Scholarly Communication among Greek Biomedical Scientists. Ph.D. Thesis, Aberystwyth University, Aberystwyth, Wales. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2160/44a8db70-0e07-46f5-b810-53c60cd96942 (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Rath, M.; Wang, P. Open Peer Review in the Era of Open Science: A Pilot Study of Researcher‘s Perceptions. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM/IEEE Joint Conference on Digital Libraries (JCDL), Toronto, Canada, 19–23 June 2017; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, J.; Pierce, M.; Boughton, S.L.; Baldeweg, S.E. Do Peer Review Models Affect Clinicians‘ Trust in Journals? A Survey of Junior Doctors. Res. Integr. Peer Rev. 2017, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulligan, A.; Hall, L.; Raphael, E. Peer Review in a Changing World: An International Study Measuring the Attitudes of Researchers. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2013, 64, 132–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, D.; Watkinson, A.; Jamali, H.R.; Herman, E.; Tenopir, C.; Volentine, R.; Allard, S.; Levine, K. Peer Review: Still King in the Digital Age. Learn. Publishing. Assoc. Learn. Prof. Soc. Publ. 2015, 28, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenopir, C.; Levine, K.; Allard, S.; Christian, L.; Volentine, R.; Boehm, R.; Nichols, F.; Nicholas, D.; Jamali, H.R.; Herman, E.; et al. Trustworthiness and Authority of Scholarly Information in a Digital Age: Results of an International Questionnaire. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2016, 67, 2344–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).