Abstract

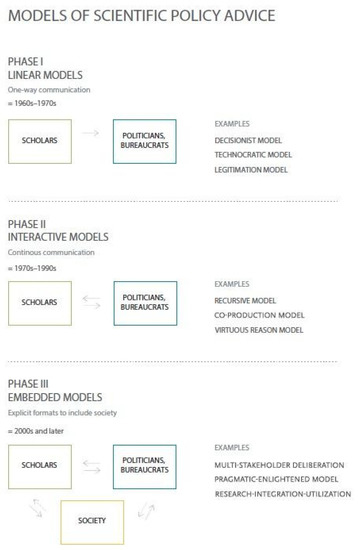

This article focuses on scholarly discourse on the science-policy interface, and in particular on questions regarding how this discourse can be understood in the course of history and which lessons we can learn. We aim to structure the discourse, show kinships of different concepts, and contextualize these concepts. For the twentieth century we identify three major phases that describe interactions on the science policy interface: the “linear phase” (1960s–1970s) when science informed policy-making in a unidirectional manner, the “interactive phase” (1970–2000s) when both sides found themselves in a continuous interaction, and the “embedded phase” (starting from the 2000s) when citizens’ voices come to be involved within this dialogue more explicitly. We show that the communicative relationship between science and policy-making has become more complex over time with an increasing number of actors involved. We argue that better skill-building and education can help to improve communication within the science-policy interface.

1. Introduction

In modern “knowledge societies”, scholarly expertise is considered a key resource for the innovative capacity of nations. It is often linked to policy-making, especially when addressing complex challenges, for example topics such as climate change, cyber-security, food safety or social security, and public health, which require deep and often interdisciplinary knowledge. The increasing demand of knowledge or evidence for policy makers can be seen in increasing investments in academic research starting from the 1960s and renewed expectations from political bodies towards research to produce applicable results [1,2]. Scientific policy-advice, in its various forms, has become a valid field of activity for scholars, and of course, one that is subject to the dynamism and complexity of global developments and changing information habits in both spheres, for academia and for political decision-makers. In this paper, we understand scientific advice to policy-making broadly as a form of communication between academia and policy-makers in government through which knowledge and/or evidence feeds into political decision-making. We also refer to a broad concept of “science”: this concept includes hard science, social science and the humanities (“scholarly activities”). The communicative relationship, of course, figures differently throughout the multitude of conceptualizations and generally in the different historical phases proposed in this article.

Of course, the increasing importance of science for society also meant that scholars themselves have reflected on the role of science in society. There has been a philosophical, sociological, and political debate about the roles of research in society, particularly in the fields of philosophy of science, sociology of science, science studies, and future studies [3]. Several, partly normative, models of scientific policy advice have been introduced, such as, for example, the “honest broker” model where scholars are expected to be impartial in their communication with political decision-makers or the “co-production” model where advice is considered to be produced in an iterative process between scholars and politicians [4,5].

An overview of theoretical models of scientific advice to policy-makers shows that among scholars there have been opposing logics and conflicting views regarding the ideal mode of communication; some of these still remain unresolved now. This paper offers a brief historical overview of the most prominent models that show how the debate has evolved across time. We conclude that the number of involved parties in scientific advice to policy-making has risen, from science operating independently to connecting with decision-makers and society at large. As all of these parties have different dynamics, perception logic, and value regimes, mutual sense-making and coordination becomes more complex. We highlight the main challenges in this respect and offer an approach to addressing and resolving the misunderstanding between scholars and other related parties when communicating. In our overview, we focus on the second half of the twentieth century, which is marked by a broad intellectual debate between so-called technocrats and decisionists and increased public attention for expert disagreements, evidence-based policymaking, and the democratization of political processes in general [6].

2. Background

In order to contextualize the topic of scientific advice to policy-makers and its role in contemporary societies, it appears important to clarify the notion of scientific policy advice as a form of science communication and point to different cultural and historical contexts that influenced its evolution.

2.1. Scientific Policy Advice as a Form of Science Communication

In this paper, we analyze communication between academic scholars and policy-making in government (referring mostly to politicians and bureaucrats). Respectively, policy-making is seen as a part of politics or political processes and comprises the activities entailed in deciding upon new policies by politicians. In modern societies, science and policy-makers are mutually dependent on each other: politics and policy rely on scholarship when aiming to address complex social problems; science at the same time is dependent on public funding and political regulatory power [2,7]. This makes it necessary for both sides to engage with each other, but “science and politics are necessarily ‘uneasy partners’ in an ‘elusive partnership’” [8].

Although it is difficult, science and policy-making need to find a way to interact with each other. The process of communicating evidence, knowledge, methodology, processes, and practices in settings where non-scholars are recognized as part of the audience can be defined as “science communication” [9]. The external “audience” in this case are policy-makers; taken together with science they represent two different subsystems with different ‘inner logics’, ‘goals’, and ‘rules’. Science is constantly searching for the truth and politics seeks to win and preserve power [10]. The place where they meet is described as “the science-policy interface”, a heterogenous, complex patchwork, where diverse interactions, interrelations, and interdependencies take place. This interface is the intersection between science and policy-making, where social processes, which encompass relations between scholars and other societal actors, allow exchange and joint construction of knowledge with the aim of enriching the process of policy-making [7,11]. Scholarly activities and knowledge penetrate non-academic contexts (e.g., policy-making) through more or less formalized science communication, a practice through which field-specific knowledge is translated into accessible, understandable information [12,13].

Generally speaking, scholars communicate with politicians and bureaucrats who transform and adjust policies under different conditions ranging from the necessity to deal with an urgent issue where political reaction is needed to the more or less bureaucratic management of long-term crises [14]. In this regard, policy-making is a mediating sphere for research to transpire into society, mostly in the form of reforms. The target group of policy-makers (at least in Western democracies) is somewhat defined—it consists of officials working in the legislative, executive, and judicial branches—but the form and format of the communicative relationship between research and policy-makers is rather ambiguous. It differs in the degree of formality (structured versus unstructured), explicitness (explicit versus implicit) and feedback (high versus low) as well as the number of addresses (one versus few versus many). Then, when communicating knowledge to politicians, scholars are not the only experts. They compete with other experts, such as, for example, political consultants, a group of professionals who have developed tools and techniques in order to elicit the support of or influence the views of the public. They occupy a critical position between the public and those who endeavor to present them and thus substantially shape the character of democratic practice [5,15]. In this paper, we focus solely on advisors who are scholars and leave out consultants.

2.2. Diverse Cultures of Scientific Policy Advice

Many diverse structures and institutions of scientific policy advice have evolved across different countries, which reflects the distinctive cultures and traditions of local decision-making [16]. Differences concern social and institutional practices by which political communities construct, review, validate, and deliberate politically relevant knowledge [4,16,17]. The most commonly used institutions across particular systems in different countries are “advisory councils”, which comprise senior scholars alongside representatives of industry and civil society; “expert committees”, which are able to address specific technical and regulatory issues in areas such as health, environment, and food safety and include mainly scholars (this distinguishes expert committees from advisory councils); “national academies”, which represent a network of academic institutions and individual scholars in a particular country and aggregate expert knowledge with the aim to communicate clear-cut messages on the science-policy interface1; and “chief scientific advisors”, which are personal advisors on science-related issues (mostly in the narrow sense of natural science) to government officials [16].

In most cases, more than one type of advisory model is involved in the above-mentioned systems. Typically, governments engage a combination of these models in order to acquire more evidence and knowledge for political processes. A rather centralized approach has been established in countries like the US, the UK, and Ireland, while other countries such as France, Germany, and other EU countries rely more on a decentralized system with a broad landscape of committees (whose scope goes beyond natural science), big national academies, and distributed sources of expertise [4,15].

Speaking less about the organizational setup and more about the individual perspective, there are four major roles that a scholar can take. According to Pielke [5], these are the “pure scientists”, who focus solely on research without considering societal relevance at all; the “issue advocate”, who according to Pielke is a scholar who aligns him- or herself with an interest group and seeks to advance this group through policy advice; and the “science arbiter”, who has direct interactions with decision-makers and focuses on issues that are relevant for policy-makers and require scientific inquiry but avoids at the same time normative questions. Finally, a scholar is considered to be an “honest broker of policy alternatives” when he or she engages in the political process by clarifying the scope of choice available to decision-makers without advocating for a special solution [4].

Despite the different national, supra-national, and cultural figurations of the science-policy interface, there is a common need to understand the role that scholars should or could play in political decision-making. This is reflected in conceptualizations of the science-policy interface, which are—despite different configurations across different countries—strikingly similar across different historical phases. Our attempt to structure scholarly discourse from the second half of the twentieth century is nevertheless most likely biased, taking into account the lines of thought of predominantly Western thinkers reflecting on Western models and Western considerations of ethics and quality.

2.3. Historical Context

Until the twentieth century, reflections on the role of scholars in policy-making were rather fragmented and non-systematic. The line of thought, however, from which contemporary science emerged, was occupied with problems of public policy. Classic figures, such as Aristotle, Plato, Smith, Montesquieu, Mill, Hobbes and Locke, Machiavelli, and Hegel, were all involved in considerations about policy-making, mostly from the point of view of the man who exercised power and needed knowledge in order to make practical decisions [18]. The debates about productive interactions on the science-policy interface can thus be traced back to the antique, when Plato reflected on possibilities to support policy decisions on correct and precise knowledge and stated that government should be in the hands of those who can access relevant expertise [19,20]. Later, Niccolo Machiavelli, who is considered one of the pioneers of modern political science, stated that experts with deep knowledge on a subject (not necessarily scholars) should be involved in the political process in order to inform political decision-making processes with truthful knowledge [21]. A fundamental change occurred in the course of the nineteenth century, when science became de-politicized.

Scholars of the late nineteenth century believed that knowledge should be acquired for the sole purpose of satisfying curiosity with no intended practical use or societal relevance. Moreover, the investigation itself was believed to represent a higher calling than the development of tools and techniques for the further utilization of knowledge [4]. In the first half of the twentieth century the concept of “pure science” prevailed and societal relevance of research was not a prominent concern, at least among the academic community. A turning point for this understanding was World War II when the development of mass weaponry entangled scientific processes and policy-making more closely than ever before [22]. The emergence and triumph of radical movements and the horrors of the Second World War were not merely responsible for fundamental scientific-ethical reflections, such as Karl Popper’s critical rationalism or Merton’s norms [23,24]. Further intellectual debates and science policies were shaped by Weinberg’s axiology of science, which recognized the importance of voicing trans-scientific questions that are “epistemologically speaking questions of fact and can be stated in the language of science”. However, “they are unanswerable by science; they transcend science”.2 Thus, policy tackles trans-scientific questions rather than scientific ones, which implies that the role of the scientist in this case must be different than in the case of dealing with issues that can be unambiguously answered [25].

After World War II the prominence of trans-scientific research increased. With the detonations of the first nuclear bombs and the acceleration of the development of science-based technology a further reflection about the societal relevance of scholarly research seemed inescapable; research was recognized as a source of change and influence throughout society [5]. These considerations sparked an inevitable conflict between the ideal of a pure scientist who is convinced that science should be separated from normative values of the political, religious, and utilitarian domains and the democratic ideal according to which no expenditure of public funds should be separated without accountability [26].

Beginning from the second half of the twentieth century (at least in post-war Europe), more and more scholars were engaged in the governmental decision-making process (directly or indirectly). What is commonly referred to as the “Sputnik shock” 3 also marked a new era of increased investments in science; since then, policy advice has been enormously expanded and differentiated [27,28]. Since the 1960s, the science-policy interface has been subject to a broader intellectual debate.

Maasen and Weingart [29] offer a framework to understanding the historical developments on the science-policy interface. They point out that several aspects of the political system have significantly changed. First, starting from the 1960s, industrialized countries experienced a general push for democratization, which led to the formation of political movements that were operating outside the system of formal political institutions but had an influence on them. One of the most prominent examples is the anti-nuclear movement, which refers to how in the late 1960s, some representatives of the scientific community began to express concern about nuclear power publicly. Later on, in the 1970s, massive nuclear power protests became an issue in Europe and North America [30,31]. In this setting, formats for broadened public participation were first created as round tables and moderated discourses. A second important development was the politicization of research, in which scholars were drawn into the political process and furthermore instrumentalized by decision-makers who tried to back their own positions with scholarly knowledge. Suddenly, uncertainty of scientific results, contradicting positions among scholars, and lack of neutrality became apparent to the general public. This resulted in a loss of authority of academic scholars [29,32]. Finally, the shift towards new forms of management resulted in new demands towards the scientific community to explain the societal relevance of their work. Knowledge production was expected to demonstrate relevance to society (social utility) and research activities came under much greater scrutiny.

3. Three Phases of Scientific Policy Advice

Along with the major historical developments discussed above, we identify three distinct phases of science policy advice in the second half of the twentieth century. We start with Habermas, who in the 1960s systematized a number of core models of how science and policy-makers can work together in his attempt to illustrate how the political system can “adapt” to the growing complexity of modern society. In his first two models this interaction is designed in a linear one-way communication process where science informs policy-makers (see “Phase 1: Linear Models“ in Figure 1). The third model suggests that both sides can work together in a pragmatic, continuous, and non-hierarchical way in order to find the best ways of addressing current social problems (see “Phase 2: Interactive Models” in Figure 1). This is referred to as the “pragmatist model” and serves a starting point for multiple spin-off concepts throughout the next decades. Finally, contemporary debates about the role of science in policy-making focus on the questions of how to engage broader society or societal groups in political decision-making (see “Phase 3: Embedded Models” in Figure 1). Each of these phases has its own logic and encompasses a cluster of similarly constructed models. In the following we will present these different phases. The rising number of involved actors in communication on the science-policy interface raises new challenges when speaking about quality: scholarly information has to be understood by politicians and the general public which do not necessarily engage in scholarly activities themselves.

Figure 1.

Models of scientific policy advice.

3.1. Phase I: Linear Models (1960s–1970s)

Starting in the 1960s, communication on the science-policy interface was mainly limited to two parties and was characterized as a dichotomy between “facts” and “values”, where science was considered the domain of “facts” or value-free, objective knowledge and policy-making the domain of “values” [3]. Communication between those two parties was seen in a linear and one-way manner: scholarly knowledge traveled from science to political decision-makers. Scientific advice to politicians was considered to be an act of rational “problem solving” or delivering evidence as well as objective facts. There are several variations of linear models which embody different hierarchies in which scholars and politicians find themselves: decisionist (“politics first, then science”), technocratic (“science first, then politics”), and legitimation (“science for the purpose of politics”) models. As mentioned in the previous section, these were systematically reflected upon by Habermas but have their roots earlier in the twentieth century [19,33,34].

The decisionist model dates back to the work of Max Weber in the late ninenteenth century [19,35,36]. It presupposes a strict and clear division of activity and responsibility between science and government. According to Weber, scientists are able to make policy-making more rational but they should remain “clean” of normative-ethical judgements, which are subjective and thus cannot be made in a rational manner [35,37]. Research plays a supportive role for political decision-makers and is meant to deliver “sound” advice and facts being isolated from values and interests which are dealt with solely in the political domain. Determining policy ends or designing political pathways necessarily requires “subjective” normative-ethical judgements which cannot be made in a rational manner and thus cannot or even should not be made by scholars [34].

The decisionist approach was criticized and reflected upon by Saint-Simon and Bacon [33], who in turn introduced the technocratic model (“science first, then politics”), which claims that politicians actually play a secondary role and can be replaced by experts who base their decisions on ‘sound science’. This model presupposes that policy-making can be left to those who have the expertise and bureaucrats without the need to involve value-laden considerations. Political responsibilities should thus be delegated to impartial scientific and technical experts. These experts are deemed to be qualified enough to replace government officials with partial biases, ignorance, and vested interests [38]. Accordingly, experts should determine policy goals and set the political agenda while other societal groups (e.g., civil society) are incapable of making meaningful contributions and can therefore be excluded from designing the political agenda. In this constellation, the role of politicians is reduced to generic decision-making in precisely those cases where scientific rationalization does not yet provide solutions. Political decision-making is thus value-free [37].

Close to the technocratic idea and which emphasizes the key role of research in the political process is the legitimation model. Described by Habermas in the 1960s [39], it acknowledges the authority of experts and their stake in decision-making, but unlike in the technocratic model, experts are not involved in decision-making and are rather only “selected” when necessary by policy-makers. This proceeds from the assumption that policy-making in government can make use of the authority that science enjoys in public for justifying political actions. This kind of advice cannot be regarded as value-free and objective; it may be contextualized with the aim to support (already made) political views and decisions. Contrary to the technocratic model, the legitimation model suggests that scientific reasoning is value-laden [8].

Another example of a linear model is the “red book model”. Starting in the 1970s, it introduced a structured format in which scientific policy advice could be provided to the government which abided by linear logic. Communication on the science-policy interface was seen as a two-stage process, involving both “risk assessment” and “risk management”. In the first step, scientific experts act independently from any political considerations and aim to provide policy recommendations on the basis of purely scientific deliberation. In the second step, policy deliberations begin once scientific experts have completed their deliberations. This two-step-process is designed so that policy-making cannot influence science, thereby adhering to the two disparities of the two domains.

3.2. Phase II: Interactive Models (1970s–2000s)

The general democratization of government (see Section 2.3) placed political decision-making under more public scrutiny: politicians had to explain their actions to a broad public who was influenced by them and research was expected to produce solutions to societal relevant problems. Linear models failed to meet these requirements, mostly because they presuppose that science and policy-making will act in isolation from each other, which does not allow non-academic parties to decide on research questions and adapt them to societal relevant issues.

In response to this line of thinking, linear models were replaced in the literature by “interactive” alternatives (Phase II). These models presume that the process of producing scientific facts and policy judgement cannot be completely separated from each other. Politically relevant knowledge is developed in a continuous interaction between scientists, policymakers, and societal actors. This refers to problem formulation in research as well as the formulation of goals and means. Jasanoff contends that humans seek to confront facts about the natural world with problems of social authority and credibility [8]. Habermas describes interactive knowledge by introducing the concept of the pragmatist model, which states that scholars are not able to deliver “absolutely true” and value-free knowledge but should still provide useful judgements and evidence about policy ends and means [39]. This model served as a basis for multiple spin-offs and interpretations among thinkers. A part of these spin-offs will be briefly discussed below, as in, e.g., the recursive model [40], the co-production model [41], and the virtuous reason model [22], a part of which will be briefly discussed below.

One of the first interactive models was introduced by Weingart, and this was the recursive model, which states that interactions on the science-policy interface are not unidirectional but rather can be seen as a continuous process in which scholars reach out to politicians in order to communicate scientific results and problems to them [42]. There are at least two points of interaction between these sides: firstly, scholars can act as agenda-setters for the political domain; secondly, politicians can seek the support of research in order to legitimize their decisions for a broader public. Weingart does not see science and policy-making as merging into one another, since this would be accompanied by a dissolution of the functional differentiation between the two systems. However, conflicting research that does not support the politicians’ views can intentionally be left out.

Jasanoff structures the “untidy, uneven processes through which the production of science and technology are entangled with social norms and hierarchies” and builds the theoretical case for the concept of co-production. In her view, natural and social orders are produced together. New scientific findings in fields which are relevant to society (e.g., legal frameworks for gene modified organisms and ethical norms for the application of artificial intelligence) require a specific restructuring of social order. Thus, newly generated knowledge is becoming an element of political activity that feeds into political decision-making. Interactions between relevant parties on the science-policy interface undergo parallel processing with ambition to solve problems in either domain: nothing significant in science happens without concurrent adjustments in society, political activity, or culture, and vice versa, and dealing with societal problems adds to the existing corpus of knowledge [4].

The idea of co-production was widened in another model also conceptualized by Jasanoff—the virtuous reason model [22]. Here, she also assumes that knowledge production is intervened with by political activities and that these domains do not function separately. At the same time, she speaks of a means to connect politicians and scholars; for this, she introduces a new actor, namely intermediaries, who are experts who act on the interface between policy-making and science and have to find a way to communicate and translate scientific knowledge to political decision makers. They have the task of linking scientific knowledge with matters of social importance to relevant societal groups; they are guided by different ethical social considerations and their main function is to connect scientific knowledge with societal challenges, diagnose public problems, and develop appropriate solutions and means for their implementation.

3.3. Phase III: Embedded Models (2000s until Now)

Starting already from the 1970s, policy-makers found themselves under increased scrutiny from broader society. From this time on, discussions between scientists and politicians on contradictory topics, such as nuclear power and environmental challenges, were brought into the public sphere and exposed all contradictions and uncertainties of an academic and political debate to the public. This resulted in a changing perception of science among the public: science seemed uncertain and incomplete rather than a source of finite answers to complex problems. In this setting, not only did political decisions have to be explained to society at large, but scientists and science were also held accountable for public expenditure allocated to research and had to uncover their work [29]. By the end of the 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s the debate around ways to set up mutually comprehensive communication between policy-makers, scholars, and different societal actors evolved. Phase III is marked by the attempt to find an adequate mode of communication with different societal actors without compromising on quality and political robustness advisory knowledge.

Conceptually, these models can still be located among the pragmatist approach (see Section 4.2) introduced by Habermas, as they regard scientific policy advice as a discursive process between relevant actors. Nevertheless, we consider the embedded phase separately. Other than during the interactive phase (Phase II), this phase is characterized by intensified reflections about formats of societal engagement and the language of communication on the science-policy interface. Public participation was seen as a measure to solve chronic dilemmas of policy-making due to a lack of public trust in expertise, and it empowered citizens to have a say in decisions that influenced them [29].

The changing nature of interactions between universities and a larger society was conceptualized even earlier (in the mid-1990s) by Etzkowitz and Leydersdorff [43,44] in the triple-helix model that analyzes business innovation processes. Similarly to the interactive phase, the triple-helix model presumes that knowledge production changed from linear interactions between universities “on the supply side” and industrial actors (e.g., corporations) on the demand side to interactions within multi-faceted networks which include reciprocal and ongoing interactions between all parties. These networks include close communication between industry, government, and academia, who previously operated rather at a distance from one another. As a result, institutional boundaries were transcended to create new innovation environments as well as new inter-organisational and interdisciplinary discourses [2,3,44]. Such networks are shaped by three functions: organized knowledge production (academia), economic wealth creation (industry), and reflexive control (government and politics) [45]. The dynamic of such networks is dependent on the development of communicative competencies that are necessary to establish a mutual understanding between all related actors; in turn, their communication can be intensified by information and communication technologies [46]. As mentioned, the triple-helix model mostly deals with business innovation processes. Nevertheless, the basic concept of bringing together actors with different dynamics and logics to find an optimal format for communication can also be extrapolated to other societal groups or society at large.

Models of scientific policy advice from Phase III mostly deal with the following questions: How can the public be meaningfully involved? How can we ensure that public interest and values enrich and do not replace expert knowledge? Edenhofer and Kowarsch [37,47] introduced the pragmatic-Enlightened model (PEM), which refines existing pragmatic models of scientific policy advice and aims to make consulting policy more relevant to society. It adjusts the classical pragmatist approach by stating that several policy pathways should be outlined by picturing their practical consequences. Moreover, it explicitly draws up a framework that according to which a broad public debate about these selected pathways should be ensured. It is up to societal actors to decide which pathways are relevant to them.

Breeman et al. [45] introduced multi-stakeholder deliberation platforms, which are a mechanism to gather diverse stakeholders from the domains of policy-making, science, and society around one problem and to develop common scenarios. Multi-stakeholder platforms at the science-policy interface include new forms of knowledge production in light of complex societal challenges and thereby attempt to conceptualize opportunities for a meaningful inclusion of stakeholders in political decision-making [46,48,49]. Then, deliberation platforms can improve the communication and mutual understanding between different stakeholders who tackle common policy problems.

Krott and Böcher [47] attempted to illustrate “real-world” interactions between science and policy-making step by step and introduced the research-integration-utilization model. Following pragmatist logic, they assumed that scientific advice cannot be produced autonomously and in a way which is completely value-free. Different interest groups are involved and interact on the science-policy interface; quality control can thus not happen according to the rules and practices of only one group. In this sense, Krott and Böcher try to reconcile these interest groups and describe a set of conditions according to which knowledge transfer can occur ideally. This involves a compromise between all groups to ensure that scientific policy consulting is epistemically sound, politically applicable, and democratically legitimated. To achieve this, scientific policy advice is divided up into three different activities: research, integration, and utilization [50]. Research herein is understood as a process that produces a specific form of knowledge by using scientifically accepted principles, methods, and standards (similar to the concept of “fact production”) [4]. During the integration step research questions are directed to a practical problem with the aim of backing it up with the necessary expertise, e.g., risk assessment or offering a possible solution scenario. Here, a number of new actors come into play, such as political actors and intermediaries but also representatives of civil society who might have a say. Integration brings together different actors across the science-society interface, including political decision-makers, scholars, and civil society representatives who have a say in this. At this point, mutually comprehensive communication is of key importance, as all actors may have different perspectives and expectations. In the end, political actors filter out knowledge and expertise that is useful for their policies (utilization). From this point, deliberation that involves multiple actors is over and the formulation of the final decision is left to the political actors. A key point is that all activities happen simultaneously in a constant process of adjustment, not one after another. This implies that scholars are constantly adjusting research questions to the demands of other societal actors with whom they are in contact during the integration stage.

4. Discussion: Quality of Communication on the Science-Policy Interface

In the following section we will analyze how the above-described models of scientific policy advice build on each other, outline which problems remain throughout their evolution, and delineate current challenges to scientific policy advice. We draw attention to mainly three aspects: the constellation of actors on the science-policy interface, their expectations towards knowledge production, and communication practices as a prerequisite to achieving mutual understanding.

4.1. Phase I: Epistemic Soundness

In the second half of the twentieth century the necessity of knowledge and evidence produced by scholars somehow needing to feed into policy-making became clear. At that time the scientific process (“fact production”) was considered to be separated from political “decision-making” [4]. Despite some crucial differences concerning the division of responsibilities in the process of scientific policy advice in the decisionist and technocratic interpretations, linear models share the common procedure of advising. This is characterized by an institutional separation of science from policy-making and the isolation of “fact-production” from value-laden normative considerations that are necessary for political decision-making. Advisory knowledge is thus created either apart from or prior to political decisions. Science is prone to guarantee quality and integrity of its outcomes on own terms. Deviations from this sequence of steps can infringe on the potential of science to deliver objective information about the world. It is assumed that scientific quality can be evaluated by applying the usual set of criteria that the scientific community holds: peer-reviewed outputs, reproducibility, and openness to scientific debate [22]. Afterwards, “pure results” which are epistemically sound are communicated to stakeholders outside of academia (again, from an ideal perspective).

The rules of science can be considered suitable for use by scholars to communicate with each other and build mutual understanding. However, most non-academic audiences are not necessarily trained in science and do not understand its processes (which is very much shaped not by finding the truth, but by falsifications of old(er) knowledge) and logics (scepticism). Furthermore, politicians often have to deal with problems where final scientific facts cannot be presented [25]. Policy-makers do not like this insight. Many practical problems require the understanding of multiple disciplinary perspectives, which is difficult to grasp without having insight into every one of the related disciplines; thus, policy-makers inform themselves from secondary information sources such as media reports [51]. Scholars, on the other, are detached from other societal fields such as policy-making and might miss topics relevant for politicians. The same works the other way around: if the academic perspective is not included in political agenda-setting, decision-makers might simply not be aware of important issues where action is needed [19]. Finally, quality assurance in research as well as complex translation practices between science and policy-making could simply take too long with regard to properly addressing problems that are on the political agenda which need a fast reaction. This leads to a dissonance of outputs and procedures when bridging knowledge, evidence, and political decision-making.

4.2. Phase II: Political Robustness

Envisaging these problems, the debate shifted towards interactive models of scientific advice (Phase II). The communication process was reconsidered and remodeled in order to ensure that knowledge and evidence reached policy-makers while their agenda was adjusted to in multiple recurring interactions. The concept of scientific isolationism, which suggested that research operates in isolation from society and should consider only epistemic values, became outdated [3]. Actual engagement of scholars in advisory roles urged them to take new values into account.

Values such as building an additional layer of expectations on top of those that are established in the scholarly community were held. Advisory knowledge was supposed to meet sets of standards from the scientific and political domains: it had to be epistemically sound (science) and politically robust (policy-makers), meaning that it had to be produced in a scientific manner, address societal challenges, and fit into contemporary decision-making mechanisms. Butter [52] defines concrete criteria that punctuate the expectation for scholarly knowledge to be “politically robust”. He suggests that the following aspects should be taken into consideration: (a) accuracy of implementing scientific knowledge in a policy plan; (b) incorporation of knowledge from politicians and stakeholders in this knowledge-based policy plan; (c) transparent debate with external stakeholders on possible outcomes; and (d) discussion about whether policy measures sufficiently fulfill preferences or best interests of all related stakeholders. This approach links scholarly activities to political activities such as political planning, discussions, and conflicting views.

Science focuses only on evidence and facts, not values. However, considering that decisions in politics are never free of values, they come into play automatically and involve scholars, whether they like it or not [53]. When performing scientific advice, as Douglas [53] suggests, scholars must consider the possible consequences of errors in their work and especially in their prognoses. Uncertainty in research is inevitable and a transparent and decent communication of limits of scientific discovery can help to inform the public truthfully about scientific discovery. Wagner [54] claims that scholars could benefit from being particularly taught about ethical principles that are necessary to apply when consulting on political matters and policy issues. If possible, only empirically tested theories should be communicated to external audiences. If this is not possible, this should be voiced explicitly and transparently. This approach could undermine the main ethical problem in science communication—overestimation and overinterpretation of results [55]. Decent communication depends extensively on the self-discipline of scholars, and teaching them about the dangers of misinterpretations and overestimation could raise awareness about possible consequences in science communication.

Interactive scientific policy advice models went a step further in describing real-world policy processes, showing that knowledge is produced in a continuous interaction between scholars, politicians, and citizens. Furthermore, models of Phase II make it clear that epistemic soundness is not the only quality dimension that applies on the science-policy interface. Knowledge and evidence are expected to be politically robust (offer solutions to actual problems) and at the same time ethically adequate (be considerate about consequences).

4.3. Phase III: Public Legitimation

In Phase III a third layer of expectations comes into play: the need to preserve public legitimation. Rising public attention towards policy-making and a rising interest towards the role of science in decision-making brought about a new challenge: society at large expects to be informed and engaged in decision-making [29]. Different spin-offs of the pragmatist models (Phases II and III) build primarily on Habermas’ concept of deliberative democracy and suggest that political decisions should be a product of fair and reasonable discussions among society members [34]. According to this logic, it is not acceptable for a minority elite (scholars or politicians) to impose their own values on the general population without previous consultations with this population. Public engagement, in this respect, makes communication on the science-policy interface more just, but also more complex.

A logical precondition for societal actors to engage in discussions on the science-policy interface is to be informed about the status quo and to understand it. The public can inform itself on scientific topics through different channels: the media, outreach-events by academic institutions, cultural events, and other channels. Such spaces and formats for science and society interactions have grown significantly in recent decades, in addition to the amount of scientific news. Communication through the media can be used as an example to illustrate the problems that arise in this respect between scholars and the public. Several studies about the relationship between academia, the media, and the public almost in unison portray scholars as being unsatisfied with the way their output is communicated to the public; they criticize inaccuracies and incomplete representation of their work. In turn, journalists claim that scholars lack basic understanding of the journalistic process and the communication skills necessary to explain their work to the public. Scientists argue that oversimplification and the inability of the public to distinguish between good and bad research is a crucial problem [56].

An example of such a communicative deficiency is science communication on medical research. This involves scholars who do research on medical topics and whose work has an undisputable societal impact, for example when it comes to treatments. Most patients and even doctors, however, lack sufficient statistic literacy, so they are unlikely to understand the numbers they encounter in medical research. On the other hand, most attempts to present this information in a simplified way—on web sites and in leaflets, for example—often report evidence in a non-transparent form. Science communication is not accurate in this setting: research does not necessarily succeed in supplying societal actors with knowledge and evidence but instead offers a fruitful ground for misinterpretations when reporting evidence in non-transparent forms that suggest big benefits of featured interventions and small harm [57].

Public legitimation expected to be preserved in line with Habermas’ concept of deliberative democracy is not possible if the public does not understand how decision-making comes into being and what evidence it is based on. Models of Phase III set up an important precondition for dialogue between scholars, policy-makers, and society by bringing all actors together; new forms of collaboration are conceptualized (PEM and multi-stakeholder platforms) as well as with guidelines for organizing interactions on the science-policy interface (the RIU model). At the same time, creating a space for dialogue does not necessarily grant the competence for actors to understand each other.

5. Education as a Possibility to Improve Science Communication and “Policy Advice”

Throughout the second half of the twentieth century the debate about scientific policy advice and its values, roles, and boundaries has changed enormously. It started with a highly conceptual discussion about the mode in which knowledge should travel in a linear manner from the scientific into the political domain (Phase I). Phase II was marked by the insight of multidirectional communicative processes. Phase III has been characterized by the aim to include broader society within the discussion of the knowledge transfer process between academia and policy-makers, but also by a hands-on discussion about how to design this advisory process and identify optimal frameworks in which these workflows would work. It is evident that the number of stakeholders engaging in the science-policy interface increased throughout Phases I, II, and III. From a rather isolated sphere, scholars became more and more entangled with society and proving the relevance of their activity, first by interacting with policy-makers and then by being bound to increased societal scrutiny. Research outputs had to be explained in a manner understandable not only to peers but also audiences that were not exposed to this kind of knowledge in depth.

Building on the overview of different models of science communication and their evolution throughout recent decades, it is evident that the constellation of actors has changed in academic debates. Starting from science and policy-making as two isolated subgroups with minimal interaction we get to concepts that presuppose continuous interaction, co-creation, and even legitimation through informing and engaging broader publics. Still, despite the attempt to bring together all relevant actors, science communication is sometimes impeded by mutual misunderstanding [56,58]. This mishap could be addressed by improved education, i.e., by improving communication skills among scholars and competencies to recognize good scientific practices within society.

In this sense, scholars could benefit from learning how to speak to societal actors (e.g., politicians or civil society and bureaucrats) already in the early stages of their careers [58]. This could help them to understand the potential consequences of overestimating one’s results and prepare them for value-laden discussions that naturally arise when involving politicians and citizens. Furthermore, at this point scholars could be sensibilized to basic ethical “rules” and learn how to present their work in a more responsible and transparent way. Key to this are such basic manifestations that only empirically tested theories are safe to communicate to the outside world and that if this not possible it should be clearly mentioned [58]. Uncertainty of research results or conflicting views are an indispensable part of research and thus also of transparent science communication. Resting on ethical values when speaking to the outside world brings scholars closer to the “honest broker” model as described by Pielke [5].

Politicians, bureaucrats, and the general public, in turn, could be trained to understand the process of scientific discovery better and that this is an ongoing debate with recurring questions and no finite answers and uncertainty is an indispensable part of it [8,29,57]. Furthermore, the general public could be taught how to understand and categorize communication about scholarly outputs (e.g., distinguish an empirically tested theory from one which has not been empirically tested). Among competences that could help society to understand science is, for example, statistical literacy, which is according to Gigerenzer an important precondition to understanding research in a society which is increasingly influenced by technological and scientific innovation [58]. Such competences and skills could be fostered directly from primary and secondary school education. All in all, when looking at models of scientific advice to policymakers we can state that communicating science effectively does not come easily; it is an acquired skill for all parties at the science-policy interface.

Author Contributions

N.S., G.G.W. and B.F. defined the research questions. N.S. studies and selected the literature and composed a first draft. Afterwards, the paper was written and revised in several iterations among B.F., N.S. and G.G.W.

Funding

This research was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. Grant number: 01PW18008A.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Conraths, B.; Smidt, H. The Funding of University-Based Research and Innovation in Europe; European University Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lentsch, J.; Weingart, P. Scientific Advice to Policy Making in Comparative Perspective: Technocracy Revisited—Introduction. In Scientific Advice to Policy Making, 1st ed.; Lentsch, J., Weingart, P., Eds.; Verlag Barbara Budrich: Leverkusen, Germany, 2009; pp. 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Himmelsbach, R. Playing Second Fiddle: Expert Advice and Decision-Making in Switzerland. Doctoral Thesis, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland, June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jasanoff, S. States of Knowledge: The Co-Production of Science and the Social Order; Routledge: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pielke, R.A., Jr. The Honest Broker: Making Sense of Science in Policy and Politics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Botterill, L.C. Evidence-based policy. Oxf. Res. Encycl. Politics 2017. [CrossRef]

- Faehnrich, B.; Ruser, A. ‘Operator, Please’—Connecting Truth and Power at the Science-Policy Interface. J. Sci. Commun. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, G.; Letsch, J.; Weingart, P. Quality control for the leading institutes of economic research in Germany: Promoting quality within and competition between the institutes. In The Politics of Scientific Advice Institutional Design for Quality Assurance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, S.R.; Horst, M. Science Communication: Culture, Identity and Citizenship; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann, N. Die Wissenschaft der Gesellschaft; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt, Germany, 1992; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- van den Hove, S. A rationale for science—Policy interfaces. Futures 2007, 39, 807–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machin, A.; Ruser, A. What counts in the politics of climate change? Science, scepticism and emblematic numbers. In Science, Numbers and Politics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 203–225. [Google Scholar]

- Fischhoff, B. The sciences of science communication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 14033–14039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD Science. Scientific Advice for Policy Making: The Role and Responsibility of Expert Bodies and Individual Scientists; Technology and Industry Policy Papers No 21; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sheingate, A. Building a Business of Politics: The Rise of Political Consulting and the Transformation of American Democracy; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wilsdon, J.; Allen, K.; Paulavets, K. Science Advice to Governments: Diverse Systems, Common Challenges. In Proceedings of the Auckland Conference, Auckland, New Zealand, 28–29 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, C.A. Civic epistemologies: Constituting knowledge and order in political communities. Sociol. Compass 2008, 2, 1896–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shils, E.A. Social science and social policy. Philos. Sci. 1949, 16, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millstone, E. Science-based policy-making: An analysis of processes of institutional reform. In Wozu Experten? Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 314–341. [Google Scholar]

- Millstone, E. Technology assessment policy—Making framing assumptions explicit; IAS-STS-Yearbook-092; IAS-STS: Graz, Austria, 2009; pp. 291–310. [Google Scholar]

- Beckstein, M. Machiavellis Der Fürst: Die Rezeption vor der Publikation (1513–1532). ZPTh—Zeitschrift für Politische Theorie 2013, 4, 66–79. [Google Scholar]

- Jasanoff, S. Quality control and peer review in advisory science. In The Politics Of Scientific Advice: Institutional Design For Quality Assurance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- Popper, K. The Logic of Scientific Discovery; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R.K. The Sociology of Science: Theoretical and Empirical Investigations; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, A.M. Science and trans-science. Minerva 1972, 10, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, G.H. The pure-science ideal and democratic culture. Science 1967, 156, 1699–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinrichs, H. Advisory systems in pluralistic knowledge societies: A criteria-based typology to assess and optimize environmental policy advice. In Democratization of Expertise; Springer: Dordrecht, Germany, 2005; pp. 41–61. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, N. Overall Eu R&D Spending Continues to Rise, Despite Falling Public Investment, 2018. Available online: https://sciencebusiness.net/news-byte/overall-eu-rd-spending-continues-rise-despite-falling-public-investment (accessed on 11 November 2019).

- Maasen, S.; Weingart, P. Democratization of Expertise? Exploring Novel Forms of Scientific Advice in Political Decision-Making; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; Volume 24. [Google Scholar]

- Garb, P. Critical Masses: Opposition to Nuclear Power in California, 1958–1978, by Thomas Raymond Wellock. The University of Wisconsin Press, 1998. Reviewed by Paula Garb. J. Political Ecol. 1999, 6, 123–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Moxon-Browne, E. Anti-nuclear movements: a world survey of opposition to nuclear energy. Int. Aff. 1992, 68, 164–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimber, B.A. The Politics of Expertise in Congress: The Rise and Fall of the Office of Technology Assessment; Sunz Press: New York, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Goode, L. Jürgen Habermas: Democracy and the Public Sphere; Pluto Press: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, M. Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft: Grundriss der Verstehenden Soziologie; Mohr Siebeck: Tübingen, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Winckelmann, J. Max Weber—Das Soziologische Werk. In Politologie und Soziologie; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1965; pp. 341–388. [Google Scholar]

- Schenuit, F. Zwischen Fact-Und Sense-Making: Die Be-Deutung Wissenschaftlicher Expertise im Politischen Entscheidungsprozess; Impulse für die Politikwissenschaft aus den Science and Technology Studies; Regierungsforschung.de: Duisburg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kowarsch, M. Prevalent Action-Guiding Models of Scientific Expertise in Policy. In A Pragmatist Orientation for the Social Sciences in Climate Policy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 81–100. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, W.N. Public Policy Analysis; Routledge: New York, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. Technik und Wissenschaft als ‘Ideologie’? Man World 1968, 1, 483–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingart, P. The moment of truth for science: The consequences of the ‘knowledge society’ for society and science. EMBO Rep. 2002, 3, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasanoff, S. Ordering knowledge, ordering society. In States of Knowledge: The Co-production of Science and Social Order; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 13–45. [Google Scholar]

- Weingart, P. Scientific expertise and political accountability: Paradoxes of science in politics. Sci. Public Policy 1999, 26, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leydesdorff, L. The triple helix model and the study of knowledge based innovation systems. arXiv 2009, arXiv:09114291. [Google Scholar]

- Deakin, M.; Leydesdorff, L. The triple helix model of smart cities: A neo-evolutionary perspective. In Smart Cities; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 146–161. [Google Scholar]

- Breeman, G.; Dijkman, J.; Termeer, C. Enhancing food security through a multi-stakeholder process: The global agenda for sustainable livestock. Food Secur. 2015, 7, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowotny, H. Democratising expertise and socially robust knowledge. Sci. Public Policy 2003, 30, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edenhofer, O.; Kowarsch, M. Cartography of pathways: A new model for environmental policy assessments. Environ. Sci. Policy 2015, 51, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, M. Science’s new social contract with society. Nature 1999, 402, C81–C84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasanoff, S. A mirror for science. Public Underst. Sci. 2014, 23, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böcher, M.; Krott, M. Science Makes the World Go Round. In Successful Scientific Knowledge Transfer for the Environment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Butter, F.A.G. The Industrial Organisation of Economic Policy Preparation in the Netherlands; Vrije Universiteit: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dietz, T. Bringing values and deliberation to science communication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 14081–14087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, H. Science, Policy, and the Value-Free Ideal; University of Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, G.G. Zur Forschungsethik gehört auch eine Ethik der Politikberatung. In Makroökonomie im Dienste der Menschen—Festschrift für Gustav A; Horn:Marburg: Metropolis Verlag, Germany, 2019; pp. 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, G.G. Scientists who oversell their results are a big problem for science. Elephant in the Lab 2018. [CrossRef]

- Besley, J.C.; Tanner, A.H. What science communication scholars think about training scientists to communicate. Sci. Commun. 2011, 33, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Sluijs, J. Uncertainty as a monster in the science–policy interface: Four coping strategies. Water Sci. Technol. 2005, 52, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gigerenzer, G.; Gaissmaier, W.; Kurz-Milcke, E.; Schwartz, L.M.; Woloshin, S. Helping doctors and patients make sense of health statistics. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2007, 8, 53–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | In countries such as Canada, Germany, the US, and the UK, academies have become important actors on the science-policy interface. |

| 2 | Weinberg 1972, p. 209. |

| 3 | “Sputnik shock” refers to a period of public fear and anxiety in Western countries about the perceived technological gap between the United States and the Soviet Union that was caused by the Soviets’ launch of the world’s first artificial satellite Sputnik 1. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).