Abstract

Open Source Software (OSS) communities are often international, bringing together people from diverse regions with different linguistic and cultural backgrounds. National user groups can bolster these international communities by convening local events, championing the software to peers, welcoming and onboarding new contributors, raising money to support the broader community, and collecting important information on user’s needs. The open source community-led software DSpace has had great success encouraging the creation of national user groups; in the UK, North America, and Germany, the Groups have been active for many years. However, it was in 2018, thanks to a renewed focus on international engagement and more diverse representation of the global community in governance groups, that the national communities entered into a new phase: 15 new national User Groups have been formed all over the world since then, while the German user group evolved into the “DSpace-Konsortium Deutschland”, founded by 25 institutions, marking a pivotal point for membership options and National User Group participation within DSpace Governance. This article will offer an overview of the historical development of the DSpace community and its governance model, as well as DuraSpace’s international engagement strategy, including its benefits and challenges. Subsequently, we will present a case study on the DSpace-Konsortium Deutschland and explain its relation to the broader context of how to build national user groups within global communities.

1. Introduction

In 2002, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Hewlett Packard (HP) developed a solution to publish MIT’s research results on the internet. They released the software as Open Source and called it DSpace. Almost two decades later, DSpace has become the software most widely adopted for institutional repositories according to opendoar.org [1]. Early on, a relatively small group of people worked on advancing the software. An active global community of users and developers grew around DSpace as the software was adopted by many institutions.

Today, there are thousands of installations in more than 120 countries, an organizational home (LYRASIS), a governance structure and membership model that allow community members to be organized and to contribute efficiently towards DSpace’s development and enhancement.

Once the new model and the structure were in place, it was time to work on engagement and participation, especially looking at specific local user groups in countries outside the US, who were not well represented in the decision-making process. Stewarding National User Groups turned out to be one of the most successful forms of doing so. In this article, we will share how they came to exist, how they operate best and offer an example of how user consortia can enhance user participation through studying the case of the German consortium.

2. The History of DSpace Governance Structure

To gain a better understanding of the role of DSpace National User Groups and why they became important, one has to take a look at the historical development of DSpace’s Governance structure.

2.1. The Beginnings of DSpace and the DSpace Federation

The first version of DSpace was released to the public in September of 2002 as a joint effort between MIT and HP with the intention “to make its system open source and promote it to other institutions” [2]. Due to good promotion and, most importantly, to the common need institutions had at the time, it was immediately downloaded by several hundred institutions worldwide [3].

A 2003 introduction paper—DSpace. An Open Source Dynamic Digital Repository [2], already raises the question about a definition of a governance structure for the DSpace Federation:

“In 2002, MIT formed collaborative partnerships with a small number of other academic research institutions in the US, UK, and Canada, to address some specific questions such as: what will it take to successfully deploy the system at another institution? How much localization, how much customization, and how much time and effort are needed? What services can be defined to leverage the digital collections of these institutions, and how can they be implemented in DSpace? What sort of organization will the Federation become: A consortium? A new membership organization? An informal and loose collaboration? Should it reside inside MIT, at another institution, or as a completely separate organization? […] Clearly there is great need for a system like DSpace, and as we explore the definition of the DSpace Federation over the coming year, we hope to get feedback and advice from many of these institutions about how the system should evolve and how to make it sustainable beyond MIT.” [2].

The DSpace Federation Project started out as a collaboration of a small number of universities from the United States and Canada who were supposed to “act as testers, advisors, collaborators, and hopefully adopters of the DSpace platform” [3] and to figure out how well DSpace would work outside of the MIT environment.

The first User Group Meeting was held in 2004 with representatives of the participating universities [3]. In the closing statements and determinations on how to move forward, the members of the DSpace Federation also called for the definition of a governance structure for the project: “It’s time to start thinking about the long-term governance of DSpace outside of MIT or HP (e.g., the social, legal, political, economic, policy, and organizational aspects).” In [3], this shows very clearly that the community’s desire for clear structure on decision-making processes was present ever since the early days of DSpace. It does not surprise that efforts started soon after, when Julie Walker (MIT) announced the formation of a DSpace Federation Governance Advisory Board, convened “to draft a recommendation for governance and funding mechanisms to advance the DSpace community” [4]. The community of DSpace users had been growing, which called for significant change in organization. The DSpace Federation Governance Advisory Board decided to form a foundation that would be independent from both MIT and HP, to provide guidance, support and facilitate collaboration within the ever-growing DSpace community. In the report from the Advisory Board meeting in March 2006, the practical reasons for the formation of a DSpace foundation are further explained:

“It provides the corporate status that allows the community to enter into collective agreements and aids in protection from individual liability and wrongful use of the community’s assets. It, minimally, establishes an independent entity with a board of directors, a set of by-laws and other mechanisms for making decisions and guiding the project in accordance with the wishes of the community. A non-profit foundation also can play a useful liaison and coordination role between the community, commercial service providers, and the market…” [5].

For those reasons, the DSpace Foundation was formed in July 2007 and was granted non-for-profit status and incorporated in the State of Massachusetts (USA) in 2008 [4].

2.2. Founding DuraSpace

In May 2009, DuraSpace, a 501 (c) (3) non-for-profit organization, was formed as Fedora Commons and the DSpace Foundation acknowledged growing synergies between each other. In this step, two of the largest providers for managing access to digital content joined forces to pursue a common mission rather than compete against each other on the relatively small markets they catered to [6]. This move brought together over 500 organizations from around the world that were using either of the two programs. On the current history page of DuraSpace, it is stated that “By working together, both communities could be strengthened greatly through the use of shared services, lower overall operating costs, and new opportunities and capabilities for accessing and preserving digital content.” [7].

Before this event, the DSpace Foundation already counted over 350 installations [7] and organized a small sponsorship program which provided partial funding to the foundation. With this model in mind, DuraSpace launched a Sponsorship Program in 2010, asking partners and collaborators for financial support in an effort to sustain and improve both DSpace and Fedora. This program, with different sponsorship levels (Gold, Silver, Bronze) as well as a Registered Service Provider Program can be seen as the starting point of the Membership Model that is in place today.

2.3. Introducing Membership Model and Government Structures

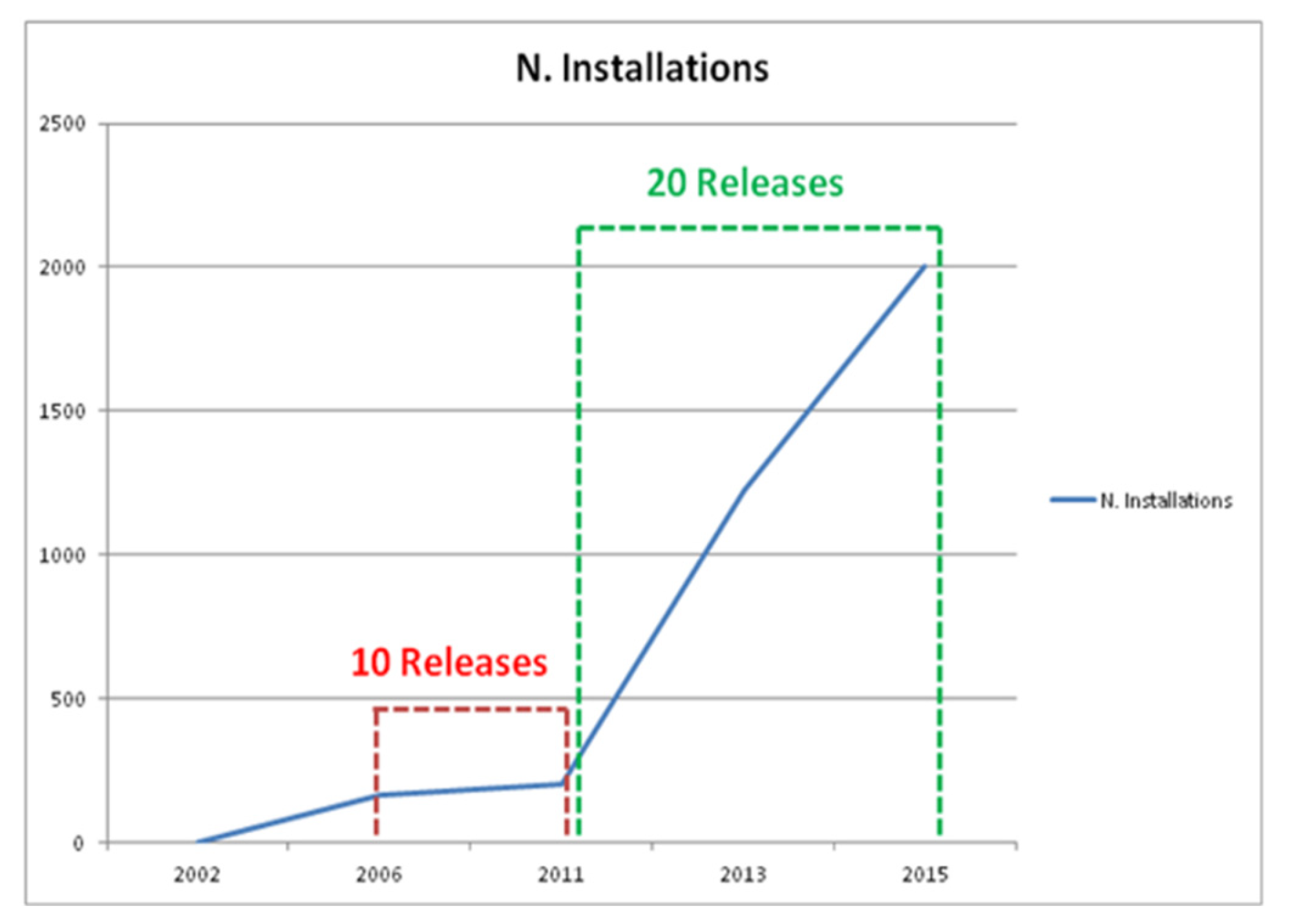

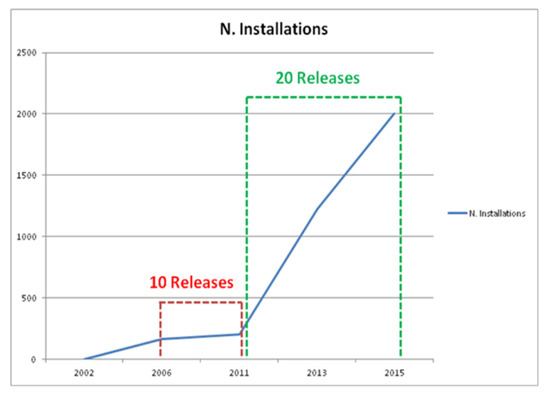

Within the first decade after DSpace was published in 2002 there have been no more than 10 releases and, as mentioned above, around 350 installations worldwide. As shown in Figure 1, the following years saw a significant increase in releases, with 20 of them being published between 2011 and 2014 alone. With the rising number of releases, the number of DSpace installations also started to increase.

Figure 1.

DSpace Releases and Installations.

In his presentation at the DuraSpace Sponsor Summit Meeting in March 2014—Membership Model and Project Governance—Overview and Framework [8]—Jonathan Markow (former Chief Strategic Officer at DuraSpace) informed the community that the number of DSpace installations had been growing from roughly over 200 installations in January 2008 to over 1500 in 2014. But other things started to change as well. With the new Sponsorship program implemented after DuraSpace was founded, a visible shift in funding happened. According to Markow, in 2009 DSpace organization was funded 100% via grants, while in 2014 only 23% of the funds came from grants, 50% from sponsorship and 27% from services run directly by DuraSpace, like Duracloud and DSpaceDirect. This shift clearly puts the sponsors at the core of DSpace’s financial sustainability. Markow sets the “Move to a Membership Model” as one of the central goals for 2014. The presentation claims that ‘sponsorship’ implies charitable contribution, which is not well-received amongst institutions. More of them are budgeted for membership rather than sponsorships. Further, Markow claims, a membership “is consistent with our move towards participatory governance” [8], the eligibility for participation in governance being described as one of the greatest benefits of a membership. With this, he is referring to the new governance model that had once again been discussed within the DSpace community and presented to the community as a rough draft during Open Repositories 2014 [9]. This model included a triangular-shaped model, with the members at the bottom. According to the model, a Leadership Group and a Steering Group would be voted from the members. One of the biggest concerns Markow addressed in the presentation was getting the community to understand this decision, without feeling threatened by it and value the benefits, as it is clear that influence would shift significantly from the community to the members.

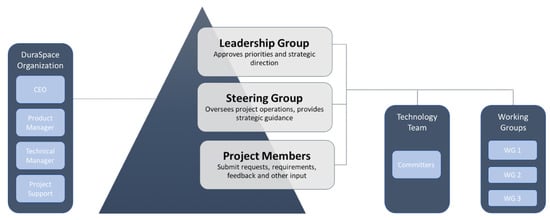

2.4. Establishment of DSpace Project Governance

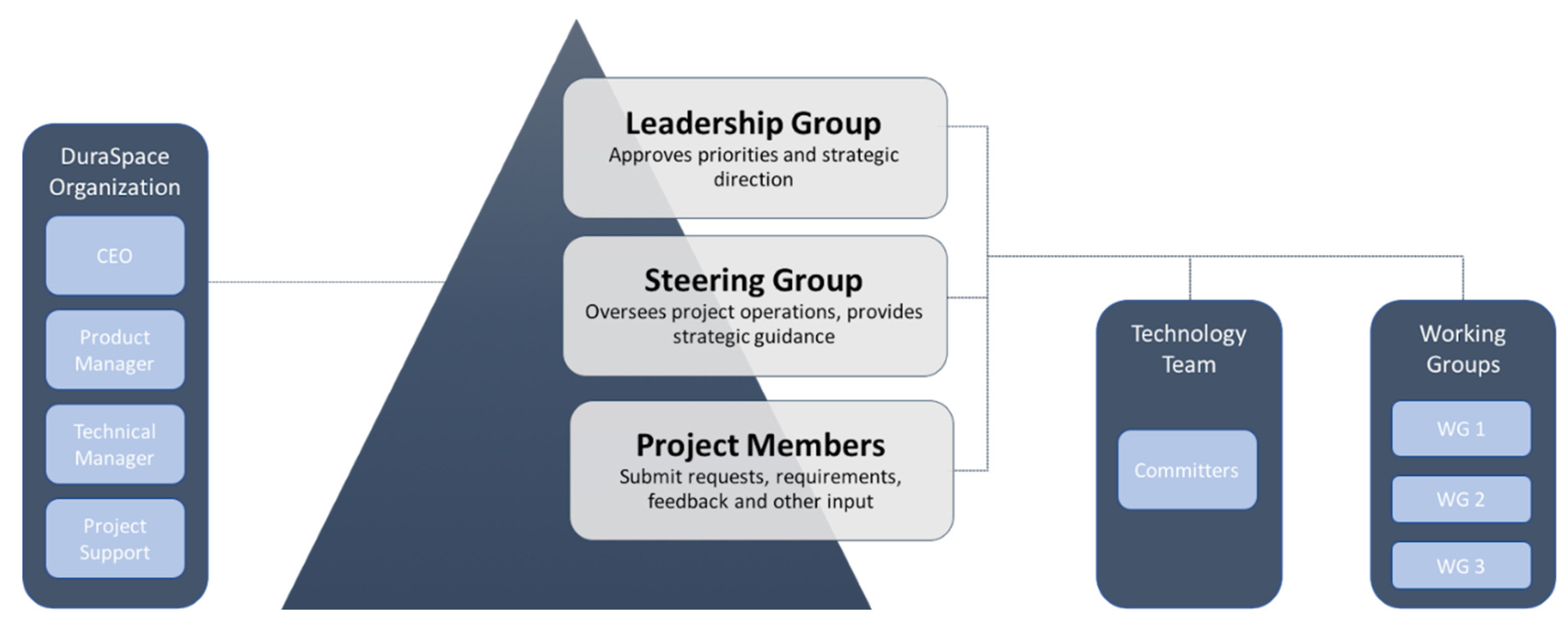

The Governance Model is based on the idea that members who contribute financially to DSpace should be able to decide how their membership money is used. Therefore, the members of the project vote representatives into the DSpace Leadership Group. This group runs all the strategic decisions for DSpace: it sets the priorities, approves budget plans, strategic decisions and technological roadmaps. While the Leadership Group is based on membership, the Steering Group is based on nominees. It has always been a responsibility of the Leadership Group to decide how and who to nominate to the Steering Group, but only in 2017 the Governance adopted a formal structure to the procedure: all nine Steerers must be nominated among the Leaders. Leaders are elected every year, while Steerers are nominated for a three-year term and every year, three of them need to rotate out or to be reelected. The Steering Group oversees the project operations and provides strategic guidance to the Leadership Group, preparing all the information needed to the leaders to make decisions. When the Governance identifies specific needs or tasks there is the option to form Working and Interest Groups. Figure 2 presents an overview about the Governance Model and all of its groups. Currently there is a DSpace 7 Development Working Group and a DSpace GDPR Working Group. A Working Group has a clear scope and should provide a tangible result. An Interest Group deals with an ongoing topic. An example would be the DSpace Outreach Working Group, that helps with marketing and public relations for DSpace [10].

Figure 2.

DSpace Governance Model.

Another important role within the Project Governance falls to the DSpace Community Advisory Team (DCAT), which is not mentioned directly in the diagram, but counts towards the Working Groups. DCAT is a group made of repository managers and other end users—in other words, those who actually work with the repositories. Often, they have a different perspective of which features might need to be added or changed within DSpace. They act as advisors for both the Committers as well as the Governance and serve as another source to gain feedback from the community and the users [11].

The Committers as the ‘Technology Team’ stand outside of the Governance Model but are in close contact with the Steering and Leadership Groups. The Committers consult to the Steering and Leadership Groups, are responsible for the source code of DSpace, reviews all code changes, and creates the official releases of DSpace. While the Steering and Leadership Group make the strategic decisions, the Committers vote before any code is changed or added to the official code base of DSpace.

To gain a better understanding of one of the major shifts that took place with the implementation of the new Membership Model and Project Governance, one has to consider the major role the DSpace Committers played in the decision-making process before. In his presentation, How to “Hack” the DSpace Community [12] by Tim Donohue (Technical Lead of DSpace at DuraSpace, now Lyrasis) identifies the Committers as the primary “Do-ers” of DSpace. He describes the Committers as a Meritocracy and Democracy (admission by merit, you have to earn your way into this group) consisting of 24 volunteer members (2014), with the authority to review and approve code, write code themselves, fix bugs (maintenance) and plan releases [12]. They were the ones responsible for the source code of DSpace and decided what would be included in the next release with a mentality of “Bring us what you have”—meaning that anyone could contribute whatever features they found interesting. The problem with this system was that releases were not put together with a clear goal in mind, as there was very little strategic planning and a larger focus on the contributions of the community.

With the growth and development of DSpace, a model that would let those who contribute financially towards DSpace participate more strongly in the decision-making process was a step in the right direction. While it appears as though this meant a loss of power for those who were responsible for the source code and did a large portion of the hard, hands-on work with the software—the Committers—this was not the case. What happened instead was that two new players—Leadership and Steering Group—were added who would focus on making strategic decisions, a role that had not existed within the community before. While the Committers shifted from being decision makers to a Working/Interest Group, they still remained the only ones who would be able to give qualified advice about the software and the source code. Thus, they are still playing an important part in the decision-making process by advising the Leaders and Steerers before any technical decisions are made.

At the bottom of the pyramid is the community itself, which includes the users and the members. They submit requests, requirements, recommendations and feedback, as well as other input. The goal of this pyramid model is to create a flowing communication process and workflow between the different stakeholders.

2.5. DuraSpace Merges with Lyrasis

In July 2019, DuraSpace merged with LYRASIS, which is now the organizational home of DSpace. LYRASIS is a 501 c 3 non-profit membership organization whose mission is to support enduring access to the world’s shared academic, scientific and cultural heritage through leadership in open technologies, content services, digital solutions and collaboration with archives, libraries, museums and knowledge communities worldwide. LYRASIS already had experience with coordinating open source community programs such as ArchiveSpace and CollectionSpace. It is the organization that developed the It Takes a Village Guidebook [13], designed to serve as a practical reference source to help open source software (OSS) programs serving cultural and scientific heritage organizations plan for long-term sustainability, ensuring that commitment and resources will be available at levels sufficient for the software to remain viable and effective as long as it is needed.

The “It Takes a Village project” (ITAV) was funded in 2017 by the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) to bring together open source programs serving cultural and scientific heritage to develop shared sustainability strategies, and to provide our communities with the information needed to assess and contribute to the sustainability of the programs they depend on.

LYRASIS has started the process of assessing all the former DuraSpace Projects (DSpace, Fedora and VIVO) using the ITAV framework, which will surely help DSpace advance. Already today, a few changes that have occurred since the merger are becoming visible in the DSpace Governance and modus operandi: LYRASIS now has a voting right in the Governance, like any other program member. This shows a strong commitment from the home organization’s side to support the long-term sustainability of DSpace.

Another important initiative is related to the support LYRASIS is providing to DSpace in terms of funding the release of DSpace 7 (through fund-raising and loan accessibility), by far the biggest release in the history of DSpace.

3. Case Study: DSpace-Konsortium Deutschland

While the Governance Model responded well to the changes that occurred within the DSpace community on a global scale, the specific situation of the DSpace users in Germany was different. Until 2010, OPUS (Online Publikationssystem der Universität Stuttgart) had been the dominating software for repositories in Germany. The software is still in use today in Germany, but the release of OPUS version 4, which was a complete rewrite of the software, resulted in a split of the community. Some users were moving to the new version, while other users continued to use the previous version 3. With the increase of DSpace installations and new releases in 2014, many members of the OPUS community switched to DSpace.

In 2014, the Technische Universtität Berlin had the idea of bringing all active DSpace users in Germany together to support an informal exchange of ideas and best practices about DSpace. Technische Universität Berlin wanted to know which other institutions in Germany were working with DSpace, what their experiences were, how they dealt with specific German problems, like certain formats required by the German National Library, and how they all might collaborate. These reasons would turn out to be the bottom line for all the different National User Groups that would be formed over the course of the following years.

The first meeting of the German User Group took place in October 2014 with approximately 25 attendees from Germany and Switzerland. The German User Group was very active since the beginning and moving forward from there, it has been growing exponentially. In 2019, only five years after the Group was established, the number of attendees in the annual User Group meeting already quadrupled, reaching more than 100 people. DSpace was now a strategic technological component in many German institutions. Therefore, the members of the German DSpace User Group wanted to be represented in the official DSpace governance and to have a voice in the strategic decisions made on DSpace. They wanted to actively contribute to the community, to secure DSpace’s long-term sustainability and its evolvement in accordance with the new needs and requirements of the global repository community.

However, the DSpace Membership structure at the time was not favorable to the German institutions, and access to the Governance was prohibitive. The German User Group’s initial idea was to combine their resources to form a consortium in order to finance a membership. That option did not exist at the time, though.

4. Listening to a Global Community

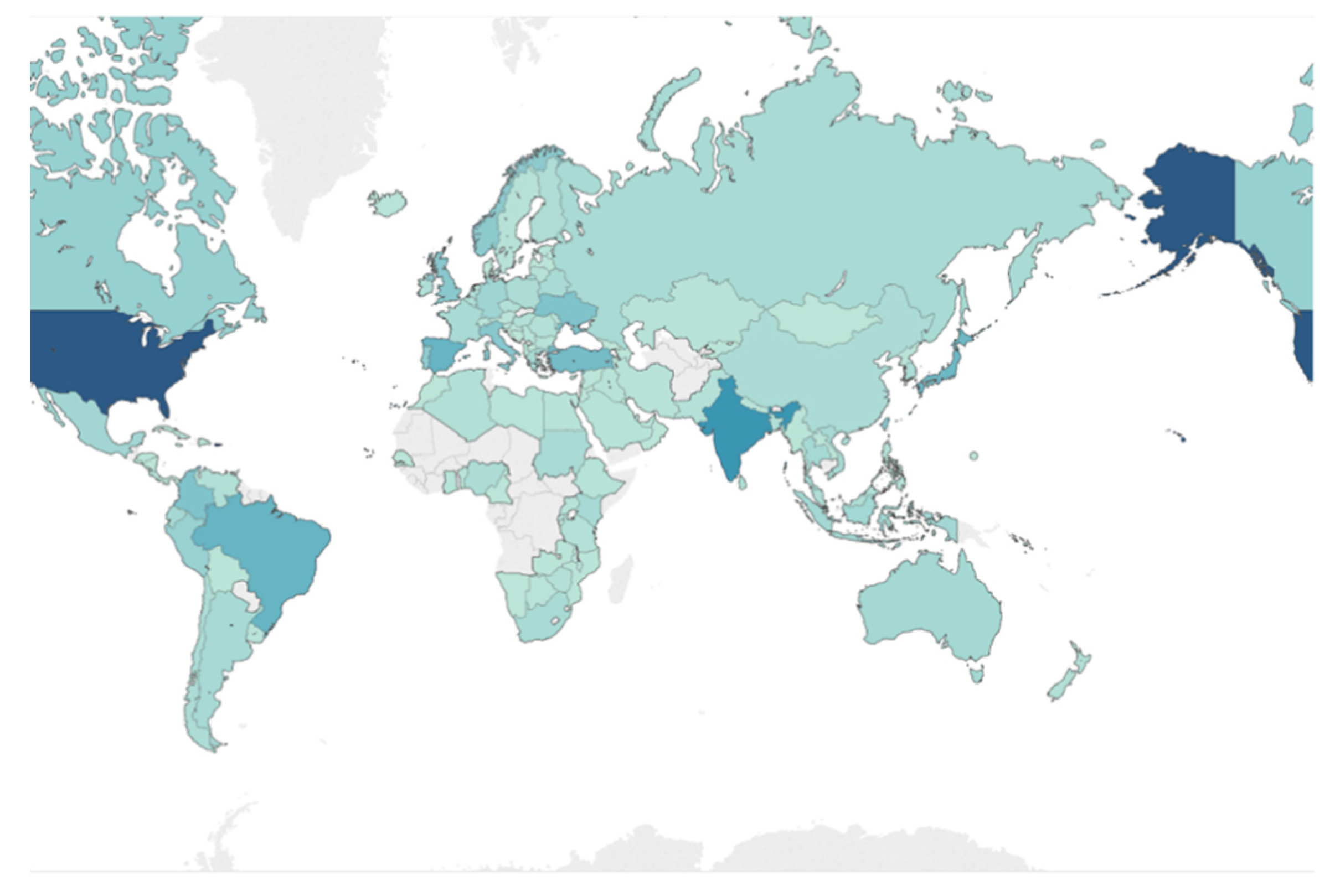

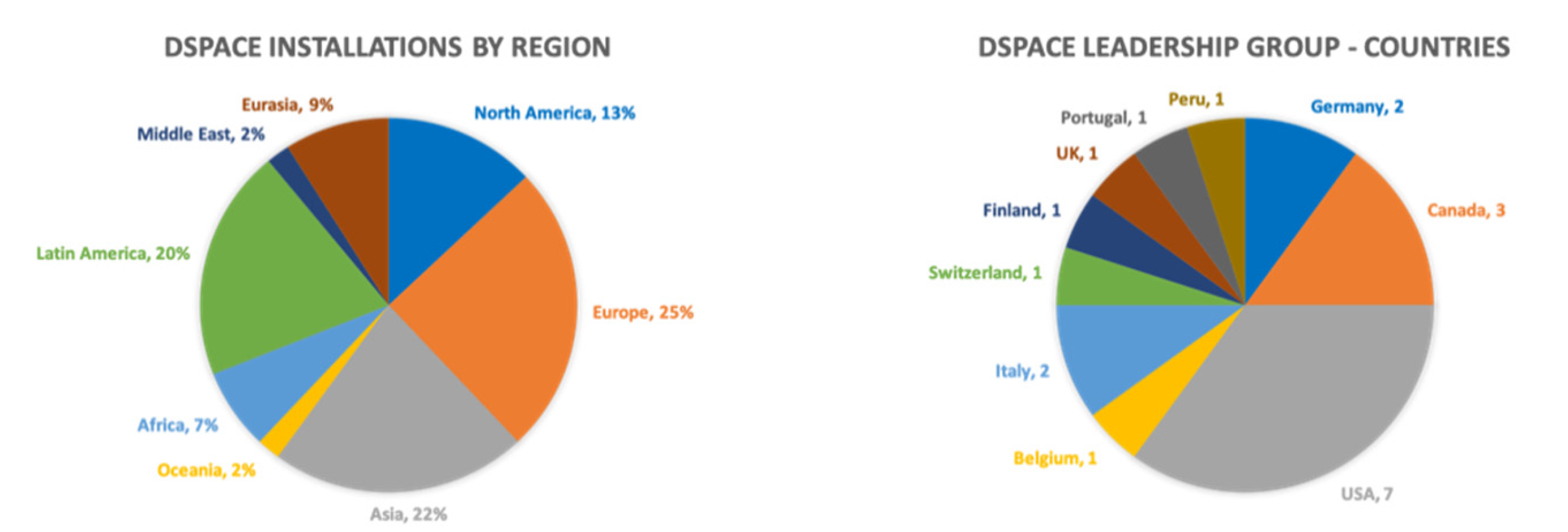

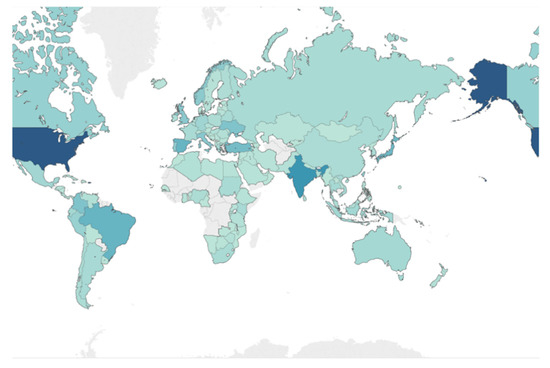

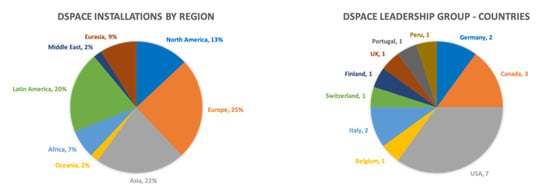

While DSpace is a global Open Source community with users in more than 120 countries [14], the governance has not always represented such an international reach, and there still are considerable gaps in global representation. Figure 3 illustrates the worldwide use of DSpace, and Figure 4 compares the numbers of DSpace installations per region with the countries that are represented in the DSpace Leadership Group.

Figure 3.

Countries that use DSpace (based on DSpace registry).

Figure 4.

Installations of DSpace per Country and representatives in the Leadership Group as of March 2020.

Consequently, the software responds to a limited set of needs and requirements, missing the opportunity to follow international trends and comply with international standards. The DSpace Governance, with the help of its organizational home at that time (DuraSpace), and now with LYRASIS support, has started to look for a strategy to strengthen the international community engagement and to collect a broader set of feedback and input. The objective is to define a roadmap that could shape the future of DSpace. One of the priorities is to better understand the needs of users in different countries.

The German National User Group (GUG) and the new commitment of its members to be more active with and supportive of the DSpace community became the natural partner for the DSpace Governance to start and test new global engagement strategies.

When the representatives of the German User Group reached out to DuraSpace with the idea of a group membership, they found someone willing to listen and interested in learning more about the local needs. On the other hand, DuraSpace had just redefined the new membership model, adding two new additional Tiers and thereby lowering the entry level for new members, which helped the formation of the consortium. Thanks to a constant collaboration between DuraSpace and GUG representatives, it was possible to define the administrative structure of the German Consortium. Another important step for DuraSpace was to open up to the possibility of accepting payments in different currencies, specifically in Euros. This step enabled German universities to incorporate their share of the membership fee into their budget without worrying about varying exchange rates on an annual basis. In that sense, DuraSpace took the risk of exchange rates on their side in order to offer the new members a fixed membership fee in Euros. DuraSpace employees traveled long distances in order to attend German User Group meetings, which was another sign of showing that they were appreciating the work done locally.

The outcome of this effort eventually came in 2018, when 25 German institutions led by Technische Universität Berlin joined together to found the “DSpace-Konsortium Deutschland”. Within the first year, the German consortium won three new members, while many other institutions showed great interest in joining. Additionally, the German institutions showed a common understanding of reciprocity within an Open Source context, highlighting the importance to give back to the community behind the software they were using, especially as it is Open Source.

Although the German consortium only applied for a Gold membership, they ended up getting a Platinum membership. This provided them with a guaranteed seat in the DSpace governance and the opportunity to be an active part of the decision-making process, while enabling them to make a substantial financial contribution to DSpace. One particular outcome of the role of the German Consortium in the DSpace governance is the GDPR Working Group, inspired and led by the German community. The work carried out by the GDPR Working Group is extremely beneficial for the whole global DSpace community, dealing with one of the most complex and articulated regulations on privacy and security that is affecting technologies worldwide. This can be viewed as a good example of how regional interests can benefit the broader global community.

5. Discussion

To have a single point of contact in Germany was (and still is) of great value for DSpace: someone who can take responsibility and is willing to coordinate the national community as well as the relations with the organizational home. One example of such an extraordinary effort in terms of self-organization is the DSpace Anwendertreffen, a meeting of the German DSpace users which they have been convening annually since 2014.

The same is valid the other way around: It was equally as important for the National User Group to have someone representing the home organization they could reach out to about any questions not specifically related to DSpace.

Open Source software lives from the idea that everyone should feel as though they are the owners. Everyone can contribute based on their capabilities, skills and resources, so that everyone can access and use what they need and they can move the technology forward together. It is not only a matter of financial contributions (even if that is crucial for sustainability), neither is it solely a matter of technical contribution. Even more, it is a matter of culture and values. Sharing know-how, experiences and best practices are all crucial aspects of open source platforms. It is a matter of perceiving oneself and being received as part of a community.

This very set of values is what DuraSpace found within the German User Group: a great community spirit; members learning from and helping each other, creating reciprocity and sharing knowledge freely. Based on the German experience the DSpace Governance in collaboration with its organizational home worked on replicating the engagement model in other regions. The objective they pursued with this effort was to listen to every single community, to recognize their efforts and the work that they are doing and, eventually, to amplify their voices within the global Community.

Over the course of the past two years, the number of members has risen from 55 to over 85 (also thanks to the German consortium) and the Leadership Group moved from 14 members representing four countries to 22 members representing 10 countries, as shown in Figure 4. This is a great effort for the aim of internationalizing the project, yet it is still nowhere near representing the actual proportions of installations per country.

To date, the majority of the members in the DSpace Leadership Group are from Europe and the United States of America, even though those are not the regions with the highest number of users and installations. This points to an immense problem, as this ratio of users to members makes it very unlikely that the needs of regions like Asia are accurately represented in the project strategic direction.

In the past, DSpace had an Ambassador program that aimed at strengthening the participation of local communities. Ambassadors were DSpace experts who had enough freedom to organize their activities with great autonomy. The program turned out to be hard to manage and, most importantly, it was almost impossible to keep track of the different activities. In order to broaden both the participation and the representation, DuraSpace (now LYRASIS) shifted the focus from the Ambassadors to National Groups. National Groups have a coordinator (an individual, an institution, a service provider) who knows the community, the language and the local community—they basically hold the role that the Ambassadors used to have in the earlier project. The main difference is that National User Groups are not single individuals, but recognized and structured communities with a wiki space and a slack channel, formally and officially representing the needs, ideas and status of a specific country. As a result, there has been a significantly higher level of participation from users outside of Europe and the US.

As of the writing of this article, there are 17 National DSpace User Groups in the following countries and regions: Argentina, Belarus, Brazil, Central America, Ecuador, Germany, Ghana, Mexico, Nigeria, North America, Peru, South Africa, Spain, Tanzania, Uganda, UK and Ukraine. Figure 5 presents a map illustrating the distribution of National DSpace User Groups worldwide. The objective behind these initiatives is DSpace’s goal to get closer to the community, to better listen to the community and to offer tools to strengthen their relationship within the community itself by providing webinars dedicated to each country. Over the course of the past year alone, 27 webinars have been organized by and for the National User Groups, reaching out to more than 3000 people in 15 different countries in five different languages. This was further possible thanks to a collaboration between DSpace and Google Scholar, that made it possible to bring webinars to a country-specific level in order to help institutions better configure DSpace and enable them to index it in Google Scholar. Another important contribution of the National User Groups is related to the Registry. The Registry is based on voluntary effort and it is not mandatory for anyone downloading and using the software to register their repository into the Registry. Based on the data it currently contains, there are approximately 2800 DSpace installations running in more than 120 countries. However, the data is not up to date and, thus, information is not completely accurate. Coordinators of National Groups have been able to collect information in their own countries and provide aggregated data to update the Registry.

Figure 5.

Distribution of National DSpace User Groups worldwide (as of March 2020).

Besides Germany, other very active National User Groups are the ones of Peru, Brazil and Mexico. The Peruvian DSpace UG hosted five webinars and several online and in-person meetings for their community, the Mexican UG hosted two webinars, while the Brazilian UG has been the most active with nine webinars and one in-person event.

Further, it becomes clear that it is very difficult for the home organization to follow up with other and new activities if the National User Groups do not have a strong local leadership. Many of the National User Groups were formed around a specific Webinar, after which nothing else has been organized. Slack channels and WIKI pages [15] for each group have been provided, but only the more active groups are actually using them. The conclusion we can take away from this is that it is hard to stimulate conversation centrally from the home organization. Instead, there needs to be a specific person from each national community, who is able to take a leadership role within the National Group. This person must be someone who has a thorough knowledge about their community’s interests and needs, while also being able to foster and nurture interim conversations. Communities who benefit from such an individual (e.g., Germany, Brazil, Peru) show astonishing results in terms of activity, communication and participation.

However, these conclusions can merely be considered the starting point of something that is currently still in the process of evolving: stimulating national and regional groups to participate in the community and to gain accurate representation in the governance is an ongoing project, with further challenges to be dealt with in the upcoming years.

6. Conclusions

The key lesson to take away from the case study is that there is no community without personal engagement. If changes are supposed to happen within the community, somebody has to do the work. Who is going to do it? The answer is very simple: any individual in the community who wants to see the change happening. Only if someone within the community is willing to go out, get things started, look for participants who share the same goal and are willing to commit, there is a possibility for things to improve and change.

There are certain perspectives that only special groups can bring to the table, as it became clear in the case study about the German consortium. Thus, it is important that interest groups within the community take a stand for themselves and actively voice their ideas and participate in finding better solutions for all. Whether they want to contribute to the software or if they just want to listen to what is going on inside the community, they should take the chance to attend open meetings and explore their possibilities to contribute. Most importantly, every user should make sure to share what they have created with the community and reach out to other users that might be willing to help or support them. This is not only the best way to make others care for the things they do, but also to contribute to the community and the software in a meaningful way.

While there is no community without personal engagement, there is also no Open Source Software without community engagement. This conclusion is key to the benefits that DuraSpace (now LYRASIS) encountered in their relationship with the German User Group. Any Open Source software depends on an active community to support and develop its enhancements. Thus, it is important for the organizations behind the software to understand that it is in their best interest to nurture and support the community; for example, by stimulating and engaging the users. However, this goal can only be reached if the organization has a clear understanding of their own values and their community. Especially if it is an international community like DSpace, it is utterly important to think and act accordingly. The same goes for dealing with local groups. There is no right and wrong, it is rather a matter of awareness. The DuraSpace (now LYRASIS) organization realized that the best they can do was to listen to what was happening in their community, to be approachable for all different kinds of users, to respect the differences between the communities, and to be open towards changes. These are important aspects not only for the organization but for the Project Governance as a whole, which is, after all, a community governance. Especially when talking about Open Source communities, being open and transparent with developments, meetings and decision making is key to a thriving community that shows a healthy level of participation. Especially for the home organization, it is crucial to act as a bridge for the different communities and to identify common needs and interest. Nevertheless, they naturally cannot be aware of everything that is going on in their community. Thus, they need their community to know how to reach out to them and to be willing to do so—and then, to listen and respond.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.-N.B. and M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, K.T. and P.-N.B.; writing—review and editing, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Technische Universität Berlin, that stepped in as a consortium leader, and is organizing the consortium on the German side. We also want to thank Erin Tripp for her help with the abstract when we submitted it to the 14th International Conference on Open Repositories.

Conflicts of Interest

Pascal-Nicolas Becker runs a company offering commercial support for DSpace and is one of two speakers of the DSpace-Konsortium Deutschland. Michele Mennielli is employed at LYRASIS (formerly DuraSpace) where he is responsible for international membership and partnership.

References

- Open Directory of Open Access Repositories. Available online: http://v2.sherpa.ac.uk/view/repository_visualisations/1.html (accessed on 13 February 2020).

- Smith, M.; Barton, M.; Bass, M.; Branschofsky, M.; McClellan, G.; Stuve, D.; Tansley, R.; Harford Walker, J. DSpace. An Open Source Dynamic Digital Repository. D-Lib Mag. 2003, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Final Report on the Initial Development of the DSpace Federation. Available online: http://msc.mellon.org/msc-files/DSpace%20Federation.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- DSpaceGovernanceHistory. Available online: https://wiki.lyrasis.org/display/DSPACE/DSpaceGovernanceHistory (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- DSpace Governance: A Report for the DSpace Federation Governance Advisory Board Meeting March 30–31 2006. Available online: https://wiki.lyrasis.org/display/DSPACE/DSpaceGovernanceHistory?preview=/19988882/21954883/DSpace_governance_report_03142006.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- Fedora Commons and DSpace Foundation Join Together to Create DuraSpace TM Organization. Available online: https://wiki.lyrasis.org/display/DSPACE/DSpaceGovernance?preview=/19006140/21954884/pressrelease.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- History Duraspace.org. Available online: https://duraspace.org/about/history/ (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- Membership Model and Project Governance—Overview and Framework. Available online: https://wiki.lyrasis.org/display/DSP/2014+Sponsor+Summit+Meeting%2C+March+11-12%2C+Washington%2C+DC?preview=/50528563/51216433/Summit-Intro-Overview-2014.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- Governance Discussion OR14. Available online: https://wiki.lyrasis.org/display/DSPACE/Governance+Discussion+OR14 (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- Project Teams. Available online: https://wiki.lyrasis.org/display/DSPACE/Project+Teams (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- DSpace Community Advisory Team. Available online: https://wiki.lyrasis.org/display/cmtygp/DSpace+Community+Advisory+Team (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- How to “Hack” the DSpace Community. Available online: https://www.slideshare.net/tdonohue (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- It Takes A Village. Available online: https://www.lyrasis.org/technology/Documents/ITAV_Interactive_Guidebook.pdf (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- The DSpace Registry. Available online: https://duraspace.org/registry/?filter_10=DSpace (accessed on 13 February 2020).

- User Groups. Available online: https://wiki.lyrasis.org/display/DSPACE/User+Groups (accessed on 3 June 2020).

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).