Abstract

This article describes the development of the digital infrastructure at a research data centre for audio-visual linguistic research data, the Hamburg Centre for Language Corpora (HZSK) at the University of Hamburg in Germany, over the past ten years. The typical resource hosted in the HZSK Repository, the core component of the infrastructure, is a collection of recordings with time-aligned transcripts and additional contextual data, a spoken language corpus. Since the centre has a thematic focus on multilingualism and linguistic diversity and provides its service to researchers within linguistics and other disciplines, the development of the infrastructure was driven by diverse usage scenarios and user needs on the one hand, and by the common technical requirements for certified service centres of the CLARIN infrastructure on the other. Beyond the technical details, the article also aims to be a contribution to the discussion on responsibilities and services within emerging digital research data infrastructures and the fundamental issues in sustainability of research software engineering, concluding that in order to truly cater to user needs across the research data lifecycle, we still need to bridge the gap between discipline-specific research methods in the process of digitalisation and generic digital research data management approaches.

1. Introduction

Over the last few decades, the development of digital practices in the humanities and social sciences has accelerated and become more widespread, partly along with digitalisation of society in general and partly as a result of targeted funding. One of the main aims of such funding was, in Germany, to develop the digital research (data) infrastructure required to make digital language resources, tools and methods generally available to scholars. Funded projects included the infrastructures CLARIN-D1 and DARIAH-DE2—the national consortia of the European research infrastructures CLARIN3 and DARIAH4, respectively—established in 2011 following successful test phases, and several interdisciplinary eHumanities Centres receiving funding as of 2013. At the involved data centres, digital repositories have been set up for archiving and dissemination of language resources, mainly resulting from research projects. The following article discusses how the complex digital infrastructure of such a research data centre, the Hamburg Centre for Language Corpora within the CLARIN-D infrastructure, has emerged in compliance with standards and best practices of research data management while catering to various usage scenarios and user needs. At the Hamburg Centre for Language Corpora at the University of Hamburg, digital infrastructure and related services have been developed focussing on spoken data in research on multilingualism, linguistic diversity and language documentation, i.e., often the kind of audio-visual annotated linguistic research data referred to as spoken or oral (language) corpora. These complex collection resources comprise various data types, entities and relations which pose a challenge for data modelling and handling. Contributing to the current discussion on reuse and citation of research data and the replicability of research in general, this contribution also describes evolving methods for curation, publication and dissemination of complex resource types considering these aspects.

2. Background and Basic Concepts

In 2011, as the maximum funding period of twelve years had been reached for the Special Research Centre on Multilingualism at the University of Hamburg, The Hamburg Centre for Language Corpora (HZSK)5 was founded with the aim to cater for the legacy of curated research data and software from the Special Research Centre and for the newly founded centre to become a part of emerging digital research infrastructures. Within the subproject responsible for research data management of the Special Research Centre, the software suite EXMARaLDA [1] had been developed and used to create or curate spoken language corpora from more than 25 data sets [2]. Since the software had also gained popularity beyond the Special Research Centre, the data management subproject was providing advice and training to national and international colleagues.

The software suite and the large collection of spoken multilingual corpora were the basis for the work taken up by the centre, financed by two third-party funded projects, aimed at further developing the technical infrastructure of the centre and integrating its resources into the CLARIN infrastructure as a certified CLARIN service centre. For the certification, centres need to provide digital infrastructure and interfaces which comply with the CLARIN requirements [3]. Apart from the HZSK, other centres within the CLARIN context were also developing repositories or similar solutions to store and disseminate audio-visual data, such as the Bavarian Archive for Speech Signals [4], which focuses on phonetics research, The Language Archive at the MPI in Nijmegen, which holds the DOBES Documentation of Endangered Languages collections [5,6], and the Institute for German Language, which provides the Database of Spoken German [7]. Through CLARIN, common technical ground was now required to achieve basic interoperability across the infrastructure. The technical aspects of the HZSK infrastructure, in particular the HZSK Repository, will be further described in Section 3.

Due to the experience gained over the previous years, the HZSK became responsible for the Support and Help Desk work package in the CLARIN-D project, operating the national CLARIN-D Help Desk [8]. The HZSK provided first line support and administration of incoming inquiries among the other eight CLARIN-D centres. Supporting researchers with advice and training in all questions related to data management across the research data lifecycle has proven to be a crucial complement to providing the necessary technical infrastructure, and over the years an increasing number of support areas were integrated into the help desk at the HZSK [9]. Since 2018, the HZSK also provides its expertise internationally in cooperation with several well-known partners via the CLARIN Knowledge Centre on Linguistic Diversity and Language Documentation (CKLD) [10].

The initial two projects providing the actual funding for work within the HZSK both completed their first and second project phases successfully and the CLARIN-D project is reaching the end of its final third phase. Since 2016, in total five different projects have been involved in the further development of the HZSK infrastructure, all applied for in close cooperation with the HZSK management. Apart from the CLARIN-D and CLARIAH-DE6 projects focussing directly on work as a service centre in the now merged infrastructures CLARIN-D and DARIAH-DE, the ZuMult7 project aims to improve access to spoken language corpora for various user groups through new interfaces. Furthermore, the data curation workflows and the quality control framework developed at the HZSK [11] are being maintained and adapted for the specific needs of the long-term project INEL8, which is based on the HZSK infrastructure and creates annotated spoken corpora of Northern Eurasian indigenous languages. The most recent project, QUEST: Quality—Established9 is based on the existing cooperation within the CLARIN knowledge centre CKLD and aims at enhancing data quality and reuse by harmonising general and reuse scenario specific requirements across the participating centres. Again, the quality control framework developed at the HZSK plays a major role, as it will be extended to cover further resource and data types and also be made available to external projects for semi-automatic quality control during data creation and to assess the data before deposit. Over the years, the corpus collection of the HZSK has reached double the initial number, today comprising more than 60 corpora, most within the focus area of multilingual and spoken data.

2.1. Resource Types: Spoken Language Corpora and Other Audio-Visual Collections

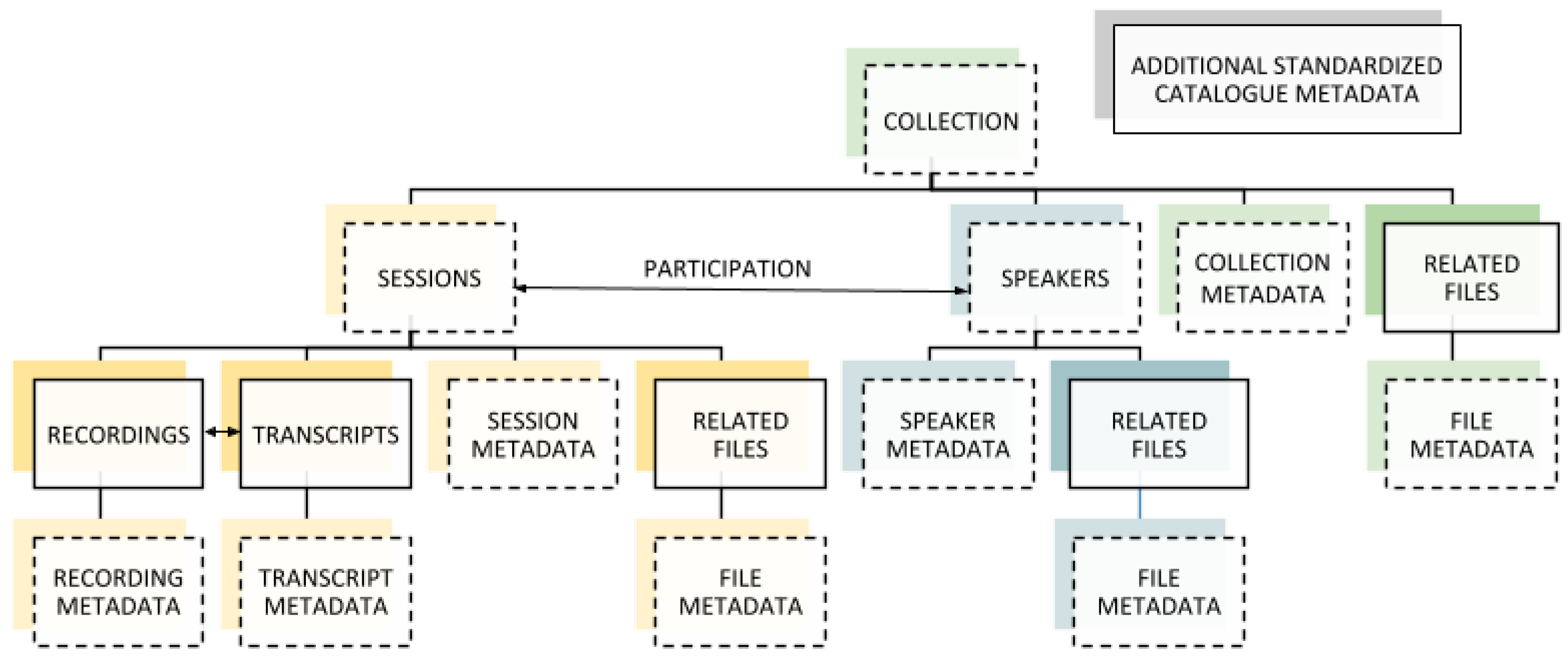

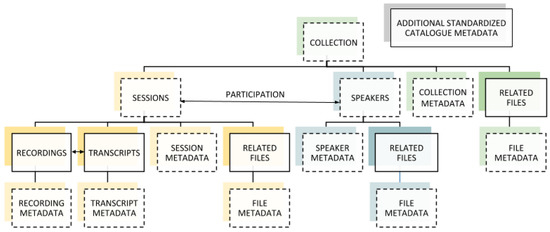

The data hosted at the HZSK was created within a diverse range of research fields, mainly included in or closely related to (applied) linguistics, e.g., language acquisition, multilingualism, language contact, language documentation or typological research. From the data modelling perspective, depicted in Figure 1, resources are fairly homogeneous, they comprise recordings with written records of the spoken words—transcripts—possibly also including further information relevant for analysis—annotations—and contextual information on the setting and the participants of the recorded event often referred to as session and speaker metadata. The resource as a whole is again described with resource type specific metadata and, as a part of the publication process, generic standardised metadata to ensure discoverability. By allowing for highly resource specific metadata through the flexible EXMARaLDA metadata schema and using this original metadata as the basis for a smaller set of highly standardised metadata, conflicting requirements on metadata for the discovery and analysis of resources can be met. This type of complex resource containing various data types and abstract entities with different kinds of relationships obviously differs considerably from single documents or even sets of similar resources without internal structure and the implications for handling and versioning are equally far-reaching.

Figure 1.

An audio-visual collection: the spoken language corpus.

The research questions leading to the creation of rather similar resources are highly diverse, as are the research methods applied. All sub types do, however, have in common that data have to be created manually, as automatic transcription, despite recent advances, can only be applied for well-documented languages and varieties, not for an endangered language that is being documented for the first time or for the non-standard multilingual (learner or code-switching) varieties under investigation. This also applies for the further enrichment with often project specific analytical information, usually referred to as annotation or coding. While tagging words with their parts of speech might be feasible to do in a semi-automatic manner after gathering an adequate amount of training data, the annotation process for more complex types of information is usually highly interpretative, requiring a human annotator to consider several linguistic and extra-linguistic parameters. Manually created data have the disadvantage that consistency might suffer due to the flexibility needed for the data creation process. An even greater challenge is keeping data consistent in projects using a qualitative approach where data analysis is not a single step but something that is carried out in an iterative-cyclic manner, where annotation schemes are continuously being adapted to the data and insights gained from their investigation.

Since analytical categories of annotation schemes correspond to specific research questions, even if the resource types are similar, the types of information added within the structures of a proposed common model differ widely and can never be standardised across research paradigms or research questions. This also holds true for the ways in which transcript and annotation data are visualised and analysed. Qualitative approaches such as discourse or conversation analysis are based on transcripts with particular layout features and transcription conventions, and these characteristics correspond to theoretical frameworks and fundamental assumptions about language and communication (cf. [12,13]).

2.2. Usage Scenarios and Dissemination

Among the HZSK corpora are data sets from research on various aspects relevant to multilingual societies (e.g., community interpreting in hospitals, multilingual language acquisition in children and adult learners, or documentation of multi-ethnic youth sociolects), data sets documenting particular dialects or endangered indigenous languages, and data sets capturing linguistic variation and change in language contact settings.

The users of the HZSK infrastructure and services vary along the research data lifecycle: researchers creating digital language resources within the thematic focus of the centre receive advice and support during this process and while preparing the deposit of their data. The depositors are still a heterogeneous group, ranging from PhD students providing the data set on which their thesis was based to large research projects with several institutional partners. However, they share the requirements of a trustworthy, i.e., certified, archive with secure access to the data for future reuse, which also ensures high discoverability of the hosted resources.

Further along the research data lifecycle, we find the users who reuse the data provided by the depositors via the HZSK Repository, including both students writing term papers and experienced researchers performing secondary or complementary analyses with existing data. Due to the thematic focus of multilingual data and data from lesser-resourced and endangered languages, users’ geographical and linguistic backgrounds also vary greatly. While most reuse scenarios remain within the original research field, targeting related research questions, users analyse data within various research paradigms and theoretical frameworks, and they utilize qualitative or quantitative methods. Only data that are consistent and machine-readable can be used within quantitative approaches. A user study of users of three spoken corpus platforms [14] outlines that although advanced querying of the data across various information types is made available, close reading of transcripts with aligned media is the method most commonly used. For reasons described in the previous section, users are in this case in general only comfortable with a certain transcript layout. Beyond further analyses, some users build new resources based on existing ones, such as corpus-based grammatical descriptions of endangered languages or typological data sets. Several data sets of the Special Research Centre on Multilingualism were used as the basis for derived resources and reused within third mission reuse scenarios, e.g., to provide relevant training in interpreting situations for hospital staff [15].

3. The Infrastructure at the HZSK

The HZSK Repository10 [16] is the core component of the HZSK infrastructure, which comprises a number of tools and services required to meet relevant user or stakeholder requirements. It has been developed considering general requirements for research data repositories (e.g., as formalized by the FAIR Principles [17]), which partly need to be implemented as resource type specific requirements and requirements related to the diversity of usage scenarios. The HZSK Repository was certified with the Data Seal of Approval11 2011 and 2014-2017 and the CoreTrustSeal certification12 2017–2019. Based on the software Fedora Commons13 and Islandora14, which is in turn based on the widely used open-source CMS Drupal15, it features an Islandora-based web interface with a Solr16 search facility, with all components adapted to the underlying data model for (EXMARaLDA) spoken language corpora.

3.1. Findable Data through Diverse Metadata and Fine-Grained PIDs

For data to be findable, they have to be visible where designated users actually search and the metadata needs to be appropriate for them to decide on possible usage scenarios. By providing standardised metadata in both specific (CMDI17 of the CLARIN infrastructure) and generic (Dublin Core18) formats via OAI-PMH19, resources become discoverable, e.g., via the CLARIN Virtual Language Observatory20. This additional metadata is generated from parts of the original contextual metadata on recording sessions and participants and further resource documentation expressed by the EXMARaLDA metadata format by specific mappings and conversion services. Finally, since the corpora are also of interest to researchers focusing on the content—such as oral traditions or historical events—not the language itself, within a pilot project in cooperation with the Information Service for Northern European Studies21, library catalogue records for suitable corpora have been created, making them discoverable as electronic resources from local catalogues to the WorldCat22.

When it comes to Persistent Identifiers (PIDs) for complex resources, apart from making data reliably findable, another important aspect is the possibility of rearranging sessions from different resources into new virtual collections, e.g., to gather data from English language learners from various contexts, which requires a finer granularity with PIDs on the level of the recording session and for individual files and part identifiers for various derived file formats.

3.2. Accessible Data through a Comprehensive AAI Solution

The CLARIN infrastructure differentiates between three distribution types for digital resources and services: public access, academic access (via single sign-on), and restricted access. Due to data protection, public access is rarely possible for spoken data collected in the European Union, and only certain resources can be made available for all users logging in with an institutional account from an academic organisation. Most spoken corpora can only be provided with restricted access, sometimes with explicit consent of the depositor on a case-to-case basis required. Making spoken corpora accessible thus requires a comprehensive Authentication and Authorisation Infrastructure (AAI) solution with individual requests and access management. Within the HZSK Repository, the Drupal Shibboleth Module is used to enable the strictly Shibboleth-based authentication. Authorisation is partly based on entitlement information on academic status transferred on login, which automatically maps to Drupal roles for resources available for academics. For requests for access to restricted resources, a semi-automatic workflow including the CLARIN-D Help Desk has been developed [18]. Due to data protection, particularly German institutions using Shibboleth are still very restrictive when it comes to attribute release, i.e., in some cases the information required to uniquely identify users is withheld from the service provider. Though the situation has improved over the years, this is still a source of frustration for users, since the responsibilities for the technical problems are unclear to them and they end up using alternative accounts provided by the CLARIN ERIC.

3.3. Interoperable Data through Standards and Open Formats

Apart from using open standard media formats, the EXMARaLDA formats and all metadata formats are XML-based open formats. Furthermore, the EXMARaLDA software provides advanced interoperability with most widely used similar tool formats such as ELAN [19], Transcriber [20], Praat [21], Chat/CLAN [22], and the ISO 24624:2016 Transcription of spoken language [23] based on the widely used Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) specification [24]. This makes the hosted resources highly interoperable. Apart from merely browsing and viewing data, however, many users require digital data to be searchable using advanced queries or further annotated and analysed. For these usage scenarios, there are highly specialised platforms and tools available, e.g., ANNIS [25], WebAnno [26], WebLicht [27] and Tsakorpus23, which have been developed for many years and are widely used within the respective research communities. The approach is therefore to ensure and enhance interoperability for the data hosted at the HZSK and integrate these existing components into the digital infrastructure instead of developing similar functionality. By implementing conversion services and import filters (cf. [28,29,30]), it becomes possible to extend the repository solution to changing requirements and usage scenarios.

3.4. Reusable Data for Various Usage Scenarios

Since the FAIR Principles refer to “relevant attributes” and “domain-relevant community standards” (cf. R1., R1.3. of the FAIR Principles), in order to provide data that are reusable in as many ways as possible, the needs of existing and potential designated communities regarding necessary information and standard formats for the relevant resource type have to be considered. A truly crucial component of the HZSK infrastructure is the help desk, which not only provides efficient user support, but also offers a unique opportunity to gain insights into user behaviour and needs that have not yet been adequately met, which is imperative for non-tech users interacting with digital tools and complex resources. For instance, the information on licensing and terms of use is far more complex than for other resource types due to data protection and the risks of de-anonymization inherent in any resource containing necessarily rich information on members of small linguistic communities. Through the manual creation process, information on provenance is usually equally complex, and for legacy data, detailed information has most often not been preserved. For current resources, however, a thorough description of the creation process and of all conventions and schemata used is strongly recommended for depositors with the HZSK Repository to allow users to make informed decisions on possible reuse scenarios for specific resources. As described in Section 2.2, different visualisations of the source transcription and annotation data need to be provided for users from different disciplines and theoretical frameworks. Linguistic corpora might be heavily annotated with grammatical information and thus hard to decipher for non-linguists unless irrelevant information can be excluded in the visualisation. Since the EXMARaLDA desktop software already provided output options for various transcript layouts using XSLT to create HTML from the XML data, similar functionality was developed for the repository resulting in a set of extendable visualisation services.

4. Developing Strategies for Data Curation and Publication

Over the years, in response to technical requirements and developments on the one hand, and user needs on the other, strategies employed to facilitate data curation and publication have also changed. The first major cause for these changes was the possibilities of the specialised repository, the second rather related to some of its limitations, but mainly to the need to reduce the amount of data curation efforts and costs.

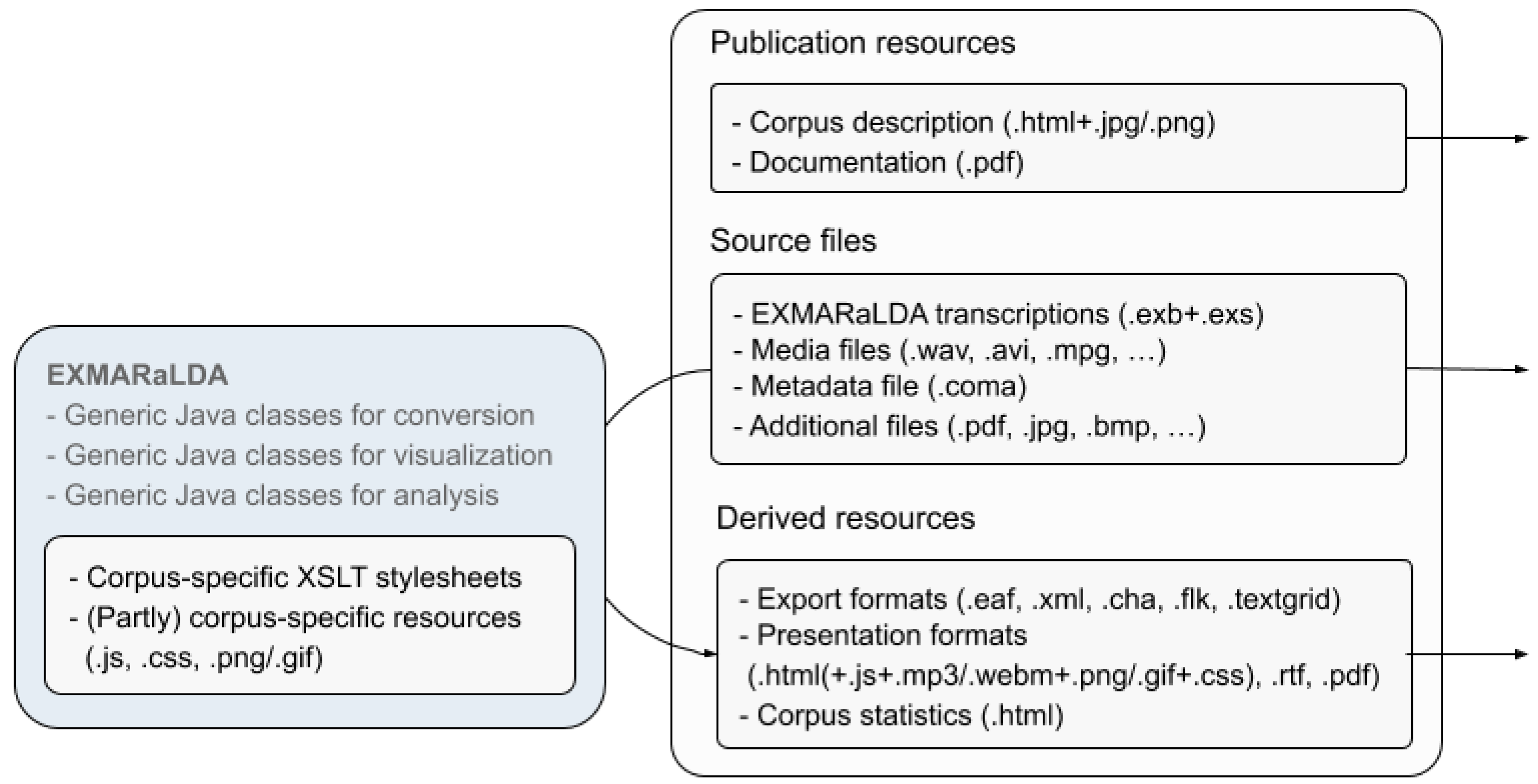

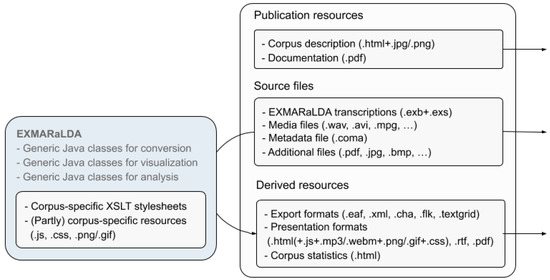

4.1. Static and Dynamic Digital Language Resources

Prior to the dissemination via the HZSK Repository, a simple web server solution was used, obviously lacking several benefits of the current approach using dedicated repository software, e.g., regarding versioning of digital objects or user management. The data creation and curation processes at the Special Research Centre on Multilingualism were controlled by the data management sub project, either directly, when building corpora from legacy data in various formats, or indirectly, by providing comprehensive support to individual research projects using the EXMARaLDA software to create data. In preparation for publication, corpus-specific methods based on the EXMARaLDA system were used to generate a comprehensive hypertextual resource from the EXMARaLDA source files for transcription/annotation data and contextual metadata. Apart from HTML visualisations, the resulting resource also comprised additional tool and visualisation formats (e.g., in often requested PDF format) and statistical overviews, as displayed in Figure 2. The protected resources were accessed via a public web page containing further background information and documentation.

Figure 2.

Static website resource model.

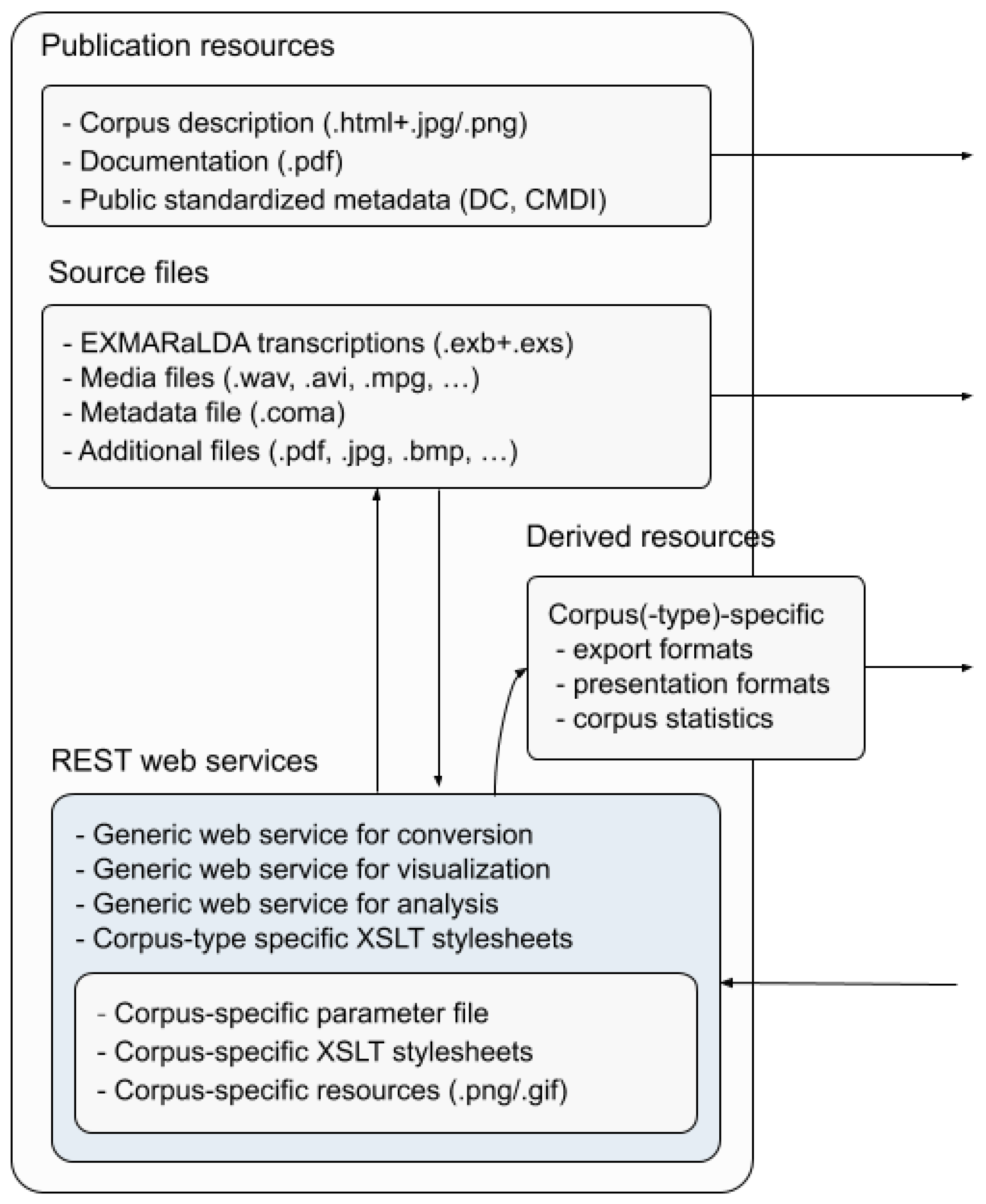

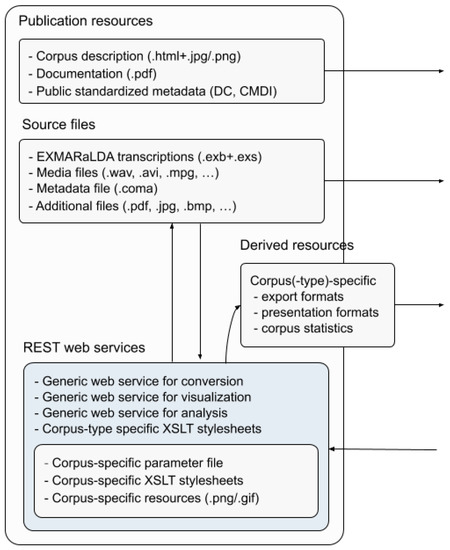

Since a digital repository enforces concepts such as persistent identifiers, versioning of digital objects and ingest/dissemination services, it was decided to include only the EXMARaLDA source files in the data model for the Fedora repository and (re-)implement visualisation and conversion functionality previously employed before publication as web services integrated into the repository. This solution, depicted in Figure 3, brought about important differences: The digital resource is no longer a collection of static web pages and files; the user interacts with web services that change as target formats or the services themselves are further developed. Most importantly, if users mainly analyse visualised transcripts, whose characteristics are known to influence analysis, the requirement of citable corpus versions would imply the explicit tracking and providing of the versions of web services and further components used for visualisation, such as corpus (type) specific stylesheets (e.g., for research on (child) language acquisition or regional varieties). Considering that reuse and reliable citing are only now emerging as commonly used practices within the digital humanities, users are generally not aware of such conceptual problems, and standard procedures for this area are still a desideratum. Of course, the flexibility gained by generating requested formats interactively on-the-fly would also enable an enhanced user experience, since it would allow both for different presentation styles consistent with the original research questions and frameworks for different resources, or, conversely, allow for a more consistent user experience by applying certain settings to various corpus types in the repository. However, this requires additional effort in data preparation, as some formats require certain information to be available, sometimes in a particularly detailed or consistent manner, thus the possibilities depend not only on the web services but also on the characteristics related to corpus design, annotation layers and transcription conventions specific to corpus types or individual data sets.

Figure 3.

Dynamic repository resource model.

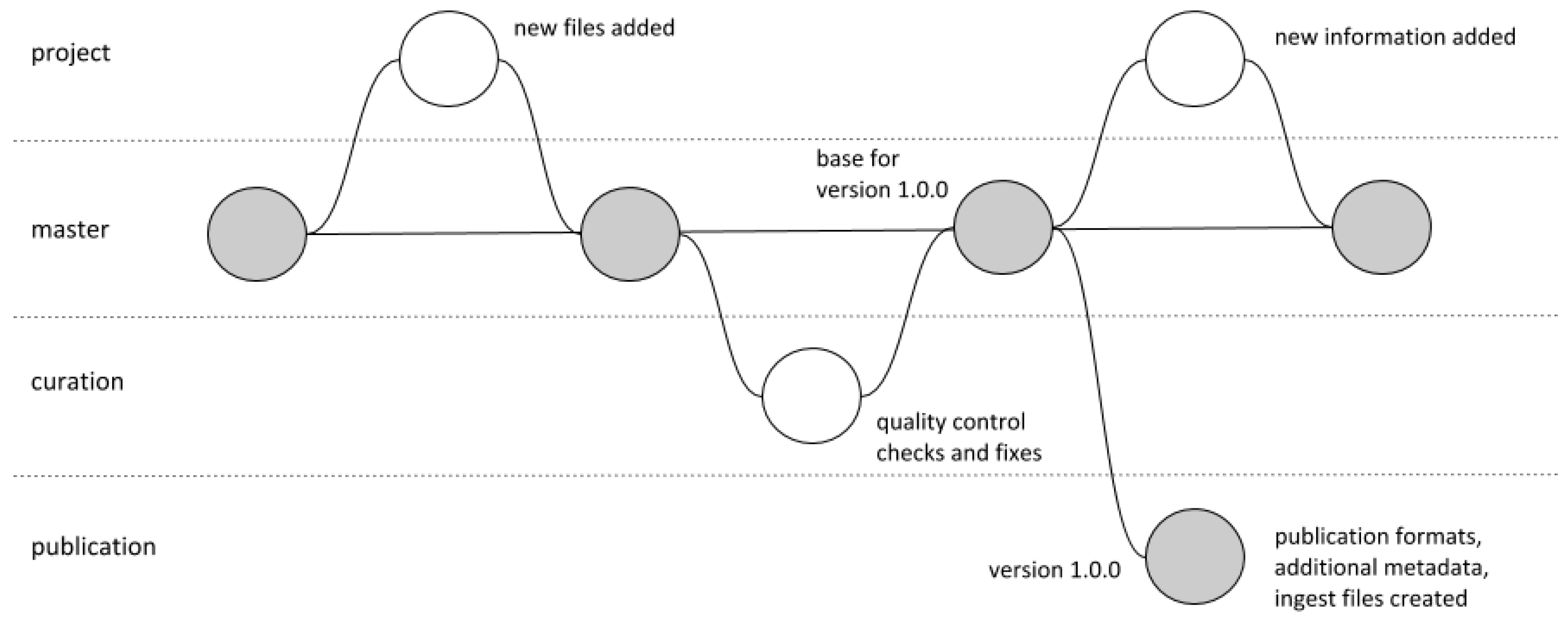

4.2. Efficient and Transparent Data Curation Workflows

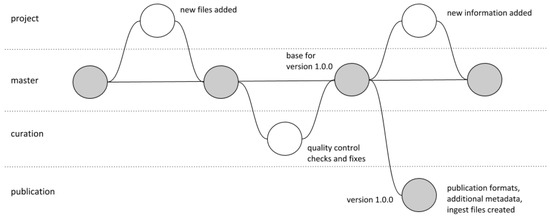

Whereas the first set of corpora in the HZSK collection had been created by technical staff to a large extent, later deposited resources were created by external research projects using the EXMARaLDA software suite or similar tools. This posed a great challenge in terms of assuring data quality and integrity as data needed to be extensively curated for distribution via the HZSK repository and the number of deposits were increasing due to funders’ recent requirements on research data management and reuse. To meet this challenge, another infrastructure component was developed, the HZSK Corpus Services [11], a comprehensive set of automatic data validation and diagnostics services within an extensible software framework partly based on the EXMARaLDA source code. Before deposit, ideally continuously during the data creation process, data can be thoroughly assessed and any problems pointed out in detail. The internal curation and publication preparation processes have been formalised by customised workflows in the project management software Redmine24 integrating version control by Git25. The Git branching concept depicted in Figure 4 ensures transparency regarding any changes made before publication, including the generation of all derived resources to be published. With the HZSK Corpus Services, the previously employed method of creating a complete static resource has been revisited and updated to current technical solutions including quality control and the knowledge gathered on users’ needs.

Figure 4.

Version-controlled workflow for curation and publication of language resources.

5. Distributing Highly Specific Data via Generic Repositories—FAIR Enough?

As of July 2019, the University of Hamburg provides a permanent generic research data repository at the newly established Center for Sustainable Research Data Management26, FDR27, currently based on the Zenodo28 codebase but scheduled to be replaced by InvenioRDM29. To ensure sustainability, the digital resources held at the HZSK will be migrated to this repository as the third-party funded infrastructure projects are ending. However, the repository does not provide any specialised functionality for language corpora, and the upcoming challenge will be to ensure that FAIRness and the usability of the highly specific data remains as far as possible within the generic repository. In deciding which functionality is truly relevant, it is again important to both consider current user needs on the one hand, and standards and best practices promoted by other stakeholders and experts on the other.

In the FDR, resources remain findable through corpus level DOIs, but the fine grained citability and the corresponding possibility of building new virtual collections will be lost, with resources only provided as a set of files. The DataCite metadata schema30 does not provide specific elements for language resources as the CLARIN CMDI metadata profiles of the HZSK do, and the resources will not be discoverable via the advanced faceted search of the CLARIN VLO. However, as many users are still unaware of specialised services such as the VLO or virtual collections, there is still time to improve support for all kinds of collection/compound resources and the format options for metadata to be provided via OAI-PMH.

Although the resources will remain accessible, functionality is reduced. The current AAI solution is based on the institutional IDM of the University of Hamburg, complemented by local accounts as data owners leave or external researchers request access to resources. The institutional single sign-on for academic use via Shibboleth is not available, and the data owners manage all authentication and authorisation processes related to granting access to their resources themselves. From the user’s perspective, registering and receiving a password is probably acceptable, but authentication is a problem without true identity management and local accounts remains a risk, even if attacks are rare31. As most users are still handling different accounts related to their academic identity, e.g., to log on to the university intranet or to download an article from a journal provided by the university library, and the issues with attribute release are still in the process of improving, likewise, single sign-on for access to academic resources can still be developed.

Since the data will still be provided in the highly interoperable EXMARaLDA XML formats, partly complemented by pre-generated formats for other relevant and widely used tools and platforms, this aspect is at a first glance unproblematic. However, for most users of language resources, interoperability requires existing methods for conversion, which are still to be implemented for future formats. This is not part of the service portfolio of the Centre for Sustainable Research Data Management, which only provides bit-stream preservation, and also not an issue that can be solved by a single centre for all the formats hosted in a generic research data repository.

Through the return to complete static resources, the data can be made reusable even though the repository software does not include any specialised solutions for this type of data. From the user perspective, viewing a pre-generated HTML visualisation with integrated media file playback might even be superior to the solution with interactive visualisation of resources, since these might from time to time become a source of confusion or frustration if they are not working properly or their behaviour changes frequently, which is not unusual for software components still being developed.

6. Discussion

When user needs are taken into account, it becomes clear that even for rather specific resource types, users and their needs differ widely and change over time. For a digital infrastructure based on a repository to meet varying user needs beyond basic services such as long-term preservation, persistent identification and reliable access for data sets, a high degree of flexibility is required. This requirement becomes more difficult to meet for an institutional repository hosting a vast number of different resource types with users from equally different disciplines. Though the migration of the data from the resource type specific HZSK repository to the new institutional repository will at first render the data less FAIR, over time, the findability and accessibility, aspects for which the requirements are similar across many usage scenarios, will most likely improve as the repository software is further developed within a sustainable international cooperation. On the other hand, interoperability and reusability are aspects that are directly related to individual resource types and emerging or developing community standards. Even within a strong international cooperation, the general question regarding the feasibility of maintaining a high number of specialised solutions within a common repository software remains.

The infrastructure at the HZSK was developed to meet the needs of different user groups not by providing all conceivable functionality in one component, but by integrating various widely used specialised components to be replaced or complemented as needed in a modular approach. Ideally, these components are open source solutions to which several teams and projects can contribute, both by extending the functionality and by sharing the necessary maintenance work, thus ensuring the sustainability of the individual components. This is one way in which even highly specialised tools and services developed in the context of third-party-funded research projects might become more established and sustainable over time, but without permanent funding, they might also at any time become abandonware, which might in some cases even be justified when technological solutions have become obsolete. For research data to persist regardless of technical solutions used for archiving and distribution, semantic interoperability is crucial, since manual curation for migration and preservation purposes will not always be feasible. If the data are consistent and machine-understandable, various tool and presentation formats can be generated and disseminated at any time with comparatively little effort, since automatic processing and conversion of all data becomes possible. However, standards which will ensure that data are machine-understandable still need to be developed and widely recognised.

Though quality criteria focusing on data consistency and structural correctness might seem irrelevant to researchers working with mainly qualitative methods, they are required not only for automatic processing within existing and future reuse scenarios, but also for reasons of sustainability. The additional effort in creating such high quality research data has to be rewarded accordingly within a system of funding and crediting researchers which is more adequate for digital research than the current one. If reviewing existing digital resources and software were to become as obvious as reviewing the current state of the art of research, sustainability beyond single research projects or questions would become more relevant. Since the first steps in this direction have been taken by funders and other relevant organisations, now researchers need to engage directly as users in the current discussions on data quality and the further development of digital research data infrastructures. Decisions on whether and how digital resources can be reused or further developed require consideration both from a technological and a methodological perspective. Meeting user needs thus requires a dialogue between researchers and infrastructure providers to bridge the gap between discipline-specific research methods in the process of digitalisation and generic digital research data management approaches.

Funding

This research was funded by the BMBF under grant number 01UG1620G (CLARIN-D).

Acknowledgments

The article describes collaborative work, carried out within several projects at the University of Hamburg; in CLARIN-D 01UG1120G, 01UG1420G and 01UG1620G (2011–2020) and, in particular, in the projects SCHM 2585/1-1 and WO 1886/1-2 within the DFG LIS program (2011–2017).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Schmidt, T.; Wörner, K. EXMARaLDA. In Handbook on Corpus Phonology; Durand, J., Gut, U., Kristoffersen, G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 402–419. [Google Scholar]

- Hedeland, H.; Lehmberg, T.; Schmidt, T.; Wörner, K. Multilingual Corpora at the Hamburg Centre for Language Corpora. In Multilingual Resources and Multilingual Applications, Proceedings of the Conference of the German Society for Computational Linguistics and Language Technology (GSCL) 2011; Hedeland, H., Schmidt, T., Wörner, K., Eds.; Universität Hamburg: Hamburg, Germany, 2011; pp. 227–232. [Google Scholar]

- Wittenburg, P.; van Uytvanck, D.; Zastrow, T.; Straňák, P.; Broeder, D.; Schiel, F.; Boehlke, V.; Reichel, U.; Offersgaard, L. CLARIN B Centre Checklist (CE-2013-0095); Version 7.3.1, 2019-09-30; Technical Report; CLARIN ERIC: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Reichel, U.; Schiel, F.; Kisler, T.; Draxler, C.; Pörner, N. The BAS Speech Data Repository. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2016); Calzolari, N., Choukri, K., Declerck, T., Goggi, S., Grobelnik, M., Maegaard, B., Mariani, J., Mazo, H., Moreno, A., Odijk, J., et al., Eds.; European Language Resources Association (ELRA): Paris, France, 2016; pp. 786–791. [Google Scholar]

- Drude, S.; Broeder, D.; Trilsbeek, P.; Wittenburg, P. The Language Archive—A new hub for language resources. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2012); Calzolari, N., Choukri, K., Declerck, T., Dogan, M.U., Maegaard, B., Mariani, J., Odijk, J., Piperidis, S., Eds.; European Language Resources Association (ELRA): Paris, France, 2012; pp. 3264–3267. [Google Scholar]

- Windhouwer, M.; Kemps-Snijders, M.; Trilsbeek, P.; Moreira, A.; van der Veen, B.; Silva, G.; von Reihn, D. FLAT: Constructing a CLARIN Compatible Home for Language Resources. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2016); Calzolari, N., Choukri, K., Declerck, T., Goggi, S., Grobelnik, M., Maegaard, B., Mariani, J., Mazo, H., Moreno, A., Odijk, J., et al., Eds.; European Language Resources Association (ELRA): Paris, France, 2016; pp. 2478–2483. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, T. The database for spoken German—DGD2. In Proceedings of the Ninth Conference on International Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2014); Calzolari, N., Choukri, K., Declerck, T., Loftsson, H., Maegaard, B., Mariani, J., Moreno, A., Odijk, J., Piperidis, S., Eds.; European Language Resources Association (ELRA): Paris, France, 2014; pp. 1451–1457. [Google Scholar]

- Lehmberg, T. Wissenstransfer und Wissensressourcen: Support und Helpdesk in den Digital Humanities. In Forschungsdaten in den Geisteswissenschaften (FORGE 2015). Programm und Abstracts; Universität Hamburg: Hamburg, Germany, 2015; pp. 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sambale, H.; Hedeland, H.; Pirinen, T. User Support for the Digital Humanities. In Selected Papers from the CLARIN Annual Conference 2019; Linköping University Electronic Press, Linköpings Universitet: Linköping, Sweden, to appear.

- Hedeland, H.; Lehmberg, T.; Rau, F.; Salffner, S.; Seyfeddinipur, M.; Witt, A. Introducing the CLARIN knowledge centre for linguistic diversity and language documentation. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2018); Calzolari, N., Choukri, K., Cieri, C., Declerck, T., Goggi, S., Hasida, K., Isahara, H., Maegaard, B., Mariani, J., Mazo, H., et al., Eds.; European language Resources Association (ELRA): Paris, France, 2018; pp. 2340–2343. [Google Scholar]

- Hedeland, H.; Ferger, A. Towards Continuous Quality Control for Spoken Language Corpora. In International Journal for Digital Curation; University of Edinburgh: Edinburgh, UK, to appear.

- Ochs, E. Transcription as theory. In Developmental Pragmatics; Ochs, E., Schieffelin, B., Eds.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979; pp. 43–72. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, J. The Transcription of Discourse. In The Handbook of Discourse Analysis; Schiffrin, D., Tannen, D., Hamilton, H., Eds.; Blackwell: Malden, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 321–348. [Google Scholar]

- Fandrych, C.; Frick, E.; Hedeland, H.; Iliash, A.; Jettka, D.; Meißner, C.; Schmidt, T.; Wallner, F.; Weigert, K.; Westpfahl, S. User, who art thou? User profiling for oral corpus platforms. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2016); Calzolari, N., Choukri, K., Declerck, T., Goggi, S., Grobelnik, M., Maegaard, B., Mariani, J., Mazo, H., Moreno, A., Odijk, J., et al., Eds.; European Language Resources Association (ELRA): Paris, France, 2016; pp. 280–287. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, B.; Bührig, K.; Kliche, O.; Pawlack, B. Nurses as interpreters. Aspects of interpreter training for bilingual medical employees. In Multilingualism at Work. From Policies to Practices in Public, Medical, and Business Settings; Meyer, B., Apfelbaum, B., Eds.; Benjamins: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 163–184. [Google Scholar]

- Jettka, D.; Stein, D. The HZSK Repository: Implementation, Features, and Use Cases of a Repository for Spoken Language Corpora. D-Lib Mag. 2014, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, I.J.; Appleton, G.; Axton, M.; Baak, A.; Blomberg, N.; Boiten, J.W.; da Silva Santos, L.B.; Bourne, P.E.; et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for Scientific Data Management and Stewardship. Sci. Data 2016, 3, 160018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirinen, T.; Jettka, D.; Hedeland, H. Developing a CLARIN compatible AAI solution for academic and restricted resources. In CLARIN Annual Conference 2017 Book of Abstracts; CLARIN ERIC: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sloetjes, H. ELAN: Multimedia annotation application. In Handbook on Corpus Phonology; Durand, J., Gut, U., Kristoffersen, G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 305–320. [Google Scholar]

- Barras, C.; Geoffrois, E.; Wu, Z.; Liberman, M. Transcriber: Development and use of a tool for assisting speech corpora production. Speech Commun. 2000, 33, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boersma, P. Praat, a system for doing phonetics by computer. Glot Int. 2001, 5, 341–345. [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney, B. The CHILDES Project: Tools for Analyzing Talk, Volume I, 3rd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- ISO/TC 37/SC 4. Language Resource Management—Transcription of Spoken Language; Standard ISO 2462:2016; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- TEI Consortium (Ed.) TEI P5: Guidelines for Electronic Text Encoding and Interchange; Technical Report, Version 3.1.0, 2016-12-15; TEI Consortium: Chicago, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, T.; Zeldes, A. ANNIS3: A new architecture for generic corpus query and visualization. Digit. Scholarsh. Humanit. 2016, 31, 118–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yimam, S.M.; Gurevych, I.; Eckart de Castilho, R.; Biemann, C. WebAnno: A Flexible, Web-based and Visually Supported System for Distributed Annotations. In Proceedings of the 51st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: System Demonstrations; Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL): Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichs, E.; Hinrichs, M.; Zastrow, T. WebLicht: Web-Based LRT Services for German. In Proceedings of the 48th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: System Demonstrations; Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL): Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2010; pp. 25–29. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, T.; Hedeland, H.; Jettka, D. Conversion and Annotation Web Services for Spoken Language Data in CLARIN. In Selected Papers from the CLARIN Annual Conference 2016; Linköping University Electronic Press, Linköpings Universitet: Linköping, Sweden, 2017; pp. 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Remus, S.; Hedeland, H.; Ferger, A.; Bührig, K.; Biemann, C. WebAnno-MM: EXMARaLDA meetsWebAnno. In Selected Papers from the CLARIN Annual Conference 2018; Linköping University Electronic Press, Linköpings Universitet: Linköping, Sweden, 2019; pp. 166–172. [Google Scholar]

- Arkhangelskiy, T.; Ferger, A.; Hedeland, H. Uralic multimedia corpora: ISO/TEI corpus data in the project INEL. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Workshop on Computational Linguistics for Uralic Languages; Association for Computational Linguistics: Tartu, Estonia, 2019; pp. 115–124. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 | |

| 11 | |

| 12 | |

| 13 | |

| 14 | |

| 15 | |

| 16 | |

| 17 | |

| 18 | |

| 19 | |

| 20 | |

| 21 | |

| 22 | |

| 23 | |

| 24 | |

| 25 | |

| 26 | |

| 27 | |

| 28 | |

| 29 | |

| 30 | |

| 31 |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).