This section reports and discusses the results from the analysis of the questionnaire and interview data regarding the lecturers’ attitudes towards research and publication, and their obstacles to local and international publication.

3.1. University Lecturers’ Attitudes towards Research and Publication

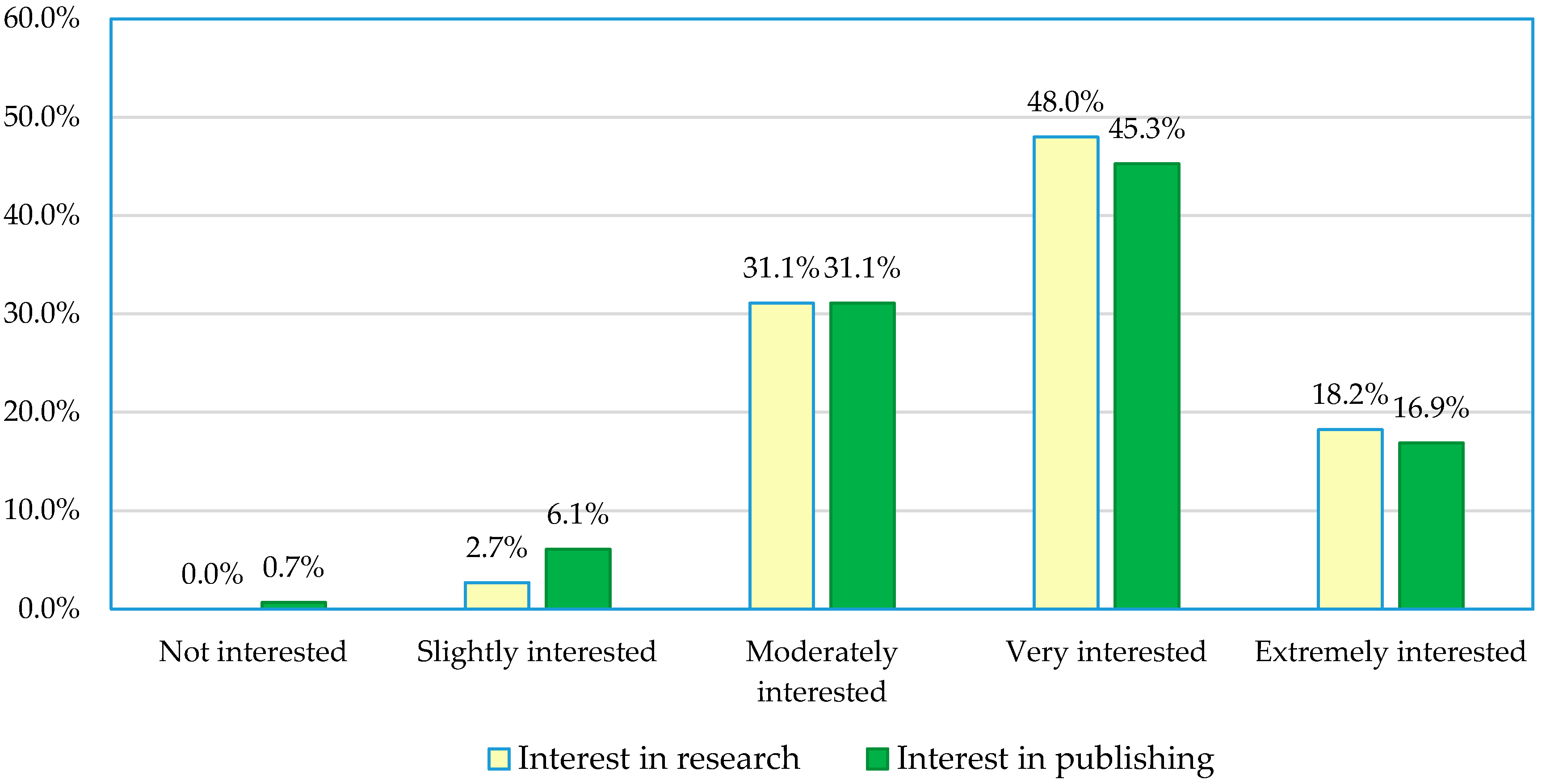

The analysis of the questionnaire data revealed that almost all of the lecturers participating in the study agreed that research is important (only 2% thought that research is slightly important) (see

Figure 2). Similarly, almost all of the participants agreed that publishing is important (except for 1.4% who thought that publishing is slightly important).

As can be seen from

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, although most participants agreed that research and publishing are important, their degrees of interest in research and publishing were not as high. 2.7% of the participants said that they were only slightly interested in research and 6.8% of the participants said that they were slightly interested or not interested in publishing at all. While around 80% of the lecturers perceived research and publishing as important or extremely important, only around 60% of the lecturers were interested or extremely interested in research and publishing. Most lecturers interviewed pointed out that research is important as they can contribute to knowledge in the field and they consider it necessary for university lecturers to do research so they can improve their own teaching and become role models for their students. Some lecturers explained that they do research because they can gain real experience and apply the research results in improving their teaching, but they do not care much about writing it up for publication as it is time-consuming.

In order to see if there were any differences in the lecturers’ attitudes towards research and publishing across faculties (disciplines), age groups, highest qualifications (BA, MA and PhD), and education (local or overseas), one-way ANOVA and independent samples t-tests were run. There were no significant differences in the means of the four variables (the importance of research and publishing and the interest in research and publishing) across 8 different faculties. Likewise, the importance of research and interest in publishing did not differ significantly across age groups, but the importance of publishing and interest in research did. Post hoc tests on these variables revealed that there was only one significant difference in the interest in research between those under 30 and those above 50 at the level of .05 (Sig. = 0.042). The mean score for lecturers under 30 years of age was only 3.5 whereas that for lecturers above 50 was 4.1. This shows that senior lecturers were significantly more interested in research than young lecturers.

While there were no statistically significant differences across education types (i.e., whether lecturers have received education overseas or not), there were significant differences across the highest qualifications held by the lecturers.

Post hoc tests revealed that university staff with a PhD degree or MA degree tended to regard research as more important than those with a BA degree. Similarly, publishing was given a higher importance by academic staff with a PhD degree than those with a BA degree (

M = 4.1 and 3.4, respectively) (see

Table 2).

Post hoc tests also showed that there were significant differences between the attitudes of PhD, MA and BA holders in terms of interest in research and publishing. Lecturers with a PhD degree were more interested in research than those with an MA degree and those with an MA degree were more interested in research and publishing than those with a BA degree.

It is interesting to see from

Table 2 that publishing was considered a little less important than research for lecturers with a PhD or MA degree. These lecturers were also a little less interested in publishing than in doing research. A general impression from the interviews was that young lecturers, who normally hold a BA or MA degree, tend to spend more time on teaching (both in and outside the university) to earn their living, whereas some senior lecturers, who normally have a higher degree, are used to doing research and see the importance of research as discussed above; some senior lecturers mentioned they do research so it can be easier for them to be promoted to associate professors or professors. Interviewees from both extensive publishing group and limited publishing group agreed that research is important, but publishing is time-consuming, yet it is not rewarding enough. Another possible explanation for the lower interest in publishing is that it is currently not made mandatory by the university administration. Although both teaching and research are stated in the job descriptions of lecturers, lecturers are normally seen as ‘not complete’ their duty if they do not teach the required number of hours in a year, but it is not the case if they do not have any publications.

Apart from age and qualifications, the amount of time spent on teaching activities also seemed to be an important factor in the lecturers’ perception of the importance of research and publishing and their interest in research and publishing.

Post-hoc tests showed that there was a significant difference between those who spent 61%–80% of their time on teaching and those who spent only 20-40% or 41-60% of their time on teaching (see

Table 3).

Table 3 shows that lecturers who had a heavy teaching load tended to have less interest in research and publishing. Or, indeed, we can say that some lecturers took up more teaching hours because they were not interested in research or publishing. Some lecturers when being interviewed even said that they see their main duty as teaching, not doing research.

In order to determine whether lecturers with different research experiences had different responses in terms of their perception of the importance of research and publishing and their interest in research and publishing, independent samples

t-tests were conducted on the variables. The means of the variables are shown in

Table 4.

The independent samples

t-tests showed that all the differences between the mean scores (for “No” and “Yes” answers, see

Table 4) were statistically significant. From

Table 4, we can easily see that lecturers who have participated in research projects or have been a research project leader tended to consider research and publishing more important and are more interested in research and publishing than those who have not. We can say that lecturers tend to develop their interest in research and publishing when they get involved in these activities. It may also be true that they participate in research projects as they see the importance of research and publishing.

Similarly, one-way ANOVA conducted on the respondents’ publication experience and their perceptions also yielded greatly significant results. The mean scores are shown in

Table 5.

As can be seen in

Table 5, the mean scores for lecturers who have published internationally were much higher than those who have only published locally, which, in turn, were considerably higher than the mean scores for those who have not published at all. It seems that the more experience lecturers have with publishing, the greater importance and interest they put on research and publishing. Actually, many interviewees mentioned that young lecturers should be exposed to research and publications before they can develop their own interest in them. Many suggested that more experienced researchers should try to involve novice researchers in their projects and guide them through the process of research and publication so they can get used to the process and learn how to do it themselves. Once they have had some experience, they would no longer view research and publishing as mythical or unachievable.

3.2. Obstacles to Local and International Publication

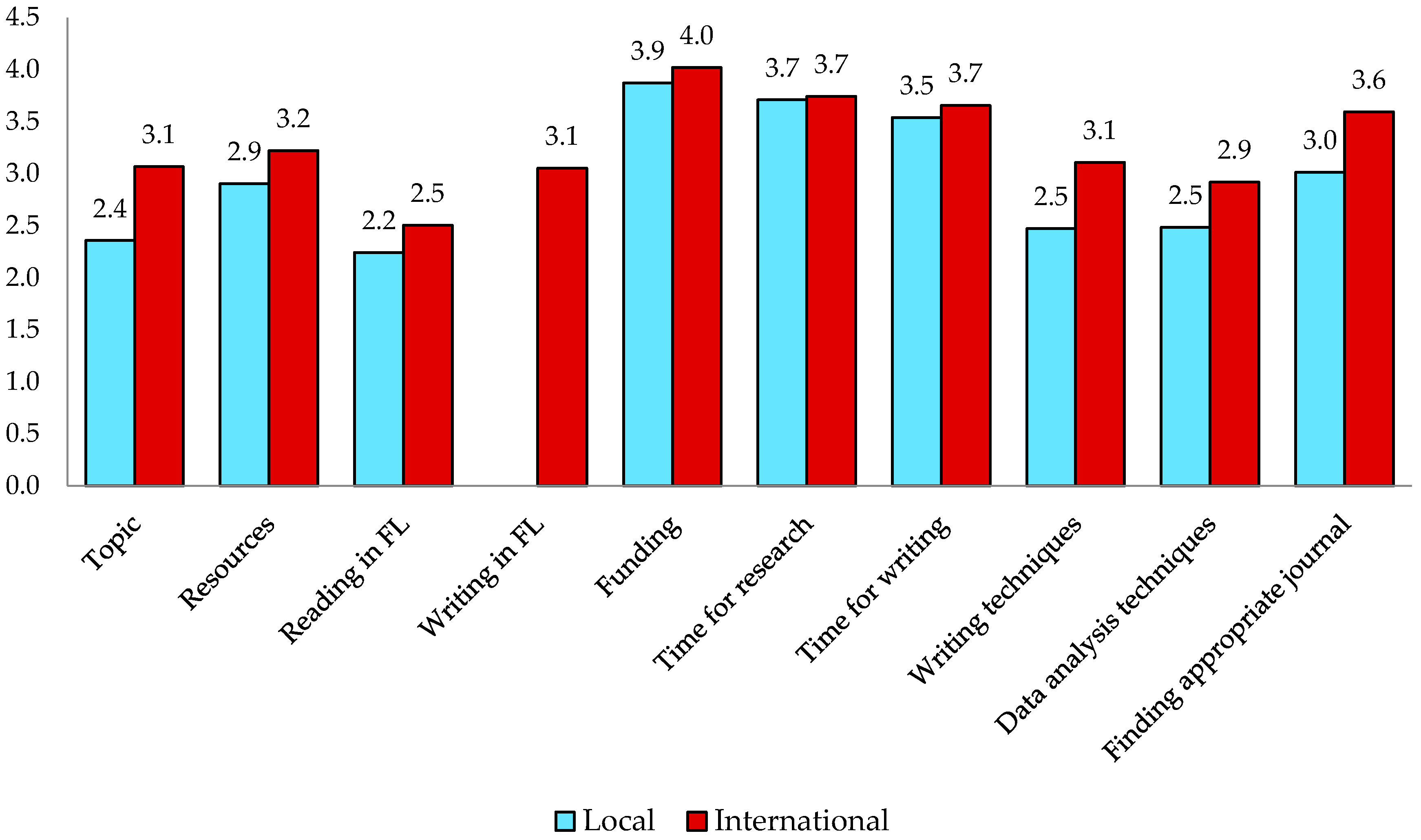

The survey results of 148 lecturers show that they have difficulties with all the factors asked in the questionnaire: difficulty with finding a good topic, difficulty with finding resources/accessing databases, difficulty in reading materials written in a foreign language (FL), difficulty in writing in a foreign language (for international publication), lack of funding, lack of time for doing research, lack of time for writing for publication, lack of research paper writing skills and data analysis skills, and difficulty in finding appropriate journals for their paper (see

Figure 4). Among these obstacles, three obstacles (with

M ≥ 3.5) stand out for both local and international publication (i.e., funding, time for research and time for writing) and one extra for international publication (i.e., finding appropriate journals).

The specific percentages of participants for different levels of difficulty in the above mentioned areas can be found in

Table 6.

3.2.1. Topic

As can be seen from

Figure 4 and

Table 6, finding an appropriate topic does not seem to be an obstacle for local publication (

M = 2.4), but it is a moderate obstacle for international publication (

M = 3.1). Only 8.1% of the lecturers considered topic a serious or very serious obstacle to local publication, whereas the corresponding percentage for international publication was 37.9%. Most interviewees admitted that finding a good topic for international publication is much more difficult than finding one for local publication as the required standard is higher; and to be published internationally, researchers have to read extensively, especially international literature, to be able to form a worthy topic for research. This finding is in line with Omer’s [

14], who found that “originality of high intellectual topics” was among the greatest barrier to faculty members at Najran University in publishing in international ISI journals (p. 87).

One-way ANOVA result showed that there were statistically significant differences among lecturers in different faculties in relation to their difficulty in finding appropriate topics for local publication (p = 0.001). Post-hoc Tukey tests revealed statistically significant difference between lecturers from the Faculty of Literature and Linguistics (M = 1.6) and those from the Faculty of Oriental Studies (M = 2.5), Faculty of International Relations (M = 2.8), and Faculty of English Linguistics and Literature (M = 2.7). This can be explained by the fact that even when researchers in the areas of English Linguistics and Literature, International Relations or Oriental Studies would like to form a topic for local publication, they would have to situate their research in international literature, which lecturers from the Faculty of Literature and Linguistics do not have to do. Interestingly, a similar ANOVA conducted for international publication showed that there were no statistically significant differences among the faculties. Lecturers from all faculties found it moderately difficult to find a topic for research papers to be published internationally.

One-way ANOVA conducted on age as a factor also yielded significant differences between different age groups in viewing topic as an obstacle to both local publication and international publication. Post-hoc tests showed that there was a significant difference between those under 30 (M = 2.8) and those above 40. It seems that senior lecturers had less difficulty in finding appropriate topics for publication thanks to their experience with the field. They tend to read more and are easier to identify new research trends in the area than younger lecturers.

While there were no statistically significant differences between lecturers who have been educated overseas and those who have not, ANOVA and Welch test results showed that lecturers with a PhD degree had less difficulty in finding appropriate topics for both local and international publication than BA and MA holders. This is perhaps due to the fact that PhD holders are more likely to be senior lecturers, and as discussed above, senior lecturers had less difficulty in finding topics than younger lecturers. It might also be the case that those with a PhD degree have undergone some training in being original and in situating their research within the existing literature.

Independent samples t-tests were also conducted to examine if there were significant differences in relation to publication experience and research experience. The results showed that publication and research experience did make significant differences for local publication (p = 0.000). This is not surprising as the more practice lecturers have with research and publication, the easier it is for them to think of an appropriate topic.

3.2.2. Resources

Finding information resources seems to be a bigger obstacle than finding appropriate topics to both local and international publication. As can be seen from

Table 6, 31% of the lecturers surveyed considered this a serious or very serious obstacle for local publication and 45.3% for international publication. A large number of interviewees across faculties also suggested that the university library should provide more scholarly journals and databases for lecturers. Although the central library of Vietnam National University of Ho Chi Minh City has made effort in providing lecturers with access to international databases such as Science Direct or ProQuest, the accessibility is very limited. Lecturers can only access the abstracts, and if they find the article relevant, they have to send requests to the library so they can download and send the articles to the individual lecturer. This process can take several days and it can demotivate the researcher.

Similar to topics, one-way ANOVA results showed that while there was no statistically significant difference across faculties in relation to finding resources as an obstacle to international publication, there were significant differences across faculties for local publication (p = 0.001). Post-hoc tests revealed that lecturers from the Faculty of International Relations and the Faculty of English Linguistics and Literature (M = 3.3 and 3.5, respectively) encountered much more difficulties in finding information resources than those from the Faculty of Literature and Linguistics (M = 1.9). This is possibly due to the fact that even in writing for local publication, lecturers from the Faculty of English Linguistics and Literature or the Faculty of International Relations often have to read and review materials written in English, which are more difficult to access than materials published in Vietnamese.

As with faculties, one-way ANOVAs with age did not yield any statistically significant differences across age groups for international publication, but there were significant differences for local publication (

p = 0.001).

Post-hoc tests showed that there was a significant difference between those under 30 (

M = 3.5) and those above 50 (

M = 2.5) in terms of how difficult it was for lecturers to find information resources. This finding seems to contradict with Alzahrani’s [

13] finding that academic staff in Saudi universities who have more than five years of experience have greater difficulty with accessing articles. While there were no significant differences in terms of whether the lecturers have been educated overseas or not, there were significant differences across qualifications for both local and international publication (

p = 0.000 and 0.007, respectively). Academic staff with a PhD degree did not seem to have as much difficulty in accessing materials as those with an MA or BA degree. One possible explanation for this is that PhD holders, who are likely to be senior lecturers, have had more experience with the literature and thus have more experience in searching for the information that they need.

3.2.3. Reading in a Foreign Language

Reading in a foreign language represented the least obstacle to both local and international publication (

M = 2.2 and 2.5, respectively, as shown in

Figure 4). This is not surprising for local publication as researchers might not need to read materials written in a foreign language at all. In fact, one can hardly find English materials in the reference list at the end of research papers published in Vietnamese journals. However, this result may be due to the respondents’ good reading ability. An analysis of the responses to question 8 of the questionnaire reveals that 83.8% of the respondents considered their foreign language reading ability good or very good.

Robust tests of equality of means (Welch and Brown-Forsythe) results showed that there were significant differences across faculties in relation to reading in a foreign language for both local and international publication (p = 0.000). Post-hoc tests indicated that lecturers from the Faculty of English Linguistics and Literature had significantly less difficulty in this aspect than those from the Faculties of Social Work, Geography and Anthropology for local publication (M = 1.4 vs. M = 2.7, 2.9, 3.1, respectively). The differences were even greater for international publication. The mean for the Faculty of English Linguistics and Literature was only 1.4, whereas the means for the Faculties of Social Work, Geography, Anthropology, Oriental Studies and Vietnamese Studies were 3.3, 3.1, 3.4, 2.6 and 2.6, respectively. Such results are not surprising, as lecturers from the English Faculty of course have advantage in English reading ability over those from other faculties. One interviewee from the Faculty of Social Work and one from the Faculty of Oriental Studies commented that their English reading ability is very limited, and yet information resources in Vietnamese (i.e., books or journal articles) in their disciplines are rare. They even suggested that lecturers who have studied abroad should volunteer to translate English books into Vietnamese so that young lecturers in the faculty can access those materials. This suggestion, however, may not be feasible due to the vast amount of information to be translated. What would be more feasible would be to help lecturers improve their foreign language proficiency.

While lecturers in different age groups and with different publication and research experience did not differ in terms of difficulty with reading in a foreign language, lecturers with different qualifications and educational backgrounds did, and this is true for both local and international publication (p = 0.047 and 0.013 for qualification and p = 0.000 for education). It is not surprising that lecturers who have studied overseas or have obtained a PhD degree had significantly less difficulty with reading in a foreign language than those who have only studied locally or held a lower degree. Such lecturers normally have a higher language proficiency level since foreign language is an important requirement to gain scholarships to study abroad. A certain level of foreign language proficiency is also required for PhD students, even when they study in Vietnam.

3.2.4. Writing in a Foreign Language

The investigation of writing in a foreign language as an obstacle was only for international publication (i.e., through question 16 of the questionnaire only, see

Appendix A). As shown in

Table 6, 41.2% of the respondents agreed that this is a serious or very serious obstacle.

While one-way ANOVA results yielded no significant differences across age groups and qualifications, there were significant differences across faculties in relation to difficulty in writing in a foreign language. The lecturers from the Faculty of Social Work had significantly more difficulty in writing in a foreign language for international publication than those from the Faculty of Oriental Studies (

M = 3.9 and 2.8, respectively). This can be explained by the fact that most lecturers from the Faculty of Oriental Studies are proficient in the language they are teaching (such as English, Chinese or Arabic), which is also the language for their research and international publication. There were also significant differences between the English Faculty (

M = 1.6) and all the other faculties (with the means ranging from 2.8 for the Faculty of Oriental Studies to as high as 4.1 for the Faculty of Anthropology). Interestingly, in-depth interview data revealed that even senior lecturers with extensive publication admitted that they often find it hard to express their ideas in English and to write in an appropriate style. Many lecturers in the interviews expressed their reluctance to write in English. Some even admitted that sometimes they had to write their paper in Vietnamese and then had it translated into English. Such a practice has also been identified in studies of Spanish scholars by Burgess et al. [

17] and Pérez-Llantada et al. [

29].

Independent samples

t-tests also showed that there were significant differences between those who have been educated overseas and those who have not (

M = 2.5 vs. 3.3, respectively). While there were no significant differences across publication experiences and research project participation experiences, experience of being a research project leader did make a difference (with

p = 0.032). The interview data revealed that when lecturers only participated in a research project led by other researchers instead of leading a project themselves, most of the time they did not have to write up the paper. They only collected and/or analyzed the data and left the writing to the foreign partner. They would be happy to be included in the paper as second author; some of them did not even have their name included in the paper as they did not participate in the writing. This explains why some lecturers have participated in international research projects, but they did not have any international publications out of the projects. Such disadvantage reflects what Flowerdew [

30] called the ‘marginalized status’ of scholars who use English as an Additional Language (p. 84).

3.2.5. Funding

As can be seen in

Figure 4, funding posed the biggest obstacle to both local and international publication (

M = 3.9 for the former and 4.0 for the latter). 72.3% of the lecturers found lack of funding a serious or very serious obstacle to local publication and an even greater percentage (75%) for international publication. This finding is very different from the finding of Tahir & Bakar [

12], who found that poor funding resources was not the major barrier to the Malaysian scholars in their study. This might be explained by the better funding support and distribution in Malaysia compared to Vietnam.

Results of one-way ANOVA and independent samples t-tests showed that there were no significant differences across age groups, qualifications, places of education, publication and research experience for both local and international publication. Therefore, we can conclude that this obstacle is very common across different categories of lecturers. The only variable that caused significant differences was faculty or discipline (p = 0.003 and 0.000 for local publication and international publication, respectively). The lecturers from the Faculty of Geography found funding a significantly greater obstacle to local publication than those from the Faculty of Oriental Studies or the Faculty of Literature and Linguistics (M = 4.6, 3.4, 3.4, respectively). As for international publication, the lecturers from the Faculty of Literature and Linguistics considered funding significantly less an obstacle (M = 3.5) than those from the Faculty of Geography (M = 4.3), Social Work (M = 4.4), and Anthropology (M = 4.5).

According to the interviewees from the Faculties of Geography, Social Work and Anthropology, funding is crucial in conducting research in their disciplines as their studies mostly involve field trips; without financial support from the university or other organizations it would be impossible for them to have good research for international publication. In contrast, studies conducted by researchers in the discipline of Vietnamese Literature or Linguistics mainly involve library research or text analysis. Their need for funding is therefore not as great as those from other faculties or disciplines. Also from the interviews, some lecturers suggest that funding is not only needed for conducting research, but also for attending national or international conferences and for editing assistance. As one interviewee from the Faculty of International Relations rightly stated, “If the university does not provide travel grants for lecturers to attend international conferences (as is the case at the University of Social Sciences and Humanities), how can we present our research to international audience and receive valuable comments from experts in the field, so we can be more confident in revising our work and submitting to prestigious international journals?” [IR2].

As pointed out by Bauer [

26], Vietnamese government’s expenditure on research is not low; however, it has not been spent efficiently, and in many cases, the policy and practices are not “transparent” as noted by Nguyen & Klopper [

25]. One interviewee explained the reason why she did not apply for research funding as her reluctance to participate in the “beg and give” practice.

3.2.6. Time for Research and Time for Writing

Following funding as the greatest obstacle were time for research and time for writing (M = 3.7 for the former for both local and international publication; M = 3.5–3.7 for the latter for local and international publication, respectively).

Similar to funding, results of one-way ANOVA and independent samples t-tests on time for research and time for writing showed that there were no significant differences across age groups, qualifications, places of education, publication and research experience for both local and international publication, which means that they were obstacles to different groups of lecturers. The only factor that caused any significant differences in relation to time for research was faculty (p = 0.004 and 0.011 for local publication and international publication, respectively). The lecturers from the English Faculty found lack of time for research a significantly greater obstacle to local publication than those from the Faculty of Oriental Studies and the Faculty of Literature and Linguistics (M = 4.2, 3.4, 3.2, respectively). Time for research also posed a significantly greater obstacle to international publication for lecturers from the Faculty of English Linguistics and Literature (M = 4.2) than those from the Faculty of Literature and Linguistics (M = 3.3).

Time for writing also caused more an obstacle to the lecturers from the English Faculty (M = 4.2) than those from the Faculties of Social Work (M = 3.3), Geography (M = 3.3), Oriental Studies (M = 3.2), and Literature and Linguistics (M = 3.0). It seemed that lack of time for research and writing was a serious problem to the lecturers from the English Faculty. It is probably because lecturers in this faculty normally have a heavy teaching load, not just at the University of Social Sciences and Humanities, but also in other institutions and language centers. As rightly pointed out by the Dean of a faculty, apart from heavy teaching loads, senior lecturers tend to have other responsibilities such as research supervision or management, whereas young lecturers may have a lot of administrative assignments apart from teaching.

The findings in this study are in line with those in Klobas & Clyde’s [

31], Lehto et al. [

16] and Tahir & Bakar’s [

12] studies. To solve the problem of lack of time for research and writing, one interviewee suggested that the university management should be specific in assigning teaching and research duties for each lecturer. An interviewee from the Faculty of Anthropology also recommended that lecturers should be granted sabbatical leaves every now and then so they can focus on research, especially those involved in field work. Several interviewees mentioned that if their salary is high enough, they can focus more on doing research; as a result, the quality of their research would increase and they would have a better chance of being published in international journals.

3.2.7. Writing Skills and Data Analysis Skills

Research paper writing skills and data analysis skills did not seem to be an obstacle to local publication (

M = 2.5), but it was a moderate obstacle to international publication (

M = 3.1 and 2.9, respectively). As can be seen in

Table 6, 37.2% of the respondents considered writing skills a serious or very serious obstacle to international publication; the corresponding percentage for data analysis skills was 31.1%. These findings are consistent with those in Keen [

32] and Tahir & Bakar [

12]. Most interviewees said that they are afraid of writing for international publication as they are aware that international journals have higher requirements in terms of writing structure and format. Such a fear is substantiated by Chireshe et al. [

33] and Flowerdew [

34,

35], who found that poor writing style was among the most frequent reasons for editors to reject submitted papers.

One-way ANOVAs were conducted to examine if there were any significant differences across faculties for writing skills and data analysis skills. The results showed that there were no significant differences for international publication in both categories, but there were significant differences for local publication (p = 0.013 for writing skills and p = 0.026 for data analysis skills). Post-hoc tests revealed that the lecturers from the Faculty of Literature and Linguistics found writing skills significantly less an obstacle than those from the Faculty of International Relations (M = 1.3 and 3.3, respectively). The lecturers from this faculty also found less difficulty with data analysis skills than those from the Faculty of International Relations and the Faculty of English Linguistics and Literature (M = 1.8, 3.1, 2.9, respectively). This is not surprising as experts in the discipline of Literature and Linguistics are well known for their good writing skills due to the nature of the discipline. Furthermore, papers in this discipline are mainly theoretical papers and thus they may not need to conduct empirical data analysis.

Results from one-way ANOVAs also yielded significant differences across age groups and qualifications in relation to both writing skills and data analysis skills for both local and international publication, with lecturers between 41 and 50 or above 50 having significantly less problem with writing skills than those under 30 and lecturers with a PhD degree having less difficulty with writing skills than those with an MA or BA degree. This is predictable as they are supposed to have more experience with data analysis and the writing up of the study.

Independent samples t-tests showed that while place of education did not cause any significant differences in terms of writing skills or data analysis skills as obstacles for local publication, it did cause significant differences for international publication (p = 0.001 and 0.002 for writing skills and data analysis skills, respectively). Lecturers who have studied overseas had significantly less problem with writing skills than those who have not (M = 2.7 and 3.3, respectively for writing skills, and M = 2.5 and 3.1 for data analysis skills). It seems that the former have received better training on how to write or structure a research paper in a foreign language. Also, as some interviewees pointed out, their first international publication was jointly written with their PhD supervisors while they were studying overseas, from whom they received a lot of guidance for data analysis and the write-up of the paper.

As expected, the lecturers’ publication experience did play an important role in both their writing skills and data analysis skills. Results of independent samples t-tests indicated that lecturers who have published had significantly less problem with writing skills and data analysis skills (M = 2.4) than those who have not (M = 2.8). As the saying goes, “practice makes perfect”. The more they write, the better their writing skills become. One young lecturer suggested in the interview that young researchers should be involved in senior lecturers’ research projects and be shown how to do data analysis or write up different sections of a paper.

3.2.8. Finding Appropriate Journals

Though not as big an obstacle as funding, time for research or time for writing, finding appropriate journals also caused considerable difficulty to lecturers, especially in international publication. 34.5% of the respondents found it a serious or very serious problem to local publication, while the percentage for international publication was much higher (56.1%). Many interviewees said that they have very little information of international journals, where they should send their papers or the publication procedure. Indeed, selecting an appropriate journal for a paper is not an easy task; there are different things to consider such as the credibility of the journal, the aim, scope and readership of the journal, publishing frequency, speed of the publication process [

36], or the acceptance rate of the journal [

37].

Finding journals for publication was the only obstacle that did not have any significant differences across faculties. However, age and qualification did make a difference, with younger lecturers and those who hold only a BA or MA degree having significantly greater difficulty with finding appropriate journals for their publication. This may be partly due to their lack of experience. There is also a possibility that senior lecturers or lecturers with a higher degree have more advantage over young lecturers as they have more networks and are more familiar with the publishers.

Results of independent samples t-tests showed that place of education did not influence finding journals as an obstacle to local publication, but there was a significant difference (p = 0.012) between lecturers who have studied overseas (M = 3.3) and those who have not (M = 3.8) for international publication. It is likely that lecturers who have spent time overseas have established certain networks, which makes it easier for them to find an outlet for their publication.

According to the results of independent samples t-tests, lecturers’ publication experience did affect their difficulty in finding journals or publishers for both local and international publication. Lecturers who have published found it less difficult to find appropriate journals or publishers than those who have not (M = 2.9 and 3.4 for local publication, and M = 3.3 and 3.8 for international publication). Once their paper has been accepted, they will have more advantage for the second or third time.

3.2.9. Obstacles to Local vs. International Publication

In order to see if there were any significant differences between the obstacles identified for local publication and international publication, paired samples

t-tests were conducted. The results showed that there were strongly significant differences between local and international publication for all the obstacles except for time for research (no significant difference). Many interviewees mentioned that writing for international publication is more challenging as international journals have higher standards in terms of topic, data and writing style. Also, writing papers to submit to international journals requires a certain level of language proficiency from the NNES scholar, in particular good reading and writing skills. Indeed, writing in English has been found one of NNES scholars’ main obstacles to international publication as documented in Bardi [

38], Hanauer & Englander [

39] and Uzuner [

20]. As a consequence of such challenges, researchers tend to resort to local publication rather than international publication. This finding is in line with those in Flowerdew [

40], Ge [

24], Li & Flowerdew [

41], Salager-Meyer [

42], who found that scholars tend to resort to writing in their native language.

Although not asked directly whether they would prefer to publish in English or Vietnamese, interviewees who have studied overseas and have had experience with international publication seemed to prefer publishing in English as they are used to academic writing in English. One interviewee from the Faculty of English Linguistics and Literature commented that she would not attempt to write in Vietnamese as her academic Vietnamese would be “funny” and sound like English Vietnamese. On the other hand, some interviewees suggested that it would be hard for them to publish in English as their research issue is too narrow—“only local researchers would be interested”, as admitted by an interviewee from the Faculty of Literature and Linguistics. This seems to reflect the issue of “literature segmentization” (i.e., local segment vs. international segment) as recently discussed in Beigel [

43], a study of the publishing system in Argentina; in Gantman & Rodríguez [

44], a case study of Spanish-speaking countries; or in Hanafi [

45], a study of universities in the Arab world. Although the segmentation in Vietnam is probably not as intense as what Hanafi [

45] reported in his study—“knowing a foreign language becomes a source of integration globally and isolation locally” (p. 295), the situation in Vietnam is somewhat similar. It would be more beneficial to the research world if research findings are published both locally and internationally, so they can be accessed by both local and international researchers. This is also beneficial to the researchers themselves as their research can be recognized by the society as well as by the global community.